Bank Leverage Restrictions in General Equilibrium: Solving for Sectoral Value Functions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Model

2.1. Households

2.2. Banks

2.3. Aggregation

2.4. Adding an Exogenous Leverage Constraint to the Model

2.4.1. Household Marginal Utility in Bankers’ Value Function

2.4.2. Decomposing Bank’s Value Function

2.4.3. Bank Steady State Value Function and the Leverage Cap

2.5. Equation for the Household’s Lifetime Expected Utility

2.5.1. Household’s Lifetime Expected Utility

2.5.2. Households’ Utility Function

3. Evaluating Leverage Restrictions

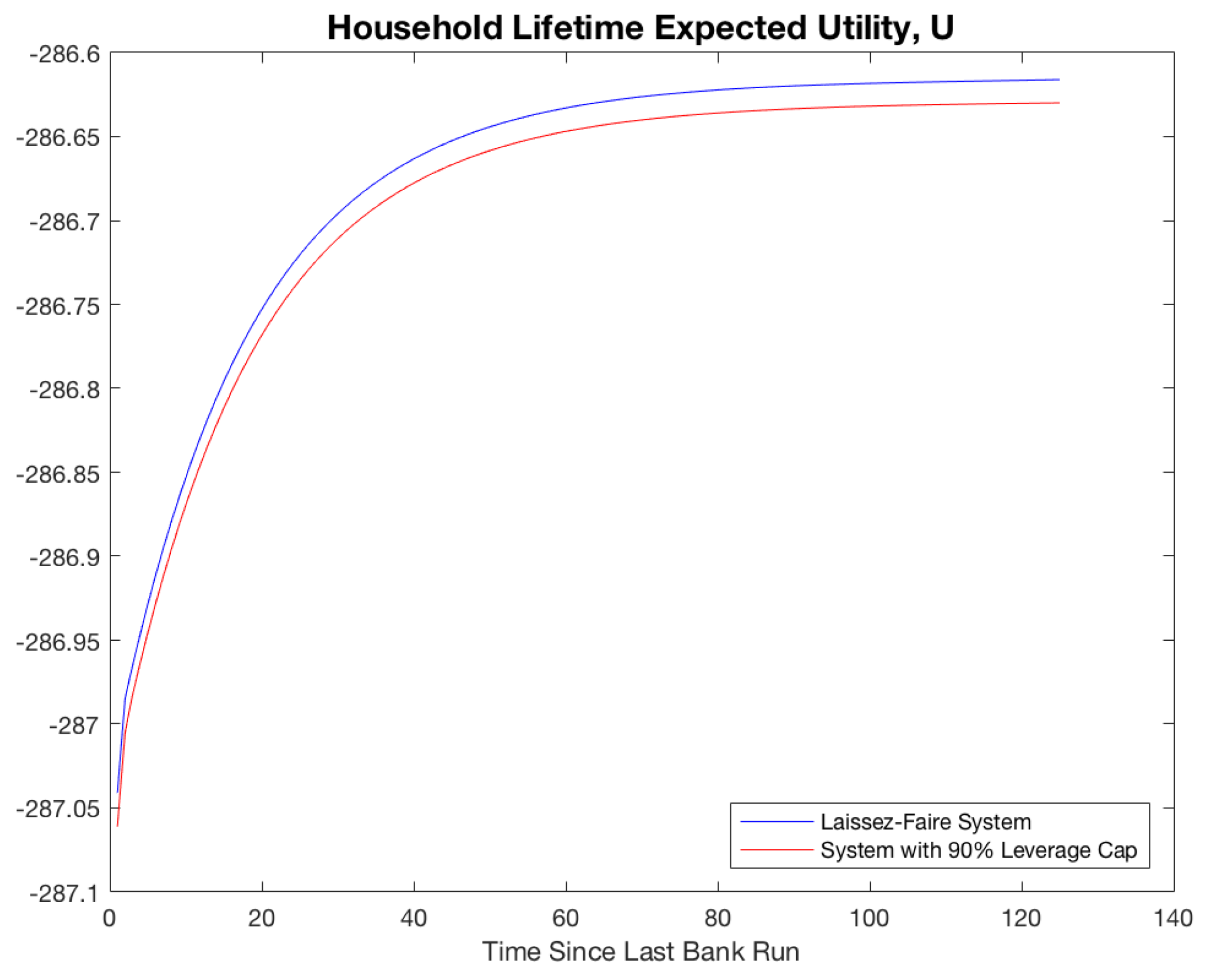

3.1. Welfare Implications of Leverage Restrictions

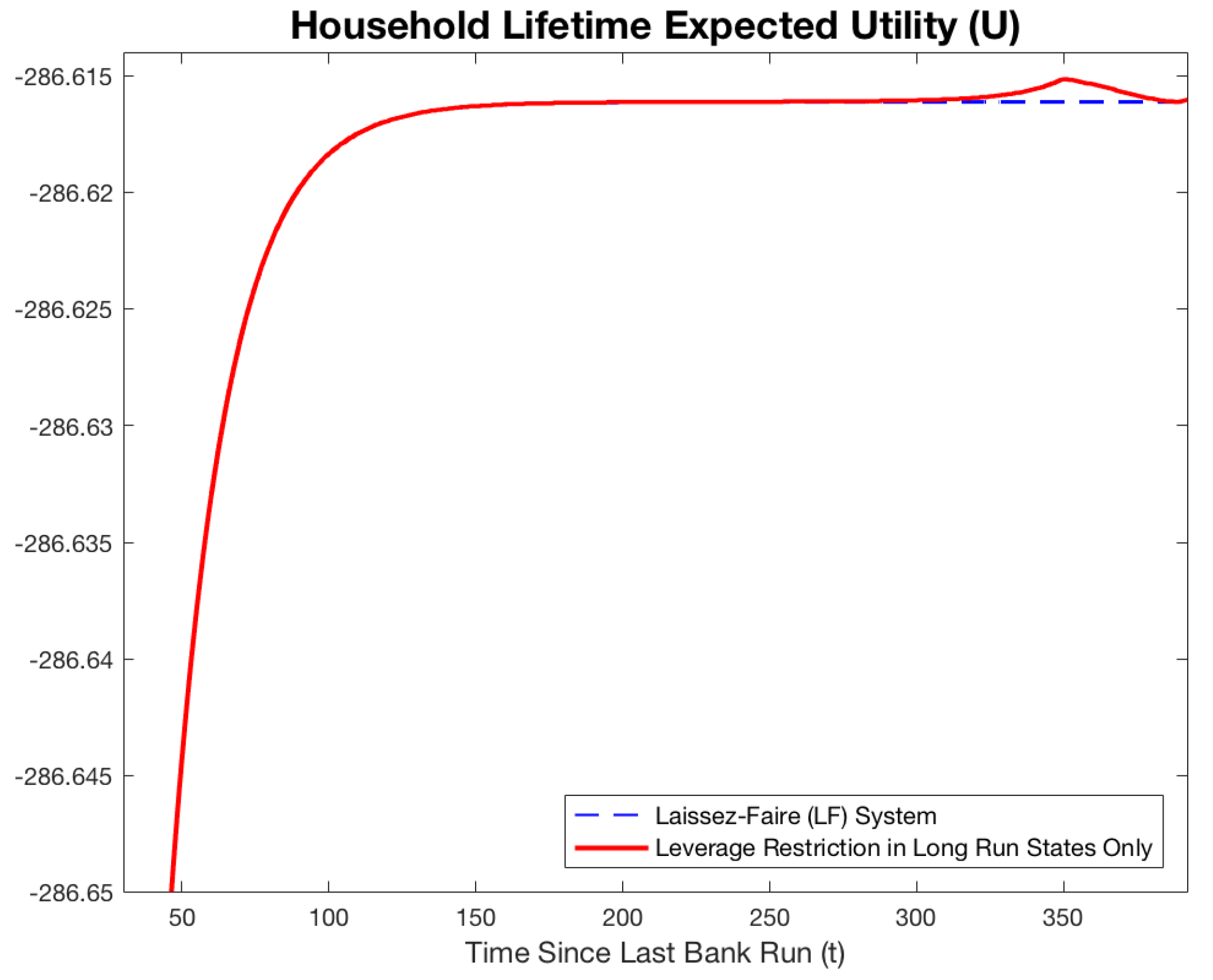

3.2. System Dynamics Under Multi-Period Leverage Restriction

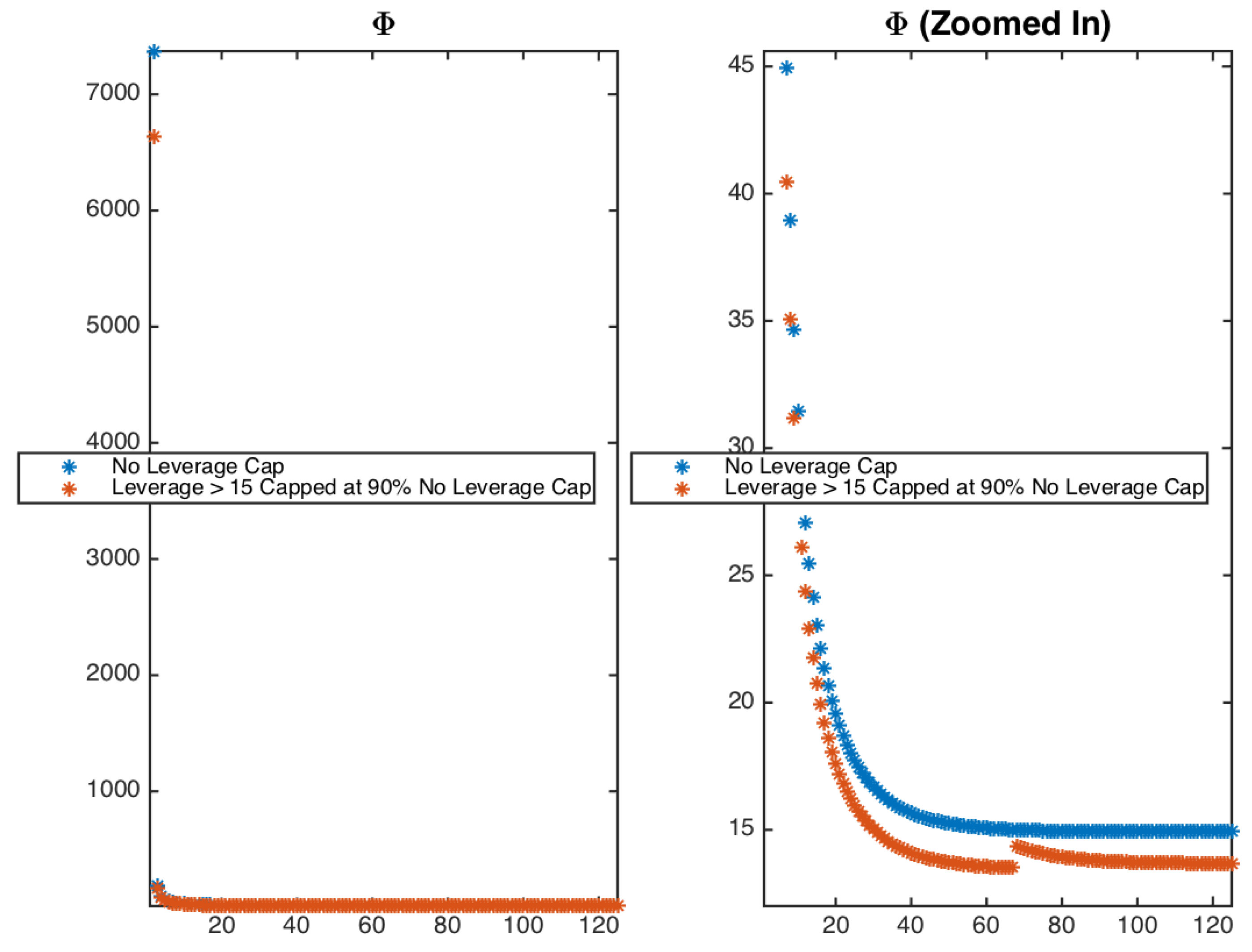

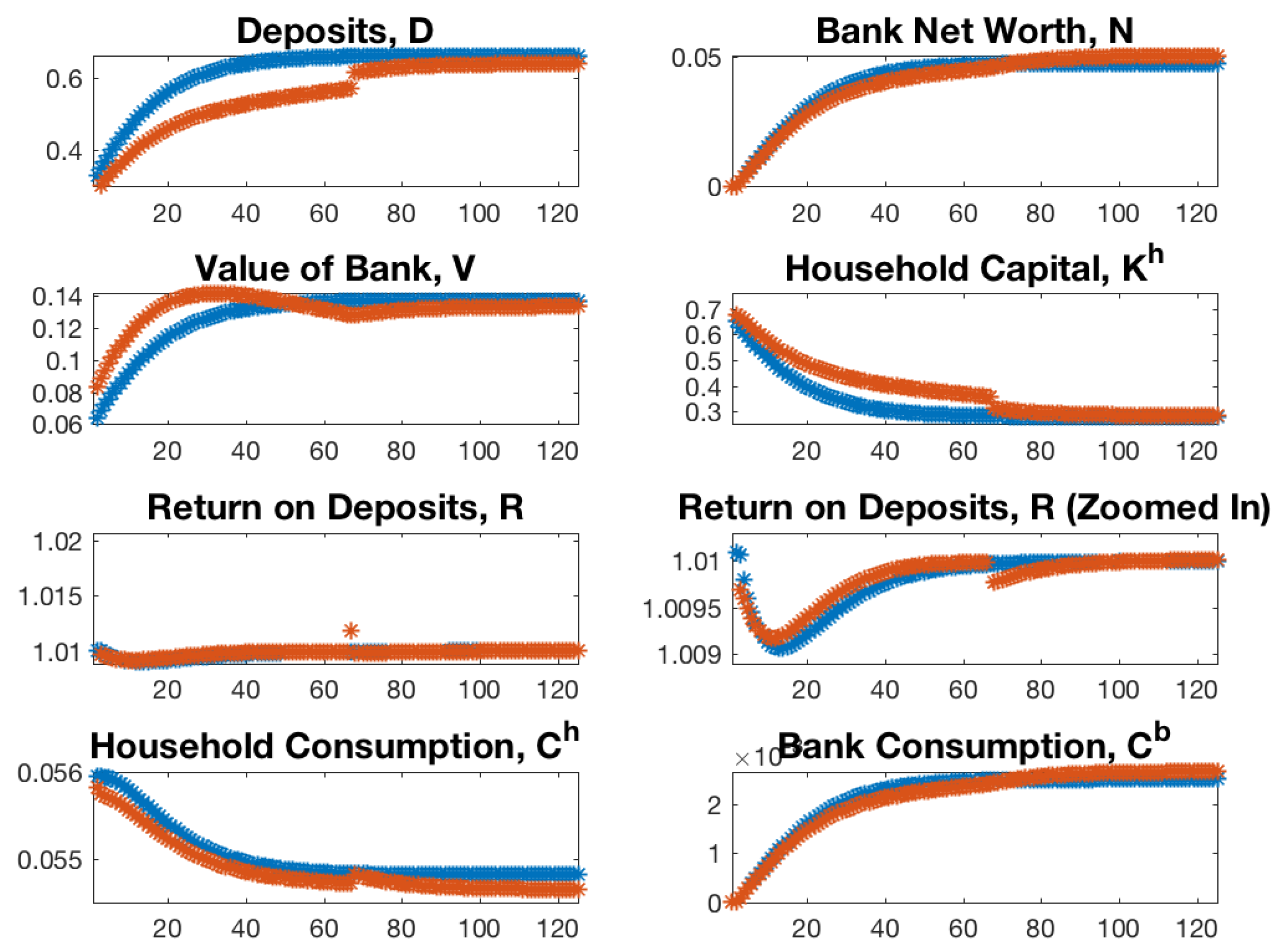

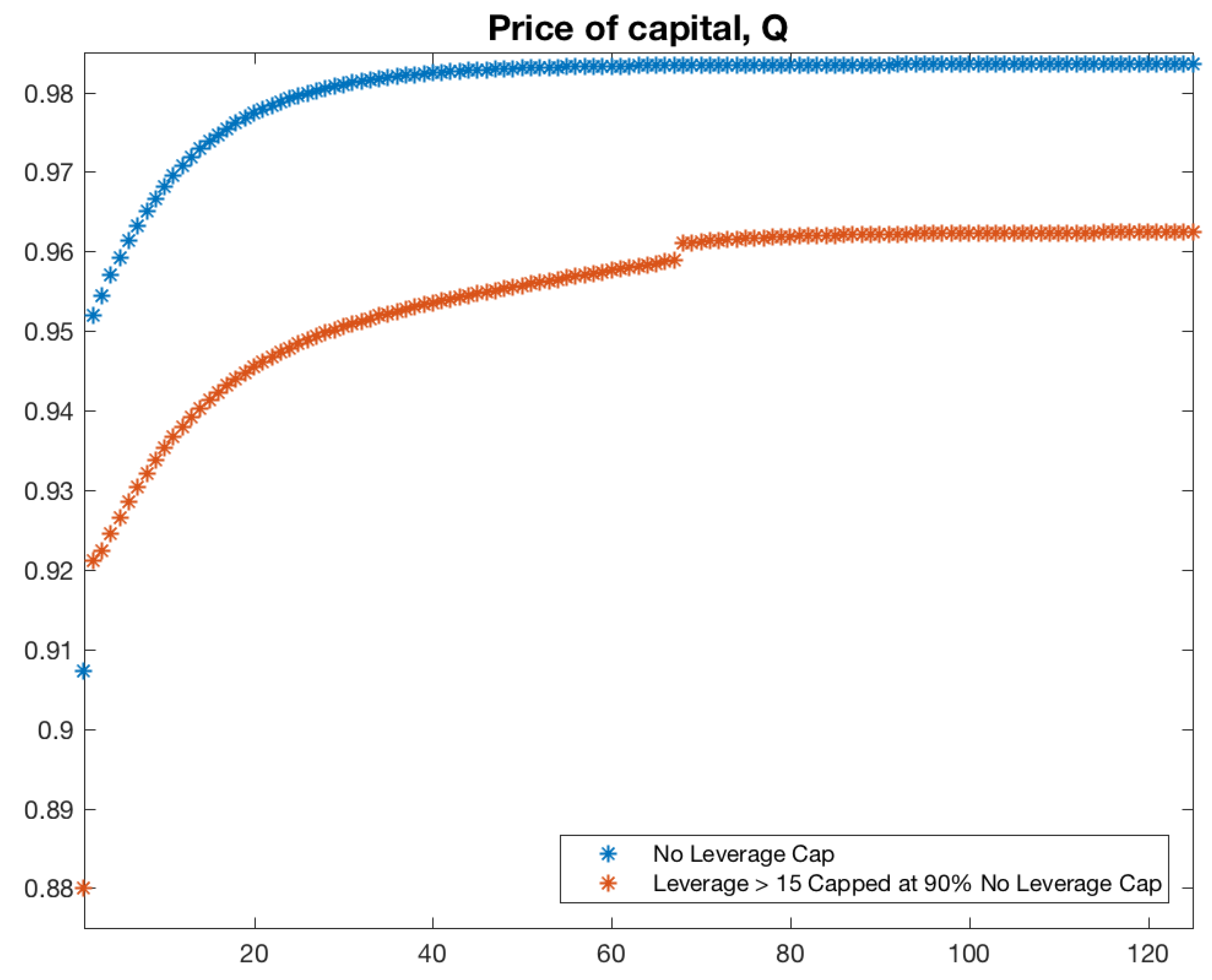

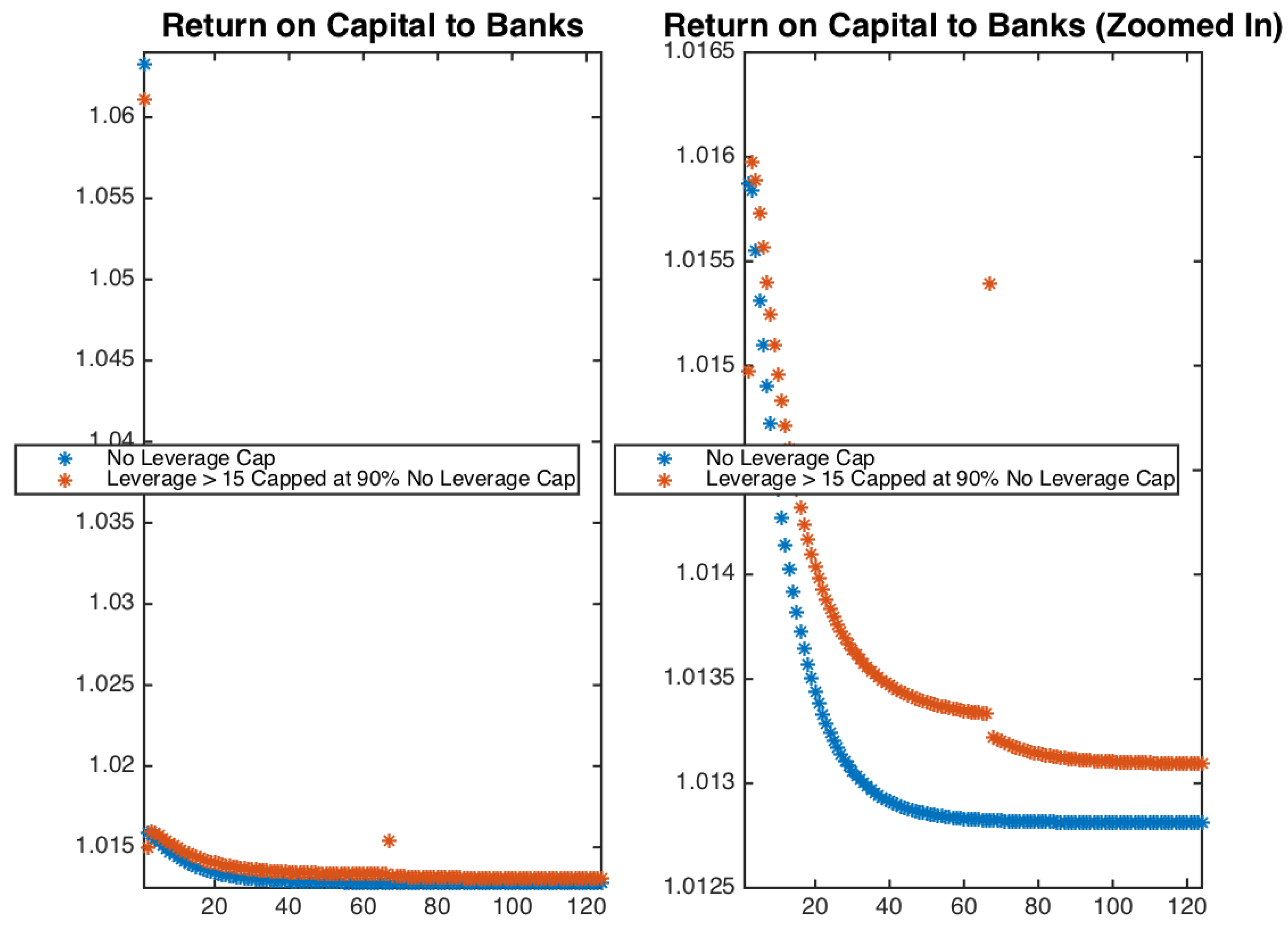

3.2.1. Effect of Multi-Period Leverage Restriction on Economic Variables

3.2.2. Implications for Economic Stability

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Press Release, Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, Group of Governors and Heads of Supervision announces higher global minimum capital standards (12 September 2010), http://www.bis.org/press/p100912.pdf accessed on 31 August 2025. |

| 2 | Tapia, Jose Maria, Ruth Leung, and Hashim Hamandi, “Banks’ Supplementary Leverage Ratio”, The OFR Blog, 2 August 2024. Certain off-balance sheet exposures partially responsible for institutions’ failures during the GFC are explicitly included in the SLR. |

| 3 | See, e.g., Evan Weinberger, “Leverage Cap Leaves Big Banks with Unpalatable Choices”, Law360, 9 July 2013. A leverage ratio cap of 5% was proposed for the eight GSIBs insured bank holding companies, with additional surcharges to be phased in. “Fed and FDIC agree 6% leverage ratio for US Sifis”, Central Banking Newsdesk, 10 July 2013. “US Banking Regulators Propose Changes to the Enhanced Supplementary Leverage Ratio for US GSIBs”, Skadden, 8 July 2025. |

| 4 | Hamdi et al. (2023) shows that Basel III decreased bank mortgage originations and pushed banking activity toward nonbanks and Acharya (2012) argues that Basel III is fundamentally flawed but has redeeming features when combined with the Dodd Frank Act. |

| 5 | The evidence in Lewis and Padi (2025a, 2025b) suggests that micro-level frictions in credit markets (pooled pricing and servicing incentives) interact with macroprudential constraints. |

| 6 | Just prior to the Great Recession, commercial banks operated with leverage ratios near 8 and interest margins of roughly 200 basis points (e.g., Philippon, 2015). In the shadow banking system, leverage multiples ranged from very modest levels (2 or below) for hedge funds to extremely high levels for investment banks (20 to 30). However, Singh and Aitken (2010) show that repo collateral reuse increased dealer-bank leverage by 50% more than these standard estimates during 2007–2009. Interest margins ranged from 25 basis points for ABX securities to 100 or more for agency mortgage-backed securities and BAA corporate bonds. |

References

- Acharya, V. V. (2012). The dodd-frank act and basel iii: Intentions, unintended consequences, and lessons for emerging markets (ADBI Working Paper, Tech. Rep.). ADBI. [Google Scholar]

- Acharya, V. V., Gale, D., & Yorulmazer, T. (2011). Rollover risk and market freezes. The Journal of Finance, 66(4), 1177–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arfaoui, J., & Uhlig, H. (2025). Maturity risks and bank runs (Tech. Rep.). National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Begenau, J. (2020). Capital requirements, risk choice, and liquidity provision in a business-cycle model. Journal of Financial Economics, 136(2), 355–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernanke, B. S., Gertler, M., & Gilchrist, S. (1999). The financial accelerator in a quantitative business cycle framework. Handbook of Macroeconomics, 1, 1341–1393. [Google Scholar]

- Christiano, L., Dalgic, H., & Li, X. (2022). Modelling the Great Recession as a Bank Panic: Challenges. Economica, 89, S200–S238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiano, L., & Ikeda, D. (2016). Bank leverage and social welfare. American Economic Review, 106(5), 560–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, H. L., & Kehoe, T. J. (2000). Self-fulfilling debt crises. The Review of Economic Studies, 67(1), 91–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Nicolò, G., Gamba, A., & Lucchetta, M. (2014). Microprudential regulation in a dynamic model of banking. The Review of Financial Studies, 27(7), 2097–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, D. W., & Dybvig, P. H. (1983). Bank runs, deposit insurance, and liquidity. Journal of Political Economy, 91(3), 401–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennis, H. M., & Keister, T. (2010). Banking panics and policy responses. Journal of Monetary Economics, 57(4), 404–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gertler, M., & Kiyotaki, N. (2015). Banking, liquidity, and bank runs in an infinite horizon economy. American Economic Review, 105(7), 2011–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gertler, M., Kiyotaki, N., & Prestipino, A. (2020). Credit booms, financial crises, and macroprudential policy. Review of Economic Dynamics, 37, S8–S33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, I., & Pauzner, A. (2005). Demand–deposit contracts and the probability of bank runs. The Journal of Finance, 60(3), 1293–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorton, G., & Metrick, A. (2012). Securitized banking and the run on repo. Journal of Financial Economics, 104(3), 425–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorton, G., & Ordonez, G. (2020). Good booms, bad booms. Journal of the European Economic Association, 18(2), 618–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdi, N., Jiang, E. X., Lewis, B. A., Padi, M., & Pal, A. (2023). The rise of nonbanks in servicing household debt. Olin business school center for finance & accounting research paper 2023/08. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4550175 (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- He, Z., & Krishnamurthy, A. (2012). A model of capital and crises. The Review of Economic Studies, 79(2), 735–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiyotaki, N., & Moore, J. (1997). Credit cycles. Journal of Political Economy, 105(2), 211–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, B. A. (2021). The impact of collateral value on mortgage originations. Olin business school center for finance & accounting research paper no. 2023/04. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4423818 (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Lewis, B. A. (2023). Creditor rights, collateral reuse, and credit supply. Journal of Financial Economics, 149(3), 451–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, B. A., & Padi, M. (2025a). Regulating secondary loan markets: Evidence from small business lending. Olin business school center for finance & accounting research paper (2025/01). Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract_id=5187744 (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Lewis, B. A., & Padi, M. (2025b). The cost of servicing debt pools. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5386507 (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Martinez-Miera, D., & Suarez, J. (2014). Banks’ endogenous systemic risk taking. Manuscript, CEMFI, 42. Available online: https://martinezmiera.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/mmiera-suarez2014.pdf (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Morris, S., & Shin, H. S. (1998). Unique equilibrium in a model of self-fulfilling currency attacks. American Economic Review, 88, 587–597. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T. T. (2015). Bank capital requirements: A quantitative analysis. Charles A. Dice center working paper 2015-14. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2356043 (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Philippon, T. (2015). Has the US finance industry become less efficient? On the theory and measurement of financial intermediation. American Economic Review, 105(4), 1408–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, M. J. (2010). The derivatives market’s payment priorities as financial crisis accelerator. Stanford Law Review, 63, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Singh, M. M., & Aitken, J. (2010). The (sizable) role of rehypothecation in the shadow banking system (No. 10-172). International Monetary Fund.[Green Version]

- Van den Heuvel, S. J. (2008). The welfare cost of bank capital requirements. Journal of Monetary Economics, 55(2), 298–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Average Number of Periods | No Leverage Cap | Leverage Cap |

|---|---|---|

| Between Bank Runs | 81.3 | 109.9 |

| To Reach SS | 318.1 | 273.9 |

| In SS (Conditional on Reaching) | 87.1 | 82.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lewis, B.A. Bank Leverage Restrictions in General Equilibrium: Solving for Sectoral Value Functions. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 519. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18090519

Lewis BA. Bank Leverage Restrictions in General Equilibrium: Solving for Sectoral Value Functions. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(9):519. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18090519

Chicago/Turabian StyleLewis, Brittany Almquist. 2025. "Bank Leverage Restrictions in General Equilibrium: Solving for Sectoral Value Functions" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 9: 519. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18090519

APA StyleLewis, B. A. (2025). Bank Leverage Restrictions in General Equilibrium: Solving for Sectoral Value Functions. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(9), 519. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18090519