A Brain-Based Foundation for Momentum

Abstract

1. A Brain-Based Foundation for Momentum

2. Predictive Processing: A Brain-Based Foundation for Asset Pricing

2.1. The Default Perception in the Resource-Constrained Brain

2.2. Signal Processing in the Resource-Constrained Brain

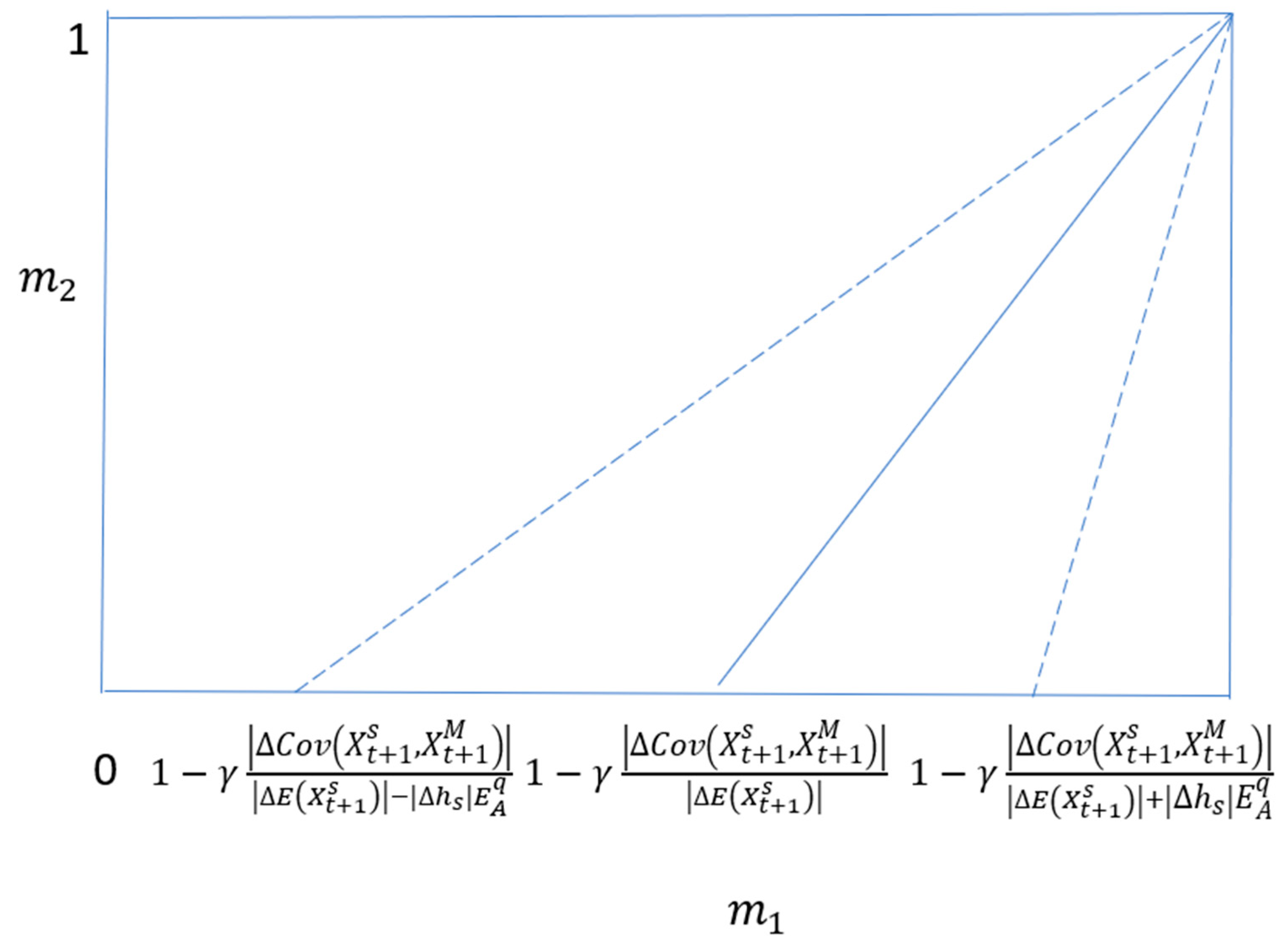

3. The Momentum Premium

Momentum Premium: Additional Insights and Empirical Evidence

4. Asymmetric Response to News

4.1. Response to Earnings-Specific News

4.2. Response to Risk-Specific News

4.3. Response to Earnings and Risk News

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | A large body of literature in brain sciences on how the brain is a prediction engine includes Nave et al. (2020), Clark (2013), Hohwy (2013), Bubic et al. (2010), among others. An accessible sample based on writings of prominent brain scientists includes Clark (2023), chapter 3 in Hawkins (2021), chapter 4 in Feldman (2021a), chapter 4 in Seth (2021), and chapters 4 and 5 in Goldstein (2020). Feldman (2021b) also provides a summary of the main ideas. |

| 2 | Ali et al. (2022) demonstrate that predictive processing emerges in an artificial neural network optimized to be energy efficient, indicating that such optimization may be why the brain implements predictive processing. |

| 3 | Instead of transmitting a large file, only the error signals are transmitted, with what is already known (default) at the receivers end used to reconstruct the file. Similarly, instead of storing all the neighboring frames in a large video file, a frame and its associated error signals are stored (see chapter 1 in Clark (2023)). |

| 4 | Doherty et al. (2021) present a review of the neuroscience evidence showing that the brain constructs value from key features in a process that involves the brain regions of the lateral orbital and medial prefrontal cortex. |

| 5 | |

| 6 | Such categorization is a critical part of the way the brain puts the world in order and has a dedicated neuronal mechanism in the brain (Lech et al., 2016). There is a significant body of literature in economics on categorization. See Mohlin (2014) for a discussion on optimal categorization. For an overview of a large body of literature, see Cohen and Lefebvre (2005) and Murphy (2002). Prominent economic applications of categorization include “coarse thinking” (Mullainathan et al., 2009) and “the economics of structured finance” where rating agencies categorize firms with respect to default risk (Coval & Jurek, 2009) among others. |

References

- Ali, A., Ahmad, N., de Groot, E., Johannes van Gerven, M. A., & Kietzmann, T. C. (2022). Predictive coding is a consequence of energy efficiency in recurrent neural networks. Patterns, 3(12), 100639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apps, M. A. J., & Tsakiris, M. (2014). The free-energy self: A predictive coding account of self-recognition. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Review, 41, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asness, C., & Moskowitz, L. (2013). Value and momentum everywhere. Journal of Finance, 68(3), 929–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avramov, D., Cheng, S., & Hameed, A. (2014). Time varying liquidity and momentum profits. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 51(6), 1897–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ba, C., Bohren, J. A., & Imas, A. (2025). Over-and underreaction to information (Revise-and-Resubmit). Quarterly Journal of Economics. Available online: https://cuiminba.com/working-papers/overreaction/ (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Bargh, J. A. (1994). The four horsemen of automaticity: Awareness, intention, efficiency, and control in social cognition. In R. S. Wyer Jr., & T. K. Srull (Eds.), Handbook of social cognition: Basic processes; applications (2nd ed., pp. 1–40). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Barroso, P., Detzel, A., & Maio, P. (2025). The volatility puzzle of the beta anomaly. Journal of Financial Economics, 165, 103994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, P., Orban, G., Lengyel, M., & Fiser, J. (2011). Spontaneous cortical activity reveals hallmarks of an optimal internal model of the environment. Science, 331(6013), 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordalo, P., Gennaioli, N., & Shleifer, A. (2022). Salience. Annual Review of Economics, 14, 521–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossaerts, P. (2009). What decision neuroscience teaches us about financial decision-making. Annual Review of Financial Economics, 1, 383–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubic, A., Von Cramon, D. Y., & Schubotz, R. I. (2010). Prediction, cognition and the brain. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 4, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchel, C., Geuter, S., Sprenger, C., & Eippert, F. (2014). Placebo analgesia: A predictive coding perspective. Neuron, 81(6), 1223–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, H. A., Kolari, J. W., & Sadaqat, M. (2021). Revisiting momentum profits in emerging markets. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 65, 101486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J., Giglio, S., & Polk, C. (2023). What drives booms and busts in value (NBER working paper No. 31859). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Chabot, B., Ghysels, E., & Jagannathan, R. (2009). Momentum cycles and limits to arbitrage: Evidence from Victorian era and post-depression US stock market (NBER Paper No. 15591). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Chan, W. S. (2003). Stock price reaction to news and no-news: Drift and reversal after headlines. Journal of Financial Economics, 70(2), 223–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A. (2013). Whatever next? Predictive brains, situated agents, and the future of cognitive science. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 36, 181–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, A. (2023). The experience machine: How our minds predict and shape reality (1st ed.). Allen Lane. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, H., & Lefebvre, C. (2005). Handbook of categorization in cognitive science. Elsevier Science. ISBN 978-0-08-044612-7. [Google Scholar]

- Coval, J. D., & Jurek, E. J. (2009). The economics of structured finance. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 23(1), 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, J. P., Rutishauser, U., & Iigaya, K. (2021). The hierarchical construction of value. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 41, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elk, M. (2021). A predictive processing framework of tool use. Cortex, 139, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engstrom, J., Bargman, J., Nilsson, D., Seppelt, B., Markkula, G., Piccinini, G. B., & Viktor, T. (2018). Great expectations: A predictive coding account of automobile driving. Theoretical Issues in Ergonomics Science, 19(2), 156–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, L. B. (2021a). Seven and a half lessons about the brain. Mariner Books. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, L. B. (2021b). Your brain predicts (almost) everything you do. Available online: https://www.mindful.org/your-brain-predicts-almost-everything-you-do/ (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Frazzini, A., & Pedersen, L. (2014). Betting against beta. Journal of Financial Economics, 114, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannikos, C., & Ji, X. (2007). Industry momentum at the end of the 20th century. International Journal of Business and Economics, 6, 29–46. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, B. (2020). The mind: Consciousness, prediction, and the brain. The MIT Press. ISBN-10 0262044064. [Google Scholar]

- Goyal, A., Jegadeesh, N., & Subrahmanyam, A. (2025). Empirical determinants of momentum: A perspective using international data. Review of Finance, 29(1), 241–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, J. D., & Fletcher, P. C. (2017). Predictive processing, source monitoring, and psychosis. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 13(13), 265–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, J. (2021). A thousand brains: A new theory of intelligence. Basic Books. ISBN-10 1541675819. [Google Scholar]

- Heston, S., Jones, C., Khorram, M., Li, S., & Mo, H. (2023). Option momentum. Journal of Finance, 78(6), 3141–3192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirshleifer, D., Lim, S. S., & Teoh, S. H. (2009). Driven to distraction: Extraneous events and underreaction to earnings news. Journal of Finance, 64(5), 2289–2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirshleifer, D., Lim, S. S., & Teoh, S. H. (2011). Limited investor attention and stock market misreactions to accounting information. Review of Asset Pricing Studies, 1(1), 35–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohwy, J. (2013). The predictive mind. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199682737. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, H., Lim, T., & Stein, C. (2000). Bad news travels slowly: Size, analyst coverage, and the probability of momentum strategies. Journal of Finance, 55, 265–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jegadeesh, N., & Titman, S. (1993). Returns to buying winners and selling losers: Implications for stock market efficiency. Journal of Finance, 48(1), 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D. (2012). Thinking fast and slow. Penguin Books Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, B. T., Moskowitz, T., & Pruitt, S. (2021). Understanding momentum and reversal. Journal of Financial Economics, 140(3), 726–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S., & Tang, J. (2025). Extreme categories and overreaction to news. Review of Economic Studies, rdaf037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lech, R., Güntürkün, O., & Suchan, B. (2016). An interplay of fusiform gyrus and hippocampus enables prototype- and exemplar-based category learning. Behavioural Brain Research, 311, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leseur, M. (2016). Analysis of the causes of the momentum effect and the implications for the efficient market hypothesis [Master’s thesis, Université de Liège]. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y., Nekrasov, A., & Teoh, S. H. (2020). Opportunity knocks but once: Delayed disclosure of financial items in earnings announcements and neglect of earnings news. Review of Accounting Studies, 25(1), 159–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z., Wen, F., & Huang, Z. (2023). Asymmetric response to earnings news across different sentiment states: The role of cognitive dissonance. Journal of Corporate Finance, 78, 102343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, D., Polk, C., & Skouras, S. (2019). A tug of war: Overnight versus intraday expected returns. Journal of Financial Economics, 134(1), 192–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackowiak, B., Matejka, F., & Wiederholt, M. (2023). Rational inattention: A review. Journal of Economic Literature, 62, 226–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohlin, E. (2014). Optimal categorization. Journal of Economic Theory, 152, 356–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moskowitz, T. (2010). Explanations for the momentum premium. In AQR capital management. University of Chicago Booth School of Business. [Google Scholar]

- Moskowitz, T., & Grinblatt, M. (1999). Do industries explain momentum? Journal of Finance, 54, 1249–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullainathan, S., Schwartzstein, J., & Shleifer, A. (2009). Coarse thinking and persuasion. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123(2), 577–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, G. L. (2002). The big book of concepts. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nagel, S., & Singleton, K. J. (2011). Estimation and evaluation of conditional asset pricing models. Journal of Finance, 66, 873–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanamoorthy, G., & He, S. (2020). Earning acceleration and stock returns. Journal of Accounting & Economics, 69(1), 101238. [Google Scholar]

- Nave, K., Deane, G., Miller, M., & Clark, A. (2020). Wilding the predictive brain. Wiley Interdisciplinary Review of Cognitive Science, 11(6), E1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekrasov, A., Teah, S., & Wu, S. (2023). Limited attention and financial decision making. In G. Hillary, & D. McLean (Eds.), Handbook of financial decision making. Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Novy-Marx, R. (2015). Fundamentally, momentum is fundamental momentum (NBER paper No. 20984). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Raichle, M. E. (2010). Two views of brain function. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 14(4), 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renevier, S. (2024). Sharpen your edge: A simple guide to sector momentum investing. Available online: https://finimize.com/content/sharpen-your-edge-a-simple-guide-to-sector-momentum-investing (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Seth, A. (2021). Being you: A new science of consciousness. Dutton Books. [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqi, H. (2024a). Information processing in the brain and financial innovations. Journal of Behavioral Finance, 25(4), 410–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqi, H. (2024b). Strict certainty preference in the predictive brain: A new perspective on financial innovations and their role in the real economy. Annals of Finance, 20, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqi, H. (2025a). Asset pricing with finite attention. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5213132 (accessed on 31 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Siddiqi, H. (2025b). Option pricing with rational inattention. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5172077 (accessed on 10 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Siddiqi, H., & Murphy, A. (2023). The resource-constrained brain: A new perspective on the equity premium puzzle. Journal of Behavioral Finance, 24(3), 315–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, C. A. (2010). Rational inattention and monetary economics. In B. M. Friedman, & M. Woodford (Eds.), Handbook of monetary economics (Vol. 3, pp. 155–181). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Veldkamp, L. (2011). Information choice in macroeconomics and finance. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wiederholt, M. (2010). Rational inattention. In The new palgrave dictionary of economics (Online ed.). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Y. (2015). Market-wide attention, trading, and stock returns. Journal of Financial Economics, 116(3), 548–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Siddiqi, H. A Brain-Based Foundation for Momentum. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2026, 19, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm19010003

Siddiqi H. A Brain-Based Foundation for Momentum. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2026; 19(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm19010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleSiddiqi, Hammad. 2026. "A Brain-Based Foundation for Momentum" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 19, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm19010003

APA StyleSiddiqi, H. (2026). A Brain-Based Foundation for Momentum. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 19(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm19010003