1. Introduction

ProShares introduced the first leveraged exchange-traded fund (LETF) in 2006, although the concept of multiplying an index’s return went back to at least 1993 with Rydex’s 1.5× mutual fund RYNVX. However, it is within the ETF market where LETFs exploded in popularity, now boasting over 170 funds with more than $100 billion in assets, multiplying a variety of underlying indexes and even individual stock returns on U.S. markets.

Most of these funds multiply the underlying index’s daily return by up to ±3.0×. On the London Stock Exchange, there are funds that multiply daily returns up to 5.0× such as Leverage Shares SP5Y. On the U.S. markets, newly introduced LETFs are now limited to ±2.0× due to the Securities and Exchange Commission’s (

SEC, 2020) Derivative rule (18f-4), although BMO listed an exchange traded note (SPYU) with 4.0× daily leverage in December of 2023 (

Comtois, 2023).

LETFs by their very nature magnify both the return and volatility of an underlying index by their respective leverage ratios. Over an extended holding period, LETFs experience leverage drift, which is usually negative, meaning a 2.0× daily LETF will provide less than a 2.0× cumulative return for extended holding periods. The funds warn about these effects and highlight that these instruments are for short-term holdings. The Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) issued a warning in June 2009 (Regulatory Notice 09-31) that “inverse and leveraged ETFs that are reset daily typically are unsuitable for retail investors who plan to hold them for longer than one trading session, particularly in volatile markets.”

In response to this short-term mindset, AXS investments through Tradr introduced calendar LETFs in 2024 (

Benjamin, 2024). Rather than targeting a daily multiple, these LETFs target monthly and quarterly multiples. In theory, this eliminates leverage drift due to compounding effects through the reset period, excluding management and finance fees.

Currently, all LETF prospectuses display tables such as

Table 1 detailing the expected returns of LETFs for annual holding periods. This is to demonstrate how realized leverage can be greater or less than the specified leverage over time depending on the underlying annualized return and standard deviation of the index.

The model LETF providers use to create these tables is only relatively accurate for moderate return/volatility assumptions over an extended period and is given by:

where

LRT is the return to the leveraged fund,

XRT is the underlying index return,

β is the leverage ratio, and

is the variance over the time interval

T (

Cheng & Madhavan, 2009;

Avellaneda & Zhang, 2010).

The error occurs primarily due to using an approximation method to annualize the standard deviation although there is an additional error in calculating the geometric mean. This latter error is relatively small for daily LETFs but can be larger for the longer reset calendar LETFs. The significance of the above errors at higher return/volatility assumptions becomes quite large and misconstrues the relationship between daily vs. calendar LETFs as well.

This study derives statistically correct values for LETF expected returns over time relative to underlying index returns and shows how the current method being used to project LETF returns produces estimates that can deviate from their statistically correct values by up to ±100% or more in absolute return under extreme return/volatility assumptions. The returns generated by using statistically correct methods are confirmed by Monte Carlo simulation and realized empirical results.

Additionally, comparisons are made for daily, monthly, and quarterly reset calendar LETFs, showing the longer reset LETFs outperform during periods of average to high volatility while daily LETFs will outperform in periods of high trend and low volatility. This contrasts with conclusions that might be reached using current tables published in LETF provider prospectuses.

The implications suggest the expected returns to longer-term holdings of bullish LETFs in more extreme market environments are not as dire as current prospectuses suggest. This is even more relevant today, as there are now multiple LETFs on highly volatile single assets such as Tesla, Nvidia, Apple, and Bitcoin to name a few. In addition, the method used in this study clarifies what returns can be expected and the differences between daily and calendar LETFs, which should help investors make better informed decisions. The results have implications for risk assessment, product design, and regulators who have perhaps been too focused on warning investors about how these instruments are for short-term trading only.

2. Literature Review

In 2008, Direxion upped the leverage ante by introducing ±3.0× funds. The financial crisis that ensued soon thereafter with its associated market volatility resulted in cumulative returns for LETFs that were well short of what their daily leverage ratio might imply. In several instances, especially for inverse LETFs, the volatility led to negative cumulative returns despite the underlying index being down as well. This led to unfavorable press and lawsuits, (

Maxey, 2009;

Zweig, 2009).

Carver (

2009) even suggested LETFs “converge to zero,” which is generally true for inverse LETFs, as they decline in value due to the general upward trend of most indexes and through volatility decay. In addition, the SEC said, “some of the funds generic disclosures about derivatives may be of limited use,” causing fund providers to increase their education about these funds, (

Mankelow, 2010).

Fortunately,

Cheng and Madhavan (

2009) derived a model showing the relationship between a LETF’s return and its underlying index’s cumulative return. Due to daily compounding, the realized leverage over time is a function of leverage, volatility, and the trend of the underlying index. This is shown by Equation (1) and

Table 1 in the previous section. Equation (1) is currently used to derive values shown in Proshares, Direxion, GraniteShares, and Tradr prospectuses today among others.

Avellaneda and Zhang (

2010) simultaneously developed a similar model while also accounting for the expense ratio and implied borrowing cost. The early conclusion about LETFs was they should be used for short-term trading strategies. However,

Guedj et al. (

2010) show it is likely investors hold LETFs for extended holding periods with up to 8% holding for longer than three months.

Trainor (

2011) went on to show LETFs could be successfully held for extended periods covering decades if the volatility of the underlying asset was sufficiently muted. This was followed up by

Scott and Watson (

2013) who after accounting for financing and management costs, concluded LETFs could be used in retirement portfolios by investing 15% in a 3.0× LETF and 85% of the portfolio in risk-free type assets.

Tank and Xu (

2013) pointed out the importance of trend and volatility effects by separating out compounding and management effects in explaining why daily LETFs deviate from what might be naively expected. They showed that deviations from the initial leverage over time is a function of compounding issues, interest expense related to the SWAPs used to create leverage, and expenses ratios. Out to 40 days, the interest and expense ratio effects can be at least as significant as the compounding effect, at least when related to realized leverage over time.

Charupat and Miu (

2014) also disentangle the compounding effects from the financing and management costs but conclude the compounding effect has the greatest influence on realized leverage over time.

Chan (

2025) reaffirms that LETFs experience significant volatility drag during the 2020 to 2024 period, especially in the more volatile markets, but even fixed-income LETFs still showed significant decay.

Following

Scott and Watson’s (

2013) barbell type methodology,

George and Trainor (

2017) and

Trainor et al. (

2020) demonstrated how LETFs could be used as portfolio insurance and the primary components of a portfolio.

Smirnov and Smirnov (

2020) and

Smirnov (

2021) find similar positive results using LETFs in a portfolio framework to increase returns and reduce drawdowns.

Balter et al. (

2025) along with

Van Staden et al. (

2025) reaffirm this idea with the latter showing how LETFs can be used in long-term portfolio construction to outperform benchmarks.

Glenn (

2021) pointed out how LETFs have made great long-term investments and provided a strategy to help mitigate drawdowns while

Hsieh et al. (

2025) reaffirm LETFs outperform their daily leverage ratio over time in momentum-driven markets. In addition, they show weekly or monthly rebalancing reduces decay in oscillating markets.

This last finding ties directly into AXS Investments introduction of calendar LETFs in September of 2024. Up until that time, monthly leverage was limited to mutual funds and exchange traded notes (ETNs), none of which drove much interest. Academic studies in this area are limited, but

Trainor (

2012) found monthly leverage does reduce the compounding problem through approximately six months.

Yuan et al. (

2021) have similar findings while also demonstrating the monthly leverage fund’s rebalancing needs at the end of the month are relatively large compared to daily leveraged funds. This could result in higher market volatility on rebalance days if these funds became large enough relative to the indexes they follow. Both studies pointed out the interim leverage issue between rebalance dates in that if the index is above (below) the initial start value, effective leverage will be less (more) than the stated leverage.

In summary, there is a large body of work that is positive about the use of LETFs for long-term holding periods. It is thus critical that the underlying theoretical model before adjusting for financing and management costs calculates long-term expected returns accurately relative to the underlying index.

The basic structure of

Cheng and Madhavan’s (

2009) model is relatively accurate ex-post when using realized daily volatility return inputs that result in the long-term underlying index return. However, the approximation used to attain daily values of the mean and standard deviation when making ex-ante projections based on an underlying index’s annual return and standard deviation lead to large errors in extreme environments. The current method in use does not lend itself well to the monthly or quarterly LETF projections with fewer observations over any period. This study provides a statistically correct method to calculate the effects of compounding regardless of the leverage or reset period and correctly shows the relationship between daily and longer reset LETFs.

3. Calculating LETF Expected Returns Relative to Underlying Index

3.1. Arithmetic to Geometric Mean Approximation

The current method used to estimate LETF expected returns over extended holding periods make use of approximations to convert (1) an arithmetic mean into a geometric mean and (2) conversion of a daily variance into an annualized variance.

To convert an arithmetic mean into a geometric mean, the following approximation method is used:

where

is the geometric mean and

is the arithmetic mean. This calculation always understates the true geometric mean although the error becomes small as the number of periods (N) approaches infinity (

McCulloch, 2003). The exact formulation is:

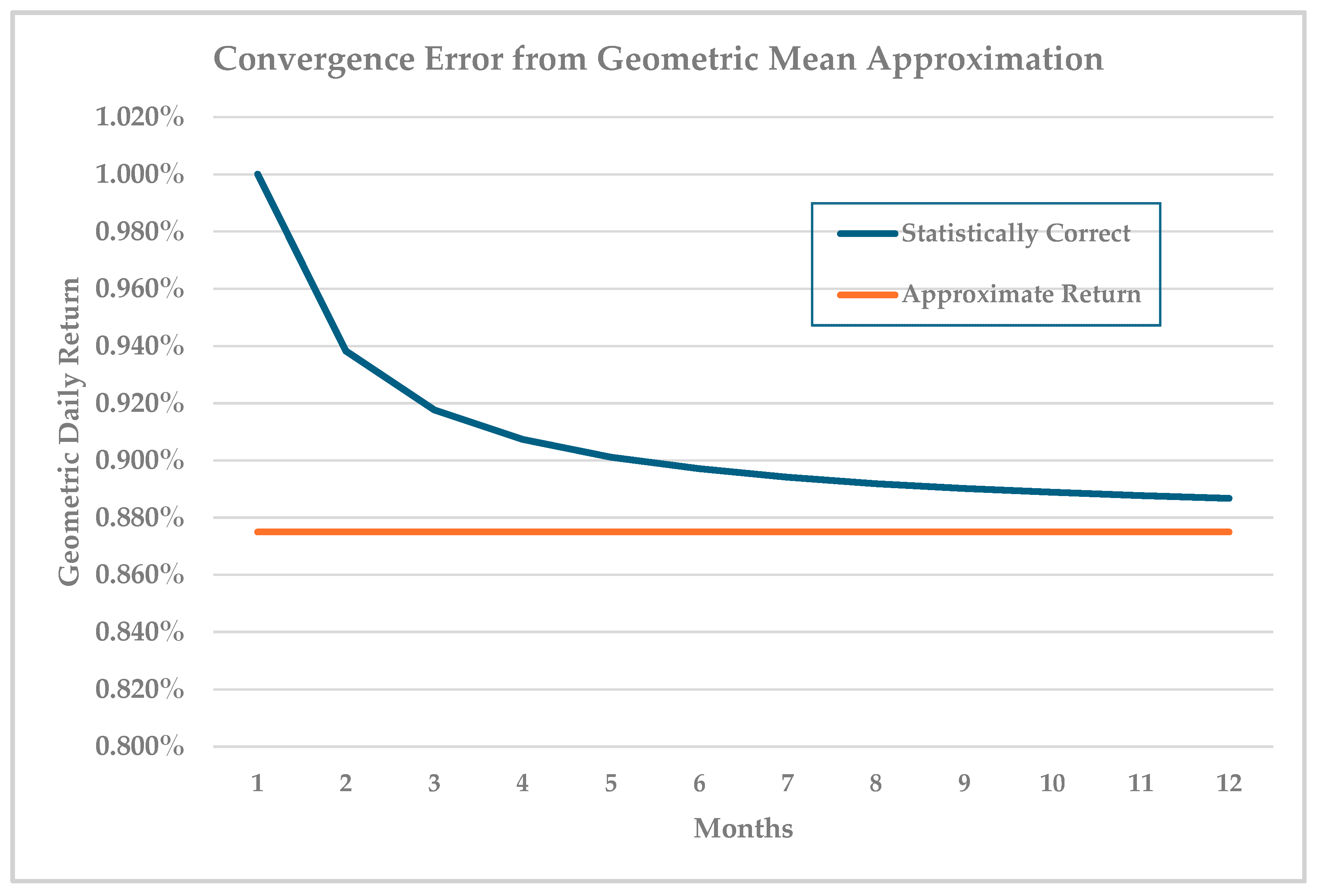

Figure 1 highlights the error for monthly returns based on a 1% monthly return and 5% standard deviation. For daily returns, the approximation is relatively accurate even by a month as N is large, but this is not the case for the longer calendar monthly and quarterly rebalanced LETFs. For the calendar LETFs, Equation (3) should be used to calculate the underlying daily index return

.

3.2. Annualizing Standard Deviation Approximation

The annualized standard deviation approximation is given by the following:

where

σt is the standard deviation of period t usually specified in days or months, and N is the number of periods in a year. This is only approximately correct, as the standard deviation is also a function of the return (

Tobin, 1965;

Kaplan, 2012;

Weber, 2017). The correct formulation is:

where

μt is the expected value of the return period and should be found using Equation (3) instead of Equation (2), although this creates a mathematical problem, as there is no closed-form solution. The approximating formula overstates the standard deviation when the return is negative and understates when the return is positive.

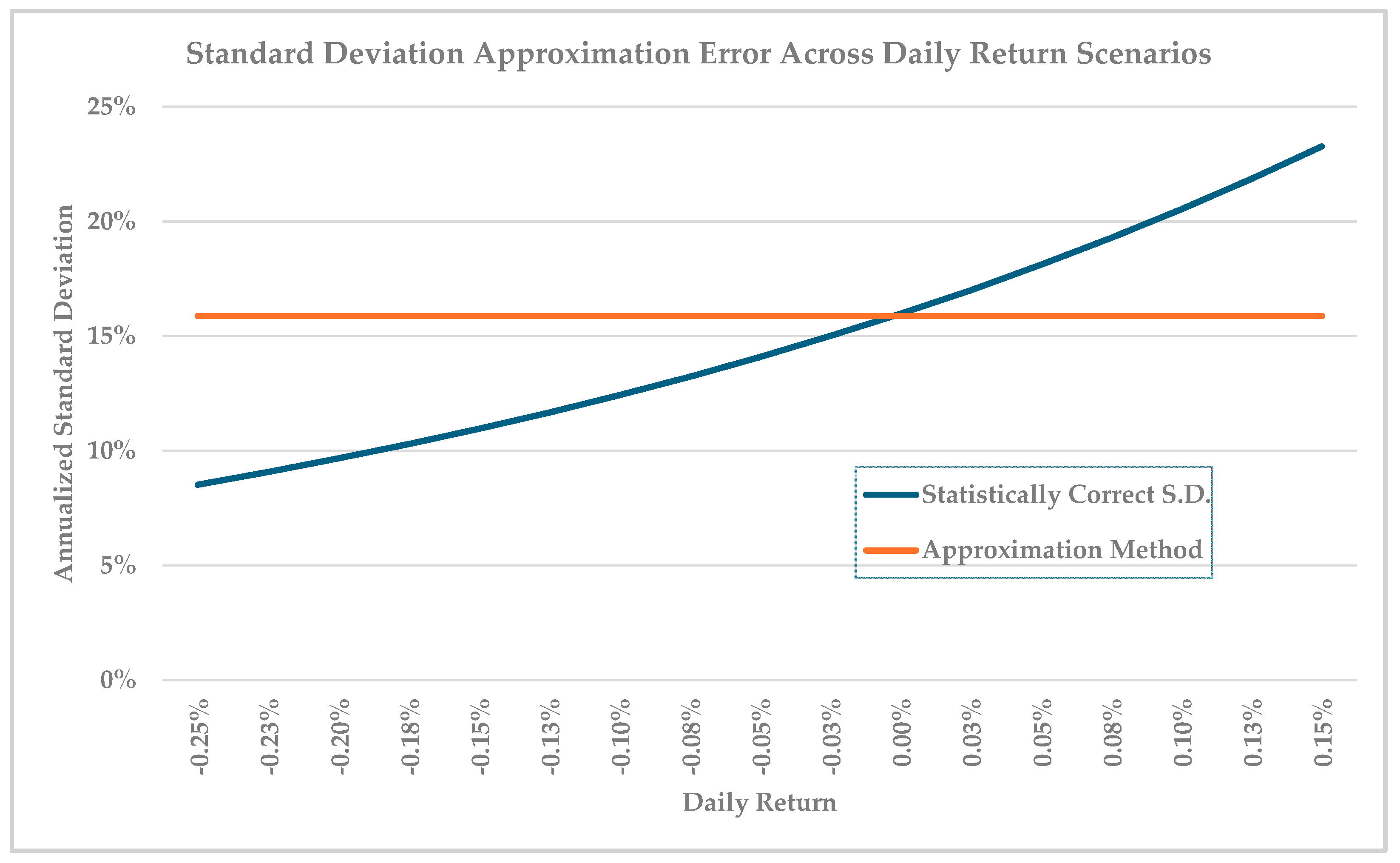

Figure 2 shows how large this error can be by using the S&P 500 average daily standard deviation of 1%. Using the approximation method, deviations from the statistically correct values range from 7% too high for a negative average daily return of −0.25% (−47% annualized…but only approximately) to 14% too low for a 0.25% daily return (88% annualized, approximately).

This error is especially relevant to LETFs, as they magnify both the daily return and standard deviation by their leverage ratio. Relative to any underlying index, LETF’s annual standard deviation over time is not just leverage times the annual standard deviation of the index but the leverage times the underlying index’s daily mean and standard deviation (month or quarter for the calendar LETFs) within Equation (5). The correct formulation for the annual standard deviation of the LETF where L is the leverage ratio is shown in Equation (6):

3.3. The Approximation Method for LETF Expected Returns

LETF provider prospectuses currently calculate annual expected returns for LETFs relative to an underlying index using a range of assumed annualized index returns and standard deviations. For daily rebalanced LETFs, the underlying index geometric daily return is calculated based on Equation (7):

where

RA is the annual return and N is assumed to be 252 for trading days in a year. Using the approximation in Equation (7), the arithmetic mean return (

μt) is found by adding

from Equation (2) where the daily standard deviation is approximated using Equation (4) by solving for

. This is necessary, as the daily arithmetic mean must exceed the daily geometric return to attain the original annual return. The annualized LETF return R

L is then calculated as shown below:

This method replicates tables found in the prospectuses of LETF providers with minor differences of less than 0.1% even at the higher annualized index return and volatility assumptions. The various prospectuses themselves apply Equation (1), which was derived under a continuous time setting that implicitly uses the approximations in Equations (2) and (4). The calculations from Equations (1) or (8) give the same basic results, see (

Direxion Prospectus, 2025;

GraniteShares Prospectus, 2025;

Proshares Prospectus, 2025; or

Tradr Prospectus, 2025) prospectuses, but all LETF fund providers use this method to create their long-run return tables. All the calculations in this study showing the approximation method use the continuous time format in

Cheng and Madhavan (

2009) or

Avellaneda and Zhang (

2010), see

Appendix A for more details.

However, when using the above method, the realized annual return and standard deviation of an underlying index is significantly different from the assumed annual return and standard deviation for the more extreme return/volatility assumptions.

Table 2 shows the assumed underlying index annual return/volatility pairs and the numerical Monte Carlo (100,000 simulations) simulated volatility that is realized. For each simulation, 252 daily returns were created based on the assumed annualized mean and standard deviation drawn from a normal distribution. The cumulative annual return is then calculated, and the average mean and standard deviation of those 100,000 returns is shown in

Table 2.

At low levels of volatility, the numerical results align functionally well with the approximations except for the biased volatility. However, with a standard deviation of 50%, the results begin to significantly deteriorate with higher returns such as the assumed 40%/50% return/volatility pair, which numerically results in a 59% mean return and 84% volatility. It should be noted that the median returns are exact, as they are not affected by the erroneous standard deviations.

However, this is not helpful, as the standard deviation is the primary factor that erodes LETF returns over time relative to an underlying index. With an assumed annual return of 60% and volatility of 100%, the actual mean/volatility pair using the approximation method is 163% and 339%, respectively. Thus, this method’s calculations significantly deviate from using a statistically correct formulation for estimating LETF returns where the deviation will increase with greater leverage, higher absolute return/volatility assumptions, and time.

In summary, the approximation errors by using Equations (2) and (4) are exaggerated for LETFs. Thus, when one poses the question of how would a 3.0× LETF perform over a year when the underlying index experiences a 50% annual return with a 40% standard deviation, the approximation formula should not be used to (1) back out the index daily return and daily standard deviation , then (2) calculate the LETF’s daily return and standard deviation, (3) calculate a geometric return, and finally (4) annualize once again using an approximation formula. The larger the mean and standard deviation assumed, the greater the deviation from the statistically correct value.

3.4. Statistically Exact Formulation for LETF Expected Return

To calculate statistically correct values for LETFs, the exact daily arithmetic mean and standard deviation for the underlying index can be calculated by solving for

and

in Equations (3) and (5) simultaneously for a given annual return

and annual standard deviation

. From Equation (5), the daily variance

can be solved directly, which gives the following:

This value can then be substituted into Equation (3), resulting in Equation (10):

However, there is no closed-form solution for the daily arithmetic index return

, but it can be solved for iteratively until a given assumed

is found. With

identified, Equation (9) can then be used to solve for

. With the statistically correct daily arithmetic mean and daily standard deviation, the annual return for a LETF is given by the following equation:

This is simply Equation (3) with the statistically correct daily mean and standard deviation multiplied by the leverage ratio and then annualized. See

Appendix A for step-by-step details and a numerical example of how this is performed.

It should be noted that the initially assumed annual return will not equal the annualized geometric return since compounded returns are not normally but lognormally distributed. By (1) starting out with an assumed annual mean and standard deviation, then (2) finding the daily arithmetic mean and standard deviation that results in a daily geometric mean (given a daily standard deviation) that can then (3) be annualized to reattain the originally given annual return and standard deviation is not the same as the realized annual mean given volatility around the geometric mean. The daily returns will be normally distributed using the above, but after compounding to reacquire an annualized return results in a lognormal distribution with a realized mean greater than the original.

However, the median will be exactly the original annual return value and thus, armed with the correct standard deviation, an exact estimate of the central tendency for LETFs returns can be made. Theoretical results from Equation (11) are verified using 100,000 Monte Carlo simulations per return/volatility pair.

Specifically, after calculating

and

, annual returns are created using 252 trading days where leverage ratios from −3.0× to 3.0× were applied to the daily returns to calculate the annual returns for the LETFs. Index daily returns were drawn from a normal distribution based on the mean and standard deviation calculated above. A total of 100,000 simulations were run where the initial assumed return and standard deviation for the index was affirmed. As

Table 2 demonstrated earlier, this was not the case when using the approximation method.

Table 3 shows the statistically correct values for a projected 2.0× daily LETF annual return for a given underlying index return and volatility. There is little to no variance around this number if the annual return of the index is ex-post realized given the volatility assumption, (assuming volatility stationarity although this is not critical). The second set of numbers in each row is the statistically correct value minus the corresponding value in

Table 1, which uses the approximation method. These are theoretical returns, and the LETF returns are assumed to be exactly the daily leverage times the underlying index each day. Financing and management costs are ignored but could be easily incorporated by reducing the calculated daily

by an estimate of these costs. The results in

Table 3 show only the cumulative return discrepancy between the daily and realized leverage ratio due to compounding.

Compared to

Table 1, deviations from the approximation method become quite large the higher the assumed annual return and standard deviation. This is especially obvious when comparing the last rows of

Table 1 and

Table 3 with a 50% or greater volatility where the deviation goes from 35.6% in absolute return to 103.2% for the 60%/100% return/volatility assumption.

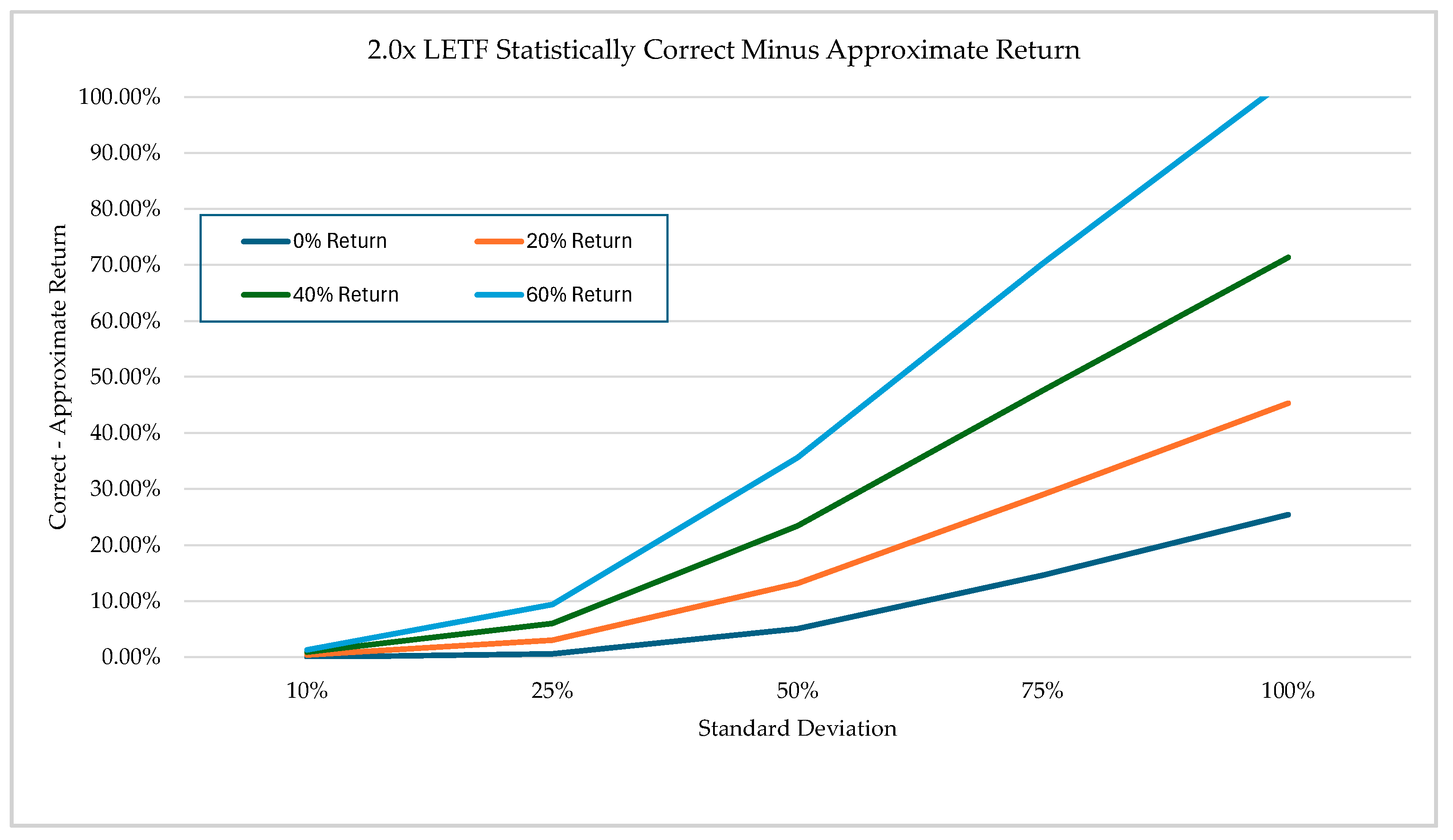

Figure 3 visually shows the difference in absolute returns between the two methods for the 0% to 60% annual return assumptions.

All values in

Table 3 are confirmed using Monte Carlo methods with differences of less than 1.0% even at extremes. Although the calculated daily returns using the approximation or statistically correct method do not substantially differ, it is the use of the approximation formula to calculate the standard deviation which is the culprit for most of the dispersion.

To demonstrate how leverage affects the results,

Table 4 shows the comparison values for a 3.0× using the approximate method (Panel A) vs. the statistically correct method (Panel B). The difference between the two methods becomes large even when assuming a moderate 25% volatility at the higher return levels. Because the approximation method overestimates the daily standard deviation to such an extent with high return assumptions, the expectation using the approximation method at the 60%/75% return/volatility results in a −24.2% return instead of the statistically correct value of 147.6%.

Although not available in the U.S., there is a 5.0× fund on the London Stock Exchange. In addition, fund providers have not given up in offering this type of leverage in the U.S. In fact, nine LETF fund providers have recently been warned to stop plans to issue funds with up to 5.0× leverage (

Tsekova & White, 2025).

Table 5 shows why the SEC may be adamant to not allow these funds to be introduced on U.S. exchanges. However, the approximation model has substantial errors up to more than 300% at high trend/lower volatility levels.

Despite the large differences, outcomes except for the very highest trend/low volatility situations are generally associated with a near or total loss. With that said, regulatory decisions should be made with statistically correct projections and not ones based on an approximation method. Leverage Shares’ SP5Y on the London Stock Exchange did not use the approximation method to create a similar table (

Leverage Shares Prospectus, 2025), as shown above but simulated returns attaining numbers mostly between the approximation and statistically correct model. For their 3.0× funds, they use the approximation method (see

Leverage Shares Prospectus, 2023).

3.5. Statistically Correct Method for Inverse LETF Expected Return

Expected returns for inverse funds are significantly overestimated for yearly periods for declining markets (by over 200% in some cases), but with market trends generally up, long-term holdings of these funds are not advised even for the most bearish investor. One of the issues is that declining markets are generally accompanied by high volatility, which mitigates expected gains from LETFs. Since leverage is required even for −1.0× funds, calculations using the approximation method deviate from statistically correct values even at this level.

Table 6 shows the approximation and statistically correct method for expected −2.0× LETF returns with greater deviations occurring for high negative returns regardless of volatility.

3.6. Statistically Correct Method for Monthly and Quarterly LETF Expected Returns

Using the statistically correct method detailed in this study, daily vs. monthly vs. quarterly calendar LETFs can now be directly compared for any time horizon. For a year, simply set n = 252, 12, or 4, respectively, as this is how often these funds are rebalanced.

Table 7, Panels A and B display the results using the statistically correct method for monthly and quarterly calendar 2.0× LETF with asterisks identifying when the return is greater than the daily LETF’s statistically correct value. For low levels of volatility, the daily LETFs marginally outperform the monthly (see

Table 3 for daily LETF values), but as volatility increases, the monthly LETFs outperform unless the trend is high enough to offset the higher volatility. After 50% volatility, the trend would need to be even higher than 60% to outperform the monthly LETFs.

The same types of results occur for quarterly reset LETFs. For low levels of volatility and high trend, the daily and monthly LETFs outperform, but quarterly LETFs outperform at high volatility levels regardless of the trend, as can be seen in the last two columns. As there are currently no monthly or quarterly reset inverse LETFs, those results are not reported.

Although not shown, using the approximation method results in the calendar monthly 2.0× LETF with a −7.5% return for the 60% annual index return at the 100% volatility level, and the quarterly with only a 2.7% return (see

Tradr Prospectus, 2025). In contrast, the prospectus for a daily 2.0× LETF has an expected −5.8% return. Statistically this is incorrect and implies the illogical conclusion that the daily reset has a higher expected return than the monthly LETF at these trend/volatility levels.

The divergence in returns between daily vs. the longer reset LETFs in

Table 3 and

Table 7 are based solely on compounding effects. High trend and low volatility for bullish funds is advantageous for daily reset LETFs, as increasing values are associated with ever higher levels of absolute leverage. As an example, an underlying index increases from 100 to 103 while a 2.0 LETF starts at

$100 and increases to

$106. The LETF starts with

$200 exposure and then must buy another

$12 of exposure after the increase. In other words, bullish LETFs are the ultimate momentum asset, and their cumulative return relative to the index in this environment will exceed the daily leverage.

In contrast, longer calendar LETFs will keep $200 of exposure until they are reset, effectively reducing their leverage during upward trends until the reset date when the leverage returns to its initial value. This is advantageous if the market is volatile since leverage is effectively reduced when the market increases and rises when the market decreases.

3.7. Empirical Validation

Academic studies and theoretical projections aside, nothing compares to the empirical evidence many of these funds have experienced, with LETFs having eight of the top ten performing funds over the last 10 years even after experiencing severe losses during one crisis or another, see

Table 8. This is not unique for 2025 as LETFs often hold the top spots for 10-year returns. The extraordinary long-term gains for many of these LETFs are hard to ignore, especially for long-term buy-and-hold investors who can stomach losses of 70%+ in short periods of time. As an example, Direxion and ProShares 3.0× S&P 500 is up 1,046% and 1,043%, respectively, relative to SPY (291%) for an effective leverage ratio of 3.6× while Proshare’s 3.0× QQQ is up 2,516% relative to QQQ (511%) for an effective leverage ratio of 4.9×. The top performing fund is a 2.0× semi-conductor fund up 6,805%.

Caution is obviously warranted, as outsized returns are accompanied by outsized risk. USD, TECL, and SOXL all lost 68% in the first seven months of 2022 and over 40% of their value in under a month during July/August of 2024. Thus, investors need to be wary of highly leveraged funds, even more so for those that are narrow in focus.

To assess the application of the two methods, ProShares USD latest one-year return ending 2025, October 31 was 90.4%, while the DJ U.S. Semi-conductor index increased by 58.4%. Assuming zero costs, a perfect daily 2.0× LETF should have earned 108.2%. The differences are trading costs, financing costs, expense ratio, and tracking error. The index’s daily return and standard deviation were 0.22% and 2.72%, respectively, over this year and based on statistically exact annualization, an annual standard deviation of 78.7% is calculated, reaffirmed using Monte Carlo simulation as described earlier in this study.

Table 9 shows the approximation method using 58.4%/78.7% return/volatility inputs predict the annual return for the 2.0× LETF to be 35% while the statistically correct method predicts 109.8%, almost exactly the result from a perfect 2.0× daily return over this period. For the inverse −2.0×, the approximation method calculates a −93.9% loss while the statistically correct method calculates −77.5%, which is exactly what occurred both for a perfect daily −2.0× (−77.5%) and what ProShares (−71.4%) basically provided.

The year ending 31 October 2024 tells the same story while the next column uses the year ending 29 December 2022 when the index was down 39.43%. Results are as expected, where the approximation method significantly deviates from both the statistically correct method and the empirical results, while the latter two align almost perfectly. In this case, the approximation significantly overestimates (projected 100.1%) to what a perfect −2.0× attains (46.8%).

To examine how well the methods work during non-stationary volatility regimes as both methods assume stationary volatility, the annual period ending 31 December 2020 is examined, which includes the Covid-Crash, where the underlying index fell over 60% in less than a month. Over the year, the daily standard deviation varied from 1.1% to 7.9% (28% to 317% annualized using statistically correct methods) based on a 21-day moving average and averaged 2.97% (80.4% annualized). For context, the S&P 500 has only ranged from 0.22% to 6.07% (annualized 3.9% to 139%) over any 21-day period since 1990. The approximation method continues to understate the return by more than 50 percentage points, but the statistically correct method overstates by 5.6%, (70.9% vs. 65.3%). Thus, even with extreme violations of the stationarity variance assumption, the statistically correct method is relatively robust. For bullish funds, this error would increase the greater the leverage.

For 5.0× funds, it is not beyond the possibility of a total loss in a day given the S&P fell 22% on 19 October 1987, and even with the market circuit breakers implemented after that date, trading is only halted completely for the day with a 20% decline. Regardless of the average volatility over any time frame encompassing such a loss, the fund is at a total loss although some providers may hold deep out of the money put options to avoid such a scenario.

For monthly and quarterly calendar 2.0× LETFs, this is an even bigger issue, as they must guard against a 50% underlying asset decline over a longer time frame. To avoid 100% loss scenarios, Tradr’s calendar LETFs have 35% decline triggers in place where 2.0× calendar LETFs will reset the leverage back to 2.0× rather than waiting until the end of the period. In this way, a total loss can be avoided. Thus, although both the LETF return projection methods assume normality with a constant variance, extreme deviations from this assumption can lead to some error. This was demonstrated in 2020, although the error is by a magnitude smaller for the statistically correct method. In addition, extreme returns in the opposite direction of the leverage can also cause prediction error due to major losses LETFs would realize.

As a final note and in defense of the approximation method, it does work quite well ex-post. If one inputs the realized daily average return and daily standard deviation in Equation (8), the predicted LETF returns are quite accurate for extended holding periods. The error occurs when one uses an assumed annual return and standard deviation and attempts to predict what would occur with those inputs.

4. Discussion

The substantial gap found in this study between the theoretically correct expected return estimates and those produced by an approximation model currently in use by fund providers results in overly negative estimates for bullish leveraged funds in high-return, high-volatility environments and overly optimistic results for bearish funds in low-volatility, low return environments.

These differences fundamentally alter portfolio optimization involving leveraged products, as these products are now being used by institutional investors including investment advisors and bank trusts,

Choi and Kahraman (

2021). Using underestimated expected returns would systematically underweight or exclude leveraged ETFs in portfolio formations. Demonstrating the practical significance of projecting LETF expected returns accurately,

Glenn (

2021) showed a combination of a 3.0× equity LETF and a 3.0× treasury LETF achieved a 45% annualized return over 10 years while mitigating drawdowns to less than 25%.

Smirnov (

2021) had similar findings showing the use of LETFs could extend typical 60/40 portfolios resulting in higher returns and reduced drawdowns.

Results in this study also have implications for tactical trading strategies as the approximation model underestimates returns in trending markets suggesting momentum strategies implemented with LETFs could be effective. Even in volatile markets such as experienced by semiconductors, the statistically correct method shows that LETFs can be successfully held long-term if the return trend is high enough. The approximation method shows negative returns in these circumstances, which are neither correct theoretically nor empirically.

The regulatory landscape also warrants reconsideration. The Security and Exchange Commission’s Rule 18f-4 capping new leveraged ETFs to 2.0× creates competitive moats for grandfathered higher leveraged funds and possible substitution to higher leveraged ETNs, which carry credit risk. This is an ongoing battle, as the SEC sent warning letters in December 2025 to nine LETF providers planning on new funds with up to 5.0× leverage, (

Tsekova & White, 2025). Regulators have emphasized short-term trading suitability partially supported by tables derived from approximation methods that understate long-term holding benefits for bullish LETFs in highly trending markets. Multiple studies including this one have shown LETFs can be successfully held for extended periods expanding to years not days in the right circumstances and within the right framework.

Rather than concentrating on minimizing leverage, regulators may want to consider additional disclosure requirements such as presenting return scenarios over longer periods of time during bullish, bearish, and more volatile markets. The 10-year historical returns and the possibility of returns ranging from disastrous to phenomenal are ignored. The “daily trading” warnings lack context. Additional investor training from both FINRA and the SEC could acknowledge how LETFS can be used both for increasing and decreasing risk. For advisors using LETFs, a certification requirement could be created to ensure proper understanding of these instruments.

Meanwhile, higher leveraged funds continue outside the United States. Most relevant to this is how large the error is using the approximation model for 5.0× LETFs. Results using the approximation method show virtually 100% losses at the 75% volatility level even under 60% annualized returns for a 5.0×. The statistically correct model has the exact opposite with a 100% return. At the 60%/50% return/volatility level, the statistically correct model projects a 350% return vs. −13.7% return. This type of erroneous calculation is not conducive for optimal oversight and may have had a role in capping leverage and the recent warning letters from the SEC.

Although higher leverage is riskier, in the right types of markets it can and has delivered superior risk-adjusted returns. In addition, studies such as

Scott and Watson (

2013),

Trainor et al. (

2020), and

Glenn (

2021) showed how they can be used to reduce as opposed to increase risk while maintaining typical non-leveraged portfolio type returns.

In terms of future research, an extension of this study’s model could incorporate expense ratios and financing costs. The latter could be particularly problematic in the era of higher interest rates and swap costs, especially for the riskier type LETFs on single stocks and bitcoin. In addition, there are 5.0× international funds.

Table 4 and

Table 5 in this study show the error between the approximation and statistically correct formulation becomes larger the higher the leverage. Is there an optimal leverage? Studies such as

Ott and Zimmer (

2016) have attempted to answer this question, arriving at approximately 1.8 as optimal using a theoretical model which applied the same type of approximation method shown in this study. They also found the historical optimal which was slightly lower, while

Miller et al. (

2021) using Monte Carlo simulation found similar optimal leverage ratios of 1.7×. The statistically correct model derived in this study can help further this area of research.

An additional problem with both the approximation and statistically correct model is the assumption of a stationary variance. The higher the leverage, the bigger this problem will be. As an example,

Table 9 shows the statistically correct method overestimates a perfect theoretical daily Semi-conductor 2.0× LETF by 5.6%. A 5.0× fund would have overestimated this by 12.6% (−52.1% vs. −64.7%). This issue is even larger using the approximation method. Investing in 5.0× funds long term is not attractive, especially with the index up 44% during this period. This highlights the fact that at some point, the compounding decay with extreme leverage is difficult to overcome. Both these avenues are areas for future research.

For the individual investor, practical implications of this research show LETFs can be held for relatively longer periods of time than current prospectuses suggest. However, investors should understand the different types of markets in which LETFs excel (trending) versus quick decay (mean reverting or volatile environments). Risk tolerances need to be addressed before investing, not after as large drawdowns can occur suddenly. Rebalancing and time horizons need to be considered. LETFs can be held successfully for long-term horizons but they are more for the buy-and-monitor investor instead of buy-and-hold, as their percentage of an investment portfolio can swell or diminish to a much greater extent than typical non-leveraged assets.

5. Conclusions

This study addresses how approximation methods currently used by fund providers to generate prospectus tables systematically underestimate expected returns for bullish leveraged ETFs by over 100 percentage points annually in high-return/high-volatility environments. Conversely, these methods overstate expected performance for bearish leveraged products during low-return/low-volatility conditions by similar magnitudes. These errors are magnified with higher leverage.

A statistically correct method, validated through both Monte Carlo simulation and empirical examples, is derived. The fact that the majority of the top ten performing ETFs over decade long holding periods is not an anomaly. It is a predictable outcome of favorable compounding in trending markets overcoming typical volatility decay that approximation methods do not fully capture.

The implications of this research extend from portfolio management to risk assessment. Accurate projected return estimates are essential for portfolio managers and institutional investors who are increasing their use of these products, (

Glenn, 2021). Underestimating returns leads to systematic errors for portfolio weighting schemes, optimization, and asset allocation.

This is particularly relevant as new monthly and quarterly reset calendar LETFs (the latter two recently introduced in 2024) have been introduced to the market recognizing investor holding periods extend well beyond daily holding periods. Expected return results using the statistically correct model show the longer reset LETFs outperform during periods of average to high volatility and daily LETFs will outperform in periods of high trend and low volatility. This is counter to what could be inferred using approximation methods to project returns for this type of LETF.

There are caveats to this study’s findings. Improved expected return estimates do not change the extreme drawdowns LETFs can experience in a very short period such as triple leveraged TQQQ’s 70% loss from 19 February 2020, to 20 March 2020, during the Covid crash. Despite this loss, it is still in the top ten for ten-year cumulative returns. This study does not account for expense ratios, management costs, or tax considerations, which erode theoretical benefits.

Ultimately, leveraged ETFs are complex instruments whose suitability depends on market regime, investor sophistication, risk capacity, and portfolio context. They can be used to increase and perhaps even decrease risk exposure. For those seeking to hold these assets over extended periods, they should be monitored, as their weight in a broader portfolio can change dramatically relative to traditional non-leveraged assets. This study is not meant to advocate for or against LETFs on whether they are used for short-term tactical moves or over extended holding periods within a broader portfolio. Decisions about LETFs should rest on computationally correct derivations so as not to distort either returns or the risk associated with their returns. This study provides an improved framework for projecting LETF returns relative to an underlying index to aid decision-making by investors, advisors, fund sponsors, and regulators.