Financial Risk Management and Resilience of Small Enterprises Amid the Wartime Crisis

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review

1.1.1. Resource-Based Theories and Financial Risk

1.1.2. Adaptation and Financial Resilience Under Crisis Shocks

1.1.3. Psychological Factors and Their Relevance to Financial Outcomes

1.1.4. Wartime Context and the Need to Study Regional Financial Resilience

- -

- Lack of quantitative assessments of how wartime financial risks affect SMEs.

- -

- Insufficient analysis of digitalization’s financial impact, beyond general descriptions.

- -

- Absence of comparative regional studies that capture how varying conflict intensity shapes financial resilience.

1.2. Justification of the Goal, Objectives, and Hypotheses of the Study

- -

- To analyze the current state of small businesses in various regions of Ukraine in conditions of the military crisis;

- -

- To evaluate and quantify the impact of the main financial risks faced by enterprises (liquidity shortages, credit risk, currency fluctuations, operational losses);

- -

- To investigate adaptation strategies and resilience mechanisms applied by small businesses in conditions of limited resources;

- -

- To assess the role of digital transformation, innovation, and social responsibility in increasing the stability of enterprises;

- -

- To develop recommendations for forming a financial risk management system capable of supporting SMEs in conditions of prolonged instability.

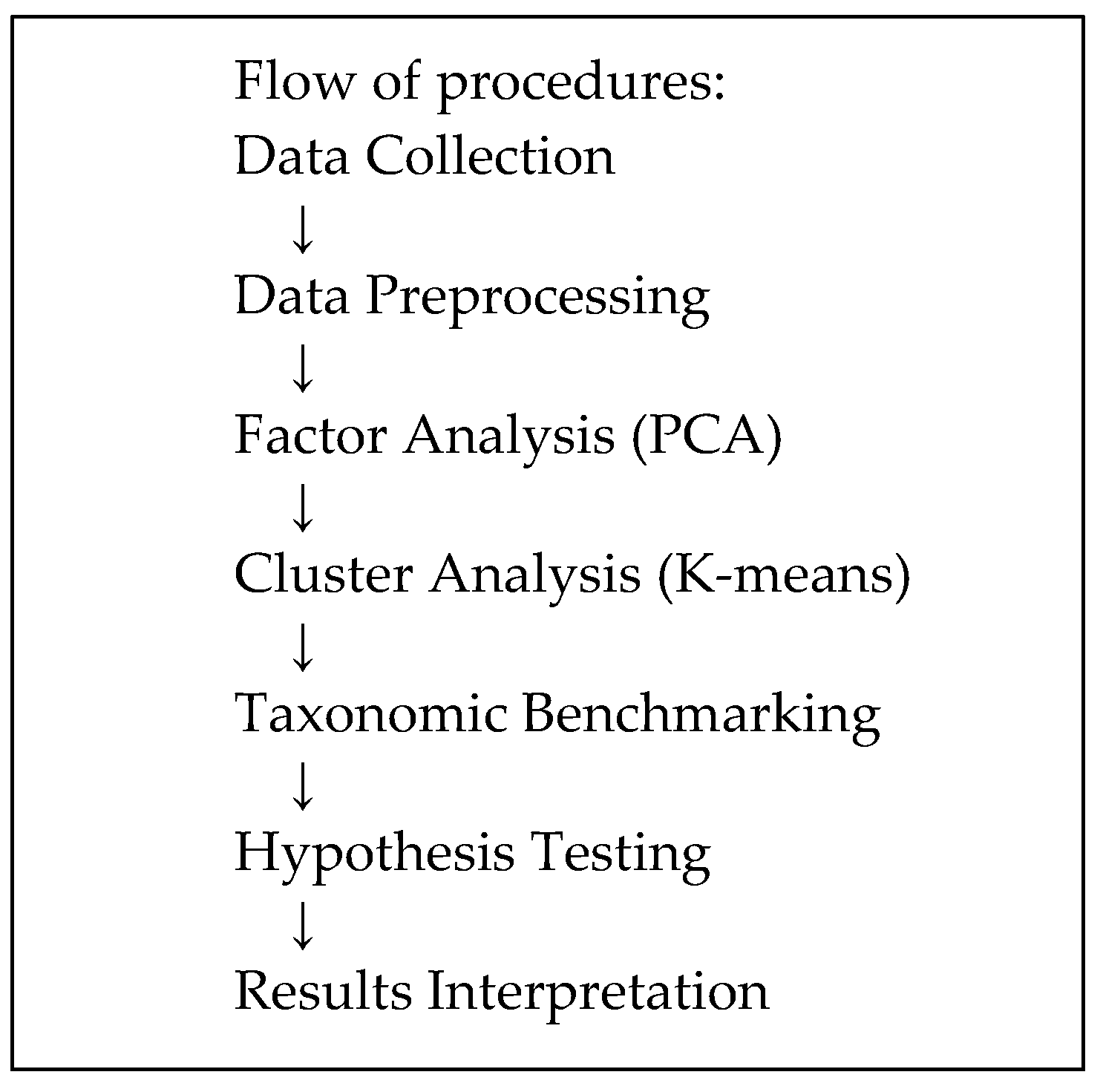

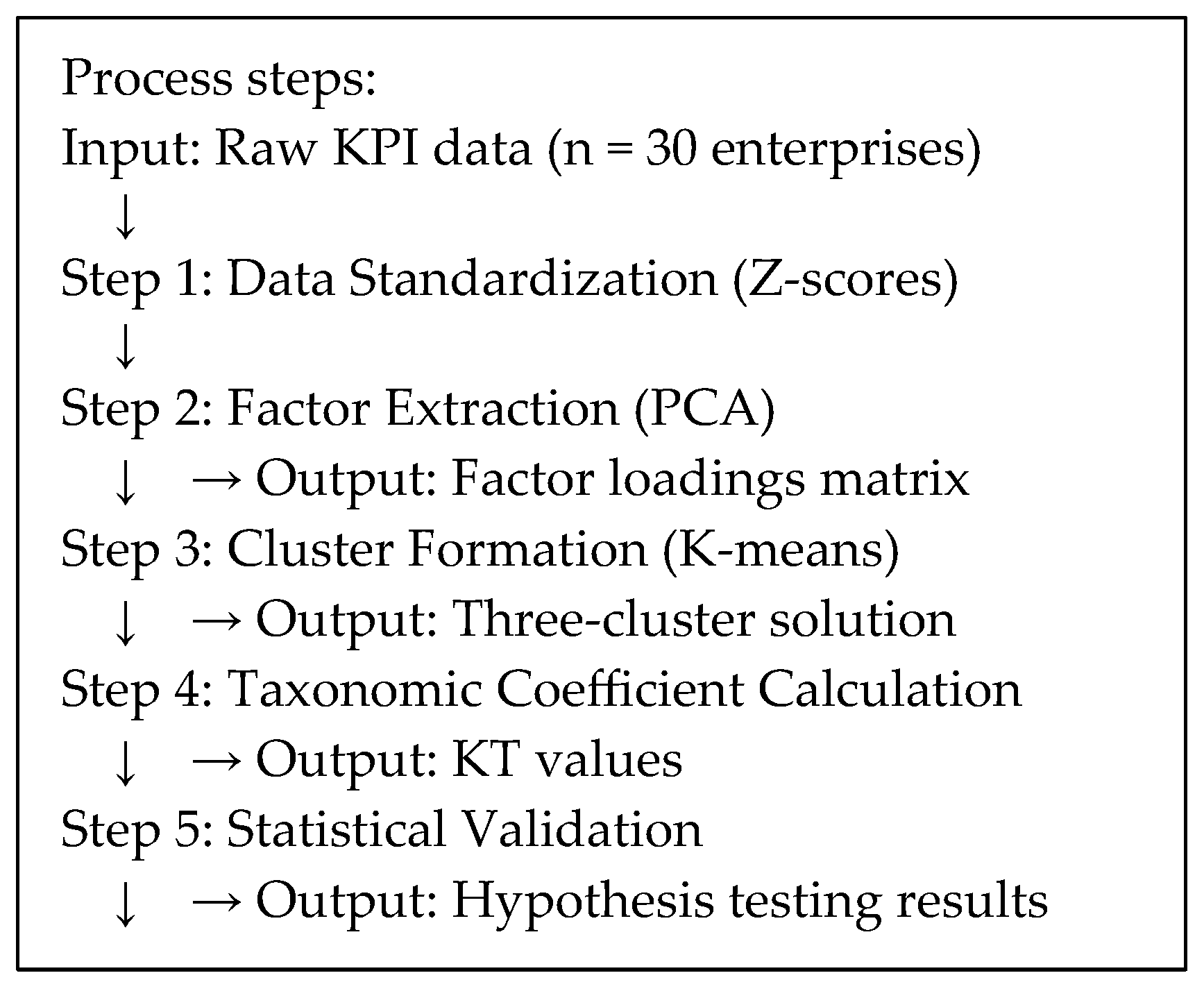

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data for Assessing the Financial Stability of Small Enterprises in Ukraine Under the Conditions of the Military Crisis

2.2. Research Methodology for Assessing Financial Resilience

- Identification of key financial determinants using exploratory factor analysis (EFA).

- Classification of SMEs into resilience profiles using cluster analysis (k-means).

- Benchmarking financial resilience through the taxonomic method to compute an integral resilience indicator (KT).

- Statistical verification of hypotheses using correlation analysis, t-tests, ANOVA, and non-parametric tests.

- Integration and validation of results through cross-validation and sensitivity analysis.

2.3. Analytical Parameters and Procedures

2.4. Statistical Assumptions, Diagnostic Checks, and Robustness Procedures

3. Results

3.1. Results of the Factor Analysis of Financial Indicators of Small Enterprise Sustainability

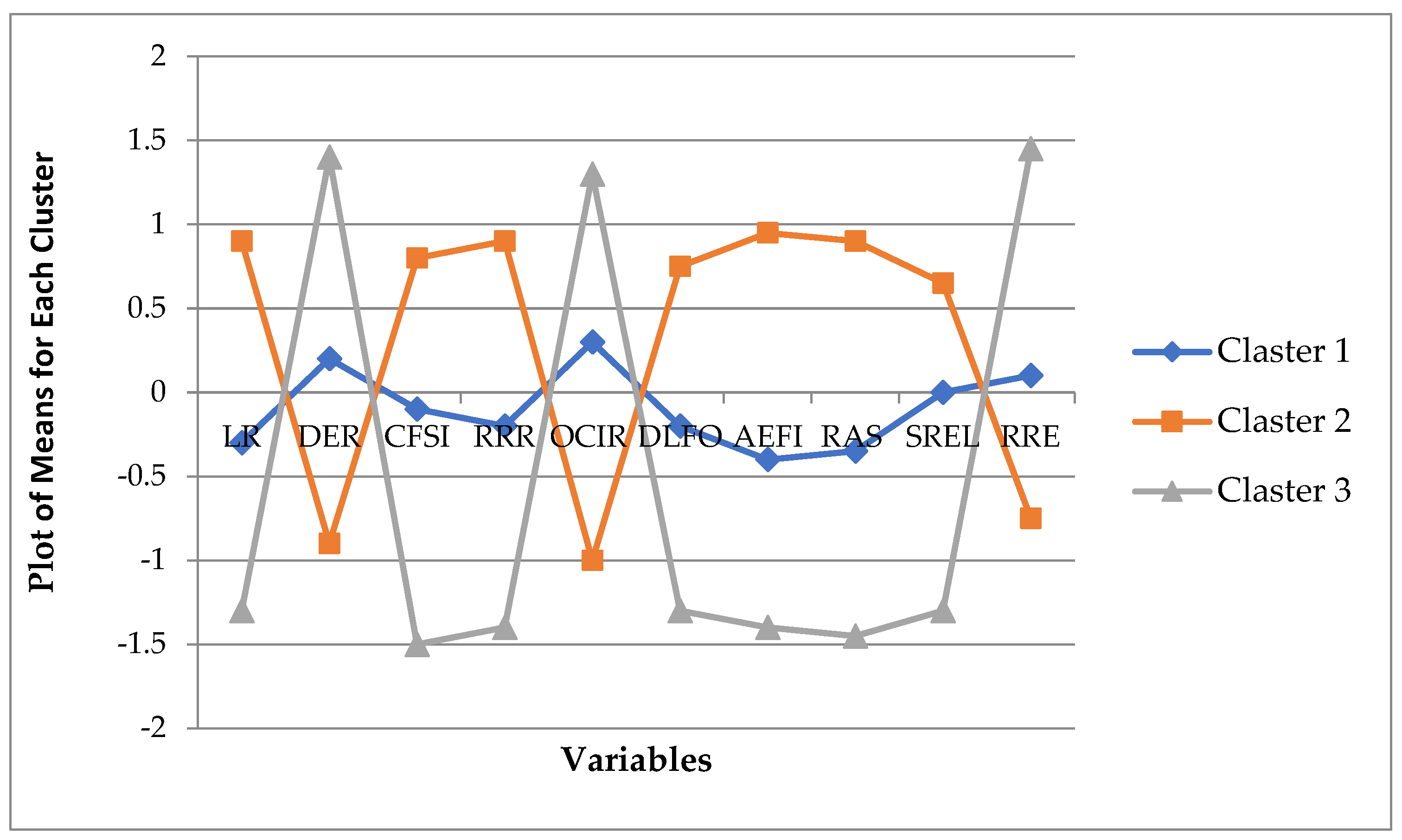

3.2. Classification of Small Enterprises by Zones of Financial Risk

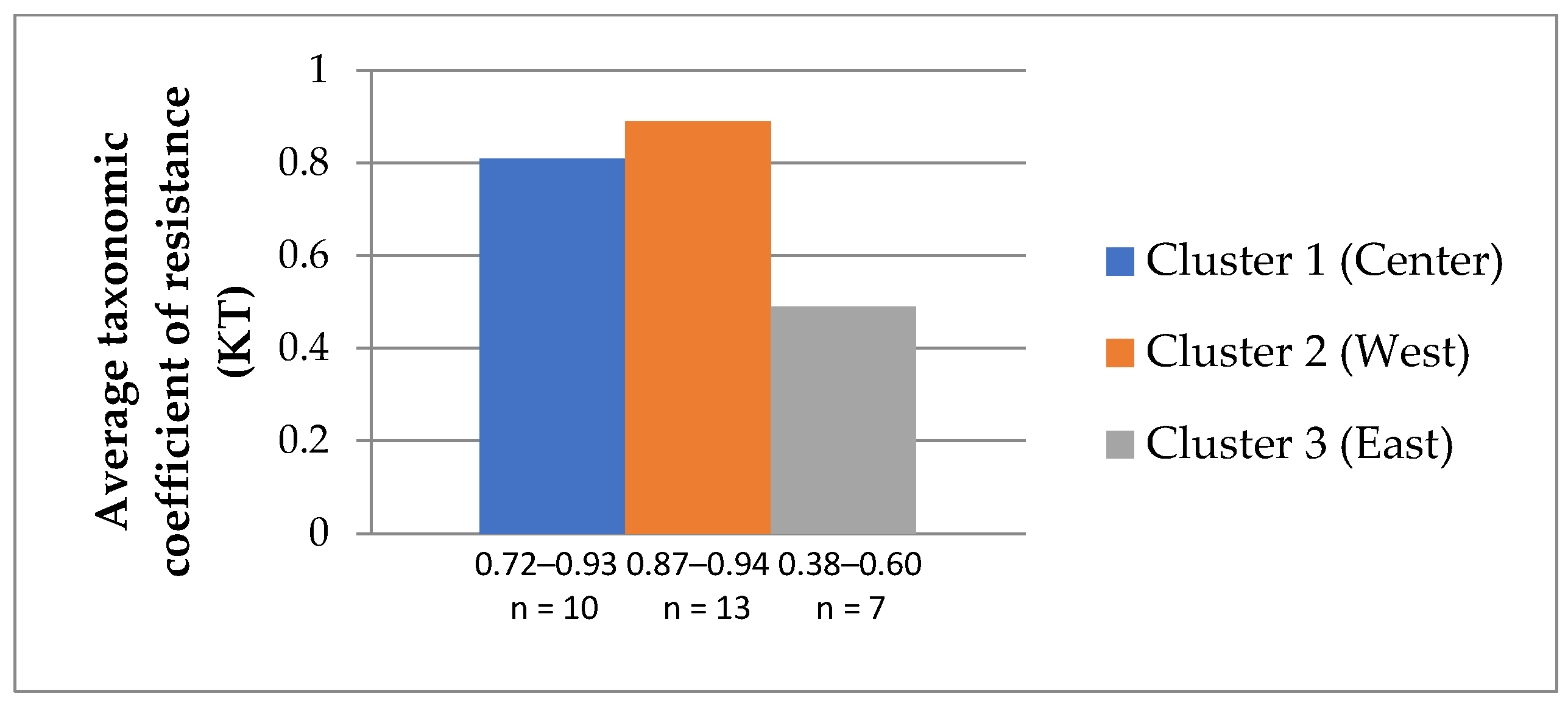

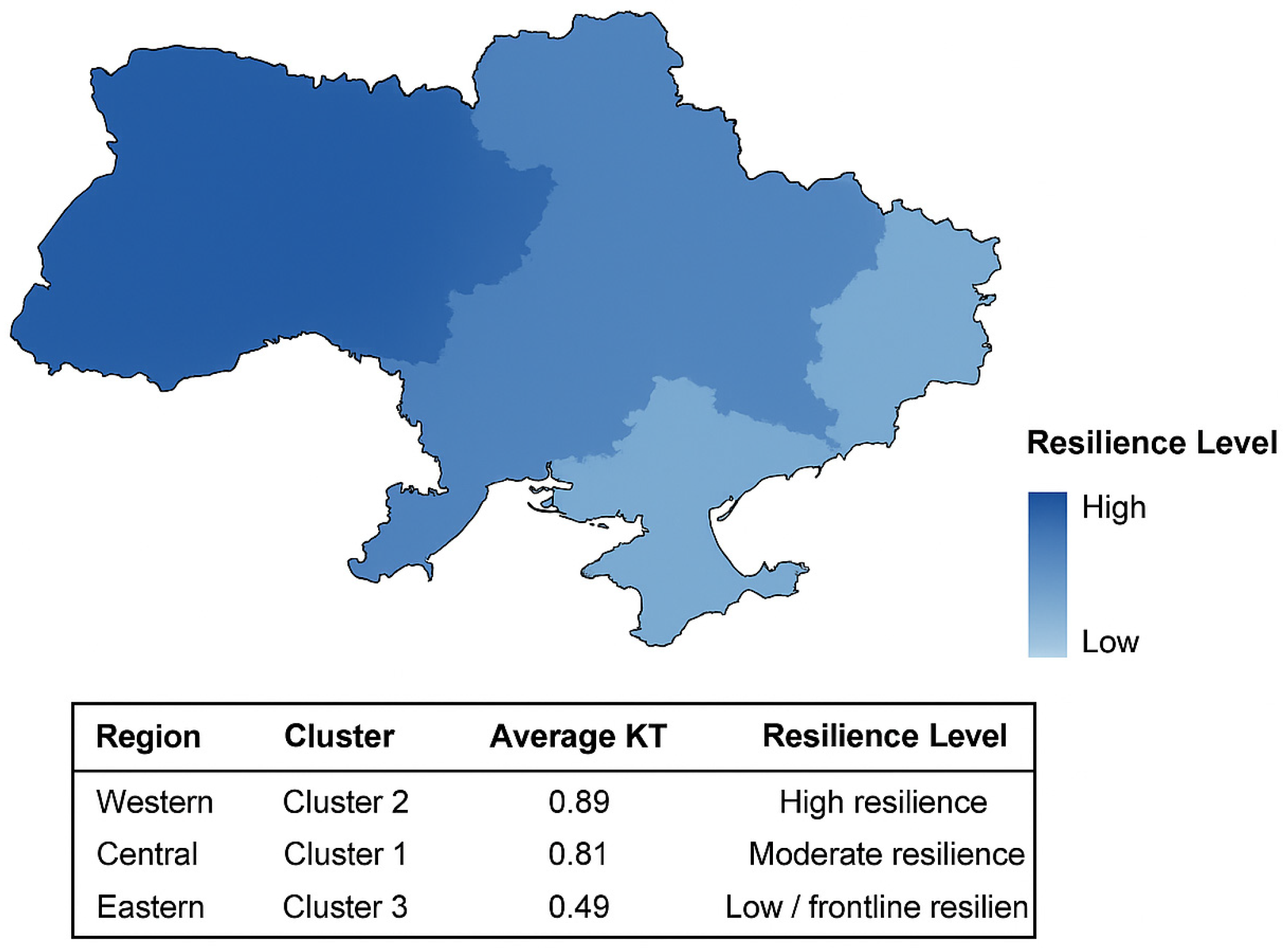

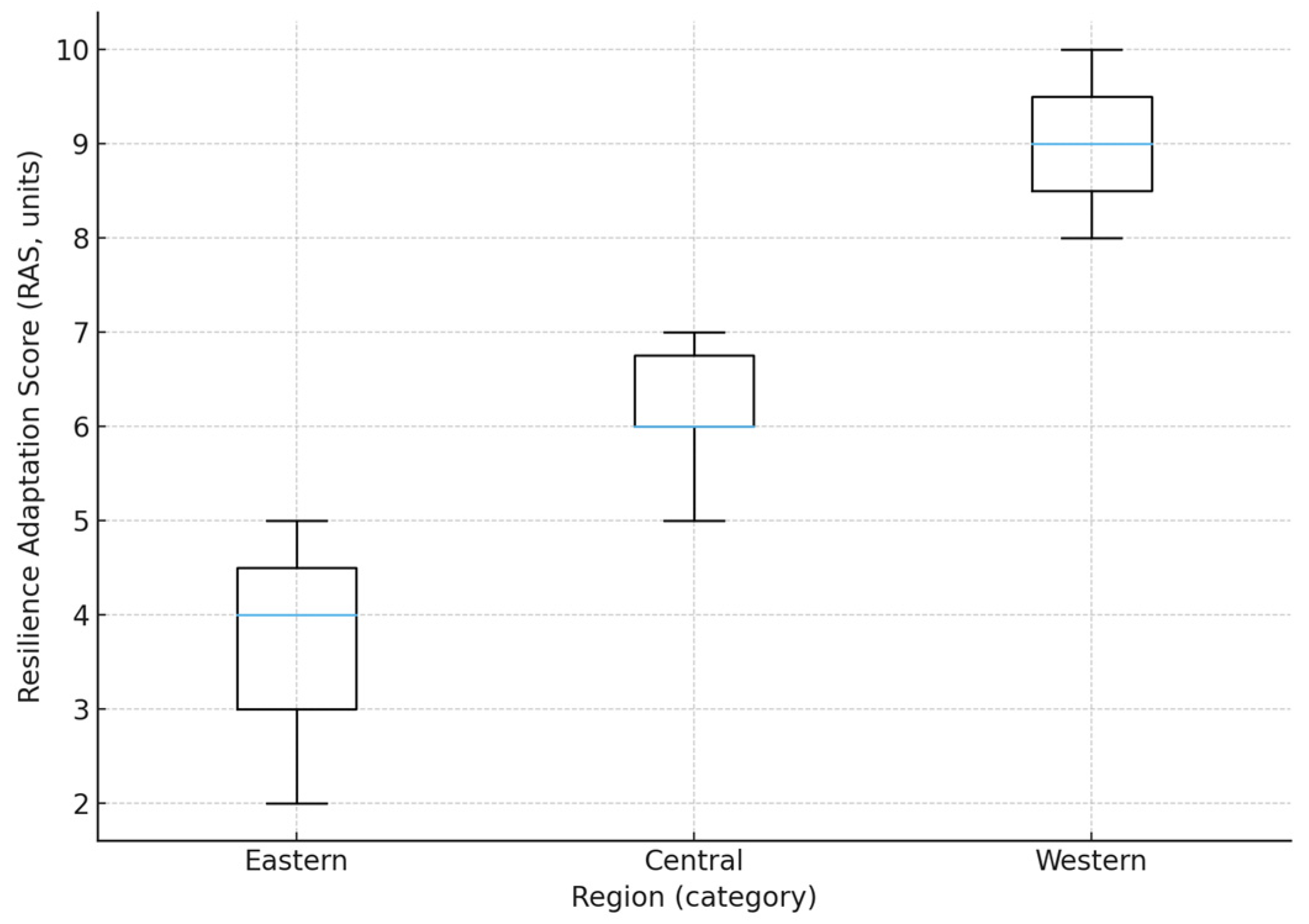

3.3. Regional Differentiation of Financial Resilience of Small Enterprises Based on the Taxonomic Method

3.4. Hypothesis Testing Using Statistical Methods

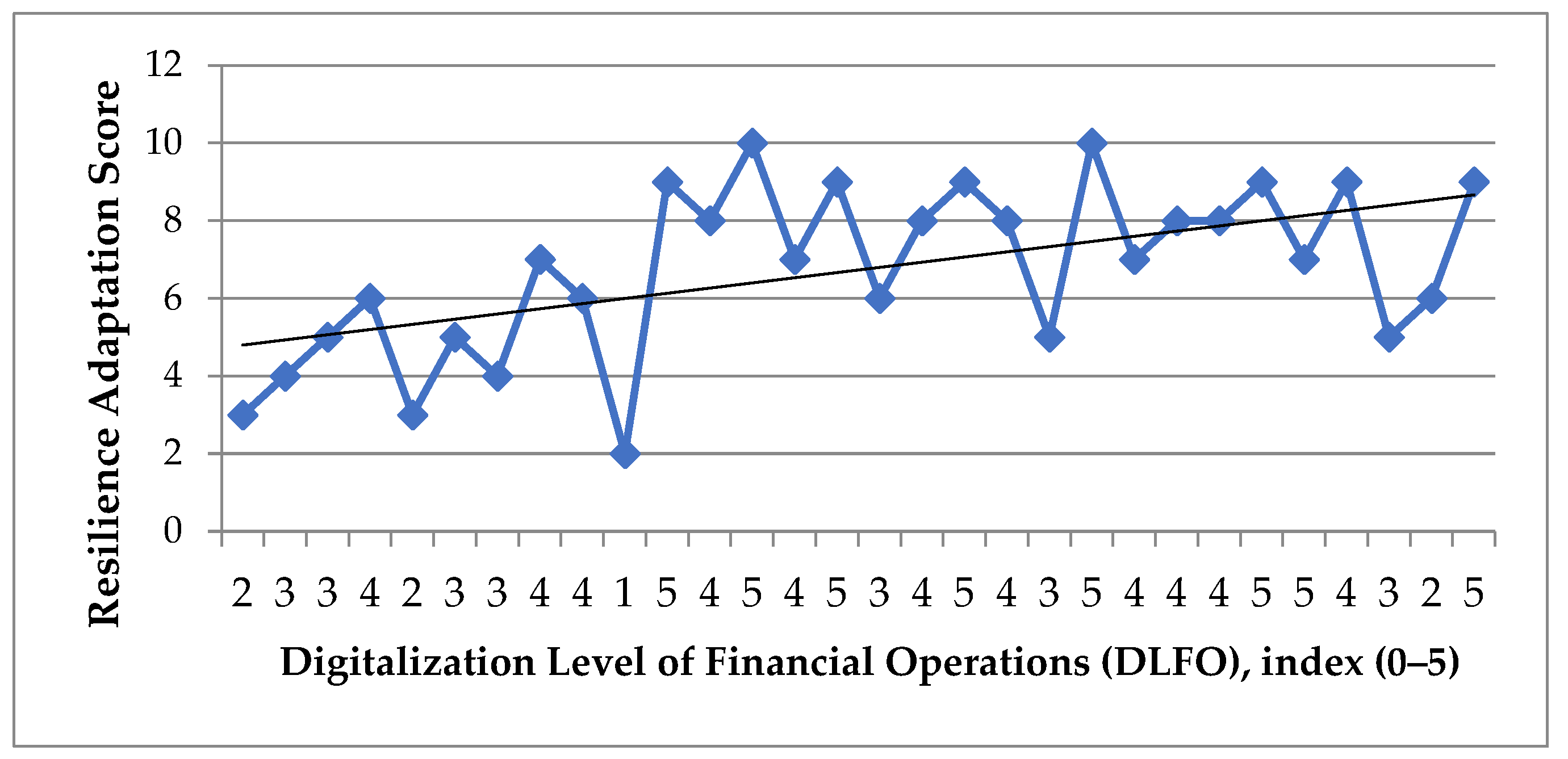

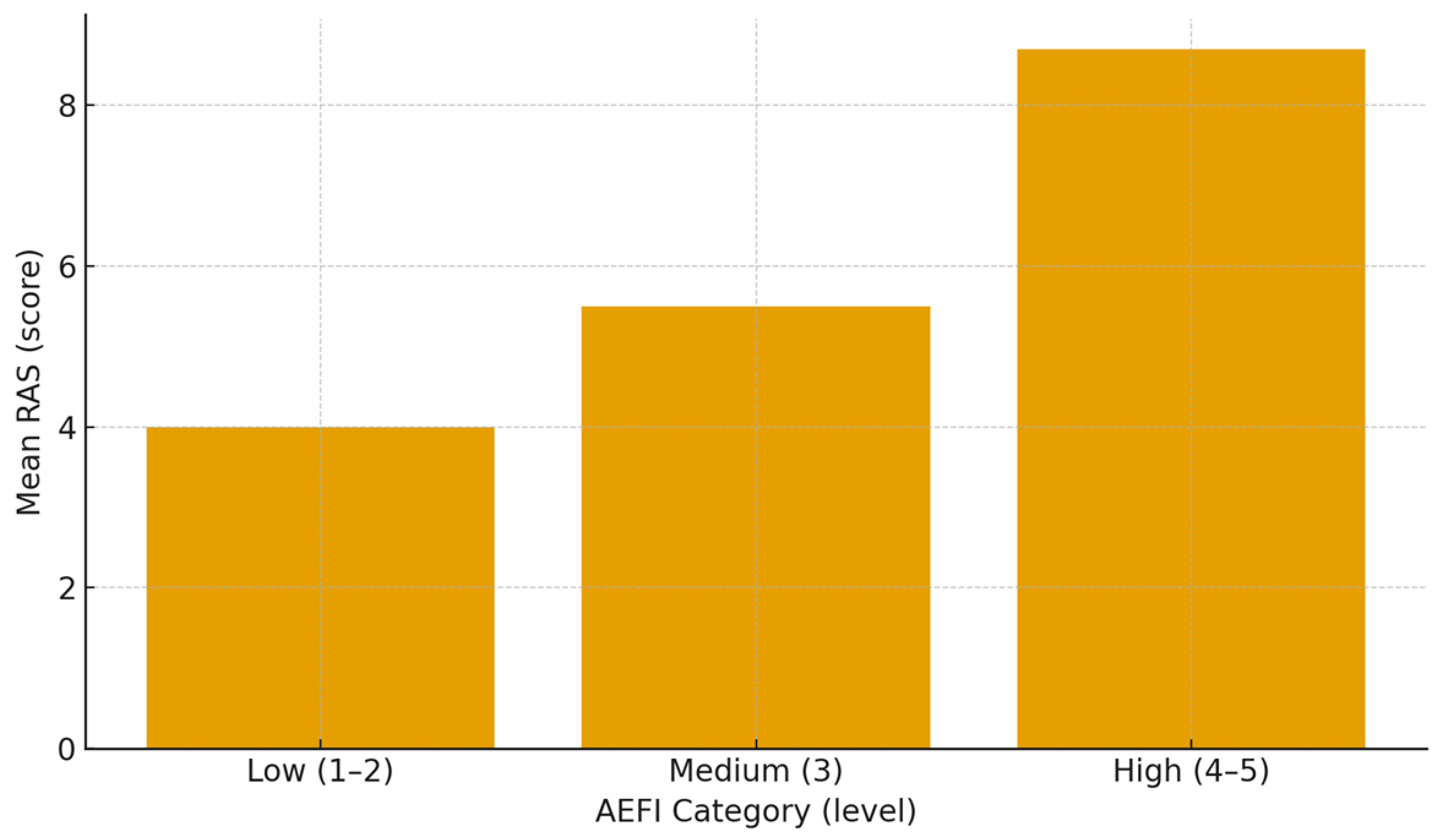

3.5. Interpretation and Visualization of Results

4. Discussion

- (1)

- Resource potential (financial, human, and organizational resources);

- (2)

- Managerial adaptability (digitalization, business model reorientation, access to external financing);

- (3)

- Social responsibility and engagement (integration into community and volunteer initiatives as a means of strengthening reputational and social capital).

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Expanding access to financial instruments for enterprises in high-risk regions;

- (2)

- Encouraging digitalization of financial operations to stabilize cash-flow management; and

- (3)

- Supporting adaptive practices that help SMEs sustain operations under prolonged instability.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Complete Dataset of Small Enterprises with Financial Indicators and Cluster Classification

| No | Enterprise | LR | DER | CFSI | RRR | OCIR | DLFO | AEFI | RAS | SREL | RRE | Cluster | Region |

| 1 | LLC “AKVA-FISH KH” | 0.8 | 2.5 | 0.3 | 45 | 85 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 9 | 3 | Eastern |

| 2 | FE “SANTONSKE” | 1.0 | 3.0 | 0.4 | 55 | 70 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 9 | 3 | Eastern |

| 3 | FE “SEMILONSKE” | 1.1 | 2.2 | 0.5 | 60 | 65 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 8 | 3 | Eastern |

| 4 | FE “FERMINSKE” | 1.3 | 1.8 | 0.6 | 70 | 60 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 8 | 1 | Central |

| 5 | LLC “Semilon-Agro” | 0.9 | 2.8 | 0.4 | 50 | 80 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 9 | 3 | Eastern |

| 6 | LLC “SANTON AGRO” | 1.2 | 2.0 | 0.5 | 65 | 75 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 8 | 3 | Eastern |

| 7 | FE “EKOFUD-SLOBODA” | 1.0 | 2.5 | 0.5 | 58 | 68 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 8 | 3 | Eastern |

| 8 | FE “POLUYIANIVSKE” | 1.4 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 75 | 55 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 4 | 7 | 1 | Central |

| 9 | FE “TORINSKE” | 1.1 | 2.1 | 0.6 | 72 | 62 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 8 | 1 | Central |

| 10 | FE “SOTON AGRO” | 0.7 | 3.2 | 0.3 | 40 | 90 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 9 | 3 | Eastern |

| 11 | LLC “PRIMUS KOR” | 1.8 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 95 | 25 | 5 | 4 | 9 | 4 | 5 | 2 | Western |

| 12 | LLC “SKYLIGHT” | 1.6 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 88 | 35 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 5 | 4 | 2 | Western |

| 13 | LLC “AGROZEMTEKHPROEKT” | 1.9 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 98 | 20 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 4 | 2 | Western |

| 14 | LLC “MK MedVyn” | 1.5 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 85 | 40 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 1 | Central |

| 15 | CEC “AMARANT AGRO ZROSHENNIA” | 2.0 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 102 | 15 | 5 | 5 | 9 | 4 | 4 | 2 | Western |

| 16 | LLC “AGRO OSTERS” | 1.4 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 78 | 50 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 5 | 1 | Central |

| 17 | LLC “NEPTUNE FISH” | 1.7 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 90 | 30 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 2 | Western |

| 18 | LLC “BT” | 1.8 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 96 | 22 | 5 | 4 | 9 | 3 | 4 | 2 | Western |

| 19 | LLC “INKVILIN” | 1.6 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 92 | 28 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 5 | 4 | 2 | Western |

| 20 | LLC “AGRO POINT GROUP” | 1.3 | 1.8 | 0.6 | 70 | 60 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 1 | Central |

| 21 | FE “ZAKHIDNE OPYLLIA” | 2.1 | 0.2 | 0.9 | 105 | 10 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 3 | 2 | Western |

| 22 | FE “SKAVA” | 1.5 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 80 | 45 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 1 | Central |

| 23 | LLC “EKO-LISBUD” | 1.7 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 92 | 32 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 3 | 2 | Western |

| 24 | FE MOHORUK K. M. | 1.6 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 87 | 38 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 3 | 4 | 2 | Western |

| 25 | LLC “ULTRA FORCE” | 1.9 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 98 | 18 | 5 | 5 | 9 | 5 | 3 | 2 | Western |

| 26 | FE “BUKOVIEN” | 1.4 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 82 | 42 | 5 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 4 | 1 | Central |

| 27 | FE “ZAPIDOK” | 1.8 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 94 | 25 | 4 | 4 | 9 | 4 | 3 | 2 | Western |

| 28 | FE “KUZHBA” | 1.2 | 1.6 | 0.6 | 65 | 55 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 1 | Central |

| 29 | FE “V FILVAROK” | 1.3 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 75 | 48 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 1 | Central |

| 30 | LLC “BEST BERRY” | 2.0 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 100 | 12 | 5 | 5 | 9 | 4 | 3 | 2 | Western |

Appendix B. Financial and Operational Indicators of Small Agricultural Enterprises in Ukraine 2024

| No. | Enterprise | LR | DER | CFSI | RRR | OCIR | DLFO | AEFI | RAS | SREL | RRE |

| 1 | LLC “AKVA-FISH KH” | 0.8 | 2.5 | 0.3 | 45 | 85 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 9 |

| 2 | FE “SANTONSKE” | 1.0 | 3.0 | 0.4 | 55 | 70 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 9 |

| 3 | FE “SEMILONSKE” | 1.1 | 2.2 | 0.5 | 60 | 65 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 8 |

| 4 | FE “FERMINSKE” | 1.3 | 1.8 | 0.6 | 70 | 60 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 8 |

| 5 | LLC “Semilon-Agro” | 0.9 | 2.8 | 0.4 | 50 | 80 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 9 |

| 6 | LLC “SANTON AGRO” | 1.2 | 2.0 | 0.5 | 65 | 75 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 8 |

| 7 | FE “EKOFUD-SLOBODA” | 1.0 | 2.5 | 0.5 | 58 | 68 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 8 |

| 8 | FE “POLUYIANIVSKE” | 1.4 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 75 | 55 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 4 | 7 |

| 9 | FE “TORINSKE” | 1.1 | 2.1 | 0.6 | 72 | 62 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 8 |

| 10 | FE “SOTON AGRO” | 0.7 | 3.2 | 0.3 | 40 | 90 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 9 |

| 11 | LLC “PRIMUS KOR” | 1.8 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 95 | 25 | 5 | 4 | 9 | 4 | 5 |

| 12 | LLC “SKYLIGHT” | 1.6 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 88 | 35 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 5 | 4 |

| 13 | LLC “AGROZEMTEKHPROEKT” | 1.9 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 98 | 20 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 4 |

| 14 | LLC “MK MedVyn” | 1.5 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 85 | 40 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 5 |

| 15 | CEC “AMARANT AGRO ZROSHENNIA” | 2.0 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 102 | 15 | 5 | 5 | 9 | 4 | 4 |

| 16 | LLC “AGRO OSTERS” | 1.4 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 78 | 50 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 5 |

| 17 | LLC “NEPTUNE FISH” | 1.7 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 90 | 30 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 5 |

| 18 | LLC “BT” | 1.8 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 96 | 22 | 5 | 4 | 9 | 3 | 4 |

| 19 | LLC “INKVILIN” | 1.6 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 92 | 28 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 5 | 4 |

| 20 | LLC “AGRO POINT GROUP” | 1.3 | 1.8 | 0.6 | 70 | 60 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 6 |

| 21 | FE “ZAKHIDNE OPYLLIA” | 2.1 | 0.2 | 0.9 | 105 | 10 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 3 |

| 22 | FE “SKAVA” | 1.5 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 80 | 45 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 4 | 4 |

| 23 | LLC “EKO-LISBUD” | 1.7 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 92 | 32 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 3 |

| 24 | FE MOHORUK K. M. | 1.6 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 87 | 38 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 3 | 4 |

| 25 | LLC “ULTRA FORCE” | 1.9 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 98 | 18 | 5 | 5 | 9 | 5 | 3 |

| 26 | FE “BUKOVIEN” | 1.4 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 82 | 42 | 5 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 4 |

| 27 | FE “ZAPIDOK” | 1.8 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 94 | 25 | 4 | 4 | 9 | 4 | 3 |

| 28 | FE “KUZHBA” | 1.2 | 1.6 | 0.6 | 65 | 55 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 5 |

| 29 | FE “V FILVAROK” | 1.3 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 75 | 48 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 4 |

| 30 | LLC “BEST BERRY” | 2.0 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 100 | 12 | 5 | 5 | 9 | 4 | 3 |

Appendix C. Formulas and Interpretation for Factor Analysis in Assessing Financial Resilience of Small Enterprises

| Step | Formula | Interpretation | |

| 1.1. Factor loading coefficient | (A1) | Values > 0.4 indicate a strong relationship between the indicator and the factor; 0.3–0.4 indicate a moderate relationship; <0.3 indicates a weak relationship. | |

| 1.2. Explained variance (R2) | (A2) | Values > 0.5 indicate that the factor explains the variability of the indicator well. | |

| 1.3. Contribution of the variable to the overall factor | (A3) | Variables with a contribution of >0.5 are retained for subsequent stability analysis. | |

| Explanation of the notations in Appendix C: Xi—value of the i-th original indicator (e.g., LR, DER, RRR, DLFO, etc.); Fk—value of the k-th factor obtained as a result of factor analysis; —covariance between the indicator Xi and the factor Fk; —variance of the indicator Xi; —variance of the factor Fk; F—factor loading coefficient, showing the strength of the relationship between the variable and the factor; R2—determination coefficient, reflecting the proportion of the variation in the variable Xi explained by the factor Fk; Total Variance—total variance explained by all factors in the model; Communality—total proportion of the variable’s variance explained by all extracted factors; Contribution—contribution of each variable to the overall factor; a higher value indicates a greater importance of the variable in interpreting the factors. | |||

Appendix D. Formulas and Interpretation for Cluster Analysis in Classifying Small Enterprises by Financial Risk Zones

| Step | Formula | Interpretation | |

| 2.1. Distributing objects into clusters | , Xi—i-th object (enterprise); Ck—k-th cluster; d(Xi, Mk)—Euclidean distance between object Xi and the center of cluster Mk. | (A4) | At each iteration, enterprise Xi is assigned to the closest cluster Ck. |

| 2.2. Recalculating cluster centers | (A5) | S_k | |

| 2.3. Completing iterations | - | The algorithm repeats steps 2.1–2.2 until the change in the position of cluster centers between iterations becomes insignificant (or the maximum number of iterations is reached). | |

Appendix E. Formulas and Interpretation for the Taxonomic Method of Benchmarking Financial Resilience of Small Enterprises

| Step | Formula | Interpretation | |

| 3.1. Data standardization | (A6) | Ensures comparability of indicators across different scales. | |

| 3.2. Construction of a reference matrix | (A7) | Each indicator is assigned the best value in the column. | |

| 3.3. Multivariate Euclidean Distance | (A8) | The smaller the distance to the benchmark, the higher the enterprise’s sustainability. | |

| 3.4. Average Euclidean distance | (A9) | Shows the average deviation of enterprises from the benchmark. | |

| 3.5. Taxonomic stability coefficient | (A10) | The closer the KT value is to 1, the higher the enterprise’s sustainability. | |

| Explanation of the notations in Appendix E: xij—actual value of the j-th indicator for the i-th enterprise; min(xi), max(xi)—minimum and maximum values of the xi indicator among all enterprises; zij—standardized value of the indicator after conversion to a dimensionless scale (from 0 to 1); z0—reference (ideal) vector containing the best indicator values for all parameters; x0j—reference value of the j-th indicator (the best possible level of sustainability); di—Euclidean distance between the i-th enterprise and the reference object, characterizing the degree of deviation from ideal sustainability; —average value of the distances di for all enterprises (the average deviation from the reference); s—standard deviation of the distances di, reflecting the degree of dispersion of sustainability among enterprises; KT—taxonomic sustainability coefficient, an integrated indicator reflecting the relative sustainability level of each enterprise compared to the benchmark. | |||

Appendix F. Summary of Hypothesis Testing Plan

| Hypothesis | Statistical Method | Formula | Justification | |

| H1. The implementation of adaptive financial management strategies and digital tools increases SME resilience. | Spearman’s correlation analysis | (A11) | The relationship between DLFO and RAS is tested. A positive ρ > 0.5 value confirms the hypothesis. | |

| H2. Access to external financing is a determining factor in survival. | t-test for independent samples | , where | (A12) | Average RAS values are compared for groups of companies with high and low AEFI levels. |

| H3. Geographic location influences financial resilience. | One-way ANOVA (analysis of variance) | (A13) | This test examines whether average RAS values differ between regions (Eastern, Central, Western). | |

| H4. Entrepreneurs with volunteer or military experience demonstrate a higher level of strategic resilience. | Mann–Whitney U-test | (A14) | This test is used if the RAS distribution is not normal; it compares entrepreneurs with and without experience in defense initiatives. | |

| Explanation of the notations in Appendix F: p—Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient; di—difference in the ranks of the variables (DLFO and RAS) for the i-th enterprise; n—number of observations (SMEs); t—Student’s t-statistic; —mean RAS values for the 1st and 2nd groups; Sp—pooled standard deviation; n1, n2—sizes of the 1st and 2nd samples; —variances of the 1st and 2nd samples; Yij—RAS value for the j-th enterprise in the i-th region; μ—overall mean RAS value. αi—effect of the i-th factor (region); εij—random error (residual); U—Mann–Whitney U-statistic; n1, n2—volumes of groups 1 and 2; R1—sum of the ranks of the RAS variable for the first group. | ||||

Appendix G. Code Scripts for Reproduction of Statistical Analyses

Appendix G.1. Data Preparation and Standardization (Python)

- import pandas as pd

- from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler

- df = pd.read_csv(“kpi_raw.csv”)

- kpi_cols = [“LR”,”DER”,”CFSI”,”RRR”,”OCIR”,”DLFO”,”AEFI”,”RAS”,”SREL”,”RRE”]

- X = df[kpi_cols]

- scaler = StandardScaler()

- X_z = scaler.fit_transform(X)

- df_z = pd.DataFrame(X_z, columns = [c+”_z” for c in kpi_cols])

Appendix G.2. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

- from sklearn.decomposition import PCA

- pca = PCA()

- pca.fit(X_z)

- loadings = pd.DataFrame(

- pca.components_.T,

- columns = [f”Factor{i+1}” for i in range(len(kpi_cols))],

- index = kpi_cols

- )

- explained_variance = pca.explained_variance_ratio_

Appendix G.3. K-Means Cluster Analysis

- from sklearn.cluster import KMeans

- kmeans = KMeans(n_clusters = 3, max_iter = 100, tol = 1 × 10−4, random_state = 42)

- clusters = kmeans.fit_predict(X_z)

- df[“Cluster”] = clusters

- centroids = kmeans.cluster_centers_

Appendix G.4. Taxonomic Benchmarking (KT Calculation)

- import numpy as np

- # min–max normalization

- df_norm = (X − X.min())/(X.max() − X.min())

- # ideal vector

- ideal = []

- for col in kpi_cols:

- if col in [“DER”,”OCIR”,”RRE”]: # negative indicators

- ideal.append(df_norm[col].min())

- else:

- ideal.append(df_norm[col].max())

- ideal = np.array(ideal)

- # distance to the ideal vector

- distances = np.sqrt(((df_norm.values − ideal)**2).sum(axis = 1))

- # taxonomic coefficient KT

- KT = 1 − distances/distances.max()

- df[“KT”] = KT

Appendix H. Calculation of the Taxonomic Coefficient of Sustainability (KT) of Small Enterprises in UKRAINE

| No. | Enterprise | di (Distance to the Standard) | KT (Stability Coefficient) | Cluster |

| 1 | LLC “AKVA-FISH KH” | 0.92 | 0.41 | 3 |

| 2 | FE “SANTONSKE” | 0.88 | 0.44 | 3 |

| 3 | FE “SEMILONSKE” | 0.81 | 0.50 | 3 |

| 4 | FE “FERMINSKE” | 0.75 | 0.56 | 3 |

| 5 | LLC “Semilon-Agro” | 0.89 | 0.43 | 3 |

| 6 | LLC “SANTON AGRO” | 0.80 | 0.51 | 3 |

| 7 | FE “EKOFUD-SLOBODA” | 0.83 | 0.48 | 3 |

| 8 | FE “POLUYIANIVSKE” | 0.70 | 0.60 | 3 |

| 9 | FE “TORINSKE” | 0.77 | 0.54 | 3 |

| 10 | FE “SOTON AGRO” | 0.95 | 0.38 | 3 |

| 11 | LLC “PRIMUS KOR” | 0.32 | 0.88 | 1 |

| 12 | LLC “SKYLIGHT” | 0.36 | 0.84 | 1 |

| 13 | LLC “AGROZEMTEKHPROEKT” | 0.28 | 0.91 | 1 |

| 14 | LLC “MK MedVyn” | 0.44 | 0.78 | 1 |

| 15 | CEC “AMARANT AGRO ZROSHENNIA” | 0.26 | 0.93 | 1 |

| 16 | LLC “AGRO OSTERS” | 0.52 | 0.72 | 1 |

| 17 | LLC “NEPTUNE FISH” | 0.40 | 0.81 | 1 |

| 18 | LLC “BT” | 0.30 | 0.90 | 1 |

| 19 | LLC “INKVILIN” | 0.38 | 0.83 | 1 |

| 20 | LLC “AGRO POINT GROUP” | 0.61 | 0.66 | 1 |

| 21 | FE “ZAKHIDNE OPYLLIA” | 0.25 | 0.94 | 2 |

| 22 | FE “SKAVA” | 0.41 | 0.80 | 2 |

| 23 | LLC “EKO-LISBUD” | 0.33 | 0.87 | 2 |

| 24 | FE MOHORUK K. M. | 0.37 | 0.84 | 2 |

| 25 | LLC “ULTRA FORCE” | 0.28 | 0.91 | 2 |

| 26 | FE “BUKOVIEN” | 0.47 | 0.76 | 2 |

| 27 | FE “ZAPIDOK” | 0.30 | 0.89 | 2 |

| 28 | FE “KUZHBA” | 0.58 | 0.68 | 2 |

| 29 | FE “V FILVAROK” | 0.50 | 0.74 | 2 |

| 30 | LLC “BEST BERRY” | 0.27 | 0.92 | 2 |

Appendix I. Technical Specifications of Analytical Procedures

Appendix I.1. Factor Analysis Parameters

- Method: Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

- Software: STATISTICA 13

- Rotation: None

- Factor loading threshold: >0.70

- Minimum eigenvalue criterion: 1.0

- Extraction rule: Kaiser normalization

- Standardization: Z-score normalization of all variables

- Purpose: Identification of latent determinants of SME financial resilience

Appendix I.2. Cluster Analysis Parameters

- Algorithm: K-means clustering

- Distance metric: Euclidean distance

- Number of clusters: 3 (determined using the elbow method)

- Maximum number of iterations: 100

- Convergence tolerance: 0.0001

- Software: STATISTICA 13

- Purpose: Classification of enterprises into resilience profiles

Appendix I.3. Taxonomic Benchmarking Parameters

- Normalization procedure: Min–max scaling to the interval [0, 1]

- Distance metric: Multivariate Euclidean distance

- Reference (ideal) vector:

- Maximum values for positive indicators

- Minimum values for negative indicators (DER, OCIR, RRE)

- Stability coefficient: Calculated using Formula (10)

- Purpose: Construction of the integral resilience indicator (KT)

Appendix I.4. Extended Statistical Outputs and Supplementary Tables

Appendix I.4.1. Full PCA Eigenvalue Table

| Component | Eigenvalue | Variance Explained (%) | Cumulative (%) |

| 1 | 4.82 | 48.2 | 48.2 |

| 2 | 2.19 | 21.9 | 70.1 |

| 3 | 1.00 | 10.0 | 80.1 |

| 4 | 0.71 | 7.1 | 87.2 |

| 5 | 0.52 | 5.2 | 92.4 |

| 6 | 0.34 | 3.4 | 95.8 |

| 7 | 0.22 | 2.2 | 98.0 |

| 8 | 0.12 | 1.2 | 99.2 |

| 9 | 0.05 | 0.5 | 99.7 |

| 10 | 0.03 | 0.3 | 100.0 |

Appendix I.4.2. Full Factor Loadings Matrix

| Indicator | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 |

| LR | 0.78 | 0.12 | 0.05 |

| DER | –0.81 | 0.05 | 0.18 |

| CFSI | 0.85 | 0.16 | –0.11 |

| RRR | 0.72 | 0.40 | –0.03 |

| OCIR | –0.76 | –0.12 | 0.09 |

| DLFO | 0.43 | 0.75 | 0.21 |

| AEFI | 0.55 | 0.66 | –0.18 |

| RAS | 0.47 | 0.69 | 0.22 |

| SREL | 0.58 | 0.41 | 0.35 |

| RRE | –0.64 | –0.19 | 0.42 |

Appendix I.4.3. Cluster Membership Distances (K-Means)

| Enterprise ID | Cluster | Distance to Centroid |

| 1 | 3 | 0.41 |

| 2 | 3 | 0.38 |

| 3 | 3 | 0.52 |

| 4 | 1 | 0.47 |

| 5 | 3 | 0.44 |

| 6 | 3 | 0.49 |

| 7 | 3 | 0.46 |

| 8 | 1 | 0.35 |

| 9 | 1 | 0.39 |

| 10 | 3 | 0.58 |

| 11 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 12 | 2 | 0.36 |

| 13 | 2 | 0.31 |

| 14 | 1 | 0.42 |

| 15 | 2 | 0.29 |

| 16 | 1 | 0.45 |

| 17 | 2 | 0.34 |

| 18 | 2 | 0.32 |

| 19 | 2 | 0.37 |

| 20 | 1 | 0.51 |

| 21 | 2 | 0.28 |

| 22 | 1 | 0.40 |

| 23 | 2 | 0.35 |

| 24 | 2 | 0.33 |

| 25 | 2 | 0.30 |

| 26 | 1 | 0.48 |

| 27 | 2 | 0.31 |

| 28 | 1 | 0.53 |

| 29 | 1 | 0.44 |

| 30 | 2 | 0.44 |

Appendix I.4.4. Distribution of Taxonomic Distances

| Indicator | Mean Distance | Min | Max |

| d(i, ideal) | 0.41 | 0.21 | 0.78 |

Appendix I.4.5. Sensitivity Analysis of KT

| Scenario | Adjustment | KT Mean | KT Range |

| Base | none | 0.67 | 0.38–0.94 |

| +10% weight to financial KPIs | +10% | 0.70 | 0.41–0.96 |

| +10% weight to operational KPIs | +10% | 0.64 | 0.36–0.91 |

References

- Adomako, S. (2020). Resource-induced coping heuristics and entrepreneurial orientation in dynamic environments. Journal of Business Research, 122, 477–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aidoo, S. O., Agyapong, A., Acquaah, M., & Akomea, S. Y. (2021). The performance implications of strategic responses of SMEs to the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from an African economy. Africa Journal of Management, 7(1), 74–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyabe, M. F., Arranz, C. F., De Arroyabe, I. F., & De Arroyabe, J. C. F. (2024). Analyzing AI adoption in European SMEs: A study of digital capabilities, innovation, and external environment. Technology in Society, 79, 102733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atiase, V. Y., Agbanyo, S., Ganza, P., & Sambian, R. M. (2022, October 27–28). Investigating financial resilience and survivability of SMEs in Africa: A panel study. ISBE 2022: New Approaches to Raising Entrepreneurial Opportunity: Reshaping inclusive Enterprise, Policy, and Practice Post-Pandemic, York, UK. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/364835995_Investigating_Financial_Resilience_and_Survivability_of_SMEs_in_Africa_A_Panel_Study (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Benmelech, E., & Frydman, C. (2014). Military CEOs. Journal of Financial Economics, 117(1), 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butko, M., & Zakharchenko, A. (2025). Specifics of small and medium-sized business development in modern conditions. Scientific Bulletin of Polissia, 1(30), 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cefis, E., Bettinelli, C., Coad, A., & Marsili, O. (2022). Understanding firm exit: A systematic literature review. Small Business Economics, 59, 423–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crecente, F., Sarabia, M., & Del Val, M. T. (2020). The hidden link between entrepreneurship and military education. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 163, 120429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeTienne, D. R. (2008). Entrepreneurial exit as a critical component of the entrepreneurial process: Theoretical development. Journal of Business Venturing, 25(2), 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeTienne, D. R., McKelvie, A., & Chandler, G. N. (2014). Making sense of entrepreneurial exit strategies: A typology and test. Journal of Business Venturing, 30(2), 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dligach, A., & Stavytskyy, A. (2024). Resilience factors of Ukrainian Micro, Small, and Medium-Sized business. Economies, 12(12), 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatab, A. A., & Lagerkvist, C. (2024). Perceived business risks and observed impacts of the Russian-Ukraine war among small- and medium-sized agri-food value chain enterprises in Egypt. Food Policy, 127, 102712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynie, J. M., & Shepherd, D. (2010). Toward a theory of discontinuous career transition: Investigating career transitions necessitated by traumatic life events. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(3), 501–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helwig, N. (2023). EU strategic autonomy after the Russian invasion of Ukraine: Europe’s capacity to act in times of war. JCMS Journal of Common Market Studies, 61(S1), 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J.-P., & Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmaker, C. L., Aziz, R. A., Palit, T., & Bari, A. B. M. M. (2022). Analyzing supply chain risk factors in the small and medium enterprises under fuzzy environment: Implications towards sustainability for emerging economies. Sustainable Technology and Entrepreneurship, 2(1), 100032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolodiziev, O., Dorokhov, O., Shcherbak, V., Dorokhova, L., Ismailov, A., & Figueiredo, R. (2024a). Resilience benchmarking: How small hotels can ensure their survival and growth during global disruptions. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(7), 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolodiziev, O., Shcherbak, V., Kostyshyna, T., Krupka, M., Riabovolyk, T., Androshchuk, I., & Kravchuk, N. (2024b). Digital transformation as a tool for creating an inclusive economy in Ukraine during wartime. Problems and Perspectives in Management, 22(3), 440–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanivich, S. E. (2013). The RICH entrepreneur: Using conservation of resources theory in contexts of uncertainty. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(4), 863–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, A., Eller, R., & Peters, M. (2024). Creating competitiveness in incumbent small- and medium-sized enterprises: A revised perspective on digital transformation. Journal of Business Research, 186, 115028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odoch, H. J., Namono, R., & Wofuma, G. (2025). Enhancing financial resilience of women-owned SMEs in the aftermath of COVID-19 pandemic: The antecedent role of social capital. Vilakshan—XIMB Journal of Management, 22(1), 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2023). OECD economic outlook (Vol. 2023, Issue 2). OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M. E. (2000). Location, competition, and economic development: Local clusters in a global economy. Economic Development Quarterly, 14(1), 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardeshmukh, S. R., Goldsby, M., & Smith, R. M. (2018). Are work stressors and emotional exhaustion driving exit intentions among business owners? Journal of Small Business Management, 59(4), 544–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shcherbak, V., Danko, Y., Tereshchenko, S., Nifatova, O., Dehtiar, N., Stepanova, O., & Yatsenko, V. (2024). Circular economy and inclusion as effective tools to prevent ecological threats in rural areas during military operations. Global Journal of Environmental Science and Management, 10(3), 969–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shcherbak, V., Dorokhov, O., Ukrainski, K., Kovbasa, O., Pietukhov, A., & Dorokhova, L. (2025). Social responsibility of financial support for refugee and migrant startups in the Baltics. SSRN. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5077650 (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Shenderivska, L., Guk, O., & Mokhonko, H. (2022). Transformation of business models of publishing house in the conditions of war and pandemic. Economic Scope, 179, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, D. A., & Williams, T. A. (2014). Local venturing as compassion organizing in the aftermath of a natural disaster: The role of localness and community in reducing suffering. Journal of Management Studies, 51(6), 952–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M. K., Sárközy, H., Singh, S. K., & Zéman, Z. (2022). Impact of Ukraine-Russia war on global trade and development: An empirical study. Acta Academiae Beregsasiensis Economics, 1, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, E., & Li, Z. (2024). The impact of entrepreneurs’ military experience on small business exit: A conservation of resources perspective. Journal of Business Research, 186, 115004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ucbasaran, D., Shepherd, D. A., Lockett, A., & Lyon, S. J. (2012). Life after business failure. Journal of Management, 39(1), 163–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDP. (2022). Human development report 2021/2022: Uncertain times, unsettled lives: Shaping our future in a transforming world (overview). United Nations Development Programme. Available online: https://hdr.undp.org/system/files/documents/global-report-document/hdr2021-22overviewen.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Wennberg, K., Wiklund, J., DeTienne, D. R., & Cardon, M. S. (2009). Reconceptualizing entrepreneurial exit: Divergent exit routes and their drivers. Journal of Business Venturing, 25(4), 361–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T. A., & Shepherd, D. A. (2016). Victim entrepreneurs doing well by doing good: Venture creation and well-being in the aftermath of a resource shock. Journal of Business Venturing, 31(4), 365–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2023, June 27). World Bank provides financing for viable micro, small and medium sized firms in Türkiye. World Bank Press Release. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2023/06/27/world-bank-provides-financing-for-viable-micro-small-and-medium-sized-firms-in-turkiye (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Xu, Z., Li, B., Liu, Z., & Wu, J. (2021). Previous military experience and entrepreneurship toward poverty reduction: Evidence from China. Management Decision, 60(7), 1969–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| № | Indicator | Abbreviation | Description | Thresholds/Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Liquidity Ratio | LR | Liquidity ratio—reflects a company’s ability to meet short-term obligations. | >1.5—good; 1.0–1.5—satisfactory; <1.0—problematic. |

| 2 | Debt-to-Equity Ratio | DER | Debt-to-equity ratio, which characterizes the level of financial dependence. | <1.0—low debt; 1.0–2.0—moderate; >2.0—high. |

| 3 | Cash Flow Stability Index | CFSI | Cash flow stability indicator—reflects a company’s ability to maintain a positive cash balance. | Scale 0–1. Closer to 1 indicates greater stability. |

| 4 | Revenue Recovery Rate | RRR | Revenue recovery compared to the pre-war period. | Percentage (%) of recovery relative to pre-crisis (2021) level. |

| 5 | Operational Cost Increase Rate | OCIR | Operating cost growth rate due to military operations and logistical constraints. | Percentage (%) increase relative to pre-crisis period. |

| 6 | Digitalization Level of Financial Operations | DLFO | Share of digital financial transactions (online payments, electronic reporting, CRM systems). | Scale 1–5; 1—low, 5—high. |

| 7 | Access to External Finance Index | AEFI | Assessment of the availability of loans, grants, and donor programs. | Scale 1–5; 1—very low, 5—very high. |

| 8 | Resilience Adaptation Score | RAS | An integrated indicator reflecting a company’s ability to adapt to changing market conditions. | Scale 1–10; higher score indicates greater resilience. |

| 9 | Social Responsibility Engagement Level | SREL | Level of company involvement in socially responsible initiatives and volunteer programs. | Scale 1–5; 1—low, 5—high. |

| 10 | Regional Risk Exposure | RRE | Regional exposure to military and security risks, based on conflict intensity indices and proximity to frontline zones. | Scale 1–10; higher value indicates greater risk exposure (e.g., 9–10 = frontline, 3–5 = low-risk western regions). |

| Procedure | Software | Key Parameters | Convergence Criteria | Output Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor Analysis | STATISTICA 13 | KMO = 0.87; Bartlett’s test: p < 0.001; eigenvalue > 1.0 | Eigenvalue > 1.0 | 90.1% variance explained |

| Cluster Analysis | STATISTICA 10 | k = 3; max iterations = 100 | Centroid change < 0.0001 | Silhouette score = 0.72 |

| Taxonomic Method | Python 3.10 | Min–max normalization; Euclidean distance | Benchmark vector stability check | KT coefficient range: 0.38–0.94 |

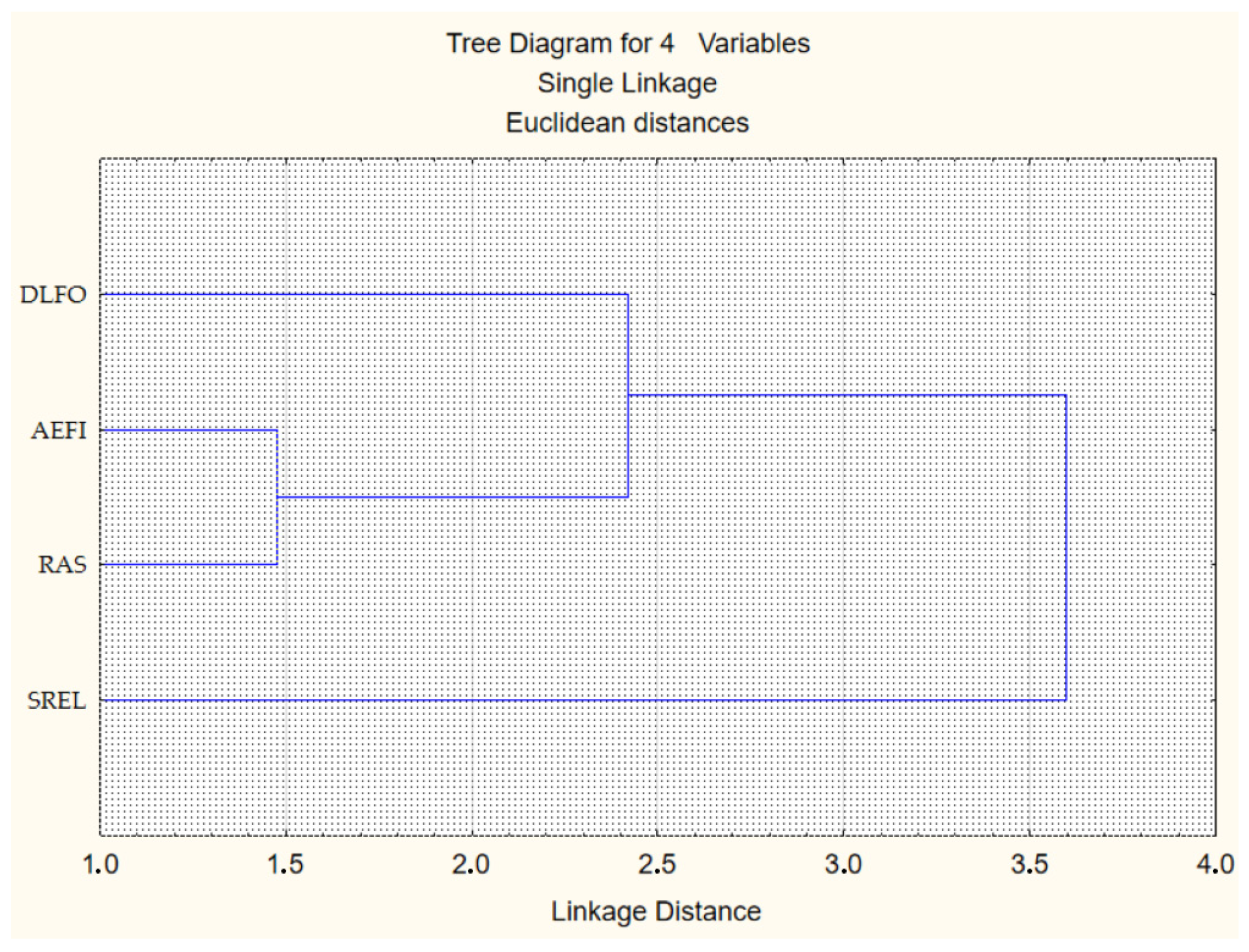

| Variable | Factor Loadings (Unrotated) (Data_nor) Extraction: Principal Components (Marked Loadings Are >0.700000) |

|---|---|

| Factor 1 | |

| LR | −0.984165 |

| DER | 0.982099 |

| CFSI | −0.982463 |

| RRR | −0.993300 |

| OCIR | 0.986691 |

| DLFO | −0.885731 |

| AEFI | −0.963329 |

| RAS | −0.989024 |

| SREL | −0.801629 |

| RRE | 0.902614 |

| Expl.Var | 9.00655 |

| Prp.Totl | 0.900654 |

| Members of Cluster Number 1 (Data_nor) and Distances from Respective Cluster Center Cluster Contains 10 Cases | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Case No. | Distance | Case No. | Distance |

| C_4 | 0.4556115 | C_20 | 0.5531445 |

| C_8 | 0.3167202 | C_22 | 0.4265745 |

| C_9 | 0.5314636 | C_26 | 0.5478812 |

| C_14 | 0.4426546 | C_28 | 0.4241928 |

| C_16 | 0.2676535 | C_29 | 0.6909757 |

| Members of Cluster Number 2 (Data_Nor) And Distances From Respective Cluster Center Cluster Contains 13 Cases | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Case No. | Distance | Case No. | Distance |

| C_11 | 0.266444 | C_21 | 0.5324675 |

| C_12 | 0.420495 | C_23 | 0.3203908 |

| C_13 | 0.373412 | C_24 | 0.5405027 |

| C_15 | 0.3476844 | C_25 | 0.3465283 |

| C_17 | 0.3587299 | C_27 | 0.2404362 |

| C_18 | 0.3822872 | C_30 | 0.3606293 |

| C_19 | 0.3733964 | ||

| Members of Cluster Number 3 (Data_nor) and Distances from Respective Cluster Center Cluster Contains 7 Cases | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Case No. | Distance | Case No. | Distance |

| C_1 | 0.3773603 | C_6 | 0.5552688 |

| C_2 | 0.3879911 | C_7 | 0.3017505 |

| C_3 | 0.4188683 | C_10 | 0.7467695 |

| C_5 | 0.3725443 | ||

| Indicators | Spearman’s Coefficient (ρ) | p-Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| DLFO vs. RAS | 0.898 | 0.0000 | Strong positive correlation |

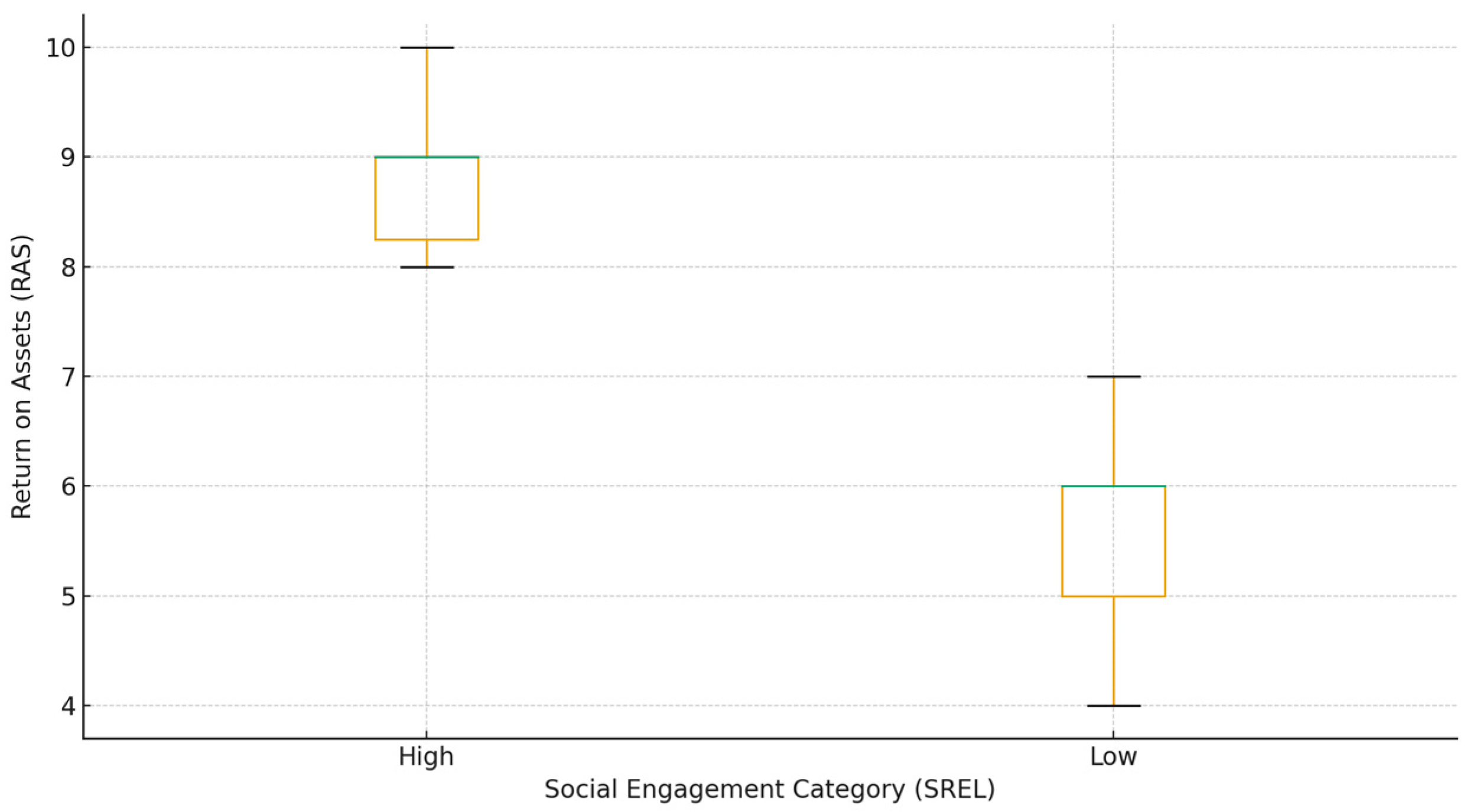

| Indicator | Group 1: High Engagement (SREL ≥ 4) | Group 2: Low Engagement (SREL ≤ 3) | Justification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of observations (n1, n2) | n1 = 9 | n2 = 17 | Division by level of social activity |

| Mean RAS | 8.56 | 6.00 | Entrepreneurs with high engagement demonstrate higher resilience |

| Median RAS | 9 | 6 | Confirms the shift in distribution |

| Standard Deviation | 1.17 | 2.01 | Greater variation in the low engagement group |

| Rank Sum (R1, R2) | R1 = 256 | R2 = 149 | Higher rank sum in the high SREL group |

| U Statistic (calculated by formula 14) | U1 = 28 | U2 = 125 | Minimum U value used for comparison |

| Critical U Value (α = 0.05) | Ucrit = 37 | For n1 = 9 and n2 = 17 | |

| Decision | U1 < Ucrit → H0 rejected | Difference is statistically significant | |

| Interpretation | Entrepreneurs with high SREL demonstrate significantly higher strategic resilience | Hypothesis H4 is confirmed |

| Cluster | Main Characteristics | Predominant Region | Average KT | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1 | Medium liquidity and digitalization, moderate risks | Central | 0.81 | Balanced strategies focused on maintaining stability |

| Cluster 2 | High DLFO, AEFI, and RAS values | Western | 0.89 | Most resilient enterprises with access to external financing |

| Cluster 3 | Low DLFO and RAS, high debt load | Eastern | 0.49 | Vulnerable enterprises requiring targeted support and credit guarantees |

| Indicator | LR | DLFO | AEFI | RAS | SREL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LR | 1.00 | 0.68 | 0.72 | 0.65 | 0.59 |

| DLFO | 0.68 | 1.00 | 0.74 | 0.83 | 0.61 |

| AEFI | 0.72 | 0.74 | 1.00 | 0.79 | 0.64 |

| RAS | 0.65 | 0.83 | 0.79 | 1.00 | 0.58 |

| SREL | 0.59 | 0.61 | 0.64 | 0.58 | 1.00 |

| Region | Average KT | Average RRE | Risk Level | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Western | 0.89 | 0.15 | Low | High resilience, active digitalization, EU and grant program support |

| Central | 0.81 | 0.37 | Medium | Balanced indicators but dependent on domestic demand |

| Eastern | 0.49 | 0.68 | High | Low resilience, significant impact of military risks and resource shortages |

| Cluster | Main Enterprise Characteristics | Key Risks | Strategic Priorities | Risk Management System Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1—Medium Resilience (Central Region, KT ≈ 0.81) | Balanced liquidity and debt indicators; moderate digitalization; high social engagement | Dependence on domestic demand; limited access to external financing | Increase financial flexibility and operational efficiency | Develop stress-testing systems to assess the impact of reduced domestic demand; implement ERP systems for financial planning; create reserve funds to cover cash gaps; strengthen ties with regional funds and business incubators |

| Cluster 2—High Resilience (Western Region, KT ≈ 0.89) | High liquidity, active digitalization, high RAS, access to grants and credit | Currency fluctuations, rising energy costs | Strengthen innovation and export resilience | Create a multi-level monitoring system for currency risks; implement contract hedging and supplier diversification; develop digital platforms to monitor cash flows; participate in European grant and acceleration programs (Horizon Europe, EBRD, USAID) |

| Cluster 3—Low Resilience (Eastern Region, KT ≈ 0.49) | Low access to financing, high debt load, low liquidity, high regional risk exposure | Loss of markets, logistical disruptions, infrastructure damage | Financial recovery and cooperative integration | Introduce government guarantees for SME loans and targeted microfinance programs; develop cooperative networks for joint resource use; apply digital tools for supply chain and inventory management; create regional crisis consulting centers at OVAs and Chambers of Commerce |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Shcherbak, V.; Dorokhov, O.; Dorokhova, L.; Vzhytynska, K.; Yatsenko, V.; Yermolenko, O. Financial Risk Management and Resilience of Small Enterprises Amid the Wartime Crisis. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2026, 19, 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm19010037

Shcherbak V, Dorokhov O, Dorokhova L, Vzhytynska K, Yatsenko V, Yermolenko O. Financial Risk Management and Resilience of Small Enterprises Amid the Wartime Crisis. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2026; 19(1):37. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm19010037

Chicago/Turabian StyleShcherbak, Valeriia, Oleksandr Dorokhov, Liudmyla Dorokhova, Kseniia Vzhytynska, Valentyna Yatsenko, and Oleksii Yermolenko. 2026. "Financial Risk Management and Resilience of Small Enterprises Amid the Wartime Crisis" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 19, no. 1: 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm19010037

APA StyleShcherbak, V., Dorokhov, O., Dorokhova, L., Vzhytynska, K., Yatsenko, V., & Yermolenko, O. (2026). Financial Risk Management and Resilience of Small Enterprises Amid the Wartime Crisis. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 19(1), 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm19010037