Abstract

This study examines the impact of financial inclusion (FI) on reducing poverty and income inequality in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), using panel data from 15 countries for the period 2004–2021. System GMM with robust errors was used to address endogeneity issues, and FI was assessed in terms of access to and use of the financial system. The results indicate that increased FI contributes to reducing poverty and income inequality in LAC. While access to financial services plays a crucial role in poverty reduction, the utilization of financial services has a more profound impact on combating income inequality. These results underscore the importance of policies designed to improve financial access and promote the use of financial products and services. It is recommended to expand the banking infrastructure, facilitate the provision of low-cost accounts, and strengthen financial education programs.

1. Introduction

Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) continue to face persistent challenges related to poverty and inequality. According to recent estimates, nearly 29% of the population lives below the poverty line and 11% lives in extreme poverty (Rodríguez et al., 2024), while the wealthiest 10% earn an average of 12 times more than the poorest 10% (Bachelet, 2024). These indicators reflect structural problems that not only limit individual well-being but also hinder the region’s economic and social development (ECLAC, 2025; Sawadogo & Semedo, 2021).

A critical, though not always visible, dimension of this inequality is financial exclusion. In 2021, 41% of adults in LAC lacked access to formal financial services, a figure considerably higher than in regions such as East Asia (Global Findex, 2021). This exclusion particularly impacts women, people with low education, informal workers, and rural populations (Demirgüç-Kunt et al., 2022; Zins & Weill, 2016; Quispe Mamani et al., 2024; Cassimon et al., 2022; Orazi et al., 2023). Lack of access to bank accounts, credit, or insurance restricts households’ ability to save, cope with emergencies, or invest in productive activities (Sarma & Pais, 2011), thus perpetuating cycles of poverty and vulnerability. This situation is exacerbated in an environment characterized by high costs and low efficiency of the financial system (Rojas-Suárez, 2016; Zmerli & Castillo, 2015), where high interest rates, commissions, and opaque conditions hinder the effective use of financial services. In many cases, these costs discourage the sustained use of products, especially among the most vulnerable sectors, and can negate the expected benefits of financial inclusion (Pietrovito & Pozzolo, 2021).

However, over the past two decades, LAC has implemented public policies that have promoted banking access through conditional cash transfers, social programs, and digital strategies. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, Brazil opened more than 25 million digital accounts in two weeks to distribute aid to the unbanked population (Fonseca & Matray, 2024; World Bank Group, 2024). These types of initiatives demonstrate how social policies can serve as channels for passive financial inclusion, facilitating broader integration into the financial system (Demirgüç-Kunt et al., 2018).

As countries expand financial coverage, it becomes critical to distinguish between two key dimensions of financial inclusion (FI): access to and active use of financial services. Access refers to the availability of basic financial accounts or products. At the same time, use involves the effective integration of these services into everyday economic life, such as frequent use of savings, digital payments, or sustained access to credit (Mohd Daud et al., 2024; Kling et al., 2022; Barra et al., 2024).

To analyze the effect of financial inclusion on poverty and income inequality in Latin America and the Caribbean, a dynamic panel data model was applied to 15 countries over the period 2004–2021. Given the risk of endogeneity arising from the possible reverse causality between financial inclusion and poverty/inequality, the model was estimated using the two-stage System GMM method with robust errors, proposed by Arellano and Bover (1995) and Blundell and Bond (1998). This technique enables simultaneous control for unobservable fixed effects, time dynamics, and endogenous variables through the use of internal instruments (lags). Additionally, relevant macroeconomic indicators, including GDP growth, inflation, secondary school enrollment, and private credit, were also included. The validity of the model was checked using the Hansen and Arellano–Bond tests. Unlike much of the literature, which focuses solely on access, this research breaks down the financial inclusion indicator into two components: access and use, assessing their distinct effects on poverty and inequality.

Analyzing these phenomena separately is key, since poverty and inequality capture distinct dimensions of well-being. Poverty refers to absolute deprivation, while inequality describes the distribution of income among the population. It is possible to have low poverty with high inequality, or vice versa (Piketty & Sáez, 2014), which requires differentiated policies. Therefore, the study allows us to identify which dimension of financial inclusion is most effective in reducing poverty or closing distributional gaps.

The results indicate that financial inclusion has a significant impact on poverty and inequality, with notable differences: financial access primarily reduces poverty, while the active use of financial services has a greater effect on income inequality in LAC. These findings remain consistent after controlling for variables such as annual GDP growth, inflation, and private sector credit.

The policy implications of these results are that expanding financial access is essential to combating poverty, but reducing inequality requires encouraging the effective use of financial services. This entails promoting tailored financial products, driving financial digitalization, improving financial education, reducing user costs, and avoiding regressive financial practices. This is especially true for traditionally excluded groups such as women, rural populations, and informal workers. This will enable improved efficiency in the financial system.

This study contributes to the literature on several fronts: (1) it uses a multidimensional index of financial inclusion constructed by the IMF (Svirydzenka, 2016), which is more robust than simple account holding indicators; (2) it addresses an empirical gap by analyzing the effects of financial access and use on poverty and inequality in a differentiated way; (3) it focuses specifically on LAC, a region with high levels of exclusion and scarce disaggregated regional evidence; and (4) it contributes to the still open debate on the relationship between financial inclusion and inequality, where the results of the international literature remain mixed; (5) it empirically adopts a macroeconomic and regional approach, unlike much of the FI literature that has focused on microeconomic analyses based on households or individuals (individual surveys).

The research is divided into the following sections: the next section reviews the literature, followed by a description of the methodological aspects of the developed model, and finally, the presentation of the results and conclusions of the work.

2. IF Context in Latin America

Since the beginning of the 21st century, and with increasing intensity since 2010, Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) have experienced significant growth in financial access, particularly among low-income populations. This process cannot be understood without recognizing the central role played by public policies, particularly conditional cash transfers (CCTs) and social programs that incorporated financial mechanisms as a channel for distributing state resources. Emblematic initiatives such as Bolsa Família (Brazil), Prospera (Mexico), Familias en Acción (Colombia), or Juntos (Peru) used simplified bank accounts for the delivery of aid, causing an increase in formal banking access (Magalhães et al., 2024; Nazareno & de Castro Galvao, 2023). However, this access occurred instrumentally, as a means to receive public income, rather than through spontaneous demand or full financial inclusion. Continuously, the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated this process by forcing governments to channel emergency aid through digital platforms. Programs such as Ingreso Solidario (Colombia), Bono Familiar Universal (Peru), Bono de Protección Familiar (Ecuador), among others, expanded the scope of digital financial inclusion, although they also revealed persistent structural limitations: digital divide, low financial literacy and distrust towards formal institutions (Antwi et al., 2024; World Bank, 2021). In this context, it is crucial to distinguish between the direct redistributive impact of public policies and the potential long-term effects associated with the active use of financial services (Rojas-Suárez, 2016; Cámara & Tuesta, 2014; Beck et al., 2009). In many cases, the observed impact on poverty reduction is more a result of increased disposable income than of functional integration into the formal financial system. However, these policies lay the groundwork for greater exposure of the excluded population to the financial system, opening opportunities for more structured integration.

However, inclusion focused solely on access can hide regressive or extractive dimensions of the financial system in LAC (World Bank, 2021). One of the main structural obstacles is the high cost of financial services. (Rojas-Suárez, 2016; Zmerli & Castillo, 2015). This includes high commissions, exorbitant interest rates, maintenance and transaction fees, as well as barriers such as documentation requirements or lengthy transfer times, which particularly affect low-income households and micro-enterprises. For example, the intermediation margin in LAC exceeds 6% on average, more than double that of East Asia (International Monetary Fund, 2021). In countries such as Mexico, annual interest rates of three and even four digits have been documented in unregulated institutions, including SOFOMES, which have even exceeded 1000% in certain cases (Torres et al., 2017; Government of Mexico, 2012). Institutions such as Compartamos Banco have been heavily criticized for replicating logics of value extraction rather than effective inclusion (Bruck, 2006). These conditions can transform formal access into an additional financial burden, exacerbating over-indebtedness or eroding the disposable income of the most vulnerable households. In these cases, the financial system does not function as a facilitator of well-being, but rather as a regressive mechanism, which raises questions about its actual efficiency in terms of inclusion. This suggests that the expansion of access should be evaluated not only by its coverage, but also by the quality, affordability, and sustainability of the services offered (Demirgüç-Kunt et al., 2018). In fact, in 2021, 60% of unbanked people in LAC reported that they do not have an account in the financial system because they considered financial services too expensive (Global Findex, 2021). This situation reflects a financial inclusion that is conditioned by regressive dynamics, which could deepen inequality and exclusion if these inefficiencies in the financial market persist.

Additionally, financial inclusion in LAC presents a substantial degree of socioeconomic segmentation. Recent studies show that the groups most excluded from the formal system are: women, the rural population, people with low education, young people, and informal workers (Global Findex, 2021; Zins & Weill, 2016; Quispe Mamani et al., 2024; Cassimon et al., 2022; Orazi et al., 2023). Having a bank account is more common among men (60%) than among women (52%), and adults with lower educational levels are up to 50% less likely to access the financial system (Demirgüç-Kunt et al., 2022). Rural areas face physical barriers, higher transaction costs, and lower infrastructure coverage (Rojas-Suárez, 2016; Zmerli & Castillo, 2015), while informal workers are often excluded due to a lack of credit history or collateral (Pietrovito & Pozzolo, 2021). In contrast, urban sectors, characterized by higher educational levels and job stability, have a deeper and more diversified use of the system, ranging from credit cards to insurance and digital loans (Demirgüç-Kunt et al., 2022; Omar & Inaba, 2020). This structural asymmetry produces unequal inclusion, where the type of accessible financial product, its cost, and its final impact are strongly conditioned by the socioeconomic profile.

Despite the valuable contributions of microeconomic literature on financial inclusion, its limited focus on households or individuals prevents it from capturing long-term aggregate and structural effects (Jensen & Naveed, 2025). This research addresses this gap by analyzing, from a macroeconomic and cross-country perspective, the link between financial inclusion, poverty, and inequality in Latin America and the Caribbean. By incorporating aggregate indicators and broad time series, the study aims to identify regional patterns and systemic effects that complement microeconomic findings, providing valuable evidence for the design of more comprehensive public policies aimed at sustainable social development.

3. Theoretical Framework and Literature Review

3.1. Theoretical Approach: Financial Inclusion, Poverty, and Inequality

Financial inclusion, defined as the effective access of the population to financial services, has been recognized as a key mechanism for reducing poverty and inequality. The theoretical model that explains this relationship is the Greenwood and Jovanovic model (1990), which provides a relevant theoretical framework for understanding how financial development drives economic growth and affects income distribution. In this model, initial access to financial services is limited to particular groups, which can increase inequality in the early stages of development. However, as the financial system expands and more agents access services such as credit, savings, and insurance, inequality is reduced, and more equitable growth is promoted. Furthermore, endogenous growth models with financial frictions, such as those proposed by Galor and Zeira (1993) and Aghion and Bolton (1997), posit that restrictions on access to credit perpetuate poverty by limiting investment in human capital and productive activities.

Taken together, these approaches suggest that greater financial inclusion can positively reduce poverty and income inequality by expanding economic opportunities. Financial inclusion thus acts as a mechanism to overcome structural barriers, enabling better resource allocation and greater participation in the productive process.

3.2. Financial Inclusion and Poverty

From a microeconomic perspective, financial inclusion has been studied for its ability to improve household well-being and reduce poverty at the grassroots level. The most emblematic case is that of the Grameen Bank in Bangladesh, which, since the 1980s, has demonstrated that microcredit can empower low-income individuals and transform their economic situation (Yunus, 2008).

Despite these gaps, financial inclusion has established itself as a crucial component of economic development, directly contributing to poverty reduction. Access to basic financial services such as savings accounts, credit, insurance, and payment methods allows households to improve their investment capacity, plan for the long term, cope with unforeseen events, invest, and take advantage of economic opportunities that increase their well-being (Singer et al., 2017; Álvarez-Gamboa et al., 2021). Furthermore, it encourages domestic savings and local investment, which contributes to sustainable economic growth (Kumar, 2023). Additionally, Gupta and Kanung (2022) show that the access and depth (use) of these services favor access to formal financial services, boost entrepreneurship in rural areas, and improve the incomes of the poorest households, consolidating their role as a key tool against financial exclusion.

Other studies highlight the individual-level effects of FI on poverty. In Nigeria, Abubakar and Malumfashi (2022) show that access to financial services improves personal income and reduces poverty. In Peru, Schmied and Marr (2016) demonstrate that financial access has a positive impact on various poverty indicators, using household data. In Ecuador, Álvarez-Gamboa et al. (2021) highlight the effect on multidimensional poverty and underline the need to address territorial disparities.

Similarly, in the Asian context, Wang and Huang (2024) find that digital financial tools in China have significantly contributed to reducing multidimensional poverty. This measure typically focuses on household well-being. Tao et al. (2023) reinforce these findings by demonstrating that digital finance has been effective in reaching previously excluded sectors and easing credit constraints at the individual level, reflecting a demand-side approach to inclusion.

From a macroeconomic perspective, several studies have examined the relationship between financial inclusion and variables such as poverty and inequality at the country level. This literature uses panel models, aggregate indicators, and cross-country comparisons to assess whether the growth of financial inclusion has positive structural effects.

Regarding poverty, several studies confirm that financial inclusion and poverty reduction are key worldwide. Memon et al. (2025), using data from 132 countries between 2004 and 2019, show using instrumental variables that financial access facilitates the integration of marginalized populations into the formal economy. Aracil et al. (2022), analyzing 75 countries, show that this effect is stronger in countries with better institutional quality and lower incomes. Azmeh (2025) demonstrates that the development of inclusive digital finance in developing countries significantly reduces the likelihood of falling into relative poverty by overcoming the barriers of the traditional financial system. Jensen and Naveed (2025) show that the increase in microfinance (one form of financial inclusion) reduces inequality and poverty, especially among the poorest 20%, highlighting the redistributive potential of financial inclusion that targets vulnerable populations.

Saha and Qin (2023) analyze two types of poverty across 156 countries and conclude that financial inclusion has a significant impact on extreme poverty, particularly in developing countries. They also highlight that the effect is weak or null in high-income economies. This is consistent with Park and Mercado (2015), who show that its expansion does not guarantee additional poverty reduction once a minimum inclusion threshold is reached. Tabash et al. (2024) identify an optimal threshold of 42% financial inclusion, beyond which the marginal benefits of further inclusion disappear.

In Asia, Wong et al. (2023) employ autoregressive distributed lag models to conclude that financial inclusion has a significant impact in reducing poverty. In Indonesia, Erlando et al. (2020) apply VAR and PVAR models, confirming that the effect is greater on extreme poverty than on moderate poverty.

In Africa, attention has focused on digital financial inclusion as a mechanism to close structural gaps. Kumar (2023), in a long-term study (1970–2020) with data from 68 developing countries, concludes that financial inclusion has a substantial impact on poverty reduction, regardless of initial levels. In sub-Saharan Africa, Osuma (2025) highlights that digital financial services have expanded access to economic resources, with positive impacts on growth and poverty, as indicated by GMM and quantile regression models. Tabash et al. (2024), in their analysis of the development of African economies between 2004 and 2021, also find positive impacts using dynamic threshold models.

In Latin America, the related literature is scarcer. Polloni-Silva et al. (2021) show that technological adoption in financial services reduces the poverty rate in 13 countries. This research aims to contribute to this line of inquiry by providing macroeconomic evidence specific to Latin America, distinguishing the effects of access, use, and efficiency of financial services.

3.3. Financial Inclusion and Inequality

The literature analyzing the relationship between financial inclusion and inequality is controversial. While several studies support the potential of financial inclusion to reduce disparities, others indicate that its effects may be limited, driven by structural factors, or even regressive in specific contexts. The literature analyzing this relationship is more limited for Latin American and Caribbean countries than for other regions.

From a microeconomic perspective, the evidence suggests that the effects of financial inclusion on inequality can be substantial. However, they are highly contingent upon structural factors and the design of policies.

In Latin American and Caribbean countries, where the literature remains limited, Omar and Inaba (2020) find that equitable access to financial services reduces inequality, particularly when targeting marginalized groups, such as women. Similarly, Polloni-Silva et al. (2021) show that in 13 Latin American countries, the combination of financial inclusion and technological inclusion (such as mobile phone use) amplifies the positive effects on equity.

In Asia, Wong et al. (2023) caution that financial inclusion can exacerbate inequality when accompanied by digital innovation, due to the technological barriers faced by the poorest sectors. This finding is supported by Suhrab et al. (2024), who demonstrate how urban–rural gaps and unequal internet access exacerbate existing inequalities. In China, Kling et al. (2022) argue that rapid financial growth without adequate regulation can expose low-income households to disproportionate risks, generating adverse effects.

These studies demonstrate that heterogeneity in access, digital capabilities, and the regulatory context significantly influences the actual impact of financial inclusion on the most vulnerable sectors. Therefore, it is crucial to adopt a segmented approach sensitive to socioeconomic profiles, rather than assuming homogeneous aggregate impacts.

From a macroeconomic perspective, the relationship between financial inclusion and inequality remains a subject of controversy. Barra et al. (2024), using a sample of 57 countries, find that the benefits of financial inclusion are greater in countries with high initial inequality. Mbona (2022), using a generalized moments model for 120 countries, concludes that the distributional benefits of financial inclusion are nonlinear and depend on certain thresholds. Conversely, de la Cuesta-González et al. (2020) warn of regressive effects when there is excess financing, as observed in OECD countries before and after financial crises.

In Africa, studies also confirm significant country-level effects. Tabash et al. (2024) find that in African countries with recent conflicts, financial inclusion helps reduce inequality and stimulate trade. Kebede et al. (2023) show that this impact is stronger in countries with high levels of inequality, provided a strong institutional framework is in place. Girma and Huseynov (2023) find a causal relationship across 29 African countries between access to accounts and credit and reductions in inequality. Adeleke and Olomola (2022) confirm these positive long-run effects using VAR models in Nigeria. In contrast, Bolarinwa and Akinlo (2021) identify a U-shaped relationship: the benefits diminish or even reverse if financial inclusion does not target the most vulnerable. Sawadogo and Semedo (2021) reinforce this idea, showing that the benefits only materialize with strong institutional frameworks. In Asia, Pham and Luu (2024) find that financial inclusion reduces national-level inequality by facilitating access to credit in developing countries. In Latin America, Karpowicz (2014) demonstrates, in a study for Colombia, that reducing financial access costs improves income distribution using a general equilibrium model.

Specifically, the literature analyzed agrees that financial inclusion, both traditional and digital, can be a powerful tool for reducing poverty and inequality. However, its effectiveness depends on several structural factors: institutional quality, the country’s income level, gender inequality, digital divides, and territorial characteristics. This requires that policies be designed taking into account targeting and efficiency criteria. Much of the research has focused on analyzing FI as measured by access to financial resources. This research includes separating FI to analyze its effect on income inequality, specifically for LAC countries.

4. Data and Methodology

4.1. Data

This research was conducted in 15 Latin American and Caribbean countries between 2004 and 2021. The variable of primary interest is financial inclusion (FI), which is derived from the Financial Development Indicator of Financial Institutions created by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), developed by (Svirydzenka, 2016). This indicator has been adopted in the economic literature as a measure of financial inclusion (Khera et al., 2021; Gharbi & Kammoun, 2023).

The FI indicator is constructed from three dimensions: access, use, and efficiency of the financial system. This broad, multidimensional approach is based on the matrix of financial system characteristics developed by Čihák et al. (2012) and allows capturing the complexity of modern financial development. From an access-based FI approach, it considers the ability of individuals and businesses to access financial services and includes bank branches per 100,000 adults and ATMs per 100,000 adults. The FI indicator, which measures financial depth, refers to the size and liquidity of these institutions and is measured by loans to the private sector, pension fund assets, mutual fund assets, and life insurance premiums, all as a percentage of GDP. Finally, efficiency refers to the ability of institutions to provide financial services at a low cost and with a sustainable income, as well as the level of capital market activity (Svirydzenka, 2016).

While this indicator may encompass heterogeneous services that do not equally impact all segments of the population, its composition is informed by structural logic. Some of its components (such as mutual funds or insurance) reflect dynamics specific to the formal financial system, with a greater presence in urban and middle- or high-income sectors. However, its inclusion is relevant because these indicators enable the capture of the degree of penetration and functionality of the financial system within an economy. A deeper, more diversified, and functional financial system constitutes an enabling condition for the development of products and services adapted to traditionally excluded populations. According to Svirydzenka (2016), financial development cannot be understood solely in terms of basic access, but rather in terms of the interaction between coverage, depth, and efficiency. A financial system developed in multiple dimensions improves capital allocation, resilience, and equity when accompanied by strong institutions (Khera et al., 2021; Gharbi & Kammoun, 2023). In this sense, although not all components of the index directly affect all population groups (such as poorer or rural populations), their inclusion allows for a more comprehensive analysis of the structural conditions that determine access to and use of the financial system.

To address this limitation, this study does not limit itself to analyzing the aggregate FI index but instead performs differentiated estimates by its components. Specifically, in this indicator, the access dimension, measured by the number of ATMs and branches per 100,000 adults, serves as a proxy for the minimum physical availability of financial services and can capture more basic forms of financial inclusion, which are more likely to reach larger segments of the population (such as the poorest or rural populations). Meanwhile, the use of the depth dimension, which encompasses the volume of credit extended to the private sector and others, serves as a reflection of the level of activity and maturity of the financial system, facilitating the progressive inclusion of population segments. This methodological strategy enables the identification of the channels through which FI can be linked to poverty and inequality reduction. It avoids drawing aggregate conclusions based on a single composite index.

Evolution of IF, Poverty, and Inequality

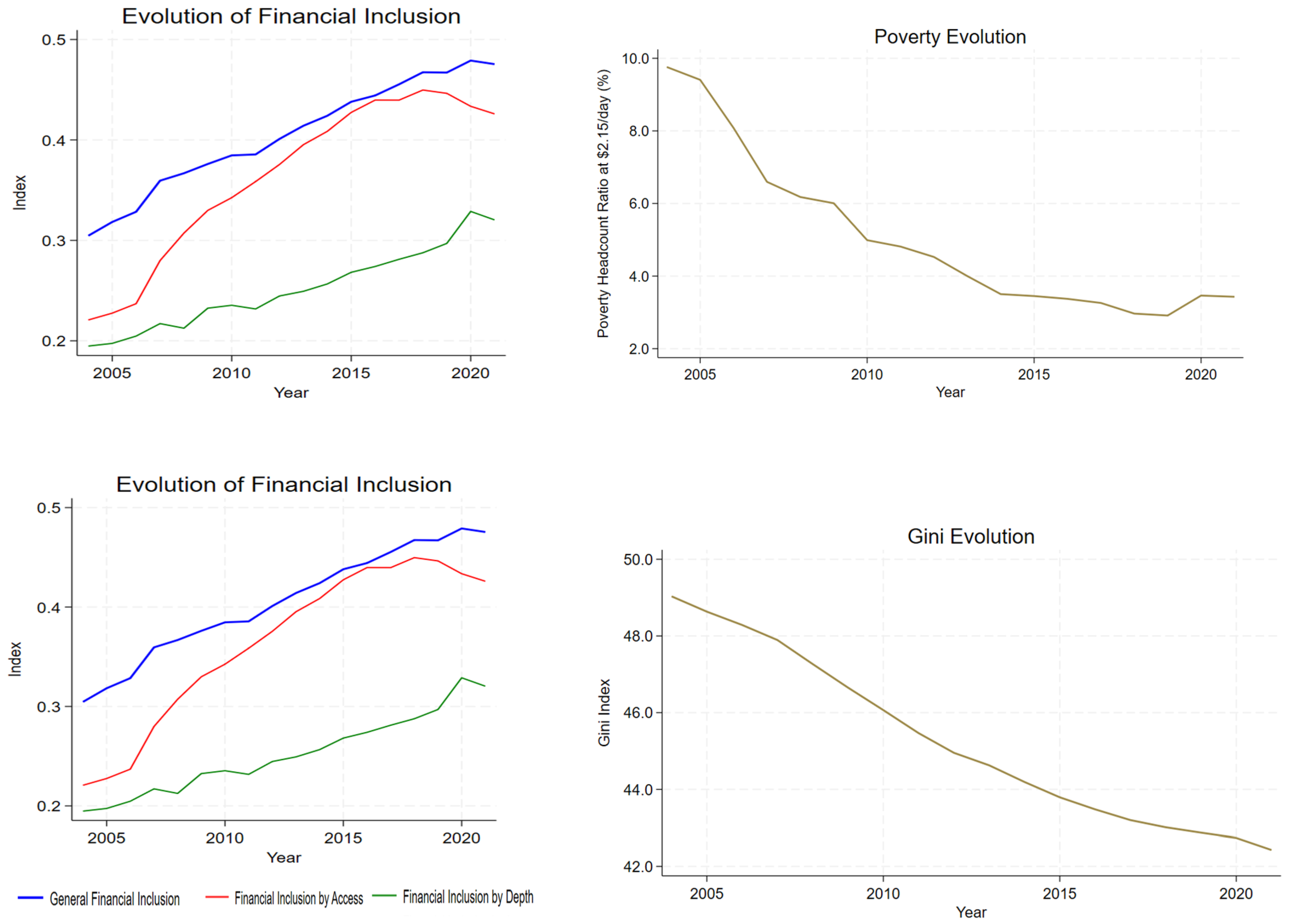

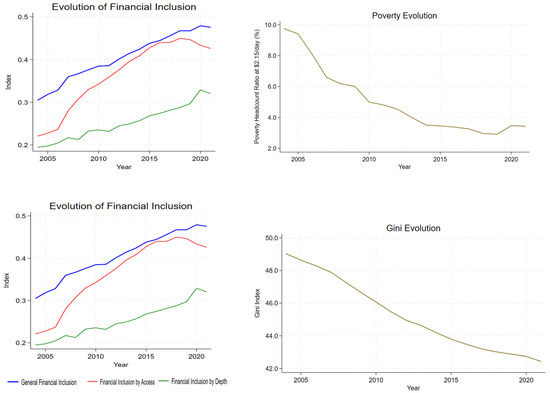

The graphs presented show a progressive improvement in financial inclusion (FI) in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) between 2004 and 2021, both in its overall dimensions and in terms of access and use. By 2021, overall FI grew 56% compared to 2004, from 0.30 to 0.48 points. During the same period, FI by access grew 92%, from 0.22 to 0.43. FI by use or depth grew 64%, from 0.19 to 0.32. In Latin America and the Caribbean, FI by access has evolved and has been more prevalent over time than FI by use of financial services. These figures indicate a lower level of FI compared to other countries with high financial development, such as the United States (0.83) and (0.80), and South Korea (0.66) and (0.86) in access and depth, respectively, as of 2021.

On the other hand, when compared with the evolution of the IF (Figure 1), it is observed that the IF has had an increasing trend over time, while poverty and income inequality have decreased between 2004 and 2021. Specifically, the poverty rate (the percentage of the total population living on less than $2.10 a day at 2017 international prices) has decreased by an average of 65% in LAC countries, from 9.76% to 3.42%, between 2004 and 2021. The Gini coefficient (an index calculated based on income after taxes and social transfers) decreased by an average of 13%, from 49.03 to 42.43, during the same period (World Bank, 2021).

Figure 1.

Evolution of total IF, poverty, and average inequality in LAC. Source: International Monetary Fund and World Bank.

However, this reduction in poverty and inequality was heterogeneous across LAC countries, and in some cases, can be attributed mainly to the expansion of social policies, such as conditional cash transfers. For example, programs such as Bolsa Familia (Brazil) increased the income of the poorest households, contributing to poverty reduction, and had positive distributive effects by proportionally increasing the income of the lowest decile of the population, thereby reducing the Gini coefficient (Magalhães et al., 2024; Nazareno & de Castro Galvao, 2023; Lustig et al., 2014). Conditional cash transfers are determining factors in the improvement in the well-being of vulnerable households (Fiszbein & Schady, 2009). This pattern suggests that the effect of conditional transfers can explain part of the reduction in poverty and inequality in the region. However, these policies also served as financial access mechanisms, requiring the opening of bank accounts to collect transfers, which may have generated a complementary inclusion effect. The reduction in poverty and inequality observed in this study may reflect an interaction between both mechanisms.

On the other hand, it is important to mention that, although the present study uses the Poverty Headcount Ratio at $2.15 a day (PPP, constant 2017 prices), this metric does not incorporate mandatory household expenditures, such as transportation, food, health, education, or basic services, which can significantly affect real disposable income. However, it is a standardized and widely used measure in poverty studies (Jensen & Naveed, 2025; Castilho & Fuinhas, 2025; Alom et al., 2025). To complement this limitation, the study also includes the Gini coefficient as a measure of inequality, which allows for capturing overall distributional effects, including those arising from differences in disposable income between socioeconomic groups. While the poverty line establishes an absolute threshold, the Gini coefficient reflects the relative distribution of income. It can indirectly capture the structural constraints imposed by fixed expenditures, especially on the most vulnerable households.

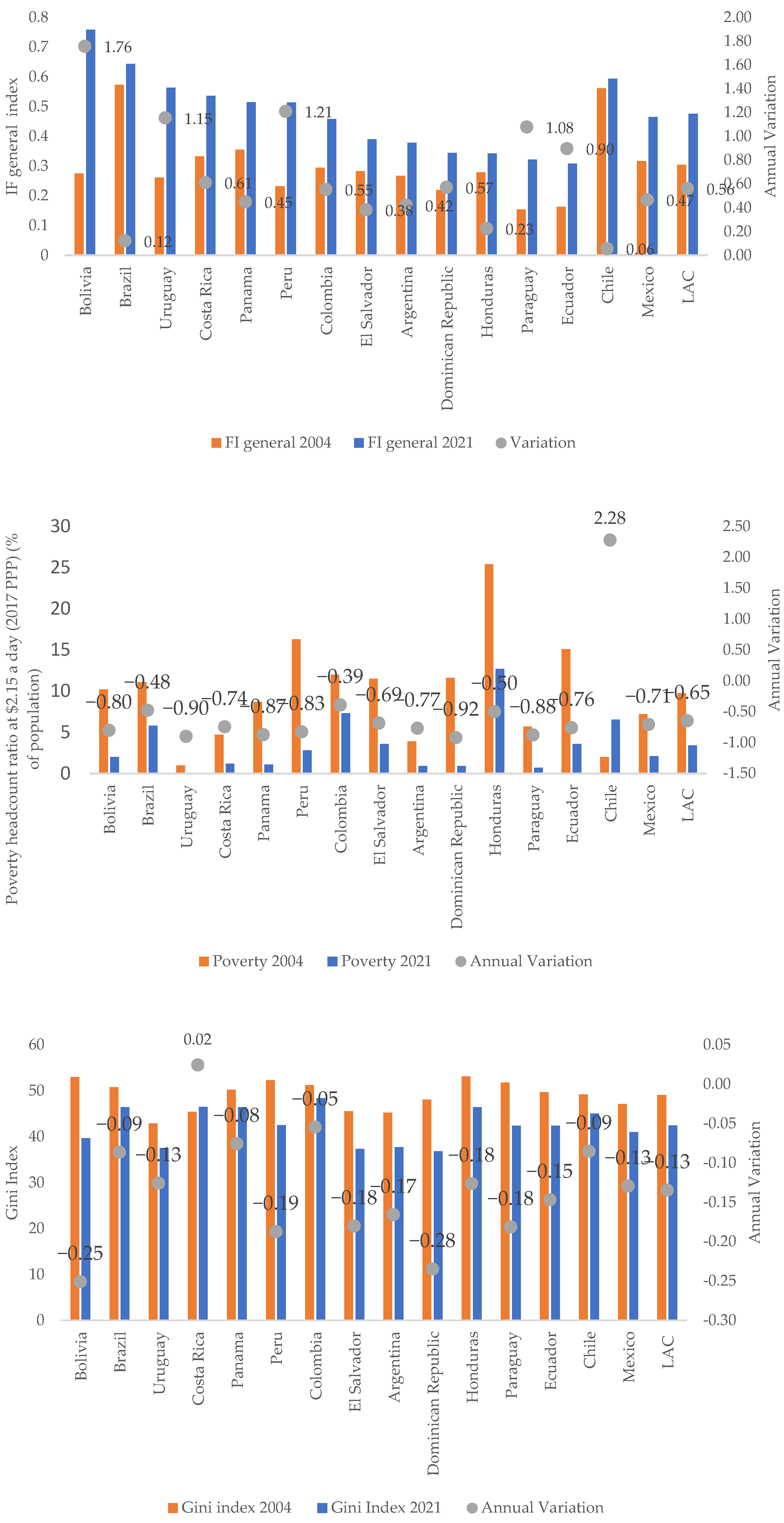

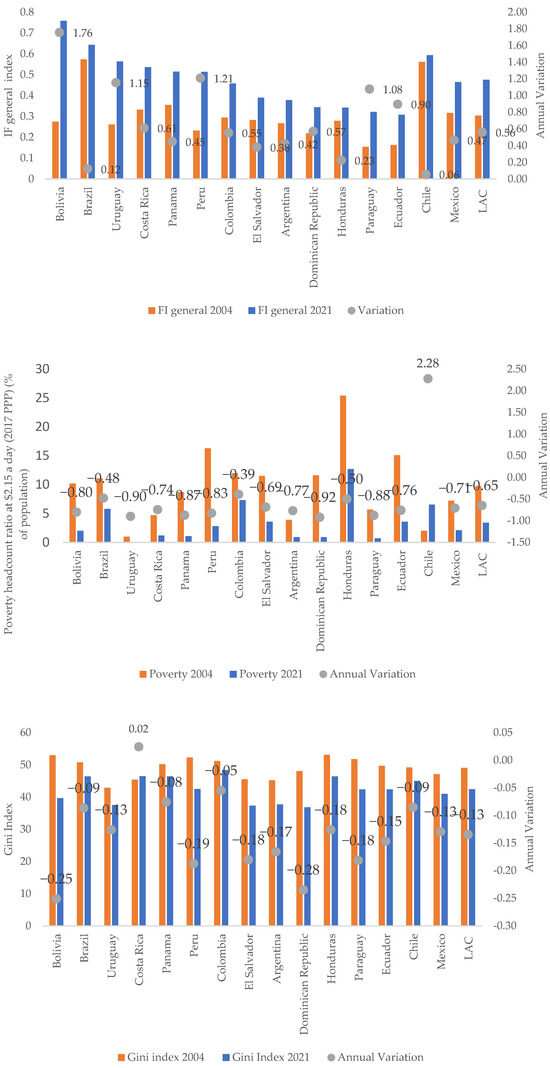

Figure 2 allows us to observe the variations in the variables of interest for country comparisons. Regarding FI, Bolivia stands out as the country in the region with the most significant variation in the FI indicator (176%) for 2021, reflecting a notable expansion in access to and use of financial services in the country. This evolution can be attributed to policies such as the banking of social bonds and the presence of financial institutions in rural areas. In contrast, Chile exhibited the lowest variation in the region (6%), which may be attributed to its already high levels of financial inclusion in previous years, reflecting more stable growth.

Figure 2.

FI General Index, Poverty and Gini index by country, variation 2004–2021. Source: International Monetary Fund and World Bank.

Regarding poverty, almost all countries experienced a decline during this period. Bolivia and Peru led the way, with significant drops in their poverty rates (−80% and −83% respectively), consistent with their improvements in financial inclusion (more than 100%). Regarding the Gini coefficient, the trend is more moderate. Although most countries show reductions in inequality, the decline has been less pronounced than that of poverty. Bolivia and the Dominican Republic show the most significant reductions of 23% and 25% respectively. On the other hand, Colombia experienced the lowest reduction in inequality in 2021 (5%) and also a low increase in its FI (6%).

Table 1 shows brief descriptive statistics for the variables used in the model. In addition, macroeconomic control variables were used, following the empirical literature of previous studies by Omar and Inaba (2020), Mushtaq and Bruneau (2019), and Park and Mercado (2015). The variables included were annual GDP growth, private credit, inflation, and secondary school enrollment rate. Specifically, the secondary school enrollment rate (education) is used to control for human capital accumulation. The inflation rate is added as a control variable following Easterly and Fischer (2001), Dollar and Kray (2002), and Kim and Lin (2023), who document evidence that the inflation rate is indeed a significant determinant of poverty. Furthermore, it is crucial to determine whether financial inclusion affects countries in the low-income bracket, given its impact on GDP. Therefore, GDP growth is also included (Neaime & Gaysset, 2018). Credit to GDP is a variable used to measure financial development, indicating the differences in the financial market that exist among countries related to financial inclusion. A table containing variable definitions and sources is included in Appendix A. Also, we included in Appendix B a correlation matrix between the main variables where an inverse and significant relationship is identified between FI and poverty and FI and inequality, both at the general level, measured by access and use.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the variables to be used in the model.

4.2. Methodology

A panel data model was employed to examine the impact of FI on poverty and income inequality, using data from 15 LAC countries over the period 2004–2021. This approach combines both cross-sectional and time-series dimensions to capture dynamic effects.

The relationship between financial inclusion, income distribution, and poverty/inequality is not unidirectional. It could include reverse causality (Neaime & Gaysset, 2018), which implies a significant risk of endogeneity in the relationship between financial inclusion and poverty or inequality. While greater financial inclusion can contribute to reducing poverty and inequality, it is also true that poorer or more unequal societies can limit, restrict, or distort the scope of financial inclusion with greater structural barriers to accessing financial services. These endogeneity effects can lead to potential biases in the estimated coefficients.

To correct for potential endogeneity problems and analyze the effect of financial inclusion on poverty and income inequality in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), the two-stage System GMM estimator with robust errors is used (Arellano & Bover, 1995; Blundell & Bond, 1998). This method enables the internal instrumentation of potentially endogenous variables through their lags, under the assumption of weak exogeneity.

In this research, the lag of the dependent variable (poverty or inequality) is included as an explanatory variable to capture its temporal dynamics and possible persistent effects, introducing an autoregressive structure (Beck et al., 2007). Furthermore, the financial inclusion variable is considered potentially endogenous. Therefore, both it and the lag of the dependent variable are instrumented through GMM using their lags from the second period as internal instruments. The estimation is carried out under the two-step robust approach, which corrects standard errors for heteroskedasticity, providing more efficient and consistent estimates in the presence of non-constant variance (Neaime & Gaysset, 2018). This methodology is suitable for addressing problems of endogeneity, heteroskedasticity, and autocorrelation commonly found in panel data. Macroeconomic control variables (GDP growth, secondary school enrollment, credit to the private sector, and inflation) are included in the model in their differentiated form.

The generalized estimated model follows the following general form:

where:

- is the annual change in the dependent variable Poverty (percentage of the total population living on less than $2.10 a day at 2017 international prices)/Gini coefficient for the country in year , respectively.

- is the first lag of the dependent variable (Poverty (percentage of the total population living on less than $2.10 a day at 2017 international prices)/Gini coefficient) that introduces dynamics, respectively.

- represents the financial inclusion index measured at (1) the overall level, (2) by access to, or (3) by use of financial services in the country during the year , respectively. Variables normalized between 0 and 1 using a min–max transformation, which reflects the relative change in financial inclusion in overall terms, access to, or use of formal financial services.

- is a vector of macroeconomic control variables including (d. GDP growth, d. secondary enrollment, d. credit to the private sector, and d. inflation) in the country during the year .

- is the idiosyncratic error.

The first equation examined the relationship between financial inclusion and poverty, while the second equation assessed the association between financial inclusion and income inequality. Each of these equations is evaluated for each financial inclusion indicator: (1) at the overall level, (2) measured by access to financial services, and (3) measured by use of financial services. To facilitate cross-country and temporal comparisons, the financial inclusion index was rescaled using a min-max normalization, standardizing its values between 0 and 1.

The motivation for using GMM in the present study is based on several justifications, supported by previous studies such as those of Seifelyazal et al. (2023), Khan and Khan (2024) and Md Jamil et al. (2024) who have used this dynamic GMM method, combined with the Hansen test and AR tests, to explore the same financial inclusion variables in relation to inequality and poverty.

Evaluating the Validity of the GMM Model

After estimating using the Two-Step System Generalized Method of Moments with robust standard errors, various diagnostic tests are applied to verify the model’s validity and the consistency of the instruments used.

First, the Arellano–Bond test is conducted to detect serial correlation in the error terms. The absence of second-order autocorrelation (AR(2)) is a key requirement for the validity of lagged instruments. In all the models estimated in this study, the AR(2) statistics are not significant, indicating no evidence of second-order serial correlation. This supports the validity of the instruments in this regard.

Second, the joint validity of the instruments is evaluated using Hansen’s overidentification test. The Hansen test does not reject the null hypothesis of instrument validity (p-values > 0.1), which supports both the joint validity of the instruments and the consistency of the GMM estimator applied in this research.

Furthermore, a strategy to reduce the number of instruments generated in the GMM estimation is adopted (using the collapse option), in order to prevent model overfitting and minimize the risk of invalidating the overidentification tests—a practice recommended by Roodman (2009).

Overall, the results of the diagnostic tests support the validity of the estimated models, the appropriateness of the instruments used, and the consistency of the estimators obtained. The results are shown in Table 2 and Table 3.

Table 2.

Regression Results GMM estimates of Financial Inclusion and Poverty headcount ratio, 2004–2021.

Table 3.

Regression Results GMM estimates of Financial Inclusion and GINI Index, 2004–2021.

5. Results

To address the heterogeneity of the financial inclusion phenomenon, the analysis is conducted not only based on the aggregate index, but also by disaggregating its components: access and use. This breakdown allows us to assess which dimensions are related to changes in poverty and inequality, recognizing that access alone may not be sufficient, and that active use or the cost of services can determine the ultimate impact on well-being.

First, the effect of FI on poverty in Latin American and Caribbean countries is presented. The analysis is then disaggregated by access to FI and by financial services. The same procedure is used to analyze the effect of general financial infrastructure, access to financial services, and use of financial institutions on income inequality in LAC countries.

A dynamic panel data model, estimated using the two-stage System GMM method with robust errors, was employed to analyze the effect of financial inclusion on poverty and inequality in 15 Latin American and Caribbean countries over the period 2004–2021. Since financial inclusion and social variables can influence each other, potential endogeneity is corrected for using internal instruments (lags) under weak exogeneity assumptions.

5.1. Influence of Financial Inclusion on Poverty

The estimation results shown in Table 2 show that FI reduces poverty in LAC. Specifically, it is observed that a one-unit increase in the variation in the general financial inclusion index generates a reduction of 8.02 percentage points in the annual variation in poverty (Model 1a). When analyzing the disaggregation of Financial Inclusion, it is found that a one-unit increase in the variation in the financial inclusion index measured by access to financial services generates a 12.7 percentage point reduction in the annual variation in poverty (Model 2a). Meanwhile, a one-unit increase in the variation in the financial inclusion index measured using financial services generates a 10.8 percentage point reduction in the annual variation in poverty (Model 3a).

These results are consistent with existing literature and confirm that FI contributes to poverty reduction in LAC. This is because it enables people living in poverty to access and use financial products and services, such as bank accounts, loans, and insurance, which are essential for managing their income, saving for the future, and coping with emergencies. Access to credit or savings reduces the vulnerability of low-income households to external shocks, such as job loss or health emergencies, as it enables the poor to manage their resources better, invest in their future, and break the cycle of poverty. This also facilitates stable consumption and the start-up of small businesses. This effect is particularly relevant in LAC, where labor informality is high and the incomes of the poorest families are often unstable. Otherwise, without access to and use of these services, poor people find themselves trapped in a cycle of economic vulnerability and limited ability to improve their situation (Chliova et al., 2015).

Furthermore, these results contribute to research on LAC by highlighting that access is a more important determinant of poverty reduction than the use or depth of financial services in FI. By demonstrating that access has a more significant impact, they underscore the importance of removing entry barriers, such as a lack of infrastructure or geographic exclusion, which could inform new policies aimed at expanding basic access and achieving more effective inclusion before focusing on increasing use or depth. Access to financial services is the first step toward FI and allows more people to enter the formal system, contributing to poverty reduction. Without access, use, and depth, one cannot fully develop.

5.2. Influence of Financial Inclusion on Income Inequality

Table 3 shows the estimates. The results reveal a significant relationship between FI and the reduction in income inequality in LAC countries. Specifically, a one-unit increase in the change in the overall financial inclusion index is associated with a 5.88-point reduction in the annual change in the Gini coefficient, suggesting a significant decrease in income inequality (Model 1b). Analyzing financial inclusion in its disaggregated form, it is observed that a one-unit increase in the change in the financial inclusion index measured by access to financial services is associated with a 3.56-point reduction in the annual change in the Gini coefficient. Meanwhile, a one-unit increase in the change in the financial inclusion index measured using financial services is associated with a 6.58-point reduction in the annual change in the Gini coefficient, suggesting a significant decrease in income inequality in LAC.

It is shown that income inequality in LAC countries can be reduced through greater financial inclusion. Increased FI improves access to resources such as credit and savings, allowing people to increase their capital, invest in entrepreneurship, and access better job opportunities. This could reduce the income gap, especially among disadvantaged groups, by encouraging their participation in the economy (Adeleke & Olomola, 2022). On the other hand, the results confirm that exclusion from the financial system could exacerbate existing income inequalities, benefiting only those with a certain level of resources. Therefore, FI policies must ensure that all segments of the population can participate in and benefit from advanced financial services.

Furthermore, it is shown that in LAC, FI, measured by the use and expansion of financial services and products, significantly reduces income inequality. This suggests that people need access to essential services and use these financial tools to improve their economic situation, such as credit, investments, and insurance. This would encourage the accumulation of resources and the ability to generate income. At the same time, access only opens the door, but does not guarantee its effective use to improve economic conditions that allow narrowing the income gap. This is especially true in a region like LAC, which has high levels of inequality. These results have implications for strategies and policies, where the focus has traditionally been on increasing access to financial services without deeply considering how their practical use and expansion can generate real change in reducing inequality. This approach suggests the need to reach a broader audience and encourage the use of financial products, which can have a direct and lasting impact on improving the income of the most disadvantaged groups.

The results reinforce the importance of public policies for financial inclusion as a mechanism for reducing poverty and inequality in LAC. Facilitating access to financial products and services is a key first step toward integrating marginalized populations into the formal economy. However, the impact on inequality depends on the effective and continued use of these services. This finding is consistent with previous studies that emphasize the importance of complementing banking access with strategies that promote trust in the financial system and mitigate barriers to its use, such as financial education and the digitalization of transactions (Allen et al., 2016; Cámara & Tuesta, 2014). This suggests that policies should focus on expanding financial infrastructure and ensuring that the entire population effectively utilizes available services. This promotes more equitable and sustainable economic growth. Furthermore, the results indicate that financial inclusion has a more significant impact on reducing poverty and inequality when accompanied by a favorable economic environment. Therefore, it is essential to ensure a stable and accessible institutional environment that guarantees the continuity and availability of these services.

6. Conclusions and Policy Implications

This study aims to determine the relationship between financial inclusion, poverty, and income inequality in LAC countries. To do so, it uses data from the financial inclusion indicator constructed by the International Monetary Fund for 15 LAC countries. Unlike related studies, this study identifies this influence by analyzing financial inclusion at the overall level and disaggregating FI as measured by access to and use of financial services. This contributes to assessing the comparative effectiveness of financial inclusion policies in reducing poverty and inequality.

The results obtained using a panel data model with a two-stage GMM methodology and robust errors demonstrate a significant relationship between financial inclusion and the reduction in poverty and inequality in LAC. A one-unit increase in the change in the overall financial inclusion index generates an 8.02 percentage point reduction in the annual change in poverty, while FI measured by access reduces poverty by 12.7 percentage points, and FI measured by use reduces poverty by 10.8 percentage points. This suggests that access to financial services has a greater impact on poverty reduction than their use. In other words, simply allowing people to enter the formal financial system, for example, with a bank account, already represents a significant advance for vulnerable sectors. This access helps generate savings capacity and reduces exposure to economic shocks, essential elements for breaking the cycle of structural poverty. Thus, access acts as a gateway to financial stability.

Regarding income inequality, a one-unit increase in the change in the overall financial inclusion index is associated with a 5.88-point reduction in the annual change in the Gini coefficient. Regarding the financial inclusion index, measured by access to financial services, reduces the yearly variation in the Gini coefficient by 3.56 points, and FI, measured by the use of financial services, reduces the annual variation in the Gini coefficient by 6.58 points, suggesting a significant decrease in income inequality. In this case, the effect of FI measured by the use and depth of financial services on reducing income inequality is much more significant than that of FI measured by access. Therefore, the results show that the effective use of financial services (such as credit, savings, or insurance) has a greater impact. This implies that while expanding access may be sufficient to tackle poverty, reducing inequality requires individuals to make active and diversified use of available financial services. Therefore, reducing inequality requires not only expanding financial coverage but also ensuring that the available services are functional, affordable, and tailored to the realities of each social group.

These results contribute to a clear differentiation between the effects of financial inclusion on poverty reduction and income inequality in LAC. While many policies have treated FI as a uniform concept, these findings show that financial access is key to reducing poverty. Meanwhile, the use and expansion of financial services have a much more significant impact on reducing inequality.

The implications for public policy design are significant. If the goal is to reduce poverty, strategies should focus on eliminating barriers to access to the financial system, promoting the expansion of banking and digital infrastructure, opening low-cost, simplified accounts, and providing basic financial education. Conversely, if the goal is to reduce income inequality, incentives for the active use of financial products, such as productive credit, insurance, and investment, must be strengthened. The first steps to implement would be to improve the infrastructure and reduce regulatory barriers to expand access to banking. The following steps are to ensure that people use these services sustainably. In this regard, it is crucial to promote financial education, strengthen trust in the financial system, and expand digital solutions that facilitate access to services among the most vulnerable sectors. Likewise, the formalization of micro and small businesses through financial inclusion can play a crucial role in generating employment and social mobility. By enabling access to digital financing and payment tools, entrepreneurs can improve their productivity and financial stability, ultimately contributing to a sustained reduction in inequality.

Additionally, it is recognized that financial inclusion is not an automatic solution. In contexts where available services present high costs, excessive interest rates, or quality barriers, they can become extractive mechanisms that deepen the vulnerability of the poorest. This implies that policies must not only expand access and use but also ensure the efficiency, affordability, and sustainability of the financial products offered. This requires governments and financial institutions in LAC to adopt differentiated approaches, avoiding generalized strategies and focusing on specific interventions, as well as adequate regulations that enable formal financial inclusion (access, use, and efficiency) for the most marginalized. This evidence suggests that effective financial inclusion does not depend solely on expanding coverage and use but also on ensuring equitable, accessible, and sustainable conditions, which has direct implications for the design of differentiated policies by type of service and target population.

For future research, it is recommended that the role of financial digitalization and its impact on the most vulnerable segments of the population be analyzed. Furthermore, more research is needed on the interaction between financial inclusion and transfer policies to analyze the effects of social subsidies on poverty and inequality in the region. Additionally, a significant limitation of this study is the lack of direct information on the conditions of access and the actual costs of financial services used by households, particularly in the case of credit. Future research should incorporate variables such as effective interest rates, over-indebtedness, fees, quality, or financial risk indicators to assess whether financial inclusion is truly enabling or whether it reproduces exclusion mechanisms in other forms. Additionally, we will delve deeper into the analysis of the differential effects based on the type of financial service, including bank accounts, savings, credit, and insurance.

Another limitation of this research is that the poverty measure adopted (Poverty Headcount Ratio at $2.15/day (PPP, 2017 prices), while a standardized and widely used measure, does not explicitly incorporate mandatory household expenditures, which can significantly affect real disposable income. Therefore, in the future, it would be relevant to complement the analysis with poverty measures that incorporate net disposable income, discount essential expenses, or utilize multidimensional poverty methodologies, which allow for a better capture of effective economic deprivation. This would be particularly useful to more accurately assess the effects of financial inclusion on material well-being in contexts with high fixed expenditure burdens or debt.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.R. and M.L.; methodology, J.R. and M.L.; software, M.L.; validation, J.R.; formal analysis, J.R. and M.L.; research, J.R. and M.L.; resources, J.R. and M.L.; data curation, M.L.; writing: preparation of the original draft, M.L.; writing: review and editing, J.R.; visualization, J.R.; supervision, J.R.; project administration, J.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Universidad de las Américas: PRG.ECO.23.14.01.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Financial Development created by the International Monetary Fund (IMF). https://data.imf.org/es-es?sk=f8032e80-b36c-43b1-ac26-493c5b1cd33b&sid=1480712464593 (accessed on 15 May 2024).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1 summarizes the definition of the variables used in the model and their respective sources from which they were obtained.

Table A1.

Variable and source definition table.

Table A1.

Variable and source definition table.

| Variable | Definition | Fountain |

|---|---|---|

| Index of financial institutions | Index made using principal components that measure a combination of depth, access, and efficiency of financial institutions. | IMF |

| Access to financial institutions | Ability of individuals and businesses to access financial services such as savings, credit, and insurance. The indicator measures bank branches per 1000 adults and ATMs per 100,000 adults. | IMF |

| Depth of financial institutions | Size and liquidity of financial markets. The indicator measures variables such as private-sector credit, pension fund assets, mutual fund assets and insurance premiums (to GDP). | IMF |

| Number of people living in poverty | Percentage of the population living on less than $2.15 per day, at 2017 international prices adjusted for purchasing power parity (PPP). | World Bank |

| Gini disposable | It measures inequality in the distribution of disposable income among households in an economy. Its values range from 0 (perfect equality) to 100 (total inequality). | World Bank |

| GDP growth | Percentage change in a country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) at market prices, adjusted for inflation. It reflects the rate at which a country’s economy is growing or shrinking from one year to the next, based on constant local currency. | World Bank |

| Secondary school enrollment | Total enrollment in secondary education, expressed as a percentage of the population of official secondary school age. | World Bank |

| Inflation | Percentage annual variation in the cost to the average consumer of acquiring a basket of goods and services. | World Bank |

| Domestic credit | Financial resources provided by financial institutions to the private sector (such as loans, purchases of non-equity securities, trade credit, etc.), which generate a payment obligation. | World Bank |

Appendix B

Table A2.

Correlation matrix between the variables of interest.

Table A2.

Correlation matrix between the variables of interest.

| Financial Inclusion (GENERAL IF) | |

|---|---|

| Poverty Growth Rate | −0.67 *** |

| Gini Index Annual Growth | −0.778 *** |

| Financial Inclusion (ACCESS IF) | |

| Poverty Growth Rate | −0.649 *** |

| Gini Index Annual Growth | −0.726 *** |

| Financial Inclusion (USE IF) | |

| Poverty Growth Rate | −0.537 *** |

| Gini Index Annual Growth | −0.672 *** |

Standard errors in parentheses *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

References

- Abubakar, A., & Malumfashi, A. H. (2022). An empirical analysis of the impact of financial inclusion on poverty reduction in Katsina State, Nigeria. UMYU Journal of Accounting and Finance Research, 4(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Adeleke, O. K., & Olomola, P. A. (2022). An empirical investigation of financial inclusion, poverty and inequality in Nigeria. Redeemer University Journal of Management and Social Sciences, 5(2), 2–18. [Google Scholar]

- Aghion, P., & Bolton, P. (1997). A trickle-down theory of growth and development. Journal of Economic Studies, 64(2), 151–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, F., Demirguc-Kunt, A., Klapper, L., & Martinez Peria, M. S. (2016). The foundations of financial inclusion: Understanding the ownership and use of formal accounts. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 27, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alom, K., Rahman, M. Z., Khan, A. I., Akbar, D., Hossain, M. M., Ali, M. A., & Mallick, A. (2025). Digital finance leads women entrepreneurship and poverty mitigation for sustainable development in Bangladesh. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 14(1), 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antwi, F., Kong, Y., & Gyimah, K. N. (2024). Financial inclusion, competition, and financial stability: New evidence from developing economies. Heliyon, 10(13), e33723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aracil, E., Gómez-Bengoechea, G., & Moreno-de-Tejada, O. (2022). Institutional quality and the link between financial inclusion and poverty alleviation: Cross-country empirical evidence. Istanbul Stock Exchange Journal, 22(1), 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, M., & Bover, O. (1995). Another look at the instrumental variable estimation of error-components models. Journal of Econometrics, 68(1), 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmeh, C. (2025). Financial globalization, poverty, and inequality in developing countries: The moderating role of Fintech and financial inclusion. Research in Globalization, 10, 100277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Gamboa, J., Cabrera-Barona, P., & Jácome-Estrella, H. (2021). Financial inclusion and multidimensional poverty in Ecuador: A spatial approach. World Development Prospects, 22, 100311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachelet, P. (2024, March 6). The complexities of inequality in Latin America and the Caribbean. Inter-American Development Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Barra, C., D’Aniello, C., & Ruggiero, N. (2024). The effects of bank types on financial access and income inequality in a heterogeneous sample: A quantile regression analysis. Journal of Economics and Business 131, 106197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, T., Demirguc-Kunt, A., & Honohan, P. (2009). Access to financial services: Measurement, impact, and policy. The World Bank Research Observer, 24(1), 119–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, T., Demirgüç-Kunt, A., & Levine, R. (2007). Finance, inequality and the poverty. Journal of Economic Growth, 12, 27–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundell, R., & Bond, S. (1998). Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics, 87(1), 115–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolarinwa, S. T., & Akinlo, A. E. (2021). Is there a nonlinear relationship between financial development and income inequality in Africa? Evidence from the dynamic panel threshold. Journal of Economic Asymmetries, 24, e00226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruck, C. (2006, October 22). Millions for millions. The New Yorker. [Google Scholar]

- Cassimon, S., Maravalle, A., González Pandiella, A., & Turroques, L. (2022). Determinants of and barriers to people’s financial inclusion in Mexico (OECD economics department working papers). OECD. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castilho, D., & Fuinhas, J. A. (2025). Exploring the effects of tourism capital investment on income inequality and poverty in the European Union countries. Journal of Economic Structures, 14(1), 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cámara, N., & Tuesta, D. (2014, September 22). Measuring financial inclusion: A muldimensional index. BBVA research paper No. 14/26. BBVA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chliova, M., Brinckmann, J., & Rosenbusch, N. (2015). Is microcredit a boon to the poor? A meta-analysis examining development outcomes and contextual considerations. Journal of Business Entrepreneurship, 30(3), 467–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čihák, M., Demirgüç-Kunt, A., Feyen, E., & Levine, R. (2012). Benchmarking financial development around the world (6175). World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- de la Cuesta-González, M., Ruza, C., & Rodríguez-Fernández, J. M. (2020). Rethinking the nexus between income inequality and financial development. A study of nine OECD countries. Sustainability, 12(13), 5449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirgüç-Kunt, A., Klapper, L., Singer, D., & Ansar, S. (2022). The Global Findex Database 2021: Financial inclusion, digital payments, and resilience in the age of COVID-19. World Bank Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Demirgüç-Kunt, A., Klapper, L., Singer, D., Ansar, S., & Hess, J. (2018). The global findex database 2017: Measuring financial inclusion and the fintech revolution. World Bank, International Telecommunication Union. [Google Scholar]

- Dollar, D., & Kray, A. (2002). Growth is good for the poor. Journal of Economic Growth, 7(3), 195–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterly, W., & Fischer, S. (2001). Inflation and the poverty. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 33(2), 160–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ECLAC. (2025, February 26). ECLAC launches the 2024 edition of the Statistical Yearbook with relevant data on the economic, social, and environmental situation in Latin America and the Caribbean. ECLAC. [Google Scholar]

- Erlando, A., Riyanto, F. D., & Masakazu, S. (2020). Financial inclusion, economic growth, and poverty alleviation: Evidence from eastern Indonesia. Heliyon, 6(10), e05235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiszbein, A., & Schady, N. R. (2009). Conditional cash transfers. The World Bank. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, J., & Matray, A. (2024). Financial inclusion, economic development, and inequality: Evidence from Brazil. Journal of Financial Economics, 156, 103854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galor, O., & Zeira, J. (1993). Income distribution and macroeconomics. Journal of Economic Studies, 60(1), 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharbi, I., & Kammoun, A. (2023). Developing a multidimensional financial inclusion index: A comparison based on income groups. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 16(6), 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girma, A. G., & Huseynov, F. (2023). The causal relationship between financial technology, financial inclusion, and income inequality in African economies. Journal of Risk Management and Finance, 17(1), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Findex. (2021). Global findex 2021 database: Financial inclusion, digital payments, and resilience in the era of COVID-19. The World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Mexico. (2012, July 10). The offering of payroll loans by SOFOMES (National Insurance Companies). CONDUSEF, National Commission for the Protection and Defense of Financial Services Users. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S., & Kanung, R. P. (2022). Financial inclusion through digitalization: Economic viability for the base of the pyramid (BOP) segment. Journal of Business Research, 148, 262–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Monetary Fund (IMF). (2021). Financial development index database. Available online: https://data.imf.org/?sk=f8032e80-b36c-43b1-ac26-493c5b1cd33b (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Jensen, A. C. H., & Naveed, A. (2025). Assessing the role of microfinance in mitigating income inequality: New evidence from a global context. Social Indicators Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpowicz, I. (2014). Financial inclusion, growth and inequality: A model application to Colombia (p. 166). IMF. [Google Scholar]

- Kebede, J., Naranpanawa, A., & Selvanathan, S. (2023). The nexus between financial inclusion and income inequality: A case from Africa. Economic Analysis and Policy, 77, 539–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I., & Khan, I. (2024). Financial inclusion matter for poverty, income inequality and financial stability in developing countries: New evidence from public good theory. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 19(11), 3561–3580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khera, P., Ng, S., Ogawa, S., & Sahay, R. (2021). Measuring digital financial inclusion in emerging market and developing economies: A new index. International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.-H., & Lin, S.-C. (2023). Income inequality, inflation and financial development. Journal of Empirical Finance, 72, 468–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kling, G., Pesqué-Cela, V., Tian, L., & Luo, D. (2022). A theory of financial inclusion and income inequality. European Journal of Finance, 28(1), 137–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V. (2023). Does financial inclusion affect poverty? A developing country analysis. Asian Economic Letters, 4(3), 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lustig, N., Pessino, C., & Scott, J. (2014). The impact of taxes and social spending on inequality and poverty in Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Mexico, Peru, and Uruguay. Public Finance Review, 42(3), 287–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, J., Ziebold, C., Evans-Lacko, S., Matijasevich, A., & Paula, C. S. (2024). Health, economic and social impacts of the Brazilian cash transfer program on the lives of its beneficiaries: A scoping review. BMC Public Health, 24(1), 2818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mbona, N. (2022). Impacts of overall financial development, access, and the depth of income inequality. Economies, 10(5), 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Md Jamil, A. R., Law, S. H., Khair-Afham, M. S., & Trinugroho, I. (2024). Financial inclusion and income inequality in developing countries: The role of aging populations. Research in International Business and Finance, 67, 102110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, S., Li, S., Tunio, R. A., Das, G., & Jamali, R. H. (2025). Financial inclusion as a catalyst for poverty reduction: Unraveling the impact amid global challenges. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 27(2), 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Daud, S. N., Ahmad, A. H., & Trinugroho, I. (2024). Financial inclusion, digital technology, and economic growth: Further evidence. Research in International Business and Finance, 70, 102361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, R., & Bruneau, C. (2019). Microfinance, financial inclusion, and ICT: Implications for poverty and inequality. Technology in Society, 59, 101154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazareno, L., & de Castro Galvao, J. (2023). The impact of conditional cash transfers on poverty, inequality, and employment during COVID-19: A case study from Brazil. Population Research and Policy Review, 42(2), 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neaime, S., & Gaysset, I. (2018). Financial inclusion and stability in MENA: Evidence from poverty and inequality. Finance Research Letters, 24, 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, M. A., & Inaba, K. (2020). Does financial inclusion reduce poverty and income inequality in developing countries? A panel data analysis. Journal of Economic Structures, 9(1), 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orazi, S., Martinez, L. B., & Vigier, H. P. (2023). Determinants and evolution of financial inclusion in Latin America: A demand side analysis. Quantitative Finance and Economics, 7(2), 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osuma, G. (2025). the impact of financial inclusion on poverty reduction and economic growth in Sub-Saharan Africa: A comparative study of digital financial services. Open Access Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 11, 101263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.-Y., & Mercado, R. (2015). Financial inclusion, poverty, and income inequality. The Singapore Economic Review, 63(01), 185–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, X. T. T., & Luu, T. B. (2024). The effect of FinCredit on income inequality: The moderating role of financial inclusion. Journal of Quantitative Finance and Accounting, 62(3), 953–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrovito, F., & Pozzolo, A. F. (2021). Credit constraints and exports of SMEs in emerging and developing countries. Small Business Economics, 56(1), 311–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piketty, T., & Sáez, E. (2014). Long-term inequality. Science, 344(6186), 838–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polloni-Silva, E., da Costa, N., Moralles, H. F., & Sacomano Neto, M. (2021). Does financial inclusion reduce poverty and inequality? A panel data analysis for Latin American countries. Social Indicators Research, 158(3), 889–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quispe Mamani, J. C., Aguilar Pinto, S. L., Calcina Álvarez, D. A., Quispe Layme, M., Gutierrez Toledo, G. P., Condori Condori, G. T., Vargas Espinoza, L., Quispe Layme, W., Marca Maquera, H. R., & Rosado Chávez, C. A. (2024). Determinants of financial inclusion in households in Peru. Frontiers in Sociology, 9, 1196651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez, C., Castelán, H., Winkler, C., Garcia, L., & Castellanos, E. (2024, November 12). Poverty in Latin America: 10 facts we need to know in 2024. World Bank Blogs. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas-Suárez, L. (2016). Financial inclusion in Latin America: Facts, obstacles and central banks’ policy issues. Discussion Paper No. IDB-DP-464. Department of Research and Chief Economist: Inter-American Development Bank. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roodman, D. (2009). How to do xtabond2: An introduction to difference and system GMM in Stata. The Stata Journal, 9(1), 86–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S. K., & Qin, J. (2023). Financial inclusion and poverty alleviation: An empirical examination. Economic Change and Restructuring, 56(1), 409–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarma, M., & Pais, J. (2011). Inclusion and Financial Development. Journal of International Development, 23(5), 613–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawadogo, R., & Semedo, G. (2021). Financial inclusion, income inequality, and institutions in sub-Saharan Africa: Identifying inequality regimes across countries. International Economics, 167, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmied, J., & Marr, A. (2016). Financial inclusion and poverty: The case of Peru. Regional and Sectoral Economic Studies, 16(2), 29–43. [Google Scholar]

- Seifelyazal, M., Salaheldin, A., & Assem, M. (2023). The Impact of Financial Inclusion on Income Inequality. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 11(06), 255–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, D., Demirguc-Kunt, A., Klapper, L., & Singer, D. (2017, April). Financial inclusion and inclusive growth: A review of recent empirical evidence. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 8040. World Bank Group. [Google Scholar]

- Suhrab, M., Chen, P., & Ullah, A. (2024). The nexus between digital financial inclusion and income inequality: Can technological innovation and infrastructure development help achieve the sustainable development goals? Technology in Society, 76, 102411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svirydzenka, K. (2016, January). Introducing a new broad-based index of financial development. IMF working paper no. 2016/005. Strategy, policy and review department (p. 43). IMF. [Google Scholar]

- Tabash, M. I., Ezequiel, O., Ahmed, A., Oladiran, A., Elsantil, Y., & Lawal, A. I. (2024). Examining the links between financial inclusion, economic growth, poverty and inequality reduction in Africa. African Scientist, 23, e02096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, M., Sheng, M. S., & Wen, L. (2023). How does financial development influence carbon emissions intensity in OECD countries: Some insights from an information and communication technology perspective? Journal of Environmental Management, 335, 117553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres Oliveros, A. M., Morales Castro, A., & Alcalá Villarreal, J. L. (2017). Analysis of the impact of new regulation on Mexican SOFOMES. Journal of Caribbean Economics, (19), 103–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P., & Huang, G. (2024). Measuring systemic risk contribution: A higher-order augmented momentum approach. Financial Research Letters, 59, 104833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Z. Z. A., Badeeb, R. A., & Philip, A. P. (2023). Financial inclusion, poverty, and income inequality in ASEAN countries: Does financial innovation matter? Social Indicators Research, 169(1–2), 471–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2021). World development indicators (WDI). World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank Group. (2024). Recent trends in poverty and inequality April 2024 (pp. 1–20). Poverty and Equity Global Practice, Latin America and the Caribbean Statistical Development Team. [Google Scholar]

- Yunus, M. (2008). Creating a world without poverty: Social enterprise and the future of capitalism. World Urban Development, 4(2), 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Zins, A., & Weill, L. (2016). The determinants of financial inclusion in Africa. Review of Development Finance, 6(1), 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zmerli, S., & Castillo, J. C. (2015). Income inequality, distributive equity, and political trust in Latin America. Social Science Research, 52, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).