1. Introduction

Food inflation represents a real challenge for developing economies, particularly in a context marked by climate instability and high exposure to global market fluctuations. In Morocco, the dependence on cereal imports, combined with climatic variations, has negatively impacted the food system. Food self-sufficiency has been a strategic national priority since independence and continues to be a central objective of the country’s development policy (

Michael, 2021). According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (

FAO, 2023b), global food prices have begun to decline gradually since the peak of 21% recorded in 2023, highlighting the importance of analyzing the factors behind this volatility.

In this context, the exchange rate plays a central role in food price setting, particularly through the Exchange Rate Pass-Through (ERPT) mechanism. Morocco, as a country that is highly integrated into the global economy, has adopted a fixed exchange rate regime since the 1970s, pegging the dirham to a basket of currencies that reflect the country’s openness to trade (

Erraitab et al., 2024). This regime aimed to ensure the stability of the national currency in terms of the nominal effective exchange rate, while reducing fluctuations in the currencies comprising the basket (

Bank Al-Maghrib, 2025). However, this system allowed operators to satisfy their foreign currency needs without limit, thus exerting significant pressure on exchange reserves and potentially compromising the Central Bank’s (

Bank Al-Maghrib, 2025) ability to honor its external commitments. For this reason, on 15 January 2018, Morocco began a gradual transition to a flexible exchange rate regime, widening the dirham’s fluctuation band to a central rate based on a basket composed of 60% euro and 40% U.S. dollar (

Bank Al-Maghrib, 2025). This reform aims to strengthen the competitiveness of the Moroccan economy, better absorb external shocks, and support growth.

From this perspective, it is essential to conduct an analysis of the impact of exchange rate fluctuations on cereal and food prices in Morocco, while also taking into account the decisive role of climatic factors. Neoclassical growth theory (

Mankiw et al., 1992) argues that food security depends on the availability of labor, capital, and technology factors, all of which are vulnerable to climate shocks. In addition, resilience theory (

Levin et al., 1998;

Folke, 2016) highlights the capacity of food systems to absorb and recover from environmental disturbances, particularly through crop diversification, sustainable water management, and soil conservation (

Tinta et al., 2018;

Friel et al., 2020). Given Morocco’s dependency on imported food products, particularly cereals, exchange rate volatility combined with climate risks can have a significant impact on domestic prices and the cost of living.

This study therefore aims to analyze the combined impact of the exchange rate regime and climate variability on food prices and cereal prices in Morocco, using an integrated econometric approach.

Three main research contributions are advanced in this study. First, it adopts a mixed-methods approach combining qualitative and quantitative analyses. Second, it integrates both economic and environmental perspectives to examine food and cereal inflation, including the ERPT concept and climatic variables such as rainfall and temperature. Third, it employs linear and nonlinear ARDL models to capture short- and long-term interactions and to assess both cointegration and asymmetry among the variables.

This study is structured as follows. After the introduction section, the “literature background” section presents an analysis of the international and national literature related to ERPT and climate variability effects on food prices and cereal inflation. The “Contextual background” section analyzes the national evolution of the exchange rate regime, food price stability, and climate change challenges. The “Model construction and variables selection” section presents the empirical approach used in this research and explain the data basis. Before the “Conclusion” section, the “Results and discussion” section presents the empirical findings.

2. Literature Background

The theoretical framework of exchange rate pass-through (ERPT) related to food inflation is rooted in the international transmission mechanism of prices, where exchange rate fluctuations influence domestic inflation through importation. In developing economies, the depreciation of the exchange rate increases the cost of imported primary commodities and capital goods, which in turn raises production costs and domestic prices, as highlighted by

Hyder and Shah (

2004).

Taylor (

2000) adds that in price stability conditions, firms may have reduced pricing power, leading to a lower degree of pass-through. This indicates that the macroeconomic context plays a critical role in determining the factors of ERPT. Moreover,

Sabiston (

2001) describes incomplete pass-through as a situation where domestic prices do not fully respond to exchange rate volatility, often due to nominal rigidities, pricing-to-market strategies, or policy buffers.

From a more applied perspective, (

McCarthy, 2007;

Soto & Selaive, 2003;

Nasir et al., 2020) have highlighted the structural role of trade liberalization in the degree of exchange rate transmission. Greater openness to international trade tends to increase the sensitivity of domestic prices to currency fluctuations.

Various studies, in the international framework, analyze the causality between the exchange rate and food inflation using econometric models.

Ozdogan (

2022), presents an empirical analysis related to the partiality and the structure of ERPT on the consumer price index (CPI) inflation based on the VAR Model in Turkey. The findings demonstrate that ERPT is partially incomplete but also has a different structure during the floating exchange rate period. Related to the same country,

Çam (

2024) examines the pass-through effect of the USD/TRY exchange rate on domestic food prices in Türkiye during the period 2003–2023 using a VAR method and finds a 27% total pass-through effect, with 12% attributed to food trade and 90% to domestic dynamics.

However,

Zamanzadeh’s (

2024) findings, obtained from a VECM model applied to Iran, indicate that setting preferential exchange rates leads to a decrease in the degree of exchange rate pass-through (ERPT) during the stabilization period.

Similarly,

Vo and Vu (

2024) analyze the pass-through mechanism in several European countries using an ARDL model covering the period from 2006M1 to 2022M12. The study reveals that, in contexts marked by high uncertainty, policymakers assess the compromise between exchange rate risks and macroeconomic stability.

In the Moroccan context, the analysis of the ERPT on the consumer price index (CPI) was initiated by

Rachidi and Assandadi (

2016), who examined the period 2000–2014 using the VAR model. Their results show that exchange rate fluctuations have a significant impact on inflation, although the degree of pass-through observed remains relatively moderate.

The study of

Chatri et al. (

2016), based on a VAR model applied to the period 1990–2015, highlights a low reactivity of the ERPT in Morocco, which tends to decrease in the long run with an impact that is more pronounced for tradable goods than non-tradable goods.

After 2018, the year that marked Morocco’s transition to a more flexible exchange rate regime,

Baya et al. (

2024), covering the period 2000–2021 with a Structural VAR model, concluded that a shock to the exchange rate has a significant impact on inflation, although the pass-through mechanism remains incomplete (pass-through < 1). The results also reveal a notable decline in the degree of pass-through over time, attributed to various structural factors. This dynamic suggests that the observed level of transmission is not high enough to compromise the implementation of inflation-targeting, in parallel with the transition to a more flexible exchange rate regime.

On the other hand, the national research that explores the ERPT on food prices was analyzed by

Mansouri et al. (

2024), who adopted a quantile regression applied to quarterly data covering the period 2008–2022. The findings show that exchange rate transmission has a positive and significant effect on food inflation. Conversely, oil prices appear to have a negative impact on food prices.

Furthermore,

El-Karimi and El-Ghini (

2020) extend the research on this scope by analyzing the effect of ERPT on global food commodity prices using the SVAR model during the period 2004–2018. This study reveals that external positive shocks generate a stronger local food price response than negative ones.

While studies on the ERPT in food and cereal price inflation have provided a better understanding of the monetary and trade effects on inflationary dynamics, they remain insufficient to fully grasp the structural causes of this inflation. Indeed, climate change is a determining factor that is often studied in conventional economic analyses. The Neoclassical growth theory of

Mankiw et al. (

1992) emphasizes that food security depends on the availability of capital, labor, and technology, but these factors are themselves vulnerable to climate shocks.

Moreover, the theory of resilience (

Levin et al., 1998;

Folke, 2016) argues that the ability of food systems to absorb and recover from climate challenges is essential. Practices such as crop diversification, sustainable water management, and soil conservation (

Tinta et al., 2018;

Friel et al., 2020) are therefore essential for mitigating the effects of climate variability on food security. Integrating this environmental dimension into ERPT analysis thus provides a better understanding of the mechanisms of food inflation, particularly in contexts marked by climate constraints.

From a quantitative approach,

Ichoku et al. (

2023) analyze the relationships between climate change, insecurity, and food price inflation in Nigeria using an NARDL model. They found that insecurity and climate change shocks are significant determinants of food inflation in Nigeria.

Furthermore,

Odongo et al. (

2022) use a descriptive analysis covering ten Eastern and Southern African countries to demonstrate the impact of climate change on food inflation. The study argues that rainfall and imported food prices are the main determinants of food inflation.

However, nationally,

Soumbara and El Ghini (

2024) use a nonlinear ARDL model to analyze the effects of climate change constraints on food price stability in Morocco, covering the period 1961–2020. The study found a long-term asymmetric relationship between rainfall and the food price index, whereby positive rainfall shocks have a stronger effect than negative shocks, exerting a long run impact on food production. The present study does not take into consideration the exchange rate effect.

Despite previous studies related to ERPT on food inflation and cereal prices, the existing literature remains limited in the Moroccan context. It neglects the impact of climate variability on cereal price stability and does not incorporate a mixed methodological approach that would allow for a qualitative and quantitative analysis of the economic and environmental dimensions.

This gap prevents a comprehensive understanding of the interactions between economic policies, the Moroccan environmental context, and their joint effects on the food price index and cereal prices.

Furthermore, this research fills a gap in the literature by offering an updated long-term analysis using the ARDL model and the NARDL bound test to check the asymmetry and cointegration between variables. This contribution thus provides a relevant analytical framework for economic policy decisions in the context of the transition to a more flexible exchange rate regime and environmental challenges that could impact food and cereal price stability.

3. Contextual Background: Economic, Monetary and Environmental Trends in Morocco

The past twenty years have been marked by significant economic, monetary, and environmental changes in Morocco. The country began a gradual transition from a fixed to a flexible exchange rate regime. Launched in 2018, this reform aimed to enhance economic resilience to external shocks and improve competitiveness.

During this same period, inflation remained relatively stable, while the peak was observed notably in 2022 when it reached 6.2% (

World Bank, 2024). At the same time, cereal prices increased significantly, mainly due to recurring droughts and an increase in cereal importation (

El Ansari et al., 2023).

3.1. Macroeconomic and Monetary Dynamics in Morocco

Morocco, as a developing country, has prioritized trade liberalization and foreign direct investment (FDI) promotion, both of which have contributed significantly to sustained economic growth and macroeconomic stability (

Bank Al-Maghrib, 2025).

From a monetary perspective, Morocco’s exchange rate regime has undergone important transformations. Between 1960 and 1970, the exchange rate was fixed at 5 MAD per USD, following the adoption of the Moroccan Dirham. After 1970, the exchange rate began to fluctuate, with a notable 37% depreciation in 1981 during the Structural Adjustment Program (

Bank Al-Maghrib, 2025). In 1999, Morocco adopted a currency basket system, replacing European currencies with the Euro, and maintained a relatively stable rate around 9 MAD per USD. Recently, the Central Bank widened the fluctuation band of the Dirham to ±2.5% in 2018 and to ±5% in 2020, while keeping the basket value unchanged. Since then, the exchange rate has fluctuated between 9.49 and 19.13 MAD per USD (

Bank Al-Maghrib, 2025).

These macroeconomic strategies have not only influenced Morocco’s growth trajectory but have also had a direct impact on price stability. In particular, the interaction between exchange rate adjustments, the vulnerability of the agricultural sector, and external shocks has contributed to the volatility of food inflation.

3.2. Climate Vulnerabilities and the Agricultural Sector

In an international context marked by intensifying environmental challenges, Morocco is a country that exemplifies the challenges related to water scarcity in semi-arid to arid climates (

World Bank, 2020). Since 1980, rainfall has decreased by approximately 25%, while temperatures have risen continually, thereby increasing the probability of droughts occurring (

Balaghi et al., 2024).

According to the World Resources Institute (WRI) ranking of the year 2023, Morocco ranks 27th among the countries most exposed to the risk of water scarcity (

World Resources Institute, 2023). Annual freshwater availability per capita has fallen significantly from over 2000 cubic meters in 1960 to less than 600 cubic meters today, well below the water stress threshold defined by the World Bank.

This vulnerability is intensified by Morocco’s heavy dependence on irrigated agriculture, which accounts for nearly 87% of national freshwater withdrawals (

UNESCO, 2020). Intensive irrigation, overexploitation of groundwater, and low irrigation system efficiency contribute to increasing pressure on water resources and accelerating the degradation of aquatic ecosystems (

Gu et al., 2017). These facts underscore the urgent need to rethink integrated water management strategies in the context of climate change and food security.

The agricultural sector’s contribution to GDP in Morocco has declined significantly since the mid-1970s, stabilizing at around 12% over the past twenty years (

El Haddadi et al., 2025). This reflects a broader structural transformation of the economy, with increasing emphasis on industry and services, while agriculture remains vital for employment and food security.

In this context, the effects on agricultural productivity, especially cereals, are particularly pronounced. The production of barley, maize, and wheat is characterized by permanent fluctuations depending on climatic conditions (

Belmahi et al., 2023). Furthermore, a significant decrease in cereal production was recorded during the years 2020 and 2022, with total volumes of 33.255 thousand quintals and 35.097 thousand quintals, respectively, compared to 2018 and 2021, which were marked by peaks in cereal production (with volumes of 103.897 thousand quintals and 104.521 thousand quintals, respectively) (

World Bank, 2024).

These marked fluctuations in cereal production, largely driven by climate change, have direct repercussions on market dynamics.

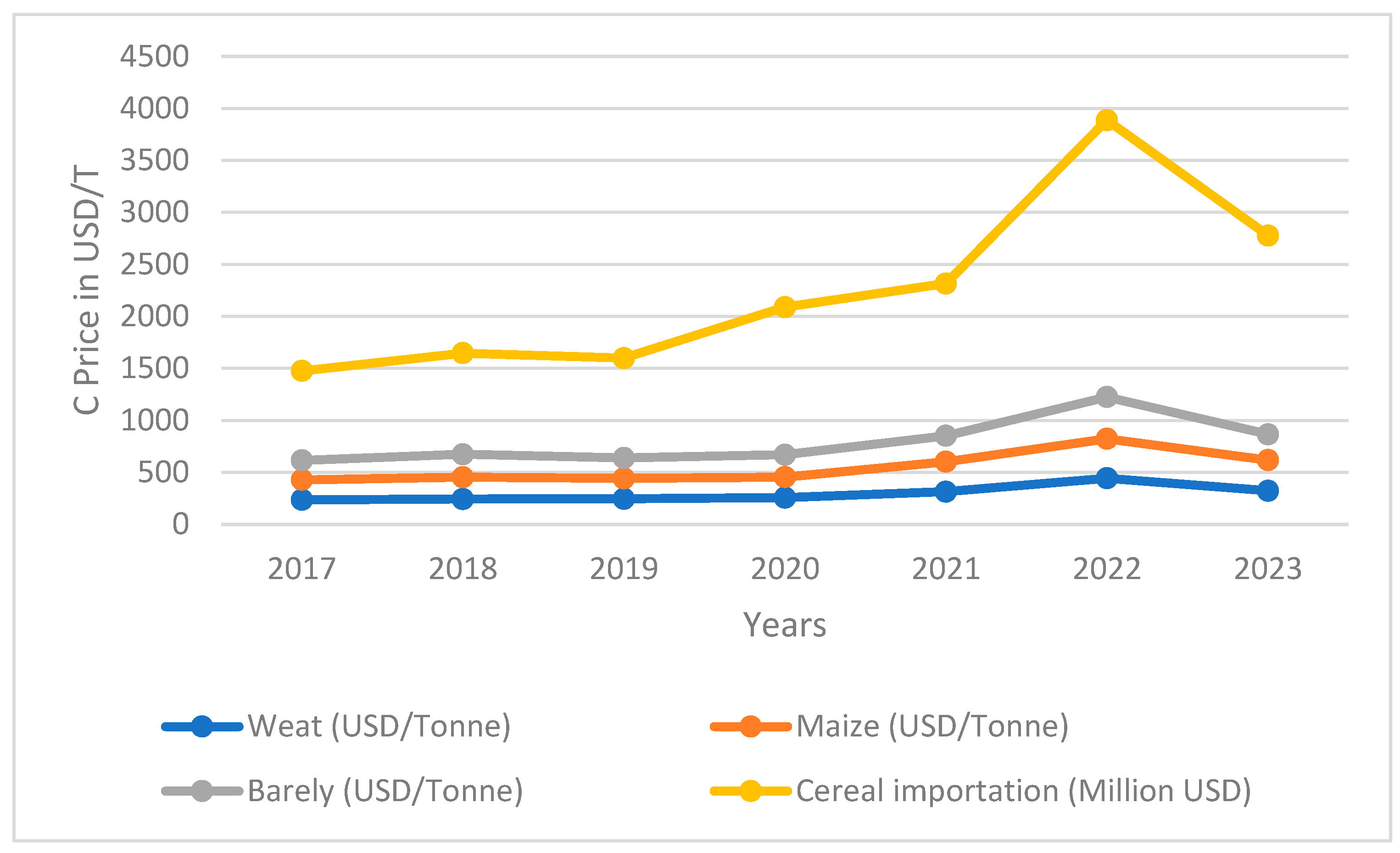

Figure 1 below shows the evolution of the Moroccan import volume of the three types of cereals and the evolution of cereal prices during the period 2017–2023.

The data indicate a general upward trend in the prices of wheat, maize, and barley from 2017 to 2023, with a notable peak in 2022 for the three main cereals. This trend is potentially correlated with the cereal import costs, which also peaked in 2022. The decrease in 2023 suggests potential stabilization or correction in the market.

4. Data and Methods

The choice of variables in this study is grounded in both theoretical and empirical literature on exchange rate pass-through and food price dynamics in emerging economies. The food consumer price index (IPCF) serves as the dependent variable, representing domestic food inflation, which is a critical component of overall consumer prices in Morocco (

Bank Al-Maghrib, 2024). The nominal effective exchange rate (NEER) is included to capture the external price transmission mechanism, reflecting how currency fluctuations affect import prices and, consequently, domestic food costs. Numerous studies have shown that exchange rate depreciation tends to increase domestic prices, particularly in small open economies (

Choudhri & Hakura, 2015;

El-Karimi & El-Ghini, 2020).

The inclusion of international oil prices (OIL) acknowledges the indirect cost channel, as higher energy prices raise transportation, irrigation, and fertilizer costs in agriculture, ultimately pushing up retail food prices. This channel has been highlighted in studies by

Kilian and Zhou (

2022) and by

El-Karimi and El-Ghini (

2020) for the Moroccan case. The world cereal price index (CER) proxies global food price shocks, which are transmitted through import and expectation channels (

Tadesse et al., 2016). In developing and import-dependent economies, world food price volatility exerts a significant influence on local inflation dynamics (

Abbott et al., 2011).

The volume of food imports (IMP) is introduced to account for the degree of exposure of domestic prices to international markets. The higher the reliance on imported food commodities, the stronger the pass-through effect from external shocks (

Bayoumi & Eichengreen, 1995;

El-Karimi & El-Ghini, 2020). Finally, precipitation (PR) represents a key climatic factor in Morocco’s food inflation dynamics. The country’s agricultural output is heavily dependent on rainfall due to limited irrigation capacity (

FAO, 2022), making climate shocks a significant determinant of food supply and price volatility (

Moessner & de Haan, 2022). Recent empirical evidence confirms that weather anomalies and droughts exert nonlinear effects on inflation, amplifying volatility in food prices (

Moessner & de Haan, 2022).

Overall, the inclusion of these variables allows the model to capture both external transmission mechanisms (exchange rate, oil and commodity prices, imports) and domestic supply-side shocks (rainfall variability), consistent with previous empirical frameworks applied to Morocco and other developing economies (

El-Karimi & El-Ghini, 2020;

Moessner & de Haan, 2022).

4.1. Data Specification

The empirical analysis relies on monthly time-series data for Morocco, covering the period from October 2009 to May 2025, resulting in a total of 185 observations after seasonal adjustment. The starting point is determined by the availability of consistent data on food prices and the nominal effective exchange rate following the gradual liberalization of Morocco’s exchange rate regime in 2009 (

Bank Al-Maghrib, 2024). This period also captures key external shocks—including the 2018 exchange-rate band widening, the 2020 COVID-19 disruption, and the 2022 commodity and climatic shocks—making it particularly relevant for studying exchange rate pass-through (ERPT) and food inflation dynamics.

All variables in

Table 1 except temperature (TP) are expressed in natural logarithmic form, allowing the estimated coefficients to be interpreted as elasticities. Log-transformation also stabilizes variance and mitigates potential heteroskedasticity in the series (

Gujarati & Porter, 2020). The temperature variable (TP) is maintained in its level form since it is measured in degrees Celsius and does not meaningfully support a logarithmic transformation.

4.2. Descriptive Statistics

The descriptive statistics in

Table 2 indicate moderate variation across most variables, suggesting stable dynamics suitable for time-series modeling. The food price index (L_IPCF) and exchange rate (L_NEER) show limited dispersion, consistent with Morocco’s managed exchange-rate regime (

Bank Al-Maghrib, 2024). In contrast, oil (L_OIL) and cereal prices (L_CER) exhibit higher volatility, reflecting exposure to global commodity shocks (

El-Karimi & El-Ghini, 2020). The import variable (L_IMP) displays wider fluctuations, mirroring Morocco’s dependence on external food supply. Regarding climate variables, temperature (TP) and rainfall (L_PR) vary substantially, highlighting climatic seasonality. The Jarque–Bera results confirm mild deviations from normality, which are typical in monthly macroeconomic data (

Brooks, 2019;

Wooldridge, 2020). Overall, data distribution supports the application of an ARDL/NARDL framework to capture both short- and long-run effects.

4.3. ARDL Model Specification

This study employs the Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) and Nonlinear ARDL (NARDL) frameworks to analyze both the symmetric and asymmetric effects of exchange rate movements, global commodity prices, and climatic variables on food price inflation in Morocco. The ARDL model, developed by

Pesaran et al. (

2001), is particularly suitable when the variables are integrated of mixed orders I(0) and I(1), but not I(2). It provides consistent short- and long-run estimates through an error correction representation, even in small samples (

Nkoro & Uko, 2016;

P. K. Narayan, 2005).

The general ARDL (

p,

q1, …,

qk) model can be expressed as follows:

where

Yt the dependent variable (L_IPCF) and

represents the set of explanatory variables, including the nominal effective exchange rate (L_NEER), oil prices (L_OIL), cereal prices (L_CER), food imports (L_IMP), precipitation (L_PR), and temperature (TP). The coefficients of the lagged differenced terms capture short-run dynamics, while those associated with lagged levels reflect long-run relationships.

To examine potential asymmetries in the exchange rate pass-through (ERPT) mechanism, the ARDL model is extended to a Nonlinear ARDL (NARDL) formulation following

Shin et al. (

2014). This approach decomposes the exchange rate variable into its positive and negative partial sums, defined as follows:

This decomposition allows the model to capture whether food prices respond differently to currency depreciations and appreciations. The NARDL specification is written as follows:

The long-run asymmetric coefficients are derived as follows:

while the short-run asymmetries are evaluated through Wald tests on the difference between the cumulative coefficients of the positive and negative changes.

To verify the existence of a long-run equilibrium, the bounds testing procedure of

Pesaran et al. (

2001) is applied. The null hypothesis of no cointegration

is tested against the alternative of a long-run relationship. The decision rule is based on comparing the computed F-statistics with the critical values for I(0) and I(1) bounds provided by

P. K. Narayan (

2005) for small-sample corrections.

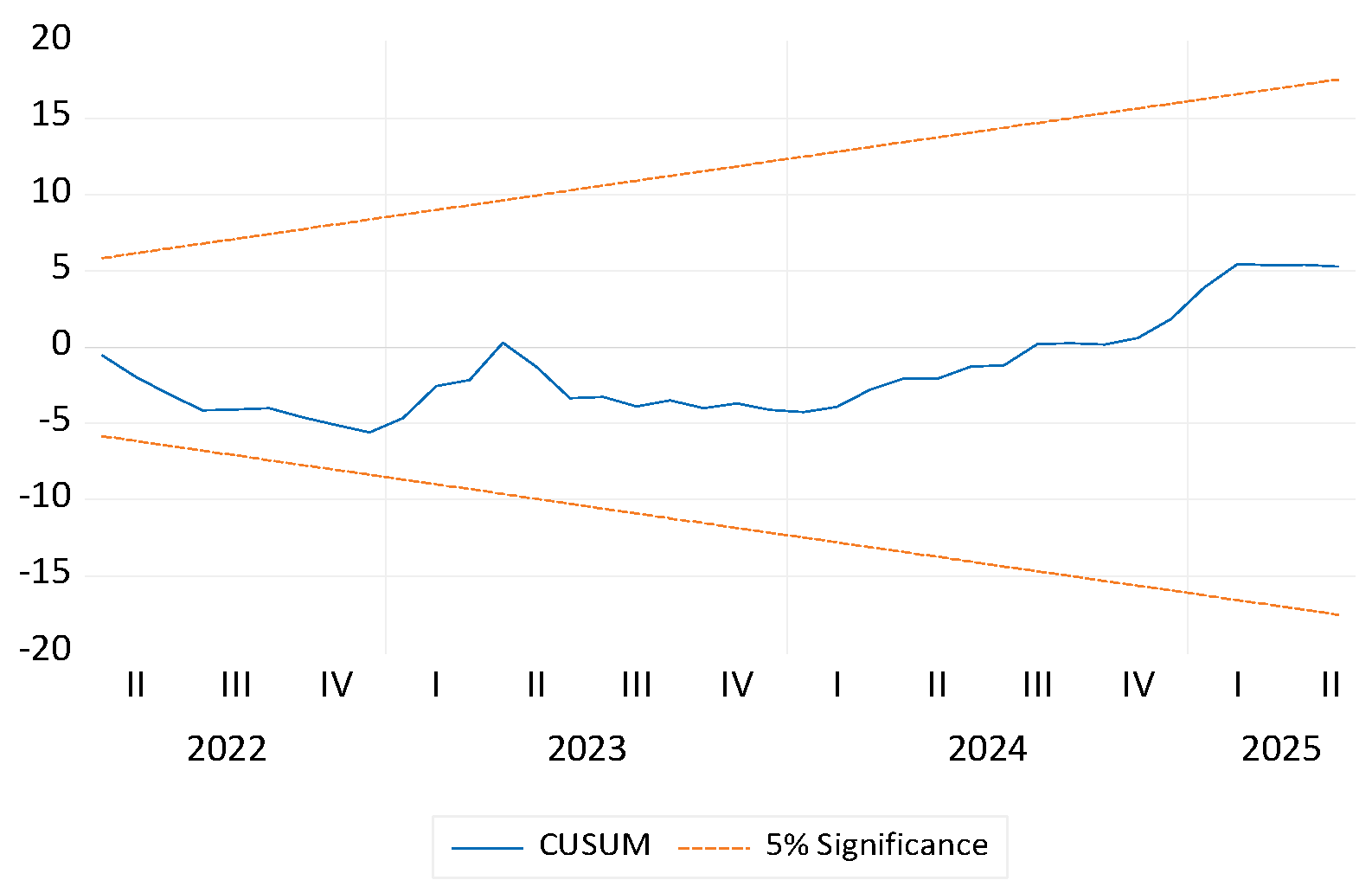

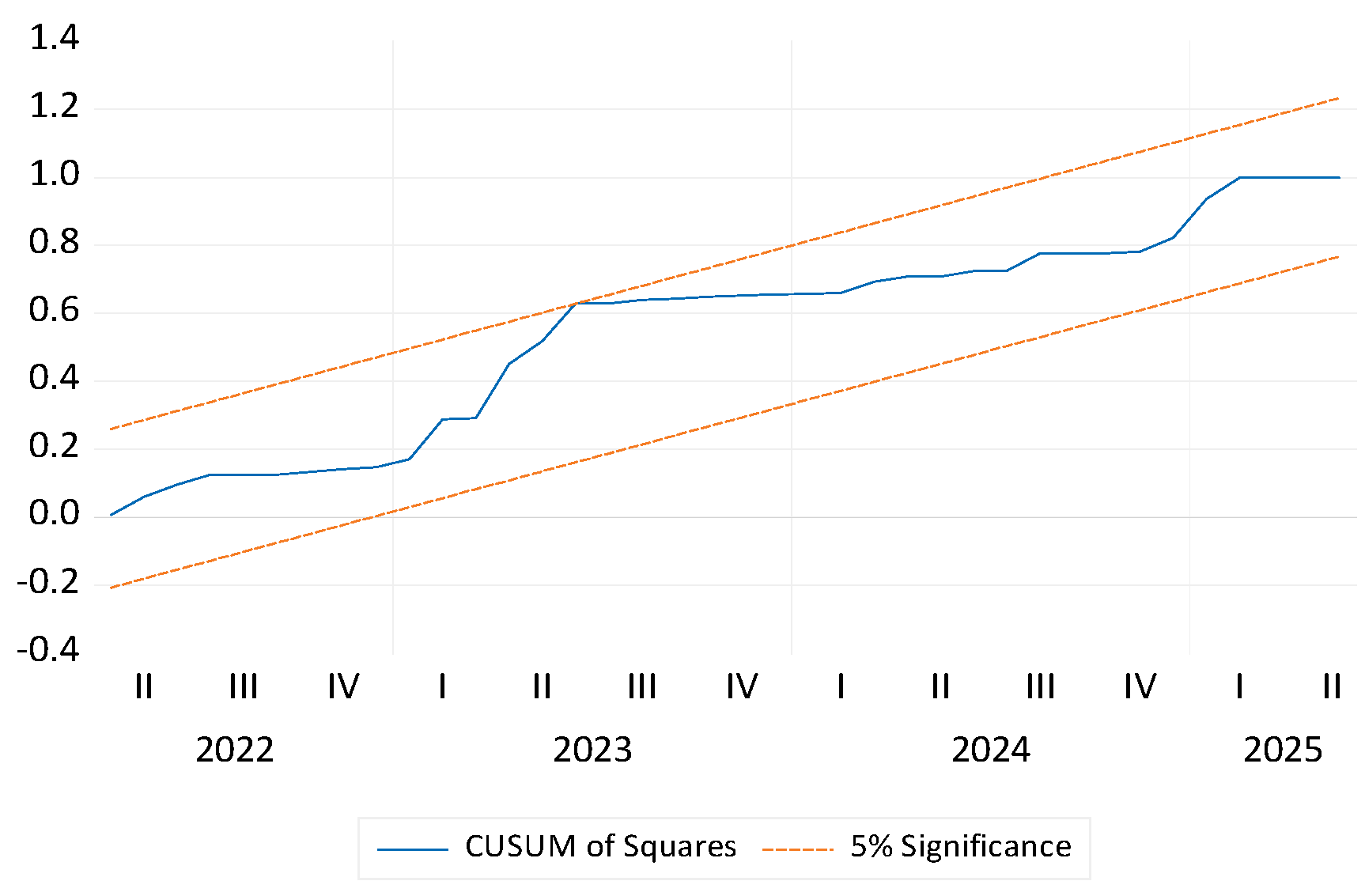

Diagnostic tests are subsequently performed to ensure model adequacy, including serial correlation (Breusch–Godfrey LM), heteroskedasticity (Breusch–Pagan–Godfrey), and functional form misspecification (Ramsey RESET). Structural stability is examined using the CUSUM and CUSUMQ tests, following

Brown et al. (

1975). The use of HAC-robust standard errors ensures valid inference under potential heteroskedasticity.

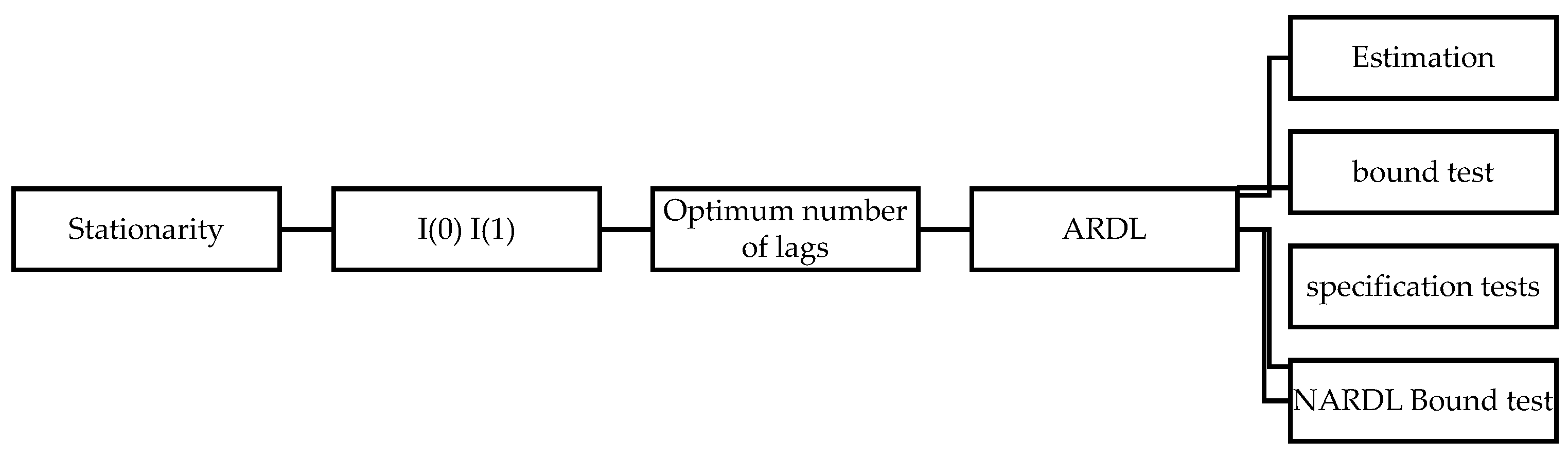

Overall, this methodological framework as summarized in

Figure 2 captures both the short-run adjustment and the long-run asymmetric transmission mechanisms linking global price shocks, exchange rate fluctuations, and climatic variations to Morocco’s food inflation dynamics. The combination of ARDL and NARDL approaches provides flexibility, interpretability, and robustness, making it an appropriate tool for analyzing small-sample, mixed-integration macroeconomic time series (

Shin et al., 2014;

Salisu & Isah, 2018;

Apergis, 2021).

4.4. Stationarity Test

The ADF results in

Table 3 reveal that most variables become stationary after first differencing, implying integration of order one, I(1). Only precipitation (L_PR) is stationary in level, I(0), whereas all other variables—food prices (L_IPCF), nominal effective exchange rate (L_NEER), oil prices (L_OIL), cereal prices (L_CER), imports (L_IMP), and temperature (TP)—exhibit unit roots in levels but achieve stationarity at first difference. This mixture of I(0) and I(1) series confirms the suitability of the ARDL and NARDL modeling frameworks, which are specifically designed to handle regressors integrated of different orders without requiring pre-testing for cointegration (

Pesaran et al., 2001;

Shin et al., 2014).

The absence of any I(2) variable ensures that the estimated long-run coefficients and bound tests are statistically valid within this framework. These findings are consistent with empirical studies applying ARDL models in inflation and exchange-rate analyses for developing economies (

Bahmani-Oskooee & Fariditavana, 2016;

El-Karimi & El-Ghini, 2020).

4.5. Optimum Number of Lags

The determination of the optimal lag structure followed a two-step approach widely adopted in empirical macroeconomic modeling (

Nkoro & Uko, 2016). In the first step, a preliminary VAR lag order selection was performed to establish a reasonable upper bound for lag length. The results of the information criteria in

Table 4 indicated that the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) reached its minimum at lag 6, which was consequently retained as the maximum lag length in the subsequent ARDL estimation. This upper limit is consistent with the monthly frequency of the data, as several studies suggest that six months is a plausible adjustment horizon for macroeconomic and price variables (

Salisu & Isah, 2018;

Lütkepohl, 2006).

In the second step, the automatic lag selection algorithm in EViews 12 was applied within this bound, allowing the program to search across all possible lag combinations and select the specification that minimized the AIC. The resulting ARDL (3,0,0,0,2,0,0) structure offered the best compromise between model flexibility and parsimony, while avoiding over-parameterization. The adoption of the AIC over the Schwarz Bayesian Criterion (SBC) is justified by its superior small-sample efficiency and lower risk of underfitting in dynamic models (

Burnham & Anderson, 2004;

Brooks, 2019).

This approach ensures that the model captures both short-run adjustment mechanisms and the delayed transmission of external shocks, such as exchange rate movements, global oil and cereal price fluctuations, without compromising model stability. Similar lag selection strategies have been successfully employed in recent ARDL applications for inflation and exchange-rate dynamics in emerging economies (

Bahmani-Oskooee & Gelan, 2018;

El-Karimi & El-Ghini, 2020;

Salisu & Isah, 2018).

4.6. Estimation Procedure

The model was estimated using HAC (Newey–West) robust standard errors to correct for potential heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation (

Newey & West, 1987). Three structural dummy variables (

Table 5) were included—S2018 (exchange rate band widening), S2020 (COVID-19), and S2022 (global commodity shock)—to capture key regime shifts influencing inflation dynamics (

IMF, 2019;

World Bank, 2023). Diagnostic tests (LM, BPG, RESET, CUSUM, and CUSUMQ) confirmed the model’s validity and stability (

Brown et al., 1975).

6. Discussion and Policy Implications

The empirical findings provide meaningful insights into the dynamics of food price inflation in Morocco and the transmission of exchange rate shocks to domestic prices. The results from the ARDL and NARDL estimations reveal that while the nominal effective exchange rate (NEER) affects food prices, the pass-through effect remains modest and symmetric, with no statistically significant difference between appreciations and depreciations. This outcome is consistent with earlier evidence for small open economies with managed exchange rate regimes, such as Tunisia (

Ben Cheikh, 2016) and Egypt (

H. Aly & El-Shamy, 2018), where monetary authorities intervene to stabilize imported price shocks.

The error correction term (−0.099) indicates a relatively slow speed of adjustment—about 10 percent of disequilibrium corrected per month—highlighting persistence in Morocco’s food inflation. This inertia can be attributed to price rigidities in agricultural markets, lagged adjustments in import contracts, and the partial insulation effect of subsidies under the Compensation Fund (

Bank Al-Maghrib, 2024). Similar findings have been reported by

Mensi et al. (

2021) and

R. Aly et al. (

2023), who note that food price convergence in emerging markets often occurs slowly due to structural supply constraints rather than exchange rate volatility alone.

Climatic variables play a substantial role in shaping food price dynamics. The significant and positive long-run coefficient of precipitation (L_PR) confirms that favorable rainfall improves agricultural output and mitigates inflationary pressures, consistent with

FAO (

2023a) and

Moessner and de Haan (

2022), who highlight climate variability as a central determinant of price volatility in North Africa. The influence of temperature (TP), although statistically weaker, suggests that prolonged heat episodes may exacerbate price volatility through yield losses and water scarcity. These findings align with Morocco’s increasing exposure to climate stress, reinforcing the need for resilient agri-food and water management strategies (

World Bank, 2023).

From a structural perspective, the inclusion of dummies capturing major shocks (S2018, S2020, S2022) demonstrates the macroeconomic sensitivity of food prices to global disruptions. The 2018 exchange rate band widening had a mild stabilizing effect, confirming that gradual liberalization did not trigger excessive volatility—a result consistent with

IMF (

2019) expectations. Conversely, the 2020 pandemic and the 2022 commodity price surge significantly disrupted price stability, emphasizing the vulnerability of Morocco’s import-dependent food system to external shocks. These observations corroborate recent work by

Bouoiyour and Selmi (

2022), who find that external energy and cereal price shocks dominate domestic drivers of inflation in the MENA region.

The absence of long-run or short-run asymmetry in the NARDL results suggests that Morocco’s monetary and exchange rate policy has achieved a relatively balanced transmission mechanism. Both appreciations and depreciations of the dirham produce proportionally similar effects on food prices, likely due to targeted interventions by

Bank Al-Maghrib (

2024) and the presence of price-stabilization policies for essential commodities (

FAO, 2023a). This symmetric response contrasts with findings in more liberalized economies, where exchange rate depreciations tend to exert stronger inflationary effects (

Bahmani-Oskooee & Fariditavana, 2016;

Salisu & Isah, 2018).

Policy implications stem from these observations. First, maintaining a cautious and gradual approach to exchange rate flexibility remains appropriate in the short term. The symmetric and limited pass-through indicates that Morocco’s hybrid exchange rate system successfully balances competitiveness with inflation control. Nonetheless, continued monitoring is necessary to ensure that future band widenings do not amplify volatility in imported food prices. Second, the significant role of precipitation underscores the need for climate-resilient agricultural investment, including water-saving irrigation, cereal diversification, and storage infrastructure, as outlined in the “Génération Green 2020–2030” strategy. Third, as external shocks (notably from global energy and grain markets) remain the dominant inflation drivers, strengthening food import diversification and hedging mechanisms could mitigate exposure to international price spikes.

From a broader macroeconomic standpoint, the findings also support the coordination of monetary and agricultural policies. A proactive communication strategy by

Bank Al-Maghrib (

2025) regarding exchange rate movements, combined with improved market transparency in food supply chains, would help anchor inflation expectations. Moreover, integrating climate risk into inflation forecasting models could enhance the predictive accuracy of policy responses, a recommendation aligned with

OECD (

2023) and

IMF (

2025) guidelines on climate-inflation linkages.

In summary, the study provides empirical evidence that Morocco’s food price inflation is shaped more by climatic and global commodity factors than by asymmetric exchange rate shocks. The current monetary framework has effectively cushioned external pressures without compromising stability. Looking ahead, sustained progress will depend on deepening exchange rate flexibility within a credible inflation-targeting framework, while reinforcing climate adaptation and food security measures to safeguard price stability in the long term.

7. Conclusions

This study investigates the determinants of food price inflation in Morocco using an ARDL(3,0,0,0,2,0,0) model, complemented by an error-correction representation and a battery of robustness diagnostics. The empirical evidence reveals that food prices in Morocco exhibit substantial inertia, with the lagged dependent variable emerging as the strongest and most consistent predictor of short-term dynamics. This pattern mirrors the persistence found in other emerging economies, where structural rigidities, indexation practices, and supply-side constraints slow the adjustment of consumer prices (

Hendry & Juselius, 2000;

Ibrahim, 2015).

In the short run, external shocks such as exchange rate movements, global oil prices, and international cereal prices display limited immediate effects. This muted pass-through reflects Morocco’s managed exchange rate regime, the presence of food subsidies and state interventions, and the importance of domestic supply chains—factors also highlighted in international assessments of inflation in semi-open economies (

Bahmani-Oskooee & Gelan, 2018;

Bank Al-Maghrib, 2024). Import dynamics show a delayed but significant impact, confirming the role of trade-related pressures in shaping food inflation with a lag of one to two months. Rainfall conditions exert a modest but recurrent influence, underscoring Morocco’s sensitivity to climate variability, consistent with empirical findings on weather–food price linkages (

Moessner & de Haan, 2022).

The long-run results confirm the existence of a stable equilibrium relationship between food prices and key macroeconomic and climatic variables. The negative and marginally significant long-run effect of oil prices suggests that energy markets indirectly affect food prices through input and transport costs. Precipitation emerges as the only consistently significant long-run determinant, reinforcing the structural role of agricultural supply conditions in Morocco’s inflation trajectory. The insignificance of the exchange rate in the long run indicates partial insulation from external price shocks, likely due to Morocco’s cereal stockholding strategy, subsidies, and gradual exchange rate liberalization.

The robustness checks—normality assessment, LM autocorrelation tests, Breusch–Pagan–Godfrey heteroskedasticity test, VIF diagnostics, and stability plots (CUSUM and CUSUMQ)—confirm that the ARDL specification is statistically well-behaved. The NARDL framework indicates no asymmetric exchange rate pass-through, suggesting that appreciation and depreciation exert similar effects on food prices. This symmetry validates the baseline linear ARDL structure and supports the interpretation that Morocco’s food price system remains primarily driven by domestic inertia, climate conditions, and delayed import dynamics rather than directional exchange-rate shocks.

Overall, the findings emphasize that policies aimed at stabilizing food inflation in Morocco should prioritize strengthening agricultural resilience, mitigating climate-related volatility, ensuring efficient import management, and preserving macroeconomic stability. While exchange rate flexibility remains relevant, its direct influence on food inflation appears limited relative to structural and climatic determinants. Future research may extend this work by incorporating high-frequency climate indicators, commodity futures markets, or sector-specific supply chain disruptions to capture additional sources of volatility.