Abstract

Access to business financing in Europe has historically been a challenge for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which represent a significant share of economic activity and employment in Europe. This issue has been significantly intensified since the global financial crisis, disproportionately affecting this segment. This study analyzes firm-level determinants influencing access to alternative financing sources, including crowdfunding, venture capital, and other non-bank channels, using data from the 2023 SAFE covering 15,855 firms across Europe. Results indicate that firm size significantly affects access, with larger, established firms more likely to secure such funding. However, younger, innovation-driven firms demonstrate a higher propensity to pursue equity and crowdfunding options, driven by their need for flexible and early-stage capital. Sectoral patterns also emerge: industrial firms more often obtain public grants, while service-sector firms lead in adopting equity-based and crowdfunding models. The findings highlight the critical role of innovation capacity and international orientation in broadening financial access. Digital platforms are identified as key enablers in democratizing funding, particularly for SMEs. This research advances understanding of SME financing dynamics within evolving financial landscapes and provides actionable insights for policymakers and practitioners aiming to promote inclusive and sustainable access to finance.

1. Introduction

Over the past decade, access to business financing in Europe has been progressively restricted, a trend that has become particularly pronounced in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. This development has resulted in a contraction of bank lending (Popov & Udell, 2012), historically the principal channel of external finance for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Representing 99.8% of all businesses in the European Union, SMEs are a cornerstone of the productive fabric and heavily reliant on bank credit to sustain growth, foster innovation, and maintain competitiveness (Roman & Rusu, 2015; Guercio, 2021). The credit crunch has severely constrained their access to financial resources, triggering a ripple effect that compromises not only firm-level development but also the aggregate productivity of national economies (Ferrando & Mulier, 2015).

The consequences of this financial contraction extend beyond liquidity shortages; they have reshaped the strategic orientation of many European firms, particularly those in vulnerable economies. The crisis also exposed structural weaknesses and systemic vulnerabilities in the European financial architecture, particularly in peripheral eurozone economies such as Italy, Spain, Ireland, Portugal, and Greece. In these contexts, eroding trust in banking institutions deepened economic tensions and further impeded firms’ ability to secure financing (Cavalluzzo et al., 2002). These developments underscored the urgent need to diversify financing channels and promote alternative instruments that complement traditional banking and mitigate systemic risk (Martínez et al., 2022).

In recognition of these challenges, European institutions have promoted various initiatives aimed at reducing structural dependency on bank financing and expanding access to diversified financial instruments. The European Commission’s Green Paper on the long-term financing of the European economy (2013) identified the importance of dismantling barriers that limit SME access to alternative financing, including crowdfunding and venture capital (European Commission, 2013). In parallel, the Small Business Act emphasized access to finance as the second most pressing challenge for European SMEs, advocating for an integrated policy response that would enhance connectivity between enterprises and capital markets.

Alternative financing, as defined by Gulati and Higgins (2003) and Baum and Silverman (2004), comprises those instruments that operate outside traditional banking circuits and formal equity markets. These include innovative mechanisms such as crowdfunding, venture capital, peer-to-peer lending, and microfinance. These instruments not only offer greater flexibility but also often adapt more rapidly to the evolving financial needs of businesses. According to Li and Zahra (2012) and Cho and Lee (2018), alternative finance provides a complementary pathway for firms encountering limitations within conventional financial channels, and is especially valuable in addressing credit market imperfections that disproportionately affect SMEs.

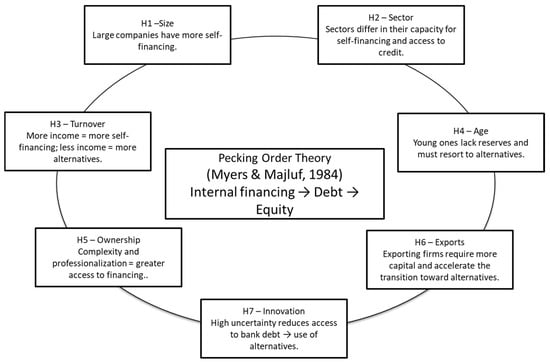

The liquidity crisis also prompted a significant behavioral transformation within the business sector, encouraging firms to seek unconventional financial tools to maintain operations and strategic objectives. In this context, the pecking order theory, formulated by Myers and Majluf (1984), provides a fundamental framework for understanding firms’ financing behavior. The theory posits that firms follow a hierarchical approach to raising capital: they first rely on internal resources, such as retained earnings; then on debt; and finally, as a last resort, on external equity. This hierarchy primarily reflects information asymmetries and the costs associated with issuing new financial instruments. As a result, managers tend to favor internal financing, which mitigates the risk of adverse market signals and avoids diluting owners’ equity. Nevertheless, in today’s environment, where internal funds and debt may be insufficient, alternative financing mechanisms—such as crowdfunding, venture capital, and peer-to-peer lending—serve as vital complementary sources, helping firms bridge gaps left by traditional channels. This shift in financing priorities highlights the growing relevance of alternative mechanisms, which firms increasingly turn to when traditional sources prove inadequate.

In this regard, alternative financing has emerged as a relevant and increasingly institutionalized set of options in response to the exhaustion of traditional channels (Bruton et al., 2015; Sendra-Pons et al., 2023). Nevertheless, several barriers hinder its full integration into the financial ecosystem. Among them, information asymmetry is particularly relevant. Van Auken (2005) notes that limited knowledge of such instruments often results in inefficient capital structures and suboptimal financial decision-making. These findings point to the need for more effective dissemination mechanisms and the development of a transparent environment that fosters trust between investors and entrepreneurs.

The role of knowledge and education in this process is fundamental. The degree of familiarity that entrepreneurs have with alternative financial instruments plays a pivotal role in shaping their financial strategies. As Seghers et al. (2012) emphasize, enhanced awareness of these tools can reduce asymmetries and foster more effective and evidence-based financial behavior. This underscores the need for public and private initiatives that promote financial education, capacity building, and accessible information as essential levers to support wider adoption of alternative mechanisms.

In this sense, the development of a more diversified and inclusive financial ecosystem is not merely a response to past crises, but a strategic necessity in the face of an increasingly complex and dynamic economic landscape. The combination of traditional and alternative instruments can contribute to economic resilience and ensure that firms are better prepared to respond to structural and cyclical shocks. Although the penetration of alternative finance remains relatively incipient in the European context, its growth trajectory presents significant opportunities to reduce dependency on banks and support sustainable long-term financing for the productive sector.

Against this backdrop, the present study aims to analyze the business-related factors influencing access to alternative sources of financing. These include variables such as firm size and age, industry sector, degree of internationalization (measured by export intensity), turnover, ownership structure, and level of innovation. In addition, the study explores whether different financing alternatives exhibit homogeneous or heterogeneous behaviors depending on these firm characteristics, offering a more nuanced understanding of how organizational traits condition access to finance.

Since 2016, the literature on alternative financing mechanisms for SMEs has experienced remarkable growth, as evidenced by numerous publications (Laso et al., 2024). However, despite the expansion of these alternatives—including crowdfunding and peer-to-peer lending—a significant empirical gap persists (Bruton et al., 2015; Kersten et al., 2017). While theoretical debates are abundant, few studies have rigorously examined the actual effects of alternative financing on firm performance and SMEs’ access to capital (Mochkabadi & Volkmann, 2020; Sharma et al., 2024; Verma et al., 2023).

This limitation is reflected in the scarcity of comprehensive analyses assessing the effectiveness and broader implications of these models (Ha et al., 2025; Offiong et al., 2024; Sanga & Aziakpono, 2023). Previous research has primarily focused on regulatory or technological aspects (Tello-Gamara et al., 2022), often overlooking the practical impact of alternative financing on SMEs.

In this context, the present study addresses this gap by providing a detailed analysis of the concrete effects of alternative financing on SMEs’ financing capacity. The study’s relevance and timeliness are underscored by its dual contribution: theoretically, by enriching the conceptual understanding of alternative finance; and practically, by informing public policies and business strategies aimed at broadening access to financial resources. Thus, this research contributes not only to academic knowledge but also to policy innovation and entrepreneurial decision-making in an era that demands more flexible, inclusive, and resilient financial frameworks.

To address these objectives, the article is structured as follows: Section 2 presents the theoretical framework underpinning the study. Section 3 outlines the research methodology. Section 4 reports the empirical findings, and Section 5 offers a discussion of these results in relation to the existing literature. Finally, Section 6 concludes with a synthesis of key insights and the theoretical and practical contributions of the study.

2. Theoretical Framework

This section delves into firms’ access to alternative financing sources, a phenomenon of increasing relevance, particularly within a globalized context marked by offshoring and continuous technological advancements. Numerous studies have identified a set of key variables that directly influence firms’ capacity to obtain finance. These include intrinsic firm characteristics, the profiles of both lenders and borrowers, prevailing financial market conditions, collateral requirements, and persistent information asymmetry (Hernández-Cánovas & Martínez-Solano, 2010). Martínez et al. (2022) broaden this perspective, noting that factors such as firm size, age, ownership structure, sector of activity, innovation level, managerial gender diversity, and the broader macroeconomic and legal context significantly impact financial accessibility. Furthermore, a firm’s financial stability and historical performance are recognized as critical determinants for securing external funding (Holton et al., 2013; McQuinn, 2019). Within this framework, the present study will focus on analyzing firm-level characteristics as explanatory factors for access to alternative finance (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Influence of firm-specific variables. Source: Own elaboration (Myers & Majluf, 1984).

2.1. Firm Size

Firm size, commonly measured by the number of employees, stands as a pivotal factor in accessing alternative finance. Microenterprises (1–9 employees) and small businesses (10–49 employees) inherently face greater challenges in securing sufficient funding due to persistent information asymmetries that limit credit supply from traditional channels (Berger & Udell, 1998). These firms, often more susceptible to the uncertainty and risk inherent in their early growth stages, tend to rely more heavily on informal financing mechanisms, such as support from family and friends (Allen et al., 2013).

Conversely, larger firms enjoy improved access to finance due to their intrinsic ability to convey greater credibility in financial markets (Ferri & Murro, 2015; Kijkasiwat & Phuensane, 2020). This larger scale not only enhances their bargaining power but also reduces the perceived risk for investors (Cenni et al., 2015). Moreover, firm size is inversely correlated with credit risk, as smaller firms exhibit a higher probability of default (Farinha & Félix, 2015). Empirical evidence from Casey and O’Toole (2014) and Rahman et al. (2017) reinforces this idea, suggesting that larger firms more easily access alternative financing, particularly when conventional credit is restricted.

Building on these arguments, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1:

Larger companies have greater ease in accessing alternative financing sources.

2.2. Sector of Activity

The business sector plays a significant role in determining access to external finance, as capital needs and risk profiles vary considerably among them. Industrial firms, for instance, typically face fewer credit constraints compared to service and retail businesses, primarily due to their higher investment in tangible assets that can serve as collateral (Martínez et al., 2022). However, this characteristic also implies an increased dependence on external finance and a heightened sensitivity to interest rate changes (Hall et al., 2000). Construction firms, meanwhile, encounter additional obstacles related to prolonged payment cycles and liquidity constraints, whereas service-sector firms generally require less capital due to lower fixed asset investments (Harrison et al., 2004).

Firms in sectors perceived as high-risk or with limited internal resources also face funding challenges, which directly impact their capital structure (López-Gracia & Sogorb-Mira, 2008). Similarly, sectors characterized by intense innovative activity experience greater barriers to finance, given the elevated uncertainties, inherent risks, and often delayed returns of such investments (Degryse et al., 2012; Guercio et al., 2016). Although the SAFE survey’s confidentiality protocols preclude the inclusion of sector-specific data for large companies, the existing literature consistently suggests that sector is a differentiating factor in access to financing sources.

Based on this sectoral differentiation, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2:

There are no significant differences in the use of alternative financing depending on the productive sector in which the company operates.

2.3. Turnover

Firms generally prioritize internal financing, such as retained earnings, to reduce their reliance on external debt. Nonetheless, growing firms often increase their debt levels to support expansion and meet escalating capital needs (Degryse et al., 2012). Small, high-growth firms frequently resort to external financing due to insufficient retained earnings to sustain their development (Cassar, 2004). Factors such as profitability, liquidity, and growth expectations are crucial determinants in decisions regarding external finance (Bongini et al., 2019). Small innovative firms, in particular, encounter additional challenges in obtaining external finance due to higher risks and uncertain project outcomes (Block, 2012). Ferrando and Mulier (2015) note that firms with lower income and profits are more likely to experience financial constraints, whereas profitable and growth-oriented firms actively pursue external finance (Cosh et al., 2009). The literature thus suggests that a higher turnover, indicative of stability and cash flow generation capacity, can facilitate access to a broader range of financing options, including alternative ones.

In this regard, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3:

Firms with higher turnover are more likely to access alternative financing sources.

2.4. Firm Age

The firm lifecycle implies that a company’s financial structure evolves as it matures. Over time, firms accumulate tangible assets and financial credibility, which reduces information asymmetries and improves their access to financing under better terms and at lower costs (Berger & Udell, 1998; Gompers, 1995). Financial Lifecycle Theory (Berger & Udell, 1998) posits that financing choices shift with business maturity: young firms often rely on self-financing or informal capital sources due to higher opacity, while mature firms can access formal mechanisms such as venture capital.

Age and size are, in fact, strong indicators of a firm’s viability and creditworthiness (Avery et al., 1998). Younger firms, lacking extensive financial history, are subject to greater credit rationing (Kirschenmann, 2016; Dierkes et al., 2013), which often compels them to explore alternative financing options (Chavis et al., 2011). These firms also tend to exhibit higher default rates, which increases the perceived risk for lenders (Comeig et al., 2015; Farinha & Félix, 2015). Nevertheless, Rahman et al. (2017) found a positive correlation between firm age and access to finance, particularly for microenterprises, as the quality of their financial reporting improves over time.

Thus, we formulate the following hypothesis:

H4:

Younger SMEs with banking limitations are more likely to rely on informal loans or non-bank financing.

2.5. Business Ownership

The profile of decision-makers within a firm significantly influences capital structure decisions (Chittenden et al., 1996; Ferrando & Griesshaber, 2011). While traditional financial theories often assume entrepreneurs possess comprehensive knowledge of all financing alternatives, in practice, many lack adequate understanding, leading to suboptimal choices (Van Auken, 2005). Entrepreneurs tend to favor financing sources that imply minimal control dilution and lower transaction costs (Vanacker & Manigart, 2010).

An entrepreneur’s human and social capital also impacts financing behavior. Greater familiarity with financial instruments enhances decision-making and access to suitable financing alternatives (Seghers et al., 2012). Firms with more complex ownership or corporate structures—characterized by multiple shareholders or formalized governance—are often perceived as more credible and stable, thereby increasing their attractiveness to alternative finance providers. Such structures may signal a higher level of professionalization and transparency, aspects valued by investors operating outside traditional banking channels.

In this context, the hypothesis to be studied is as follows:

H5:

Companies with more complex corporate structures are more likely to use alternative financing sources, as the characteristics of the decision-makers significantly influence the capital structure.

2.6. Internationalization/Exports

Numerous empirical studies analyze the links between export activities and financial constraints, consistently highlighting a negative impact of credit restrictions on exports (Wagner, 2019). Firms with better access to finance are not only more likely to export but also demonstrate greater export capacity and resilience (Huang & Liu, 2017). R. Brancati et al. (2018) suggest a negative relationship between a firm’s leverage and export activity, indicating that excessive debt levels can hinder internationalization efforts. Similarly, Pacheco (2017) and Forte and Moreira (2018) find that SMEs with weaker financial conditions are significantly less inclined to engage in export activities.

In the context of developing economies, exports are a key driver of economic growth, and alternative finance can play a crucial role in alleviating export-related financing barriers. Ren and Gao (2023) argue that the development of digital financing platforms can substantially enhance a firm’s likelihood of exporting by addressing conventional credit limitations. This suggests that firms with a stronger international orientation might actively seek out or be better suited for alternative financing, given their exposure to dynamic markets and specific capital needs for global trade.

Based on these arguments, the proposed hypothesis is as follows:

H6:

Firms with higher export activity are more likely to utilize alternative financing sources.

2.7. Innovation

Innovation is fundamental for a firm’s competitiveness and sustainability, as organizations cannot thrive in a dynamic and competitive market environment without it (Rogers, 2004; Mbizi et al., 2013). A lack of innovation can result in lost market opportunities and reduced profit potential (Shefer & Frenkel, 2005). Access to alternative financing, including crowdfunding and peer-to-peer lending platforms, has transformed the financial sector by offering direct, non-intermediated funding channels (Beyi, 2018; Segal, 2016).

Securing finance is vital for innovation processes; however, innovative firms often face particular challenges in attracting capital due to the higher perceived risks and often delayed returns associated with their projects (Lee et al., 2015; Chittenden et al., 1996). As a result, they may avoid conventional credit channels in favor of alternative options (R. Brancati et al., 2018). The higher risk and uncertainty of innovation activities make traditional financing less accessible, rendering alternative finance an essential resource (McQuinn, 2019). This suggests a natural affinity between highly innovative firms and the more flexible, higher-risk-tolerance nature of alternative financing.

Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H7:

Firms with higher innovation capacity are more likely to access alternative financing sources.

3. Materials and Methods

The empirical analysis in this study is based on data obtained from the Survey on the Access to Finance of Enterprises (SAFE), a large-scale, widely recognized biannual instrument jointly conducted by the European Central Bank (ECB) and the European Commission (EC) since 2009. This survey is designed to collect detailed firm-level information, focusing on the six-month period preceding each wave. This provides dynamic and up-to-date insights into the financial conditions and experiences of enterprises across Europe. SAFE’s continuity and regularity make it an invaluable data source for monitoring trends in the European business financing ecosystem.

The primary objective of this survey is to capture comprehensive information on firms’ structural characteristics—such as their size, sector of activity, age, and turnover—as well as a detailed assessment of their financing needs and experience in accessing external funds. For the current research, data from Wave 29 of the SAFE survey, covering the period from April to September 2023, were utilized. This selection ensures the temporal relevance of the findings and reflects the most recent financial dynamics.

3.1. Sample Composition and Representativeness

The dataset used for this study exclusively includes non-financial private enterprises, explicitly excluding firms from the agricultural and public administration sectors. This sample delimitation was established to ensure homogeneity and consistency in the financial behavior analyzed, allowing for greater comparability among the units of observation.

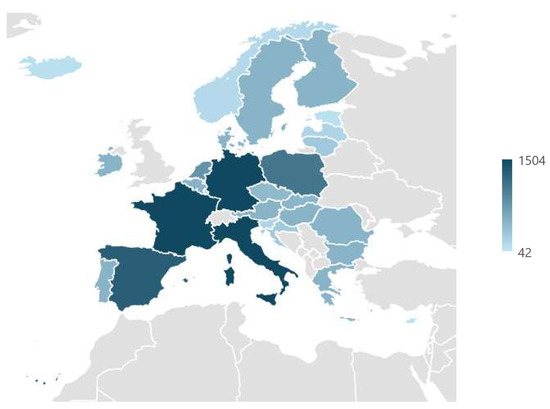

The final sample comprises 15,855 valid observations, originating from both EU and non-EU countries. As illustrated in Figure 2, a deliberate overrepresentation of larger economies was pursued. This sampling design addresses the need to ensure that the sample adequately reflects business dynamics in key national markets. Specifically, the six countries with the highest representation—Italy, Germany, France, Spain, Poland, and the Netherlands—collectively account for 48.5% of the total sample, which aligns with their relative economic weight within the European region.

Figure 2.

Data composition by country. Source: Own elaboration based on SAFE ECB/EC survey data.

This sampling strategy not only enables the identification of cross-country patterns but also facilitates the detection of structural differences in financing behavior. For example, the substantial inclusion of data from Italy and Germany provides robust insights into industrial sector dynamics, while contributions from France and Spain offer valuable knowledge on commerce and service-oriented firms. Poland, as a rapidly growing emerging economy in Eastern Europe, provides crucial input on evolving market behavior, and the Netherlands, with its high integration in international trade and innovation ecosystems, enriches the analysis with its specific characteristics. This diversified sample composition is fundamental for generating robust and generalizable results within the European context.

3.2. Data Nature and Variable Categorization

The SAFE survey is primarily qualitative in nature, implying that most collected variables are categorical. These variables represent discrete groups or classifications, rather than continuous numerical values. The inherent non-parametric nature of categorical data is a crucial aspect for the selection of statistical techniques, as they do not meet the assumptions required for traditional parametric tests (such as normality of distribution or homogeneity of variance). This justifies the need to employ specialized statistical methods appropriate for this type of data.

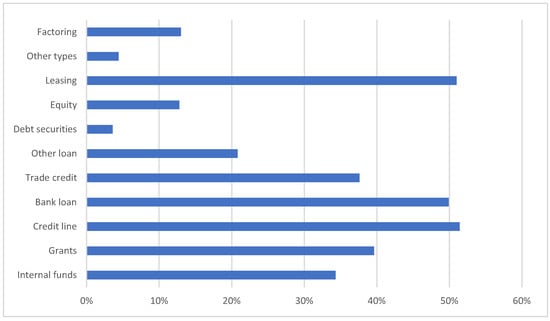

Section 3 of the SAFE questionnaire is specifically dedicated to firm financing. In particular, Question Q4 asks firms to rate the relevance of various sources of external finance—both current and prospective—for their operations. From the eleven distinct financing sources identified in this question, the present study groups them into two main categories: traditional financing and alternative financing (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Sources of corpora finance. Source: Own elaboration based on SAFE ECB/EC survey data.

While traditional financing sources include bank loans, credit lines, and leasing, the central focus of this research is on alternative financing channels, consistent with the stated research objectives. According to the pecking order theory, firms are expected to follow a hierarchical preference when raising capital, prioritizing internal funds, followed by debt, and equity as a last resort. However, the data from our sample reveal a divergence from this theoretical pattern. While retained earnings remain an important component of internal funding, many firms rely primarily on bank loans and credit lines rather than internal resources. Several factors may explain this deviation. First, SMEs often face limited internal funds relative to their growth ambitions, making debt a necessary source of financing. Second, prevailing market conditions and the post-crisis liquidity environment in Europe may reduce the feasibility of relying solely on internal funds. Third, strategic considerations, such as investment timing, asset acquisition needs, and opportunities for innovation, may drive firms to seek external financing earlier than the pecking order would suggest. Leasing arrangements, trade credit, and public grants also play a supporting role, but the overarching pattern points to a pragmatic adaptation to real-world constraints rather than strict adherence to the theoretical hierarchy.

Nevertheless, while internal funds are not the predominant source, equity-based instruments—such as new share issuance or business angel participation—remain secondary, suggesting that external equity is still treated as a last-resort option, consistent with the logic of the pecking order theory.

In contrast, alternative financing instruments—such as non-bank loans, peer-to-peer lending, crowdfunding, and debt securities—although marginal in their overall use, occupy an increasingly relevant position within firms’ capital structures. These mechanisms offer crucial opportunities to diversify funding and reduce dependence on the traditional banking system, being particularly important for firms facing credit constraints or pursuing innovative business models.

The importance of capital structure and the balance between debt and equity is fundamental, especially for startups and SMEs. As Cassar (2004) points out, financing decisions significantly influence firms’ operational sustainability, risk of failure, performance outcomes, and long-term scalability. Previous studies (Burkart & Ellingsen, 2004) have observed that firms facing liquidity constraints initially turn to bank finance but may subsequently supplement it with alternative sources when traditional avenues are exhausted or inaccessible. Our sample confirms that, while the pecking order theory provides a useful framework, in practice, SMEs adapt their financing strategies to the realities of access, size, and sector-specific constraints.

In line with the methodological approach of Casey and O’Toole (2014), this study focuses on the following non-bank financing sources considered alternative:

- Informal loans and non-bank institutional credit;

- Market-based instruments, such as debt securities issued;

- Public grants or subsidized loans;

- Equity capital;

- Other sources of financing, including peer-to-peer platforms and crowdfunding.

3.3. Statistical Analysis Methods

The statistical analysis was conducted using a univariate approach, where each hypothesized determinant was individually tested against the binary outcome variable indicating the usage of alternative financing. Given the categorical nature of the data, Pearson’s chi-squared test was employed as the primary tool for evaluating associations between variables. For 2 × 2 contingency tables or in cases where expected frequencies were small, Fisher’s exact test was utilized to ensure robustness and precision in significance testing. The choice of these tests is justified by their suitability for analyzing relationships between nominal and ordinal variables, which constitute the majority of data in the SAFE survey.

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 27, which facilitates the execution of tests and the obtaining of reliable results. This software is widely recognized in scientific research for its reliability in executing non-parametric statistical tests and yielding robust results. Pearson’s chi-squared test, in particular, allows for the identification of statistically significant relationships between firm characteristics and their financing behavior by comparing observed frequencies with expected frequencies under the null hypothesis, typically evaluated at a 5% significance level (α = 0.05).

This methodological framework is rigorously appropriate for generating detailed insights into financing patterns across a heterogeneous set of firms and national contexts. The findings derived from this approach aim to contribute to a deeper understanding of the determinants shaping firms’ financial behavior in Europe, with significant implications for both future academic research and public policy formulation.

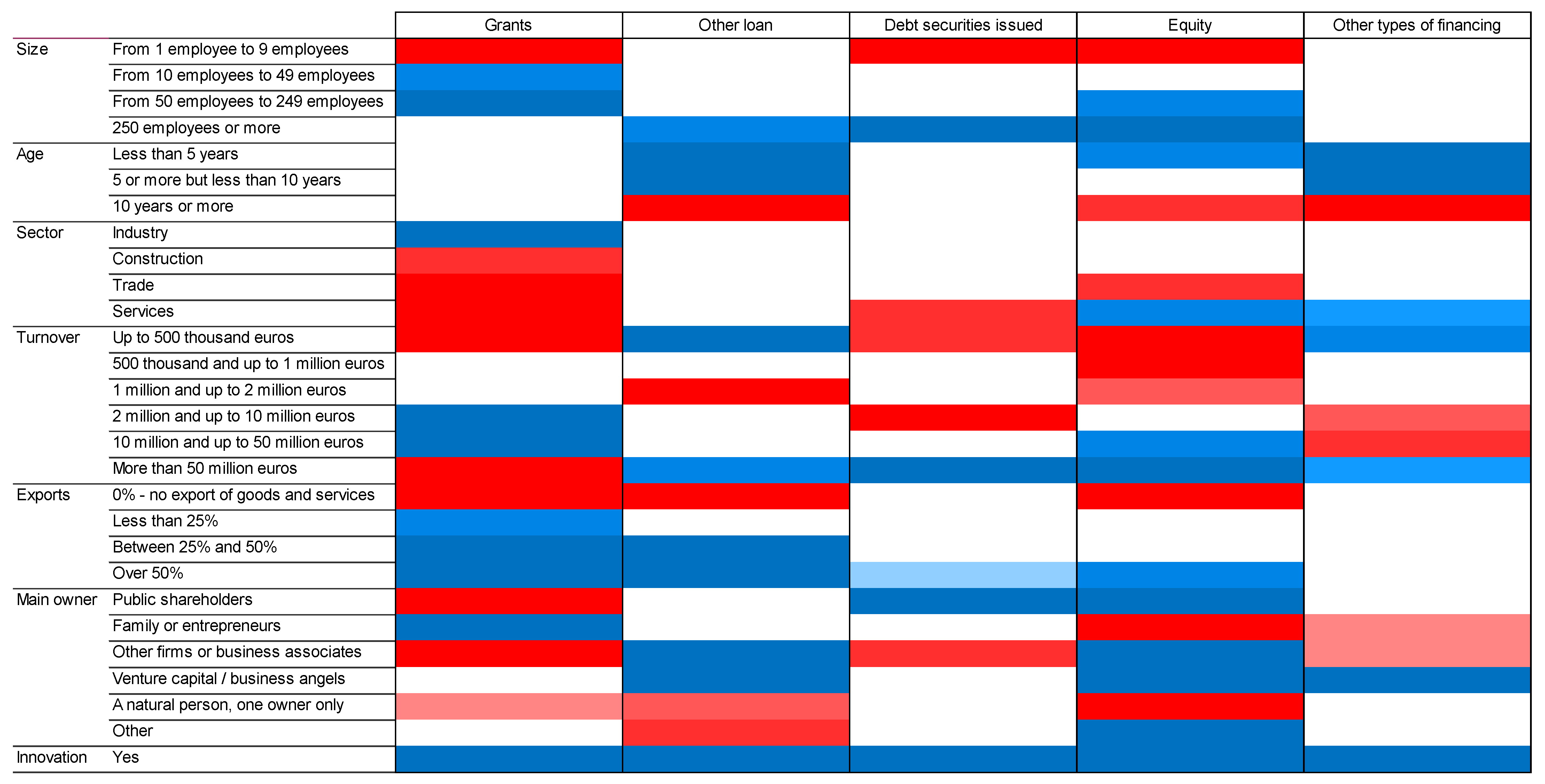

3.4. Heatmaps

To analyze the relationship between business profiles and the probability of success in obtaining different sources of alternative financing, two heat maps were developed.

First, based on two key business variables—firm size and firm age—a two-dimensional matrix was constructed in which each cell represented a specific interval of business characteristics. For each cell, the probability of success in accessing alternative financing was estimated, defined as the proportion of firms that successfully obtained a given source of financing relative to the total number of firms in the same category. The results were visualized through a heatmap in which the color scale reflected the intensity of the estimated probability, where red indicates greater difficulty in achieving success and green represents a higher probability of obtaining that source of financing. This representation allowed for the application of homogeneous color gradations and facilitated the visual interpretation of patterns and clusters.

Second, an additional heatmap was generated based on an independence analysis using the chi-square test between categorical variables representing business characteristics and the different sources of financing. Post hoc comparisons were conducted with a Bonferroni adjustment in order to control for Type I error. In this case, a two-way matrix was constructed in which the rows corresponded to categories of business characteristics and the columns to sources of financing. Each cell was colored according to the level of statistical significance (p-value), applying a progressive color scale. The obtained values were transformed into an intensity scheme, such that color intensity reflected the degree of association between each pair of variables.

This methodological approach enabled the intuitive and visual identification of the most influential business factors in determining access to different sources of alternative financing, thereby providing a graphical tool that enhances the interpretation of results in both academic and business contexts.

4. Results

This section presents the empirical findings derived from the analysis of SAFE survey data, aiming to identify the determinant factors influencing firms’ access to alternative financing sources. Several key explanatory variables were selected: firm size, age, sector of activity, turnover, export activity, ownership structure, and innovation capacity. These variables were chosen based on their potential to affect both the availability of and preference for non-traditional sources of finance, as grounded in the study’s theoretical framework.

4.1. Descriptive Analysis of Alternative Financing Adoption

Table 1 reports the proportion of firms that considered at least one of the five types of alternative financing relevant to their financial structure, disaggregated by organizational characteristics. This breakdown offers critical insight into how structural and operational attributes may shape firms’ financing behavior.

Table 1.

Business characteristics with alternative financing sources.

The working hypotheses for this study posited that an increase in firm size, age, turnover, and export intensity would positively correlate with the likelihood of adopting alternative financing sources. Additionally, significant differences were anticipated in obtaining alternative financing based on sectoral affiliation, innovation intensity, and the firm’s ownership model.

As shown in Table 1, 54.3% of firms indicated that at least one form of alternative financing was relevant to their operations. This suggests a widespread openness among European firms to diversifying their financing strategies beyond conventional banking mechanisms. Notably, the prevalence of alternative financing increases with company size, supporting the initial hypothesis. Only 47.3% of microenterprises (fewer than 10 employees) identified alternative financing as relevant, compared to 61.5% among large enterprises (over 250 employees). This data may reflect greater managerial capacity, financial literacy, and access to information in larger firms, enabling them to explore and utilize a more diverse range of financing options.

In terms of firm age, the results deviate slightly from expectations. Younger firms (up to 5 years old) show relatively high engagement with alternative financing (57.1%), potentially reflecting their greater need for flexible capital structures or limited access to traditional loans. Firms aged 5–10 years report a similar adoption rate (60.7%). Interestingly, firms over 10 years old exhibit the lowest adoption (53.8%), suggesting that more established businesses may rely more heavily on conventional banking, benefiting from longstanding credit relationships and lower perceived risk by lenders.

The sector of activity reveals notable disparities in financing behavior. In line with prior research (Martínez et al., 2022), industrial firms emerge as the most intensive users of alternative financing (62.4%), likely due to their capital-intensive nature and complex investment cycles. Conversely, firms in the trade sector reported the lowest adoption rate (49.3%), possibly due to their more standardized business models, lower capital needs, and stronger reliance on short-term credit lines and trade finance.

With respect to turnover, a clear upward trend is observed: firms with higher annual revenues are significantly more likely to engage in alternative financing. This difference reaches up to 10 percentage points between firms with annual turnover below EUR 0.5 million and those exceeding EUR 50 million. This pattern suggests that firms with greater financial stability and cash flow predictability are more attractive to non-bank investors and are better equipped to navigate the complexities of alternative financial instruments.

Export activity also appears to be a relevant driver. Firms whose exports account for between 25% and 50% of their turnover show the highest likelihood of adopting alternative financing. This is consistent with the need for enhanced working capital and risk mitigation tools when operating across international markets. Such firms may also be more familiar with cross-border financial instruments, enhancing their openness to alternative sources.

Ownership structure exhibits a particularly strong relationship. Firms funded by venture capital exhibit the highest adoption of alternative financing (69.9%), indicating that external equity investors may actively encourage diversified capital structures. In contrast, sole proprietorships are less likely to pursue alternative financing (50.5%), possibly due to a more conservative financial culture, limited administrative capacity, or an aversion to external control.

Finally, innovation emerges as a significant enabler of alternative financing. A total of 61.9% of firms identified as innovative reported using non-traditional financing mechanisms. This relationship likely stems from the higher capital intensity and risk associated with innovation, which may not align well with traditional credit scoring. Innovative firms may thus turn to alternative investors willing to absorb higher uncertainty in exchange for future growth potential. These descriptive findings provide initial support for several hypotheses, highlighting structural and strategic firm attributes as relevant predictors of alternative financing adoption. However, descriptive statistics alone cannot confirm the statistical validity of these relationships. Therefore, inferential tests were conducted to explore the strength and significance of the observed associations.

4.2. Inferential Analysis: Chi-Square Tests

Table 2 presents the results of the chi-squared tests for independence between each organizational variable and the five categories of alternative financing. The reported p-values determine whether the relationships observed in the descriptive analysis are statistically significant, with a significance threshold set at α = 0.05. A p-value below this threshold allows for the rejection of the null hypothesis of independence, suggesting a statistically significant association between the variables.

Table 2.

Relationship between alternative financing and business characteristics.

As anticipated, firm size (measured by the number of employees) shows a strong and highly significant association with nearly all alternative financing types (p < 0.01), with the exception of “other financing.” This confirms that larger firms are systematically more capable of attracting alternative financing, likely due to stronger financial reporting, corporate governance, and perceived lower risk.

The age variable shows significant associations with only two financing types: “other loans” and “capital equity.” These results suggest that while age may not universally drive alternative financing adoption, it does influence access to specific instruments. Notably, equity financing is often targeted at firms with longer operational histories and more robust business models, while “other loans” may fill access gaps for firms that do not qualify for traditional lending.

The sector of activity is significantly associated with grants and equity, pointing to differential access across industries. Industrial firms are more likely to receive public subsidies, possibly due to government support for strategic sectors, while equity investment is prevalent among firms with high scalability, commonly found in technology, manufacturing, or innovation-intensive sectors.

Turnover exhibits strong statistical significance across all financing categories (p < 0.01), indicating that revenue size is a critical determinant of financial diversification. High-revenue firms may benefit from a virtuous cycle: stronger income leads to better creditworthiness and investor confidence, which in turn facilitates access to alternative financing.

Regarding exports, significant relationships are observed primarily in the context of grants, other loans, and equity capital. This may reflect the existence of targeted public funding mechanisms and institutional investors focused on international expansion and market scaling.

Ownership structure proves to be significantly associated with all financing types, underscoring its central role in shaping financial strategy. Firms with diversified ownership (e.g., venture capital, partnerships) appear more capable or willing to pursue external, non-bank funding, while more centralized ownership models may prefer internal or debt-based financing to preserve control.

Finally, innovation shows statistically significant correlations across all financing types, reinforcing the idea that innovation-intensive firms have distinct financing needs and behaviors. Their dynamic nature, higher investment requirements, and long-term payoff profiles often make them more compatible with alternative financial instruments such as equity capital, subordinated loans, or innovation grants.

In conclusion, the data reveal robust and multifaceted relationships between firm characteristics and their likelihood of engaging in alternative financing. Structural dimensions such as firm size and turnover appear to have the most consistent influence, while strategic attributes like innovation and internationalization also play a key role. These findings support the view that alternative financing adoption is not random but patterned, offering valuable insights for policymakers, investors, and financial institutions seeking to promote diversified and inclusive access to capital.

4.3. Size and Age

To better understand the interactions between company size and age and the various alternative financing sources, a heatmap representation (Table 3) was used. This visualization highlights the probability of access, using green for the highest success rates and red for the least probable.

Table 3.

Probability of obtaining alternative financing: heatmaps. Source: Own elaboration based on SAFE survey data.

- The analysis of grants reveals a stable probability of 38% across all age categories. This suggests that, while the probability may vary depending on specific company size and age, overall access to this type of financing remains relatively balanced. Grants are typically aimed at innovative projects or expanding activities in strategic sectors. Larger companies may be perceived as more stable but also less dependent on such funds. In contrast, small and medium-sized companies, with more limited access to other forms of financing, are more likely to turn to grants. Companies aged between 2 and 5 years appear to be in an optimal phase for receiving grants, possessing sufficient track record and stability without having yet lost their innovative character or need for external support. This trend decreases in larger companies, which prefer other sources like bank loans or debt issuance, and in companies less than 2 years old, whose lack of history may limit their opportunities.

- Other Loans are particularly attractive to young or smaller companies that lack the necessary credit history to access more traditional funding sources. Young companies find these loans to be an accessible alternative compared to traditional bank loans, which require guarantees or a more extensive credit history. They are mainly used to cover short-term working capital needs due to their flexibility and accessibility. As companies grow, they tend to move away from more informal or short-term sources, shifting toward more structured options with more favorable terms.

- Debt Securities Issued requires a longer credit history, a higher credit rating, and greater administrative resources. Due to the lack of these characteristics, smaller companies often struggle to access this type of financing. While large companies have a higher likelihood of resorting to debt issuance, it is still less frequent compared to other funding sources. This may be because large companies already have more favorable financing routes and only resort to debt issuance when conditions are highly propitious, such as during periods of low-interest rates.

- Equity Financing involves sharing company ownership with investors. Small and medium-sized companies turn to this source of funding when they need capital to grow but do not have access to more traditional forms of financing. As companies grow, they tend to avoid ownership dilution and look for less invasive alternatives, such as loans or internal financing. Young companies have restricted access to debt due to their limited track record or lack of assets; in such cases, equity offers a way to obtain funding without the need for guarantees, but with the added cost of sharing ownership. Large companies primarily turn to equity at the start of their life cycle, as a source of financing for initial growth or expansion. However, as they stabilize, their focus shifts toward debt or more sophisticated funding sources that do not involve control dilution.

- Other Types of Financing (crowdfunding, peer-to-peer loans) are more commonly accessed by younger and smaller companies, with a noticeable decline in more mature companies. These sources are characterized by their lesser rigidity, more flexible requirements, and faster processes, making them particularly suitable for innovative companies with less reliance on tangible assets.

5. Discussion

Our research delves into the relationship between company characteristics and access to alternative financing sources, an area that complements the existing literature on traditional financing. While previous studies have shown that company size and age influence access to conventional financing, with larger and more mature companies tending to demonstrate greater solvency and, thus, better access (E. Brancati, 2015; Ferri & Murro, 2015; Avery et al., 1998), this study examines how these variables behave within the context of alternative financing.

The pecking order theory posits that companies prefer to fund their investments following a specific hierarchy. This hierarchy is based on information asymmetry, where managers avoid issuing shares if they believe the market undervalues them. Our results, by exploring alternative financing, allow us to analyze how this theory adapts to a new financial landscape.

5.1. Company Size, Age, and Access to Alternative Financing

The results of our analysis reveal a statistically significant relationship between company size (measured by the number of employees) and access to alternative financing sources. This allows us to reject the null hypothesis of independence between these variables, which aligns with findings from previous research on traditional financing by Cenni et al. (2015) and Kirschenmann (2016). Additionally, Appendix A provides a heatmap representation of the different financing sources according to the various categories of the analyzed business variables, offering a visual complement to these results.

This significant correlation holds true for most of the alternative sources analyzed, with the sole exception of “other types of financing,” where no significant size-based differences were observed. Overall, our data confirm that larger companies have easier access to alternative financing, reinforcing our initial hypothesis and aligning with the conclusions of prior studies by E. Brancati (2015), Cenni et al. (2015), Chavis et al. (2011), Farinha and Félix (2015), and Kirschenmann (2016). This finding aligns with the pecking order theory, as larger companies typically have lower risk and less information asymmetry, which facilitates their access to various alternative debt sources, thus avoiding the need to resort to equity financing.

Regarding company age, our findings present a more nuanced picture. We observe independence between age and access to financing in the case of grants and issued debt securities. This suggests that older companies do not present significant advantages in these categories, which contrasts with some previous studies that identify a positive correlation between age and access to financing (Comeig et al., 2015; Kirschenmann, 2016).

Conversely, for other loans and alternative financing types, younger companies are more likely to gain access. This finding is particularly relevant, as it could reflect the challenges faced by newly established companies in obtaining traditional bank financing. This difficulty leads them to seek alternative sources to structure their financing in the early stages of development, serving as a substitute for traditional financing (Allen et al., 2013). This result differs from studies that relate greater age to a higher probability of financing (Berger & Udell, 1998; Kirschenmann, 2016).

The preference of young companies for non-bank sources may be explained by the higher risk associated with their early stages, characterized by uncertain growth, supervisory challenges, and lower survival rates compared to more established firms (Chavis et al., 2011; Dierkes et al., 2013).

Additionally, age also influences equity financing. This type of financing is more common in the first five years of a company’s life and decreases significantly after ten years. This trend could be attributed to managers’ reluctance to relinquish control as the company matures (Vanacker & Manigart, 2010). These results, which differ from previous studies, offer useful guidance for young companies to select suitable financing sources in their early stages. The preference of younger firms for equity and other alternative loans represents a deviation from the traditional hierarchy. However, this deviation is consistent with the theory. Given that high information asymmetry and a lack of history prevent them from accessing traditional bank financing (debt), these firms are compelled to seek the next option in the pecking order: equity financing.

5.2. Sector of Activity and Access to Alternative Financing

The sector of activity is also a factor influencing access to financing, as it affects business risk and investment and financial requirements. Previous studies suggest that industrial companies, unlike those in services or commerce, face fewer restrictions when accessing external financing, primarily from banks.

Our study confirms a statistical relationship between the sector of activity and alternative financing sources. Specifically, grants, other types of financing, and equity funding are significantly related to the sector, while no such dependence was observed in the other alternative sources.

- Grants: Companies in the industrial sector show a higher probability of access, which can be explained by the high need for investment in infrastructure and tangible assets characteristic of this sector. This trend aligns with findings from studies on traditional bank financing by Cosh et al. (2009), Degryse et al. (2012), and Martínez et al. (2022), where larger collateral ensures better business performance and, therefore, increases the likelihood of fund repayment. Government policies supporting strategic sectors, such as manufacturing, further enhance access to grants.

- Equity Financing: The services sector shows a higher probability of access, attributable to the lower capital needs of companies in this sector compared to capital-intensive sectors. According to Harrison et al. (2004), sectors with lower initial capital requirements have less dependence on debt or tangible guarantees, which facilitates access to venture capital investors willing to take on higher risks in exchange for ownership stakes in the company. Conversely, the commerce sector faces more difficulties accessing equity financing, possibly due to its lower initial profitability and a reduced perception of high risk compared to more innovative or disruptive sectors. This result aligns perfectly with the pecking order theory. The lack of tangible assets in service-sector companies, which limits their collateral for debt, leads them to bypass the debt stage and proceed directly to equity financing due to information asymmetry.

- Other Types of Financing: The services sector again shows a higher probability of access, similar to equity financing. This pattern can be explained by the flexibility and agility of companies in this sector to adapt to innovative business models, such as equity crowdfunding, which favor companies with a more dynamic approach and less reliance on tangible assets. Companies in this sector often benefit from consumer trust and direct demand, which are key factors for success in these alternative financing models.

5.3. Revenue and Access to Alternative Financing

Revenue figures show a significant relationship with alternative financing sources. Companies with revenues between 2 and 50 million euros have a higher probability of obtaining grants. In contrast, companies with revenues under 500,000 euros or over 50 million euros have less access to this source. This preference of low-revenue companies for alternative loans aligns with the logic of the pecking order theory: unable to access traditional bank financing (debt), their second preferred option, they turn to alternative debt sources to avoid equity dilution.

This trend reverses in the case of “other loans” and “other types of financing,” such as peer-to-peer platforms, where companies with revenues under 500,000 euros have a higher probability of access. This difference contrasts with previous studies that showed greater restrictions for smaller companies, Block (2012) and Ferrando and Mulier (2015).

Financing through issued debt securities is relevant only for companies with revenues exceeding 50 million euros, which aligns with studies by Bongini et al. (2019) and Cosh et al. (2009). For equity financing, the probability increases from 10 million euros, decreasing in companies with revenues under 2 million euros (Degryse et al. (2012) and Ferrando and Mulier (2015)). The access to debt issuance by companies with higher revenues is clear evidence that these firms, with lower risk and information asymmetry, follow the traditional hierarchy, preferring debt over equity.

5.4. Export, Company Ownership, and Access to Alternative Financing

The export variable shows a significant relationship with alternative financing, allowing us to reject the null hypothesis of independence in the cases of grants, other loans, and equity funds. Thus, export-oriented companies have a higher probability of accessing grants, financing from other loans, and, to a lesser extent, equity financing. This factor facilitates access to these alternative financing sources, thereby expanding resources for business internationalization, in line with the findings of Huang and Liu (2017) and Wagner (2019).

The characteristics of company ownership show varied results, with financial managers’ and owners’ influence on capital structure (Chittenden et al., 1996; Ferrando & Griesshaber, 2011). Our results indicate a dependence between business ownership and alternative financing, as observed in previous studies by Ferrando and Griesshaber (2011) and Seghers et al. (2012).

- For grants, family-owned companies or those with multiple owners are more likely to obtain them. This aligns with the aversion to control dilution inherent in the pecking order theory. Family businesses, in particular, seek funding sources that do not involve bringing in new partners.

- In the case of other loans, companies with ownership via other companies, venture capital, or business angels are more successful.

- For debt securities issued, companies with shareholders, particularly those listed on the stock market, have a higher probability of access.

- Finally, for equity financing, companies with shareholders, other companies, and venture capital are the most likely to access these funds.

- In other types of financing, venture capital again shows the highest probability of success.

5.5. Innovation and Access to Alternative Financing

Finally, the innovation factor within the company, as a mechanism for differentiation and growth, shows a significant relationship with access to all forms of alternative financing. Companies that implement innovations or improvements in their products or services are more likely to access these sources. This not only allows them to increase their competitiveness in highly dynamic markets but also to capitalize on emerging market opportunities and scale their operations using digital technologies in the financial sector.

Innovation thus becomes a key growth driver and a differentiating strategy that attracts both private investors and crowdfunding platforms. In the current context, investors tend to seek innovative projects that offer high return potential and the possibility of disrupting established markets (Beyi, 2018; E. Brancati, 2015; Kaur & Kaur, 2021; Segal, 2016). This type of financing is particularly attractive to companies in early development stages that require capital for research and development (R&D) or the expansion of disruptive business models.

Moreover, digital technologies have transformed the landscape of alternative financing. Crowdfunding platforms and peer-to-peer loans have created new channels for innovative companies to obtain investment capital directly from individuals or small investors interested in financing projects with high disruptive potential. The ability to present innovative projects on online platforms has democratized access to financing, allowing companies with limited traditional resources but innovative ideas to capture the interest of a global audience.

In summary, the relationship between innovation and alternative financing is not only linked to companies’ competitiveness but also to their ability to adapt to new financial market dynamics. Innovative companies possess a significant competitive advantage, as their projects are more attractive to investors interested in emerging technologies and scalable business models. This connection strengthens the link between alternative financing sources and business innovation, fostering sustainable growth and the expansion of businesses with high disruptive potential. The preference of innovative firms for equity and other alternative sources deviates from the traditional hierarchy (internal > debt > equity). However, this pattern is fully consistent with the theory’s logic. Information asymmetry and the intangible nature of innovative firms’ assets make it difficult for them to access traditional bank debt.

Our research demonstrates that business characteristics such as size, age, sector of activity, and innovation significantly influence access to alternative financing sources. The findings are particularly insightful when viewed through the lens of the pecking order theory, which posits that firms prioritize internal financing, then debt, and finally equity. Our results suggest that while this traditional theory applies to conventional financing, its underlying logic holds true and adapts to the context of alternative financing.

We observe a clear adaptation of the theory: young and innovative companies, which often lack tangible assets and face high information asymmetry, are forced to “skip” the first steps of the hierarchy (internal financing and bank debt) and turn directly to venture capital and crowdfunding. In contrast, larger, more established companies follow a more traditional pattern, accessing alternative debt sources such as bond issuance.

In summary, alternative financing not only complements traditional sources but also acts as a mechanism that allows companies to navigate the financing hierarchy when conventional options are unavailable. This study not only validates the pecking order theory in a new context but also offers practical guidance for companies to select the most suitable financing sources based on their profile, thus driving innovation and sustainable growth in the dynamic business ecosystem.

6. Conclusions

The central premise of this research lies in addressing the persistent and multifaceted challenge that businesses globally face in accessing appropriate financing. This study, therefore, seeks to provide not only novel academic insight but also pragmatic solutions to this enduring issue within the business sector, particularly in an evolving economic landscape. Its significance is rooted in its contribution to bridging a notable gap in the existing scientific literature by rigorously examining emerging alternative financing mechanisms that possess significant potential to mitigate these challenges. Furthermore, a key contribution of this work is the development and empirical testing of a conceptual framework designed to identify and analyze the critical firm-level factors influencing the adoption and effectiveness of such mechanisms. These findings are particularly insightful when viewed through the lens of the pecking order theory, which posits a hierarchical preference for financing, beginning with internally generated funds, followed by debt, and concluding with equity. By doing so, this research aims to directly inform the design of more effective public policies aimed at fostering an enabling financial environment, as well as to guide more robust corporate strategies for capital acquisition. In an economic environment marked by profound uncertainty, rapid technological shifts, and the imperative for heightened resilience, this research offers not only a novel academic contribution to the finance and entrepreneurship fields but also serves as a strategic tool to promote sustainable economic development and significantly enhance business competitiveness across diverse European contexts.

The empirical findings from this study illuminate several crucial determinants of alternative financing access. Firstly, the findings unequivocally underscore company size as a key determinant, demonstrating a statistically significant positive correlation with access to most alternative financing sources. Larger firms are consistently more likely to utilize these alternatives, a finding that robustly reflects how size serves as a crucial proxy for financial stability, organizational maturity, and reduced perceived risk for financiers. This suggests that while alternative finance aims to democratize access, the inherent advantages of scale still play a significant role.

Secondly, although the relationship between company age and alternative financing is found to be less universally pronounced, the analysis reveals a distinct pattern: younger firms—particularly those within their first five years of existence—are notably more inclined to resort to other loans and equity financing. In contrast, more mature firms tend to show a decline in equity usage, a trend consistent with their reduced willingness to relinquish ownership control and their established access to traditional debt. These results collectively suggest that young companies strategically leverage alternative financing to overcome the inherent barriers in accessing traditional sources during their critical early development stages, where information asymmetries and collateral constraints are most acute. This behavior aligns with the pecking order theory, as their limited access to traditional bank debt forces them to move down the financing hierarchy to secure capital through alternative debt and, crucially, equity.

Thirdly, innovation emerges as one of the most influential factors, with a high level of statistical significance (p < 0.01) observed across multiple alternative financing types. Firms engaged in innovative activities frequently access equity and crowdfunding, successfully attracting investors who are specifically interested in high-growth, technology-driven, and disruptive ventures. The proliferation of digital platforms, such as peer-to-peer lending, has further democratized access to capital, specifically enabling resource-constrained, innovative companies to secure funding from a global and diversified pool of investors. These insights robustly highlight that innovation not only serves as a catalyst for business competitiveness but also critically facilitates entry into novel financing channels that are indispensable for supporting scalability and achieving sustainable growth. This strong preference for equity over debt among innovative firms is a key finding that reinforces the logic of the pecking order theory: their reliance on intangible assets and high information asymmetry makes traditional debt less viable, compelling them to turn to risk-tolerant equity investors as a primary source of funding.

Fourthly, ownership structure is found to significantly influence alternative financing adoption. Companies backed by venture capital exhibit the highest success rates in securing alternative funds (69.9%), underscoring the proactive role external equity investors often play in encouraging diversified capital structures. Conversely, single-owner firms are considerably less likely to access these sources (50.5%), a pattern that might be attributed to their often more conservative financial culture, limited administrative capacity, or heightened aversion to external control. Furthermore, family-owned businesses notably capitalize on grants by leveraging governmental and public support programs, reflecting their specific strategic alignments.

Fifthly, sectoral activity also distinctly shapes firms’ financing needs and available options. For example, industrial firms display a high probability of accessing grants (62.4%), a propensity often driven by their capital-intensive investments in tangible assets and alignment with strategic industrial policies. In parallel, the service sector leads in equity and crowdfunding uptake due to its inherently greater flexibility and adaptability to innovative, less asset-heavy business models. Conversely, the trade sector demonstrates comparatively lower engagement with alternative financing (49.3%), a finding consistent with its relatively lower capital intensity and often shorter operational cycles.

Sixthly, company revenue serves as a strong and consistent predictor of alternative financing access. Higher-revenue firms are more likely to obtain grants and engage in debt issuance, indicating a greater level of confidence from a broader range of financiers, including traditional ones who might co-invest or structure hybrid deals. Conversely, firms with revenues below EUR 500,000 find crowdfunding and other loans more accessible, underscoring the critical and enabling role of alternative financing for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs)—particularly nascent firms—in securing vital resources to scale operations and consolidate their value propositions. This highlights how alternative financing acts as a crucial bridge for businesses unable to meet traditional lending criteria.

Finally, internationalization is also closely linked to alternative financing usage. Export-oriented companies exhibit a higher propensity to seek grants and equity funding, reflecting specific and often substantial capital needs associated with navigating the complexities of global expansion. These findings emphasize how direct exposure to international markets fosters the adoption of more flexible, diversified, and risk-tolerant financial models, essential for supporting cross-border trade and investment.

In sum, this study rigorously demonstrates that structural factors such as innovation capacity, firm size, and sectoral characteristics significantly influence access to alternative financing. These sources not only fundamentally diversify capital options for businesses but also exhibit a remarkable adaptability to companies of varying sizes, sectors, and maturity levels. The comprehensive results provide valuable, empirically backed guidance for businesses aiming to optimize their financial strategies in a dynamic environment, and concurrently offer a robust foundation for further academic inquiry into how diverse business characteristics affect capital structure decisions and financial resilience.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

Nevertheless, this study, despite its comprehensive scope, possesses certain inherent limitations that warrant acknowledgment and suggest avenues for future inquiry. Firstly, the dataset exclusively pertains to European countries, specifically excluding major global economies such as the United Kingdom and the United States. This geographical focus, while providing depth for Europe, inherently limits a broader understanding of alternative financing dynamics in more mature or distinct financial markets. The inclusion of these regions in future comparative studies could undoubtedly reveal important international variations and provide a more generalized perspective on the drivers and barriers to alternative finance.

Secondly, a notable limitation is the absence of gender-related data concerning financial decision-makers within businesses. This omission constrains a more granular analysis, as prior research suggests that this factor may significantly affect financing access and deserves substantial consideration. Integrating this perspective in future research would provide a more inclusive and nuanced understanding of the diverse factors influencing business financial strategies and potentially uncover new dimensions of financial inequality.

Building upon these insights and limitations, several promising future research directions emerge. Firstly, future research could benefit from employing more advanced multivariate analyses to examine the complex interplay between multiple firm-specific, industry-level, and macroeconomic factors and the choice of alternative financing. Such analyses could reveal subtle interactions and dependencies that are not apparent in bivariant studies, providing a more holistic understanding of the drivers behind firms’ financing decisions.

Secondly, longitudinal studies would be invaluable to track the evolving access to alternative financing sources over extended periods. Such studies could offer deeper insights into shifting financing preferences, the persistence of specific barriers that businesses encounter, and how various public policies and regulatory changes impact the accessibility and adoption of these resources across economic cycles.

Thirdly, an impactful line of research would involve conducting comparative analyses between different countries or specific regions with distinct financial ecosystems and regulatory frameworks. This approach would elucidate how broader socioeconomic, cultural, and regulatory factors shape firms’ access to alternative financing, and how businesses in diverse geographies leverage various financing sources uniquely. A rigorous comparative methodology could also facilitate the identification of best practices and policy interventions that other countries or regions might adopt to improve access to alternative financing for their businesses.

Finally, investigating the specific impact of governmental policies and regulatory frameworks—both those designed to promote and those that inadvertently constrain alternative financing—represents a critical avenue for ongoing inquiry. This research should be tailored to consider the different economic contexts and the specific characteristics of businesses within each region, assessing how policy interventions either facilitate market development or create unintended barriers for innovative financing solutions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: J.M.L., I.M.-C. and G.R.G.; methodology, J.M.L., I.M.-C. and G.R.G.; formal analysis, J.M.L.; investigation, J.M.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.M.L.; writing—review and editing, J.M.L., I.M.-C. and G.R.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data utilized in this study were obtained, with prior authorization from the European Central Bank, from the information provided by the SAFE survey. Access to the data can be requested via the following web address: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/stats/ecb_surveys/safe/html/index.en.html (accessed on 10 January 2025).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the European Central Bank for providing the data from the Survey on the Access to Finance of Enterprises (SAFE). They also thank the editors and the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments on the initial version of the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Post hoc results of the chi-square statistic relating firm characteristics to funding sources. Blue cells indicate higher access and red cells indicate lower access, with color intensity proportional to the level of statistical significance.

References

- Allen, F., Carletti, E., & Valenzuela, P. (2013). Financial intermediation, markets, and alternative financial sectors. In Handbook of the economics of finance (Vol. 2, pp. 759–798). North Holland Publisher. [Google Scholar]

- Avery, R. B., Bostic, R. W., & Samolyk, K. A. (1998). The role of personal wealth in small business finance. Journal of Banking & Finance, 22(6–8), 1019–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, J., & Silverman, B. (2004). Picking winners or building them? Alliance, intellectual, and human capital as selection criteria in venture financing and performance of biotechnology startups. Journal of Business Venturing, 19(3), 411–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, A. N., & Udell, G. F. (1998). The economics of small business finance: The roles of private equity and debt markets in the financial growth cycle. Journal of Banking and Finance, 22(6–8), 613–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyi, W. A. (2018). The trilogy of a digital communication between the real man, his digital individual and the market of the digital economy. SocioEconomic Challenges, 2(2), 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, J. H. (2012). R&D investments in family and founder firms: An agency perspective. Journal of Business Venturing, 27, 248–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongini, P., Ferrando, A., Rossi, E., & Rossolini, M. (2019). SME access to market-based finance across eurozone countries. Small Business Economy, 56, 1667–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brancati, E. (2015). Innovation financing and the role of relationship lending for SMEs. Small Business Economics, 44(2), 449–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brancati, R., Marrocu, E., Romagnoli, M., & Usai, S. (2018). Innovation activities and learning processes in the crisis: Evidence from Italian export in manufacturing and services. Industrial and Corporate Change, 27(1), 107–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruton, G., Khavul, S., Siegel, D., & Wright, M. (2015). New financial alternatives in seeding entrepreneurship: Microfinance, crowdfunding, and peer-to-peer innovations. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(1), 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkart, M., & Ellingsen, T. (2004). In-kind finance: A theory of trade credit. American Economic Review, 94(3), 569–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, E., & O’Toole, C. M. (2014). Bank lending constraints, trade credit and alternative financing during the financial crisis: Evidence from European SMEs. Journal of Corporate Finance, 27, 173–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassar, G. (2004). The financing of business start-ups. Journal of Business Venturing, 19(2), 261–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalluzzo, K. S., Cavalluzzo, L. C., & Wolken, J. D. (2002). Competition, small business financing, and discrimination: Evidence from a new survey. The Journal of Business, 75(4), 641–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenni, S., Monferrà, S., Salotti, V., Sangiorgi, M., & Torluccio, G. (2015). Credit rationing and relationship lending. Does firm size matter? Journal of Banking & Finance, 53, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavis, L. W., Klapper, L. F., & Love, I. (2011). The impact of the business environment on young firm financing. The World Bank Economic Review, 25(3), 486–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chittenden, F., Hall, G., & Hutchinson, P. (1996). Small firm growth, access to capital markets and financial structure: Review of issues and an empirical investigation. Small Business Economics, 8, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y., & Lee, J. (2018). Entrepreneurial orientation, entrepreneurial education and performance. Asia Pacific Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 12(2), 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comeig, I., Fernández-Blanco, M. O., & Ramírez, F. (2015). Information acquisition in SME’s relationship lending and the cost of loans. Journal of Business Research, 68(7), 1650–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosh, A., Cumming, D., & Hughes, A. (2009). Outside enterpreneurial capital. The Economic Journal, 119(540), 1494–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degryse, H., De Goeij, P., & Kappert, P. (2012). The impact of firm and industry characteristics on small firms’ capital structure. Small Business Economics, 38, 431–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]