Economic Attitudes and Financial Decisions Among Welfare Recipients: Considerations for Workforce Policy

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Tasks

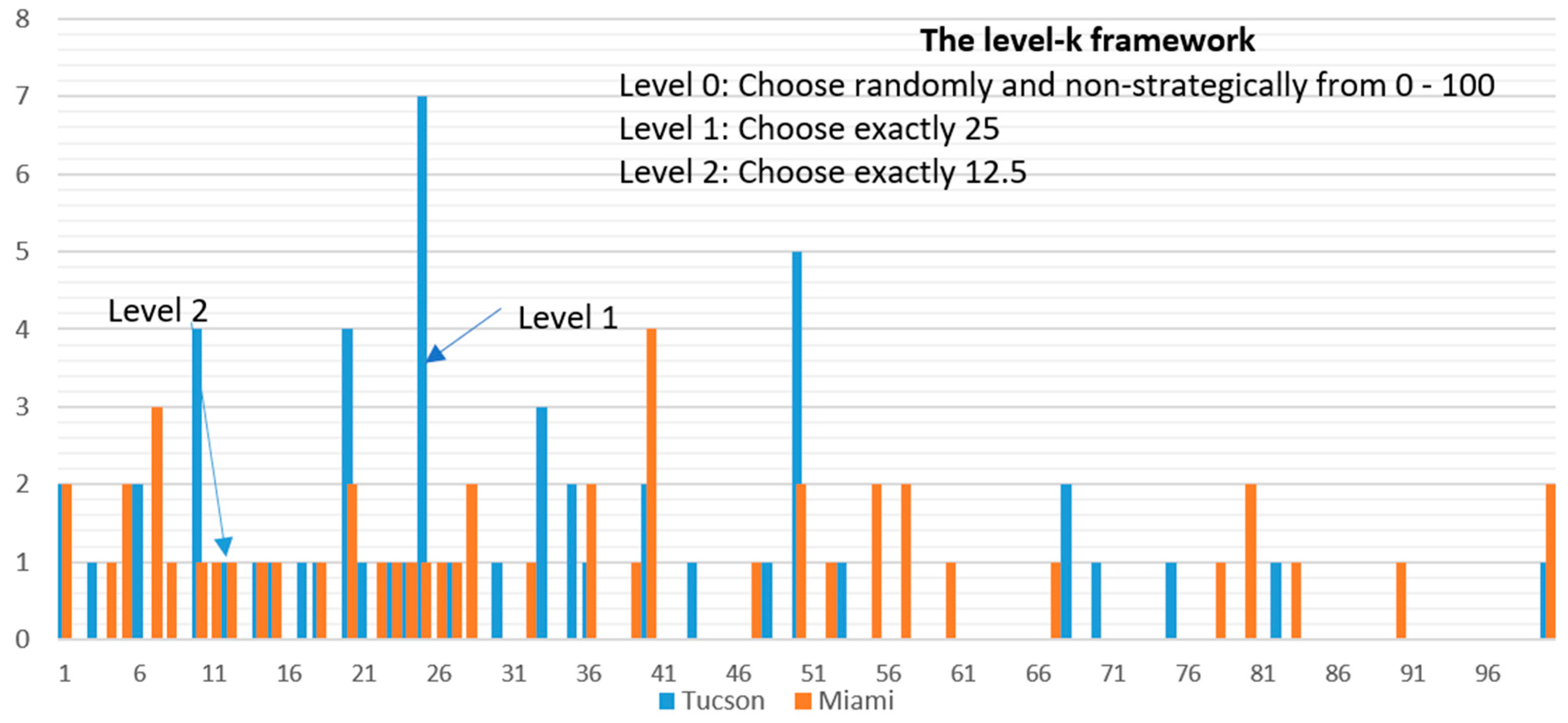

1.2. The Guessing Game: Measuring Strategic Thinking and Perceived Rationality

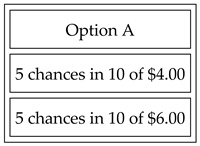

1.3. Prudence Measurement Task: Assessing Caution in Decision-Making

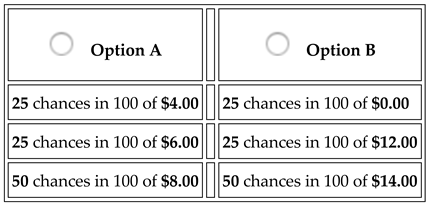

1.4. Risk Aversion Measurement Task: Evaluating Risk Preferences

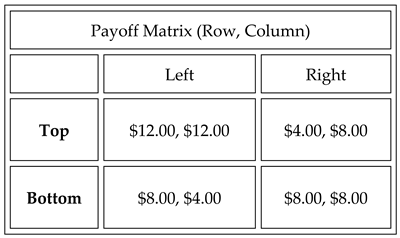

1.5. The Stag Hunt Game: Coordination and Strategic Uncertainty

2. Experimental Procedures

2.1. Session Structure and Compensation

2.2. Data Collection and Coding

2.3. Consideration of Order Effects

3. Results

3.1. The Guessing Game—Strategic Thinking and Perceived Rationality of Others (Average Guess)

3.2. Prudence Measurement Task—(Avg % Prudent Choices)

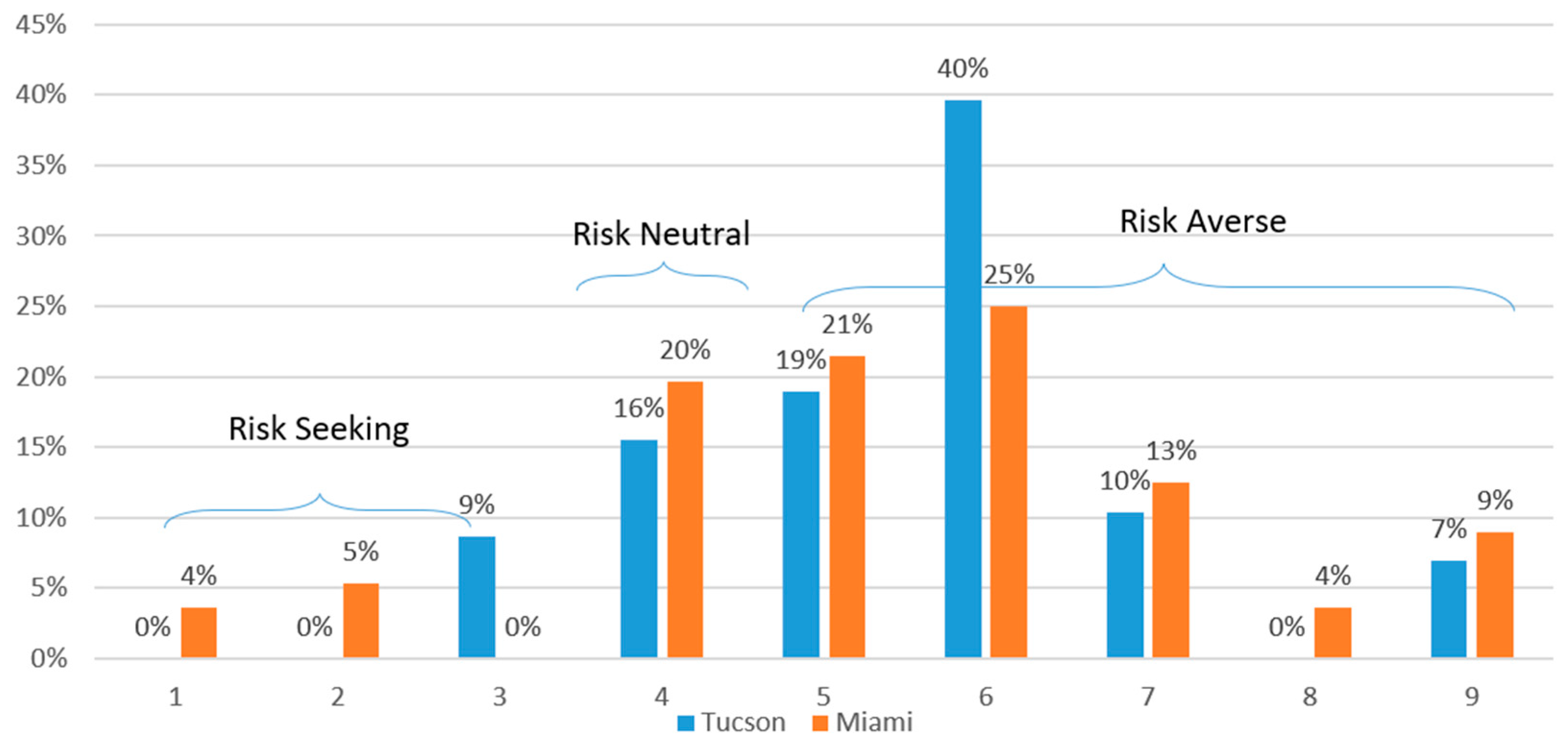

3.3. Risk Aversion—Number of Safe Choices

3.4. Stag Hunt—Percent of Playing Pareto Optimal Action

4. Conclusions

5. Discussion

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Decisions: At the beginning of each round, you will be asked to choose a number between (and including) 0.00 to 100.00. At the same time, the 5 people who are matched with you also choose a number between (and including) 0.00 to 100.00. None of you has each other’s number.

- Draws: If more than one person tied by having a number which is close to the final number, then the payment of $ 20.00 is divided equally among those who tied. The others win $ 0.00

- Gains: The six selected numbers will be averaged, and then a fraction (half) of the average will be calculated and announced. The person whose number is close to half the average will earn $ 20.00. The others earn $ 0.00.

- Subsequent Pairings: The group of 6 are the same in all subsequent rounds, then the people with whom you are paired in a round will be the same people who will be paired with you in the next round

- Subsequent Parts: This whole process (making 2 decisions and having one selected at random to determine your earnings) will be repeated once, with some changes in the structure of the options themselves in the second part. Earnings for each decision will not be released until you finish the final part.

- Earnings Record: The computer keeps track of your earnings, i.e., the sum of the amounts earned in each part

- Remember: the first round will be a round of practice for you to understand the game, therefore will not be taken into account towards your earnings and the second round will be the round that we will consider for your earnings.

- Determining the Payoff for Each Round: After one of the decisions has been randomly selected, the computer will generate another random number that corresponds to the throw of a ten sided die. The number is equally likely to be 1, 2, 3, … 10. This random number determines your earnings for the Option (A or B) that you previously selected for the decision being used.

- Remember: the first round will be a round of practice for you to understand the game, therefore will not be taken into account towards your earnings. The second round will be the round that we will consider for your earnings.

References

- André, E., Bommier, A., & Le Grand, F. (2022). The impact of risk aversion and ambiguity aversion on annuity and saving choices. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 65(1), 33–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avramopoulos, I. (2018). On incremental deployability. arXiv, arXiv:1805.10115. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, I. S., Melania, M., & Agustina, H. (2020). The role of psychological testing as an effort to improve employee competency. GATR Journal of Management and Marketing Review, 5(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belot, M., Duch, R., & Miller, L. (2015). A comprehensive comparison of students and non-students in classic experimental games. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 113, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilancini, E., Boncinelli, L., & Mattiassi, A. (2019). Assessing actual strategic behavior to construct a measure of strategic ability. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosch-Domenech, A., Montalvo, J. G., Nagel, R., & Satorra, A. (2002). One, two, (three), infinity, …: Newspaper and lab beauty-contest experiments. American Economic Review, 92(5), 1687–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozeman, B. (2022). Rules compliance behavior: A heuristic model. Perspectives on Public Management and Governance, 5(1), 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breen, R., van de Werfhorst, H. G., & Jaeger, M. M. (2014). Deciding under doubt: A theory of risk aversion, time discounting preferences, and educational decision-making. European Sociological Review, 30(2), 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunette, M., & Jacob, J. (2019). Risk aversion, prudence, and temperance: An experiment in gain and loss. Research in Economics, 73(2), 174–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camerer, C. (2011). The promise and success of lab-field generalizability in experimental economics: A critical reply to levitt and list. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1977749 (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Camerer, C. F., & Ho, T. H. (2015). Behavioral game theory experiments and modeling. Handbook of Game Theory with Economic Applications, 4(1), 517–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camerer, C. F., & Hogarth, R. M. (1999). The effects of financial incentives in experiments: A review and capital-labor-production framework. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 19, 7–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, D. T., & Stanley, J. C. (2015). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for research. Ravenio Books. [Google Scholar]

- Cappelen, A. W., Nygaard, K., Sørensen, E. Ø., & Tungodden, B. (2015). Social preferences in the lab: A comparison of students and a representative population. The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 117(4), 1306–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charness, G., & Gneezy, U. (2012). Strong evidence for gender differences in risk taking. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 83(1), 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charness, G., Gneezy, U., & Imas, A. (2013). Experimental methods: Eliciting risk preferences. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 87, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croson, R. (2005). The method of experimental economics. International Negotiation, 10(1), 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croson, R., & Gneezy, U. (2009). Gender differences in preferences. Journal of Economic Literature, 47(2), 448–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deck, C., & Schlesinger, H. (2014). Consistency of higher order risk preferences. American Economic Review, 104(9), 2694–2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deckers, T., Falk, A., Kosse, F., & Schildberg-Hrisch, H. (2015). How does socio-economic status shape a child’s personality? Available online: https://www.iza.org/publications/dp/8977/how-does-socio-economic-status-shape-a-childs-personality (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Dipartimento, E., & Marchetti, S. (2019). An experiment on coordination in a modified stag hunt game. University of Pisa. Available online: https://www.ec.unipi.it/documents/Ricerca/papers/2019-246.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- Ebert, S., & Wiesen, D. (2011). Testing for prudence and skewness seeking. Management Science, 57(7), 1334–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckel, C. C., & Grossman, P. J. (2008). Men, women, and risk aversion: Experimental evidence. Handbook of Experimental Economics Results, 1, 1061–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eeckhoudt, L., & Schlesinger, H. (2006). Putting risk in its proper place. American Economic Review, 96(1), 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evgenia, N., & Neycheva, M. (2014). Strategic behavior and game theory. In Strategic business decisions in a risky and rapidly changing environment (pp. 102–145). Flat. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exadaktylos, F., Espín, A. M., & Brañas-Garza, P. (2013). Experimental subjects are not different. Scientific Reports, 3(1), 1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falk, A., & Heckman, J. J. (2009). Lab experiments are a major source of knowledge in the social sciences. Science, 326(5952), 535–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Field, A. (2024). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics. Sage Publications Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Fréchette, G. R., & Schotter, A. (Eds.). (2015). Handbook of experimental economic methodology. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gneezy, U., & Rustichini, A. (2000). Pay enough or don’t pay at all. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115(3), 791–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, W. H. (2012). Econometric analysis (Pearson International ed.). Pearson Education, Limited. Available online: https://books.google.com/books?id=-WFPYgEACAAJ (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- Hackman, J. R. (2009). Why teams don’t work. Interview by Diane Coutu. Harvard Business Review, 87(5), 98–105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Haering, A., Heinrich, T., & Mayrhofer, T. (2020). Exploring the consistency of higher order risk preferences. International Economic Review, 61(1), 283–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, G. W., & List, J. A. (2004). Field experiments. Journal of Economic Literature, 42(4), 1009–1055. Available online: https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/0022051043004577 (accessed on 26 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- Holt, C. A. (1999). Teaching economics with classroom experiments: A symposium. Southern Economic Journal, 65(3), 603–610. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Holt, C. A. (2005). Veconlab: Virtual economics laboratory. University of Virginia. Available online: https://veconlab.econ.virginia.edu/admin.html (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Holt, C. A. (2007). Markets, games, & strategic behavior. Pearson Addison Wesley Boston. Available online: http://library.mpib-berlin.mpg.de/toc/z2007_1050.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Holt, C. A., & Laury, S. K. (2002). Risk aversion and incentive effects. American Economic Review, 92(5), 1644–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keren, G. B., & Raaijmakers, J. G. (1988). On between-subjects versus within-subjects comparisons in testing utility theory. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 41(2), 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimball, M. S. (1990). Precautionary saving in the small and the large. Econometrica, 58(1), 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneeland, T. (2015). Identifying higher-order rationality. Econometrica, 83(5), 2065–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, D. K., & Zheng, J. (2015). The relationship between economic theory and experiments. In Handbook of experimental economic methodology. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- List, J. A. (2007). Field experiments: A bridge between lab and naturally occurring data. The BE Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, 6(2), 0000102202153806371747. [Google Scholar]

- Nagel, R. (1995). Unraveling in guessing games: An experimental study. The American Economic Review, 85(5), 1313–1326. [Google Scholar]

- Natasha, R., & Soenarno, Y. N. (2018). The influence of prudence, cognitive ability, and personality on risk aversion. Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Science, 6(1), 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noussair, C. N., Trautmann, S. T., & van de Kuilen, G. (2014). Higher order risk attitudes, demographics, and financial decisions. The Review of Economic Studies, 81(1), 325–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prusak, L. (2011). Building a collaborative enterprise. Harvard Business Review, 89(7–8), 94–101. [Google Scholar]

- Skyrms, B. (2004). The stag hunt and the evolution of social structure. Cambridge University Press. Available online: https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=JykQZ9-wkcAC&oi=fnd&pg=PR11&dq=Skyrms,+B.+(2004).+The+stag+hunt+and+the+evolution+of+social+structure.+England:+Cambridge+University+Press (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Ye, M., Zheng, J., Nikolov, P., & Asher, S. (2020). One step at a time: Does gradualism build coordination? Management Science, 66(1), 113–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Guessing Game (Average Guess/StD) | Prudence Measurement Task (Avg. % Prudent Choices) | Risk Aversion Measurement Task (Avg. # Safe Choices/StD) | Stag Hunt Game (% Playing Pareto Optimal Action/StD) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range of responses | [0, 100] | [0, 1] | [0, 10] | [0, 1] | |

| Miami | All Miami | 36.30 (25.58) | 55% | 5.48 (2.10) | 0.71 (0.46) |

| Male | 35.64 (25.73) | 55% | 5.36 (1.92) | 0.77 (0.43) | |

| Female | 36.74 (25.86) | 56% | 5.56 (2.23) | 0.68 (0.48) | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 29.83 (22.20) | 60% | 5.57 (2.48) | 0.74 (0.44) | |

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 47.10 (27.67) | 48% | 5.33 (1.28) | 0.67 (0.48) | |

| Tucson | All Tucson | 31.98 (21.42) | 52% | 5.55 (1.47) | 0.84 (0.37) |

| Male | 28.04 (17.54) | 44% | 6.00 (1.47) | 0.78 (0.42) | |

| Female | 35.42 (24.06) | 58% | 5.16 (1.37) | 0.90 (0.30) | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 29.08 (20.63) | 54% | 5.85 (1.14) | 0.92 (0.28) | |

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 32.82 (21.80) | 51% | 5.47 (1.55) | 0.82 (0.39) | |

| Guessing Game | Prudence Task | Risk-Aversion Task | Stag-Hunt Game | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location (Miami = 1) | 8.561 † | −0.010 | −0.164 | −0.997 † |

| (4.744) | (0.414) | (0.371) | (0.517) | |

| Gender (Female = 1) | −4.281 | −0.315 | 0.340 | −0.120 |

| (4.379) | (0.382) | (0.343) | (0.466) | |

| Ethnicity (Minority = 1) | −11.355 | 0.335 | 0.297 | 0.517 |

| ** (4.791) | (0.420) | (0.375) | (0.513) | |

| Constant | 36.521 | 0.141 | 5.327 | 1.651 |

| *** (3.803) | (0.414) | *** (0.298) | *** (0.436) | |

| R2 | 0.065 | 0.014 | 0.015 | 0.034 |

| Observations | 114 | 114 | 114 | 114 |

| Variables | Mean Value | Mean Difference | t-Value | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Miami | Tucson | ||||

| All | 36.30 | 31.98 | 4.32 | 0.979 | 0.330 |

| Male | 35.64 | 28.04 | 7.60 | 1.226 | 0.226 |

| Female | 36.74 | 35.42 | 1.32 | 0.212 | 0.833 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 29.83 | 29.08 | 0.75 | 0.106 | 0.916 |

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 47.10 | 32.82 | 14.27 | 2.270 | 0.027 * |

| Variables | Mean Value | Mean Difference | t-Value | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Miami | Tucson | ||||

| All | 0.55 | 0.52 | 0.04 | 0.386 | 0.701 |

| Male | 0.55 | 0.44 | 0.10 | 0.693 | 0.492 |

| Female | 0.56 | 0.58 | −0.02 | −0.175 | 0.862 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 0.60 | 0.54 | 0.06 | 0.377 | 0.708 |

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 0.48 | 0.51 | −0.03 | −0.260 | 0.795 |

| Variables | Mean Value | Mean Difference | t-Value | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Miami | Tucson | ||||

| All | 5.48 | 5.55 | −0.07 | −0.206 | 0.837 |

| Male | 5.36 | 6.00 | −0.64 | −1.317 | 0.194 |

| Female | 5.56 | 5.16 | 0.40 | 0.856 | 0.396 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 5.57 | 5.85 | −0.27 | −0.383 | 0.703 |

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 5.33 | 5.47 | −0.13 | −0.344 | 0.732 |

| Variables | Mean Value | Mean Difference | t-Value | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Miami | Tucson | ||||

| All | 0.71 | 0.84 | −0.13 | −1.690 | 0.093 * |

| Male | 0.77 | 0.78 | −0.01 | −0.041 | 0.967 |

| Female | 0.68 | 0.90 | −0.23 | −2.275 | 0.026 ** |

| Hispanic/Latino | 0.74 | 0.92 | −0.18 | −1.364 | 0.179 |

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 0.67 | 0.82 | −0.16 | −1.404 | 0.165 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zumaeta, J.N. Economic Attitudes and Financial Decisions Among Welfare Recipients: Considerations for Workforce Policy. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 407. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18080407

Zumaeta JN. Economic Attitudes and Financial Decisions Among Welfare Recipients: Considerations for Workforce Policy. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(8):407. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18080407

Chicago/Turabian StyleZumaeta, Jorge N. 2025. "Economic Attitudes and Financial Decisions Among Welfare Recipients: Considerations for Workforce Policy" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 8: 407. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18080407

APA StyleZumaeta, J. N. (2025). Economic Attitudes and Financial Decisions Among Welfare Recipients: Considerations for Workforce Policy. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(8), 407. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18080407