The General Equilibrium Effects of Fiscal Policy with Government Debt Maturity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Model Specification

2.1. Households

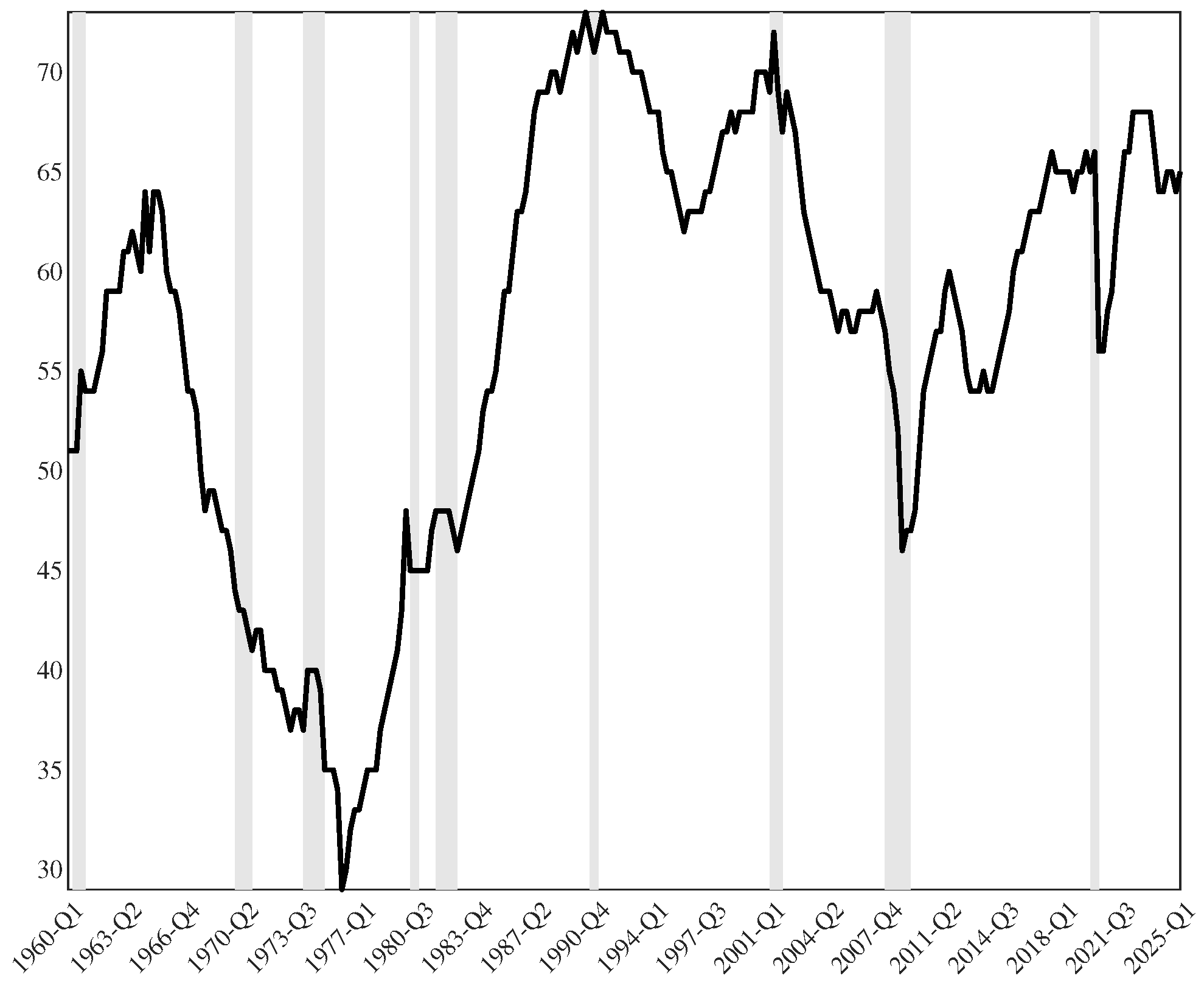

Government Debt Maturity Structure

2.2. The Labor Market

2.3. Production

2.3.1. Final Good Firm

2.3.2. Intermediate Firms

2.4. Fiscal Policy

2.5. Monetary Policy

Market Clearing and Aggregation

3. Calibration

4. Simulation Results

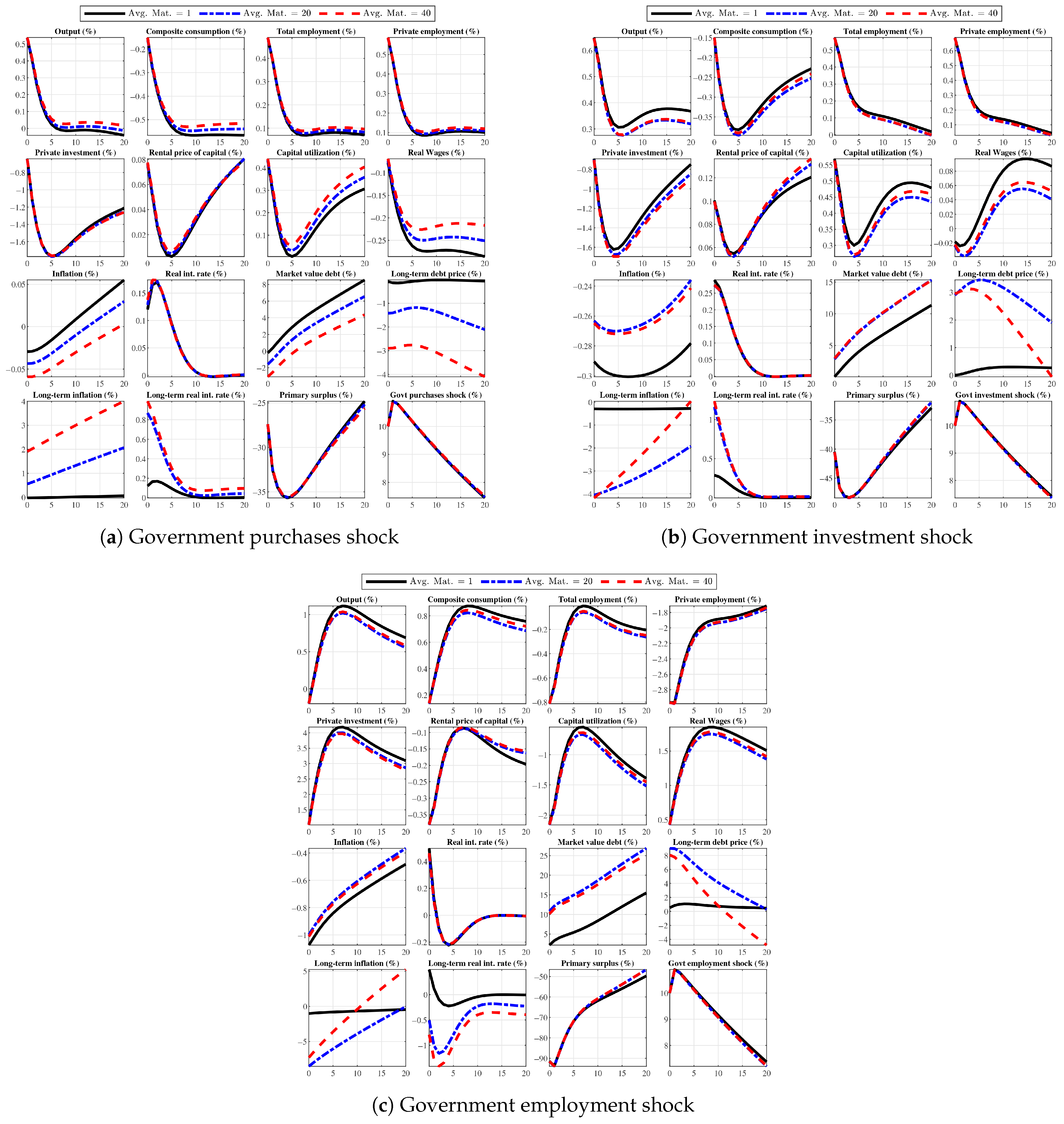

4.1. Government Spending Shocks

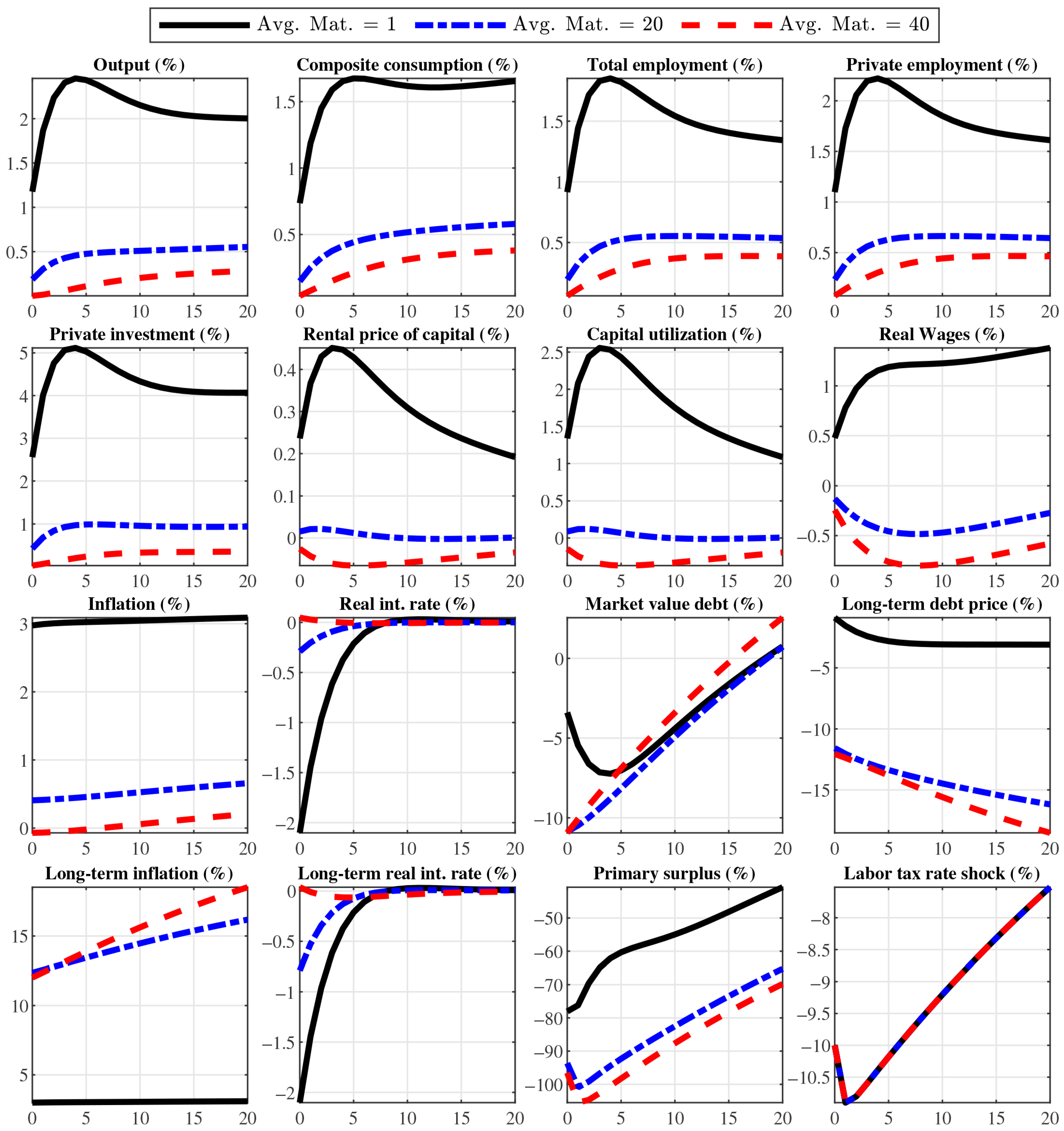

4.2. Shocks to Tax Rates

4.3. Fiscal Multipliers

4.4. Transmission Mechanism in an Alternative Policy Regime

5. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| 1 | Following H. Kim et al. (2023), we mainly focus on how the stance of monetary policy conditions the effects of expansionary fiscal policy, considering two regimes: (1) a dovish monetary policy that is well-coordinated with expansionary fiscal policy (Regime D), and (2) a hawkish monetary policy that conflicts with expansionary fiscal policy (Regime H). |

| 2 | Another strand of the literature on government debt maturity focuses on modeling optimal debt maturity and also highlights how the composition of government debt affects the degree of fiscal financing through the debt valuation channel (see Angeletos, 2002; Berndt et al., 2012; Greenwood et al., 2015). |

| 3 | Here we use the end of period stock timing convention. That is, variables are assigned the timing at which they are determined. For example, the capital stock k used at time t in the production function for is determined by investment at time . |

| 4 | As illustrated by L. J. Christiano et al. (2010), allowing for the variable capital utilization is a way to make the services of capital elastic. In any model, prices are heavily influenced by costs. Costs in turn are influenced by the elasticity of the factors of production. If there is very little curvature in the cost function , then households are able to expand capital services without much increase in cost. So inflation will not rise much in response to monetary policy. |

| 5 | We need this condition to linearize the model presented here. |

| 6 | Gomes (2010) and Quadrini and Trigari (2007) suggest that government wages should keep track of the private sector wages over the business cycle which helps reduce unemployment volatility. |

| 7 | That is, if a firm changes its price, it must pay a price adjustment cost with nominal output serving as the cost base. A common example of price adjustment costs is menu costs. |

| 8 | Following Leeper et al. (2017), we do not allow consumption taxes to respond to debt. Consumption taxes consist of excise taxes and custom duties, which average 1 percent of GDP in the US federal government data. |

| 9 | The sample stops in 2019 in order for our results not to be biased from the COVID-19 period. |

References

- Ambler, S., & Paquet, A. (1996). Fiscal spending shocks, endogenous government spending, and real business cycles. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 20(1–3), 237–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeletos, G.-M. (2002). Fiscal policy with noncontingent debt and the optimal maturity structure. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(3), 1105–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermperoglou, D., Pappa, E., & Vella, E. (2017). The government wage bill and private activity. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 79, 21–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernanke, B. S., & Mihov, I. (1998). Measuring monetary policy. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 113(3), 869–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berndt, A., Lustig, H., & Yeltekin, Ş. (2012). How does the US government finance fiscal shocks? American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 4(1), 69–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bilbiie, F. O. (2011). Nonseparable preferences, frisch labor supply, and the consumption multiplier of government spending: One solution to a fiscal policy puzzle. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 43(1), 221–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, O., & Perotti, R. (2002). An empirical characterization of the dynamic effects of changes in government spending and taxes on output. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(4), 1329–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehm, C. E. (2020). Government consumption and investment: Does the composition of purchases affect the multiplier? Journal of Monetary Economics, 115, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldrin, M., Christiano, L. J., & Fisher, J. D. M. (2001). Habit persistence, asset returns, and the business cycle. American Economic Review, 91(1), 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouakez, H., & Rebei, N. (2007). Why does private consumption rise after a government spending shock? Canadian Journal of Economics, 40(3), 954–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broner, F., Clancy, D., Erce, A., & Martin, A. (2022). Fiscal multipliers and foreign holdings of public debt. The Review of Economic Studies, 89(3), 1155–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnside, C., Eichenbaum, M., & Fisher, J. D. (2004). Fiscal shocks and their consequences. Journal of Economic Theory, 115(1), 89–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiano, L., Eichenbaum, M., & Rebelo, S. (2011). When is the government spending multiplier large? Journal of Political Economy, 119(1), 78–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiano, L. J., & Eichenbaum, M. (1992). Current real-business-cycle theories and aggregate labor-market fluctuations. American Economic Review, 82(3), 430–450. [Google Scholar]

- Christiano, L. J., Eichenbaum, M., & Evans, C. L. (2005). Nominal rigidities and the dynamic effects of a shock to monetary policy. Journal of Political Economy, 113(1), 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiano, L. J., Trabandt, M., & Walentin, K. (2010). DSGE models for monetary policy analysis. In Handbook of monetary economics (Vol. 3, pp. 285–367). [Google Scholar]

- Clarida, R., Gali, J., & Gertler, M. (2000). Monetary policy rules and macroeconomic stability: Evidence and some theory. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115(1), 147–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochrane, J. H. (2001). Long-term debt and optimal policy in the fiscal theory of the price level. Econometrica, 69(1), 69–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coenen, G., Erceg, C. J., Freedman, C., Furceri, D., Kumhof, M., Lalonde, R., Laxton, D., Lindé, J., Mourougane, A., Muir, D., Mursula, S., de Resende, C., Roberts, J., Roeger, W., Snudden, S., Trabandt, M., & in’t Veld, J. (2012). Effects of fiscal stimulus in structural models. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 4(1), 22–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsetti, G., Meier, A., & Müller, G. J. (2012). Fiscal stimulus with spending reversals. Review of Economics and Statistics, 94(4), 878–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, J., & Schuh, S. (2021). Is the taylor rule still an adequate representation of monetary policy in macroeconomic models? West Virginia University, College of Business and Economics. [Google Scholar]

- De Graeve, F., & Mazzolini, G. (2023). The maturity composition of government debt: A comprehensive database. European Economic Review, 154, 104438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, A. K., & Stiglitz, J. E. (1977). Monopolistic competition and optimum product diversity. American Economic Review, 67(3), 297–308. [Google Scholar]

- Edelberg, W., Eichenbaum, M., & Fisher, J. D. (1999). Understanding the effects of a shock to government purchases. Review of Economic Dynamics, 2(1), 166–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatás, A., & Mihov, I. (2001). The effects of fiscal policy on consumption and employment: Theory and evidence (Tech. Rep.). CEPR Discussion Papers 2760. Centre for Economic Policy Research. [Google Scholar]

- Finn, M. G. (1998). Cyclical effects of government’s employment and goods purchases. International Economic Review, 39(3), 635–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galí, J., López-Salido, J. D., & Vallés, J. (2007). Understanding the effects of government spending on consumption. Journal of the European Economic Association, 5(1), 227–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghomi, M., Mankart, J., Oikonomou, R., & Priftis, R. (2025). Fiscal multipliers and the maturity financing of government spending shocks. Available online: https://mankart.net/research2/Fiscal%20Multipliers%20and%20Maturity%20GMOP.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Gomes, P. M. (2010). Fiscal policy and the labour market: The effects of public sector employment and wages (Tech. Rep.). IZA Discussion Paper 5321. Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA). [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood, R., Hanson, S. G., & Stein, J. C. (2015). A comparative-advantage approach to government debt maturity. The Journal of Finance, 70(4), 1683–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ireland, P. N. (1997). A small, structural, quarterly model for monetary policy evaluation. Carnegie Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy, 47(1). [Google Scholar]

- Jo, Y. J., & Zubairy, S. (2025). State-dependent government spending multipliers: Downward nominal wage rigidity and sources of business cycle fluctuations. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 17(1), 379–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judd, J. P., & Rudebusch, G. D. (1998). Taylor’s rule and the fed: 1970–1997. Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Economic Review, 3, 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Karras, G. (1994). Government spending and private consumption: Some international evidence. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 26(1), 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H., Shao, P., & Zhang, S. (2023). Policy coordination and the effectiveness of fiscal stimulus. Journal of Macroeconomics, 75, 103489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. (2000). Constructing and estimating a realistic optimizing model of monetary policy. Journal of Monetary Economics, 45(2), 329–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeper, E. M., & Leith, C. (2016). Chapter 30—Understanding inflation as a joint monetary–fiscal phenomenon. In J. B. Taylor, & H. Uhlig (Eds.), Handbook of macroeconomics (Vol. 2, pp. 2305–2415). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Leeper, E. M., Traum, N., & Walker, T. B. (2017). Clearing up the fiscal multiplier morass. American Economic Review, 107(8), 2409–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnemann, L. (2009). Macroeconomic effects of shocks to public employment. Journal of Macroeconomics, 31(2), 252–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macauley, F. R. (1938). The movement of interest rates, bond yields and stock prices in the united states since 1856. National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolsko-Rzhevskyy, A., Papell, D. H., & Prodan, R. (2014). Deviations from rules-based policy and their effects. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 49, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappa, E. (2009). The effects of fiscal shocks on employment and the real wage. International Economic Review, 50(1), 217–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quadrini, V., & Trigari, A. (2007). Public employment and the business cycle. The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 109(4), 723–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramey, V. A. (2012). Government spending and private activity. In Fiscal policy after the financial crisis (Vol. 1, pp. 19–55). National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Rannenberg, A. (2021). State-dependent fiscal multipliers with preferences over safe assets. Journal of Monetary Economics, 117, 1023–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotemberg, J. J. (1982). Sticky prices in the United States. Journal of Political Economy, 90(6), 1187–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sbordone, A. M., Tambalotti, A., Rao, K., & Walsh, K. J. (2010). Policy analysis using DSGE models: An introduction. FRBNY Economic Policy Review, 16(2), 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, C. A. (2002). Solving linear rational expectations models. Computational Economics, 20(1–2), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, C. A. (2013). Paper money. American Economic Review, 103(2), 563–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smets, F., & Wouters, R. (2007). Shocks and frictions in US business cycles: A Bayesian DSGE approach. American Economic Review, 97(3), 586–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodford, M. (2001). Fiscal requirements for price stability. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 33(3), 669–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodford, M. (2011). Simple analytics of the government expenditure multiplier. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 3(1), 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynne, M. (1992). The analysis of fiscal policy in neoclassical models (Tech. Rep.). Working Paper 9212. Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. [Google Scholar]

- Zubairy, S. (2014). On fiscal multipliers: Estimates from a medium scale DSGE model. International Economic Review, 55(1), 169–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter Description | Values |

|---|---|

| Preference and HHs | |

| , discount factor | 0.99 |

| h, habit formation | 0.9 |

| , inverse Frisch labor elasticity | 2 |

| , capital depreciation rate | 0.025 |

| , subs. of private/public cons. | −0.25 |

| , steady-state capital ratio | 0.34 |

| , steady-state employment ratio | 5.02 |

| Frictions and Production | |

| , productivity of private capital | 0.33 |

| , productivity of govt employment | 0.25 |

| , productivity of govt capital | 0.1 |

| , price/wage elasticity of demand | 6 |

| , Calvo pricing | 0.85 |

| , price/wage adjustment cost. | |

| , capital utilization | 0.15 |

| , investment adjustment cost | 5 |

| Monetary/Fiscal Calibrations | |

| , steady-state govt purchases-to-GDP ratio | 0.052 |

| , steady-state govt investment-to-GDP ratio | 0.074 |

| , lagged resp. for fiscal instruments | 0.98 |

| , steady-state market value debt-to-GDP ratio | 1.501 |

| , steady-state consumption tax rate | 0.023 |

| , steady-state labor tax rate | 0.217 |

| , steady-state capital tax rate | 0.250 |

| Regime D (benchmark) | |

| Monetary Policy | |

| , interest rate resp. to inflation | 0.83 |

| , interest rate resp. to output | 0.27 |

| , resp. to lagged interest rate | 0.68 |

| Fiscal Policy | |

| , fiscal instruments resp. to debt | 0 |

| Regime H | |

| Monetary Policy | |

| , interest rate resp. to inflation | 2.15 |

| , interest rate resp. to output | 0.93 |

| , resp. to lagged interest rate | 0.79 |

| Fiscal Policy | |

| , fiscal instruments resp. to debt | 0.05 |

| Avg. Maturity | 1 | 20 | 40 | 1 | 20 | 40 | 1 | 20 | 40 | 1 | 20 | 40 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time Horizons | Output Multiplier | Consumption Multiplier | Investment Multiplier | Employment Multiplier | |||||||||||

| Increase in | Impact | 2.06 | 1.35 | 1.24 | 0.48 | 0.18 | 0.13 | 0.14 | −0.09 | −0.12 | 1.02 | 0.71 | 0.66 | ||

| 10 qtrs | 2.03 | 0.83 | 0.65 | 0.47 | −0.06 | −0.14 | 0.06 | −0.30 | −0.35 | 0.91 | 0.44 | 0.37 | |||

| 20 qtrs | 1.91 | 0.69 | 0.51 | 0.41 | −0.17 | −0.25 | 0.01 | −0.35 | −0.41 | 0.83 | 0.37 | 0.30 | |||

| 40 qtrs | 2.02 | 0.67 | 0.47 | 0.43 | −0.25 | −0.35 | 0.05 | −0.37 | −0.43 | 0.84 | 0.37 | 0.30 | |||

| Impact | 0.39 | −0.44 | −0.65 | 0.40 | 0.05 | −0.04 | 0.28 | 0.02 | −0.05 | −1.23 | −1.59 | −1.69 | |||

| 10 qtrs | 1.78 | 0.06 | −0.34 | 1.09 | 0.30 | 0.12 | 0.59 | 0.10 | −0.02 | −0.78 | −1.44 | −1.60 | |||

| 20 qtrs | 1.95 | 0.31 | −0.11 | 1.26 | 0.46 | 0.26 | 0.59 | 0.11 | −0.01 | −0.76 | −1.36 | −1.51 | |||

| 40 qtrs | 2.30 | 0.57 | 0.13 | 1.54 | 0.64 | 0.41 | 0.66 | 0.14 | 0.01 | −0.67 | −1.28 | −1.43 | |||

| Impact | 1.73 | 0.94 | 0.76 | 0.24 | −0.09 | −0.17 | 0.11 | −0.14 | −0.20 | 0.84 | 0.50 | 0.42 | |||

| 10 qtrs | 1.78 | 0.48 | 0.21 | 0.36 | −0.24 | −0.37 | −0.01 | −0.37 | −0.45 | 0.68 | 0.20 | 0.10 | |||

| 20 qtrs | 1.73 | 0.40 | 0.11 | 0.38 | −0.26 | −0.40 | −0.08 | −0.45 | −0.53 | 0.57 | 0.11 | 0.01 | |||

| 40 qtrs | 1.93 | 0.46 | 0.13 | 0.51 | −0.25 | −0.42 | −0.06 | −0.49 | −0.59 | 0.54 | 0.04 | −0.06 | |||

| Reduction of | Impact | 0.94 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.42 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.30 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.44 | 0.08 | 0.02 | ||

| 10 qtrs | 2.29 | 0.30 | 0.06 | 1.15 | 0.20 | 0.08 | 0.69 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 1.03 | 0.20 | 0.09 | |||

| 20 qtrs | 2.38 | 0.36 | 0.12 | 1.27 | 0.26 | 0.13 | 0.71 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 1.03 | 0.23 | 0.13 | |||

| 40 qtrs | 2.87 | 0.48 | 0.20 | 1.64 | 0.35 | 0.20 | 0.86 | 0.13 | 0.04 | 1.18 | 0.28 | 0.17 | |||

| Impact | 1.42 | 0.49 | 0.29 | 0.27 | −0.09 | −0.17 | 0.22 | −0.05 | −0.11 | −0.05 | −0.40 | −0.48 | |||

| 10 qtrs | 2.17 | 0.38 | 0.06 | 0.56 | −0.17 | −0.30 | 0.46 | −0.06 | −0.16 | 0.16 | −0.44 | −0.55 | |||

| 20 qtrs | 2.32 | 0.45 | 0.11 | 0.63 | −0.16 | −0.30 | 0.53 | −0.02 | −0.12 | 0.17 | −0.41 | −0.52 | |||

| 40 qtrs | 2.77 | 0.62 | 0.23 | 0.87 | −0.11 | −0.28 | 0.69 | 0.05 | −0.07 | 0.27 | −0.36 | −0.48 | |||

| Impact | 0.88 | 0.19 | 0.08 | 0.41 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.25 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.40 | 0.09 | 0.05 | |||

| 10 qtrs | 1.63 | 0.38 | 0.19 | 0.90 | 0.33 | 0.24 | 0.34 | −0.03 | −0.09 | 0.69 | 0.19 | 0.11 | |||

| 20 qtrs | 1.68 | 0.42 | 0.22 | 1.02 | 0.42 | 0.32 | 0.27 | −0.10 | −0.16 | 0.69 | 0.21 | 0.14 | |||

| 40 qtrs | 1.87 | 0.49 | 0.27 | 1.20 | 0.49 | 0.37 | 0.26 | −0.16 | −0.23 | 0.74 | 0.25 | 0.17 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, S.; Lin, Z. The General Equilibrium Effects of Fiscal Policy with Government Debt Maturity. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 396. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18070396

Zhang S, Lin Z. The General Equilibrium Effects of Fiscal Policy with Government Debt Maturity. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(7):396. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18070396

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Shuwei, and Zhilu Lin. 2025. "The General Equilibrium Effects of Fiscal Policy with Government Debt Maturity" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 7: 396. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18070396

APA StyleZhang, S., & Lin, Z. (2025). The General Equilibrium Effects of Fiscal Policy with Government Debt Maturity. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(7), 396. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18070396