Social Preference Parameters Impacting Financial Decisions Among Welfare Recipients

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Games

1.2. Ultimatum Game

1.3. Dictator Game

1.4. Trust Game

1.5. Benchmarking with Prior Student–City Comparisons

2. Experimental Procedures

Subject Pools and Background

3. Results

3.1. The Ultimatum Game

3.2. The Dictator Game

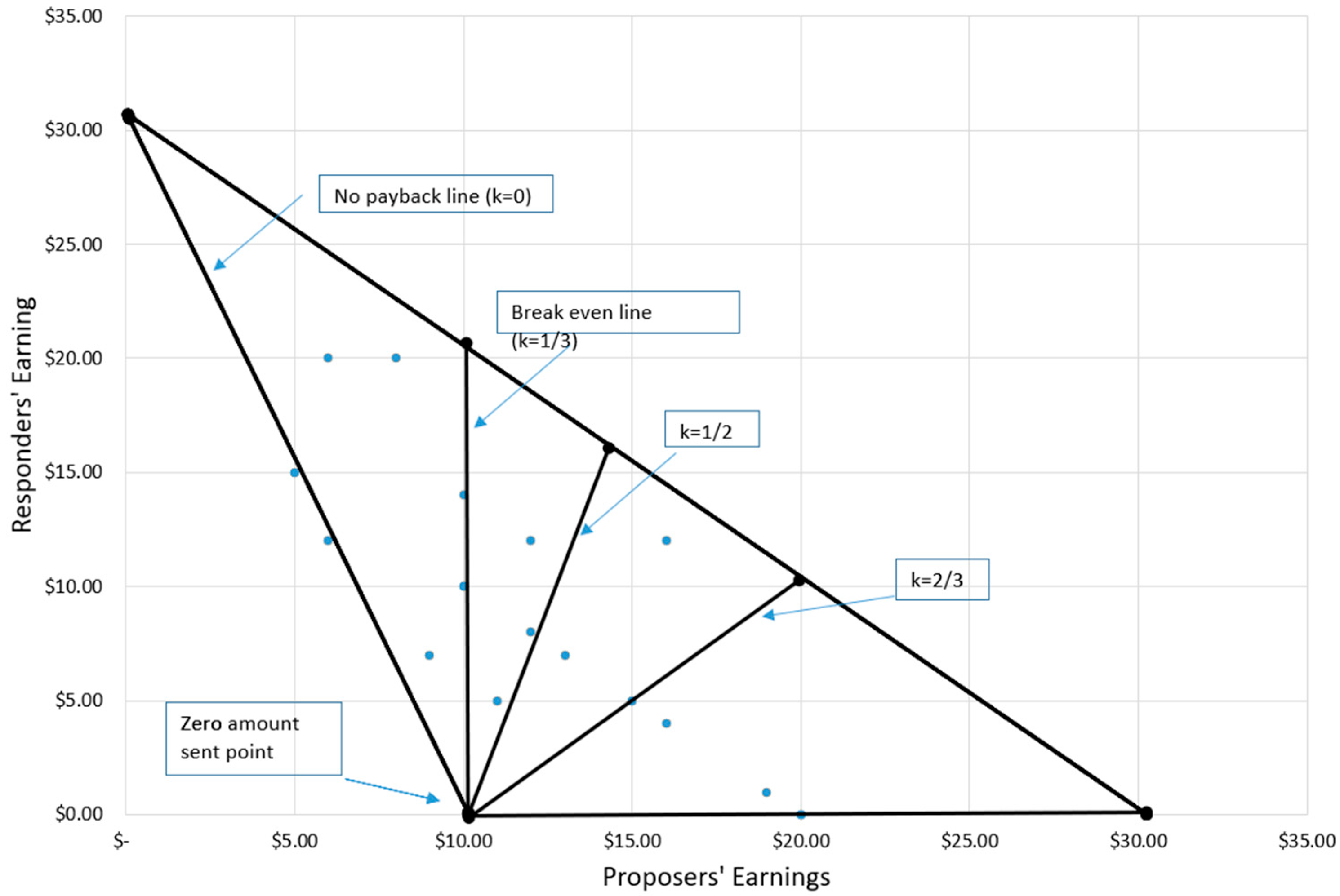

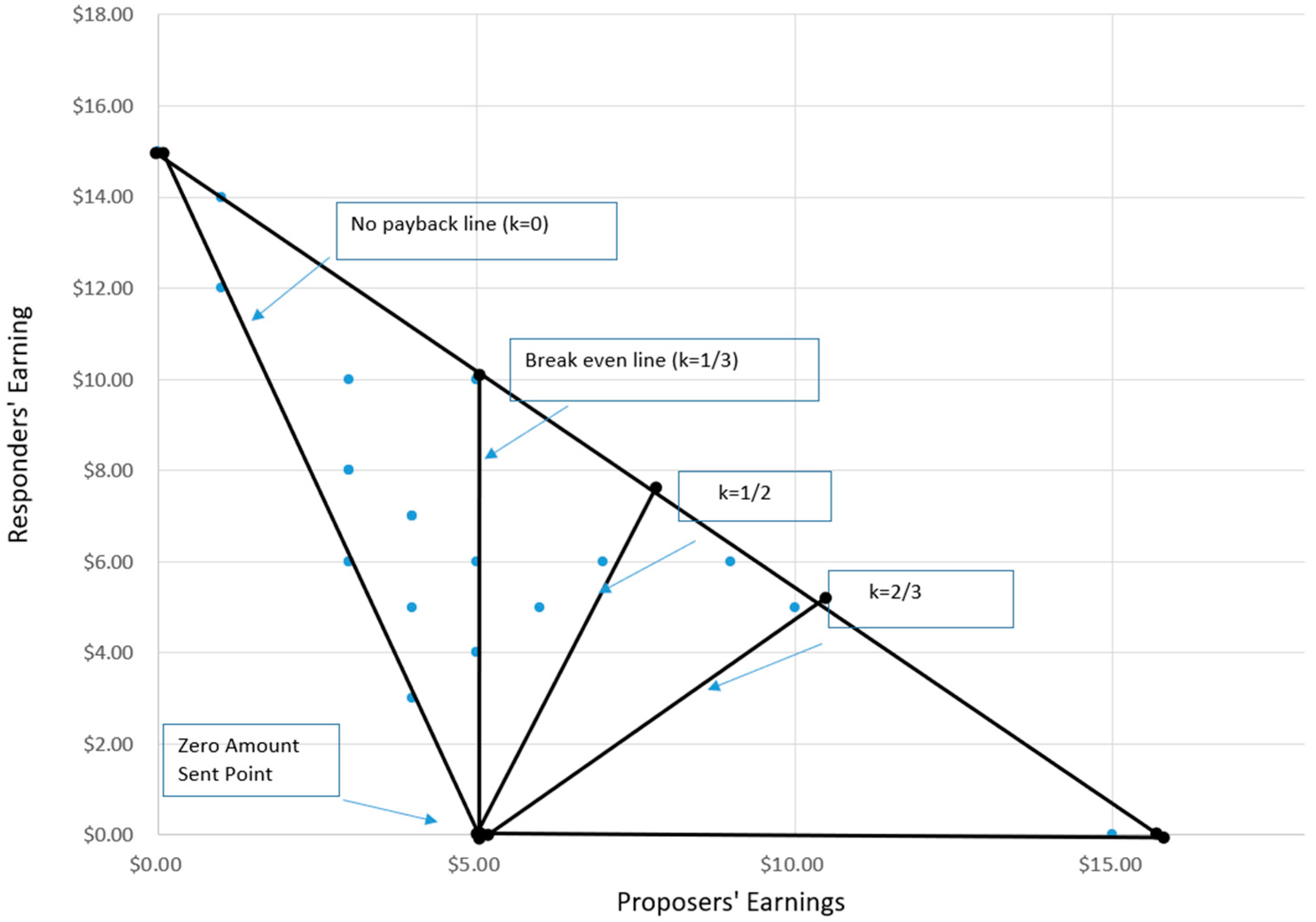

3.3. The Trust Game

3.4. Reciprocity Analysis

3.5. Pooled-Sample Robustness Check

3.6. Robustness and External Validation: Matching, Weighting, and Benchmark Comparisons

3.6.1. Exact Matching on Observed Covariates

3.6.2. Propensity Score Matching (PSM) and Inverse-Probability Weighting (IPW)

3.6.3. External Triangulation with Published Adult Samples

3.6.4. Payback Decision and Earnings for the Miami and Tucson Samples

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al-Ubaydli, O., List, J. A., & Suskind, D. (2023). Behavioral economics and child development. Journal of Political Economy, 131(2), 321–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvard, M. (2004). The ultimatum game, fairness, and cooperation among big game hunters. In J. Henrich, R. Boyd, S. Bowles, C. Camerer, E. Fehr, & H. Gintis (Eds.), Foundations of human sociality (pp. 413–435). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, S., Ertac, S., Gneezy, U., Hoffman, M., & List, J. A. (2011). Stakes matter in ultimatum games. American Economic Review, 101(7), 3427–3439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, N., Bohnet, I., & Piankov, N. (2006). Decomposing trust and trustworthiness. Experimental Economics, 9(3), 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athey, S., & Imbens, G. (2019). Machine learning methods economists should know about. Annual Review of Economics, 11, 685–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellemare, C., Kröger, S., & Van Soest, A. (2008). Measuring inequity aversion in a heterogeneous population using experimental decisions and subjective probabilities. Econometrica, 76(4), 815–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belot, M., Duch, R., & Miller, L. (2015). A comprehensive comparison of students and non-students in classic experimental games. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 113, 26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, J., Dickhaut, J., & McCabe, K. (1995). Trust, reciprocity, and social history. Games and Economic Behavior, 122–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, M., Mullainathan, S., & Shafir, E. (2004). A behavioral-economics view of poverty. American Economic Review, 94(2), 419–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blattman, C., Green, E. P., Jamison, J., Lehmann, M. C., & Annan, J. (2020). The returns to microenterprise support among the ultra-poor: A field experiment in post-war Uganda. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 12(4), 160–195. [Google Scholar]

- Bohnet, I., & Zeckhauser, R. (2004). Trust, risk and betrayal. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 55(4), 467–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, G. E., Katok, E., & Zwick, R. (1998). Dictator game giving: Rules of fairness versus acts of kindness. International Journal of Game Theory, 27(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, G. E., & Ockenfels, A. (2000). A theory of equity, reciprocity, and competition. American Economic Review, 90(1), 166–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brulhart, M. (2012). Does the trust game measure trust? Economics Letters, 115(1), 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camerer, C. F. (2003). Behavioral game theory: Experiments in strategic interaction. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, J. C. (2004). How to identify trust and reciprocity. Games and Economic Behavior, 46(2), 260–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, J. C., Friedman, D., & Gjerstad, S. (2007). A tractable model of reciprocity and fairness. Games and Economic Behavior, 59(1), 17–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croson, R., & Gneezy, U. (2009). Gender differences in preferences. Journal of Economic Literature, 47(2), 448–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DellaVigna, S. (2009). Psychology and economics: Evidence from the field. Journal of Economic Literature, 47(2), 315–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohmen, T., Falk, A., Huffman, D., & Sunde, U. (2011). The intergenerational transmission of risk and trust attitudes. Review of Economic Studies, 79(2), 645–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, C. (2011). Dictator games: A meta study. Experimental Economics, 14(4), 583–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exadaktylos, F., Espín, A. M., & Branas-Garza, P. (2013). Experimental subjects are not different. Scientific Reports, 3(1), 1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falk, A., Fehr, E., & Fischbacher, U. (2008). Testing theories of fairness—Intentions matter. Games and Economic Behavior, 62(1), 287–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehr, E., & Fischbacher, U. (2002). Why social preferences matter—The impact of non-selfish motives on competition, cooperation and incentives. Economic Journal, 112(478), C1–C33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehr, E., & Gächter, S. (2000). Fairness and retaliation: The economics of reciprocity. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 14(3), 159–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehr, E., & Schmidt, K. M. (1999). A theory of fairness, competition, and cooperation. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114(3), 817–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischbacher, U., & Gächter, S. (2010). Social preferences, beliefs, and the dynamics of free riding. American Economic Review, 100(1), 541–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsythe, R., Horowitz, J. L., Savin, N. E., & Sefton, M. (1994). Fairness in simple bargaining experiments. Games and Economic Behavior, 6, 347–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gächter, S., & Herrmann, B. (2009). Reciprocity, culture and human cooperation: Previous insights and a new cross-cultural experiment. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 364(1518), 791–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gintis, H., Bowles, S., Boyd, R., & Fehr, E. (Eds.). (2005). Moral sentiments and material interests: The foundations of cooperation in economic life. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Glaeser, E. L., Laibson, D. I., Scheinkman, J. A., & Soutter, C. L. (2000). Measuring trust. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115(3), 811–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, D., & Pallais, A. (2015). Experimental evidence on the productivity, profitability, and limits of labor flexibility. Review of Economic Studies, 82(2), 41–76. [Google Scholar]

- Gneezy, U., Leibbrandt, A., & List, J. A. (2016). Ode to the sea: Workplace organizations and norms of cooperation. The Economic Journal, 126(595), 1856–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, W. H. (2020). Econometric analysis (8th global ed.). Pearson Education Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Gummerum, M., Hanoch, Y., Keller, M., Parsons, K., & Hummel, A. (2010). Preschoolers’ allocations in the dictator game: The role of moral emotions. Journal of Economic Psychology, 31(1), 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güth, W., Schmittberger, R., & Schwarze, B. (1982). An experimental analysis of ultimatum bargaining. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 3(4), 367–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrich, J., Boyd, R., Bowles, S., Camerer, C., Fehr, E., Gintis, H., & McElreath, R. (2001). In search of Homo economicus: Behavioral experiments in 15 small-scale societies. American Economic Review, 91(2), 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, C. A. (2019). Markets, games, & strategic behavior: An introduction to experimental economics (2nd ed.). Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Holt, C. A., & Laury, S. K. (2002). Risk aversion and incentive effects. American Economic Review, 92(5), 1644–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, N. D., & Mislin, A. A. (2011). Trust games: A meta-analysis. Journal of Economic Psychology, 32(5), 865–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J. L., & Thaler, R. H. (1986). Fairness and the assumptions of economics. The Journal of Business, 59(4), S285–S300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullainathan, S., & Shafir, E. (2013). Scarcity: Why having too little means so much. Times Books. [Google Scholar]

- Oosterbeek, H., Sloof, R., & van de Kuilen, G. (2004). Cultural differences in ultimatum game experiments: Evidence from a meta-analysis. Experimental Economics, 7(2), 171–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanfey, A. G., Rilling, J. K., Aronson, J. A., Nystrom, L. E., & Cohen, J. D. (2003). The neural basis of economic decision-making in the ultimatum game. Science, 300(5626), 1755–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sauermann, J. (2023). Worker reciprocity and the returns to training: Evidence from a field experiment. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 32(3), 543–557. [Google Scholar]

- Small, M. L., & Newman, K. S. (2001). Urban poverty after The Truly Disadvantaged: The rediscovery of the family, the neighborhood, and culture. Annual Review of Sociology, 27, 23–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staffiero, G., Exadaktylos, F., & Espín, A. M. (2013). Accepting zero in the ultimatum game does not reflect selfish preferences. Economics Letters, 121(2), 236–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Thaler, R. H. (2016). Behavioral economics: Past, present, and future. American Economic Review, 106(7), 1577–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ultimatum Game: Envy and Self-interest | ||||||||||

| Miami | Tucson | |||||||||

| All Miami | Male | Female | Hispanic/Latino | Non-Hispanic/Latino | All Tucson | Male | Female | Hispanic/Latino | Non-Hispanic/Latino | |

| Avg % Amount offered | 0.42 | 0.45 | 0.39 | 0.43 | 0.41 | 0.4 | 0.39 | 0.41 | 0.37 | 0.41 |

| % of Offers Rejected | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.09 |

| Dictator Game: Altruism and Self-interest | ||||||||||

| Miami | Tucson | |||||||||

| All Miami | Male | Female | Hispanic/Latino | Non-Hispanic/Latino | All Tucson | Male | Female | Hispanic/Latino | Non-Hispanic/Latino | |

| Avg % Amount Offered | 0.23 | 0.18 | 0.27 | 0.25 | 0.14 | 0.22 | 0.21 | 0.25 | 0.26 | 0.21 |

| Trust Game: Trust, Trustworthiness, and Positive Reciprocity | ||||||||||

| Miami | Tucson | |||||||||

| All Miami | Male | Female | Hispanic/Latino | Non-Hispanic/Latino | All Tucson | Male | Female | Hispanic/Latino | Non-Hispanic/Latino | |

| Avg % Amount Passed | 0.56 | 0.53 | 0.63 | 0.53 | 0.58 | 0.54 | 0.39 | 0.68 | 0.51 | 0.55 |

| Avg % Amount that the Trustee Returns | 0.52 | 0.44 | 0.53 | 0.50 | 0.55 | 0.45 | 0.36 | 0.55 | 0.40 | 0.47 |

| t-Test for Equality of Means | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t | df | Sig. (2-Tailed) | Mean Difference | Std. Error Difference | 95% Confidence Interval of the Difference | ||

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Ultimatum Average % Amount Offered | |||||||

| Gender | 0.734 | 55 | 0.466 | 0.02955 | 0.04023 | −0.05108 | 0.11017 |

| Ethnicity | −0.139 | 55 | 0.890 | −0.00554 | 0.03992 | −0.08554 | 0.07446 |

| Location | 0.403 | 55 | 0.688 | 0.01607 | 0.03987 | −0.06382 | 0.09597 |

| Ultimatum % of Offers Rejected | |||||||

| Gender | 0.839 | 55 | 0.405 | 0.06439 | 0.07677 | −0.08945 | 0.21824 |

| Ethnicity | −1.447 | 55 | 0.154 | −0.10837 | 0.07489 | −0.25845 | 0.04170 |

| Location | −0.420 | 55 | 0.676 | −0.03202 | 0.07618 | −0.18468 | 0.12064 |

| Dictator Avg % Amount Offered | |||||||

| Gender | 0.295 | 55 | 0.769 | 0.01629 | 0.05523 | −0.09440 | 0.12698 |

| Ethnicity | 1.020 | 55 | 0.312 | 0.05517 | 0.05408 | −0.05321 | 0.16356 |

| Location | −0.239 | 55 | 0.812 | −0.01305 | 0.05456 | −0.12240 | 0.09629 |

| Trust—Avg % Amount Sent | |||||||

| Gender | −2.312 | 51 | 0.025 | −0.18035 | 0.07801 | −0.33697 | −0.02374 |

| Ethnicity | −0.538 | 51 | 0.593 | −0.04343 | 0.08071 | −0.20546 | 0.11860 |

| Location | −0.209 | 51 | 0.835 | −0.01695 | 0.08113 | −0.17984 | 0.14593 |

| Trust—Avg % Amount Returned | |||||||

| Gender | 1.838 | 51 | 0.072 | 0.18636 | 0.10139 | −0.01718 | 0.38991 |

| Ethnicity | −0.098 | 51 | 0.922 | −0.01014 | 0.10333 | −0.21758 | 0.19729 |

| Location | 0.548 | 51 | 0.586 | 0.05661 | 0.10333 | −0.15083 | 0.26405 |

| Ultimatum | Dictator | Trust | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avg % Amount Offered | Offers Rejected | Avg % Amount Offered | Avg % Amount Sent | Avg % Amount Returned | |

| Location | 0.033 (0.049) | 0.050 (0.091) | −0.060 (0.066) | −0.027 (0.092) | 0.120 (0.119) |

| Gender | 0.033 (0.041) | 0.069 (0.077) | 0.010 * (0.056) | −0.185 * (0.080) | 0.203 * (0.104) |

| Ethnicity | −0.023 (0.048) | −0.134 (0.090) | 0.088 0.065 | −0.035 (0.091) | −0.065 (0.117) |

| Constant | 0.389 *** (0.036) | 0.103 (0.068) | 0.209 *** (0.049) | 0.657 *** (0.068) | 0.370 *** (0.088) |

| R2 | 0.018 | 0.054 | 0.035 | 0.103 | 0.081 |

| Observations | 56 | 56 | 56 | 56 | 56 |

| Dependent Variable | Location Main Effect | Largest Interaction Term | Adjusted R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ultimatum—% offered | β = −0.012, p = 0.32 | Location × Gender: β = 0.018, p = 0.28 | 0.07 |

| Dictator—% offered | β = 0.004, p = 0.73 | Location × Gender: β = −0.021, p = 0.19 | 0.05 |

| Trust—% sent | β = −0.015, p = 0.27 | Location × Stakes: β = 0.029, p = 0.14 | 0.08 |

| Reciprocity—% returned | β = −0.022, p = 0.21 | Location × Gender: β = 0.034, p = 0.11 | 0.06 |

| Covariate | Raw Mean Welfare (N = 56) | Raw Mean Students (N = 58) | SMD Raw |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male (1 = Yes) | 0.38 | 0.41 | −0.08 |

| Hispanic (1 = Yes) | 0.62 | 0.22 | 0.81 |

| Game | Loc β PSM | p PSM | Gender β PSM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ultimatum | −0.015 | 0.3 | 0.052 |

| Dictator | 0.006 | 0.7 | 0.037 |

| Trust | −0.018 | 0.28 | 0.06 |

| Reciprocity | −0.025 | 0.24 | 0.072 |

| Game Metric | Welfare Recipients Mean | Adult Mean (95% CI) (Belot et al., 2015) | Adult Mean (95% CI) (Staffiero et al., 2013) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ultimatum—% Offered | 0.38 | 0.32 (0.28–0.36) | 0.35 (0.30–0.40) |

| Dictator—% Offered | 0.29 | 0.28 (0.24–0.31) | 0.27 (0.23–0.31) |

| Trust—% Sent | 0.37 | 0.35 (0.31–0.38) | 0.36 (0.32–0.40) |

| Reciprocity—% Returned | 0.35 | 0.34 (0.30–0.38) | 0.33 (0.29–0.37) |

| Diagnostic | Ultimatum | Dictator | Trust | Reciprocity | Benchmark |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean VIF (Location, Gender, Ethnicity, Stakes-ratio) | 1.18 | 1.21 | 1.23 | 1.19 | p < 5 indicates no multicollinearity (Greene, 2020) |

| Shapiro–Wilk p (normality of residuals) | 0.22 | 0.31 | 0.18 | 0.27 | p > 0.05 p ⇒ cannot reject normality |

| Breusch–Pagan p (heteroskedasticity) | 0.34 | 0.29 | 0.41 | 0.36 | p > 0.05 p > 0.05 ⇒ homoscedastic errors |

| Max Cook’s D | 0.12 | 0.1 | 0.09 | 0.11 | p < 1 ⇒ no influential outliers |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zumaeta, J.N. Social Preference Parameters Impacting Financial Decisions Among Welfare Recipients. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 408. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18080408

Zumaeta JN. Social Preference Parameters Impacting Financial Decisions Among Welfare Recipients. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(8):408. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18080408

Chicago/Turabian StyleZumaeta, Jorge N. 2025. "Social Preference Parameters Impacting Financial Decisions Among Welfare Recipients" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 8: 408. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18080408

APA StyleZumaeta, J. N. (2025). Social Preference Parameters Impacting Financial Decisions Among Welfare Recipients. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(8), 408. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18080408