Readiness and Perceptions of IPSAS 46 “Measurement” Implementation in Public Sector Entities: Evidence from Georgia

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Problem

1.2. Purpose of the Study

- Public sector practitioners’ perceptions of IPSAS 46 and its measurement principles;

- The extent of organizational readiness—technical, institutional, and cognitive—to implement the standard;

- The key challenges and capacity gaps shaping adoption prospects.

1.3. Theoretical Contribution

- It proposes a theory-informed analytical framework of readiness for measurement reforms, integrating institutional theory (DiMaggio & Powell, 2000), change readiness frameworks (Holt et al., 2007), and valuation theory applied to the public sector.

- It extends the literature on public sector measurement uncertainty, offering empirical insights into how practitioners interpret current value measurement requirements and associated challenges (Polzer et al., 2021).

- It provides the first empirical evidence on IPSAS 46 readiness, addressing a significant gap in both international and local scholarship.

1.4. Research Questions

1.5. Practical Contribution

1.6. Structure of the Paper

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Institutional Theory and Public Sector Accounting Change

2.2. Readiness for Change: A Multidimensional Construct

- Change Commitment—belief that the reform is necessary and beneficial;

- Change Efficacy—belief in the organization’s ability to successfully implement it;

- Task-Specific Competence—technical capacity to perform new measurement tasks;

- Resource Availability—financial, human, and informational resources to support adoption (Wang, 2014).

2.3. Measurement Complexity and Valuation Theory in the Public Sector

- Technical Complexity—difficulty in applying measurement techniques that require specialized expertise or judgment;

- Data and Information Constraints—lack of market data, asset condition information, or historical cost structures;

- Cognitive Uncertainty—ambiguity in interpreting valuation guidance or selecting measurement base (ICAEW, 2023). These constraints frequently result in inconsistent or unreliable valuations, leading to reduced comparability and skepticism among practitioners (Oulasvirta, 2014). Understanding practitioners’ perceptions of complexity is therefore central to assessing readiness for IPSAS 46 (IPSASB, 2021).

2.4. Organizational Factors Shaping IPSAS 46 Readiness

- (a)

- Technical Capacity

- (b)

- Institutional Support and Governance

- (c)

- Resource Availability

- (d)

- Professional Competence and Training

2.5. Conceptual Model of Readiness for IPSAS 46

- Institutional Pressures → motivation to adopt measurement reforms;

- Technical Capacity → capability to perform valuation;

- Professional Competence → knowledge and judgment required for IPSAS 46;

- Perceived Measurement Complexity → cognitive and practical barriers.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Epistemological Positioning

3.3. Sampling Strategy and Participants

- Accountants and financial managers from budgetary organizations;

- Employees responsible for asset management and valuation;

- Representatives of public entities expected to apply IPSAS 46 in practice.

3.4. Instrument Design and Construct Mapping

- Institutional Support and Governance

- −

- Perceived leadership commitment, internal guidelines, and organizational prioritization;

- Technical Capacity

- −

- Availability of IT systems, data quality, and valuation tools;

- Professional Competence

- −

- Practitioners’ knowledge, experience, and training related to IPSAS and measurement techniques;

- Perceived Measurement Complexity

- −

- Difficulty interpreting IPSAS 46 requirements, valuation uncertainty, and cognitive load.

“How important do you consider governmental or institutional involvement (e.g., provision of licensed valuation services, methodological guidance, or financial support) for the implementation of IPSAS 46?”

3.5. Data Analysis Strategy

- Variables represent categorical perceptions or readiness indicators;

- Sample size is sufficient to meet the minimum expected-cell conditions;

- The goal is to identify statistically significant associations, not causality (Agresti, 2019).

3.6. Reliability, Validity, and Limitations

3.6.1. Reliability

3.6.2. Construct Validity

- Theoretical mapping of items to conceptual dimensions;

- Expert review of instrument content;

- Alignment with IPSAS measurement requirements and readiness theory.

3.6.3. Internal Validity

3.6.4. External Validity

3.6.5. Limitations

- Self-reported data may be affected by social desirability bias.

- Purposive sampling restricts generalizability.

- The novelty of IPSAS 46 means that some respondents may lack full familiarity, influencing perceptions.

4. Results and Interpretation

4.1. Overview of Data Patterns

- IPSAS knowledge levels;

- Perceived institutional support;

- Resource availability;

- Attitudes toward the feasibility of implementing IPSAS 46.

4.2. Professional Knowledge and Support for IPSAS Adoption

- Institutional theory suggests that norms and professional identities shape acceptance of reforms. Greater knowledge strengthens normative alignment, making practitioners more receptive to institutional change (Benito et al., 2007).

- Readiness-for-change theory (Holt et al., 2007) emphasizes change efficacy: knowledge enhances confidence in applying IPSAS 46, increasing perceived feasibility.

- The finding is consistent with prior evidence that competence is a primary determinant of IPSAS adoption success (Caruana et al., 2019).

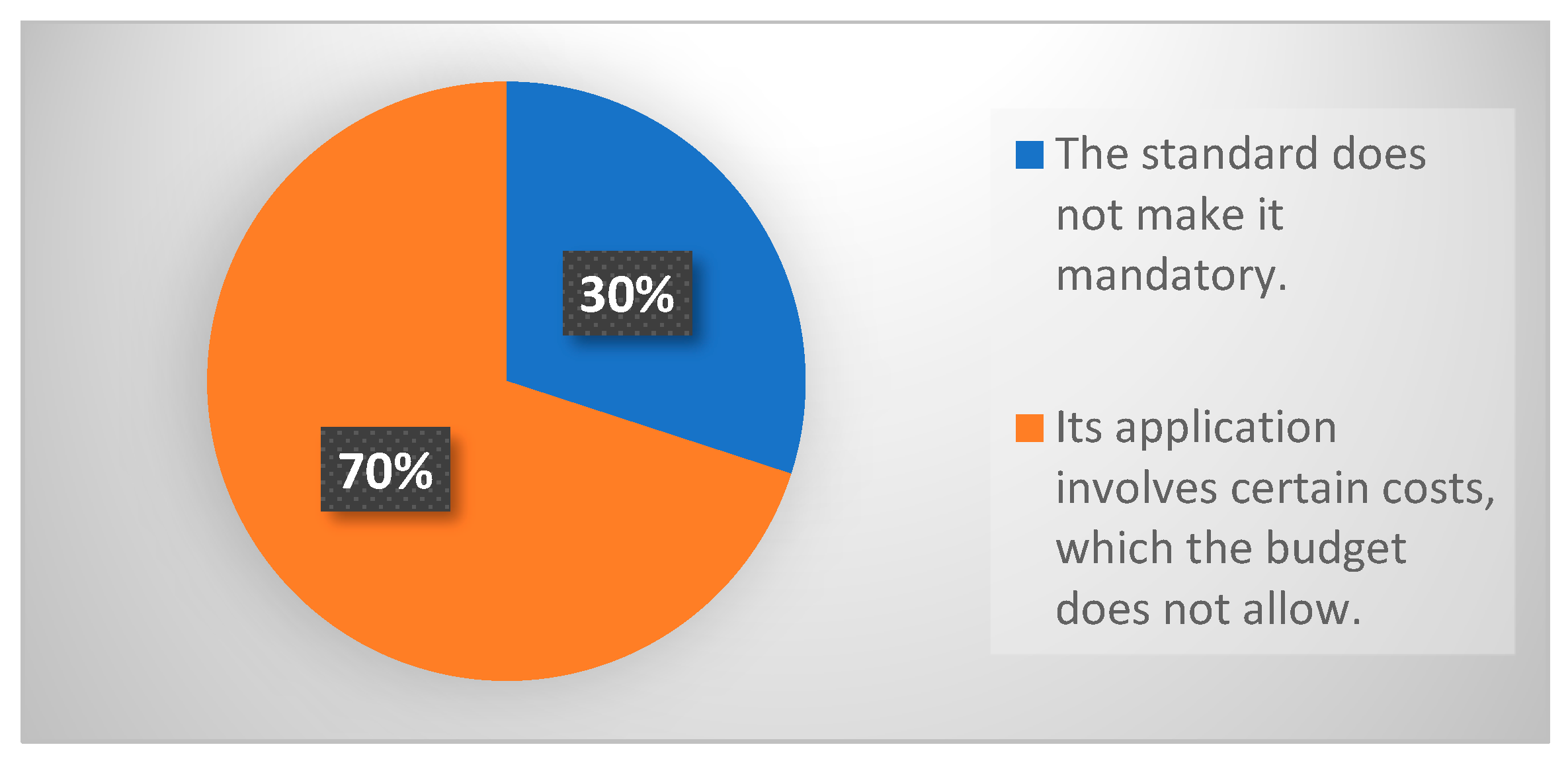

4.3. Resource Constraints and Perceived Feasibility of Measurement

- Institutional capacity theory predicts that reforms requiring high-cost technical expertise—such as fair value and current operational value—are more difficult to implement in resource-constrained settings (Boka, 2010).

- Valuation theory highlights that the absence of budgetary resources restricts access to licensed valuers and impedes the generation of reliable measurement inputs (Polzer et al., 2021).

- Readiness theory positions resource availability as one of the core antecedents of organizational readiness.

4.4. Institutional Support and Institutional Readiness

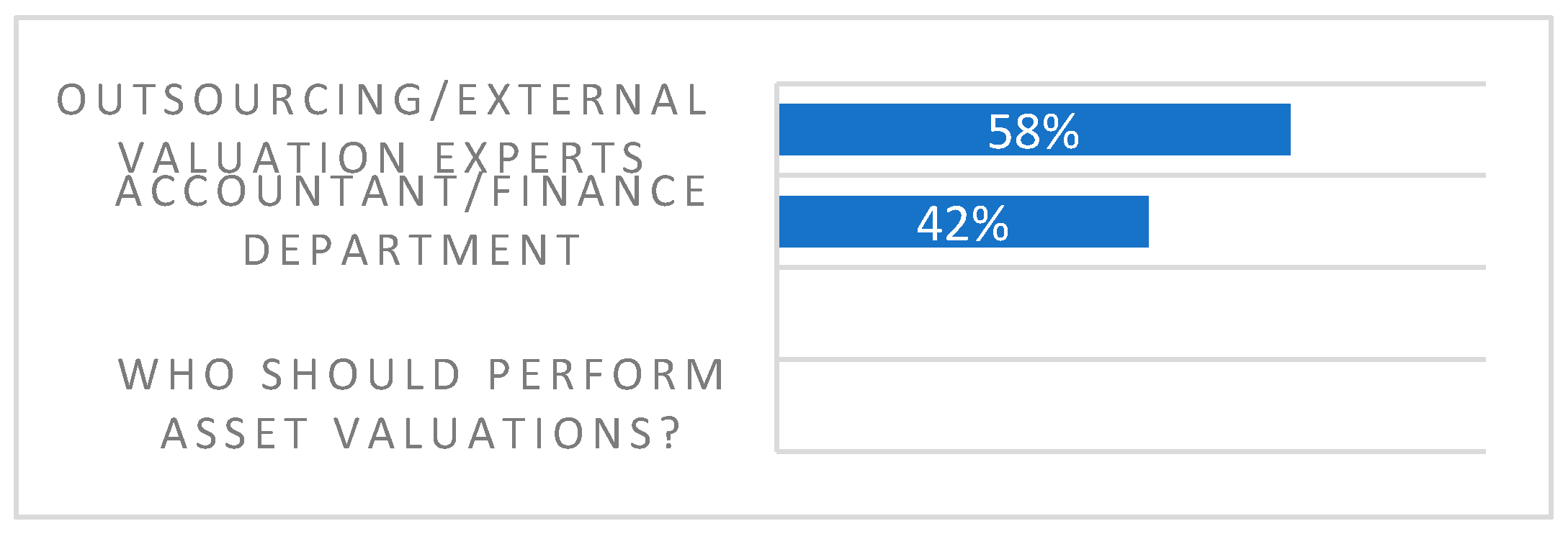

- Valuation must legally be conducted by licensed independent experts rather than government bodies (Sabauri, 2024).

- Government support is therefore indirect—legal frameworks, funding mechanisms, and policy alignment.

- The findings demonstrate the following:

- Practitioners who perceive stronger governmental coordination show higher readiness.

- Institutional legitimacy and clear governance structures function as catalysts for change (Caperchione et al., 2016).

4.5. Integrated Interpretation: Institutional, Professional, and Organizational Dynamics

| Determinant | Evidence | Interpretation |

| Professional knowledge | χ2 significant; higher knowledge = higher support | Strengthens cognitive readiness and reform legitimacy |

| Resource availability | χ2 significant; budget scarcity = lower readiness | Structural barrier that limits measurement capability |

| Institutional support | χ2 significant; perceived support = higher readiness | Enhances normative pressure and reduces uncertainty |

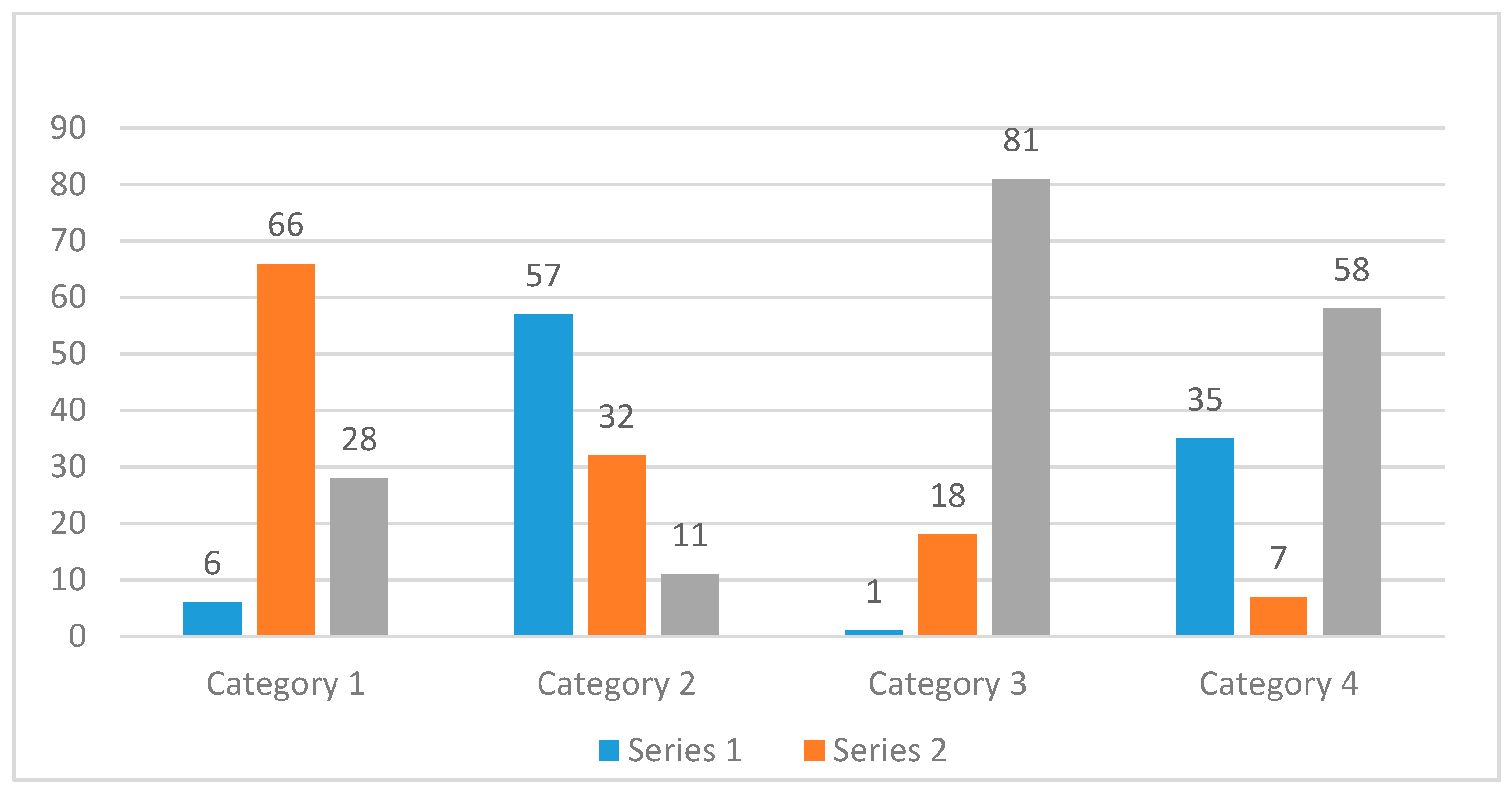

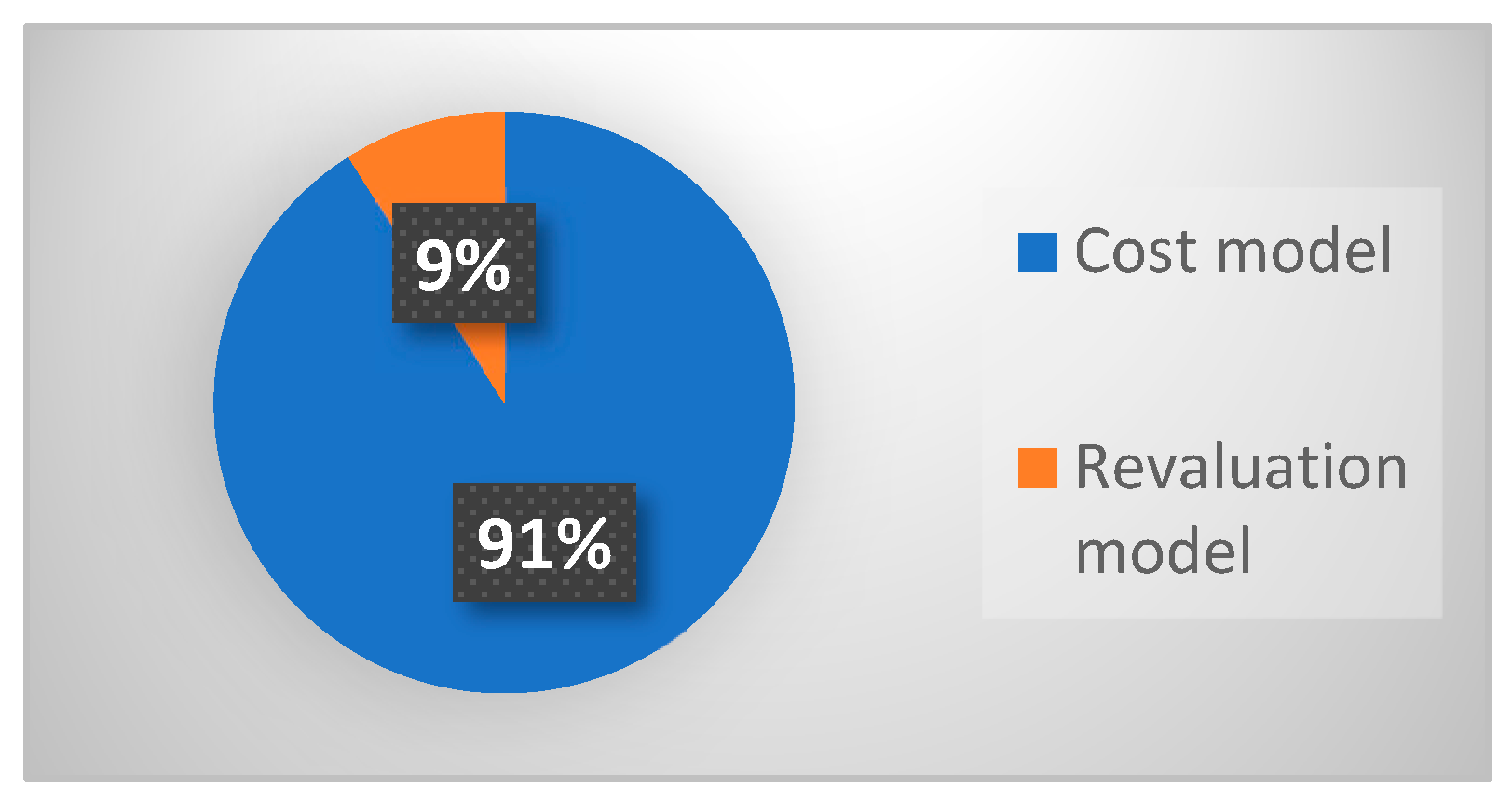

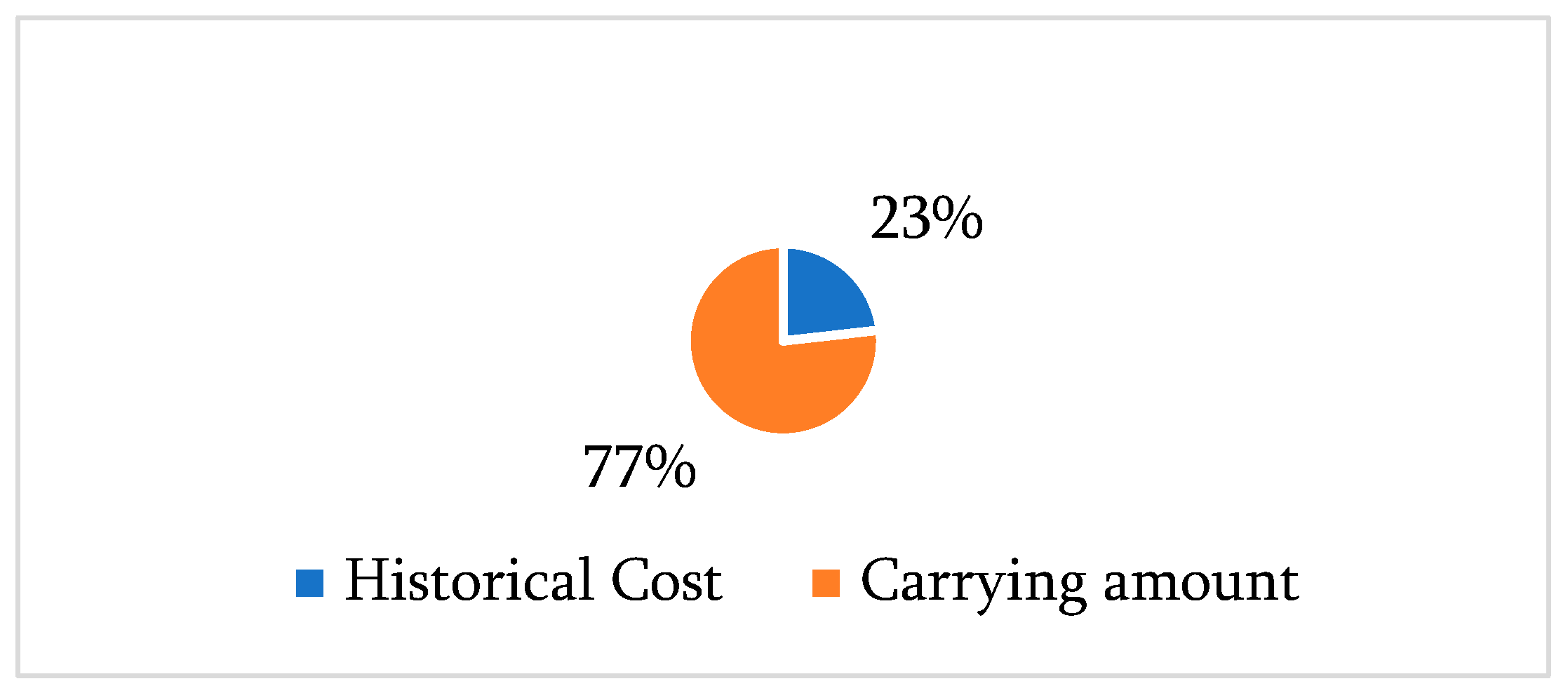

4.6. Visualization of Key Findings

4.7. Synthesis: Why Measurement Reform Remains Difficult

- The adoption of IPSAS 46 requires new technical capabilities;

- Institutional coherence;

- Financial investment;

- Professional transformation.

5. Discussion and Contributions

5.1. Interpreting Readiness Through Institutional Theory

5.2. Professional Competence as a Core Mechanism of Readiness

5.3. Resource Constraints as Structural Barriers to Measurement Reforms

- Licensed valuers;

- Specialized assessment tools;

- Consistent market data;

- Significant organizational investment.

5.4. Measurement Complexity and Cognitive Barriers

- Cognitive load—Practitioners experience difficulty interpreting IPSAS 46 guidance due to the abstract nature of current value measurement and the judgment required to select appropriate bases.

- Perceptual risk—Respondents perceive a greater risk of misstatement or audit challenge when applying valuation techniques in settings with limited data.

5.5. Integrating Findings into a Theoretical Model of IPSAS 46 Readiness

- Institutional legitimacy influences readiness but does not translate into implementation without the following:

- ○

- Adequate technical capacity;

- ○

- Sufficient resources;

- ○

- Strong professional competence.

- Professional knowledge enhances both attitudinal support and perceived capacity, serving as the cognitive pathway through which institutional expectations become operational reality.

- Resource constraints act as a moderating factor that weakens institutional influence and reduces readiness even in supportive environments.

- Measurement complexity forms a separate cognitive barrier that reinforces resistance or cautious attitudes toward IPSAS 46 implementation.

5.6. Theoretical Contributions

- Conceptual Expansion of Readiness Theory

- 2.

- Empirical Evidence on IPSAS 46 Implementation

- 3.

- Advancement of Public Sector Measurement Theory

5.7. Practical and Policy Contributions

- Targeted training programs should focus not only on IPSAS knowledge but also on valuation judgment and measurement methodology.

- Government agencies must provide stronger institutional support, including clear implementation guidelines and financial allocations.

- Public entities should invest in data systems and valuation tools to support current value measurement.

- Regulators may consider the phased implementation of IPSAS 46 to mitigate capacity gaps.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- ACCA. (2017). IPSAS implementation: Current status and challenges. Available online: https://www.accaglobal.com/pk/en/professional-insights/global-profession/ipsas-implementation-current-status-and-challenges.html (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Ada, S. S., & Christiaens, J. (2018). The magic shoes of IPSAS: Will they fit Turkey? Available online: https://scispace.com/pdf/the-magic-shoes-of-ipsas-will-they-fit-turkey-512hi6wi4a.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Agresti, A. (2019). An introduction to categorical data analysis (3rd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. Available online: https://users.stat.ufl.edu/~aa/cda/solutions-part.pdf (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Alessa, N. (2024). Exploring the effect of international public sector accounting standards adoption on national resource allocation efficiency in developing countries. Public and Municipal Finance, 13(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armenakis, A. A., & Harris, S. G. (2009). Reflections: Our journey in organizational change research and practice. Journal of Change Management, 9(2), 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascani, I., Ciccola, R., & Chiucchi, M. S. (2021). A structured literature review about the role of management accountants in sustainability accounting and reporting. Sustainability, 13(4), 2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azegagh, J., & Zyani, M. (2024). Accrual accounting and IPSAS implementation in developing countries: The Moroccan case. Revue Française d’Économie et de Gestion, 5(9), 173–183. [Google Scholar]

- Babatunde, S. A., Aderibigbe, A. A., & Fadairo, I. O. (2025). IPSAS and financial accountability relationship in public finance management. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/398109601 (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Beke-Trivunac, J., & Živkov, E. (2024). Measurement of assets and liabilities under the IAS/IPSAS conceptual framework. Revizor, 27(108), 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito, B., Brusca, I., & Montesinos, V. (2007). The harmonization of government financial information systems: The role of the IPSASs. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 73(2), 293–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boka, M. (2010). On the international convergence of accounting standards. International Journal of Business and Management, 5(4), 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caperchione, E., Brusca, I., Cohen, S., & Manes Rossi, F. (2016). Editorial: Innovations in public sector financial management. International Journal of Public Sector Performance Management, 2(4), 303–309. [Google Scholar]

- Caruana, J., Brusca, I., Caperchione, E., & Manes Rossi, F. (2019). Exploring the relevance of accounting frameworks in the pursuit of financial sustainability of public sector entities: A holistic approach. In Financial sustainability of public sector entities. Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenar, I., & Cioban, E. (2022). Implementation of international public sector accounting standards (IPSAS): Variables and challenges, advantages and disadvantages. Annals of the University of Petroşani, Economics, 22(1), 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, C. M., McDonald, R., Altman, E. J., & Palmer, J. E. (2018). Disruptive innovation: An intellectual history and directions for future research. Journal of Management Studies, 55(7), 1043–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Custodio, C., Mendes, D., & Metzger, D. (2025). The impact of the financial education of executives on the financial practices of medium and large enterprises. The Journal of Finance, 80(5), 2875–2920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (2000). The iron cage revisited: Isomorphism in organizational fields. Advances in Strategic Management, 48(2), 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dung, N. T. P., & Lien, N. T. H. (2024). Factors affecting the stages of management accounting evolution: The developing market research. Journal of Governance and Regulation, 13(2), 452–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, P., Brusca, I., & Fernandes, M. J. (2019). Implementing the international public sector accounting standards for consolidated financial statements: Facilitators, benefits and challenges. Public Money & Management, 39(3), 544–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossi, G., & Steccolini, I. (2015). Pursuing private or public accountability in the public sector? Applying IPSASs to define the reporting entity in municipal consolidation. International Journal of Public Administration, 38(4), 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, D. T., Armenakis, A. A., Feild, H. S., & Harris, S. G. (2007). Readiness for organizational change: The systematic development of a scale. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 43(2), 232–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyndman, N., & Connolly, C. (2011). Accruals accounting in the public sector: A road not always taken. Management Accounting Research, 22(1), 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICAEW. (2023). IFRS vs. IPSAS in public sector financial reporting: Part II measurement. Available online: https://www.icaew.com/technical/public-sector/public-sector-financial-reporting/financial-reporting-insights-listing/ifrs-vs-ipsas-2 (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- IPSASB. (2021). ED 77: Measurement [exposure draft]. Available online: https://www.ipsasb.org/publications/exposure-draft-ed-77-measurement (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- IPSASB. (2022). IPSAS 12: Inventories. International Public Sector Accounting Standards Board. [Google Scholar]

- IPSASB. (2023a). IPSAS 31: Intangible assets. International Public Sector Accounting Standards Board. [Google Scholar]

- IPSASB. (2023b). IPSAS 45: Property, plant and equipment. International Public Sector Accounting Standards Board. [Google Scholar]

- IPSASB. (2023c). IPSAS 46: Measurement. International Public Sector Accounting Standards Board. [Google Scholar]

- Lamm, K. W., Lamm, A. J., & Edgar, D. (2020). Scale development and validation: Methodology and recommendations. Journal of International Agricultural and Extension Education, 27(2), 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapsley, I. (2009). New public management: The cruellest invention of the human spirit? Abacus, 45(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maali, B. M., & Morshed, A. (2025). Impact of IPSAS adoption on governance and corruption: A comparative study of Southern Europe. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(2), 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Finance of Georgia. (2020). Order no. 108: On the approval of the instruction on accounting and financial reporting by budgetary organizations based on the International Public Sector Accounting Standards (IPSASs). Available online: https://mof.ge (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- Oulasvirta, L. (2014). Governmental financial accounting and European harmonisation: Case study of Finland. Accounting, Economics, and Law, 4(3), 237–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polzer, T., Grossi, G., & Reichard, C. (2021). Implementation of the international public sector accounting standards in Europe. Variations on a global theme. Accounting Forum, 46(1), 57–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudzioniene, K., & Juozapaviciute, T. (2014). Quality of financial reporting in public sector. Social Sciences, 82(4), 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabauri, L. (2018, June 2–3). Lease accounting: Specifics. 167th The IIER International Conference, Berlin, Germany. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/citations?view_op=view_citation&hl=en&user=mjrj6wsAAAAJ&citation_for_view=mjrj6wsAAAAJ:zYLM7Y9cAGgC (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Sabauri, L. (2024). Internal audit’s role in supporting sustainability reporting. International Journal of Sustainable Development & Planning, 19(5), 1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabauri, L., Vardiashvili, M., & Maisuradze, M. (2022). Methods for measurement of progress of performance obligation under IFRS 15. Ecoforum, 11(3), 29. [Google Scholar]

- Sabauri, L., Vardiashvili, M., & Maisuradze, M. (2023). On recognition of contract asset and contract liability in the financial statements. Ecoforum, XIX, 42–49. [Google Scholar]

- Samarghandi, H., Askarany, D., & Banitalebi Dehkordi, B. (2023). A hybrid method to predict human action actors in accounting information system. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 16(1), 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNCTAD. (2022). Report of the Intergovernmental Working Group of experts on international standards of accounting and reporting: Thirty-ninth session, Geneva. Available online: https://unctad.org (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- van Helden, J., & Uddin, S. N. (2016). Public sector management accounting in emerging economies: A literature review. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 41, 34–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardiashvili, M. (2018). Theoretical and practical aspects of impairment of non-cash-generating assets in the public sector entities, according to the international public sector accounting standard (IPSAS) 21. Ecoforum, 7(3), 830. [Google Scholar]

- Vardiashvili, M. (2024). Review of measurement-related changes in international public sector accounting standards (IPSAS). Economics and Business, 16(3), 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardiashvili, M. (2025). Measurement of non-financial assets at current operational value. Finance Accounting and Business Analysis, 7(1), 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. (2014). Financial management in the public sector: Tools, applications and cases (3rd ed.). Routledge. Available online: https://api.taylorfrancis.com/content/books/mono/download?identifierName=doi&identifierValue=10.4324/9781315704333&type=googlepdf (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- World Bank. (2025). Georgia public sector accounting assessment (PULSE report). Available online: https://cfrr.worldbank.org/publications/public-sector-accounting-assessment-pulse-report-georgia (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Zasadnyi, M., & Konovalenko, L. (2025). Implementation of international public sector accounting standards by developing countries. Economy and Society. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level of Education | Years of Experience | Current Position | |||

| Education | % | Years of Experience | % | Position | % |

| High School | 1 | 1–5 years | 6 | Certified Accountant | 65 |

| Vocational College (two-year program) | 12 | 6–10 years | 10 | Practicing Accountant | 33 |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 25 | 11–15 years | 22 | Trainee | 2 |

| Master’s Degree | 58 | 16–20 years | 25 | - | - |

| Doctoral Studies | 4 | Over 20 years | 37 | - | - |

| No. | Factor | χ2 | df | N | p | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | IPSAS Knowledge × Attitude | 28.74 | 4 | 990 | <0.001 | Knowledge increases readiness |

| 2 | Budgetary Constraints × Attitude | 16.58 | 2 | 400 | <0.001 | Lack of funds reduces readiness |

| 3 | Institutional Support × Attitude | 21.94 | 2 | 980 | <0.001 | Institutional support increases readiness |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sabauri, L.; Vardiashvili, M.; Maisuradze, M. Readiness and Perceptions of IPSAS 46 “Measurement” Implementation in Public Sector Entities: Evidence from Georgia. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2026, 19, 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm19010036

Sabauri L, Vardiashvili M, Maisuradze M. Readiness and Perceptions of IPSAS 46 “Measurement” Implementation in Public Sector Entities: Evidence from Georgia. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2026; 19(1):36. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm19010036

Chicago/Turabian StyleSabauri, Levan, Mariam Vardiashvili, and Marina Maisuradze. 2026. "Readiness and Perceptions of IPSAS 46 “Measurement” Implementation in Public Sector Entities: Evidence from Georgia" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 19, no. 1: 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm19010036

APA StyleSabauri, L., Vardiashvili, M., & Maisuradze, M. (2026). Readiness and Perceptions of IPSAS 46 “Measurement” Implementation in Public Sector Entities: Evidence from Georgia. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 19(1), 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm19010036