1. Introduction

The independence of the Federal Reserve System (the Fed) is under attack. The Fed’s defense is at best anemic. To defend its independence, the Fed should undertake reforms that would make it more transparent and accountable. It should start by communicating the nature of the monetary policy regime using a simple conceptual framework. In doing so, the FOMC (Federal Open Market Committee) would answer basic questions about what macroeconomic variables it controls and how it exercises the required control over the behavior of households and firms. Importantly, what limitations are imposed on that control?

The FOMC routinely announces allegiance to the dual mandate of stable prices and maximum employment. Achievement of those objectives requires coordinating the behavior of households and firms in a way that makes them behave collectively so as to achieve those goals. A simple conceptual framework would elucidate the nature of the transmission mechanism (the structure of the economy) that translates the FOMC’s meeting-by-meeting announcement of the funds rate into the required collective behavior of the agents in the economy. Households and firms base their behavior on forecasts of the future. To shape those forecasts in a way conformable with achievement of the FOMC’s objectives, the FOMC must behave in a consistent way in response to new information on the behavior of the economy. It follows that the conceptual framework must contain a reaction function (a rule) embedded in a model.

With the phrase “leaning against the wind” (LAW), FOMC chairman William McChesney Martin characterized the underlying consistency in policy developed after the 1951 Treasury–Fed Accord. With LAW, the FOMC raises the funds rate when the economy is growing unsustainably fast (the economy’s rate of resource utilization is rising in a sustained way, for example, the unemployment rate is declining), and conversely for sustained weakness. However, there are two basic variations in LAW reflecting primarily whether the rule incorporates preemptive changes in the funds rate to prevent inflation from diverging from price stability. Unfortunately, the FOMC’s use of the language of discretion crowds out any discussion of the consistency in its policy. The Fed’s defense of its independence is little more than the statement “trust me.”

Section 2 reviews the need to examine the appropriate nature of central bank independence in a democracy.

Section 3 argues that in its public communication, the Fed should move beyond forward guidance about the likely path of the funds rate and articulate the nature of the monetary policy regime it has created using a simple conceptual model.

Section 3 argues that the long-term consistency provided by a rule is especially important in times of elevated uncertainty about the behavior of the economy.

Section 5 illustrates the consensus within the economics profession that a model imposing consistency on monetary policy actions over time is required for understanding how monetary policy achieves its desired objectives.

Section 6 illustrates the incompleteness of FOMC communication when based solely on the judgment of policymakers about the near-term evolution of the economy.

In a Brookings paper, Ben Bernanke highlighted the uninformative nature of the reasons the FOMC uses to explain the funds rate decisions made at FOMC meetings.

Section 7 elaborates the proposal he offers to correct this deficiency.

Section 8 exposits the monetary policy regime using a model that assumes inflation is a monetary phenomenon. In doing so, the exposition offers an example showing that the FOMC could use a model and a rule to communicate the nature of the monetary policy regime. A presumed continual evolution of the structure of the economy in no way justifies the use of the language of discretion by the FOMC.

Section 9 speculates on the political economy reasons for why the Fed operates without a conceptual framework that explains how monetary policy affects the economy in a way that attains its objectives. One reason that the current monetary policy regime is fragile is that policymakers have never had to make explicit their understanding of the general structure of the economy (a model) and, given that understanding, examine their own views concerning how their actions play out within the broad economy.

Section 10 argues that revival of the monetarist-Keynesian debate of the 1970s is desirable to arrive at a consensus over the pertinent issues in the choice of a model. The debate needs to start by asking whether inflation is a monetary or a nonmonetary phenomenon. For that debate to be fruitful, it will be necessary to revise the monetarist model to make it relevant to current central bank practice.

Section 11 examines whether the behavior of the monetary aggregate M2 is consistent with inflation being a monetary phenomenon and with the need for monetary control to achieve price stability.

Section 12 discusses whether the reinvention of the Fed as a combination traditional central bank and housing GSE, which started with the Bernanke FOMC, was a desirable development.

Section 13 argues that the best way to defend Fed independence is through a rule rather than through the current practice in which the FOMC uses the language of discretion to rationalize its behavior meeting by meeting.

Section 14 discusses how the Fed could organize a genuine internal debate over the optimal rule.

2. The Fed Should Explain the Appropriate Role of Independence in a Democracy

Bessent (

2025), Treasury Secretary, criticized the Fed:

The Fed’s new operating model is effectively a gain-of-function monetary policy experiment. … The Fed must change course. Its standard tool kit has become too complex to manage, with uncertain theoretical underpinnings. Simple and measurable tools, aimed at a narrow mandate, are the clearest way to deliver better outcomes and safeguard central-bank independence over time. … Successive interventions during and after the financial crisis of 2008 created what amounted to a de facto backstop for asset owners. … This harmful cycle concentrated national wealth among those who already owned assets. … At the heart of independence lies credibility and political legitimacy. Both have been jeopardized by the Fed’s expansion beyond its mandate. Heavy intervention has produced severe distributional outcomes, undermined credibility and threatened independence. … There must also be an honest, independent, nonpartisan review of the entire institution, including monetary policy, regulation, communications, staffing and research.

Bessent’s main criticism concerns what is more commonly referred to as “mission creep.” The specific reference is to the undesirable distributional outcomes of bank bailouts—a privilege not accorded to regular corporations. More generally, as exemplified by the payment of interest on reserves and a gigantic increase in the size of the Fed’s portfolio, the nature of the monetary policy regime and the implementation of monetary policy have become so complicated and opaque that only a small number of devoted Fed watchers can follow and assess the Fed’s actions. Most significant, should not the FOMC take seriously Bessent’s call for “an honest, independent, nonpartisan review” and act preemptively to undertake such a review on its own? A forthright review acknowledging cons as well as pros would go a long way to convince the public and politicians that the Fed is not just a government bureaucracy that grows over time and always defends the status quo. The Fed would submit its review for serious outside discussion with academic economists.

Section 2A “Monetary policy objectives” of the Federal Reserve Act states that “The Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System and the Federal Open Market Committee shall maintain long run growth of the monetary and credit aggregates commensurate with the economy’s long run potential to increase production, so as to promote effectively the goals of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates.” Each of these three objectives raises issues of implementation in a democracy. Specifically, should they not all involve some participation by outside groups, especially elected politicians?

Consider “maximum employment” first. In 2020, pursuant to the revision of its consensus statement (Review of Monetary Policy Strategy, Tools, and Communications), the Fed engaged with community groups in a series of meetings entitled “Fed Listens.” As a result of this engagement, the FOMC adopted an “inclusive definition” of maximum employment.

Powell (

2020) stated: “Our revised statement emphasizes that maximum employment is a broad-based and inclusive goal. This change reflects our appreciation for the benefits of a strong labor market, particularly for many in low- and moderate-income communities.” Governor

Brainard (

2020) said: “The broad-based and inclusive definition of maximum employment calls for a more comprehensive assessment of areas of slack in the labor market, such as the disparities in employment outcomes I discussed earlier [for Black and Hispanic workers].

Should not the FOMC institutionalize these procedures in an ongoing determination of how to define the maximum employment objective?

What about the “stable prices” objective? Since 2021Q1, inflation (year over year quarterly changes in the personal consumption expenditures chain-type price index) has exceeded the FOMC’s 2% target. From 2023Q4 through 2025Q3, the series has come in close to 3 percent. Given widespread public concern about inflation, should not the FOMC incorporate public input in how close to stay to the 2% target? The final part of the mandate is “moderate long-term interest rates.” Should not the FOMC heed the appeal of the administration to maintain low interest rates to lessen the cost of financing the government deficit?

3. The Fed Should Articulate the Nature of the Monetary Policy Regime It Has Created

Federal Reserve policymakers confine their communication with the public to the practicalities of the implementation of monetary policy. They do so while leaving unarticulated the nature of the monetary policy regime itself, which is the causal framework that endows them with the ability to achieve the objectives of the dual mandate—stable prices and maximum employment. Communication about the implementation of policy is atheoretical. Communication about the nature of the monetary policy regime requires a model—a conceptual framework that explains what macroeconomic variables the FOMC controls, how it exercises that control, and what the limitations are to that control.

Monetary policymakers routinely proclaim their power to ensure maximum employment and stable prices. Such power must endow them with the ability to control the collective spending of households and the collective price setting and hiring of firms. But how do policymakers explain how such extraordinary power comes from setting the federal funds rate—a short-term interest rate?

The Fed does not operate in a wartime command and control economy. How then does it achieve the objectives of the dual mandate to which it professes allegiance? To achieve its objective of price stability, it must coordinate the way that firms set relative prices in dollars so that collectively there is no change in the average of the dollar prices. In a market economy, price stability does not mean freezing individual dollar prices. To achieve its objective of maximum employment, it must influence the hiring and firing decisions of firms so that collectively net hiring increases in line with growth in the available labor force. In a market economy, full employment does not mean that every firm increases its labor force in line with changes in the working-age population.

The fact that the Fed does not explain the nature of its powers raises many questions. Should not such power be constrained by explicit rules to prevent its abuse? Is not making explicit the nature of that power necessary for the accountability required in a democracy? Does “independence” require making the Fed into a fourth branch of government? Should not the power of the Fed be subject to the checks and balances of a constitutional democracy? These issues are especially pressing at present. The greater the power exercised by the FOMC, the greater the incentive to take control of that power by parties outside of the Fed. The failure of the Fed to communicate in terms of a model, which explains how the price system transmits its actions to the behavior of the economy, leaves it without an explanation of what the limits are to its ability to lower interest rates in order to lower the cost of government debt service or to achieve a socially desirable low rate of unemployment.

4. Uncertainty Increases the Need for a Long-Run Strategy (A Rule)

As exemplified by uncertainty over tariffs, the difficult environment in which the FOMC operates increases the difficulty of implementing a stabilizing monetary policy. At the same time, that uncertainty brings out the importance of a rules-based monetary policy, which imposes consistency over time. The heightened uncertainty means that hindsight could indicate the desirability of a different policy than the one actually adopted based on the FOMC’s contemporaneous best guess about the evolution of the economy. A stabilizing monetary policy must therefore assure the public that long-run stability, nominal and real, will prevail. For that to happen, the public needs the confidence that comes from knowing that the FOMC possesses an underlying strategy that has worked in the past to maintain economic stability. The FOMC should articulate that strategy and defend it based on a model that brings coherence to historical experience.

Similarly, the uncertain environment that began with the Trump presidency illustrates the misleading character of the Fed’s argument for discretion. (For the Board’s defense of discretion, see

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 1994/2018). The standard Fed argument for discretion is that uncertainty about the future means that monetary policy cannot be subject to a “mechanical” rule. The appellation “mechanical” is misleading. Implementation of any rule entails judgment about the near-term evolution of the economy. That fact does not eliminate the need for consistency over time. Consider an example relevant in 2026. The government is running an unsustainable and historically large deficit at a time of prosperity. A fractured political system appears to make the required return to fiscal responsibility depend upon the occurrence of a financial crisis that forces some kind of action because of a surge in bond rates and a depreciation of the dollar. In this situation, a rule that ensures long-run price stability and that prevents a rise in inflationary expectations is critical.

The confusion on the part of the FOMC about the desirability of a rule appears to come from a failure to appreciate the role of a reaction function in a model. A reaction function communicates to the public the consistency in how the FOMC responds to incoming new information and is therefore the foundation for shaping the expectations of the public in a way consistent with a stabilizing monetary policy. The following quotations illustrate the need to impose structure on monetary policy through the use of an explicit model (Tobin) with a reaction function (Friedman) so as to ensure that the public forms its expectations in a stabilizing way (

Woodford, 2005).

5. Why Impose Consistency on Monetary Policy Through the Use of a Model?

Academic economists of all persuasions have expressed frustration over FOMC silence on how its policy actions transmit through the structure of the economy in a way that it achieves its objectives. Tobin (1977, as cited in

Lombra & Moran, 1980) wrote:

There is really no substitute for making policy backwards, from the desired feasible paths of the objective variables that really matter to the mixture of policy instruments that can bring them about. … The procedure requires a model—there is no getting away from that. Models are highly imperfect, but they are indispensable. The model used for policymaking need not be any of the well-known forecasting models. It should represent the policymakers’ beliefs about the way the world works, and it should be explicit. Any policymaker or advisor who thinks he is not using a model is kidding both himself and us. He would be well advised to make explicit both his objectives for the economy and the model that expresses his view of the links of the economic variables of ultimate social concern to his policy instruments.

As Tobin explained, an explicit strategy must detail the “desired feasible paths of the objective variables that really matter” to the policymaker and “the model that expresses his view of the links of the economic variables of ultimate social concern to his policy instruments.” In the same spirit,

Friedman (

1988) wrote:

Every now and then a reporter asks my opinion about “current monetary policy.” My standard reply has become that I would be glad to answer if he would first tell me what “current monetary policy” is. I know, or can find out, what monetary actions have been: open-market purchases and sales and discount rates at Federal Reserve Banks. I know also the federal funds rate and rates of growth of various monetary aggregates that have accompanied these actions. What I do not know is the policy that produced these actions. The closest I can come to an official specification of current monetary policy is that it is to take those actions that the monetary authorities, in light of all evidence available, judge will best promote price stability and full employment-i.e., to do the right thing at the right time. But that surely is not a “policy.” It is simply an expression of good intentions and an injunction to “trust us.”

Woodford (

2005, pp. 401, 436–437) expressed the general point:

Because the key decision-makers in an economy are forward-looking, central banks affect the economy as much through their influence on expectations as through any direct, mechanical effects of central bank trading in the market for overnight cash. As a consequence, there is good reason for a central bank to commit itself to a systematic approach to policy, that not only provides an explicit framework for decision making within the bank, but that is also used to explain the bank’s decisions to the public.

The signals that have been given thus far through the post-meeting [FOMC] statements all attempt to say something about the likely path of the funds rate for the next several months. … They do not speak of the way in which future policy should be contingent on circumstances that are not already evident. If the statements are interpreted as commitments to particular non-state-contingent paths for the funds rate … then they are likely to constrain policy in ways that are not fully ideal. For while an optimal policy commitment will generally imply that policy should be history-dependent…, it will also generally imply the policy should be state contingent as well. (italics in original)

Understanding how monetary policy achieves its objectives requires a model and a strategy that imposes consistency on FOMC behavior over time. That is, it requires a model that summarizes in a general way how the price system and expectations coordinate the behavior of firms and households and a reaction function that explains how the FOMC responds to new information on the economy.

6. The Incompleteness of the FOMC’s Public Communication

Before illustrating how to give content to the normative advice offered in

Section 4, it will be useful to address the criticisms that the Fed will raise. Inevitably, the Fed will object that it already fully characterizes the monetary policy regime that it has devised. It has one so, it will be claimed, in the consensus statement (Review of Monetary Policy Strategy, Tools, and Communications) and in the speeches regularly offered by the FOMC chair.

An example of Fed communication can be found in the speech of FOMC chair Jay Powell at the Jackson Hole Conference in August 2025. The spirit of the speech is that at each meeting, the FOMC evaluates the state of the economy and decides on a balance of risks. That is, which part of the dual mandate (maximum employment or stable prices) is more at risk and then acts to mitigate that risk. What comes across is the focus on short-run forecasting with no attempt to use an analytical framework that remains in place over time and that allows for rectification of the ex post errors in reading the economy that inevitably arise.

Powell (

2025, p. 5) said:

Putting the pieces together [evaluating the state of the economy], what are the implications for monetary policy? In the near term, risks to inflation are tilted to the upside, and risks to employment to the downside—a challenging situation. When our goals are in tension like this, our framework calls for us to balance both sides of our dual mandate. Our policy rate is now 100 basis points closer to neutral than it was a year ago, and the stability of the unemployment rate and other labor market measures allows us to proceed carefully as we consider changes to our policy stance. Nonetheless, with policy in restrictive territory, the baseline outlook and the shifting balance of risks may warrant adjusting our policy stance. Monetary policy is not on a preset course. FOMC members will make these decisions, based solely on their assessment of the data and its implications for the economic outlook and the balance of risks. We will never deviate from that approach.

As of August 2025, for example, Powell judged that although the risks were roughly balanced, the risk to the employment mandate was more pressing. Financial markets assumed that the FOMC would lower the funds rate at the September meeting.

The spirit of Powell’s speech is that instability arises routinely in the private sector.

Powell (

2025, p. 6) referred to a number of such episodes of instability confronting the FOMC. Moreover, the structure of the economy evolves:

In approaching this year’s review, a key objective has been to make sure that our framework is suitable across a broad range of economic conditions. At the same time, the framework needs to evolve with changes in the structure of the economy and our understanding of those changes. The Great Depression presented different challenges from those of the Great Inflation and the Great Moderation, which in turn are different from the ones we face today.

In countering the instability of such episodes as well as the evolving contemporaneous structure of the economy, the FOMC needs a full range of tools. In reference to the August 2025 revision to the FOMC’s consensus statement,

Powell (

2025, p. 9) said: “The revised statement reiterates that the Committee is prepared to use its full range of tools to achieve its maximum-employment and price-stability goals.”

The expectations of the public are critical.

Powell (

2025, p. 10) said:

Well-anchored inflation expectations were critical to our success in bringing down inflation without a sharp increase in unemployment. Anchored expectations promote the return of inflation to target when adverse shocks drive inflation higher, and limit the risk of deflation when the economy weakens. Further, they allow monetary policy to support maximum employment in economic downturns without compromising price stability.

The speech raises numerous questions. In excerpt number one (“Putting the pieces together. …”), Powell implicitly assumes that macroeconomic instability arises in the private sector. The FOMC goes meeting by meeting, as expressed in the term “data dependent,” and observes what shocks are hitting the economy. An analogy would be that monetary policy functions as an iron dome defense mechanism for the economy. The FOMC watches for incoming missiles (shocks to the economy) and counters them with an offsetting force, that is, movements in the funds rate away from its prevailing value in a way that depends upon which of the two goals of the dual mandate are more affected.

Powell never considers the alternative that instability arises from monetary instability produced by the Fed. For example, in the 2008–2009 Great Recession, why did disinflation accompany a rise in unemployment? That combination is a sign of contractionary monetary policy. In the recent Great Inflation of 2021–2022, why did a high rate of money growth accompany the inflation? If Powell’s characterization of the FOMC as making individual policy actions at each meeting based on the contemporaneous state of the economy is correct, he should explain how the FOMC has solved the issue of long and variable lags raised by Milton Friedman. Has Powell merely made a statement of good intentions without providing a road map for how individual policy actions work to affect the behavior of the economy?

In excerpt number two, Powell asserts that the FOMC follows the evolving “structure of the economy,” but then nowhere explains where one can find documentation of the FOMC’s characterization of that structure not only at present but also in the past.

Powell’s (

2025, p. 5) statement that “Our policy rate is now 100 basis points closer to neutral than it was a year ago. …” must be based on such knowledge.

In excerpt number three, Powell stresses the importance of “well-anchored inflation expectations.” For example, to be more specific than Powell, in lowering the funds rate to counter recession, stability in expected inflation requires the belief by markets that the FOMC will raise the funds rate in the future when necessary to maintain price stability. For the FOMC to predict the corresponding response of the entire yield curve to current policy actions, it must possess an understanding of what markets believe about its future behavior. The FOMC must therefore impose consistency on its behavior over time. The FOMC must operate with a reaction function (rule) that imposes consistency over time on meeting-by-meeting funds rate changes in response to the arrival of new information on the economy. However, Powell never mentions the need for a rule to impose that consistency. While it is true that the FOMC has an inflation target of two percent, nothing in FOMC procedures imposes discipline on individual FOMC meetings to ensure its achievement over time.

7. Elaborating on the Bernanke Proposal to Clarify FOMC Communication

Former FOMC chairman Ben Bernanke highlighted the uninformativeness of the reasons the FOMC gives for its policy actions.

1 Bernanke (

2025) wrote: “The Fed differs from virtually all peer central banks in offering limited context and explanation of the policy decision at the time of the policy announcement, when attention to monetary policy is greatest.” He recommended that fund rate changes be accompanied by a “Review and analysis of recent economic and financial developments, Special topics and deep dives on relevant issues, and a macro forecast, including a transparent discussion and explicit assumptions.”

A comprehensive, internally consistent forecast can be used to identify the key factors driving the outlook (and changes in the outlook). Better communication. A fully articulated forecast allows for more quantitative communication while providing a baseline for creating alternative scenarios. Alternative scenarios facilitate communication that emphasizes the inherent uncertainty about the outlook and provide important information about the central bank’s policy reaction function.

Bernanke pointed out the deficiencies in the FOMC’s Summary of Economic Projections (SEP) and the dot plot. “They have significant drawbacks relative to a transparent, internally consistent forecast.” In particular, the dot plot “cannot accommodate state contingent guidance (or no guidance). Projections are not transparent and offer no rationale or analysis.”

Bernanke (

2025) argued for the inclusion of “staff forecasts of key macro variables, with discussion of key driving factors and underlying economic assumptions.” He recommended that they be “Distributed with [the] Tealbook.” The Tealbook is the document that contains the forecasts of the economy provided by Board of Governors’ staff prior to FOMC meetings.

Especially notable is Bernanke’s proposal to publish the Tealbook as background for the chairman’s post-meeting press conferences. However, in its current format, the Tealbook offers only a judgmental forecast. As a result, the relationship between the funds rate forecast contained in the Tealbook and its forecast of the economy is unclear. The argument made here is that the FOMC should tell the Board staff to organize the Tealbook forecast around a policy rule. The FOMC would then use the Tealbook to organize its own debate. An explicit policy rule highlighting the consistency in policy over time would eliminate the opacity that now enshrouds FOMC policy actions. The August 2011 Tealbook (

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 2011) contained a standard list of alternative rules from which the FOMC can choose.

At the post-FOMC meeting press conference, the chairman should offer an FOMC consensus SEP. There would be a single Committee forecast instead of the present forecasts of unidentified individual FOMC participants, with the categories of forecasts not identified with the author. The forecast should be for the following quarter and for the next four quarters to make them more relevant to the current policy decision. At the press conference, the chairman would recognize the difficulty in making forecasts and also the volatility of the monthly data, such as the payroll employment numbers. He can explain that short-term reversals of changes in the funds should occur occasionally. A rule would clarify that the reason is not due to political pressures, a point difficult to make given the language of discretion.

The press would have both the Tealbook forecast and the policy rule that organizes its forecast. The chairman would reference differences between the FOMC consensus forecast and the Board staff Tealbook forecast. Those differences would be of two kinds. The FOMC could have decided to depart from the policy rule in the Tealbook. Alternatively, the FOMC could have modified the Tealbook forecast of the economy. The public would then experience a serious debate over monetary policy because newspapers would start sending reporters with a background in economics to the press conferences. In addition, the FOMC should publish the transcripts of FOMC meetings within two months of the meeting. The public would then be assured that FOMC participants have the depth of knowledge required to make monetary policy. In the context of the inflation that accompanied the pandemic monetary policy,

Eggertsson and Kohn (

2023, p. 32) made this point.

[There were] two sources of inflationary bias in the framework: average inflation targeting that made up for undershoots of the target but not overshoots; and only weighting employment below its maximum level while putting no weight in policy on employment above its estimated maximum. … Putting no weight on the labor market overshooting its maximum level rules out policy action to preempt emerging inflation pressure generated by a labor market if inflation is at or below target. The strategy of preemption has been an essential part of how the Federal Reserve has operated over the past decades and is arguably one of the reasons for its success in maintaining inflation within a relatively narrow band.

They ended their critique by questioning whether the adoption of flexible-average-inflation targeting (FAIT) was preceded by a full and deep debate within the FOMC.

The years 2021 and early 2022 were extraordinarily difficult times for policymaking in which the path forward to accomplishing the Federal Reserve’s dual mandate was not clear and subject to different judgments. Yet no FOMC voters dissented between September 2020 and June 2022, raising questions about whether Committee discussions and decisions were being sufficiently challenged by diverse viewpoints. … The FOMC has had a very consensus-driven decision process. The Committee should ask itself whether different aspects of its decisions and decision making are allowing sufficient scope for effective challenges to the majority view. (underlining in the original).

8. Expositing the Monetary Policy Regime with a Model

The New Keynesian (NK) model is the standard model of the economy. The choice of what version to use depends upon the choice of whether inflation is a monetary or a nonmonetary phenomenon.

Goodfriend and King (

1997) exposit the former monetarist version. In their version, price stability is the optimal policy. Such a policy turns over the determination of real variables (output and employment) to the real business cycle core of the economy. The assumption that the price system works well to maintain full employment given price stability implies that the FOMC should prioritize its price stability mandate. In contrast,

Blanchard and Gali (

2007) defend the latter Keynesian version. They attribute volatility in inflation to markup shocks and conclude that a policy of price stability would require undesirable socially high rates of unemployment. They invented the term “divine coincidence” to characterize the

Goodfriend and King (

1997) policy of price stability as optimal.

Barsky et al. (

2014) exposited the version of the NK model in which price stability is optimal. It can be summarized in two equations. A forward-looking Phillips curve makes inflation a function of expected inflation and markup shocks. A dynamic Euler equation makes the real rate of interest depend upon a constant term expressing households’ rate of time preference and expected future output growth. If households expect higher future output growth, they will also expect higher future consumption. They then have an increased incentive to transfer income from the future to the present to smooth consumption intertemporally. Consequently, a higher real interest rate is required to maintain equality between contemporaneous real aggregate demand and potential real output.

One can re-express the Euler equation by taking the difference between the equation and actual values and then solving forward. The result is to express the output gap, the difference between actual output and its natural value, as the sum of contemporaneous and future gaps between the real rate of interest and its natural rate counterpart (The natural value obtains with complete price flexibility). Using the forward-looking Phillips curve and this version of the equation of the output gap, one can explain the rule that provides for price stability using the exposition of

Aoki (

2001) of the NK model with a sticky-price and a flexible-price sector.

Firms in the sticky-price sector set dollar prices for multiple periods, while firms in the flexible-price sector set prices each period in auction markets. Because inflation distorts the allocation of resources only for firms in the sticky-price sector, monetary policy should stabilize sticky-price (underlying) inflation while allowing flexible-price inflation to pass through to headline inflation. (Markup shocks affect the price level. However, given the expectation of price stability, they wash out because of their transitory nature.) A credible rule causes firms in the sticky-price sector to set prices based on the assumption of price stability. Monetary policy can then be implemented by turning over the determination of real variables to the unfettered operation of the price system. It does so through operating procedures that cause the funds rate to track the natural rate of interest in the current period and in future periods.

What rule tracks the natural rate of interest? A first-difference Taylor does so as estimated by

Orphanides (

2003) and

Orphanides and van Norden (

2002).

2 Note that with a first-difference rule, monetary policy stabilizes the economy’s rate of resource utilization. In particular, policy aims for stability in the unemployment rate rather than for an unemployment rate associated with a given amount of slack in the economy. The price system is then free to determine the level of real variables like employment and output. As shown by

Orphanides (

2023/2024), the discipline of monetary policy with an objective of price stability is that at each meeting, the FOMC’s forecast of inflation must equal the forecast of potential real output growth. As Orphanides shows, starting in the early 1990s, when this discipline was observed, inflation is stable at a low rate. The most recent failure of the FOMC to observe this discipline occurred with the 2021–2022 inflation.

The nature of the expectations shaped by the rule is what causes the stabilizing properties of the price system to work. Consider the case in which the FOMC determines that the economy is growing at an unsustainable rate, with the unemployment rate declining persistently. The FOMC will begin a succession of measured fund rate increases, typically, 25 basis points. However, markets in setting the behavior of the yield curve are under no such constraint given by these measured changes in the funds rate. They understand that the objective of monetary policy is to stabilize the economy’s rate of resource utilization. With that North Star, the yield curve moves continually as new information about the economy arrives to keep the yield curve aligned with its “natural level,” which keeps output fluctuating around potential real output.

With these price-stability procedures, the FOMC is controlling a nominal variable, the price level, rather than a real variable such as slack in the economy, expressed, for example, as the difference between the unemployment rate and a NAIRU value, which presumably measures full employment. To explain how these procedures provide for monetary control without the need for targets for money, note that they maintain the expectation of price stability and maintain real output at its full-employment level. These conditions both discipline the demand for money by the public and the supply of money by banks.

Given the rule, the demand for money grows in a way consistent with the expectation of underlying price stability (stability in sticky-price inflation) and with real output growing around potential real output. Banks accommodate that demand as a consequence of the central bank’s interest rate target, which determines banks’ marginal cost of funds. The FOMC’s Open Market Desk supplies whatever reserves banks demand at that interest rate. Also, with the funds rate equal to the natural rate of interest, there is no excess supply or demand for bonds in the bond market requiring monetization (bond purchases by the Desk) or extinguishing (bond sales by the Desk), respectively. No force causes an expansion or contraction of bank deposits (money) inconsistent with price stability.

3 9. Why Does the FOMC Chair Favor the Language of Discretion?

When this author became an economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond in 1975, he was struck by the fact that FOMC decision-making occurred without an explicit analytical framework relating FOMC actions to the desired behavior of macroeconomic variables. Al Burger, economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, offered an explanation to the author. He said that the FOMC chair wants to speak for the Committee and speaking for it requires a consensus. The chair finds it easier to gain consensus on individual policy actions meeting by meeting than to find consensus over a model of the economy relevant for understanding how monetary policy achieves its objectives.

The author’s colleague at the Richmond Fed, Marvin Goodfriend, expanded on the explanation. He noted that populist congressmen do not understand monetary economics and monetary policy, but they do understand a “chicken fight.” Populist congressmen attacking the Fed would call FOMC dissenters to testify to defend their case against increases in the funds rate (controlling inflation “on the backs of workers”). Moreover, organizing FOMC discussion around achieving a consensus over near-term forecasts of the economy and then making a funds rate decision based on the priority to assign to price stability or maximum employment allows the chair to use the language of discretion in defending that decision.

Also, a discipline imposed by an explicit rule would be seen by FOMC chairs as diminishing their dominant influence on the implicit strategy of monetary policy. FOMC meetings are organized around two “go-arounds.” In the first go-around, following staff presentations on the state of the economy, FOMC participants provide their own summaries of the state of the economy. After a break during which the FOMC chair and FOMC secretary can discuss how to modify the language of the Directive to achieve a consensus, the second go-around starts with a staff presentation of the alternatives for the choice of the funds rate. FOMC participants then state their preferences and there is a discussion led by the chair. FOMC chairs are the dominant players in the determination of monetary policy because of the influence they exert over the pattern of funds rate changes over time. There is a natural deference to FOMC chairs in this respect because of the recognition of the responsibility they carry for maintaining Fed independence.

The language of discretion allows FOMC communication to concentrate on the implementation of monetary policy embedded in a discussion of near-term forecasts of the evolution of the economy. This communication appears in the FOMC chair’s post-meeting press conference. The FOMC observes the evolution of the economy and then moves the funds rate away from its prevailing value in a commonsense way, depending upon whether the price stability or the maximum employment objective of the dual mandate is of more concern. The press naturally highlights this reading of the economy and the tweaks offered by FOMC participants. Only Fed watchers who follow the economy continuously possess the expertise required to challenge FOMC decisions. The spirit of the policy process is “Tell us what the economy will be doing next period, and we will do the right thing.”

10. Reviving the Monetarist-Keynesian Debate

The encyclopedic reading of the economy by FOMC participants conveys the impression that the FOMC is stabilizing the economy in fulfilling the dual mandate. Surely, given such a comprehensive knowledge of the state of the economy, policymakers must understand its structure. How else can they stabilize the economy? If so, however, they should be able to explain the issues relevant to that understanding. One way to challenge policymakers to explain the issues is to note that for monetary policy to be stabilizing the FOMC must solve what economists refer to as the identification issue arising from simultaneity bias. That is, the behavior of the FOMC affects the behavior of the economy and the behavior of the economy affects the behavior of the FOMC. What one sees is only the correlations of the funds rate with macroeconomic variables. How then does the FOMC sort out the one-way causation going from its behavior to the behavior of the economy?

One could argue that the FOMC just watches what happens to the economy when it changes the funds rate. Also, it is obvious which way the funds rate needs to change depending upon which objective of the dual mandate is of more concern. Those assertions raise a number of questions. First, as characterized by FOMC communication, the FOMC is choosing the funds rate one meeting at a time. What about the

Friedman (

1960) critique of long-and-variable lags? How can the FOMC know that the individual changes in the funds rate are stabilizing rather than destabilizing without knowing what will be the state of the economy when they produce their impact?

At the same time, the economy is not in a continual state of disruption. That fact would seem to contradict the Friedman critique. However, historically, the economy has gone through periods of inflation and recession. If the FOMC is managing the economy with a steady hand, why do these periods of instability recur and how does one know that they are not caused by monetary policy? Because the FOMC ignores the identification issue of sorting out the one-way causation from its actions to the economy, it does not need to address this issue. Finally, if there is a predictable relationship between fund rate changes and the behavior of the economy, both inflation and employment, one should be able to capture it through empirical estimation.

The general class of such estimated relationships is referred to as Taylor rules. However, one must deal with the fact that two very different kinds of Taylor rules fit the data. Taylor rules estimated in level form and in first difference form both fit the data. In the level form, the level of the funds rate depends upon a constant term and the misses of inflation and unemployment (output) from their targeted values (

Taylor, 1993). In the difference form, changes in the funds rate depend upon the lagged change in the funds rate and upon forecasted values of deviations of inflation from target and deviations of growth in real output from its potential value (

Orphanides, 2003). These two empirical relations are consistent with two very different structures of the economy. As argued below, level-form Taylor rules are consistent with a nonmonetary character of inflation. Difference-form Taylor rules are consistent with a monetary character of inflation.

To address these issues, there needs to be a revival of the monetarist-Keynesian debate. The central issue in this debate was whether inflation is a nonmonetary or a monetary phenomenon and how that choice is related to how well the stabilizing properties of the price system work. In the first case, the Fed is an inflation fighter. In the second case, it is an inflation creator.

Consider first the Keynesian case of inflation as a nonmonetary phenomenon. Market power by firms and unions imparts an inherent rigidity to dollar prices. Dollar prices move to clear markets only with long lags over time. As a result, changes in aggregate nominal demand, which the central bank influences but is only one factor in its determination, affect the breakdown between real variables and inflation in a predictable way. The resulting relationship between inflation and unemployment (output) is captured by the Phillips curve.

Adaptive expectations, which govern expected inflation and make it a simple geometric average of past inflation rates, mean that at its meetings, the FOMC can take inflation as given. Monetary policy can then “exploit” the Phillips curve and make it the central element in the formulation of monetary policy. Inflation is a nonmonetary phenomenon in that money adjusts through changes in velocity or through changes in its quantity as a consequence of the FOMC’s interest-rate target to validate the combination of output and inflation chosen by the FOMC. A level-form Taylor rule with independent targets for inflation and slack in the economy (unemployment) determines optimal monetary policy in the Keynesian world. In such a world, the characterization of monetary policy as discretionary is natural. There is discretion involved in choosing the weights for the misses of the two variables inflation and slack in the level-form Taylor rule.

In the Keynesian world, the unemployment rate is assumed to measure slack in the economy. As shocks impinge upon the economy, affecting primarily either output or inflation, the FOMC possesses the power to counter the unbalanced effect of the shock on the two variables. It does so by moving slack (unemployment relative to a NAIRU value, the unemployment rate consistent with no change in inflation) in a way that balances off deviations in the targeted values of the two independent objectives—in employment (output) and inflation. The trade-offs between the two variables are given by the Phillips curve. Monetary policy overrides the weak stabilizing powers of the price system to maintain a desirable combination of full employment and inflation.

In this Keynesian world, a policy of price stability produces instability in the real economy. The reason is that with a policy of price stability, powerful real forces produce relative price changes in individual markets that combine to overwhelm the stabilizing properties of the price system, causing individual markets to clear. Price stability then would require large changes in unemployment. Inflation is a nonmonetary phenomenon if the demand for liquidity (money) in the public’s asset portfolio does not exhibit a stability that counteracts the volatility in real output produced by a policy of price stability.

Among Keynesians, the instability of estimated Phillips curves leads to the belief that the structure of the economy changes over time.

Powell (

2020), FOMC chair, stated, “Because the economy is always evolving, the FOMC’s strategy for achieving its goals—our policy framework—must adapt to meet the new challenges that arise.” More to the point,

Daly (

2023), president of the San Francisco Fed, commented:

Policymakers have to respond to an economy that is evolving in real time and prepare for what the economy will look like in the future. … Before the pandemic and the current episode of high inflation, the world was starkly different. The principal and decade-long challenge for the Federal Reserve and most other central banks was trying to bring inflation up to target, rather than pushing it down. … Large structural forces were to blame. … If the old dynamics are eclipsed by other, newer influences and the pressures on inflation start pushing upward instead of downward, then policy will likely need to do more.

In the last half of the 1990s, prodded by Governor Larry Meyer, the FOMC routinely considered a level-form Taylor rule as a guide to policy, especially as a tool for forecasting inflation. However, as a guide to policy, it was not a success. As the unemployment rate declined from its cyclical peak of 7.8% in June 1992 to a low of 3.9% in December 2000, falling below staff estimates of the NAIRU, the inflation rate did not rise. In response, the FOMC concluded that it lacked the real-time information required to implement such a rule. Governor Edward Gramlich (

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 1999a, p. 45) and Governor Donald Kohn (

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 1999b, p. 69) pointed out the desirability of a difference-form Taylor rule as recommended by Board staff member Athanasios Orphanides. Alfred Broaddus (

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 1999b, p. 100) highlighted problems with using a constant term in the level-form Taylor rule to measure the underlying natural rate of interest. He also argued that the success of the Volcker–Greenspan regime came from preemptive changes in the funds rate rather than from responding only to inflation when it emerged as the FOMC did in the 1970s.

These observations about the unreliability of a level-form Taylor rule are inconsistent with the Keynesian view of inflation as a nonmonetary phenomenon. Slack in the economy (the difference between the unemployment rate and the NAIRU) is neither a useful guide to policy nor a variable under the control of monetary policy. A simple way to contrast the Keynesian and monetarist views is to note their differing treatment of the unemployment rate.

In a monetarist world, the FOMC lacks the power to manipulate slack in the economy (the unemployment rate relative to a NAIRU value) in a controlled way. The FOMC must allow the price system to work to achieve full employment. The unemployment rate is an informational variable offering information about the behavior of slack rather than a control variable. Persistent increases in the unemployment rate indicate that the economy is growing below potential. The interest rate that allows the price system to work therefore lies above the natural rate of interest and must decline to cause households to adjust the intertemporal pattern of their consumption in favor of the present (increase it) to keep aggregate demand equal to potential real output. Converse statements hold in the case of persistent decreases in the unemployment rate. Stability in the rate of unemployment means that there is no slack in the economy in the sense of an undesirable underutilization or overutilization of resources. A difference-form Taylor rule with its measure of forecasted changes in the economy’s rate of resource utilization (changes in output growth) as the independent variable captures this behavior of monetary policy.

A steady unemployment rate is evidence that the FOMC has moved the funds rate in line with the natural rate of interest, and the price system is maintaining full employment. The FOMC is allowing the stabilizing powers of the price system to maintain full employment. Deviation from these procedures is the macroeconomic equivalent of price fixing. The resulting imbalances in the bond market, given the Open Market Desk’s defense of the FOMC’s interest rate peg, result in money creation (destruction) that destabilizes the price level. A monetarist policy of price stability focuses monetary policy on the sole objective of stability in underlying inflation. Necessarily, such a policy turns over the behavior of the real economy (output and employment) to the stabilizing properties of the price system. A policy of price stability causes the stabilizing properties of the price system to work to cause individual markets to clear in order to maintain full employment.

To make clear the relevance of this monetarist view to current central bank practice, numerous hurdles must be overcome. These hurdles are created by the FOMC’s use of the language of discretion, which obscures the role of the price system and the way that the underlying consistency in policy shapes expectations. First, as described in

Section 7, monetary policy controls a nominal variable—money creation. The FOMC’s LAW procedures, which move the funds rate to counter unsustainable strength or weakness in the economy, are also consistent with a model in which the FOMC is controlling slack in the economy—a real variable. Only experiments like the monetary policy of the 1970s, in which the FOMC actively tried to control unemployment to keep it at 4%, can distinguish between these monetarist and Keynesian constructs.

Second, the consistency in monetary policy shapes the expectation of the future value of money in terms of the value of money today. The expectation of price stability means a dollar today and tomorrow exchange for the same amount of a basket of goods. The price of money, which is the inverse of the price level, remains stable. Again, only the experiments the FOMC has conducted with changes in monetary policy make this fact clear. By the end of the 1970s, the expectation of inflation had become a random wall moving with actual inflation. Only the discipline (underlying rule) imposed in the Volcker–Greenspan era restored the nominal anchor lost in the 1970s. If inflation were a nonmonetary phenomenon, the FOMC would lack this power.

Third, the fact that the measured monetary aggregates (M1 and M2) no longer predict the near-term behavior of the economy does not mean that the relevant measure, which is the overall liquidity in the public’s asset portfolio, is not characterized by a stable demand function. Consider M1. In the early 1980s, the cost of electronic transfers between bank deposits and money market instruments like short-term Treasury bills fell. At the same time, volatility in money-market interest rates increased significantly. Moreover, banks change the interest rates they pay on their deposits only with a long lag behind the change in money market rates.

Consider now a weakening of the economy and a decline in money market interest rates. Investors in the money market transfer funds from money market instruments with predominantly savings characteristics to the now higher-yielding bank deposits, which normally are used for transactions. Because of this changing composition, the increase in M1 does not reflect a commensurate increase in the liquidity of the public. As a result, in the early 1980s, the behavior of M1 changed from being procyclical to being countercyclical. M1 then began to offer misleading signals about the stabilizing behavior of the funds rate by strengthening when the economy weakened. An analogous story holds in the case of a strengthening in the economy with higher money market interest rates and a diminution in M1 growth.

The fourth hurdle is the simplistic exposition of the quantity theory widely assumed to be the framework advocated by monetarists, regardless of whether the central bank targets bank reserves and money or whether it uses the interest rate to implement policy. That is, aggregate nominal demand is determined by the equation of exchange exposited by Irving Fisher with money controlled by a reserves-money multiplier. As long as the empirical constructs for liquidity, M1 and M2, possessed predictive value for the economy and for inflation and their behavior was procyclical, monetarists could make a case for explicit procedures to control money understood with that construct. However, they never explained what kind of rule could provide for the monetary control required for price stability with the funds rate as the instrument. At first pass, monetarism then appeared irrelevant as an explanation for the restoration of price stability in the Volcker–Greenspan era, given the absence of targets for money or reserves.

In the monetarist world, there is no inherent inflexibility in market-clearing relative prices. As explained by

Lucas (

1972/1981), the optimal rule is one of price stability. Price stability then does require firms to separate the behavior of relative prices from changes in the price level. A rule ensuring price stability separates the determination of the price level and employment. That is, the rule creates a “classical dichotomy” or “divine coincidence” in that price stability and full employment occur jointly. The price system is then free to allocate resources to their most productive uses, as explained by Adam Smith.

To render more precise the differences in the policies followed when the FOMC held one or the other of the two views of the world, Keynesian or monetarist, it is useful to start with the common baseline of each for monetary policy. Since the creation of the modern central bank by William McChesney Martin, the baseline policy has remained “leaning against the wind” (LAW). With this policy, the FOMC lowers the funds rate if it judges that the economy is growing in a sustained way at a rate below potential. That is, the economy’s rate of resource utilization is declining persistently (the unemployment rate is rising persistently). Conversely, the FOMC raises the funds rate if it judges that the economy is growing in a sustained way at a rate above potential. Note that LAW imposes a consistency on monetary policy over time, which the FOMC ignores when it places fund rate changes solely in the context of discretionary actions in its public communication. (See

Hetzel, 2022).

At various times, the FOMC has implemented one or the other of two variations of LAW. The Keynesian version is termed here “LAW with trade-offs” and the monetarist version “LAW with credibility” (

Hetzel, 2022, Chapters 17 to 20). LAW with trade-offs is descriptive of policy in the 1970s under FOMC chairs Arthur Burns and G. William Miller. In the 1970s, the FOMC implemented LAW in a way that imparted cyclical inertia to the funds rate. It did so as a consequence of having two independent targets: an assumed socially-desirable low rate of unemployment, taken to be 4 percent and a low rate of inflation. During periods of economic recovery, the FOMC raised the funds rate vigorously only when inflation began to rise. In that way, it could feel assured that it had reached its goal of full employment. Money growth was procyclical. Inflation followed economic recovery, and recession followed the rise in inflation when policy tightened. Inflation rose irregularly over the decade of the 1970s and peaked in 1981.

By the time that Paul Volcker succeeded G. William Miller as FOMC chair in August 1979, as noted above, the United States had lost a nominal anchor. Expected inflation moved with actual inflation. Volcker and his successor, Alan Greenspan, both directed policy toward reestablishing a nominal anchor in the form of the expectation of price stability. The bond market vigilantes held the FOMC’s feet to the fire. Having lost significant amounts of money in the decade of the 1970s, they associated any sign of an expansionary monetary policy allowing sustained strong growth in real GDP with future inflation. Accordingly, they raised bond rates in a phenomenon that came to be called “inflation scares” (

Goodfriend, 1993). By raising the funds rate in response to inflation scares, monetary policy necessarily rejected any attempt to exploit a Phillips curve trade-off.

LAW with credibility replaced LAW with trade-offs. By concentrating on the restoration of price stability, monetary policy effectively turned over the determination of real variables to the working of the price system. Its most dramatic departure from LAW with trade-offs was preemptive increases in the funds rate to prevent the emergence of inflation. After 1994, following significant increases in the funds rate with no recession, Greenspan tamed the bond market vigilantes. A policy of price stability became credible. The signal for preemptive increases in the funds rate then became signs of overheating in the labor market.

11. Monetary Control and the Behavior of M2

A framework that is relevant when the central bank uses an interest rate as its operating target still starts with the assumption that price stability requires monetary control. That monetary control, however, depends upon the rule the central bank follows and need not involve targets for money. The behavior of M2 and inflation in the post-Great Recession period is illustrative.

The issue is, when does reserve creation lead to inflation and when does it not? First, even significant acquisition of treasury securities, which creates reserves and bank deposits, does not always lead to inflation. From 1970Q1 through 2007Q4, Federal Reserve bank credit as a percent of GDP (Federal Debt Held by Federal Reserve Banks as Percent of Gross Domestic Product) remained steady at around 5%.

4 Nevertheless, this period included both inflation and price stability. That is, price stability did not necessarily follow from stability in the extent of the FOMC’s monetization of government debt. Second, even though over the period 2008Q1 through 2019Q4 the above ratio rose from 4% to 12%, price stability prevailed. In contrast, from 2019Q4 the ratio rose to a peak of 18.7%—a period of high inflation.

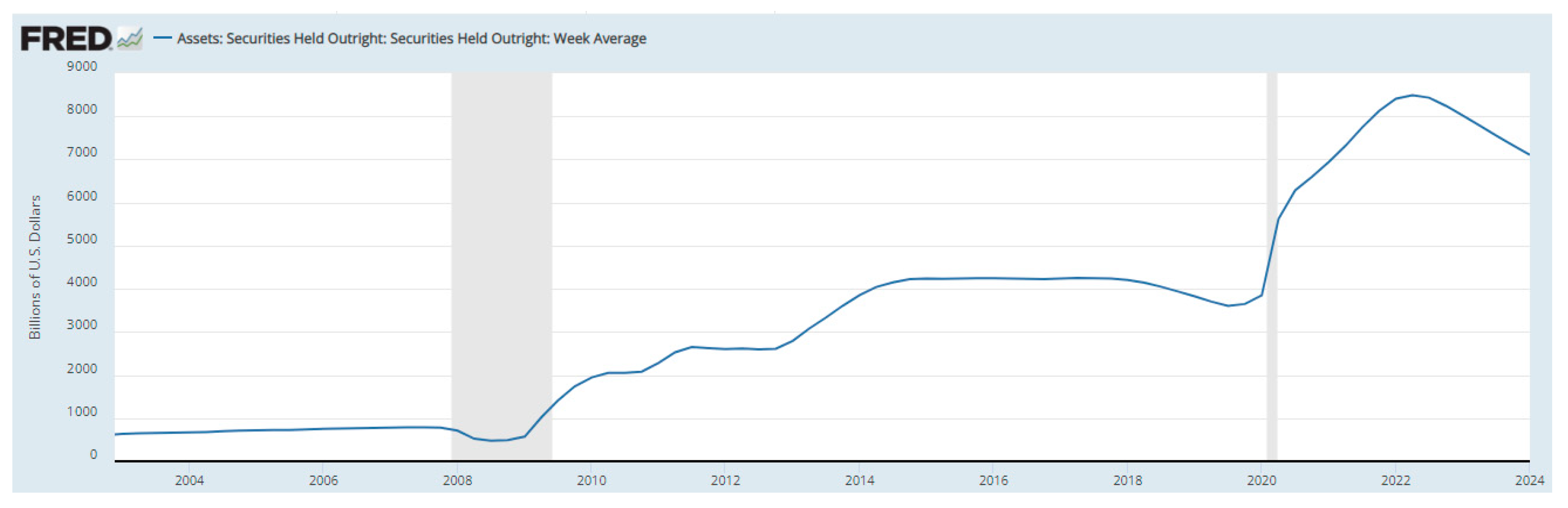

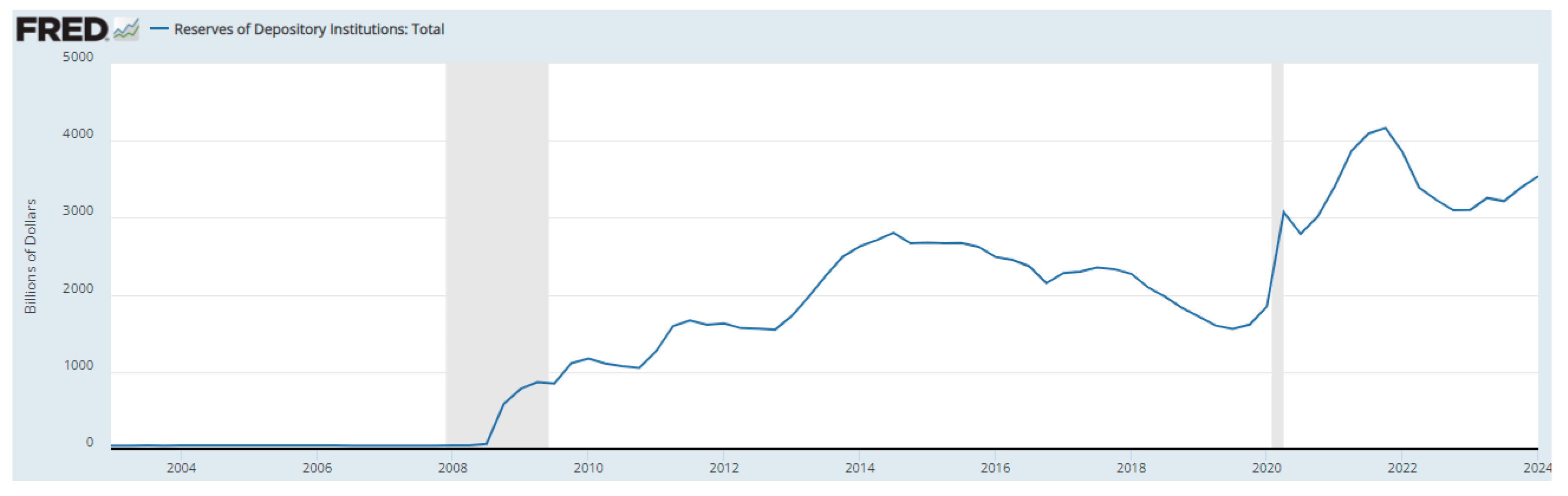

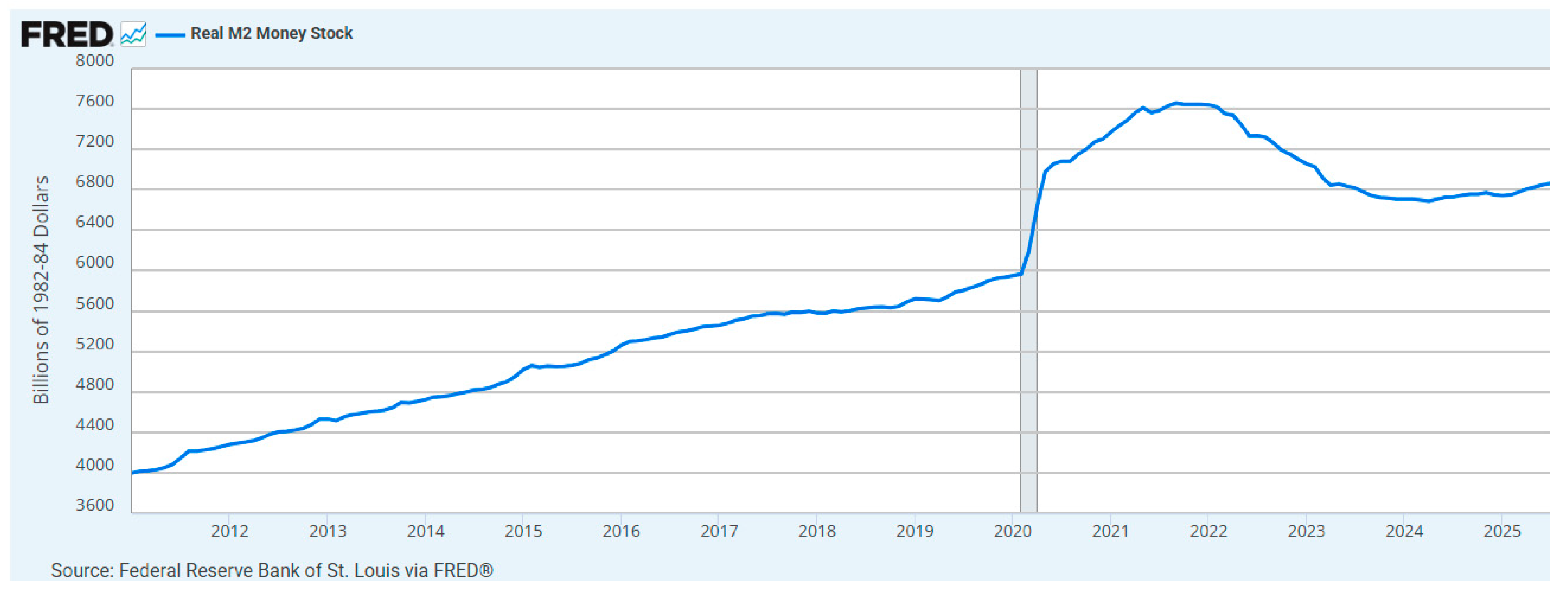

Figure 1 includes the episodes of quantitative easing (QE) following the end of 2008, when the Fed purchased treasury securities, mortgage-backed securities (MBS), and government-sponsored enterprise (GSE) debt and the funds rate was at the zero lower bound (ZLB). QE occurred starting in late 2008 and lasted through 2013Q4. It reoccurred in the pandemic period from 2020Q1 through 2022Q1. Why did inflation occur in the later but not in the earlier period? The reserves of commercial banks held at the Fed increased in both periods (

Figure 2). However, as shown in

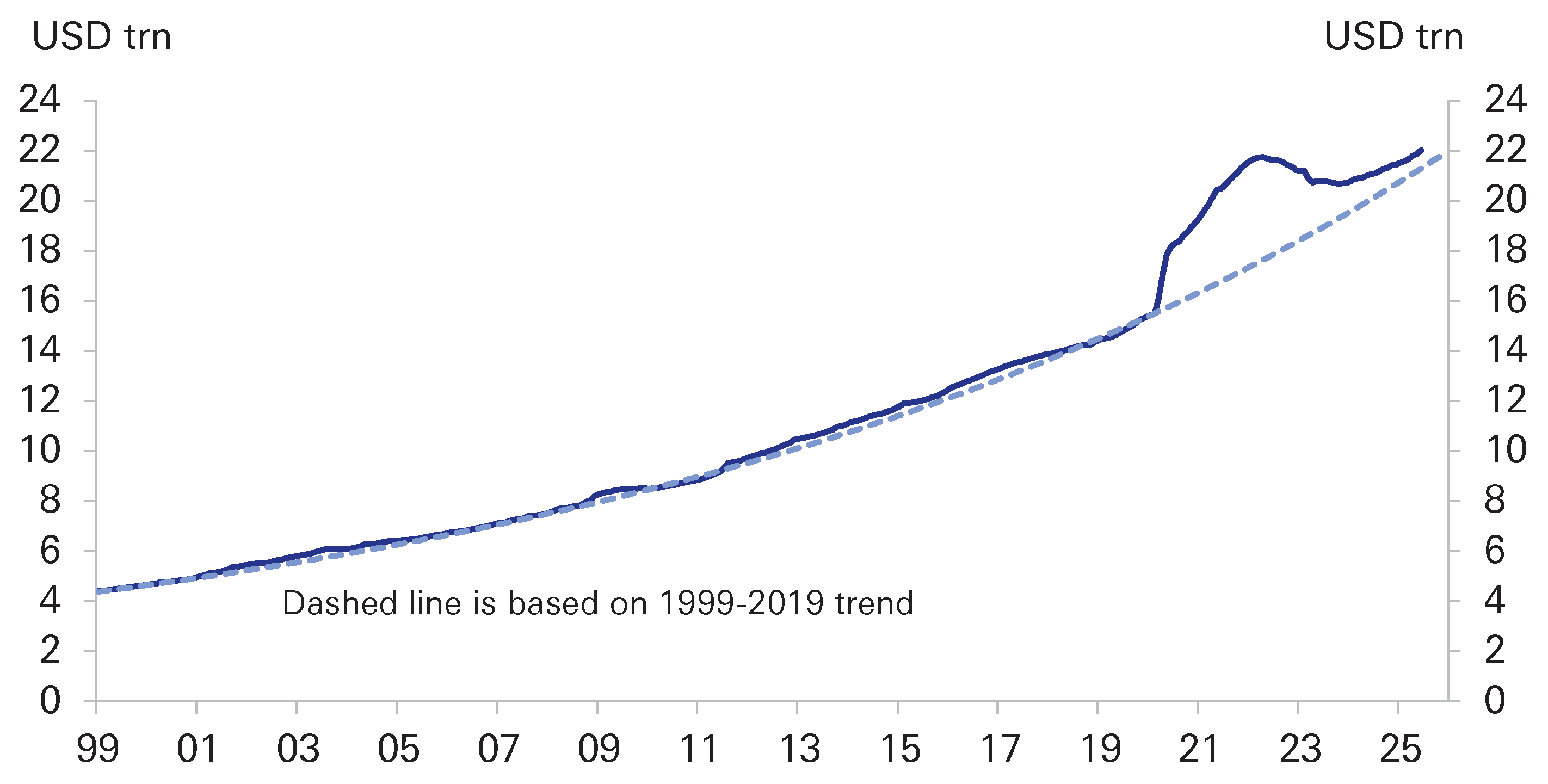

Figure 3, in the earlier period, M2 grew steadily but then rose sharply in the succeeding pandemic period.

As shown in

Figure 3, in the pandemic period, QE caused a bulge in M2.

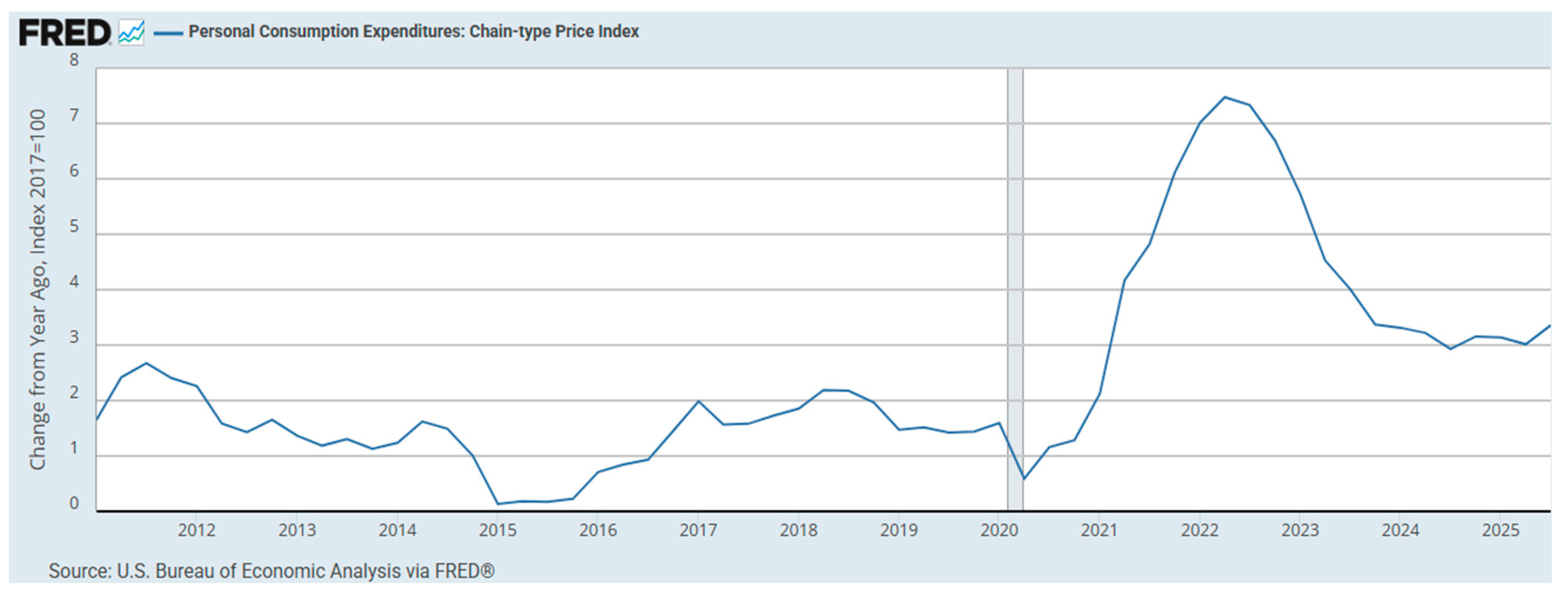

Figure 4 shows inflation.

Figure 5 shows that the inflation burned off the excess M2 created by Fed monetization of the debt issued to finance the pandemic payments. That conclusion is supported by the fact that real M2 began growing again moderately after declining significantly following the pandemic bulge.

To explain the difference in inflation between the pre-pandemic and post-pandemic periods, it is necessary to understand the difference in the behavior of M2. Why did M2 behave differently in the two periods, with moderate growth in the first period and strong growth in the second period, despite strong growth in bank reserves in each period? The answer lies in whether the FOMC was following procedures that tracked the natural rate of interest. Starting with the Great Recession, note also that it is important to take account of the distorting flows that prevented M2 from forecasting the near-term behavior of output. M2 did not decline in the 2008–2009 recession as it had historically in recessions. With the failure of Lehman Brothers on 15 September 2008, cash investors in the institutional money funds and investment banks concluded that the Fed had limited the extent of the financial safety net. However, too-big-to-fail remained in place. Cash investors then transferred funds to the too-big-to-fail banks like JPMorgan Chase. The resulting increase in bank deposits increased M2.

A central factor in the story is to understand that monetary policy was moderately contractionary in the first part of the recovery from the Great Recession (

Hetzel, 2022, Chapter 24). Based on historical experience, strong recoveries had always followed deep recessions. For that reason, bond markets anticipated a strong recovery and yields on bonds remained high.

5 The problem was that the natural rate of interest was negative and monetary policy was contractionary even with a near-zero funds rate. Later, Board staff documents provided evidence of a negative natural rate of interest. For example, the Tealbook for the 25–26 January 2011, FOMC Meeting (

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 2011, p. 36) showed −1.7 percent for the “Tealbook-consistent FRB/US-based measure of the equilibrium real funds rate (current value).” (FRB/US is the econometric model used by the staff of the Board of Governors) (See

Hetzel, 2022, Chapters 21, 22, and 24).

Unlike European central banks, the FOMC did not make its policy rate negative. Instead, it turned to QE. Working through a portfolio balance effect (Tobin’s Q), QE raised the natural rate of interest. The purchase of illiquid long-term bonds from the public, which created liquid bank deposits, increased the liquidity of the public’s asset portfolio. Rebalancing raised the price of illiquid assets like equities and houses, which stimulated investment. QE maintained the recovery even with a weak world economy and a Eurozone crisis in 2011 and 2012.

Only if FOMC procedures are holding the real funds rate below the natural rate of interest do the reserves and money creation caused by QE become inflationary. As just described, through the portfolio balance effect, QE raises the natural rate of interest. However, banks will just hold the reserves created through QE without attempting to run them down as long as the rise in the funds rate and the rise in IOR track the natural rate of interest when it rises above zero. Starting in December 2016, the Yellen FOMC began to raise the funds rate in a sustained way. It tracked the rise above zero in the natural rate of interest.

As long as the funds rate tracks the natural rate of interest and the expectation of price stability holds, the FOMC can maintain price stability. The banking system accommodates the increase in the demand for money, which is limited to the increased demand desired by the public due to the growth in potential real output. Until the expansionary monetary policy of the pandemic, M2 grew moderately in line with demand, which was augmented moderately by the low level of short-term interest rates. Monetary control consistent with price stability disappeared with the expansionary activist aggregate-demand policy adopted during the pandemic. Money creation then became a source of disturbance. The FOMC regained control of money creation through a combination of the significant increase in the funds rate starting in March 2022, combined with the replacement of QE with quantitative tightening (QT). Monetary policy again began tracking the natural rate of interest. Growth in nominal output began to grow in line with growth in potential real output.

Because of the extended preceding period of near price stability, despite the large rise in inflation in 2021–2022, inflationary expectations remained anchored. The strong rise in the funds rate between March 2022 and July 2023, which brought the funds rate into closer alignment with the natural rate of interest, reinforced this expectational stability. The rise and then the decline in inflation demonstrated the

Friedman (

1968/1969) one-time helicopter drop of money. As a result, there was a one-time increase in inflation until real money balances returned to their desired level. Unlike the 1970s, when the FOMC continued an inflationary monetary policy until expected inflation rose and then required a recession to quell the rise, the inflation of 2021–2022 did not trigger a rise in expected inflation. The rise in inflation (PCE implicit deflator, quarterly) that began in 2020Q3 at 3.3% and peaked in 2022Q2 at 7.6% before falling sharply to 3.4% in 2023Q4 resulted from a one-and-done helicopter drop of money caused by the FOMC’s monetization of pandemic payments to the public.

12. Should the Fed Be Involved in the Allocation of Credit?

With the 1951 Treasury–Fed Accord, the Fed took responsibility for causing aggregate nominal demand to behave in a stabilizing way. However, the FOMC never formulated procedures for the explicit control of aggregate nominal demand. The issues that need addressing in order to fill this void are numerous, and the continuing silence from the Fed is unfortunate. One issue concerns the advisability of becoming involved in the allocation of credit. Since the creation of the modern Fed by William McChesney Martin and his “bills only” policy of holding only short-term Treasury bills, the Fed has carefully avoided becoming involved with the allocation of credit as a threat to its independence from political pressures. That separation of monetary and credit policy ended in fall 2008 with the reinvention by FOMC chair Ben Bernanke of the Fed as a combination housing GSE and central bank.

Financial markets became roiled when the Fed allowed Lehman Brothers to fail on 15 September 2008. That failure broke with the tradition of not allowing financial institutions of any sort to fail with losses to debt holders—a policy known as too-big-to-fail since the Fed bailed out Continental and its holding company in 1984, which suffered from losses in foreign exchange speculation. However, too-indebted to fail is a more accurate description. After bailing out Bear Stearns, IndyMac, and the GSEs Fannie and Freddie earlier in 2008, the failure of Lehman left markets shocked and uncertain about the extent to which the Fed had retracted the financial safety net. Depositors in prime money market funds and holders of the short-term debt of the investment banks fled to the too-big-to-fail banks like JPMorgan Chase.

“There’s no doubt in my mind Lehman Brothers would have solved its own problems earlier on,” Bair explained. “It would have sold itself, raised more capital, all the above, if they hadn’t thought in the back of their minds ‘they wouldn’t dare not bail us out. We’re bigger than Bear Stearns.’ That’s the problem. That’s the expectation that you create. Then you don’t do a bailout, and … you really have the system seizing up, as we saw when Lehman Brothers went into bankruptcy.”

The Fed became involved in credit allocation to undo the reallocation of investors’ funds from the investment banks to the too-big-to-fail banks. It then moved on to support the housing market through large-scale acquisitions of mortgages and GSE debt.

Following the Lehman failure, the bailout of AIG, whose holding company lost money from insuring against losses incurred by institutions holding subprime home mortgages, led to the widespread public perception that the economy is rigged in favor of the wealthy. That perception fed the populist movement against free markets. Ironically, the financial safety net removes financial intermediaries from the market discipline to which nonfinancial companies are subject. The resulting moral hazard that skews risk-taking among financial institutions makes the presence of the Fed in financial markets even more pressing through extensive regulation. The market is rigged but by the financial safety net, which removes the market from the role of regulating bank risk-taking.

The failure of the California bank SVB in 2023 shows the box that regulators have gotten themselves into because of the financial safety net. Withdrawals occurred so quickly due to bank apps that regulators could not take SVB over on the weekend and sell it to a solvent bank while putting in FDIC funds to prevent losses to uninsured depositors. Large depositors with uninsured deposits in regional banks then began to move funds costlessly to the large too-big-to-fail banks. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen and FOMC chair Jerome Powell together stopped the run through an implicit assurance that all deposits, uninsured as well as insured, were covered—an authority never granted by Congress. Regulators dislike financial disorder on their watch, and the public has no way of assessing their “Henny Penney the sky is falling in” arguments about letting a bank fail with losses to uninsured depositors.

Shelia Bair contended that the implicit promise to bail out all uninsured depositors itself created panic from the fear that the regulators believed that the entire banking system was troubled.

Coggins (

2023) reported on Bair’s views:

As the markets respond to the bailout of SVB and Signature Bank as well as the rescue of First Republic, Bair noted that fear is starting to mount for the banking system and uncertainty is spreading. … According to Bair, actions taken by the government have created “mass confusion” that could cause efforts to support the banking system to backfire. Acknowledging there are some banks with problems, she also emphasized that only a small percentage of the overall banking system has issues. “[The government is] trying to imply that all uninsured depositors are protected, which they don’t have legal authority to do, frankly, and this is putting pressure on community banks” she said. “It’s really troubling. I think the better way to communicate would have been to handle these two bank failures with the regular FDIC process …” she said. “Remind people there are deposit insurance limits, remind people that some banks can and do fail. They need to be vigilant and leave it at that.”

Consider the vast expansion of credit allocation using a panoply of credit programs under FOMC chair Jerome Powell, with the recognition in March 2020 of the widespread spread of the COVID virus. Naturally, with the uncertainty over the extent and duration of the virus and without a vaccine anywhere on the horizon, long-term investors postponed investment decisions. The Powell Fed, however, talked about markets “freezing up” and began a wholesale intervention into the allocation of credit. It never explained why the Fed is better at assessing risk and allocating credit than investors with their own money on the line.

The vast expansion of the Fed’s balance sheet that began in early 2009, made possible by the payment of interest on bank reserves (IOR), has allowed the Fed to function as a financial intermediary. One consequence is that, as banks accumulate reserves, they have no need for an interbank market in which they can trade with other banks to deal with temporary shortages and excesses of reserves. With the atrophying of the federal funds market, the funds market is now reserved for the GSE’s, which have no settlement account with the Fed. Banks then do not assess the creditworthiness of other banks. As explained by

Nelson (

2024), every increase in the Fed’s balance sheet just ratchets up the size of the balance sheet required for market stability. Over time, the result has been that the Fed has come to associate volatility in money markets with instability requiring a large balance sheet and large amounts of bank reserves.

Adding the removal of volatility in money market interest rates as an unstated financial stability goal will create an impossible dilemma for the Fed in the event of a financial crisis. Such a crisis is a real possibility given the failure of the political system to deal with an unsustainable fiscal deficit. At some point, bond rates will rise. Especially given the size of the Fed’s asset portfolio, it will come under pressure to buy bonds with the plea that the political system requires time to work out the difficult political compromises required to enact some combination of spending cuts and tax increases. The pressure will also exist not to increase the IOR to make banks willing to hold the additional reserves created. Given the failure of the Fed to explain how it creates inflation, it will lack convincing arguments as to why such bond purchases will be inflationary. Without being able to talk about money creation, it lacks the ability to talk about the determination of inflation. Simply noting that central banks lacking independence in countries like Turkey have high rates of inflation will be insufficient to defuse the pressures.