The Role of Campaign Descriptions and Visual Features in Crowdfunding Success: Evidence from Africa

Abstract

1. Introduction

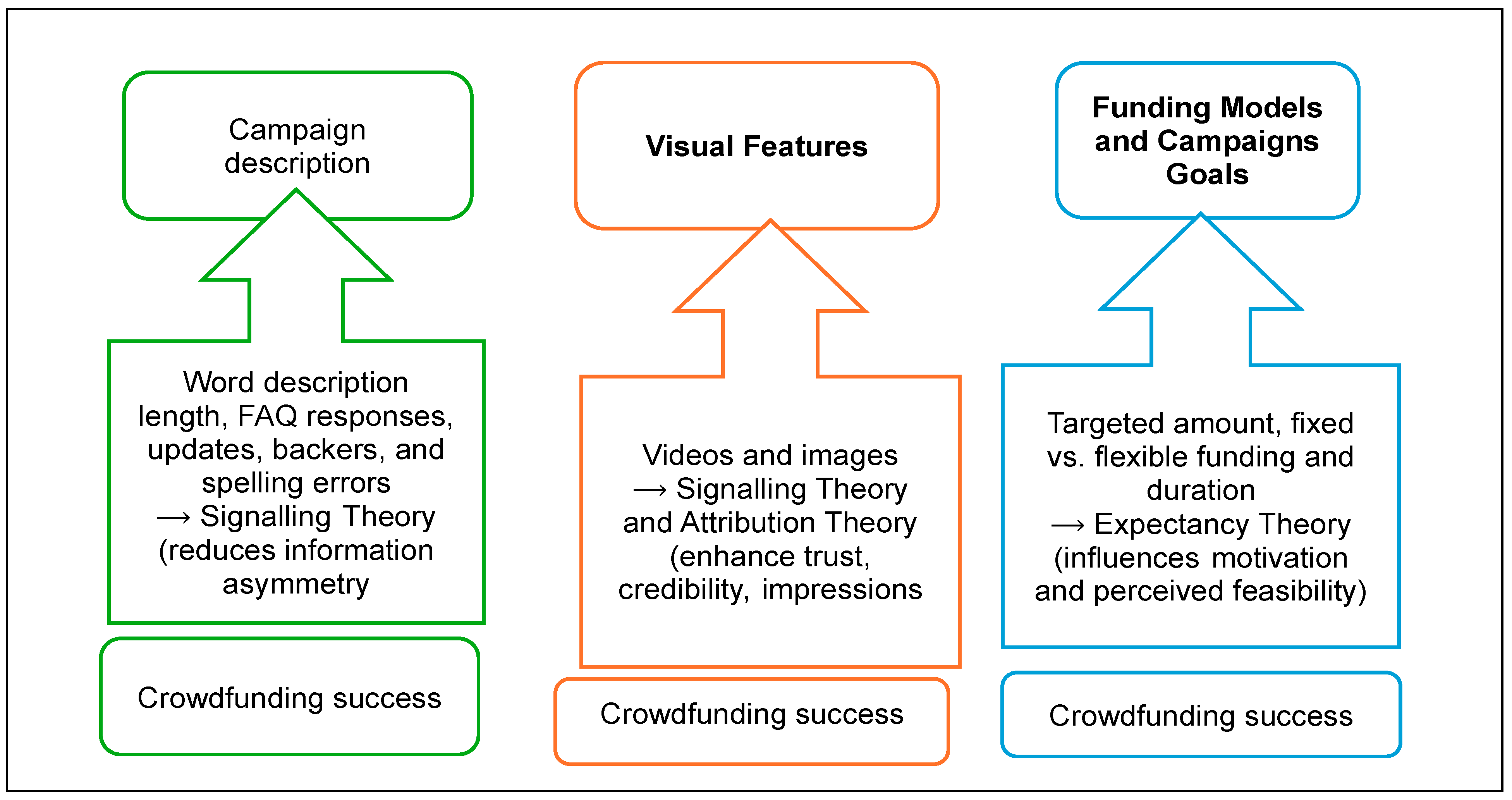

- Examine the role of campaign language and tone of narrative (e.g., word, length, and emotional intensity) on crowdfunding success and thus explain the way textual accounts are used as quality project signals.

- Evaluate the impact of visual content (e.g., video and image content) on the chances of campaign success, in terms of how visual cues build confidence and credibility on crowdfunding platforms.

- Describe how text and image signals combine to construct backers’ perceptions and decisions, utilising signalling theory to frame a theoretical explanation of their efficacy.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Campaign Description Features

2.2. Visual Features

2.3. Structural and Funding Features

2.4. Backer Engagement and Campaign Dynamics

2.5. Conceptual Model

3. Research Methods and Materials

3.1. Dataset Description

3.2. Estimation Models

- The dependent variable in question is determined by the percentage of the funding goal that has been met. The project is deemed successful if the rate is 100% or higher. The project is classified as unsuccessful if it is less than 100%. Alternatively, the dependent variable can be defined as success, measured by a binary indicator where 1 signifies a successful project, and 0 indicates an unsuccessful one.

- Dependent variable: The dependent variable is defined as success, evaluated using a binary system where 1 indicates a successful project, and 0 signifies an unsuccessful one.

- The independent variables are word description length, spelling errors, images, flexible funding, videos, and duration. Table 1 below explains all the variables.

4. Findings and Discussion of the Results

- OLS regression results

- Logistic regression results

5. Conclusions

5.1. Management Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Theoretical Implications

- It extends signalling theory (Spence, 1973) into the African context, showing that not all signals (e.g., spelling or FAQs) are equally valued across cultural or institutional settings. Instead, visual and quantitative signals (images, backers, and achievable targets) carry more weight.

- The negative effect of flexible funding challenges the assumption (common in Western studies) that flexibility attracts more participation (Steigenberger, 2017). In Africa, rigidity may be interpreted as commitment, reinforcing the credibility of the entrepreneur.

- The study uses multiple campaign-related variables simultaneously through OLS and logistic regression, and the study empirically demonstrates that determinants of success ratio and binary success can differ, adding nuance to crowdfunding performance measurement.

5.4. Empirical Implications

5.5. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adamska-Mieruszewska, J., Zientara, P., Mrzygłód, U., & Fornalska, A. (2024). Identifying factors affecting intention to support pro-environmental crowdfunding campaigns: Mediating and moderating effects. Journal of Alternative Finance, 1(1), 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamska-Mieruszewska, J., Zientara, P., Mrzygłód, U., & Fornalska, A. (2025). Motivations for participation in green crowdfunding: Evidence from the UK. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 27(3), 6139–6164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjakou, O. J. L. (2021). Crowdfunding: Genesis and comprehensive review of its State in Africa. Open Journal of Business and Management, 9(2), 557–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlers, G. K. C., Cumming, D., Günther, C., & Schweizer, D. (2015). Signalling in equity crowdfunding. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(4), 955–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, T. H., Davis, B. C., Webb, J. W., & Short, J. C. (2017). Persuasion in crowdfunding: An elaboration likelihood model of crowdfunding performance. Journal of Business Venturing, 32(6), 707–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anglin, A. H., & Pidduck, R. J. (2022). Choose your words carefully: Taking advantage of crowdfunding’s language for success. Business Horizons, 65(1), 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awotunde, J. B., Adeniyi, E. A., Ogundokun, R. O., & Ayo, F. E. (2021). Application of big data with fintech in financial services. In Fintech with artificial intelligence, big data, and blockchain (pp. 107–132). Springer. Available online: http://www.springer.com/series/16276 (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Babayoff, O., & Shehory, O. (2022). The role of semantics in the success of crowdfunding projects. PLoS ONE, 17(2), e0263891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, G., Geng, B., & Liu, L. (2019). On fixed and flexible funding mechanisms in reward-based crowdfunding. European Journal of Operational Research, 279(1), 168–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, S. J., Noseworthy, T. J., Pancer, E., & Poole, M. (2022). Extracting image characteristics to predict crowdfunding success. arXiv, arXiv:2203.4172-41894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, Q. N., & Bui, S. (2022). Understanding the success of sharing economy startups: A necessary condition analysis. In Proceedings of the 55th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS) (pp. 1–9). University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa/IEEE Computer Society Press. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/download/86772484/0438.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Camilleri, M. A., & Bresciani, S. (2024). Crowdfunding small businesses and startups: A systematic review, an appraisal of theoretical insights and future research directions. European Journal of Innovation Management, 27(7), 2183–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascino, S., Correia, M., & Tamayo, A. (2019). Does consumer protection enhance disclosure credibility in reward crowdfunding? Journal of Accounting Research, 57(5), 1247–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C. S. R., Parhankangas, A., Sahaym, A., & Oo, P. (2020). Bellwether and the herd? Unpacking the u-shaped relationship between prior funding and subsequent contributions in reward-based crowdfunding. Journal of Business Venturing, 35(2), 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, H. F., Moy, N., Schaffner, M., & Torgler, B. (2021). The effects of money saliency and sustainability orientation on reward-based crowdfunding success. Journal of Business Research, 125, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, D., Hornuf, L., Karami, M., & Schweizer, D. (2023). Disentangling crowdfunding from fraud funding. Journal of Business Ethics, 182, 1103–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, W. E., & Giovannetti, E. (2018). Signalling experience and reciprocity to temper asymmetric information in crowdfunding evidence from 10,000 projects. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 133, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, S., Duff, B. R. L., & Karahalios, K. (2023). It is all about criticism: Understanding the effect of social media discourse on legal crowdfunding campaigns. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 7(CSCW1), 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikaputra, R., Sulung, L. A. K., & Kot, S. (2019). Analysis of success factors of reward-based crowdfunding campaigns using multi-theory approach in ASEAN-5 countries. Social Sciences, 8(10), 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos Felipe, I. J., Mendes-Da-Silva, W., Leal, C. C., & Santos, D. B. (2022). Reward crowdfunding campaigns: Time-to-success analysis. Journal of Business Research, 138, 214–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doud, J. I. (2017, December). Multicollinearity and regression analysis. In Journal of physics: Conference series (Vol. 949, No. 1, p. 012009). IOP Publishing. Available online: https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1742-6596/949/1/012009/meta (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Efrat, K., Gilboa, S., & Sherman, A. (2020). The role of supporter engagement in enhancing crowdfunding success. Baltic Journal of Management, 15(2), 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gujarati, D. N., & Porter, D. C. (2009). Basic econometrics (5th ed.). McGraw-Hill/Irwin. Available online: https://books.google.co.kr/books/about/Basic_Econometrics.html?id=6l1CPgAACAAJ&redir_esc=y (accessed on 17 August 2025).

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heider, F. (1958). Perceiving the other person. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2004-21806-002 (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Herd, K. B., Mallapragada, G., & Narayan, V. (2022). Do backer affiliations help or hurt crowdfunding success? Journal of Marketing, 86(5), 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hootsuite. (2020). Social media trends 2020. Available online: https://hootsuite.com/pages/social-media-trends-2020-report (accessed on 19 June 2025). Available online.

- Hou, R., Li, L., Liu, B., & Xin, B. (2020). Returns on investment behaviours on explicit and implicit factors in reward-based crowdfunding based on ELM theory. PLoS ONE, 15(8), e0236979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jáki, E., Csepy, G., & Kovács, N. (2022). Conceptual framework for crowdfunding success factors: Review of the academic literature. Acta Oeconomica, 72(3), 393–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H., Wang, Z., Yang, L., Shen, J., & Hahn, J. (2021). How rewarding are your rewards? A value-based view of crowdfunding rewards and crowdfunding performance. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 45(3), 562–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y., Ding, C., Duan, Y., & Cheng, H. K. (2020). Click to success? The temporal effects of Facebook likes on crowdfunding. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 21(5), 1191–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalnins, A., & Praitis Hill, K. (2025). The VIF score. What is it good for? Absolutely nothing. Organizational Research Methods, 28(1), 58–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, J.-A., & Siering, M. (2019). The recipe of successful crowdfunding campaigns: An analysis of crowdfunding success factors and their interrelations. Electronic Markets, 29(4), 661–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagazio, C., & Querci, F. (2018). Exploring the multi-sided nature of crowdfunding campaign success. Journal of Business Research, 90, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasschuijt, M. (2019). Communication style in online crowdfunding [Bachelor’s thesis, University of Twente]. Available online: http://essay.utwente.nl/78393/ (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Lee, C. H., & Chiravuri, A. (2019). Dealing with initial success versus failure in the crowdfunding market: Serial crowdfunding, changing strategies, and funding performance. Internet Research, 29(5), 1190–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S., Shafqat, W., & Kim, H.-C. (2022). Backers should be aware of the characteristics and detection of fraudulent crowd-funding campaigns. Sensors, 22(19), 7677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G., & Wang, J. (2019). Threshold effects on backer motivations in reward-based crowdfunding. Journal of Management Information Systems, 36(2), 546–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H., & Cao, E. (2023). Competitive crowdfunding under asymmetric quality information. Annals of Operations Research, 329(1), 657–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X., & Hu, X. (2018). Empirical study of the effects of information description on crowdfunding success—The perspective of information communication. Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/iceb2018?utm_source=aisel.aisnet.org%2Ficeb2018%2F76&utm_medium=PDF&utm_campaign=PDFCoverPages (accessed on 24 August 2025).

- Liang, X., Hu, X., & Jiang, J. (2020). Research on the effects of information description on crowdfunding success within a sustainable economy, the perspective of information communication. Sustainability, 12(2), 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T., Gong, X., Liu, Z., & Ma, C. (2021). Direct and configurational paths of capital signals to technology crowdfunding fundraising. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 70(9), 3062–3077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Zhang, K., Xue, W., & Zhou, Z. (2024). Crowdfunding innovative but risky new ventures: The importance of less ambiguous tone. Financial Innovation, 10(1), 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (1990). Work motivation and satisfaction: Light at the end of the tunnel. Psychological Science, 1(4), 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louviere, J. J., Hensher, D. A., & Swait, J. D. (2000). Stated choice methods: Analysis and applications. Cambridge University Press. Available online: https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=nk8bpTjutPQC&oi=fnd&pg=PR9&dq=Louviere+et+al.,+2000&ots=WCWidjbotd&sig=LtE6hgJf3w5J96KkyOlcRFhqJto (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Lu, B., Xu, T., & Fan, W. (2024). How do emotions affect giving? Examining the effects of textual and facial emotions in charitable crowdfunding. Financial Innovation, 10(1), 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z. (2023). Early backers’ social and geographic influences on the success of crowdfunding. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 17(4), 510–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z., & Palacios, S. (2021). Image-mining: Exploring the impact of video content on the success of crowdfunding. Journal of Marketing Analytics, 9(4), 265–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamaro, L. P., & Sibindi, A. B. (2022). Financial sustainability of African small to medium companies during the COVID-19 pandemic: Determinants of crowdfunding success. Sustainability, 14(23), 15865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamaro, L. P., & Sibindi, A. B. (2023). The drivers of successful crowdfunding projects in Africa during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 16(7), 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Gómez, C., Jiménez-Jiménez, F., & Alba-Fernández, M. V. (2020). Determinants of overfunding in equity crowdfunding: An empirical study in the UK and Spain. Sustainability, 12(23), 10054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbarek, S., & Trabelsi, D. (2020). Crowdfunding without Crowd-fooling: Prevention is better than cure. In Corporate fraud exposed: A comprehensive and holistic approach (pp. 221–238). Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollick, E. (2018). Crowdfunding as a font of entrepreneurship: Outcomes of reward-based crowdfunding. In The economics of crowdfunding: Startups, portals and investor behavior (pp. 133–150). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, M., & Badrinarayanan, V. (2021). The effects of brand prominence and narrative characteristics on crowdfunding success for entrepreneurial aftermarket enterprises. Journal of Business Research, 124, 286–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moy, N., Chan, H. F., & Torgler, B. (2018). How much is too much? The effects of information quantity on crowdfunding performance. PLoS ONE, 13(3), e0192012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’brien, R. M. (2007). A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Quality & Quantity, 41(5), 673–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X., & Dong, L. (2023). What determines the success of charitable crowdfunding campaigns? Evidence from China during the COVID-19 pandemic. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 34(6), 1284–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L., Cui, G., Bao, Z., & Liu, S. (2022). Speaking the same language: The power of words in crowdfunding success and failure. Marketing Letters, 33(2), 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, B., Machado, S., Andrews, J., & Kourtellis, N. (2022, June 26–29). I call BS: Fraud detection in crowdfunding campaigns. 14th ACM Web Science Conference 2022 (pp. 1–11), Barcelona, Spain. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petty, R. E., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1986). Communication and persuasion: Central and peripheral routes to change of attitude. Springer. Available online: https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=nFFDBAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA1976&dq=46.%09Petty,+R.+E.+and+Cacioppo,+J.+T.+1986.+Communication+and+persuasion:+Central+and+peripheral+routes+to+change+of+attitude.+New+York:+Springer-Verlag.&ots=igF7zuEIne&sig=yAruYIvh4jvsr4RgZaUjs4NjqSQ (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Pinkow, F. (2023). Determinants of overfunding in reward-based crowdfunding. Electronic Commerce Research, 25(1), 155–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Predkiewicz, K., & Kalinowska-Beszczyńska, O. (2021). Financing eco-projects: Analysis of factors influencing the success of crowdfunding campaigns. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 27(2), 547–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regner, T., & Crosetto, P. (2021). Experience matters. Participation-related rewards increase the chances of success of crowdfunding campaigns. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 30(8), 843–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shneor, R., & Vik, A. A. (2020). Crowdfunding success: A systematic literature review 2010–2017. Baltic Journal of Management, 15(2), 149–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shneor, R., Zhao, L., & Flåten, B.-T. (2020). Advances in crowdfunding: Research and practice. Springer Nature. Available online: https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/41282 (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- Singh, D. P. D., & Poonawala, S. (2021). Crowdfunding: Wordplay to make money. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3932900 (accessed on 16 August 2025).

- Singh, P. D. (2021). Emotional crowdfunding blurbs lead to success (of the campaign, at least). SSRN 3943467. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3943467 (accessed on 16 August 2025).

- Song, Y., Berger, R., Yosipof, A., & Barnes, B. R. (2019). Mining and investigating the factors influencing crowdfunding success. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 148, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, M. (1973). Job market signalling. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 87(3), 355–374. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780122148507500255 (accessed on 28 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Statista. (2024). Crowdfunding—Statistics & facts. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/946668/global-crowdfunding-volume-worldwide-by-type/ (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Steigenberger, N. (2017). Why supporters contribute to reward-based crowdfunding. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 23(2), 336–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St John, J., St John, K., & Han, B. (2022). Motivations of entrepreneurs to back crowdfunding: A latent Dirichlet allocation approach. European Journal of Innovation Management, 25(6), 223–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šarić, M. Š. (2021). Determinants of crowdfunding success in Central and Eastern European countries. Management Journal of Cotemporary Management Issues, 26(2), 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, B. (1985). Attribution theory. In Human Motivation (pp. 275–326). Springer. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-4612-5092-0_7 (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Wessel, M., Adam, M., & Benlian, A. (2019). The impact of sold-out early birds on option selection in reward-based crowdfunding. Decision Support Systems, 117, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y., & Ni, J. (2022). Entrepreneurial learning and disincentives in crowdfunding markets. Management Science, 68(9), 6819–6864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J., Li, Y., Calic, G., & Shevchenko, A. (2020). How multimedia shape crowdfunding outcomes: The overshadowing effect of images and videos on text in campaign information. Journal of Business Research, 117, 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, J.-Y., & Chen, C.-H. (2022). A machine learning approach to predict the success of crowdfunding fintech project. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 35(6), 1678–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, T.-L., Chen, T.-Y., & Lee, C.-C. (2019). Investigate the funding success factors that affect reward-based crowdfunding projects. Innovation, 21(3), 466–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M., Tong, L., Liu, J., Liu, W., & Fan, W. P. (2023). How does fundraiser-claimed product innovation influence crowdfunding outcomes? Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10125/103093 (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Zhang, X., Huang, H., & Xiao, S. (2023a). Behind the scenes: The role of writing guideline design in the online charitable crowdfunding market. Information & Management, 60(7), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Tao, X., Ji, B., Wang, R., & Sörensen, S. (2023b). The success of cancer crowdfunding campaigns: Project and text analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 25, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, M., Lu, B., Fan, W., & Wang, G. A. (2018). Project description and crowdfunding success: An exploratory study. Information Systems Frontiers, 20(2), 259–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zihagh, F., Moradi, M., & Badrinarayanan, V. (2024). A brand prominence perspective on crowdfunding success for aftermarket offerings: The role of textual and visual brand elements. Journal Of Product & Brand Management, 33(1), 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zribi, S. (2022). Effects of social influence on crowdfunding performance: Implications of the COVID-19 pandemic. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 9(1), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dependent Variables | Measurements |

|---|---|

| Completion ratio (CR) | Ratio of the amount raised over the amount of money requested |

| Success (SC) | The binary variable of 1 if the targeted amount was obtained and 0 otherwise |

| Independent variables | |

| Description length (DL) | Total number of words written on the crowdfunding campaign (transformed into a log) |

| Spelling errors (SPR) | A dummy variable of 1 if the spelling error is available on the campaign and 0 otherwise |

| Image (IM) | A dummy variable of 1 if the image is available on the website and 0 otherwise |

| Flexible funding (FXF) | A dummy variable of 1 if the crowdfunding campaign is flexible and 0 if it is a fixed funding model |

| Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) | The number of frequently asked questions on the crowdfunding platform (transformed as a log) |

| Targeted amount (TA) | A binary variable of 1 if the target amount is achieved and 0 otherwise |

| Backers (BCK) | The number of supporters who contributed to the project (transformed into a log) |

| Duration (DRN) | The number of days for a campaign to raise funds (transformed into a log) |

| Variables | Observation | Mean | Standard Deviation | Minimum | Maximum | Median | Kurtosis | Skewness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Completion ratio | 850 | 0.161 | 0.735 | 0.000 | 14.585 | 0.000 | 215.66 | 12.588 |

| Description length | 850 | 572.19 | 550.18 | 0.000 | 5779.000 | 446.50 | 16.0082 | 2.5246 |

| Spelling errors | 850 | 0.282 | 0.4504 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 1.93510 | 0.9670 |

| Image | 850 | 0.6858 | 0.4644 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.64149 | −0.8009 |

| Flexible funding | 850 | 0.7612 | 0.4266 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 2.50094 | −1.2251 |

| Targeted amount | 850 | 4.0735 | 0.8037 | 1.699 | 7.477 | 4.000 | 3.67432 | 0.5179 |

| Frequently asked questions | 850 | 0.1000 | 0.9135 | 0.000 | 13.000 | 0.000 | 120.091 | 10.533 |

| Backers | 850 | 19.662 | 118.54 | 0.000 | 2438.00 | 0.000 | 234.548 | 13.604 |

| Duration | 850 | 44.530 | 17.242 | 2.000 | 67.000 | 46.00 | 1.94235 | −0.4966 |

| Success | 850 | 0.0835 | 0.2768 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 10.0629 | 3.0104 |

| CR | DL | SPR | IM | FXF | TA | FAQ | BCK | DRN | SC | VIF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR | 1.000 | DP | |||||||||

| DL | 0.2252 *** | 1.000 | 1.231 | ||||||||

| SPR | −0.0283 | 0.13148 *** | 1.000 | 1.045 | |||||||

| IM | 0.099 *** | 0.302 *** | 0.1035 *** | 1.000 | 1.115 | ||||||

| FXF | −0.2098 *** | −0.184 *** | 0.0934 * | −0.1056 *** | 1.000 | 1.140 | |||||

| TA | −0.107 *** | 0.153 *** | −0.0097 | 0.0507 | 0.080** | 1.000 | 1.131 | ||||

| FAQ | 0.151 *** | 0.158 *** | −0.0258 | 0.074 ** | −0.1955 *** | 0.0195 | 1.000 | 1.083 | |||

| BCK | 0.422 *** | 0.205 *** | −0.0467 | 0.026590 | −0.1475 *** | 0.0583 * | 0.195 *** | 1.000 | 1.102 | ||

| DRN | −0.1027 ** | 0.002148 | 0.02072 | 0.041281 | 0.201 *** | 0.29 *** | −0.0496 | −0.113 *** | 1.000 | 1.15 | |

| SC | 0.6053 *** | 0.208 *** | −0.057 * | 0.122 *** | −0.2896 *** | −0.123 *** | 0.246 *** | 0.444 *** | −0.162 *** | 1.000 | DP |

| Hypothesis Variables | OLS Regression (Completion Ratio) | Logistic Regression (Success) |

|---|---|---|

| H1: Description length (DL) | 0.001 *** (0.04) | 0.0005 (0.0004) |

| H2: Spelling errors (SPR) | −0.046 (0.051) | −0.772 (0.051) |

| H3: Image (IM) | 0.0811 (0.051) | 0.5957 (0.001) |

| H4: Flexible funding (FXF) | −0.173 *** (0.056) | −1.012 ** (0.462) |

| H5: Targeted amount (TA) | −0.134 *** (0.0293) | −2.841 *** (0.5159) |

| H6: Frequently asked questions (FAQs) | 0.0272 (0.025) | 0.0839 (0.188) |

| H7: Backers (BCK) | 0.0023 *** (0.001) | 0.0760 *** (0.009) |

| H8: Duration (DRN) | 0.0001 (0.001) | 0.0010 (0.0013) |

| C | 0.6228 *** (0.126) | 5.8782 *** (0.077) |

| Pseudo (McFadden) | 0.6723 | |

| 0.23862 | ||

| DW test | 2.03 | |

| Number of observations | 849 | 849 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mamaro, L.P.; Sibindi, A.B.; Makina, D. The Role of Campaign Descriptions and Visual Features in Crowdfunding Success: Evidence from Africa. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 518. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18090518

Mamaro LP, Sibindi AB, Makina D. The Role of Campaign Descriptions and Visual Features in Crowdfunding Success: Evidence from Africa. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(9):518. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18090518

Chicago/Turabian StyleMamaro, Lenny Phulong, Athenia Bongani Sibindi, and Daniel Makina. 2025. "The Role of Campaign Descriptions and Visual Features in Crowdfunding Success: Evidence from Africa" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 9: 518. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18090518

APA StyleMamaro, L. P., Sibindi, A. B., & Makina, D. (2025). The Role of Campaign Descriptions and Visual Features in Crowdfunding Success: Evidence from Africa. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(9), 518. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18090518