Abstract

This study investigates the yield-seeking behavior of income-oriented institutional investors, who are essential players in financial markets. While external pressures compelling firms to “reach for yield” are well-documented, the firm-level behavioral drivers underlying this phenomenon remain largely underexplored. Drawing on the behavioral theory of the firm, this study argues that an investor’s performance relative to their social aspiration level (the peer average) influences their yield-seeking decisions, and that this effect is moderated by “portfolio slack,” defined as unrealized gains or losses. To test this theory in the context of persistent low-yield pressure, this study constructs and analyzes a panel dataset of Japanese life insurance companies from 2000 to 2019. The analysis reveals that these investors increase their portfolio income yield after underperforming their peers and decrease it after outperforming. Furthermore, greater portfolio slack amplifies yield increases after underperformance and mitigates yield decreases after outperformance. In contrast, organizational slack primarily mitigates yield reductions after outperformance. This research extends the behavioral theory of the firm to the asset management context by identifying distinct performance feedback responses and proposing portfolio slack as an important analytical construct, thereby offering key insights for investment managers and financial regulators.

1. Introduction

Income-oriented institutional investors, such as life insurance companies and pension funds, play a critical role in modern financial markets, managing substantial capital and influencing overall economic stability. Their “reaching for yield” behavior—a tendency to invest in riskier assets to attain higher returns—is a significant concern in finance. This behavior is particularly evident in response to external pressures such as prolonged low interest rates or opportunities for regulatory arbitrage. For instance, Becker and Ivashina (2015) demonstrate this behavior in the bond market, linking it to regulatory incentives. Similarly, Choi and Kronlund (2018) explore comparable tendencies in corporate bond mutual funds, driven by fund-flow incentives and rank-chasing behavior. In a similar vein, Andonov et al. (2017) document that U.S. public pension funds increase their allocation to risky assets due to unique regulations that link their liability discount rate to the expected return on those assets. This practice allows the pension funds to use higher discount rates to report a better funding status. Furthermore, macroeconomic conditions, such as the zero-lower-bound policy, can also compel financial institutions like money market funds to significantly alter their risk profiles and product offerings (Di Maggio & Kacperczyk, 2017).

While existing finance research acknowledges the external pressures that cause institutional investors to reach for yield, the firm-level behavioral mechanisms shaping these investment decisions remain underexplored. This scholarly gap is significant because these institutions manage vast sums of capital, and their collective behavior can substantially affect overall financial market stability. A behavioral perspective provides crucial insights by recognizing that managers at these institutions operate under bounded rationality and therefore do not consistently pursue mathematically optimal yields (Cyert & March, 1963). Instead, in a world of uncertainty and complexity, managers often rely on a key heuristic: comparing their firm’s investment performance with that of their peers and assessing their own financial condition (Festinger, 1954; J. G. March & Simon, 1958). This comparative process influences the yields they subsequently target. Although some experimental studies have explored social comparison among retail investors (Andraszewicz et al., 2023; Lindner et al., 2021), how these behavioral drivers shape the risk profiles of large, highly regulated institutional investors—using real-world data—remains a significant gap in the literature. Elucidating these cognitive and social processes represents an essential research agenda that prior work has largely overlooked—one that promises to offer behavioral reference frameworks for both investment managers and financial regulators.

To address this gap, this study builds on the behavioral theory of the firm (Cyert & March, 1963) to investigate two primary questions. First, how do income-oriented institutional investors adjust their income yield in response to their yield performance relative to social aspiration levels (peer average performance)? Second, how is this relationship moderated by organizational slack and, particularly, portfolio slack? In this study, portfolio slack is defined as the value of unrealized gains or losses within a firm’s investment portfolio.

To explore these research questions, this study examines firm-level data from Japanese life insurance companies covering the period from 2000 to 2019. This sample period offers a suitable research setting, as it begins with Japan’s economy already under the Zero-Interest-Rate Policy introduced in 1999. This long-standing, low-interest-rate environment was then substantially intensified by the Bank of Japan’s aggressive Quantitative and Qualitative Easing (QQE) policy, introduced in 2013. As a result of these policies, yields on long- and super-long-term Japanese Government Bonds (JGBs)—the main investment assets for Japanese life insurance companies—trended consistently downward until 2019. Such sustained and extreme pressure makes the period ideal for observing how life insurance companies were compelled to reach for yield—a shift toward riskier assets to meet their long-term obligations.

Employing fixed-effects models on this panel dataset, this study finds evidence supporting its central hypotheses. Japanese life insurance companies increase their income yield when underperforming their peers and decrease it when outperforming. Portfolio slack significantly moderates these performance feedback responses, amplifying yield increases after underperformance and mitigating yield decreases after outperformance. Organizational slack, by contrast, primarily mitigates yield decreases after outperformance.

This study makes two primary contributions. First, it develops a specific behavioral theory tailored to income-oriented institutional investors. This theory highlights the complex interplay of peer comparison, problemistic search, and satisficing in their yield adjustment strategies. While the hypothesizing is primarily grounded in the behavioral theory of the firm, it also incorporates insights from other relevant theoretical perspectives to offer a more comprehensive explanation. Peer performance is framed not only as a reference point for aspiration levels but also, drawing on institutional theory, as a powerful institutional norm that provides legitimacy (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). The asymmetric responses to underperformance and outperformance are further theorized through the value function of prospect theory (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979) and the incentive structures outlined in agency theory (Jensen & Meckling, 1976). Applying this multi-theoretical framework, this study uncovers a deliberate response to outperformance that extends beyond simple satisficing: an active risk-reduction strategy where outperforming insurance companies intentionally lower their investment yields to realign with peer norms and reaffirm their identity as prudent fiduciaries.

Second, this study introduces and empirically validates portfolio slack as a conceptually distinct and practically influential construct in the realm of financial risk-taking. This construct is differentiated from both general organizational slack and the traditional “risk-buffer” or “capital adequacy” measures discussed in prior insurance and banking studies. Unlike these more static, firm-level capital measures, portfolio slack represents a more immediate, liquid financial cushion (or deficit) at the portfolio level, thereby enriching slack research in a financial context. Although this measure reflects several financial properties, such as liquidity potential and balance sheet flexibility, this study conceptualizes it as a unified behavioral signal. Managers operating under bounded rationality perceive this net position as a single psychological and financial buffer or a perceived shortfall. The present study identifies this buffer as a critical moderator of risk-taking.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 develops the theoretical framework and hypotheses. Section 3 describes the data and methodology. Section 4 presents the results. Section 5 discusses the findings, contributions, implications, and limitations of the study. Finally, Section 6 concludes the study.

2. Theory and Hypotheses

2.1. Performance Feedback and Aspiration Levels

The behavioral theory of the firm is fundamentally grounded in the recognition that organizational decision-makers operate under bounded rationality, constrained by imperfect information and limited cognitive capabilities (Cyert & March, 1963). In this view, rather than engaging in exhaustive optimization, firms simplify complex problems and make decisions by exploring a limited set of alternatives (Simon, 1955). Performance feedback mechanisms are central to this process, wherein organizations establish aspiration levels as benchmarks to evaluate their performance (see Shinkle, 2011, for a review). These aspiration levels act as thresholds for judging success or failure (Greve, 2003c). Although much of the early research utilized profitability measures, such as return on assets (ROA), as aspiration levels, further research has also shown that various other aspiration levels—stock prices (Mishina et al., 2010), firm growth (Kim et al., 2011), market share (Greve, 1998), product sales (Joseph et al., 2016), and the frequency of new product introductions (Tyler & Caner, 2016)—also influence corporate behavior.

A core prediction of performance feedback theory is that a performance shortfall relative to an aspiration level is identified as a problem, triggering a “problemistic search” for solutions (Cyert & March, 1963; Posen et al., 2018). As firms seek novel strategies to close the performance gap, this search often leads to increased risk-taking, which has been shown to influence a wide range of corporate behaviors, including R&D investments (Greve, 2003a), acquisitions (Iyer & Miller, 2008), and strategic change (Audia et al., 2000). Conversely, when performance exceeds aspirations, organizations tend to engage in “satisficing”. This makes them less likely to search for alternatives or implement changes, thereby reinforcing the status quo (Greve, 1998; Simon, 1956).

2.2. Social Aspirations in Asset Management

The performance feedback literature distinguishes between two primary types of aspiration levels: historical and social. While historical aspirations, based on a firm’s own past performance, reflect internal capabilities and learning processes (Levinthal & March, 1993), social aspirations, derived from peer performance, are particularly salient in industries in which external market conditions are a dominant performance factor (Kacperczyk et al., 2015). This is especially true in asset management. In this industry, the concept of reaching for yield is often driven by regulatory pressures and a low-interest-rate environment that affects all players (Becker & Ivashina, 2015), and relative performance is a key evaluation metric. Individual-level experimental studies further confirm that social motives and peer rankings significantly impact investment risk-taking (Andraszewicz et al., 2023; Lindner et al., 2021).

The significance of social aspirations in this context is further underscored by institutional and agency theories. From an institutional perspective, the social aspiration level is more than a simple benchmark; it represents a formative industry norm (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). Conformity to this norm is crucial for maintaining legitimacy in the eyes of regulators and stakeholders. Deviating from it—either by underperforming or outperforming—can attract unwanted scrutiny. Underperformance exposes the firm to stakeholder criticism for missed opportunities. Conversely, significant outperformance is perceived as excessive risk-taking, which threatens the firm’s legitimacy as a prudent fiduciary. From an agency perspective, managers (agents) are caught between the dual demands of achieving financial returns and fulfilling their fiduciary duties to policyholders (principals), which inherently require balancing adequate returns with long-term asset safety. Their decisions reflect a continuous effort to balance these potentially conflicting interests.

This study focuses on social aspiration levels to understand the yield adjustments of Japanese life insurance companies, whose returns are inextricably linked to shared market movements. This approach provides a more theoretically grounded and realistic lens for analyzing this specific context than one based on historical performance. Nonetheless, for the purpose of completeness and to ensure the robustness of the findings, an analysis based on historical aspiration levels is also conducted in the robustness checks subsection.

2.3. Underperforming Social Aspirations

This study develops separate hypotheses for each situation, proposing that the investor’s response fundamentally differs depending on whether performance falls below or exceeds the social aspiration level. This asymmetric response is shaped by the interaction among behavioral, psychological, and institutional pressures. This subsection focuses on developing the hypothesis for the case of underperformance.

The behavioral theory of the firm predicts that when performance falls below the social aspiration level, organizations will initiate a problemistic search for solutions (Cyert & March, 1963). This search for novel strategies to close the performance gap often leads to increased risk-taking (Greve, 2003b). This tendency toward greater risk-taking in the face of shortfalls finds psychological support in prospect theory (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979). According to this theory, a social aspiration level acts as a critical reference point, similar to that in the value function. Performance below this point falls into the “domain of losses,” where decision-makers tend to seek risks to recoup their losses. Thus, prospect theory provides the psychological microfoundations for the risk-seeking behavior associated with problemistic search, reinforcing this study’s central argument.

However, the threat-rigidity thesis offers an alternative perspective, suggesting that organizations respond to performance shortfalls perceived as survival threats not with risk-taking, but with rigidity and conservatism (Staw et al., 1981). This rigid response involves restricting information processing, tightening controls, and conserving resources, which collectively reduce risk-taking. Some studies provide evidence consistent with this thesis, particularly for firms facing the threat of bankruptcy (Chen & Miller, 2007; Iyer & Miller, 2008). Thus, this perspective suggests that firms experiencing yield shortfalls would become conservative in their reaching for yield.

In contrast, this study argues that this logic does not apply to reaching for yield. In the Japanese life insurance industry during the late 1990s and early 2000s, several firms collapsed during a “negative-spread” crisis, where guaranteed policyholder returns exceeded available market yields. In this high-threat environment, yield shortfalls directed managerial attention not toward defensive retrenchment, but toward aggressively increasing portfolio yields. This response aligns with the risk-seeking behavior predicted by problemistic search theory, rather than the conservatism suggested by the threat-rigidity thesis.

For these fiduciaries, underperforming relative to peers exposes them to stakeholder criticism for missed opportunities and raises concerns about managerial competence. This pressure can motivate a proactive, problem-solving response. Therefore, consistent with the logic of problemistic search, a larger negative gap relative to the social aspiration level is expected to motivate a more aggressive reach for yield. This reasoning leads to the first hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1.

The more an income-oriented investor’s yield underperforms their social aspiration level, the higher the yield will reach in the following period.

2.4. Outperforming Social Aspirations

The behavioral response to outperformance can be understood through two distinct theoretical logics. The classic behavioral perspective suggests that firms outperforming their aspirations tend to engage in satisficing, exhibiting inertia and avoiding changes to their successful strategies (Greve, 1998; Simon, 1955). From this viewpoint, one might expect no significant change in yield after outperformance.

However, this study proposes a logic of active risk reduction, which is grounded in the pressures to maintain legitimacy and fulfill fiduciary duties. This logic draws from both institutional and agency theories. From an institutional theory perspective, significant outperformance can threaten a firm’s legitimacy by signaling a deviation from industry norms of prudent risk management. Such a deviation may attract unwelcome scrutiny from regulators and stakeholders, who can perceive it as excessive risk-taking (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). This aligns with an agency theory view, in which managers (agents) are incentivized to signal their commitment to fiduciary duties to principals (policyholders). In this context, reinforcing their identity as prudent and reliable stewards becomes paramount for managers, and this often takes precedence over maximizing financial returns.

Therefore, rather than exhibiting satisficing inertia, managers are motivated to deliberately reduce risk to reconverge with the social aspiration level, which functions as an institutionally sanctioned benchmark for prudent behavior. Such a risk-reducing move is likely to face little internal resistance and gain swift approval, as it aligns with the conservative imperatives of the organization’s senior management (Greve, 2003a). This corrective action suggests that the greater the outperformance, the more visible the deviation from the norm—and thus, the stronger the pressure for a downward yield adjustment. This logic is also consistent with prospect theory, which suggests that decision-makers in the “domain of gains” tend to become risk-averse to preserve their favorable position (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979). This strategic risk reduction mirrors behaviors observed in other financial contexts, in which high-performing fund managers have been shown to reduce risk to “lock in” their lead over competitors (Chevalier & Ellison, 1997). This reasoning leads to the second hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2.

The more an income-oriented investor’s yield outperforms their social aspiration level, the lower the yield will reach in the following period.

2.5. Underperforming Versus Outperforming

Furthermore, the magnitude of the hypothesized effects on investment yields may differ depending on whether the yield is above or below the social aspiration level. This asymmetry derives from the fundamentally risk-averse nature of the life insurance industry. As fiduciaries managing long-term obligations to policyholders, these firms operate within strict legal and regulatory frameworks designed to ensure solvency and stability (Ellul et al., 2011). This institutional context creates a strong bias against risk-taking.

Within such a risk-averse environment, the internal decision-making dynamics for addressing underperformance versus outperformance are likely to differ starkly. A proposal to reduce yield after a period of outperformance—effectively a decision to reduce risk and realign with industry norms—is likely to be viewed as a prudent, conservative action. Such a move would face little internal resistance and likely gain swift approval from senior management and boards of directors, who are accountable for the firm’s long-term stability (Greve, 2003b).

By contrast, a proposal to significantly increase yield after underperforming—an act of problemistic search that entails taking on more risk—would likely trigger more intense debate and face greater organizational hurdles. While motivated by the need to close a performance gap, such a strategy conflicts with the institution’s core imperative to limit risk. This risk-averse posture, as Greve (2003b) notes, reinforces organizational inertia and creates political constraints within decision-making processes. Because arguments for reducing risk face fewer organizational barriers than those for increasing risk, the behavioral adjustment following outperformance is expected to be stronger and more pronounced than the problem-solving response following underperformance. This logic leads to the third hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3.

The negative relationship between an income-oriented investor’s yield relative to their social aspiration level and the yield in the following period is stronger when the investor outperforms their aspiration level than when they underperform.

2.6. Moderating Roles of Organizational Slack

This subsection builds on the analysis of the main effects of performance feedback by turning to a key contingency factor widely discussed in the behavioral theory of the firm: organizational slack. Organizational slack is a cushion of actual or potential resources that allows an organization to adapt effectively to internal pressures and external change (Bourgeois, 1981). A dominant stream of research suggests that organizational slack serves as a buffer, enabling firms to undertake riskier, problemistic search activities when performance falls below aspirations (Audia & Greve, 2006; Bromiley, 1991; Greve, 2003a, 2003b). However, this view is challenged by arguments that abundant slack may divert managerial attention away from performance gaps, thereby dampening a firm’s responsiveness (Chen & Miller, 2007). This creates a scholarly tension: does organizational slack uniformly enable risk-taking, or is its function contingent on the performance context—specifically, whether a firm is underperforming or outperforming? The finance literature on insurance companies adds another layer of complexity. It suggests that regulatory capital constraints—a concept related to but distinct from organizational slack—can compel firms with less of a financial buffer to take more risk (Ellul et al., 2011; Becker & Ivashina, 2015).

To resolve this scholarly debate, this study posits that the function of organizational slack is contingent on a firm’s performance relative to their aspiration level. Accordingly, to explicitly test these contingent roles, separate hypotheses are developed for the contexts of underperformance and overperformance.

When a firm is underperforming, it confronts a problem that necessitates a search for solutions. In the context of this study, this problemistic search manifests as seeking higher yields, which entails taking on more risk. Under this scenario, organizational slack is theorized to act as a crucial resource buffer. It provides the financial cushion necessary to absorb potential short-term losses from new, riskier investments, thereby enabling and emboldening problemistic search. For an income-oriented investor, this search translates into a greater willingness to invest in higher-risk assets to close the performance gap. Therefore, the expected negative relationship between underperformance and following increases in yield should be stronger for investors with more organizational slack. This logic leads to Hypothesis 4a:

Hypothesis 4a.

When an income-oriented investor underperforms their social aspiration level, higher organizational slack strengthens the negative relationship between the investor’s yield relative to that level and the yield they reach in the following period.

Conversely, organizational slack plays a distinct role when an income-oriented investor outperforms their social aspiration level. As argued for Hypothesis 2, outperforming industry peers creates pressure on investors to reduce risk. To avoid being perceived as reckless and to signal prudent stewardship, such investors may lower their investment yields.

However, abundant organizational slack can counteract this effect. Slack resources, such as ample solvency, equity capital, and access to financing, act as a buffer. This buffer insulates an income-oriented investor from the external pressure to conform that arises from outperforming peers. An income-oriented investor with substantial organizational slack can absorb potential short-term losses without facing an immediate crisis. This financial flexibility reduces the perceived urgency to align their risk profile with the industry average. Such insulation can foster organizational inertia and complacency, reducing the pressure on managers to make corrective, risk-reducing adjustments to their investment yields. In essence, organizational slack dampens the income-oriented investor’s responsiveness to social performance feedback. Consequently, the corrective pressure to reduce investment yield—a pressure that is strong for a high-performing, low-slack investor—is significantly weaker for an investor with abundant organizational slack. This logic leads to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4b.

When an income-oriented investor outperforms their social aspiration level, higher organizational slack weakens the negative relationship between the investor’s yield relative to that level and the yield they reach in the following period.

2.7. Moderating Roles of Portfolio Slack

Unlike the general buffer provided by organizational slack, investment decisions require a more specific resource: portfolio slack. This study conceptualizes portfolio slack as a psychological signal to managers about the portfolio’s capacity to absorb risk, directly influencing managerial risk-taking in asset allocation. This study operationalizes portfolio slack as the unrealized gains and losses within an investment portfolio. For example, studies in the banking industry have noted that unrealized gains can provide liquidity when realized, while unrealized losses can constrain lending or force asset sales (W. B. Marsh & Laliberte, 2023). Consistent with the logic for Hypotheses 4a and 4b regarding organizational slack, this study hypothesizes that portfolio slack has distinct moderating effects depending on whether a firm is underperforming or outperforming.

When an income-oriented investor underperforms their social aspiration level, they engage in a problemistic search for higher-yield solutions, a process that entails increased risk-taking. In this context, high portfolio slack—in the form of unrealized gains—strengthens this problemistic search by serving as both a financial cushion to absorb potential losses from riskier investments and a psychological signal of the portfolio’s resilience. This financial and psychological buffer makes a strategic shift toward higher-yield assets seem more manageable and less risky.

Conversely, an investor with low portfolio slack—characterized by unrealized losses—lacks this crucial buffer. The resulting financial and psychological constraints inhibit a search for higher-risk solutions. Therefore, the extent to which an underperforming investor translates their problemistic search into actual risk-taking is contingent upon the availability of portfolio slack. Thus, a larger buffer of unrealized gains is expected to strengthen the negative relationship between underperformance and following yield increases. This logic leads to Hypothesis 5a:

Hypothesis 5a.

When an income-oriented investor underperforms their social aspiration level, higher portfolio slack strengthens the negative relationship between the investor’s yield relative to that level and the yield they reach in the following period.

By contrast, when an investor outperforms their peers, their primary motivation may shift toward risk reduction to realign with industry norms, as previously argued for Hypothesis 2. Portfolio slack is expected to weaken this corrective, risk-averse behavior. A substantial cushion of unrealized gains can instill a sense of security, which in turn reduces managers’ perception of immediate threats from market volatility. This sense of security may lower the perceived urgency to reduce yields to the social aspiration level. The investor becomes more accepting of their outperforming, higher-risk position. Conversely, an investor with a smaller cushion of unrealized gains or facing unrealized losses will likely be more sensitive to potential market downturns and thus more motivated to lower the portfolio’s risk by reducing their yield. Therefore, greater portfolio slack dampens the risk-reducing response that follows outperformance. This reasoning leads to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 5b.

When an income-oriented investor outperforms their social aspiration level, higher portfolio slack weakens the negative relationship between the investor’s yield relative to that level and the yield they reach in the following period.

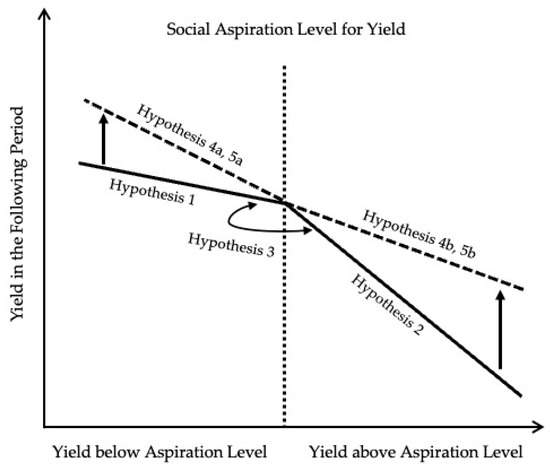

Figure 1 depicts how underperformance and outperformance relative to the social aspiration level influence yield in the following period, and how these relationships are moderated by organizational and portfolio slack.

Figure 1.

Yield-performance feedback and moderating effects. Note: The solid line represents the main effects (Hypotheses 1 and 2). The dashed line illustrates the moderated relationship under high organizational and portfolio slack. The vertical arrows indicate the direction of the moderating effects of slack (Hypotheses 4a, 4b, 5a, 5b), and the curved arrow indicates the comparison of the slopes (Hypothesis 3).

3. Methods

3.1. Sample

This study tests seven hypotheses with an unbalanced panel dataset of all life insurance companies operating in Japan from 2000 to 2019. The Japanese life insurance industry during this period offers an ideal setting to test the hypotheses for three reasons. First, the industry provides a suitable context for examining how social aspiration levels influence investment risk-taking. Because the investment returns of Japanese life insurance companies are primarily determined by common market factors, particularly the prevailing interest rate environment, peer performance emerges as a salient benchmark for success. This shared exposure makes the setting well suited for investigating performance feedback relative to social aspirations.

Second, the study period provides a unique context for observing investor behavior under extreme economic pressure. The sample period (2000–2019) begins shortly after the introduction of the Zero-Interest-Rate Policy in 1999, and encompasses the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and the launch of QQE in 2013. This prolonged low-interest-rate environment placed intense pressure on life insurance companies, compelling them to reach for yield and creating a rich context for observing their behavioral responses. From 2000 to 2019, the annual average yield of the 10-year JGB consistently declined, falling from 1.71% at the start of the period to −0.09% at the end. The overall average yield was approximately 0.97%, and this downward trend accelerated sharply after 2015, culminating in the yield entering negative territory for the first time in 2016 (at −0.03%).

Third, the industry’s institutional context—characterized by conservative managerial norms and strong fiduciary obligations—offers a compelling setting to examine risk-taking behaviors that may differ from those observed in more aggressive sectors, such as mutual funds. These norms reflect a management culture that traditionally prioritizes stability and failure avoidance over profit maximization. The conservative orientation is further reinforced by fiduciary obligations—a legal and ethical duty to manage policyholders’ assets prudently. The central mission is to preserve capital and maintain long-term solvency to meet future payout obligations. These factors create a strong institutional pressure against high-risk strategies.

The final dataset comprises 735 firm-year observations for 76 companies and reflects merger and acquisition (M&A) activity, market entries, and exits during the observation period. Data on life insurance companies were obtained from the annual publication Statistics of Life Insurance Business in Japan, issued by Hoken Kenkyujo Ltd. Because this source was not available electronically, the data were manually digitized by the author. Data on JGB interest rates were obtained from publications by Japan’s Ministry of Finance.

3.2. Variables

The study uses the Hardy-method, which defines yield as income gains divided by the average assets held during the period. The dependent variable, Following Change in Yield, is defined as the Hardy-method yield in year t + 1 minus the Hardy-method yield in year t. This yield metric reflects the income-oriented investment performance of life insurance companies by capturing interest, dividends, and trust income relative to the average assets utilized. It excludes unrealized gains and losses, thereby focusing on stable, recurring income components rather than volatile market valuations. This approach is particularly suitable for evaluating the behavior of income-oriented institutional investors, such as life insurance companies, whose strategic objective is to secure consistent cash flows rather than pursue capital gains.

The independent variables Underperform in Year t and Outperform in Year t are spline functions calculated by subtracting the social aspiration level in year t from the Hardy-method yield in year t (L. C. Marsh & Cormier, 2001). As in prior research based on the behavioral theory of the firm, the social aspiration level was defined as the average yield of all life insurance companies excluding the focal firm. The independent variables can be expressed by the following formula:

This study introduced two moderating variables in year t: Organizational Slack and Portfolio Slack. Organizational Slack was measured as the logarithm of the solvency margin ratio, a key indicator of insurance companies’ financial soundness. The solvency margin ratio, publicly disclosed to regulators and policyholders, reflects an insurance companies’ capacity to absorb operational losses. To address the wide dispersion in solvency margin ratios across firms and to facilitate within-firm estimation in the model described below, this study transformed the solvency margin ratio by taking its natural logarithm. This transformation reduces the influence of extreme values and enables more interpretable coefficient estimates in terms of percentage changes. Portfolio Slack was calculated by taking the percentage of unrealized gains or losses relative to book value.

Following the behavioral theory of the firm, the model for year t includes the following firm-level control variables in year t: Firm Size, Profitability, and Firm Age. Firm Size is defined as the logarithm of premiums, which is considered a suitable measure of firm size in the insurance industry (Greve, 2008). This study controlled for firm size because it can influence risk-taking in competing ways. On the one hand, larger firms may be more inclined to take risks owing to their greater capacity to absorb potential losses (Audia & Greve, 2006). On the other hand, smaller firms may also tend to take risks to pursue growth (Greve, 2008). Profitability was calculated as ordinary profit divided by premiums. This profit measure, commonly used in Japanese accounting, reflects profit generated from regular business activities before taxes and extraordinary items. Consistent with performance feedback theory, high profitability can lead to satisficing, which in turn reduces the impetus for search and change (Bromiley, 1991; Greve, 1998). Firm Age was measured as the natural logarithm of years since establishment plus one. Firm age was included as a control because older firms are more likely to possess established routines that create inertia, whereas younger firms may exhibit greater strategic flexibility (Hannan & Freeman, 1984).

Japanese government bonds are the primary investment vehicle for life insurance companies in Japan. Therefore, to control for interest rate fluctuations, the model also includes the average yields for year t of 3-, 10-, 20-, and 30-Year Bonds. These government bond yields represent the baseline for low-risk investment returns and were controlled for because prevailing interest rates in the broader market environment affect investment opportunities for insurance companies and their propensity to reach for yield in riskier asset classes (Becker & Ivashina, 2015).

Finally, Year Dummies were included to control for time-variant, industry-wide effects, such as macroeconomic shocks that affect all firms each year. While these dummy variables capture annual shifts, it is important to note that they might not fully account for the effects of gradual but significant regulatory changes. For instance, during the sample period, the Financial Services Agency began a long-term transition towards more risk-based, economic value-based solvency (EVS) regulations. Such anticipated regulatory shifts could influence investment behavior in ways not perfectly captured by year fixed effects alone.

This study has limitations regarding potential omitted variables. A key factor influencing the investment decisions of life insurance companies is their liability structure, particularly liability duration. A comprehensive model would ideally control for this, as asset-liability management (ALM) is central to insurance firms’ strategy. However, data on liability duration are not included in the annual disclosure reports, making it infeasible to include this variable in the analysis.

3.3. Model

A fixed effects model was employed to control for time-invariant firm-specific characteristics, such as corporate culture. This model captures within-firm effects over time (Allison, 2009). Given that the observations for the same firm across different years are likely not independent, this study employed robust standard errors clustered at the firm level in all analyses. This approach corrects for the potential intra-group correlation of errors, providing more reliable statistical inferences (Petersen, 2008; Cameron & Miller, 2015).

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics and correlations. While many correlations were low to moderate, high correlations were observed among the bond variables. To address potential multicollinearity issues arising from these high correlations, only the 10-Year Bond variable was included in the following regression analysis; the 3-Year, 20-Year, and 30-Year Bond variables were excluded. Although moderate multicollinearity can increase standard errors, potentially leading to less efficient parameter estimates, it does not introduce bias in parameter estimation (Cohen & Cohen, 1983). To confirm that multicollinearity was adequately mitigated after removing these variables, variance inflation factors (VIFs) were calculated using an ordinary least squares (OLS) regression with the model. The resulting mean VIF was 1.72. This value is considerably below the conventional threshold of 10 used for evaluating multicollinearity (Wooldridge, 2013).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and correlations a.

4.2. Regression Results

Table 2 reports the results of the fixed effects regression analyses predicting following change in yield. Model 1 serves as the baseline model and only includes the control variables. Model 2 introduces the two main independent variables—Underperform and Outperform—to examine Hypotheses 1–3. Building on Model 2, Model 3 incorporates the interaction terms between Organizational Slack and the independent variables to test Hypotheses 4a and 4b. Model 4 similarly adds the interaction terms between Portfolio Slack and the independent variables to assess Hypotheses 5a and 5b. Finally, Model 5 presents the fully specified model, which incorporates all variables simultaneously to robustly test Hypotheses 4a, 4b, 5a, and 5b in a single model. Except for the baseline Model 1, the following models demonstrate a good fit to the data, as indicated by within R-squared. Moreover, the inclusion of each new set of variables significantly enhances the model fit relative to the preceding model, indicating the incremental explanatory power of the included independent variables and interaction terms.

Table 2.

Fixed-effects model estimates for following yields.

Hypothesis 1 proposes that the greater an income-oriented investor’s yield underperformance relative to their social aspiration level, the larger the following increase in the investor’s yield. The results of Model 2 provide some support for this hypothesis, as indicated by the negative and marginally statistically significant coefficient for Underperform (β = −0.206, p < 0.1). Given that this variable captures the extent to which yield falls below the social aspiration level (where negative values signify greater underperformance), the negative coefficient suggests that poorer relative performance prompts a more substantial following increase in yield.

Hypothesis 2 proposes that the greater an income-oriented investor’s yield outperformance relative to their social aspiration level, the larger the following decrease in the investor’s yield. Similarly, Model 2 provides support for Hypothesis 2, revealing a negative and statistically significant coefficient for Outperform (β = −0.713, p < 0.01). This finding suggests that higher levels of yield relative to the social aspiration level tend to precede a greater following reduction in yield.

Hypothesis 3 posits that the negative effect of an income-oriented investor’s yield relative to their social aspiration level on following yield is stronger when the investor outperforms the aspiration level than when they underperform. To test this hypothesis, this study performed a Wald test comparing the coefficients for Underperform (β = −0.206 in Model 2) and Outperform (β = −0.713 in Model 2) using robust standard errors clustered by firm. Contrary to the hypothesis, the results indicate no statistically significant difference between the two coefficients (F(1,75) = 2.44, p = 0.122). Therefore, Hypothesis 3 is not supported.

Hypothesis 4a suggests that when an income-oriented investor underperforms their social aspiration level, higher organizational slack strengthens the negative relationship between this underperformance and the following yield. However, the results do not support this hypothesis. As shown in Table 2, the coefficient for the Underperform × Organizational Slack interaction term is not statistically significant in either Model 3 (β = −0.056, p > 0.10) or Model 5 (β = −0.056, p > 0.10), the full model. Therefore, the current analysis does not provide statistically significant evidence that organizational slack moderates the effect of underperformance on following yield.

Hypothesis 4b proposes that when an income-oriented investor outperforms their social aspiration level, higher organizational slack weakens the negative relationship between this outperformance and the following yield. Contrary to the lack of support for Hypothesis 4a, the analysis provides some evidence for an interaction effect between outperformance and organizational slack. The coefficient for the Outperform × Organizational Slack interaction term is positive and marginally significant in both Model 3 (β = 0.270, p < 0.1) and Model 5 (β = 0.189, p < 0.1). This indicates that organizational slack moderates the effect of outperformance on following yield. The positive sign suggests that higher organizational slack attenuates the negative effect of outperformance, which aligns with the weakening effect proposed in Hypothesis 4b. Thus, Hypothesis 4b receives marginal support.

Hypothesis 5a proposes that when an income-oriented investor underperforms their social aspiration level, higher portfolio slack strengthens the negative relationship between this underperformance and the following yield. The analysis reveals a significant interaction between underperformance and portfolio slack, supporting this hypothesis. In Model 4, the Underperform × Portfolio Slack coefficient is negative and highly statistically significant (β = −0.889, p < 0.01). This significance is maintained in the full model (Model 5), where the coefficient is similar (β = −0.764, p < 0.01). These results provide robust evidence for a significant negative interaction effect between underperformance and portfolio slack.

Hypothesis 5b proposes that when an income-oriented investor outperforms their social aspiration level, higher portfolio slack weakens the negative relationship between this outperformance and the following yield. The results show a significant positive interaction effect between outperformance and portfolio slack, supporting this hypothesis. The Outperform × Portfolio Slack interaction term is positive and statistically significant in Model 4 (β = 1.816, p < 0.05). This result holds in the full specification, Model 5 (β = 1.647, p < 0.05). This finding indicates that higher portfolio slack significantly attenuates the negative effect of outperformance on following yield, consistent with Hypothesis 5b.

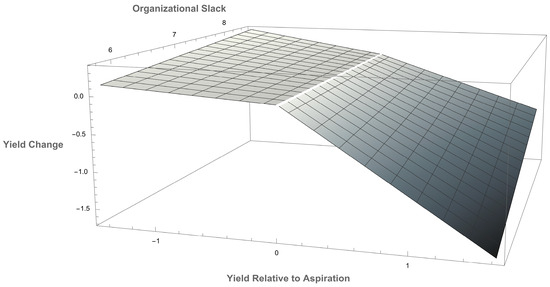

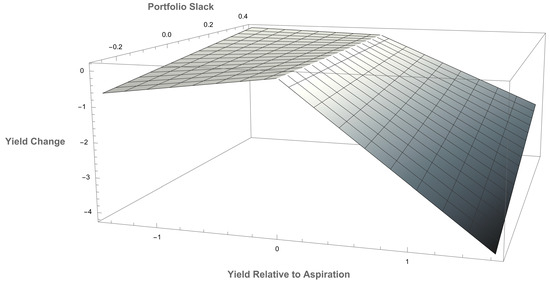

Three-dimensional plots were generated to visually interpret the significant interaction effects estimated in the full model (Model 5). Figure 2 illustrates the moderating effect of Organizational Slack on the relationship between performance relative to aspirations (Underperform and Outperform) and the predicted Yield Change. It is important to note, however, that the interaction term for Underperform × Organizational Slack was not statistically significant, while the term for Outperform × Organizational Slack was significant at p < 0.1, as shown in Table 2. Figure 3 similarly depicts the moderating effect of Portfolio Slack. Both plots show the predicted Yield Change for values ranging from two standard deviations below to two standard deviations above the means of the respective moderating variables. These figures visually demonstrate how the relationship between performance relative to aspirations and following yield change varies depending on the level of organizational or portfolio slack.

Figure 2.

Three-dimensional plot depicting interaction between organizational slack and yield relative to aspiration. Note: The interaction effect for underperformance (yield relative to aspiration < 0) is not statistically significant.

Figure 3.

Three-dimensional plot depicting interaction between portfolio slack and yield relative to aspiration.

4.3. Robustness Checks and Additional Analyses

To test the robustness of the main findings, this study conducted a series of supplementary analyses. Specifically, the robustness of the proposed theory was assessed from four distinct perspectives: (1) using an alternative definition of aspiration level, namely historical aspiration level; (2) examining the temporal structure of the effects; (3) analyzing the underlying action of asset allocation instead of the performance outcome; and (4) accounting for a major structural break in the macroeconomic environment, the 2008 GFC. Additionally, the direct effects of the two slack resources on yield-seeking and the moderating effect of firm size on performance feedback were analyzed.

First, the analysis was replicated using historical aspiration levels (a firm’s prior-year yield) instead of social aspiration levels. While much of the prior research based on the behavioral theory of the firm defines historical aspiration levels using multi-year performance trends, this approach may be less appropriate in the context of the investment activities of Japanese life insurance companies. Unlike typical manufacturing or service firms, the investment performance of these insurance companies is highly sensitive to annual market conditions. Therefore, the previous year’s yield (t – 1) serves as a more cognitively salient and contextually relevant benchmark for managerial decision-making. The results, presented in Table 3, show that the behavioral responses to Outperform are highly robust. Consistent with the main analysis, firms significantly reduce their yield after exceeding historical aspirations (supporting Hypothesis 2), and this effect is positively moderated by Organizational Slack (supporting Hypothesis 4b). By contrast, the findings related to Underperform are contingent on the aspiration type; the main effect for Underperform (Hypothesis 1) and the moderating effects of Portfolio Slack (Hypotheses 5a and 5b) become non-significant. This suggests that in this context, problemistic search is not driven by a failure to meet self-referential goals, but rather by a failure to meet goals derived from social comparison.

Table 3.

Robustness check: fixed-effects model estimates using historical aspiration.

Second, the temporal structure of the observed effects was examined through two alternative lag specifications. A model using a cumulative two-year change in yield (t to t + 2) as the dependent variable showed that the main effects of both Underperform (β = −0.626, p < 0.01) and Outperform (β = −0.620, p < 0.01) remained negative and highly significant. Another analysis of the delayed effects (i.e., the effect of performance at year t on the yield change between t + 1 and t + 2) revealed a temporal asymmetry. The yield reduction following outperformance occurs primarily in the first year (t + 1) and then dissipates (for the change between t + 1 and t + 2, β = 0.113, p > 0.10), while the response to underperformance was more delayed, persisting into the following year (t + 2) (β = −0.338, p < 0.01). This suggests that while the yield reduction after outperformance is immediate, the yield increase after underperformance is a more time-consuming process.

Third, this study tested whether the proposed theory predicts not only the performance outcome (yield) but also the underlying action of asset allocation. The analysis was replicated using changes in the proportions of (1) domestic stocks, (2) foreign securities, and (3) their combined total as alternative dependent variables. However, the results from these analyses do not lend additional support to the main findings, as neither Underperform nor Outperforme has a statistically significant effect. The null result for foreign securities, in particular, is likely attributable to their ambiguous risk profile. This asset class is a complex amalgam of low-risk foreign bonds (predominantly U.S. treasuries) with or without currency hedging, and high-risk equities. The possibility of within-portfolio adjustments is discussed in the following Discussion Section.

Fourth, the stability of the findings was tested across the major structural break of the 2008 GFC (2000–2007 and 2008–2019). The results from a model including interaction terms with a post-crisis dummy variable indicate that the core behavioral mechanisms remain robust. The fundamental responses to underperformance and outperformance are consistent across both periods. However, the analysis reveals that the positive moderating effect of Organizational Slack on the response to Outperform becames statistically insignificant in the post-crisis period. This suggests that in a severely adverse macroeconomic environment, the discretion to relax conservative behavior diminishes, even after outperforming.

Fifth, this study examined the direct effects of the two slack resources on yield-seeking. To test these effects, Organizational Slack and Portfolio Slack were added to Model 1 (the baseline model) and Model 2 (the model containing the main independent variables). In the baseline model, the coefficient for Organizational Slack was negative but not statistically significant (β = −0.043, p > 0.10), while Portfolio Slack had a significant negative effect (β = −0.093, p < 0.05). However, in Model 2, which controlled for performance feedback, the coefficients for both Organizational Slack (β = −0.059, p > 0.10) and Portfolio Slack (β = −0.003, p > 0.10) were not statistically significant. The results of this analysis provided no clear evidence that Organizational Slack and Portfolio Slack directly affect yield-seeking.

Finally, an additional analysis tests whether Firm Size moderates the behavioral responses to performance feedback. Although Firm Size and Organizational Slack are often confounded in the literature, a clear distinction between the two concepts is essential. Table 1 shows that Firm Size and Organizational Slack are negatively correlated in this sample. While large firms’ organizational inertia, rooted in complex decision-making processes, may weaken their strategic responses (Hannan & Freeman, 1984), their high social visibility may, on the other hand, induce stronger reactions as scrutiny from regulators and stakeholders exerts pressure to conform to industry norms (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). The results show that neither the Underperform × Firm Size nor the Outperform × Firm Size interaction is statistically significant, with both coefficients being positive. While this result does not prove the absence of any size effect, the lack of a strong, detectable moderator suggests that the behavioral mechanisms identified in the main analysis are influential across firms of different sizes.

5. Discussion

5.1. Main Effects of Performance Feedback

This study developed a behavioral theory of income-oriented investors, proposing a framework that explains how performance feedback relative to social aspiration levels influences following yield-seeking behavior. This theoretical framework is empirically tested in the context of Japanese life insurance companies. The findings largely support the theory’s core tenets, demonstrating that these investors adjust their investment yields based on social comparisons. Specifically, when underperforming the social aspiration level, companies increase their following yields. This response to underperformance aligns with the established mechanism of problemistic search (Audia & Greve, 2006; Posen et al., 2018), which is likely motivated by concerns about missed opportunities and stakeholder criticism.

The observed response to outperformance, however, reveals a behavior that extends beyond the traditional concept of satisficing (Cyert & March, 1963; Greve, 1998). Rather than promoting inertia, outperformance appears to trigger concerns about excessive risk-taking. In this conservative industry, significantly outperforming the social benchmark can be perceived as a deviation from prudent management, prompting a deliberate shift toward lower-yield, lower-risk positions to realign with industry norms.

This study’s analysis does not support the hypothesis that the response to outperformance would be greater in magnitude than that to underperformance. On the other hand, a robustness check reveals a temporal asymmetry that clarifies this result: the risk-reducing actions of outperforming companies are immediate, whereas the problemistic search triggered by underperformance is a more gradual process with delayed effects.

5.2. Moderating and Direct Effects of Slack Resources

The moderating role of organizational slack yields context-dependent results, affecting the response to outperformance but not to underperformance. This asymmetry suggests that the function and utility of slack depend on a firm’s performance relative to their peers. For outperforming firms, higher organizational slack dampens the tendency to reduce risk exposure. For conservative, fiduciary institutions such as insurance companies, substantial outperformance can be perceived as a potential threat. It may signal excessive risk-taking, prompting a corrective, risk-reducing response to realign with industry norms. In this context, high organizational slack, as measured by the solvency margin ratio, functions as a psychological buffer. This financial cushion likely reduces managerial anxiety about the firm’s risk profile, lowering the perceived urgency for corrective action. While theory suggests organizational slack should enable problemistic search during underperformance (Audia & Greve, 2006; Bromiley, 1991), this moderating effect was not observed. The results suggest that organizational slack does not facilitate risk-taking when a firm underperforms. In this context, where conservatism and risk aversion dominate, the solvency margin may be viewed not as a resource to be deployed for risky initiatives but rather as a defensive reserve to be safeguarded.

Portfolio slack, which represents the unrealized gains or losses within the investment portfolio itself (a distinct construct introduced in this study), demonstrated significant moderating effects in both scenarios, consistent with the theorized mechanisms. Higher portfolio slack strengthened the tendency to increase yields after underperformance, supporting the notion that ample slack acts as a buffer, making potential losses from riskier investments seem more manageable and facilitating problemistic search toward higher-yield assets (Greve, 2003a). Conversely, higher portfolio slack weakened the tendency to decrease yields after outperformance, as the buffer from unrealized gains insulates the investor from pressure to conform to peer norms and reduces the perceived urgency to make corrective, risk-reducing adjustments (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983).

In contrast to this study, prior finance literature suggests a more direct link between resource availability and risk-taking. For instance, Becker and Ivashina (2015) found that insurance companies facing tighter regulatory capital constraints—a state of diminished slack—were more inclined to reach for yield, implying a direct negative relationship whereby less slack prompts greater yield-seeking behavior. However, the additional analyses in this study find no compelling evidence that organizational and portfolio slack have a direct effect on such risk-taking.

5.3. Implications from Robustness Checks

A robustness check using historical aspiration level not only confirms the main findings but also reveals the boundary conditions of the behavioral mechanisms at play. This analysis shows that problemistic search is a distinct social phenomenon. Firms increase their yield when underperforming peers but not their own past results, empirically supporting social comparison as a primary driver of performance evaluation in asset management. For these institutions, falling behind competitors is a more urgent problem than a year-over-year decline, which can be attributed to market conditions. This social dependence also applies to portfolio slack, as its moderating effect on risk-taking is significant only in the context of social comparison. A financial cushion influences risk-taking only when managers face pressure relative to their peers. Ultimately, these findings specify that for institutional investors, the problem in problemistic search is fundamentally social. By contrast, the robust tendency to reduce yield following outperformance, consistently moderated by organizational slack, suggests a more fundamental, baseline behavior for risk-averse fiduciaries.

Robustness checks on asset allocation clarify the theory’s scope: the identified behavioral mechanisms concern income yield management, not broad shifts in major risky asset classes. This distinction is crucial, suggesting that reaching for yield is achieved through within-portfolio adjustments—such as altering bond duration or credit quality—rather than changing allocations to stocks or foreign securities. This observation reveals a key boundary: the theory explains how institutional investors respond to yield targets, but not the specific asset shifts they use to meet them. This finding aligns with the mechanism detailed by Becker and Ivashina (2015), who find that regulatory incentives lead insurance companies to make such within-portfolio adjustments. While capital requirements guide insurance companies toward safer asset categories, the rules still create opportunities for yield-seeking. Because the capital charge is fixed within a broad regulatory category, insurance companies systematically select higher-yield, higher-risk bonds in that same category. This provides a clear example of how yield-seeking behavior manifests not as a shift between major asset classes, but as a subtle selection of riskier assets within a defined regulatory bucket.

The stability of the primary performance feedback mechanisms before and after the 2008 GFC lends considerable support to the robustness of the core theory of this study. However, the finding that the moderating role of organizational slack changed in the post-crisis period offers an important insight into its contingent nature. Before the crisis, high organizational slack allowed outperforming firms to tolerate higher-risk positions, consistent with its role as a buffer that insulated firms from the pressure to conform to peer norms and reduced the perceived urgency of corrective action. The disappearance of this effect after the crisis suggests a systemic shift in risk perception within the industry. In the heightened risk-averse and stringent regulatory environment that followed the financial crisis, organizational slack might have been reframed from a resource enabling risk tolerance to a critical buffer for survival. Consequently, even firms with abundant slack might have become more uniformly prudent, reducing their yield to realign with peers when outperforming, regardless of their financial cushion.

5.4. Contributions

This study develops an integrated framework to explain the behavior of income-oriented firms, making theoretical contributions by synthesizing insights from the behavioral theory of the firm with institutional, prospect, and agency theories. First, this study extends the behavioral theory of the firm by demonstrating how its core concepts are profoundly shaped by the institutional context. It shows that for income-oriented firms, the social aspiration level (i.e., the peer average) functions not just as a performance benchmark but as a powerful industry norm that confers legitimacy. This reframes the firm’s response to performance feedback as legitimacy-seeking behavior. Specifically, the analysis identifies a key strategy in this context: deliberate risk reduction following outperformance. This behavior is not merely about maintaining the status quo but is a proactive effort to signal fiduciary prudence, thereby broadening the theory’s application beyond traditional firms.

Second, this research advances the slack literature by introducing and empirically validating the novel concept of “portfolio slack.” This study defines portfolio slack as a liquid buffer found in a firm’s unrealized portfolio gains or losses. By demonstrating this new construct’s direct influence on managerial risk perception, the study highlights the need to disaggregate slack resources and consider their proximity to the specific decision-making context.

To clarify these theoretical contributions, this subsection positions the study’s central finding—that high-performing firms become more risk-averse—within the broader literature. This finding aligns with classic tournament theory literature on U.S. mutual funds, in which studies find that “winners” who outperform their peers have an incentive to reduce risk to preserve their lead. For instance, Brown et al. (1996) noted that interim winners may scale back risk to “lock in” their end-of-year ranking, while Chevalier and Ellison (1997) suggest that funds ahead of the market are motivated to align their portfolios more closely with the market benchmark, thereby securing their gains.

However, this risk-averse behavior is not universal, a point that underscores the critical role of institutional context. Choi and Kronlund (2018), for example, find that top-performing corporate bond funds may increase their reaching for yield. They attribute this to the unique incentive structure of the bond market, in which severe penalties for poor performance discourage underperforming funds from taking gambles, thus giving top-performing-funds more freedom to take on added risk.

This study identifies a novel behavioral mechanism through which institutional norms can lead firms to act contrary to prevailing macroeconomic incentives. This study makes its contribution by analyzing a unique context: Japanese life insurance companies during the 2000–2019 period, a time characterized by the Bank of Japan’s QQE policy. This policy created strong, market-wide pressure, driving insurance companies to secure high investment yields. Contrary to this powerful economic incentive, this study demonstrates that outperforming life insurance companies actively reduced their investment yields. This counter-intuitive finding suggests that the need to conform to an industry-wide norm of prudent and conservative management was a primary behavioral driver for these firms. This normative pressure prompted them to reduce risk, even when facing market pressures for higher returns. Whereas prior studies of institutional investors have emphasized financial constraints, such as regulatory capital requirements, this research identifies a distinct mechanism rooted in social comparison and legitimacy. By demonstrating that adherence to social benchmarks can influence risk-taking, this study adds a new, micro-behavioral dimension to the understanding of institutional investor behavior, particularly within a highly regulated and conservative industry.

5.5. Practical Implications

The findings of this study offer practical implications for investment managers by transforming empirical results into data-driven strategic guidance. The proposed model provides a framework for assessing risk tolerance and informing strategic decisions. By clarifying the drivers of yield-seeking behavior, the model helps managers better understand the organizational tendencies of their own firms and those of competitors, thereby enabling more rational and deliberate strategic responses. A central insight is the critical role of portfolio slack in determining whether an underperforming firm responds with risk-averse “threat rigidity” or engages in risk-seeking “problemistic search.” Based on the full model (Table 2, Model 5), an actionable threshold can be identified. The behavioral shift occurs where the combined effect of Underperform and its interaction with Portfolio Slack equals zero. This threshold is calculated at approximately 29.7% (0.227/0.764), implying that managers of firms with unrealized gains exceeding roughly 30% of the portfolio’s book value are more likely to increase yield-seeking behavior—and thus risk—when trailing their peers. Conversely, firms below this threshold are more inclined to reduce risk. The model also clarifies responses to outperformance, showing how risk reduction is systematically moderated by both Portfolio Slack and Organizational Slack. This interaction serves as a valuable benchmark for managerial discussions, enabling a theoretically grounded understanding of how an organization’s risk appetite dynamically responds to portfolio performance.

For regulators concerned with systemic risk and financial stability, the findings suggest several actionable policy directions. First, regulators should expand their supervisory tools by incorporating behavioral indicators, such as portfolio slack, alongside traditional capital adequacy metrics (e.g., solvency margins). This study shows that portfolio slack significantly moderates risk-taking—amplifying yield-seeking following underperformance and softening risk reduction after outperformance. Sole reliance on static capital ratios may obscure firms’ actual behavioral risk profiles. A specific recommendation is to mandate more detailed disclosure on the composition of unrealized gains and losses, enhancing the transparency of this behavioral buffer.

Second, the model predicts that outperforming firms typically reduce risk and revert to the mean. Regulators can leverage this insight to identify behavioral outliers. A firm that significantly outperforms their peers, holds high portfolio slack, and fails to reduce yield may represent a behavioral anomaly requiring closer examination. Such counter-normative behavior could indicate excessive risk appetite or divergence from prudent management. A red-flag system based on this logic would enable a more proactive, risk-sensitive supervisory approach.

Finally, the study finds that yield-seeking does not necessarily occur through shifts across asset classes. Instead, risk-taking may manifest as subtler reallocations—such as moving toward longer-duration or lower-credit instruments within the same category. This suggests that regulators should intensify scrutiny within asset classes, not just across broad allocations. These findings support ongoing initiatives like the transition to EVS, which encourages more granular, risk-adjusted asset evaluation.

5.6. Limitations and Future Research

This study has several limitations that offer avenues for future research. First, this study’s focus on Japanese life insurance companies limits the generalizability of its findings. Japan’s unique institutional context—its financial environment, regulatory framework, and culture of homogeneity—likely shaped the observed risk-reducing behaviors. Generalizing these findings to companies in other countries warrants caution, as in more aggressive institutional contexts—such as U.S. mutual funds—outperformance might lead to increased risk-taking, thereby highlighting the critical role of institutional context.

Second, the analytical model has limitations. The model omits firms’ liability structures (e.g., liability duration), a critical determinant of investment decisions, because the necessary data are not publicly available. It also might not fully capture gradual regulatory shifts, such as the move toward EVS in Japan. Furthermore, the fixed-effects model might not account for endogeneity from time-varying unobserved factors, like a shift in corporate strategy. The results should be interpreted with this caveat. Future research could employ such techniques as the Generalized Method of Moments (GMM) to address this dynamic endogeneity and provide a more robust test of the causal mechanisms.

Third, this study treats portfolio slack as a single composite construct. While this aggregate measure of a manager’s perceived financial cushion proved predictively valid, future research could disentangle its components. For example, a more granular analysis could separate unrealized gains that form a true “liquidity buffer,” derived from highly liquid assets, from more volatile “paper gains” tied to less liquid assets. This would clarify whether portfolio slack functions primarily as a financial resource or as a psychological signal of safety, offering a more precise understanding of the drivers of managerial risk-taking behavior.

Fourth, the focus on the Hardy-method yield, which excludes capital gains and losses, defines a clear but narrow scope. This choice intentionally isolates the behavior of income-oriented investors that must secure stable cash flows. However, it overlooks total return objectives, including capital appreciation. Consequently, while the findings illuminate how companies adjust income-seeking behavior, they do not address strategies for managing capital gains and losses. Future research could adopt total return measures to explore how investors balance the trade-off between income generation and capital appreciation, offering a more comprehensive perspective.

6. Conclusions

This study develops and empirically tests a behavioral theory of income-oriented investors, examining how performance feedback on yield relative to social aspiration levels influences subsequent reach-for-yield behavior. Using Japanese life insurance companies from 2000 to 2019 as the research setting, the analysis finds that these investors adjust their yields based on peer comparisons: they increase yields after underperformance and decrease yields after outperformance.

The analysis further reveals the distinct moderating roles of different types of slack resources. Portfolio slack, a construct developed in this research, is a significant moderator of these yield adjustments. This form of slack intensifies the tendency to increase yields after underperformance and, conversely, attenuates the tendency to reduce yields after outperformance. By contrast, the effect of organizational slack is more limited, dampening only the yield-reducing response to outperformance.

This research makes two primary contributions to the literature. First, it proposes a behavioral theory tailored to income-oriented investors. Second, it extends research on organizational slack by introducing and demonstrating the distinct analytical importance of portfolio slack. The findings also offer practical insights for investment managers seeking to understand the behavioral patterns of their own firms and competitors, as well as for financial regulators concerned with risk-taking behavior and financial stability.

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 21K13364.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data analyzed in this study were manually digitized from 20 volumes of the Statistics of Life Insurance Business in Japan (インシュアランス生命保険統計号), covering fiscal years 1999–2018. While the publisher, Hoken Kenkyujo Ltd., has ceased operations, the original printed volumes remain accessible through selected public and university libraries in Japan. The digitized dataset supporting the findings of this study is available from the author upon reasonable request for the purpose of reproducing the analyses and verifying the results. Separately, the author welcomes inquiries regarding potential research collaborations.

Acknowledgments

The research presented in this paper is an outcome of the author’s work in the “Study Group on ESR Regulation and the Investment Practices of Life Insurance Companies,” a FY2022–FY2023 commissioned research project by the Association of Postal Life Insurance Policy-holders. I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the group members for their insightful discussions and invaluable feedback on this research. The author is also deeply indebted to the four anonymous reviewers whose sharp and constructive comments significantly improved the quality of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| VIF | Variance Inflation Factors |

| OLS | Ordinary Least Squares |

| EVS | Economic Value-Based Solvency |

| ALM | Asset-Liability Management |

| QQE | Quantitative and Qualitative Monetary Easing |

| GFC | Global Financial Crisis |

| ROA | Return on Assets |

| M&A | Mergers and Acquisitions |

| JGB | Japanese Government Bond |

| GMM | Generalized Method of Moments |

References

- Allison, P. D. (2009). Fixed effects regression models. SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Andonov, A., Bauer, R. M., & Cremers, K. M. (2017). Pension fund asset allocation and liability discount rates. The Review of Financial Studies, 30(8), 2555–2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andraszewicz, S., Kaszas, D., Zeisberger, S., & Holscher, C. (2023). The influence of upward social comparison on retail trading behaviour. Sci Rep, 13(1), 22713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Audia, P. G., & Greve, H. R. (2006). Less likely to fail: Low performance, firm size, and factory expansion in the shipbuilding industry. Management Science, 52(1), 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audia, P. G., Locke, E. A., & Smith, K. G. (2000). The paradox of success: An archival and a laboratory study of strategic persistence following radical environmental change. Academy of Management Journal, 43(5), 837–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, B., & Ivashina, V. (2015). Reaching for yield in the bond market. The Journal of Finance, 70(5), 1863–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgeois, L. J., III. (1981). On the measurement of organizational slack. Academy of Management Review, 6(1), 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromiley, P. (1991). Testing a causal model of corporate risk taking and performance. Academy of Management Journal, 34(1), 37–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K. C., Harlow, W. V., & Starks, L. T. (1996). Of tournaments and temptations: An analysis of managerial incentives in the mutual fund industry. The Journal of Finance, 51(1), 85–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, A. C., & Miller, D. L. (2015). A practitioner’s guide to cluster-robust inference. Journal of Human Resources, 50(2), 317–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W. R., & Miller, K. D. (2007). Situational and institutional determinants of firms’ R&D search intensity. Strategic Management Journal, 28(4), 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevalier, J., & Ellison, G. (1997). Risk taking by mutual funds as a response to incentives. Journal of Political Economy, 105(6), 1167–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J., & Kronlund, M. (2018). Reaching for yield in corporate bond mutual funds. The Review of Financial Studies, 31(5), 1930–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J., & Cohen, P. (1983). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). L. Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Cyert, R. M., & March, J. G. (1963). A behavioral theory of the firm. Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Di Maggio, M., & Kacperczyk, M. (2017). The unintended consequences of the zero lower bound policy. Journal of Financial Economics, 123(1), 59–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]