1. Introduction

Background: Technology advancements have facilitated people’s lives over the past decades, leading to the prevalence of cashless, electronic, and online payments in the financial sector. However, these advancements in financial sectors have been accompanied by a rise in various forms of fraud and scams, such as identity theft, account takeover, card skimming, phishing, money laundering, and cyberattacks (

Vashistha & Tiwari, 2024). Most fraudulent activities result in financial losses, causing substantial harm to financial institutions, individuals, and organizations. These losses also escalate operational risk, a key category defined by the Basel Framework, a comprehensive set of measures to strengthen the regulation, supervision, and risk management of the global banking sector (

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, 2024). Consumers in the United States lost more than USD 10 billion to fraud, marking a 14% increase from 2022, according to statistics of the Federal Trade Commission of the USA (

Federal Trade Commission, 2024). In 2023, AUD 2.7 billion was stolen by scammers from Australian consumers (

The Treasury, 2024). Although these financially external frauds emerged over a decade, they consistently pose a huge threat to the world’s economy and society’s well-being as people are more dependent on the digital world during the COVID and post-COVID era. Inadequate regulatory oversight concerning this risk could even result in severe breakdown for banks and financial institutions. Capital requirements, such as those based on Risk-Weighted Assets (RWA) within the Basel Framework, manage risk by ensuring banks maintain sufficient capital buffers. Complementing this, effective fraud detection strategies are imperative to tackle operational risk directly, minimizing financial losses and protecting customers from harm.

Motivation and Purpose: Machine Learning (ML), along with its subset Deep Learning (DL), is widely leveraged by researchers and practitioners to build fraud detection systems because of its effectiveness in prediction and forecasting by identifying intricate patterns and learning historical behaviors from large volumes of data (

Dal Pozzolo et al., 2014). However, interpretability of “Black Box Model”, data imbalance, data inaccessibility, and misclassification are common challenges in financial fraud detection by ML (

Abdul Salam et al., 2024;

Ahmed et al., 2025;

Baisholan et al., 2025b;

Tayebi & El Kafhali, 2025). This study aims to survey recent ML methods applied to financial transaction fraud detection—which work by forecasting the probability of fraud to mitigate financial risk—and to evaluate their progress and weaknesses. Although several similar reviews (

Baisholan et al., 2025a;

Chen et al., 2025;

Hafez et al., 2025;

Moradi et al., 2025) were released recently, making substantial progress in this field, they still suffer from certain limitations. These include a lack of focus on transaction fraud detection specifically, insufficient discussion of preprocessing strategies, and a failure to address financial implications or link them systematically to financial risk, etc. Our work will distinguish itself from existing reviews by addressing these research gaps (

Table 1).

Specifically, we are going to provide a critical analysis of ML techniques for transaction fraud detection, structured thematically to address advances, challenges, and opportunities. This analysis encompasses their classification methods, preprocessing strategies, highlights, results, and limitations. Additionally, we will conduct a deeper evaluation of preprocessing strategies. Moreover, we intend to emphasize the financial implications and significance of these methods from the perspective of the financial sector. This will involve aspects such as financial metric design, feature explainability, time-series considerations, and financial data privacy. By linking our analysis to risk management and regulatory compliance, we aim to bridge a critical research gap: few studies have systematically addressed the financial impact when applying ML to detect transaction fraud, despite it being a problem rooted in the financial sector itself. The overall goal is to provide a comprehensive review of recent ML methods in handling transaction fraud detection and to offer insights into future directions for both researchers and practitioners in this field.

Scope: This research primarily focuses on peer-reviewed journal articles and conference papers from the past seven years (January 2018–October 2025) that employ ML algorithms to detect card transaction fraud, a specific form of external fraud in operational risk under the Basel Framework. Since financial transaction data is usually structured, the datasets used among selected studies are tabular. They include features such as transaction time, amount, receiving account, type of transaction, age group, monthly salary, etc. The target is a binary feature (typically labeled 0 or 1) that indicates whether a transaction is fraudulent, defining the classification task.

This study contributes to the literature in the following key ways:

We assess recent ML progress in transaction fraud detection for financial risk, using a structured taxonomy that covers advances and limitations to provide a comprehensive domain overview.

Simultaneously, we specifically evaluate preprocessing methods, including data balancing, feature engineering, and hyperparameter optimization techniques, which are critical for enhancing ML performance in classification tasks, emphasizing a potential future focus.

Comparisons across studies by aggregation are conducted to critically analyze our reviews, presenting key findings.

Additionally, we address the financial implications and significance of these methods, linking them to risk management.

Finally, the review concludes with a comprehensive discussion of the limitations and future scope of current studies, highlighting directions for further work by researchers and practitioners in this domain.

The rest of the study is arranged in the following way:

Section 2 briefly explains the review methodology employed to conduct this research. In

Section 3, we review and analyze these approaches in-depth based on four subthemes: Traditional ML, DL, Ensemble method, and Hybrid method. Key topics such as dataset descriptions, preprocessing strategies, and cross-validation are considered. Discussions on performance comparisons across our reviews are carried out.

Section 4 discusses the financial implications, closely connected to risk management.

Section 5 focuses on gaps and limitations in this domain and provides future directions. In

Section 6, we conclude this study.

2. Review Methodology

In this study, we perform an exhaustive and rigorous evaluation of the most recent publications on financial risk detection in the context of card transaction fraud using state-of-the-art ML. To ensure the quality of our evaluations, we referred to some of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (

Page et al., 2021) and Kitchenham Systematic Review Process guidelines (

Kitchenham & Charters, 2007). Detailed steps are described in the following.

Initially, a comprehensive search was conducted using a combination of keywords: (“credit card fraud detection” OR “transaction fraud detection” OR “financial fraud detection”) and (“machine learning” OR “deep learning”). These search queries were applied to databases including Google Scholar, Springer Nature Link, ScienceDirect, Scopus, and IEEE Xplore to search publications published from January 2018 to October 2025. Then publications between the first five and ten pages of the search results in the above databases were screened. In addition, we conducted another search in terms of the above keywords on Google Scholar from January 2024 to October 2025 and browsed publications of the first ten pages to ensure our reviews keep up with the times. Only studies written in English and published in peer-reviewed journals or conferences were considered.

After screening 200 publications with their abstracts, experimental results, and summaries, we selected 41 publications for further in-depth reviews. Our selection criteria include relevance (whether the method is a Machine Learning based algorithm and applied to financial transaction/credit card fraud datasets), citation times according to Google Scholar, journal quality, etc. Specifically, studies that did not employ ML/DL techniques or that were not focused on transaction fraud detection with tabular data were excluded. In addition to satisfying the relevance, publications must also meet the following: (citation times > 50) OR (journal indexed in SCI with IF > 1.5) OR (journal indexed in ESCI with IF > 1.5). First, a minimum of 50 citations, a benchmark for influential work, ensured the credibility and impact of selected work. Second, to mitigate the recency bias in citation counts, we included papers from journals with an Impact Factor (IF) > 1.5, a threshold that captures quality emerging research while maintaining a baseline of editorial rigor. We also conducted snowballing through Research Rabbit to scan the reference lists of selected publications to find other related studies, but no additional publications were selected according to our selection criteria and their publishing years. To ensure the quality of included papers, the following components were assessed and satisfied by all selected works:

Data & Reproducibility: Datasets are clearly described, and a source link is provided if publicly accessible.

Experimental Rigor: The methodology and experimental steps are explicitly stated.

Model Credibility: The proposed model is compared with baselines or prior work.

Analysis: The results are discussed and analyzed.

With organized reviewing, we gathered information from the 41 selected publications, including their years, journals published, citation times (Google Scholar), methods used/developed, data balancing techniques, feature engineering techniques, datasets used, highlights, results, limitations/challenges, and financial significance, extracting and categorizing all the information into an Excel form. ML used to be categorized into two groups: Supervised Learning and Unsupervised Learning. But in financial fraud detection, no matter what preprocessing strategies (Supervised, Unsupervised, Statistical, or others) are employed, the last step is usually classification, which is a type of Supervised Learning. Thus, it is meaningless to classify in the traditional way since all these fraud detection techniques can be categorized as Supervised Learning (

Chhabra et al., 2023). Alternatively, we established a taxonomy in terms of the specific ML strategies employed and divided them into four subgroups: Traditional ML, DL, Ensemble, and Hybrid. The fundamental distinction among them lies in their core mechanisms: from human-driven feature engineering (Traditional ML) to automatic feature learning (DL), to collective prediction (Ensemble), and finally to integrative system design (Hybrid). Each subgroup was reviewed in depth, and its strengths and limitations were thoroughly described to enlighten future studies.

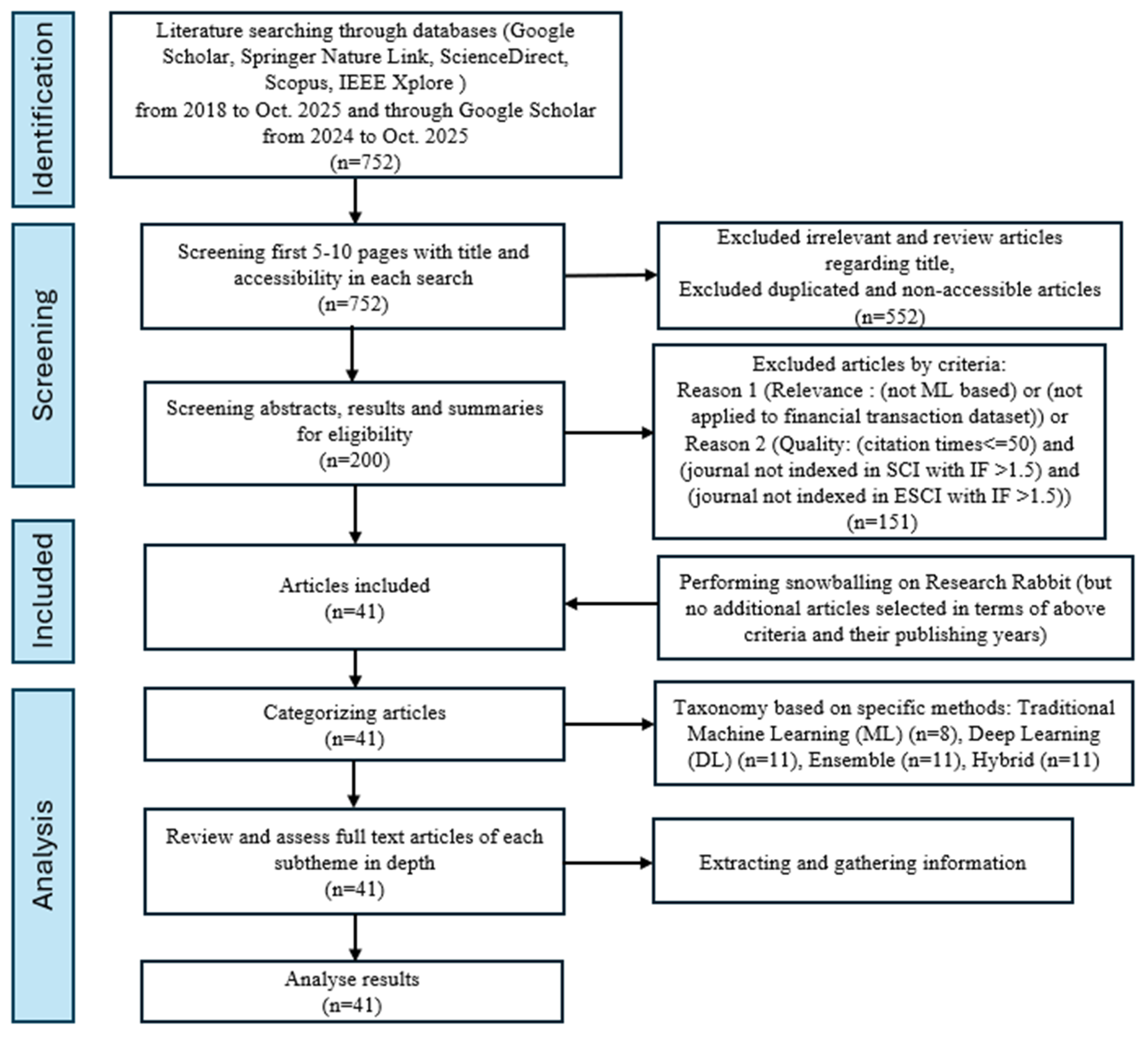

A full review process diagram can be seen in

Figure 1. The workflow of identification, screening, and inclusion ties closely to the framework of PRISMA and Kitchenham to ensure the trustworthiness of our research. Furthermore, an analysis part following the inclusion is presented in the workflow, providing readers with a clear understanding of the overall evaluation process. Through the proposed methodology, a comprehensive study is performed to present various ML techniques employed in financial risk prevention, with a particular focus on transaction fraud detection.

3. Analysis of Approaches

ML has been widely adopted in the financial domain to solve practical problems, like financial fraud and transaction fraud, particularly where this research focuses. Overall, the number of papers has increased over time. In

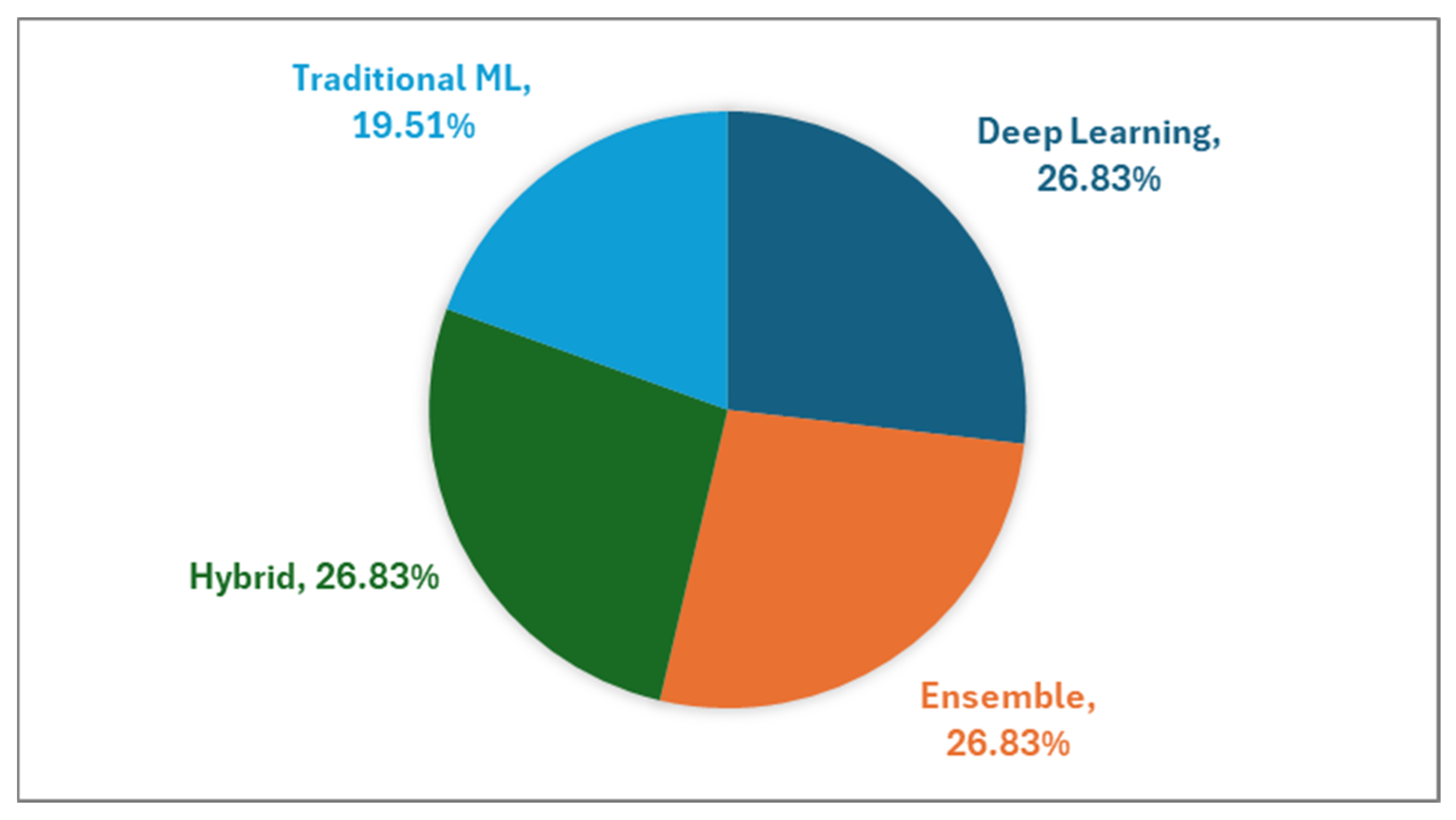

Figure 2, the four methods used are almost evenly distributed, with DL, Ensemble, and Hybrid slightly higher than Traditional ML in our reviewed papers. It suggests that DL, Ensemble, and Hybrid methods attract more attention than Traditional ML in transaction fraud detection.

3.1. Traditional Machine Learning (ML)

Traditional ML refers to algorithms such as Logistic Regression (LR), Naïve Bayes (NB), K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Decision Tree (DT), etc., which are generally less complex, more interpretable, and perform well with smaller datasets. LR provides a linear, probabilistic foundation by modeling outcomes with a logistic curve, while NB relies on probability and the assumption of feature independence to perform quick probabilistic classification. In contrast, KNN is an instance-based, non-parametric method that classifies data points based on the majority vote of their k closest neighbors in the feature space. DT uses a hierarchical, rule-based structure to split data recursively, creating an interpretable model for classifications or predictions. In this subsection, we incorporate publications if they include any of the traditional ML methods mentioned above. Thus, the traditional ML subgroup comprises publications that may include both traditional ML and other types of methods.

Three traditional ML algorithms, including LR, NB, and KNN with Random Under Sampling (RUS), were employed by

Itoo et al. (

2021) to detect card transaction fraud. In this study, LR outperformed NB and KNN with a maximum accuracy of 95%. This result indicates that LR shows optimal performance when processing fewer data samples, reduced by RUS. Another study (

Tanouz et al., 2021) compared Random Forest (RF), DT, LR, and NB with RUS resampling. RF, composed of multiple decision trees that output a mean prediction, achieved the best result with a recall of 91.11% due to its inherent ability to reduce overfitting. Although these 2 studies demonstrate excellent performance of Traditional ML models on transaction fraud detection, the reduced training data resulting from RUS may negatively impact the model’s stability and generalizability.

Both studies (

Ileberi et al., 2022;

Mienye & Sun, 2023b) introduced Genetic Algorithm (GA) with Traditional ML models on the same dataset. IG-GAW (

Mienye & Sun, 2023b), which uses Extreme Learning Machine (ELM) as its classification method and achieves a sensitivity of 99.7%, outperforms GA-RF (

Ileberi et al., 2022), which uses RF with a sensitivity of 72.56%. Due to its simpler learning process and robust generalizability, the ELM—a feedforward neural network that uses randomly fixed hidden weights and analytically solves output weights—demonstrates superior capability over RF in this case.

Afriyie et al. (

2023) revealed the weakness of RF in their study, showing that it achieved low performance in terms of F1-score and precision, with only 17% and 9%. This performance would inconvenience customers, subsequently raising operational costs and risks for financial institutions if deploying the model to a real-time system. All reviewed publications associated with Traditional ML are comprehensively summarized in

Table 2.

3.2. Deep Learning (DL)

DL is a subset of ML but is more complex and usually adopts multilayer neural network architectures to learn the intricate patterns from vast amounts of data. A detailed review is listed in

Table 3 at the end of this subsection.

Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) with 20 layers achieved an accuracy of 99.9%, an F1-score of 85.71%, a precision of 93% and an AUC of 98% (

Alarfaj et al., 2022) while Continuous-Coupled Neural Network (CCNN) with Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) achieved an accuracy of 99.98%, a precision of 99.96%, a recall of 100%, and an F1-score of 99.98% (

Wu et al., 2025). CNN was designed to automatically extract spatial features from image data via convolutional layers with learnable filters, while CCNN improved the representation of intricate spatiotemporal patterns by continuous neuron activation and dynamic coupling. These strong results demonstrate their efficacy in processing financial transaction data.

Yu et al. (

2024) adopted the Transformer model, a deep learning architecture originally developed for natural language processing tasks on financial transaction datasets. The transformer model with a multi-head attention mechanism successfully captured the intricate correlations between attributes of financial transaction datasets and obtained a recall of 99.8% and an F1-score of 99.8% under cross-validation. These state-of-the-art DL algorithms, particularly CCNN and Transformer, demonstrated impressive performance due to their inherently robust architectures. However, the substantial computational resources required for training and classifying, along with challenges in interpretability, hinder these methods from becoming the most effective solution for mitigating financial risks associated with transaction fraud in real-world systems.

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) captured researchers’ interests in transaction fraud detection (

Cherif et al., 2024;

Harish et al., 2024;

Khaled Alarfaj & Shahzadi, 2025). In the financial fraud context, unlike other techniques that only consider single transactions, GNNs usually transform tabular datasets into graphs with customer nodes and merchant nodes and link nodes to uncover the intricate relations and behavior patterns between customer (transaction initiator), merchant (transaction receiver), and transactions before classification. GNNs with lambda architecture—which processes large-scale data through a combined batch and real-time structure—achieved an F1-score of 80.78% and a recall of 79.68% (

Khaled Alarfaj & Shahzadi, 2025). In contrast, GNNs with Relational Graph Convolutional Network (RGCN), used to learn node representations, achieved a lower F1-score of 61% and a recall of 46% (

Harish et al., 2024).

Cherif et al. (

2024) proposed an encoder–decoder-based GNN model to detect transaction fraud. The encoder–decoder architecture was applied to represent the nodes, and the proposed model yielded better results than the previous two studies, achieving a recall of 92%, an F1-score of 86%, and an AUC of 92%. Overall, GNNs demonstrate lower performance relative to other DL algorithms. The effectiveness of GNNs in transaction fraud detection needs further investigation, as poor performance may lead to increased operational risk.

3.3. Ensemble Method

Ensemble methods are learning algorithms that construct two or more classifiers (also called weak learners) and then classify new data points by averaging, stacking, or taking a (weighted) vote of their predictions (

Dietterich, 2000). They balance bias and variance of weak learners and usually yield a more robust result, improving overall performance compared to any single constituent model. Ensemble could be a powerful tool to combat financial risk in the context of transaction fraud.

The voting ensemble, which outputs classification results by aggregating (hard or soft) votes from multiple weak learners, has drawn attention in transaction fraud detection. All the work (

Ahmed et al., 2025;

Chhabra et al., 2023;

Khalid et al., 2024) achieved promising accuracy (exceeding 99.9%) on the same dataset by employing a voting ensemble composed of different base classifiers. Another study (

Talukder et al., 2024) proposed a voting-based multistage ensemble ML classifier (EIBMC), leveraging the diversity of the fundamental ML models and combining the finest aspects of multiple multistage ensemble models into a more robust and trustworthy detection technique. EIBMC achieved an accuracy score of 99.94% and an AUC score of 100% under stratified 5-fold cross-validation. However, EIBMC used accuracy—a metric known to be biased in imbalanced datasets—to assign weights to its ensemble classifiers. For future work, metrics like recall could be adopted to improve model robustness.

A cost-sensitive and ensemble deep forest (CE-gcForest) method, inspired by

Zhou and Feng (

2019), was employed to detect transaction fraud (

Zhao et al., 2023). The ensemble-gcForest model enhances diversity and improves performance by selecting the best-performing base-classifiers in each round based on their Type II error rate. This process results in a more robust and efficient ensemble. The model achieved the best performance compared to other baseline ML models, with AUC 98.01% and 98.25% respectively, on real-world datasets.

Mienye and Sun (

2023a) implemented a stacking ensemble approach involving deep learning base-classifiers, Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU), and a meta-classifier, Multilayer Perception (MLP), to address the problem of dynamic patterns in card transactions. In a stacking ensemble, the base classifiers are trained on the original features, and the meta-classifier is trained on the results of the base classifiers to produce the final output. The proposed model obtained promising results with a recall value of 100%, a precision value of 99.7% and an AUC value of 100% under a 10-fold cross-validation technique.

The examples discussed above highlight the outstanding proficiency of Ensemble in detecting transaction fraud. Leveraging the strengths and diversities of multiple base learners, Ensemble successfully enhances models’ performance, making them particularly effective in handling complex and unbalanced datasets commonly found in financial transactions. A comprehensive summary regarding the reviewed Ensemble methods can be found in

Table 4 below.

3.4. Hybrid Method

Unlike Ensemble methods, which combine the predictions of multiple base learners, Hybrid methods integrate two or more ML algorithms sequentially or in parallel to exploit their individual strengths. They are used for tasks such as parameter optimization, feature engineering, data balancing, and classification. This architecture allows a more robust, accurate, and reliable model to be developed.

Du et al. (

2024) employed an Autoencoder (AE) for feature learning and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) for classification, achieving a recall of 89.29%. Here, the AE compresses input data to extract features, while XGBoost serves as the predictive ensemble model. Another hybrid deep learning architecture, the Zeiler and Fergus Network integrated with Dwarf Mongoose–Shuffled Shepherd Political Optimization (DMSSPO_ZFNet), was proposed (

Ganji & Chaparala, 2024). In this model, feature fusion is performed using Wave Hedge distance and a Deep Neuro-Fuzzy Network (DNFN), hyperparameters are optimized via DMSSPO, and classification is handled by ZFNet. It achieved an accuracy of 96.1%, a sensitivity of 96.1%, and a specificity of 95.1%.

Meta-heuristic algorithms inspired by animal behaviors have recently gained popularity for optimizing hyperparameters in transaction fraud detection.

Jovanovic et al. (

2022) introduced Group Search Fireflies algorithms (GSFA) coupled with XGBoost to detect transaction fraud. The GSFA utilizes a fitness function based on firefly brightness and attraction. It also employs a disputation operator, which searches for solutions within a selected subgroup of the population to optimize the hyperparameters of ML algorithms. XGBoost-GSFA achieved a recall of 99.97%, an F1-score of 99.97%, and an AUC of 100%.

Reddy et al. (

2025) introduced XGBoost with Elephant Herd Optimization (EHO) to tune hyperparameters. EHO finds an optimal hyperparameter set by mimicking elephant herding behavior, guided by specific evaluation metrics. The result showed XGBoost with EHO had an accuracy of 98% and an AUC of 99.7% under 20-fold cross-validation.

These statistics indicate that the capability of Hybrid techniques on transaction fraud detection is exceptional. Meta-heuristic algorithms, in particular, which are more flexible and more efficient at finding near-optimal solutions and less prone to becoming stuck in local optima, show a superior ability to enhance ML models’ performance through hyperparameter optimization. Nevertheless, most Hybrid methods incorporate deep neural network structures, resulting in the same issues as DL, like interpretability and requiring intensive computing resources.

Table 5 presents the review summary of the Hybrid method.

3.5. Analysis

3.5.1. Datasets Description

Datasets for detecting transaction fraud are usually collected in two ways: online open sources or private data from banks or financial institutions. Most researchers adopt online open-source data to build their ML models on card transaction fraud detection, since private data from banks is inaccessible in most cases due to the private nature, while in some reviewed studies, researchers cooperate with banks and financial institutions so that they can access real-world data to build detection systems.

Online open-source data:

The European credit card dataset is a highly adopted dataset to train ML models in transaction fraud. There are two versions, which were made in 2013 and 2023, respectively. The first version contains 284,807 transactions, where 492 out of 284,807 (0.172%) transactions are fraudulent, made by European cardholders in September 2013 (

ULB Machine Learning Group, 2018). The second version contains 550,000 credit card transactions, which are evenly distributed and made by European cardholders in 2023 (

Elgiriyewithana, 2023). Most features in these datasets are transformed by Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and anonymized due to privacy concerns.

The Sparkov dataset is used by several studies. It was simulated using the Sparkov Data Generation tool, covering credit cards of 1000 customers doing transactions with a pool of 800 merchants from the duration 1 January 2019 to 31 December 2020 (

Shenoy, 2022). This dataset is highly unbalanced.

The BankSim dataset is a synthetic dataset of bank payments based on a Spanish bank. It contains 594,643 records in total and is highly unbalanced, with normal payments of 587,443 and fraudulent transactions of 7200 (

Lopez-Rojas, 2017a).

The PaySim dataset is another synthetic dataset generated from a private dataset containing mobile money transactions in an African country to solve the lack of publicly available datasets in financial fraud (

Lopez-Rojas, 2017b). This dataset is very huge, containing more than 6 million instances, and is highly unbalanced.

Private data:

Private data from banks or financial institutions often contains real-world transactions. ML models developed with real-world data are usually more efficient and accurate because real data preserves all the authentic information of transactions. However, private data is hard to access due to the private nature of financial security.

Table 6 provides a summary of the datasets used in the reviewed papers. As shown, the European credit card dataset is most welcomed, and the adoption times are substantially greater than other datasets. This is because the European credit card dataset is easily accessible and the attributes have already been processed by PCA, providing researchers with clean and standardized data to develop their models (

Chen et al., 2025).

Although synthetic datasets offer valuable utility, they might introduce significant risks in transaction fraud detection (

Tayebi & El Kafhali, 2025). Firstly, synthetic data may fail to capture the complex and non-linear interactions and subtle behavioral cues presented in real-world transactions. Moreover, it often lacks the rare and evolving attack patterns that define emerging fraud. Consequently, models that perform well in training or testing might fail when deployed on different, more complex real-world datasets. Access to rich, up-to-date real transaction data, therefore, remains essential. Real data provides the ground truth needed to validate models, capture live threat intelligence, and ensure that detection systems adapt to novel fraud schemes in real time, thereby maintaining both robustness and regulatory credibility.

3.5.2. Preprocessing

Preprocessing plays a crucial part in ML-based applications before training and classification, especially in financial fraud detection, which typically involves datasets with unbalanced classes and redundant features. Regardless of the ML algorithms implemented, most of the reviewed papers adopted at least one of the three preprocessing methods: data balancing, feature engineering, or hyperparameter tuning/optimization to enhance the performance of their ML models. This subsection provides an analysis of these methods applied by selected publications.

Data Balancing

Data resampling is the most popular choice for researchers to address issues of highly unbalanced datasets in transaction fraud detection. It can create a more balanced data distribution, consequently leading to better model performance. Traditional resampling techniques include undersampling, oversampling, and a combination of undersampling and oversampling, which usually generate synthetic data instances of the minority class or reduce the instances of the majority class by statistical methods (

Alfaiz & Fati, 2022). RUS, Random Over Sampling (ROS), and SMOTE are widely adopted traditional resampling methods. RUS reduces the majority class by randomly removing instances, while ROS randomly duplicates existing minority class instances. SMOTE can generate new synthetic examples of the minority class by interpolating between existing minority instances.

Dang et al. (

2021) compared the model performance with and without SMOTE, concluding that ML models achieve high performance when resampling methods are applied to both of training and testing datasets, but poor results are obtained by applying resampling methods only to the training dataset. However, oversampling can introduce noise and result in overfitting, while undersampling may result in the loss of information (

Cherif et al., 2024). ML methods are alternatives for data resampling, and their generations are usually more robust and credible.

Zheng et al. (

2018) constructed a Hybrid method, Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) with Gaussian Mixture Models (GMMs) to generate transaction samples. In this architecture, generator networks integrated with GMMs create and validate synthetic fraud samples, resulting in a more robust generation process. The result in a real-world system showed strong financial significance. Similarly,

Tayebi and El Kafhali (

2025) leveraged an Autoencoder (AE) coupled with a Support Vector Machine (SVM) in their Hybrid model for data creation and verification. SVM is a traditional supervised ML method that finds the optimal separating hyperplane by maximizing the margin between classes for linear classification and efficiently handles non-linear problems using the kernel trick. In this combined approach, newly generated fraud data points from AE were added to the dataset only if they were correctly classified by the SVM model. This approach yielded promising results, with 99.99% accuracy, 98% precision, 99.99% recall, and a 97.77% F1-score. The validation process in these two examples demonstrated robust data generation.

Assigning class weights that are inversely related to the class frequencies is another alternative to solve the class imbalance (

Alharbi et al., 2022;

Baisholan et al., 2025b;

Cherif et al., 2024;

Zhao et al., 2023). This strategy is preferred because it maintains a realistic distribution to prevent overfitting and avoids biased results caused by artificially generated samples of the minority class (

Cherif et al., 2024).

Zhao et al. (

2023) employed cost-sensitive gcForest to address the data imbalance issue by assigning higher classification costs to fraud cases, while

Baisholan et al. (

2025b) tuned the threshold and adjusted minority class weight. In these examples, a higher penalty was assigned to the model for misclassifying fraud samples. This cost-sensitive approach increases the model’s sensitivity to fraud during training, leading to better performance on imbalanced classification tasks.

Feature Engineering

Feature engineering is another hot topic in detecting financial fraud by ML algorithms because it enhances models’ performance by removing redundant information and extracting useful information. This is achieved by cleaning and restructuring the data through steps such as selecting the optimal set of features and creating new features through aggregation, decomposition, or interaction of existing variables. The goal is to highlight the underlying patterns and relationships within the data, making it easier for the model to learn effectively, rather than simply feeding it raw or unstructured information.

Zhang et al. (

2021) proposed a feature engineering method, Homogeneity-Oriented Behaviour Analysis (HOBA), inspired and developed from a marketing technique called recency-frequency-monetary (RFM) (

Van Vlasselaer et al., 2015), to extract feature variables by aggregation. RFM analyzes and aggregates variables related to three key customer behaviors: recency (how recently they purchased), frequency (how often they purchase), and monetary value (how much they spend). HOBA is an enhanced version of RFM that formalizes this approach in the financial fraud detection context through a structured aggregation strategy, extracting features based on four components: the aggregation characteristic, aggregation period, transaction behavior measure, and aggregation statistic. This strategy helps the model capture fraudulent transaction patterns. GA, a type of Evolutionary-inspired Algorithm (EA), was introduced to find the optimized feature subsets by computing model fitness (

Ileberi et al., 2022;

Mienye & Sun, 2023b). GNNs were applied to represent the graph nodes (

Cherif et al., 2024;

Harish et al., 2024;

Khaled Alarfaj & Shahzadi, 2025), while an Autoencoder (AE) was implemented for feature extraction and representation (

Du et al., 2024;

Zioviris et al., 2024). All the work mentioned improved their models’ performance by integrating feature engineering. However,

Nguyen et al. (

2020) failed to achieve optimal results without implementing feature engineering, as the features in the datasets had little correlation.

Hyperparameter Tuning/Optimization

Hyperparameter tuning and optimization are the processes of finding the optimal set of hyperparameters to achieve the best possible model performance and play an important role in ML algorithms. Several researchers (

Ganji & Chaparala, 2024;

Jovanovic et al., 2022;

Reddy et al., 2025) applied Hybrid methods, incorporating hyperparameter tuning to enhance performance in transaction fraud detection. (see

Section 3.4) Since huge computing resources are required, the feasibility of implementing it in a real-world system could be tested in the future.

3.5.3. Cross-Validation

Cross-validation is a fundamental statistical technique in ML used to evaluate the stability and reliability of predictive models and prevent overfitting (

Wu et al., 2025). As mentioned before, a few studies employed cross-validation techniques to ensure the robustness of their models. The most common implementation is k-fold cross-validation. In this approach, the dataset is first randomly partitioned into k equal, non-overlapping subsets (folds). The model is then trained and evaluated k times; in each iteration, one subset is held out as the test set while the remaining k-1 subsets are used for training. This process ensures every data point is used for testing exactly once. Finally, the k performance scores are averaged to produce a robust and generalized estimate of model performance (

Zheng et al., 2018). Stratified k-fold cross-validation is a crucial variant. This method ensures each fold (subset) maintains the same proportion of class labels as the original dataset, making it essential for imbalanced classification tasks (

Alfaiz & Fati, 2022).

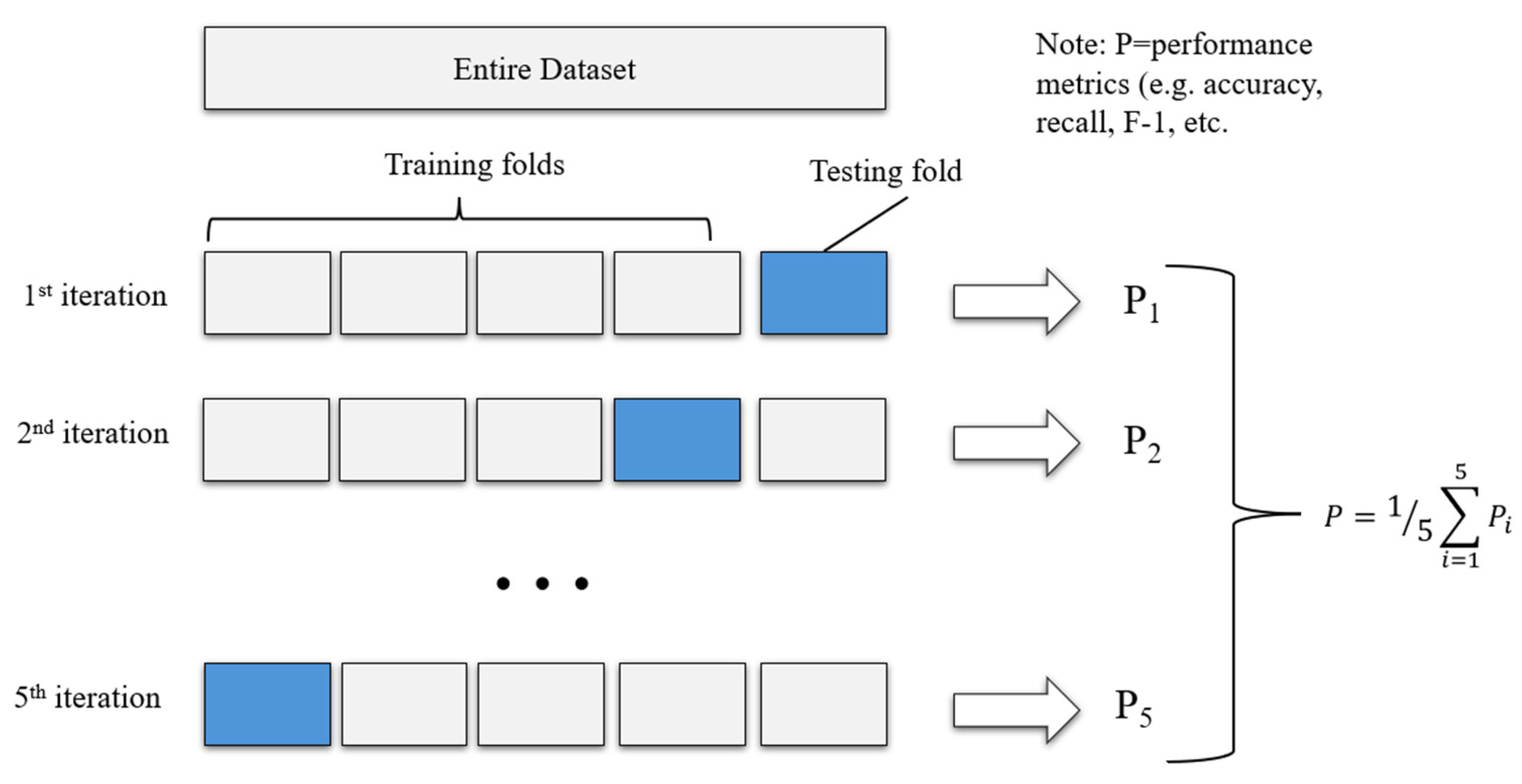

Figure 3 gives an example of 5-fold cross-validation.

3.6. Discussion

We selected several traditional metrics, involving accuracy, recall, precision, AUC, F1-score, and ROC-AUC, that are prevalent to measure the performance of ML models for comparison across studies. The results are presented in

Table 7. As shown, many studies report high accuracy. However, this can be misleading due to severe class imbalance in fraud datasets, as a classifier that always predicts “not fraud” will achieve high accuracy while failing to detect fraud. Several studies show low performance on metrics like recall, precision, and F1-score. This variation in performance is influenced by factors such as the datasets used, preprocessing methods, and the ML models employed.

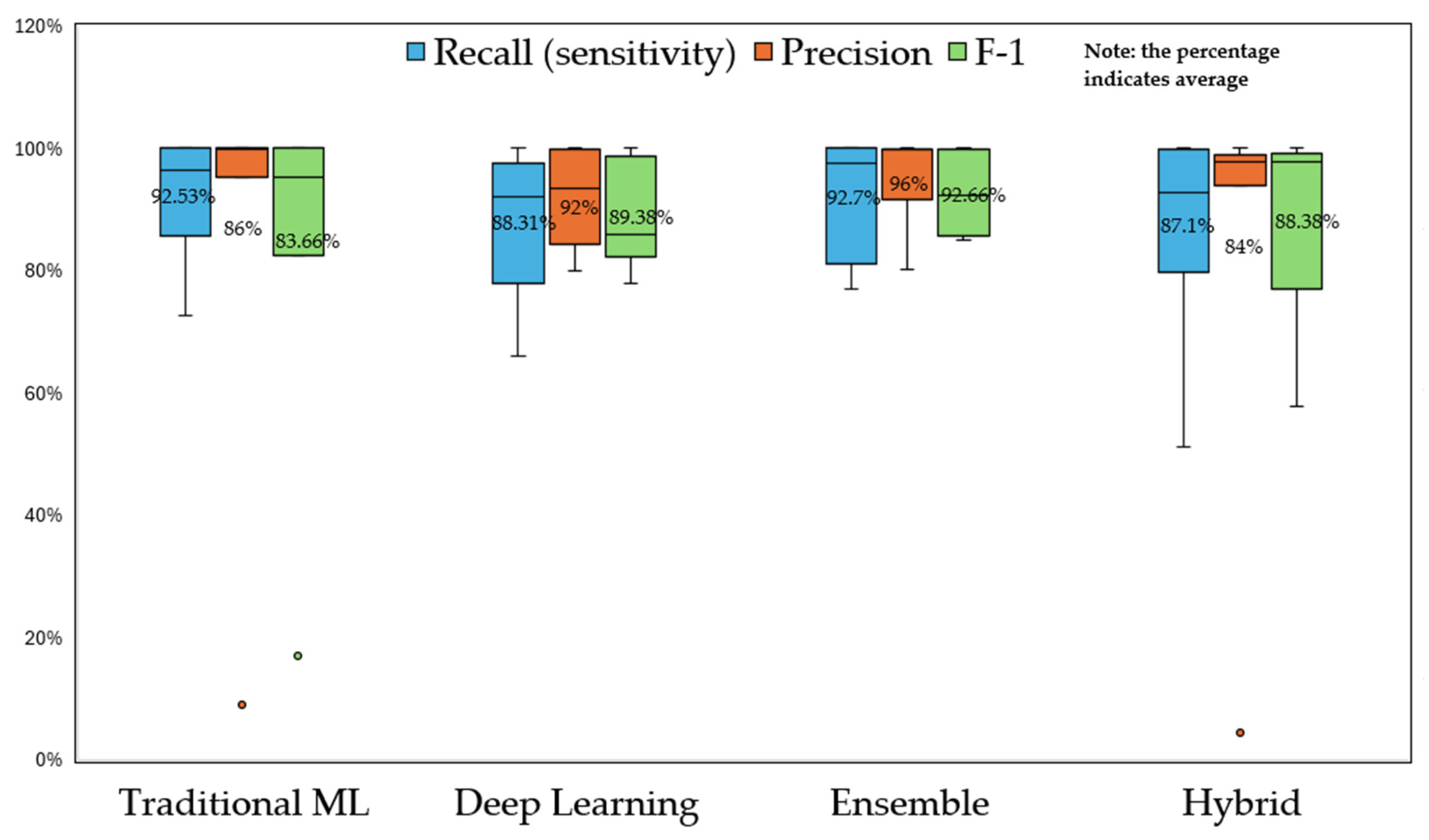

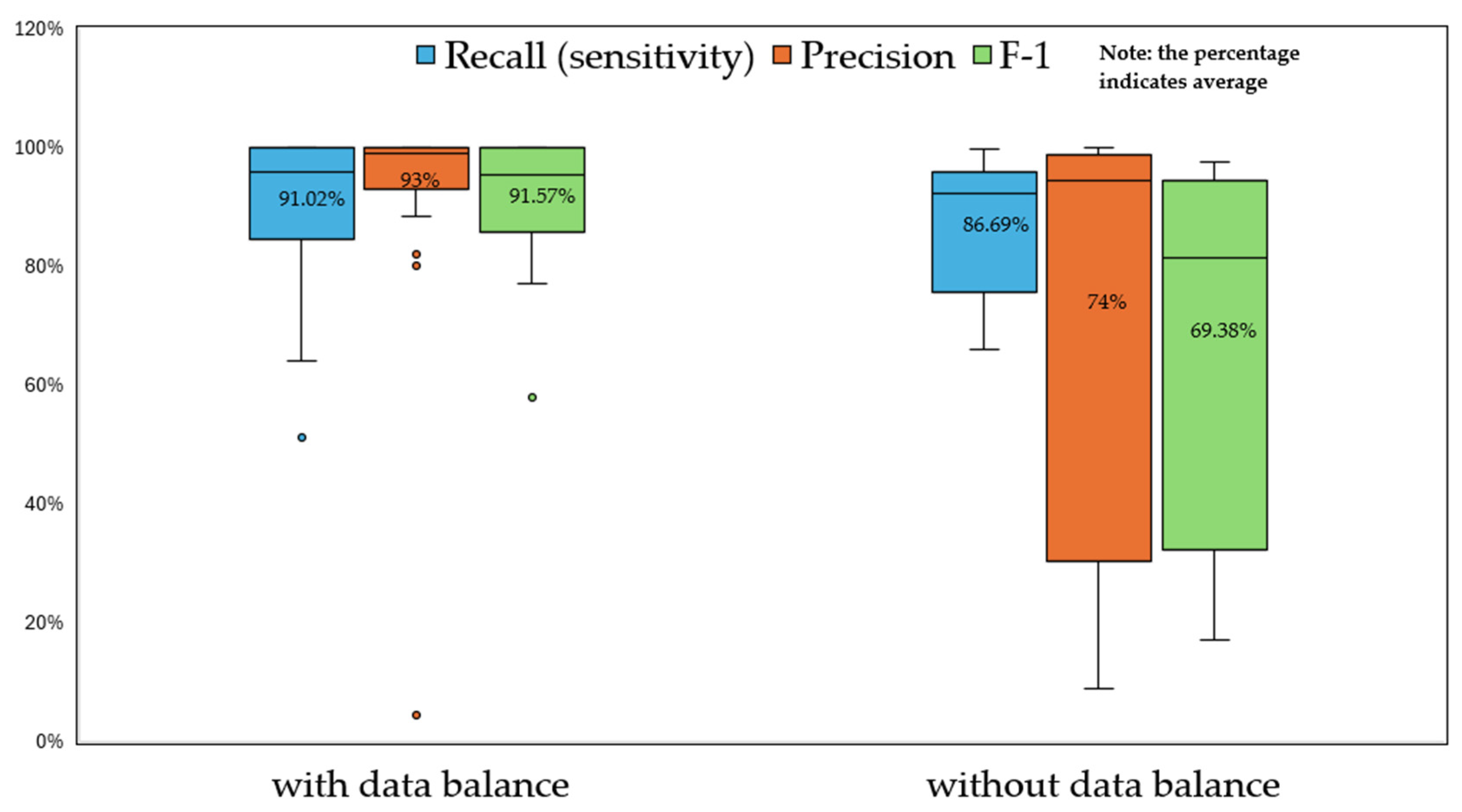

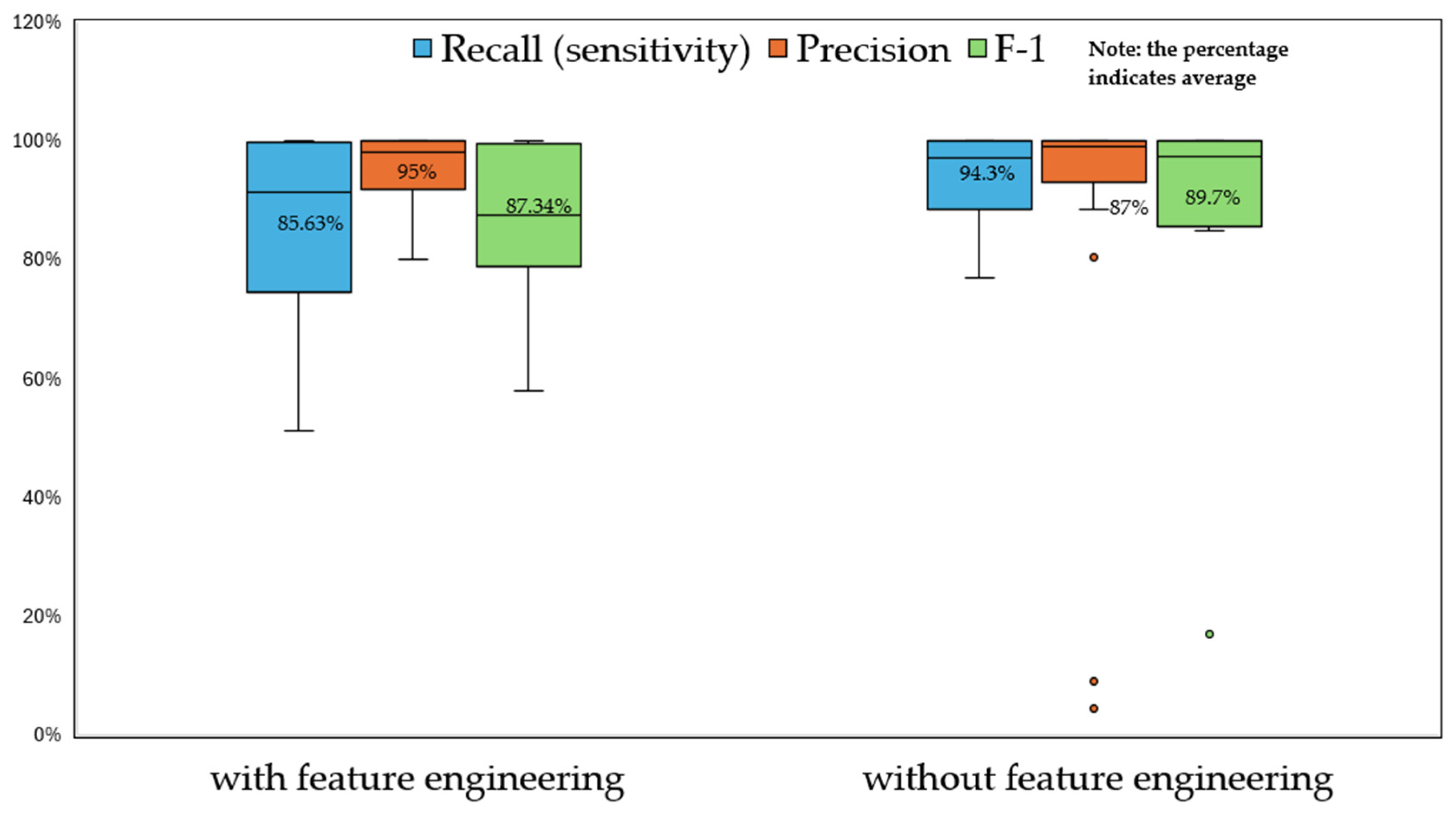

To better understand the performance among various groups, box plots (

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6) with average values are drawn to compare recall, precision, and F1-scoreacross different taxonomies, with and without data balancing and feature engineering (Note: due to insufficient sample sizes within individual datasets, comparisons were conducted across multiple datasets). We chose these three metrics for comparison because more than half of the reviewed work adopted them. Accuracy is excluded since it is unreliable for highly unbalanced binary classification tasks.

Figure 4 presents the results of the comparison across subgroups. As shown, Ensemble outperforms the other three methods according to the average recall, precision, and F1-score. Traditional ML has two outliers while Hybrid has one. F1-score, a comprehensive metric combining precision and recall, provides a balanced view of an ML model’s performance. The graph indicates that Ensemble obtains the highest average F1-score with 92.66%, DL ranks second with 89.38%, Hybrid is slightly lower with 88.38% while Traditional ML has the lowest value with 83.66%. DL, Ensemble, and Hybrid outperform Traditional ML according to F1-score due to their superior powers and more robust architectures to identify intricate patterns. This is consistent with the observation that more studies employ DL, Ensemble, and Hybrid methods for transaction fraud detection compared to Traditional ML approaches.

In terms of

Figure 5, studies that applied data balance techniques demonstrate higher performance overall compared to studies without data balancing, although there are several outliers. The average recall, precision, and F1-scores of studies using data balance techniques are 91.02%, 93%, and 91.57%, respectively, markedly greater than those of studies without data balancing, which are 86.69%, 74%, and 69.38%. This is aligned with the previous observation that data balance techniques are widely adopted by researchers to enhance the performance of transaction fraud detection systems.

In

Figure 6, studies with feature engineering have a higher average precision over studies without feature engineering, which also display some outliers according to precision and F1-score. However, studies without feature engineering show a higher performance in terms of recall and F1-score, contradicting the assumption that feature engineering can improve models’ performance by removing unrelated information and extracting valuable information. One of the reasons might be that inappropriate adoption of feature engineering techniques could lead to poor performance. For example,

Alharbi et al. (

2022) implemented a text2IMG conversion technique, which converted the transactional data with 30 features into 5 × 6-dimensional images for modelling, but the output yielded only 51.22% recall and 57.8% F1-score. The necessity of converting tabular data into images is questionable. Another study (

Malik et al., 2022) employed SVM- recursive feature elimination (RFE) for feature dimension reduction. The process iteratively selects features to identify the optimal subset. However, this approach may eliminate valuable information, resulting in a recall of 64% and an F1-score of 77%. Low recalls would allow more fraudulent transactions to be approved, causing tremendous financial losses and escalating the operational risk. The results of these 2 studies significantly bias the overall average performance of studies with feature engineering. Moreover, several studies (

Khaled Alarfaj & Shahzadi, 2025;

Kim et al., 2019;

Zhang et al., 2021) with feature engineering applied their models to real-world datasets from banks. Their recalls are 80.68%, 91.5%, and 75%, respectively. As we know, real-world data that has better quality is usually more complex than synthetic datasets in transaction fraud. ML models often have lower performance on real-world data than on synthetic data. This could also negatively affect the box plots and overall averages.

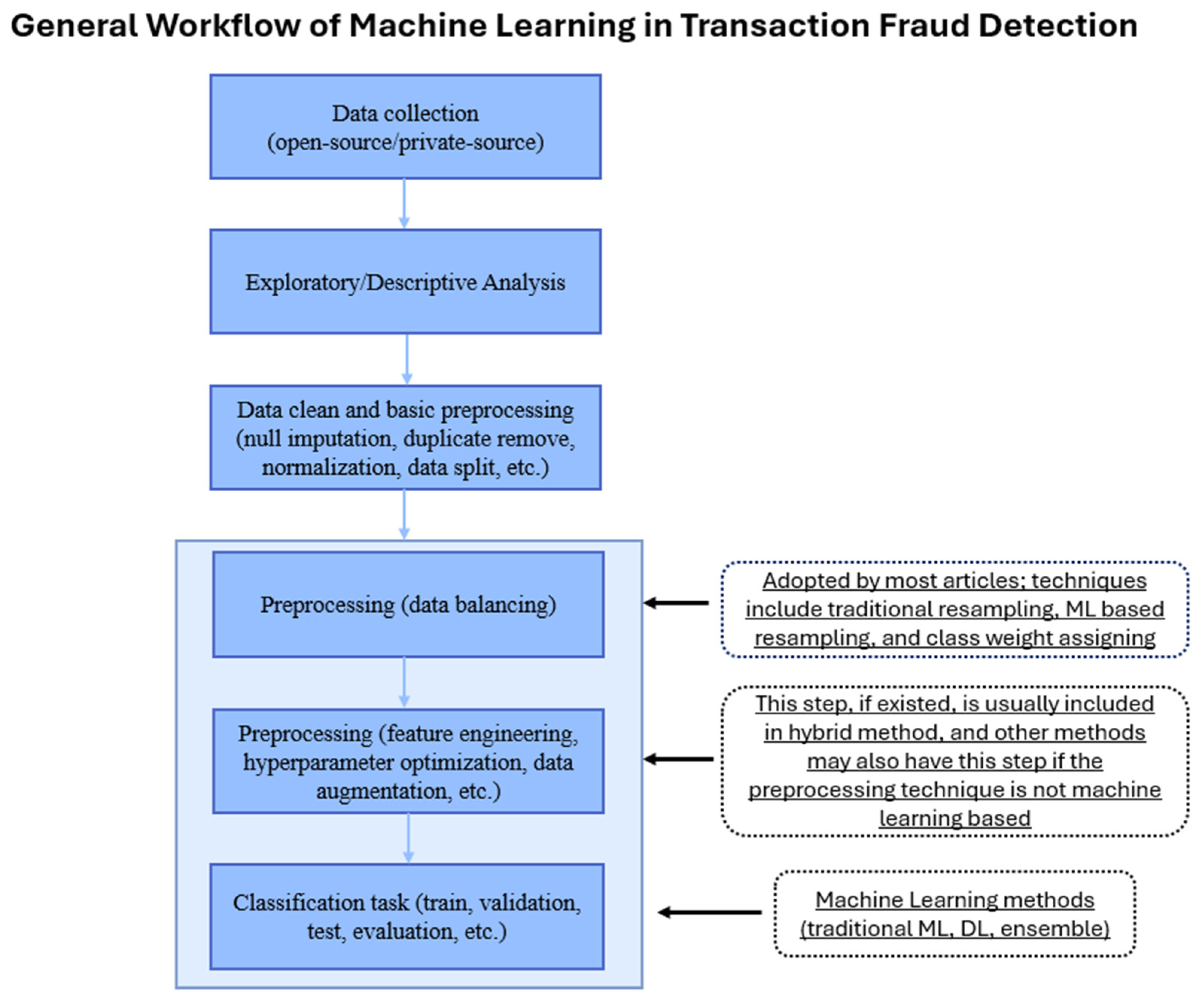

Finally, after comprehensive analysis and exhaustive examination, a general workflow (

Figure 7) of applying ML to mitigate financial risk in the context of transaction fraud detection is developed. One single study may not contain all the depicted steps, but this depiction provides a general picture and helps readers understand the overall process, and key procedures may be incorporated in this domain. The last three steps are considerable, as preprocessing techniques are essential to enhance the model’s performance, and the classification is the final step to predict the possibility of fraud.

5. Limitations/Challenges and Future Scopes

To wrap up, this section extracts limitations and challenges from previous analysis and develops research gaps and future scopes in managing risks associated with detecting financial transaction fraud.

5.1. Limitations/Challenges

An appropriate performance metric might be the most urgent concern in detecting financial fraud by ML for financial institutions. Some studies focus on improving accuracy, a metric that always has a misleadingly high value in unbalanced data classification tasks. Although a higher accuracy marginally reduces losses, it is an indirect and weaker measure than metrics like the F1-score or financial indicators (e.g., CRR, CS), which correlate more directly with actual risk and cost outcomes. Furthermore, since this is fundamentally a financial risk problem, few studies adopted financially significant metrics that assess the cost of fraud under the risk. This is inconsistent with the risk management framework to mitigate financial losses.

Interpretability is another important limitation confronted by all types of ML methods, which are often called “Black Box Models”. This is especially true for DL, Ensemble, and Hybrid methods, which employ more complicated architectures that are difficult to understand. Under the Scam Prevention Framework, identifying individuals who could be impacted by scams is required (

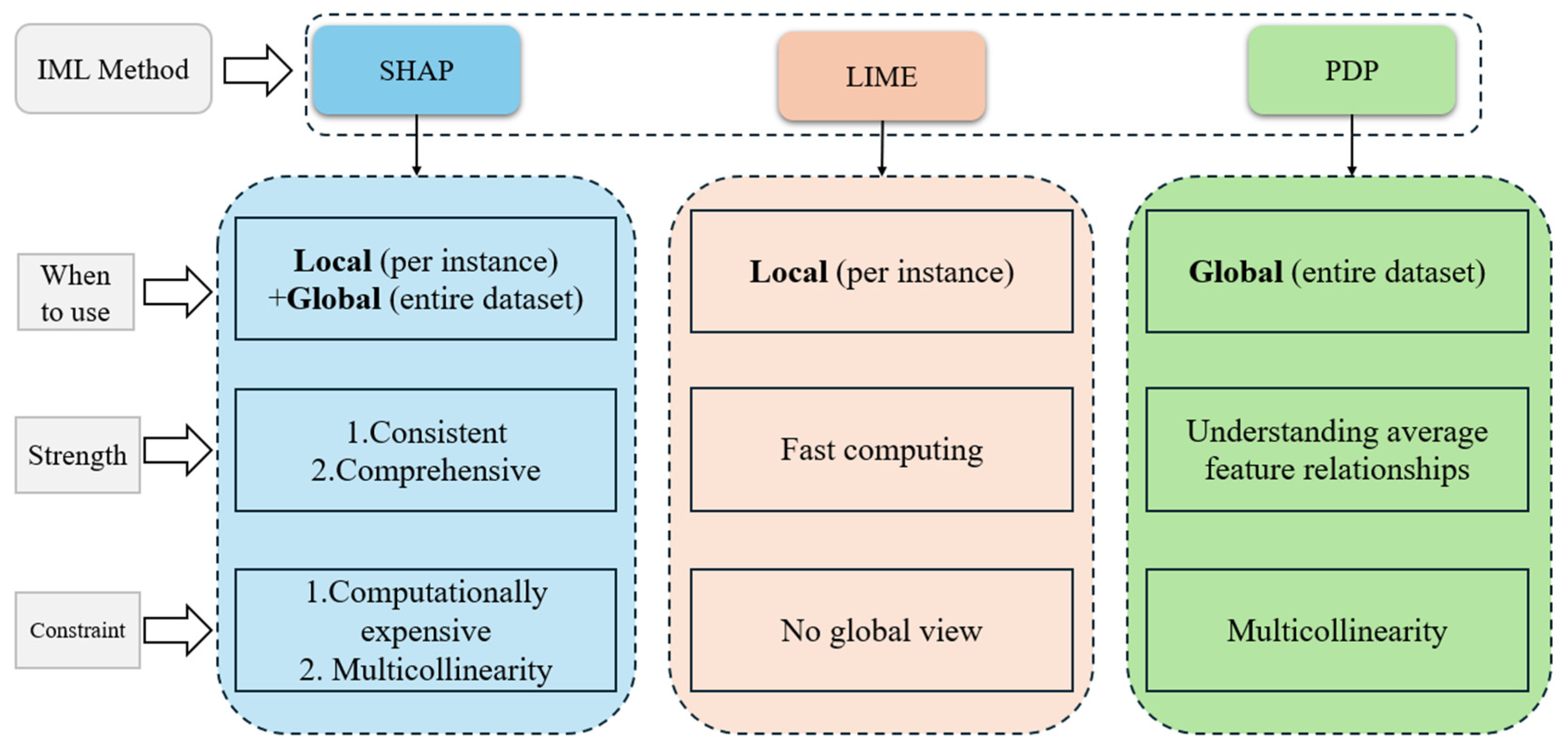

The Treasury, 2024). So, it is important for financial institutions to set up prevention measures by understanding the intricate relationship between features and their contributions to the results. However, only one publication in the review used IML techniques, representing a significant gap in the literature.

Data privacy/availability is one of the biggest obstacles faced by financial fraud detection. Open-source datasets are insufficient and might exclude important information as they are usually synthetic and generated, while private-source or real-world datasets are inaccessible to most researchers, except for those who cooperate with financial institutions or industries. In addition, financial institutions are less likely to collaborate to build a more robust detection system due to data privacy regulations, like GDPR. For example, A bank in country A cannot simply share its customers’ transaction records with a partner bank in country B, even if the goal is to protect those same customers from cross-border fraud. Without sufficient and accurate data, ML algorithms are hindered from leveraging their full potential to learn the historical behaviors from vast amounts of data, thus leading to poor performance.

Model replicability and concept drift are challenges for financial fraud detection. Most studies only involve one dataset, and while a model obtains promising results on a specific dataset does not guarantee it performs well on other datasets. Moreover, many studies ignore concept drift, which happens a lot in time series data, and exclude the time attribute while training. This will probably cause negative effects on the models’ performance.

Data resampling is one of the techniques to address data imbalance problems, faced by all studies and methods in the field of financial fraud detection, as fraudulent transactions are usually much fewer than legitimate transactions. Although data resampling techniques help improve models’ performances, they, especially the traditional ways like undersampling and oversampling, also increase the risk of introducing bias, potential loss of valuable information, and the creation of noisy or inaccurate synthetic samples that can lead to overfitting.

Intensive computing resources required are a disadvantage for DL and Hybrid, which usually involve more complex structures, requiring more training and processing time. However, real-time detection systems always allow little response time to approve or reject a transaction. For instance, when a customer makes an online purchase, the fraud detection system must analyze the transaction, check historical patterns, and decide whether to block or approve it—often within a few hundred milliseconds. During that brief window, high latency causes system inefficiency and leads to customer complaints.

5.2. Future Scopes

Involving financial metrics and addressing more of the financial impact are pressing issues anticipated in future studies to mitigate this financial risk. Instead of relying on traditional ML model evaluation metrics like accuracy, future research can prioritize CS (

Hajek et al., 2023) or CRR (

Kim et al., 2019) to estimate the model’s performance financially, aligning with operational risk management. Moreover, the trade-off between FPR and True Positive Rate (TPR) is encouraged to be considered (

Zhang et al., 2021).

Incorporating IML strategies to explain models, features, and results in future studies of financial fraud detection is imperative. IML methods, including SHAP, feature permutations, feature occlusion, PDP, and LIME (

Allen et al., 2024), are good ways to address the interpretability of “Black Box Model” and understand the models’ decisions. Moreover, it helps detect unfair bias. For example, auditors can use IML techniques to check whether a model’s decisions are overly influenced by sensitive attributes like age or location.

Integrating novel technologies like GNNs, metaheuristics, time series forecasting models, blockchain, and FL to emphasize different sides of financial fraud detection could be considered. GNNs and metaheuristic algorithms could be used for feature representation and hyperparameter optimization to enhance performance, while time series forecasting models could be included to solve concept drift. Blockchain, known for its distributed ledger and secured blocks, together with FL, can enhance the performance of ML in real-time financial transaction fraud detection without sharing sensitive information between financial institutions. This combination could effectively mitigate the data privacy constraints that prevent banks from sharing sensitive information with each other. Moreover, FL framework allows organizations across sectors like financial institutions and telecommunication companies, etc. working together to integrate multimodal data, such as financial transaction data (tabular), customers’ portraits (image), message contents (text), phone call contents (audio), etc., developing more robust and resilient detection system, and complying with regulations, like GDPR simultaneously.

Various advanced feature engineering and hyperparameter tuning strategies are expected to enhance model performance. More preprocessing strategies could be focused on in future studies of financial fraud detection. For example, our findings suggest that methods like the statistical HOBA framework and complex neural networks, such as Autoencoder (AE), demonstrate superior power for model improvement. Future work could leverage such approaches, including statistical feature selection that aggregates fraud-related components and advanced neural networks for effective feature representation.

6. Conclusions

This research exhaustively analyzes 41 recent papers on ML for detecting transaction fraud—a key financial operational risk. It provides a comprehensive review of their advantages and disadvantages. Traditional ML methods like Logistic Regression (LR) and Random Forest (RF) demonstrate strong classification performance on small, randomly undersampled transaction fraud datasets. However, they may show instability when classifying new data points. DL approaches, particularly Transformer models and Continuous-Coupled Neural Networks (CCNNs)—which were originally designed for unstructured data—have shown superior power on transactional tabular data. However, DL suffers from difficulties such as poor interpretability and intensive computational demands. Ensemble and Hybrid methods, which strategically combine multiple ML techniques, tend to deliver more robust performance in fraud detection. Nonetheless, they face limitations, such as issues with generalizability, interpretability, or high resource consumption, depending on the specific base algorithms used. A comparison across the taxonomy indicates that Ensemble methods demonstrate superior average performance over the other three categories. Data balancing generally improves model performance, while inappropriate feature engineering can negatively impact results. Employing financial metrics, applying feature explanation techniques, considering temporal patterns, and addressing financial data privacy are all crucial for assessing financial significance in external fraud prevention. These elements are also key to aligning with risk management frameworks, such as the Basel operational risk standards (

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, 2024), and regulations like GDPR and Scam Prevention Framework (

The Treasury, 2024).

Future work in this domain could employ more preprocessing alternatives, focus on metrics such as the False Positive Rate (FPR), True Positive Rate (TPR), and other financial metrics like Cost Reduction Rate (CRR), Cost Savings (CS), to evaluate model performance and financial impact, and implement Interpretable ML (IML) strategies to explain the results. Advanced technologies like Federated Learning (FL), which allows collaborations across multiple organizations, could be considered to mitigate data privacy concerns. The use of the Hybrid Method, which integrates multiple ML techniques for tasks such as data balancing, feature engineering, hyperparameter optimization, and classification to enhance model performance, and the Ensemble Method, which leverages the diversity of the various ML models to yield a more robust result, might be a trend for future-generation financial fraud detection systems.