1. Introduction

Exchange rates occupy a central position in the global economic system, acting as key adjustment mechanisms through which macroeconomic and financial shocks are transmitted across countries. Beyond their nominal valuation, exchange rates encapsulate the complex interaction between international trade, capital mobility, and monetary policy decisions. Traditional theoretical frameworks, notably the Mundell–Fleming model, explain exchange rate movements primarily through macroeconomic fundamentals such as interest rate differentials, inflation dynamics, and productivity developments (

Mundell, 1963;

Fleming, 1962). While these factors remain relevant, they have become increasingly insufficient to account for the magnitude, persistence, and volatility of exchange rate movements observed over recent decades.

Since the early 2000s and more markedly following the global financial crisis geopolitical risk has emerged as a major driver of uncertainty in international financial markets. A succession of global disruptions, including the European sovereign debt crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the Russia–Ukraine conflict, has demonstrated that geopolitical tensions extend well beyond political boundaries. These events reshape investor expectations, amplify global risk aversion, and induce abrupt reallocations of capital across countries and asset classes. As a consequence, exchange rates respond not only to domestic economic conditions but also to shifts in global uncertainty and investor sentiment. Empirical evidence consistently shows that safe-haven currencies, such as the U.S. dollar, the Swiss franc, and the Japanese yen, tend to appreciate during periods of heightened geopolitical stress, whereas currencies of emerging, trade-dependent, or commodity-importing economies are more likely to depreciate under similar conditions.

Despite the growing recognition of these mechanisms, much of the empirical literature continues to rely on modeling frameworks that implicitly assume stable and time-invariant relationships between exchange rates and their determinants. However, the repeated occurrence of global crises since 2008 suggests that the transmission of geopolitical shocks is inherently nonlinear, asymmetric, and state-dependent. Exchange rate sensitivity to geopolitical risk is likely to evolve over time and to differ markedly across countries, depending on factors such as institutional credibility, financial openness, energy dependence, and the degree of monetary policy autonomy. In this context, static econometric models are ill-suited to capture the dynamic and regime-dependent nature of exchange rate responses to geopolitical uncertainty.

To address these limitations, this study adopts a Bayesian Time-Varying Parameter Vector Autoregressive (TVP-VAR) model with stochastic volatility, building on the methodological contributions of

Primiceri (

2005) and

Koop and Korobilis (

2013). This flexible framework allows both the transmission coefficients and the volatility of shocks to evolve endogenously over time, making it particularly appropriate for analyzing exchange rate dynamics in environments characterized by structural breaks and recurrent geopolitical disturbances. The empirical analysis focuses on a sample of 17 OECD economies over the period 2010–2025, a timeframe that encompasses multiple episodes of global turmoil and elevated geopolitical uncertainty.

Although most OECD countries are not directly involved in armed conflicts, their exchange rates remain highly exposed to geopolitical risk through a range of indirect transmission channels. These include fluctuations in energy and commodity prices, financial-market spillovers, cross-border capital flows, and disruptions in global value chains. Given their high degree of trade openness and financial integration, OECD economies constitute a relevant and informative setting for examining how geopolitical shocks propagate internationally and affect currency markets, even in the absence of direct conflict exposure.

The analysis further accounts for structural heterogeneity by explicitly considering differences in exchange rate regimes across countries, distinguishing between free-floating currencies, managed floating regimes, and economies operating within integrated monetary frameworks. This classification is used to interpret impulse-response dynamics and time-varying coefficients, allowing the study to identify regime-dependent adjustment mechanisms and differences in shock absorption capacity.

Against this background, the study is guided by three central hypotheses. First, geopolitical risk shocks are expected to exert a statistically significant influence on exchange rate dynamics against the U.S. dollar across OECD economies. Second, the magnitude and persistence of these responses are hypothesized to be heterogeneous, reflecting cross-country differences in institutional quality, financial openness, and external vulnerability. Third, safe-haven and energy-exporting economies are expected to display more muted or stabilizing exchange rate responses to geopolitical shocks, whereas emerging and externally dependent economies are likely to experience stronger and more persistent depreciations.

By testing these hypotheses within a Bayesian TVP-VAR framework, this research aims to provide a deeper and more realistic understanding of how geopolitical uncertainty is transmitted to exchange rate markets. In doing so, it contributes to the literature by highlighting the time-varying, asymmetric, and regime-dependent nature of exchange rate responses in an increasingly uncertain and geopolitically fragmented global environment.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews the related literature on exchange rate dynamics and geopolitical risk.

Section 3 describes the data and presents the econometric methodology, including the Bayesian TVP-VAR framework with stochastic volatility.

Section 4 reports and discusses the empirical results, focusing on impulse-response functions and time-varying coefficients.

Section 5 concludes and outlines key policy implications and directions for future research.

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Data

The empirical analysis is based on monthly data covering the period from January 2010 to June 2025, which provides a sufficiently long horizon to capture several episodes of major geopolitical and economic instability.

The study focuses on two fundamental variables.

The first is the Geopolitical Risk Index for High-Conflict Countries (GPRHC) developed by

Caldara and Iacoviello (

2018). This indicator quantifies the level of country-specific geopolitical risk based on the frequency of newspaper articles referring to wars, terrorist threats, and diplomatic crises in high-conflict regions. The index provides a precise and high-frequency measure of geopolitical uncertainty, enabling the detection of periods of heightened tension that may affect currency behavior.

The second variable is the bilateral exchange rate against the U.S. dollar, which serves as the benchmark and primary anchor currency in the global financial system. All exchange rate series are obtained from The Global Economy database.

The sample includes 17 OECD countries representing a diverse set of economic structures and exposure levels to geopolitical shocks: Australia (AUS), Canada (CAN), Switzerland (CHE), Chile (CHL), Colombia (COL), Denmark (DNK), France (FRA), the United Kingdom (GBR), Hungary (HUN), Japan (JPN), South Korea (KOR), Mexico (MEX), Norway (NOR), Poland (POL), Sweden (SWE), Turkey (TUR), and the United States (USA). These countries were selected for their advanced financial systems, trade openness, and institutional comparability, while exhibiting different energy dependencies and geopolitical sensitivities. This diversity allows for a meaningful cross-country comparison of exchange rate responses to specific geopolitical shocks.

3.2. Methodology

The empirical strategy is designed to capture both the short-run dynamics and the time-varying effects of geopolitical risk on exchange-rate movements across OECD economies. The analysis proceeds in a structured sequence combining preliminary statistical diagnostics with dynamic econometric modeling.

As a first step, descriptive statistics are computed to characterize the distributional properties of the exchange rate returns (EXCH) and the geopolitical risk index (GPRHC). To assess the stochastic properties of the series, Augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) unit-root tests are conducted for each variable and country. The ADF test is implemented under the following hypotheses:

- -

H0: the series contains a unit root and is non-stationary;

- -

H1: the series is stationary.

The results of the ADF tests indicate that exchange-rate returns and geopolitical risk indices are stationary in levels for the vast majority of countries, with only marginal exceptions becoming stationary after first differencing. Given this predominance of I(0) processes, the variables are modeled directly in levels, without differencing, thereby preserving their short-term dynamics and avoiding unnecessary transformations.

Since cointegration analysis requires variables to be integrated of order one, the stationarity of the series implies that long-run cointegration testing is not econometrically required in the present context. Consequently, no inference regarding long-run cointegrating relationships is pursued, and the empirical focus is placed on modeling dynamic interactions rather than long-run equilibria. This methodological choice ensures full consistency between the time-series properties of the data and the econometric specification.

As an initial benchmark, a country-specific bivariate Vector Autoregressive (VAR) model is estimated in levels to capture short-run interactions between exchange rates and geopolitical risk. The VAR framework provides a useful reference for examining basic dynamic responses. However, standard VAR models impose constant parameters and Gaussian innovations, assumptions that are not supported by the data. Diagnostic tests based on the Jarque–Bera statistic reveal pronounced non-normality, asymmetry, and heavy-tailed behavior in the residuals, indicating the presence of structural instability and time-varying volatility.

To address these limitations, the core empirical analysis relies on a Bayesian Time-Varying Parameter Vector Autoregressive model with Stochastic Volatility (TVP-VAR-SV). This framework allows both the transmission coefficients and the volatility of shocks to evolve endogenously over time, capturing nonlinear, asymmetric, and regime-dependent responses to geopolitical risk. In order to accommodate the heavy-tailed nature of the innovations, the stochastic-volatility disturbances are modeled using a student-t distribution rather than a Gaussian specification. This choice improves the robustness of posterior inference and reduces the risk of underestimating extreme geopolitical shocks.

Overall, this combined approach provides a flexible and statistically coherent framework for analyzing exchange-rate dynamics in an environment characterized by recurrent crises, shifting risk perceptions, and evolving geopolitical tensions. By focusing on time-varying interactions rather than long-run equilibrium relationships, the methodology is well suited to capturing the dynamic and state-dependent nature of geopolitical risk transmission to currency markets.

3.2.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 reports the descriptive statistics for the monthly returns of exchange rates (EXCH) and the specific geopolitical risk index (GPRHC). Overall, the results reveal pronounced cross-country heterogeneity, reflecting structural differences in macroeconomic stability, exchange rate regimes, and exposure to geopolitical shocks.

The mean exchange rate returns are generally close to zero for most countries, ranging between (−0.0003) for Switzerland (CHE) and (0.0187) for Turkey (TUR). In contrast, the mean values of the geopolitical risk index (GPRHC) remain positive across nearly all countries, with relatively high averages observed in Australia (0.51), the United Kingdom (0.46), and Sweden (0.43), suggesting that these economies are more exposed to global geopolitical tensions.

The volatility patterns, as captured by the standard deviation, show substantial variation between economies. Exchange rate volatility ranges from 0.016 (Canada) to 0.043 (Turkey), confirming that emerging or partially liberalized markets such as Turkey and Mexico experience higher fluctuations than advanced economies like Canada, Denmark, or France. Similarly, the volatility of the GPRHC index is particularly elevated in France (2.09), the United Kingdom (5.21), and the United States (2.20), indicating a high degree of variability in geopolitical uncertainty over time.

The skewness and kurtosis coefficients confirm the non-normality of the series. Exchange rate returns generally exhibit slight positive skewness and moderate leptokurtosis, consistent with the stylized facts of financial time series that often display asymmetric and leptokurtic distributions. By contrast, the GPRHC series show extreme leptokurtosis in several countries for instance, France (168), the United Kingdom (177), and the United States (177) highlighting the presence of rare but intense spikes in geopolitical uncertainty. These extreme values reflect the episodic nature of major geopolitical events, which generate abrupt yet powerful disturbances in financial markets.

The Jarque–Bera normality test rejects the null hypothesis of normal distribution for nearly all series at the 1% significance level (p < 0.01), both for exchange rate returns and geopolitical risk indices. This evidence, combined with the observed volatility clustering and asymmetry, suggests that linear and homoscedastic models would be ill-suited for capturing the dynamics between the two variables.

In summary, the descriptive evidence indicates that both the exchange rate and geopolitical risk series are characterized by non-normal distributions, high volatility, and structural asymmetries. These statistical features validate the empirical strategy adopted in this study, confirming the relevance of a Bayesian TVP-VAR framework to analyze the dynamic, time-varying, and heterogeneous linkages between geopolitical risk and exchange rate.

3.2.2. Stationarity Test: Augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF)

Table 2 reports the results of the Augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) unit root tests used to assess the stationarity properties of the exchange rate returns (EXCH) and the geopolitical risk index (GPRHC) for the 17 OECD economies over the period 2010–2025. The tests are conducted in both levels and first differences in order to determine the order of integration of each series.

The empirical evidence indicates that, for the overwhelming majority of countries, the ADF test statistics are highly significant, with p-values close to zero. These results lead to a clear rejection of the null hypothesis of a unit root, suggesting that both exchange rate returns and geopolitical risk series are stationary in levels. This finding implies that the variables exhibit mean-reverting behavior and do not follow persistent stochastic trends over time.

In a limited number of cases most notably for the United Kingdom and the United States the geopolitical risk index appears to display weak persistence at conventional significance levels when expressed in levels. However, these series become stationary after first differencing, indicating an integration order of one. Such behavior is consistent with the nature of geopolitical risk indicators, which may display temporary low-frequency persistence due to prolonged episodes of geopolitical tension rather than permanent stochastic trends.

From a methodological perspective, the predominance of stationary processes has important implications. First, it confirms that the variables can be directly incorporated into a multivariate dynamic framework without the risk of spurious regression. Second, since the variables are stationary in levels for most countries, long-run cointegration analysis is not required. Instead, the empirical strategy focuses on modeling short- and medium-term dynamics through a Vector Autoregressive (VAR) framework and its Bayesian time-varying extension.

The use of a Bayesian Time-Varying Parameter VAR (TVP-VAR) model is particularly appropriate in this context. Although the variables are stationary, their relationships are likely to evolve over time due to structural changes, crisis episodes, and shifts in global uncertainty. The TVP-VAR framework accommodates such time-varying interactions by allowing coefficients and shock transmission mechanisms to change endogenously, without imposing a fixed long-run equilibrium structure.

From an economic standpoint, the stationarity of exchange rate returns and geopolitical risk implies that the effects of geopolitical shocks are transitory rather than explosive. While geopolitical events such as wars, pandemics, or energy crises can generate sharp and abrupt exchange rate movements, these effects tend to dissipate as markets gradually adjust and uncertainty subsides. This behavior reflects the adaptive nature of foreign exchange markets and the capacity of OECD economies to absorb external shocks through flexible prices, policy responses, and financial adjustments.

Overall, the ADF test results confirm that the exchange rate and geopolitical risk series are suitable for dynamic time-varying analysis. The absence of unit roots supports the econometric validity of the Bayesian TVP-VAR framework and ensures that the estimated relationships between geopolitical risk and exchange rate dynamics are both statistically sound and economically interpretable.

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Var-Bivariate Estimate

To analyze the dynamic interaction between exchange rates and geopolitical risk, we estimate a VAR model, the results of which are shown in

Table 3.

The estimation results of the Vector Autoregressive (VAR) model provide preliminary evidence on the short-run dynamics between bilateral exchange rate returns (EXCH) and the geopolitical risk index (GPRHC) across the OECD economies considered. As a benchmark specification, the VAR model is intended to capture basic dynamic interactions prior to the implementation of the more flexible time-varying framework.

The coefficients associated with the lagged exchange rate variable, EXCH (−1), are positive and statistically significant across almost all countries. This finding indicates a pronounced degree of short-run persistence in exchange rate movements, suggesting that past currency fluctuations continue to influence current dynamics. Such persistence reflects the gradual adjustment of foreign exchange markets, where information is incorporated progressively and exchange rates respond with inertia rather than instantaneously.

By contrast, the estimated coefficients of the lagged geopolitical risk variable, GPRHC (−1), are generally small in magnitude and statistically insignificant for most countries. This result suggests that, within a constant-parameter VAR framework, the average short-run effect of geopolitical risk on exchange rates is relatively weak and heterogeneous. Only in a limited number of cases—most notably the United Kingdom—does geopolitical risk appear to exert a statistically significant influence on exchange rate dynamics at conventional significance levels. The mixed signs of the coefficients further point to cross-country heterogeneity in how geopolitical uncertainty is transmitted to currency markets.

The modest explanatory power of the VAR equations, as reflected by the R2 values, is consistent with the nature of monthly exchange rate data, which are influenced by a broad set of macroeconomic, financial, and geopolitical factors. While the VAR model captures some degree of short-term dependence, it is not designed to fully account for structural changes, regime shifts, or nonlinear responses associated with major geopolitical events.

Overall, the VAR results should be interpreted as indicative rather than conclusive. They highlight the presence of exchange rate persistence and suggest that the impact of geopolitical risk may vary across countries, but they also underscore the limitations of constant-parameter models in capturing the dynamic effects of geopolitical uncertainty. These limitations motivate the use of the Bayesian TVP-VAR framework in the subsequent analysis, which allows for time-varying transmission mechanisms and provides a more accurate assessment of how exchange rates respond to geopolitical shocks over different economic and political regimes.

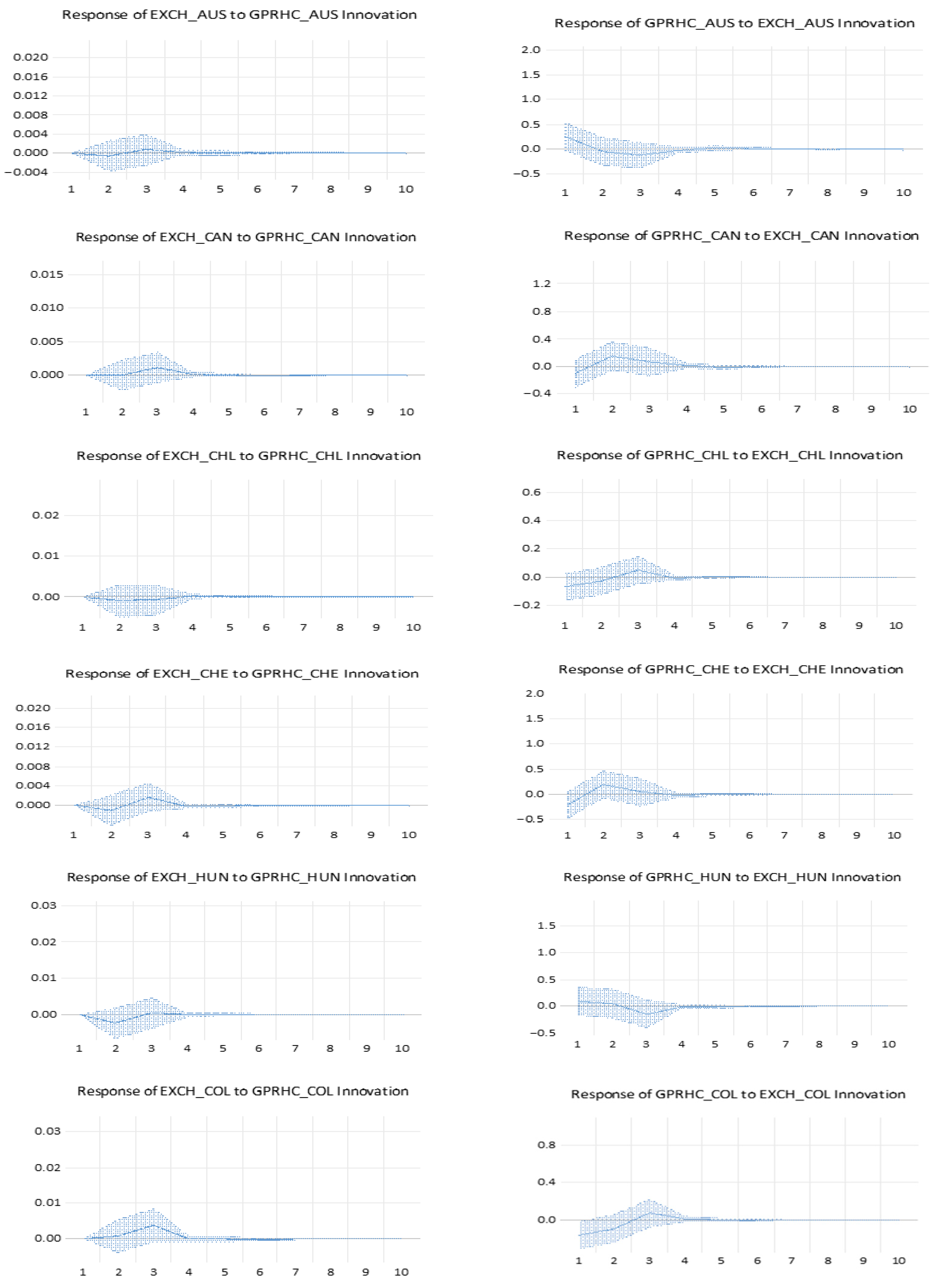

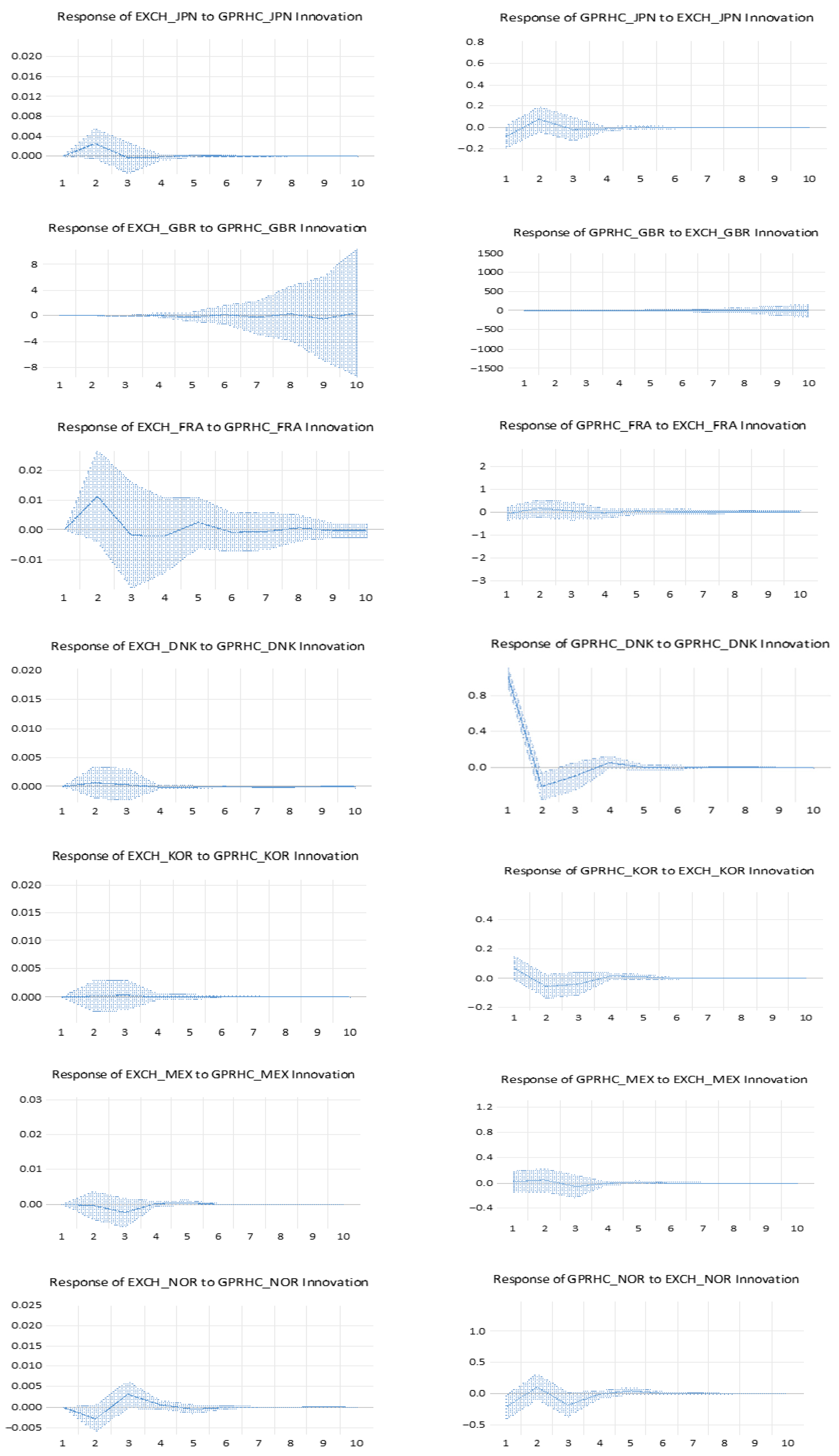

The

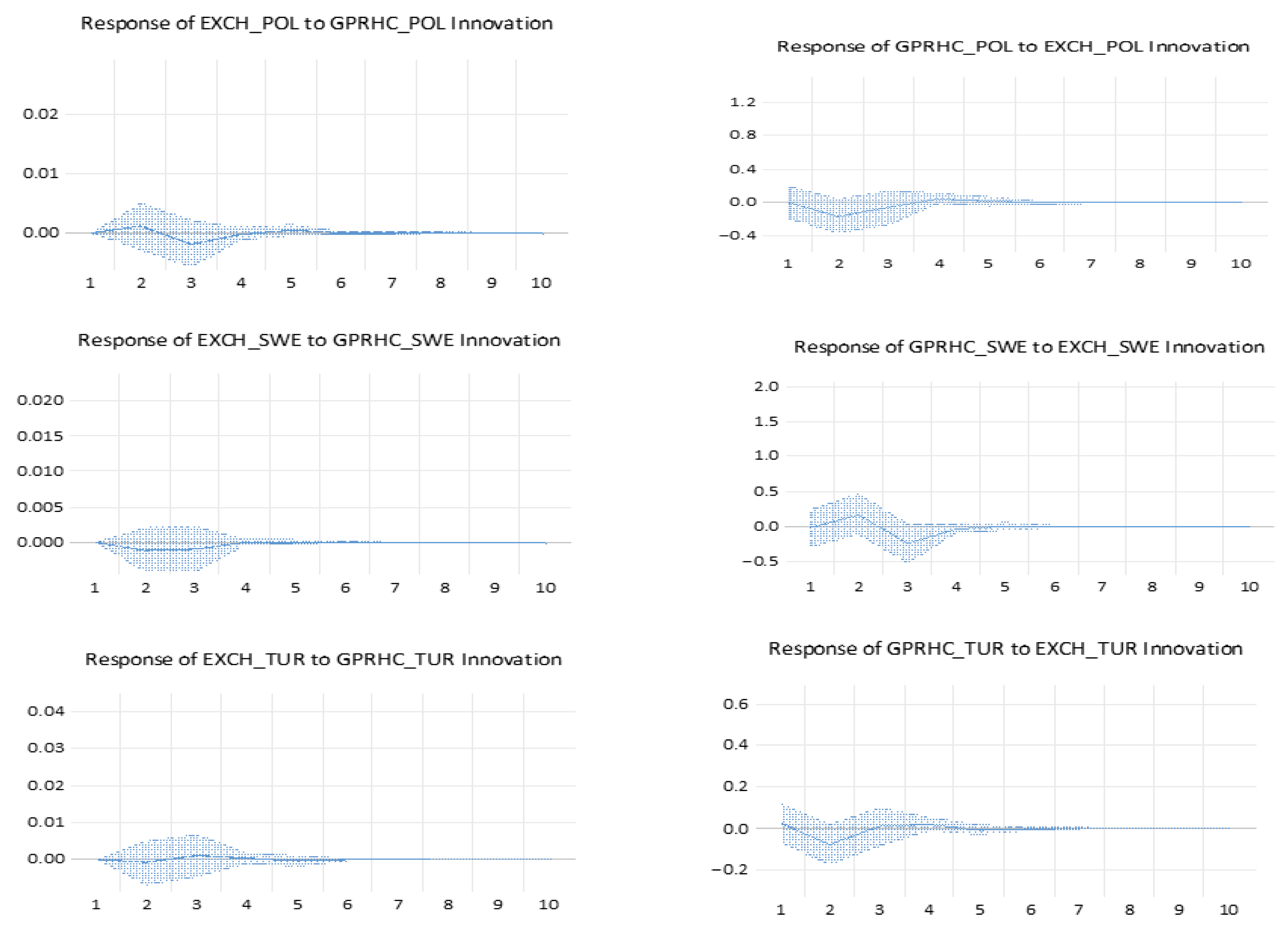

Figure 1 reports that Impulse Response Functions (IRF).

For clarity, the OECD sample is classified into three broad groups. Safe-haven economies include Switzerland and Japan, whose currencies traditionally attract capital flows during periods of heightened geopolitical uncertainty. Energy-exporting economies comprise Australia, Canada, and Norway, where exchange-rate dynamics are partly shaped by commodity-price and terms-of-trade effects. In contrast, energy-importing or trade-dependent economies include Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Hungary, Turkey, and South Korea, which tend to exhibit greater sensitivity to global risk aversion and external financial conditions.

The impulse-response analysis constitutes a core element of our empirical investigation, as it traces how bilateral exchange rates adjust following an unexpected increase in geopolitical risk across OECD economies. By examining dynamic response paths after a one-standard-deviation shock, the IRFs provide a transparent benchmark for comparing short- to medium-run adjustment mechanisms across countries and for highlighting structural heterogeneity related to financial depth, commodity exposure, external vulnerability, and safe-haven characteristics.

Importantly, statistical inference is drawn with caution: in several cases, confidence bands overlap zero over part (or all) of the forecast horizon, implying that some responses may not be statistically distinguishable from zero at conventional significance levels despite appearing economically meaningful. A first group of economies Australia and Canada exhibits contained and rapidly stabilizing responses to geopolitical shocks. Following the shock, these commodity-exporting countries display a brief appreciation episode that is consistent with commodity and terms-of-trade channels during periods of elevated global uncertainty. The responses, however, fade quickly and converge back toward the baseline, indicating strong short-run mean reversion and suggesting that flexible exchange rates, supported by credible macro-financial frameworks, can absorb external disturbances without persistent misalignment. Switzerland and Japan show response profiles consistent with their established safe-haven status. Their currencies tend to appreciate after geopolitical shocks, reflecting flight-to-quality dynamics and global portfolio rebalancing toward low-risk assets. While the adjustment paths are generally smoother and may appear more persistent than in other economies, the strength and statistical relevance of these responses should be evaluated in light of the confidence intervals, which may include zero at certain horizons. A more pronounced and, in some cases, more volatile response is observed in Chile, Colombia, and Mexico, where exchange rates tend to depreciate immediately following a rise in geopolitical risk. These economies share characteristics frequently associated with higher sensitivity to global risk appetite and external financing conditions. As a result, heightened geopolitical uncertainty may induce capital outflows, increase risk premia, and weaken currencies against the U.S. dollar. Nevertheless, the impulse responses typically weaken over the forecast horizon, suggesting that the initial impact is partly absorbed through market adjustment, policy reactions, and external-account mechanisms. For European economies such as Denmark, France, and Sweden, the responses are moderate and generally short-lived.

Deviations from the baseline often dissipate within a few periods, consistent with the stabilizing role of strong institutions, deep financial markets, and policy credibility. In France, where a mild depreciation can emerge after a geopolitical shock, the subsequent reversion toward the baseline indicates limited persistence and suggests that the exchange rate adjusts relatively quickly as uncertainty effects dissipate. Norway and Poland display more complex adjustment profiles, with responses that may change sign across horizons. In Norway, the initial reaction can reflect the interaction between safe-asset demand and energy-export dynamics, whereas in Poland the response may be shaped by regional uncertainty exposure and sensitivity to external financial conditions. The observed oscillations underline that the net exchange-rate effect of geopolitical shocks may reflect competing channels whose relative importance differs across economies and may vary across horizons. Among the most vulnerable economies, Hungary and Turkey tend to exhibit larger depreciations after geopolitical shocks. These dynamics are consistent with higher perceived risk, external financing needs, and greater exposure to shifts in global risk appetite. The extent of persistence, however, should be interpreted carefully given that confidence bands may overlap zero at certain horizons and that constant-parameter IRFs may not fully capture evolving transmission mechanisms during major crisis episodes.

Finally, South Korea and the United Kingdom exhibit distinct response patterns. South Korea may experience a short-lived depreciation consistent with exposure to regional security risks and global supply-chain disruptions, whereas the United Kingdom shows comparatively muted and rapidly reversible responses, reflecting the depth and liquidity of its financial markets and the capacity of the exchange rate to adjust promptly to changes in global conditions.

Overall, the IRFs share a broadly similar qualitative structure across countries: an initial deviation from the baseline followed by gradual convergence back toward it. This pattern indicates that geopolitical shocks primarily generate transitory exchange-rate adjustments rather than permanent shifts in currency behavior. At the same time, the substantial cross-country heterogeneity in magnitude, persistence, and occasionally the sign of the response highlights the limits of constant-parameter models and motivates the subsequent use of a time-varying framework. In particular, a Bayesian TVP-VAR approach is well suited to capturing regime-dependent and time-varying transmission channels that may be masked in average impulse-response estimates over a long sample period such as 2010–2025.

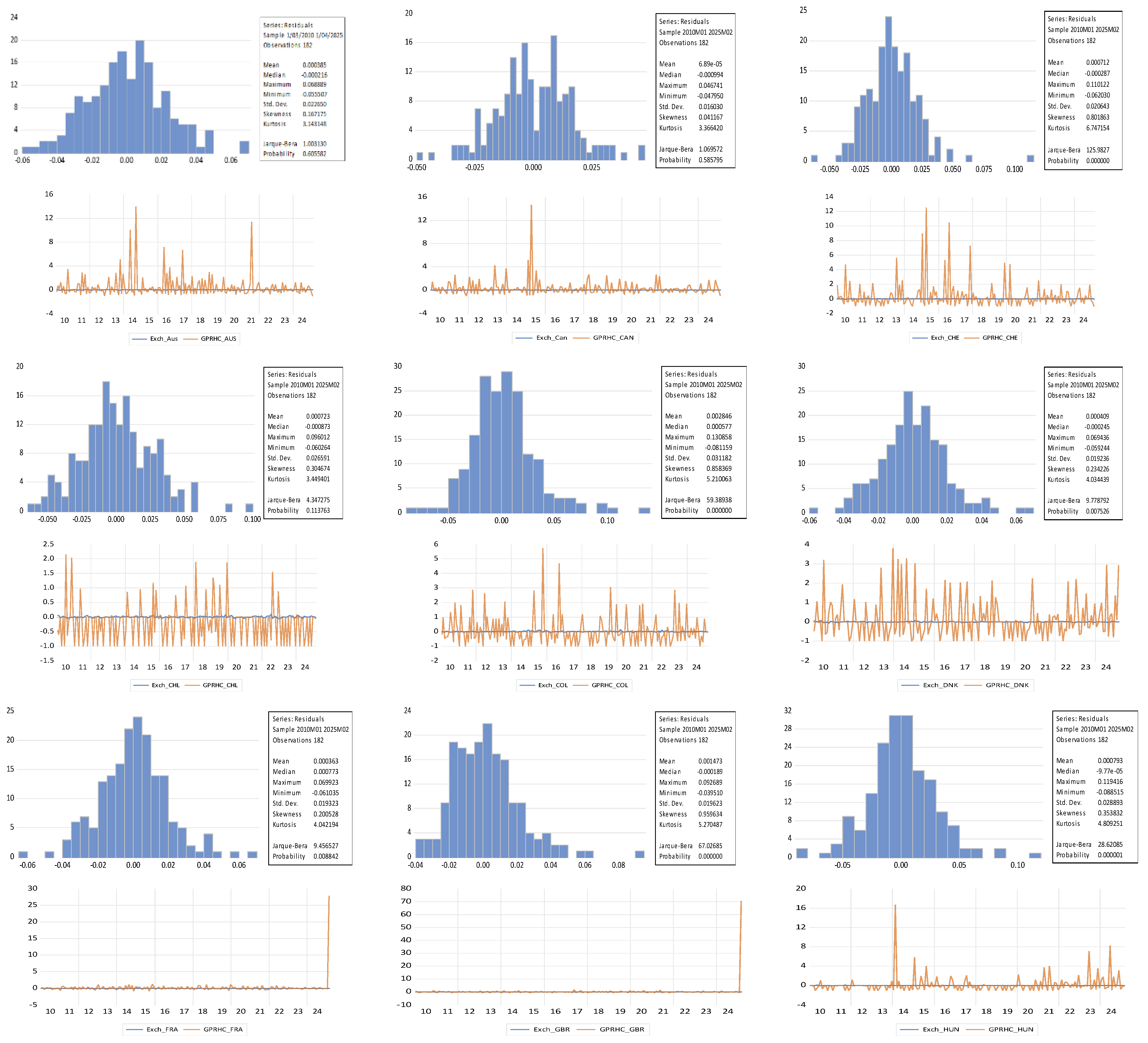

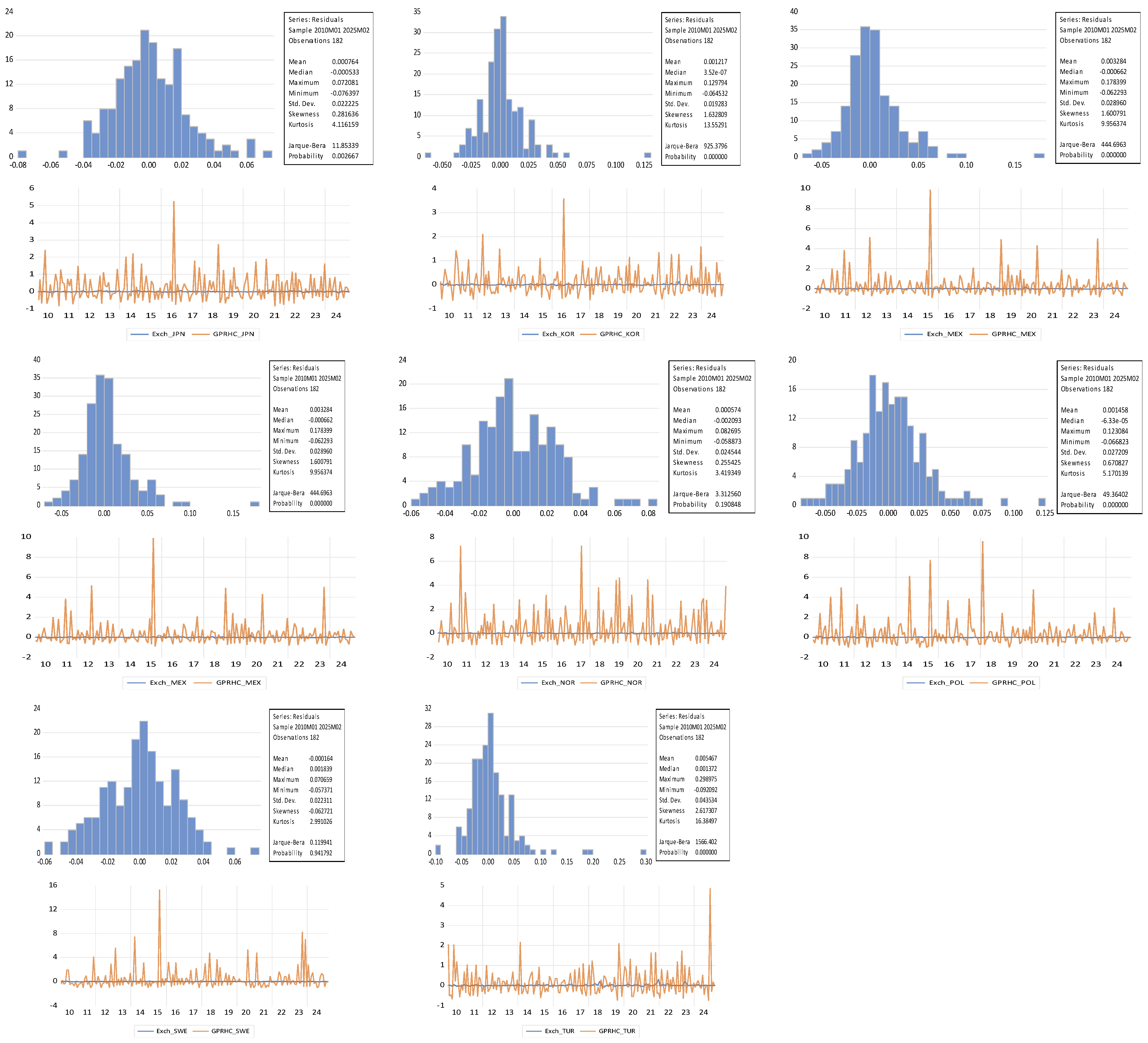

4.2. Normality Test and Distributional Properties of the Residuals (Figure 2)

To examine the statistical behavior of the model innovations, we perform an extensive normality assessment combining the Jarque–Bera test with a visual inspection of the empirical distribution of residuals across all countries. The histograms systematically show clear departures from the Gaussian benchmark: the distributions exhibit marked asymmetry and pronounced fat tails, features typically associated with financial time series subjected to periods of geopolitical stress. Skewness values deviate notably from zero, while kurtosis is exceptionally high for several countries particularly Korea, Mexico, Turkey, and Switzerland reflecting strong leptokurtic patterns.

The Jarque–Bera statistics corroborate this evidence by rejecting the null hypothesis of normality for the vast majority of exchange-rate innovations, with p-values equal to 0.0000 for Switzerland, Korea, Mexico, Poland, Colombia, Turkey, France, Denmark, the United Kingdom, Japan, and Hungary. A few exceptions (such as Canada, Norway, Sweden, and Australia) display borderline acceptance of normality, although their residual distributions still reveal visible tail fattening and asymmetric shapes that remain inconsistent with Gaussian behavior.

Overall, the persistence of heavy tails and asymmetric innovations indicates that the standard normality assumption underlying classical VAR and conventional TVP-VAR models is not appropriate for our dataset. These findings provide strong justification for adopting a heavy-tailed specification such as using a multivariate Student-t distribution for the stochastic-volatility innovations to obtain more reliable posterior estimates and to adequately capture the influence of extreme geopolitical episodes on exchange-rate dynamics.

Figure 2.

Histogram-Based Assessment of Residual Normality and Time-Series Patterns of Innovations.

Figure 2.

Histogram-Based Assessment of Residual Normality and Time-Series Patterns of Innovations.

4.3. Transition to the Bayesian Time-Varying Parameter VAR Framework

The evidence from the normality tests highlights the structural limitations of the classical VAR and other linear models with constant coefficients. The presence of heavy tails, pronounced asymmetry, and strong time-varying volatility suggests that the relationship between geopolitical risk and exchange-rate movements cannot be reliably captured by a framework based on fixed, Gaussian innovations. Such instability—combined with the occurrence of large and infrequent geopolitical shocks—calls for a more flexible model capable of allowing parameters, shock transmission, and volatility to evolve over time.

In light of these considerations, we move from the benchmark VAR specification to a Bayesian Time-Varying Parameter VAR with Stochastic Volatility (TVP-VAR-SV). This framework is particularly well suited to modeling the dynamic, nonlinear, and regime-dependent interactions between exchange rates and geopolitical uncertainty. It accommodates gradual structural shifts as well as abrupt changes associated with major geopolitical episodes. Moreover, given the strong rejection of normality in the residuals, the innovation process is modeled using a multivariate Student-t distribution rather than a Gaussian one. This heavy-tailed specification leads to more robust posterior inference and provides a more realistic representation of extreme geopolitical shocks.

4.4. Out-of-Sample Forecast Validation

To assess the predictive reliability of the Bayesian TVP-VAR with Stochastic Volatility model, we implement an out-of-sample forecast evaluation. This procedure allows us to examine whether the model is capable of generating accurate forecasts beyond the estimation sample and whether its additional flexibility offers meaningful improvements relative to more traditional approaches. We adopt a rolling-window scheme, in which the model is first estimated over an initial subsample and subsequently re-estimated as the window expands. This generates a sequence of real-time forecasts that reflect the model’s adaptive response to new information.

The predictive performance of the TVP-VAR-SV model is benchmarked against two standard alternatives frequently used in the exchange-rate and uncertainty literature: a constant-parameter VAR model, and a conventional TVP-VAR specification without stochastic volatility. These comparisons are essential to determine whether the inclusion of time-varying coefficients, stochastic volatility, and heavy-tailed innovations provides a tangible improvement in forecasting ability.

Forecast accuracy is evaluated using two widely used loss functions the Mean Squared Error (MSE) and the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) computed over the out-of-sample horizon. To formally assess whether differences in predictive performance are statistically significant, we employ the Diebold-Mariano test, which evaluates whether the forecast errors of the TVP-VAR-SV model outperform those of the benchmark models.

Across the majority of countries, the Bayesian TVP-VAR-SV model yields lower forecast errors and demonstrates statistically superior predictive performance. These gains are particularly evident during episodes of heightened geopolitical tensions, when exchange-rate volatility becomes more pronounced and the limitations of fixed-parameter models are most apparent. The results confirm that allowing coefficients and volatility to vary over time and modeling innovations using a heavy-tailed distribution substantially enhances the model’s ability to capture abrupt and extreme movements in exchange rates driven by geopolitical shocks.

4.5. Bayesian TVP-VAR Model and Identification of Geopolitical Risk Shocks

To quantify the impact of geopolitical risk on bilateral exchange rates against the U.S. dollar, we estimate, for each country i and each month t, a Bayesian Time-Varying Parameter Vector Autoregressive model with stochastic volatility (TVP-VAR-SV). This framework allows the sensitivities of the variables to evolve endogenously over time, captures gradual regime shifts without imposing exogenous break dates, and explicitly accounts for time-varying shock volatility. Such flexibility is essential in an environment characterized by recurrent geopolitical disturbances and pronounced financial instability.

For each country

i at time

t, the vector of endogenous variables is defined as:

where

denotes the logarithm of the bilateral exchange rate against the U.S. dollar, and

represents the country-specific geopolitical risk index.

The model is expressed as follows:

where

is a vector of time-varying intercepts,

are time-varying autoregressive coefficient matrices, and

denotes the vector of reduced-form innovations. In line with the distributional evidence reported in

Section 4.2, the innovations are assumed to follow a multivariate Student-t distribution with

degrees of freedom, allowing for excess kurtosis and extreme geopolitical shocks.

The evolution of the time-varying coefficients follows a random-walk state equation:

Stochastic volatility is introduced through the time-varying covariance matrix of the innovations:

where each log-volatility component evolves as:

To identify structural geopolitical risk shocks, the reduced-form model is transformed into its structural representation:

The

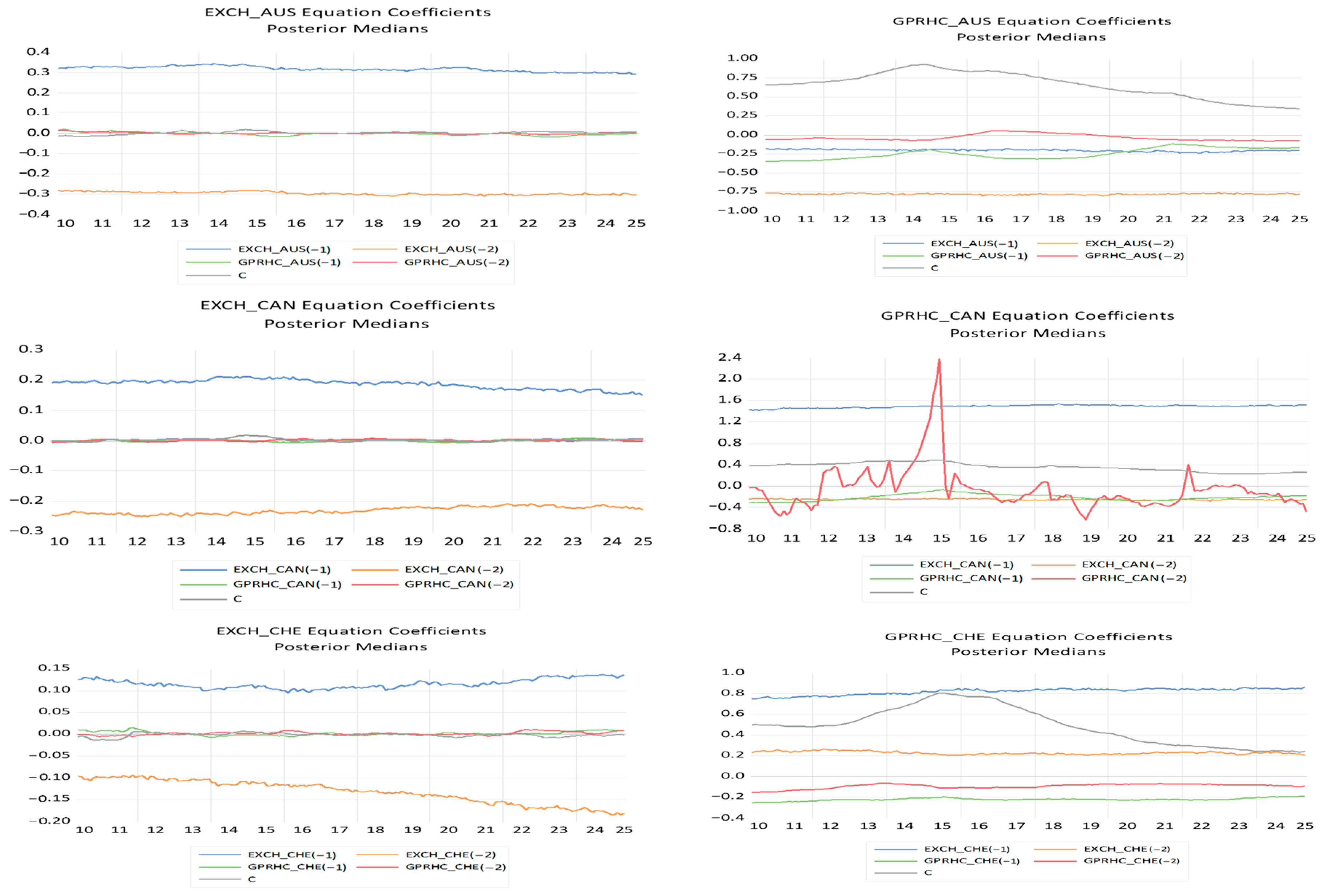

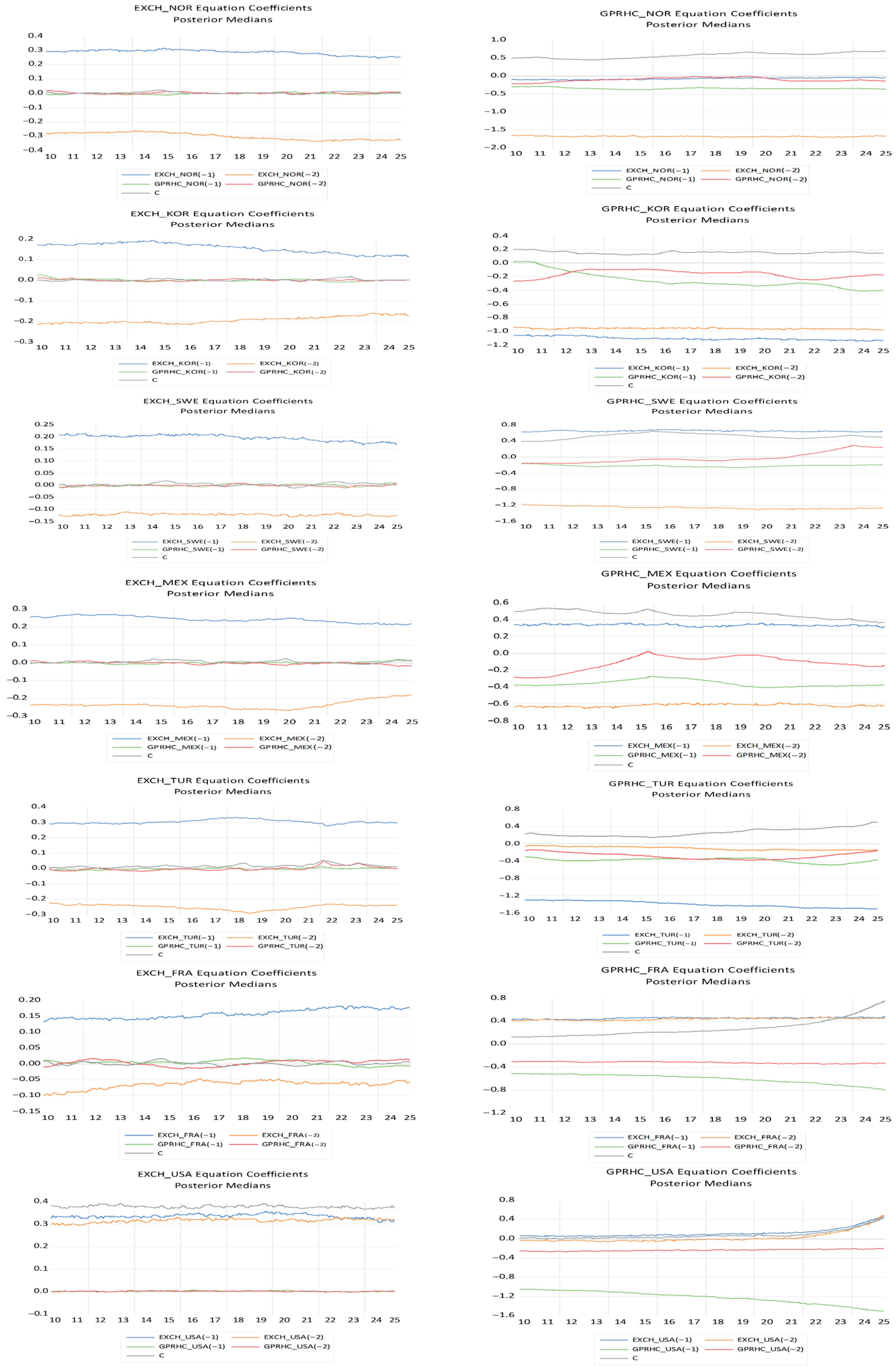

Figure 3 reports that Bayesian TVP-VAR Estimation.

The time-varying coefficients estimated from the Bayesian TVP-VAR with stochastic volatility reveal pronounced heterogeneity in exchange-rate responses to geopolitical risk across OECD economies. Unlike static models that impose constant sensitivities, the TVP-VAR framework captures the evolving and nonlinear nature of the exchange-rate–geopolitical-risk relationship over a period characterized by successive global shocks, including the European sovereign debt crisis (2010–2012), the escalation of Russia–Ukraine tensions (2014) and the full-scale invasion (2022), the COVID-19 pandemic (2020), and recurrent episodes of heightened global uncertainty. The evolution of the coefficients exhibits clear shifts around these events, highlighting the state-dependent nature of currency reactions to geopolitical stress.

In energy-exporting economies such as Australia and Canada, the estimated coefficients fluctuate in close connection with global risk sentiment and commodity-price cycles. In Australia, the sensitivity of the exchange rate to geopolitical risk intensifies during the European debt crisis and again around the COVID-19 period, reflecting exposure to disruptions in global trade and Asian supply chains. These effects subsequently weaken, indicating the capacity of a flexible exchange-rate regime and credible monetary institutions to absorb external shocks. Canada displays a similar pattern, albeit with sharper swings during 2014–2015 and 2022, when geopolitical tensions coincided with volatility in global oil markets. The relatively rapid normalization of the coefficients points to effective shock-absorption mechanisms.

Safe-haven economies, represented by Switzerland and Japan, exhibit a markedly different profile. In both cases, the time-varying coefficients become persistently negative during major uncertainty episodes, indicating systematic currency appreciation in response to geopolitical shocks. The smooth and sustained evolution of these coefficients reflects strong investor confidence and a recurrent flight-to-quality mechanism, particularly evident during the COVID-19 crisis and the 2022 geopolitical escalation.

In contrast, emerging and externally vulnerable economies display heightened and more persistent sensitivity to geopolitical risk. In Chile, Colombia, and Mexico, the coefficients increase sharply during periods of global stress, especially after 2019 and during the 2020 commodity-price collapse. These dynamics are consistent with rising risk premia, capital outflows, and increased exposure to global financial conditions. Although the coefficients eventually decline, their slow adjustment highlights limited shock-absorption capacity in economies with strong external dependence.

European economies present a more nuanced picture reflecting differences in monetary frameworks and geopolitical exposure. In the United Kingdom, coefficient estimates rise notably during Brexit-related uncertainty, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the 2022 conflict, underscoring heightened sensitivity in a post-Brexit environment. France, Denmark, and Sweden exhibit more moderate and shorter-lived increases in sensitivity, consistent with strong institutional frameworks and deeper financial markets. Sweden, in particular, shows rapid convergence following uncertainty episodes, reflecting high policy credibility and monetary flexibility.

Central and Eastern European economies such as Poland and Hungary experience some of the strongest regime shifts. Their coefficients rise substantially during the 2014 Crimea crisis and again after the 2022 invasion, reflecting geographical proximity to the conflict, energy-security concerns, and non-euro exchange-rate regimes. The persistence of elevated coefficients suggests prolonged vulnerability to geopolitical instability and investor risk reassessment.

Finally, other advanced economies display mixed but interpretable dynamics. In Norway, coefficient increases during 2014 and 2022 reflect the interaction between geopolitical risk and energy-export expectations. South Korea shows temporary increases in sensitivity during regional security tensions and global uncertainty peaks, followed by relatively rapid normalization supported by a diversified industrial base. The United States stands apart, with limited variation in coefficient estimates, reaffirming the dominant role of the U.S. dollar as a global safe-haven currency.

Overall, the time-varying estimates confirm that the sign, magnitude, and persistence of exchange-rate reactions to geopolitical shocks depend critically on economic structure, external exposure, and monetary credibility. Safe-haven currencies (USD, CHF, JPY) consistently appreciate in response to geopolitical risk, while emerging-market currencies (TRY, CLP, COP, MXN) tend to depreciate more strongly and persistently. Intermediate economies (AUD, CAD, NOK, SEK) exhibit temporary but responsive adjustments. These results underscore that the exchange-rate–geopolitical-risk nexus is neither stable nor linear, thereby justifying the use of a time-varying framework.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This study provides robust evidence that geopolitical risk has become a central driver of exchange-rate dynamics across OECD economies. By employing a Bayesian TVP-VAR framework with stochastic volatility and heavy-tailed innovations, the analysis uncovers substantial heterogeneity in currency responses that would remain hidden under constant-parameter specifications.

The results confirm that geopolitical risk operates as a global uncertainty channel, influencing exchange rates primarily through shifts in investor sentiment, capital-flow reallocations, and changes in risk premia. These effects intensify during major global disruptions—such as the European sovereign debt crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the Russia–Ukraine conflict—periods during which pronounced regime shifts in exchange-rate sensitivities are observed. This validates the relevance of a dynamic modeling approach capable of capturing evolving and regime-dependent transmission mechanisms.

Three broad patterns emerge: First, safe-haven currencies, including the U.S. dollar, the Swiss franc, and the Japanese yen, systematically appreciate during episodes of heightened geopolitical uncertainty, reinforcing their stabilizing role in international financial markets. Second, energy-exporting economies such as Norway and Canada benefit from mitigating effects linked to commodity price dynamics, which help cushion exchange-rate pressures despite global turbulence. Third, emerging and externally vulnerable economies, notably Turkey, Mexico, Chile, and Colombia, experience more pronounced and persistent depreciations, driven by capital outflows, weaker institutional credibility, and heightened exposure to global risk aversion.

From a methodological standpoint, the findings highlight the added value of incorporating time-varying parameters, stochastic volatility, and heavy-tailed innovations. The Bayesian TVP-VAR-SV model delivers superior predictive performance relative to traditional VAR frameworks, particularly during periods of elevated volatility, confirming its suitability for analyzing uncertainty-driven shocks.

The policy implications are significant. For advanced economies, maintaining credible monetary frameworks and clear communication strategies is essential to mitigate speculative pressures during crises. For emerging markets, strengthening macroeconomic fundamentals, diversifying external financing sources, and building adequate external buffers are key to reducing vulnerability to geopolitical shocks. More broadly, the growing frequency and intensity of geopolitical tensions underscore the importance of integrating geopolitical-risk indicators into macroeconomic surveillance and monetary-policy decision-making.

In conclusion, geopolitical risk should be viewed as a persistent and structural factor shaping modern exchange-rate dynamics. By capturing the evolving, asymmetric, and regime-dependent nature of these effects, the Bayesian TVP-VAR framework provides valuable insights for both researchers and policymakers seeking to understand and manage currency behavior in an increasingly uncertain global environment.