Abstract

With the increasing adoption of technologies such as mobile banking and blockchain, the banking sector in developing and emerging economies is experiencing both opportunities and challenges. This study examines the impact of FinTech on bank risk-taking and profitability in the small island economy of Fiji, spanning the period from 2000 to 2024. We employ a fixed-effects model and conduct robustness checks using random effects, pooled ordinary least squares (OLS), and the generalized method of moments (GMM) method, focusing on seven banks (five commercial banks and two non-bank financial institutions). Our analysis evaluates the effect of FinTech while controlling for other bank-specific factors that may influence risk-taking and profitability. The results indicate that FinTech development significantly reduces bank risk-taking and enhances profitability, suggesting a positive and substantial impact on financial performance and stability. The findings highlight the need for banks operating in Fiji and similar small economies to continue and expand their investments in FinTech innovations. Furthermore, the study suggests that regulatory bodies and policymakers should strengthen institutional and regulatory frameworks to support and guide FinTech’s evolution within the banking sector.

1. Introduction

Financial markets are undergoing substantial transformations, specifically with the emergence of financial technology (FinTech), which has disrupted conventional banking models and reshaped the dynamics of these markets (Broby, 2021; Vives, 2017). FinTech refers to the use of innovative technology to deliver financial services and products more efficiently, securely, and conveniently (Leong & Sung, 2018; Yang & Wang, 2022). While large economies have quickly adopted and integrated FinTech solutions into their financial systems, the impact of FinTech on bank performance in small developing island states, such as Fiji, remains relatively scarce. Small island economies face unique financial and economic challenges, including limited access to global capital markets, high dependence on tourism and remittances, and vulnerabilities to economic shocks (Briguglio, 1995; Read, 2004; Tang et al., 2024). As these economies increasingly adopt FinTech innovations, it is important to assess their implications for financial stability, particularly in relation to bank risk and profitability.

FinTech consists of a wide range of digital financial services, including mobile banking, digital payments, peer-to-peer (P2P) lending, blockchain applications, and artificial intelligence-driven financial solutions (Cao et al., 2021; Lyu et al., 2023). These innovations have the potential to enhance financial inclusion, reduce transaction costs, and improve efficiency in financial intermediation (Misati et al., 2024). FinTech has greatly improved bank financing efficiency by using automated tools like intelligent risk assessment systems and automated approval processes (Polireddi, 2024). These technologies speed up financing approvals, reducing both time and labor costs for banks (Kukman & Gričar, 2025; Lee et al., 2021). By helping banks assess and manage risks more accurately, FinTech lowers the number of non-performing loans, further cutting financing costs. For instance, big data analysis allows banks to better understand customers’ financial situations and credit histories, leading to more accurate financing decisions.

However, FinTech also introduces new risks, including cybersecurity threats, regulatory challenges, and increased market competition, all of which can significantly impact the risk profiles of banks operating in small developing island states (Gomber et al., 2018). One major change brought by FinTech is the transformation of time in financial transactions (Jović & Nikolić, 2022). Traditional delays in processing and settlement are being replaced by near-instantaneous transactions, both domestically and across borders. While this shift improves efficiency and user convenience, it also creates new vulnerabilities. Real-time settlement shortens the window for detecting and responding to fraudulent activities, increasing exposure to risks such as cybercrime and push payment fraud. As FinTech continues to evolve, managing these time-sensitive risks becomes a critical concern for regulators, financial institutions, and consumers alike (S. Chen & Guo, 2023).

There are several specific ways FinTech contributes to these risks. First, FinTech solutions like mobile banking apps, blockchain platforms, and online payment systems increase the number of digital endpoints, each of which can be a potential target for hackers (Smith, 2020; Uddin et al., 2020). Second, many FinTech services—particularly those related to digital payments and cryptocurrencies—operate across borders, complicating enforcement and supervision due to differing laws and regulatory standards in various countries (Lehmann, 2020). Third, FinTech firms often benefit from lower costs, greater agility, and digital-first strategies, allowing them to challenge traditional banks, especially in areas such as remittances, microloans, and mobile payments (Cumming et al., 2023). This increased market competition pressures traditional banks to adapt their business models, which can sometimes lead them to take on higher risks to stay competitive.

Fiji’s banking sector is relatively small but well-regulated, consisting primarily of commercial banks and non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs). The six licensed commercial banks operating in Fiji include Westpac Banking Corporation Limited (Sydney, Australia), Australia and New Zealand Banking Corporation Limited (ANZ, est. 1953, Melbourne, Australia), Bank of Baroda (Mumbai, India), Bank of the South Pacific Limited (Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea)1, BRED Bank Limited (Paris, France), and Home Finance Company Bank (Suva, Fiji)2. Of these, Home Finance Company is the only fully locally owned bank, with 75% of its shares held by the Fiji National Provident Fund (FNPF) and the remaining 25% by the Unit Trust of Fiji (UTOF). The remaining five banks are foreign-owned. In addition to these banks, the financial sector includes three licensed credit institutions—Merchant Finance Limited (MFL), Credit Corporation (Fiji) Limited (CCFL), and Kontiki Finance Limited (Suva, Fiji)—along with insurance providers and the FNPF. Collectively, NBFIs account for approximately 63% of the total assets in Fiji’s financial system (Reserve Bank of Fiji, 2018).

Historically, the banking sector in Fiji has faced challenges such as limited financial inclusion, heavy reliance on physical branches, and a narrow range of financial products designed for a small, geographically dispersed population (Chand et al., 2023). However, recent technological advancements have begun to reshape the financial landscape. Mobile payment platforms like Vodafone’s M-PAiSA and Digicel’s MyCash are driving change by facilitating more accessible and efficient transactional services. The integration of M-PAiSA and MyCash into Fiji’s national payment system (NPS) marks a transformative shift in the nation’s financial landscape, addressing long-standing information silos and promoting financial inclusion (Reddy, 2025). Previously, mobile wallets operated in isolation from traditional banking systems, limiting seamless financial interactions and hindering access to financial services, especially for those in remote areas. With the new integration, users can now transfer funds in near real-time between their mobile wallets and bank accounts, encompassing all major commercial banks in Fiji (Reserve Bank of Fiji, 2022). These innovations have enhanced financial inclusion and improved foreign exchange management. Recognizing the transformative potential of such technologies, the Reserve Bank of Fiji (RBF) has initiated steps to regulate and integrate them into the broader financial system. Nevertheless, the adoption of digital financial services remains incomplete, presenting both opportunities and challenges for further integration.

To ensure the soundness of the financial system, the RBF oversees both commercial banks and NBFIs, implementing several components of the Basel Capital Accord to enhance prudential regulation. These include capital adequacy requirements and comprehensive risk management frameworks. The RBF also licenses and supervises FinTech operators as part of its evolving regulatory scope. While Fiji is not a direct member of the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), it aligns with FATF standards through its membership in the Asia/Pacific Group on Money Laundering (APG) (Reserve Bank of Fiji, 2016). This alignment supports the implementation of anti-money laundering (AML) and counter-terrorism financing (CTF) measures (Reserve Bank of Fiji, 2016). Recent reforms have expanded regulatory oversight to encompass digital financial services, with a particular emphasis on Know Your Customer (KYC) protocols and transactional transparency.

Given the small size of the economy and its heavy reliance on a few key sectors, such as tourism and agriculture, the Fijian banking sector is especially vulnerable to external shocks and economic fluctuations (Dominic et al., 2023). Moreover, the relatively limited capacity of banks to diversify their portfolios and manage systemic risks makes them particularly susceptible to both domestic and international market forces. Financial technologies, while promising, have the potential to alter these risk dynamics in profound ways. Thus, understanding the relationship between FinTech adoption and banking performance in Fiji is critical to ensuring a balanced and resilient financial ecosystem.

The existing literature on Fiji’s banking sector has primarily focused on several key areas, including net interest margin (Gounder & Sharma, 2012), bank efficiency (Jayaraman et al., 2017), non-performing loans (Chand et al., 2023; R. R. Kumar et al., 2018), bank deposits (Chand et al., 2024a), bank profitability(Chand et al., 2024b), and financial stability (Chand et al., 2021). While these studies offer valuable insights into the traditional banking environment in Fiji, there remains a significant gap in the literature concerning the influence of FinTech on the country’s banking performance. As FinTech continues to reshape banking operations globally through innovations such as digital payments, mobile banking, and peer-to-peer lending, understanding its implications in a small, developing island economy like Fiji becomes critical. This study makes a pioneering contribution by being the first to empirically examine the impact of FinTech on bank risk-taking and profitability in the context of Fiji, ranging from 2000 to 2024. Utilizing a fixed effects estimator, along with robustness checks using random effects, pooled OLS, and GMM estimation techniques, the analysis provides robust and consistent evidence that FinTech adoption significantly reduces bank risk-taking while enhancing profitability. These findings offer novel insights into the role of FinTech in strengthening financial stability and performance in small island developing states (SIDS), a context that remains underexplored in the existing literature. The study not only fills a critical gap but also informs policymakers, regulators, and banking institutions in the Pacific region on the strategic importance of embracing FinTech innovations.

The rest of the study is as follows: Section 2 presents the relevant literature regarding the relationship between FinTech, bank risk-taking, and profitability. Section 3 presents the data and methodology, and Section 4 presents the results. Section 5 concludes the paper with key policy implications.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Linking FinTech and Bank Risk-Taking

Theoretically, the relationship between FinTech and bank risk-taking is nuanced, with divergent schools of thought offering competing predictions. One side of the debate—the traditional “competition-fragility” hypothesis—contends that greater competition leads to more bank risk-taking (De Nicolo et al., 2006). Specifically, more competition erodes banks’ market power and, therefore, reduces their charter value (Keeley, 1990; Marcus, 1984)3. Lower charter values diminish the consequences of failure, thereby encouraging banks to take on greater risks in pursuit of higher returns (Srivastava et al., 2023). Beyond financing riskier ventures, banks may also explore new noninterest income streams, which can further elevate their overall risk exposure (Stiroh, 2004). Similarly, a decline in charter value may weaken incentives to rigorously screen potential borrowers, leading to a deterioration in credit quality and increased overall financial fragility (Dell’Ariccia & Marquez, 2006). In extreme cases, severely distressed banks with minimal remaining equity—often due to sustained weak profitability—are more likely to engage in “gambling for resurrection” (Meckling & Jensen, 1976). Studies support this risk-shifting behavior: Beck et al. (2013) found that heightened competition increases bank fragility, particularly when regulatory activity restrictions are more stringent. Similarly, Valencia and Bolaños (2018) provided evidence that in more competitive banking markets, banks tend to hold lower capital buffers, consistent with charter value theories that link intensified competition to riskier banking behavior.

On the opposing side of the debate, the “competition-stability” hypothesis argues that increased competition can strengthen financial stability by lowering loan rates, reducing borrower credit risk, and decreasing the likelihood of bank failures (Boyd & De Nicoló, 2005). In other words, this hypothesis suggests that greater market power may lead to higher bank risk, as elevated lending rates can make it harder for borrowers to repay their loans (Liu & Zhu, 2024). This, in turn, heightens moral hazard by encouraging borrowers to engage in riskier ventures. Moreover, higher interest rates may attract riskier borrowers due to adverse selection; individuals with limited access to cheaper credit—such as those with poor credit histories—are more likely to accept costly loan terms. Additionally, reduced competition often coincides with higher bank concentration, which may foster excessive risk-taking if large institutions believe they are “too big to fail” and expect explicit or implicit government support (Stern & Feldman, 2004). Supporting evidence for this hypothesis shows that bank failure risk tends to increase in more concentrated markets (De Nicolo et al., 2006), while more competitive banking systems are generally associated with lower failure rates (Schaeck & Čihák, 2008).

Empirical studies have reported mixed results regarding the impact of FinTech on bank risk-taking. One strand of research aligns with the traditional competition-fragility hypothesis. For example, Bakker et al. (2023) found that FinTech is associated with higher risk-taking by banks in emerging and developing economies, as well as in Latin America and the Caribbean. R. Wang et al. (2021) provided robust evidence that the development of FinTech generally exacerbates banks’ risk-taking in China. Similarly, Fang et al. (2023) reported that an increase in FinTech led to higher bank risk-taking through the liquidity creation channel in China. In a recent study, X. Li (2025) also supported the finding that improvements in FinTech increase bank risk-taking in China. Using a sample of U.S. community banks, Jia (2024) found that FinTech increases bank risk-taking. Elekdag et al. (2025) found FinTech increases bank risk-taking for a global sample of 57 countries. Anestiawati et al. (2025) investigated the effect of bank FinTech on credit risk across 20 developed and 20 developing economies, revealing that FinTech leads to an increase in credit risk.

In contrast, several empirical studies have supported the competition-stability hypothesis, suggesting that advancements in FinTech contribute to reduced bank risk-taking. For instance, Banna et al. (2022) found that the development of FinTech significantly decreased the risk-taking behavior of microfinance institutions operating in Sub-Saharan Africa. Cheng and Qu (2020) examined the effect of bank FinTech on credit risk in China and found that FinTech helps lower credit risk for Chinese commercial banks. Similarly, C. Li et al. (2022) reported a negative relationship between FinTech and bank risk-taking in China. In a related study, J. Wang et al. (2023) examined the role of FinTech in managing the transfer of implicit government debt risk to Chinese commercial banks and discovered that the application of financial blockchain technology effectively limited this risk spillover. Furthermore, Kayed et al. (2025) found that FinTech innovations led to a reduction in bank risk-taking among financial institutions in Jordan. Supporting these findings, Wu and Qi (2025) observed that FinTech reduced bank risk-taking in China by enhancing credit capacity, increasing deposit volumes, and diversifying income structures. Therefore, the first hypothesis is formulated as follows:

H1.

Bank FinTech is negatively associated with bank risk-taking.

2.2. Linking FinTech and Bank Profitability

The impact of FinTech on bank profitability can be understood from the lens of disruptive innovation theory and technology spillover theory.

First, disruptive innovation theory, which is widely used in the literature to explain the impact of FinTech on bank profitability (Siek & Sutanto, 2019; Tarawneh et al., 2024), describes how new technologies or business models can fundamentally transform established industries by initially targeting overlooked or underserved market segments (Kjellman et al., 2019). These innovations typically begin with a modest market impact but, over time, improve and evolve to challenge—and eventually displace—mainstream incumbents (Leo et al., 2019; Owusu & Gupta, 2024). This theory is particularly relevant in the context of FinTech and its growing influence on the traditional banking sector (Solanki & Sujee, 2022).

FinTech companies often introduce innovative financial products and services that are more accessible, affordable, and user-centric than conventional banking offerings (Nugraha et al., 2022). Examples include mobile banking applications, peer-to-peer lending platforms, digital wallets, and blockchain-based solutions (Mothobi & Kebotsamang, 2024). These innovations tend to attract customers who feel underserved or dissatisfied with the limitations of traditional banks (T.-H. Chen, 2020). As these technologies mature and gain broader acceptance, they redefine customer expectations and disrupt long-standing competitive dynamics within the financial services industry (Bouheni et al., 2023).

Traditional banks that fail to adapt to these technological shifts risk losing relevance in a market that increasingly values speed, convenience, and personalization. In contrast, financial institutions that proactively integrate FinTech solutions can significantly enhance operational efficiency, reduce costs, and improve customer satisfaction. By leveraging digital tools and platforms, banks can also extend their reach, particularly in underserved or geographically remote areas, thereby expanding their customer base and increasing market penetration (Ibidunni et al., 2022).

In smaller and developing economies, such as Fiji, the impact of FinTech can be especially transformative. By adopting these innovations, banks in such regions can overcome structural challenges, provide inclusive financial services, and improve economic resilience. However, the failure to embrace disruptive technologies may expose these institutions to heightened competitive pressure and the risk of obsolescence.

Ultimately, disruptive innovation theory highlights the imperative for continuous innovation. For banks, especially in emerging markets, embracing FinTech is not just a strategic advantage; it is essential for long-term survival and growth in a rapidly evolving financial landscape.

Second, as financial institutions increase their investments in FinTech, the integration of technologies and financial services will be enhanced, which will accordingly reflect the technology spillover effect and improve the performance of financial institutions (Kayed et al., 2025; Von Solms, 2021). FinTech integration into traditional banking practices can significantly alleviate the time and space limitations typically associated with financial service delivery (Elsaid, 2023). By leveraging digital platforms such as the internet and mobile payments, banks can offer real-time, always-accessible financial services. This technological capability extends the reach of banking services beyond physical branches, allowing institutions to broaden their market coverage and improve operational responsiveness. As a result, banks can collect, process, and analyze data more efficiently, which can enhance customer acquisition and support their entry into the broader financial system (Gomber et al., 2018). Empirical evidence supports the transformative impact of electronic payment systems on bank performance. Studies by Adalessossi (2023) and Kharrat et al. (2024) consistently demonstrated that digital payment technologies positively affect bank profitability by streamlining transaction processes, reducing service delivery times, and improving financial transparency. FinTech practices also contribute to cost minimization in key areas. For instance, they reduce channel costs by enabling more efficient service delivery methods and optimizing service point locations (Stulz, 2019). Similarly, credit review costs are lowered through faster and more accurate customer data retrieval, improving lending decisions (C. Li et al., 2022). Collectively, these technology spillover effects not only support operational efficiencies but also play a critical role in boosting banks’ profitability and long-term sustainability.

Empirical studies regarding the impact of FinTech on bank profitability provide mixed evidence. For instance, Aloulou et al. (2024) and Kayed et al. (2025) found a positive effect, while Lu and Kosim (2022) and Adalessossi (2023) reported a negative impact. Conversely, Bouheni et al. (2023) found no significant relationship. Nevertheless, based on the above discussion, we contend that FinTech can increase bank profitability. Hence, our second hypothesis is formulated as follows:

H2.

Bank FinTech is positively associated with bank profitability.

3. Data, Variable Definition, and Method

3.1. Data

This study uses data from seven financial institutions (FIs) covering the period from 2000 to 2024, forming a balanced panel. The sample consists of five commercial banks—Australia and New Zealand Banking Group (ANZ), Bank of the South Pacific (BSP), Bank of Baroda (BOB), Westpac Banking Corporation (WBC), and Home Finance Corporation (HFC)—along with two non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs): Merchant Finance Limited (MFL) and Credit Corporation Fiji Limited (CCFL). The data used for estimation are sourced from the Reserve Bank of Fiji (2024) and the World Development Indicators (World Bank, 2024). Table 1 summarizes the dependent and independent variables used in the estimation.

Table 1.

Variable descriptions.

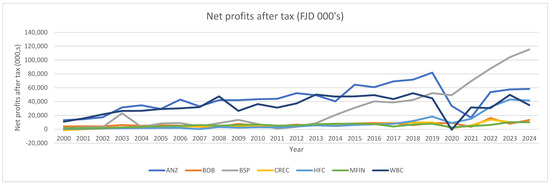

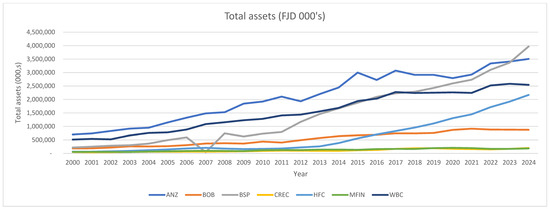

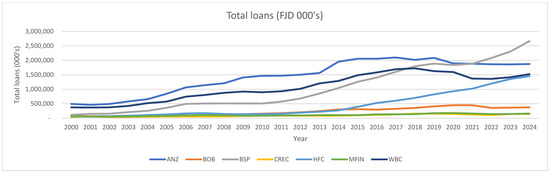

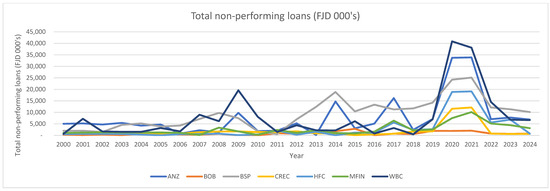

Trends in key bank-specific factors are presented in Figure A1, Figure A2, Figure A3 and Figure A4 (see Appendix A). Figure A1 illustrates the values of net profit after tax. Notably, CCFL (a non-bank) recorded negative profit values in 2000 and 2001, while WBC (a commercial bank) recorded a negative value in 2020. Figure A2 displays the total asset values, with ANZ and BSP (both commercial banks) having the highest asset values, while MFL (a non-bank) has the lowest. Figure A3 shows the total loans issued by the institutions. BSP provided the highest loan amount, while both CCFL and MFL issued the lowest. Figure A4 depicts the levels of non-performing loans. Both commercial banks and non-banks recorded high levels of non-performing loans in the year 2000, which may be attributed to the impact of COVID-19. Overall, WBC recorded the highest level of non-performing loans.

3.2. Dependent Variable

As stated earlier, this study uses two dependent variables: bank risk-taking and bank profitability.

Regarding bank risk-taking, the literature generally offers two main perspectives. The first is grounded in corporate governance theory, where risk is assessed in terms of bank insolvency. Common indicators in this view include the Z-score (Kayed et al., 2025; X. Li et al., 2020; Martínez-Malvar & Baselga-Pascual, 2020; R. Wang et al., 2021) and the variance of asset returns.

The second perspective, aligned with the Basel Accord, adopts a regulatory lens. It measures risk-taking using indicators such as the asset-to-capital ratio (Zhao et al., 2022), deposit-to-loan ratio (Zhao et al., 2022), risk-weighted asset ratio (Qiu et al., 2018), and risky asset ratio (Laeven & Levine, 2009).

However, from a corporate governance standpoint, these regulatory measures primarily capture ex-post risk, meaning they reflect risk outcomes rather than proactive risk-taking behavior. Consequently, following Kayed et al. (2025), this study uses the Z-score to measure bank risk-taking. The Z-score is calculated as follows:

Whereby denotes the return on assets of bank i in year t, represents the ratio of equity to total assets, and is the standard deviation of the return on total assets.

Regarding profitability, following existing studies (Chand et al., 2024b; Le & Ngo, 2020; Yüksel et al., 2018), we employ ROA as a proxy for profitability, which is measured as net income divided by total assets (Chand et al., 2024b).

3.3. Independent Variables

Existing studies have employed several proxies to account for FinTech-related activities. Following existing studies (Alghadi, 2024; Kayed et al., 2025), we measured the development of bank FinTech using dummy variables if the bank offers mobile money and zero otherwise. The details of how FinTech may influence bank risk-taking and profitability are discussed in the literature review section.

3.4. Control Variables

To minimize the risk of model misspecification, the study incorporates several variables that are widely recognized and commonly used in the relevant literature. These include:

- (a)

- Bank size: Larger banks often benefit from diversification across regions and asset types, stronger risk management systems, and better access to capital, which can reduce their overall risk (Adusei, 2015). They may also be perceived as “too big to fail”, which can provide stability through implicit government support (Kaufman, 2014). However, this size also brings complexity, making them harder to monitor and more exposed to systemic risk (Varotto & Zhao, 2018). Empirical studies such as Kayed et al. (2025) and Martínez-Malvar and Baselga-Pascual (2020) found that there are positive effects of bank size on bank risk. In contrast, Sari and Hanafi (2025) found a negative relationship between bank size and bank risk. Hence, the impact of bank size on bank risk-taking is ambiguous.Regarding the relationship between bank size and bank profitability, larger banks often benefit from economies of scale, greater market power, and diversification, leading to higher profitability through lower costs and more revenue opportunities (Baltensperger, 1972). Studies such as Kayed et al. (2025) and Chand et al. (2024b) found a positive effect of bank size on bank profitability. Therefore, we hypothesize that size has a positive effect on bank profitability.

- (b)

- Leverage ratio: On one hand, greater financial leverage increases a bank’s vulnerability to shocks, reduces its equity buffer, and heightens the risk of insolvency and liquidity crises, especially during periods of stress (Kalemli-Ozcan et al., 2012). This view, grounded in theories like the trade-off theory, agency theory, and moral hazard, suggests that excessive reliance on liabilities may incentivize risk-taking behavior, particularly if banks expect deposit insurance or government bailouts (Istiak & Serletis, 2020). On the other hand, proponents of efficient capital structures argue that some level of higher leverage can enhance returns and support growth, provided that risks are well-managed and the bank maintains high-quality assets (DeAngelo & Stulz, 2013). Hence, the impact of leverage on bank risk-taking is ambiguous.On the profitability aspect, high financial leverage may signal increased borrowing or deposit inflows, which can be profit-enhancing if the funds are used to finance high-return loans or investments (Beltratti & Paladino, 2015). Conversely, if the cost of the liabilities, such as interest paid on deposits or borrowings, exceeds the return on assets, it can erode profit margins and lead to losses. Consequently, the effect of bank leverage on bank profitability is ambiguous.

- (c)

- Gearing ratio: A higher gearing ratio implies more reliance on debt, leading to increased fixed obligations, reduced loss of absorption capacity, and heightened sensitivity to interest rate fluctuations, thus elevating the risk of financial distress (Bevan & Danbolt, 2002). Conversely, a lower gearing ratio suggests a stronger equity base, providing a greater buffer against losses and enhanced financial flexibility (Denis & McKeon, 2012). Hence, we postulate a positive association between bank risk-taking and gearing ratio.In terms of profitability, a higher gearing ratio can amplify returns on equity during profitable times, as borrowed funds can generate income exceeding borrowing costs (Mahmud et al., 2016). However, it also inflates interest expenses, directly decreasing profits and increasing vulnerability to economic downturns and interest rate hikes. Empirical studies such as Tulung et al. (2024) reported a positive impact of gearing ratio on bank profitability. Hence, we hypothesize that the gearing ratio is positively associated with bank profitability.

- (d)

- Liquidity ratio: A high liquidity ratio implies a larger portion of deposits is tied up in less liquid loans, increasing the probability of failing to meet sudden depositor withdrawals and potentially leading to asset fire sales or costly emergency borrowing (Acharya & Naqvi, 2012). On the other hand, a low ratio suggests greater readily available funds relative to loans, indicating lower liquidity risk. Hence, we hypothesize that the liquidity ratio is positively associated with bank risk-taking.On the profitability side, higher liquidity implies more deposits are deployed into interest-generating loans, the primary income source for banks (Kashyap et al., 2002). Conversely, a lower ratio reduces lending income, potentially lowering profits, but enhances liquidity. The empirical evidence regarding the impact of liquidity ratio on bank profitability is ambiguous. Studies such as Adelopo et al. (2018) and Hamdi and Hakimi (2019) found a negative relationship, while Rahman et al. (2015) reported positive effects of liquidity ratio on bank performance. Subsequently, the impact of the liquidity ratio has an ambiguous effect on bank performance.

- (e)

- Concentration ratio: Under the conventional “competition-fragility” hypothesis, increased bank competition reduces market power, diminishes franchise value, and thereby incentivizes banks to engage in greater risk-taking behavior (Kabir & Worthington, 2017). In contrast, under the conventional “competition-stability” perspective, greater market power in the loan market may elevate bank risk (Kabir & Worthington, 2017). Higher interest rates charged to borrowers under less competitive conditions can lead to repayment difficulties, thereby intensifying problems of moral hazard and adverse selection (Boyd & De Nicoló, 2005). Hence, the impact of the concentration ratio on bank risk-taking is ambiguous.With regard to bank profitability, high concentration, where a few large banks dominate, can enhance profitability through increased market power, allowing for wider interest rate spreads and potentially lower operating costs due to reduced competitive pressure (Heggestad, 1977). Studies such as Islam and Nishiyama (2016) and Abel et al. (2023) reported a positive association between bank concentration and bank profitability. Hence, we hypothesize that the bank concentration ratio is positively associated with bank profitability.

3.5. Empirical Model

Following the standard literature, the following two models are applied to examine the impact of FinTech on bank risk and profitability:

In the equation, and denote cross-section, time, and error, respectively. Additionally, RISK represents bank risk-taking, as measured by Z-score, and ROA denotes bank profitability. FINTECH represents bank FinTech, while BSIZE, LEV, GEA, LIQ, and HHI denote bank size, leverage ratio, gearing ratio, and concentration ratio, respectively. Panel data may exhibit group effects, time effects, or both, and these can be addressed. Furthermore, the fixed effects model assumes differences in intercepts across groups or time periods (Almaqtari et al., 2019; Mehzabin et al., 2023). The model’s suitability for estimation can be assessed by conducting the Hausman test (Ali & Puah, 2019), where the rejection of the null hypothesis in the Hausman test would indicate support for the use of the fixed effects model.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Descriptive Analysis and Correlation Analysis

The result of the descriptive analysis is presented in Table 2. In terms of the dependent variables, the findings demonstrate that bank risk-taking measured by Z-score ranges from 4.03 to 52.64, but the mean value is 14.11. For profitability, the findings reveal that the mean value for ROA is 0.03, with a minimum of −0.03 and a maximum of 0.12. Regarding the independent variable, the evidence shows that the development of bank FinTech ranges from 0.00 to 1, with a mean of 0.27. Concerning the control variables, bank size and bank leverage have a mean value of 12.96 and 0.86, and the range starts from 10.64 and 0.01 and ends at 15.02 and 0.96, respectively. Regarding gearing and liquidity, the mean values are 8.44 and 1.06 and range from 0.01 and 0.02 to 27.21 and 12.72, respectively. Finally, the concentration ratio has a mean value of 2485.01 and ranges from 1879.50 to 2928.96.

Table 2.

Descriptive analysis.

Table 3 reports the results of the correlation matrix, and the values range from −0.65 to 0.66. The results indicate there are no serious issues of multicollinearity amongst the dependent and independent variables. Table 4 shows the appropriateness of using the fixed-effect model based on the Hausman test.

Table 3.

Correlation matrix.

Table 4.

Hausman test.

4.2. Regression Analysis and Discussion

Table 5 shows how bank FinTech affects bank risk-taking, along with five control factors: bank size, leverage, gearing, liquidity, and concentration ratio. Table 6 presents the results on how bank FinTech impacts bank profitability, using the same five control variables. Model 1 examines the link between bank FinTech development and bank risk, while Model 2 examines the relationship between bank FinTech and profitability.

Table 5.

Fixed effect: the dependent variable is RISK (Model 1).

Table 6.

Fixed effect: the dependent variable is ROA (Model 2).

Model 1 indicates a statistically significant negative relationship between FinTech adoption and banks’ risk-taking behavior, thereby providing empirical support for H1. This suggests that the incorporation of FinTech solutions by banks in Fiji is associated with a more conservative approach to risk, implying a reduced inclination toward high-risk financial activities. These results lend credence to the competition-stability hypothesis (Boyd & De Nicoló, 2005), which posits that increased competition driven by FinTech disruption can foster financial stability by incentivizing institutions to adopt more disciplined risk management strategies.

The findings also align with recent empirical evidence (Banna et al., 2022; Kayed et al., 2025; J. Wang et al., 2023) that points to FinTech’s stabilizing influence on the banking sector. From an economic standpoint, this observed decline in risk-taking may be explained by FinTech’s role in enhancing banks’ internal control systems and operational resilience. Specifically, the deployment of sophisticated technologies such as real-time data analytics, automated credit assessment tools, and machine-learning-based risk detection systems strengthens the ability of banks to monitor, assess, and respond to emerging risks promptly and effectively. Furthermore, FinTech adoption may contribute to a shift in organizational culture, encouraging data-driven decision-making and reinforcing compliance standards. In the context of Fiji’s banking system, where financial institutions are increasingly exposed to both global competition and regulatory scrutiny, these advancements serve to fortify institutional risk buffers. Collectively, the results underscore the dual role of FinTech as both a technological and strategic asset that promotes not only innovation but also systemic stability within the financial sector.

Model 1 reveals a statistically significant negative relationship between FinTech adoption and banks’ risk-taking behavior, thus supporting H1. Specifically, the integration of FinTech solutions within banking institutions in Fiji is associated with a reduced tendency to engage in risky activities. This finding is consistent with the competition-stability hypothesis, which suggests that increased competition, spurred in this case by FinTech innovations, encourages banks to adopt more prudent risk management practices (Boyd & De Nicoló, 2005). The result also aligns with prior studies (Banna et al., 2022; Kayed et al., 2025; J. Wang et al., 2023) that have documented similar effects of FinTech on enhancing banking stability. Economically, the reduction in risk-taking can be attributed to FinTech’s contribution to improving banks’ risk management frameworks and operational efficiency. By leveraging advanced data analytics, automation, and real-time risk monitoring tools, FinTech enables banks to more effectively identify, assess, and mitigate risks, thus promoting a more resilient and stable financial environment.

The findings from Model 2 reveal a positive and statistically significant association between bank-level FinTech development and profitability, thereby supporting H2. This indicates that banks in Fiji that actively invest in and implement FinTech innovations tend to experience enhanced financial performance, particularly through improved return on assets. These results are consistent with the existing literature (Kayed et al., 2025; Lv et al., 2022; Singh et al., 2021), which highlights the value of financial technology in strengthening banking outcomes. Importantly, this relationship reinforces the theoretical premise that technological innovation, along with its potential spillover effects, is a critical enabler of growth and profitability in the banking sector (Kayed et al., 2025). The alignment with disruptive innovation theory is also evident, as FinTech appears not only to modernize legacy banking functions but also to introduce new operational paradigms that challenge traditional models (Solanki & Sujee, 2022). Supporting this view, R. Wang et al. (2021) emphasize that the strategic integration of FinTech enhances managerial efficiency and improves resource mobilization, both of which are instrumental in driving profitability. Moreover, the findings underscore that the benefits of FinTech extend beyond cost reduction or automation. They reflect deeper structural advantages, such as increased agility, customer reach, and competitive positioning. Chhaidar et al. (2023) further argue that technology-led transformations enable banks to optimize service delivery while simultaneously expanding market influence. The Fijian banking context thus provides a compelling case study that affirms the transformative potential of FinTech, offering new empirical insights into its role as a driver of performance in emerging markets.

Furthermore, the results concerning the impact of control variables on dependent variables are as follows: First, regarding risk (as shown in Model 1), bank size demonstrates a positive and statistically significant relationship with bank risk, while leverage and gearing show negative and statistically significant relationships. Liquidity and concentration ratios, however, exhibit an insignificant association with bank risk. Second, concerning profitability (as shown in Model 2), bank size and the concentration ratio exhibit positive and statistically significant relationships with bank profitability. In contrast, leverage, gearing, and the liquidity ratio show statistically insignificant relationships with bank profitability.

4.3. Robustness Check

For robust analysis, we employed pooled OLS, random effects, and GMM estimators. While fixed and random effects models are standard in panel data analysis, they have limitations in capturing the persistence of bank performance over time, as past profitability can significantly influence future outcomes (Athanasoglou et al., 2008). This dynamic relationship introduces endogeneity, particularly when lagged dependent variables are used as regressors—posing challenges in panels with a short time dimension and a large cross-section.

To address this issue, Arellano and Bond (1991) proposed the difference GMM estimator, which eliminates fixed effects by first differencing all variables and uses lagged values as instruments for the endogenous regressors. However, this method has been criticized for inefficiency due to weak instruments, especially in short panels (Arellano & Bover, 1995; Blundell & Bond, 1998). In response, the system GMM estimator was developed, which combines equations in both levels and first differences. This approach enhances efficiency by using lagged differences as instruments for the level equations, assuming they are uncorrelated with individual fixed effects. System GMM thus addresses endogeneity more effectively, yielding more reliable estimates when dealing with persistent dependent variables.

The results of the pooled OLS and random effects models are presented in Table 7 and Table 8, respectively. Notably, the direction and statistical significance of the coefficients are largely consistent with those obtained using the fixed effects model. Table 9 presents the results of the system GMM estimation. The Arellano and Bond test for second-order autocorrelation indicates no significant serial correlation in the residuals for both RISK and ROA. Additionally, the Sargan test results (RISK = 0.12; ROA = 0.39) suggest the instruments used are valid, supporting the appropriateness of the dynamic panel approach.

Table 7.

Robustness results of pooled OLS estimation.

Table 8.

Robustness results of random effect estimation.

Table 9.

Robustness results of GMM estimation.

Regarding the core explanatory variable, FINTECH exhibits a negative relationship with bank risk (Model 1) and a positive relationship with profitability (Model 2). This indicates that increased adoption of FinTech by banks in Fiji reduces risk-taking behavior while enhancing profitability.

Overall, these consistent findings across various models support the conclusion that FinTech adoption has a measurable and beneficial impact on both the risk profile and profitability of banks operating in Fiji.

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

This study investigates the influence of FinTech on bank risk-taking and profitability, focusing on five commercial banks and two credit institutions in Fiji over the period 2000–2024 using the fixed effects model and conducting robustness checks using random effects, pooled OLS, and the GMM method. The empirical findings reveal a negative and statistically significant relationship between FinTech adoption and bank risk-taking and a positive and significant relationship between FinTech and bank profitability. These findings indicate that FinTech development plays a critical role in improving the financial soundness and performance of banks. By facilitating more efficient operations, expanding access to digital financial services, and introducing advanced risk assessment tools, FinTech acts as a catalyst for strengthening the banking sector’s overall resilience and competitiveness.

The implications of these findings are far-reaching for policymakers, financial regulators, and banking institutions. First, the Reserve Bank of Fiji should consider developing targeted incentives and capacity-building programs to encourage the integration of FinTech solutions such as artificial intelligence in credit scoring, blockchain technology for secure and transparent transactions, and digital lending platforms. These tools have the potential to significantly reduce operational costs, minimize default risk, and enhance customer service, which collectively contributes to improved profitability and risk mitigation across the banking sector.

Second, a clear, adaptive, and forward-looking regulatory framework is essential to manage the evolving relationship between traditional financial institutions and FinTech firms. Policymakers should prioritize the development of a regulatory environment that promotes innovation while safeguarding financial stability. This includes creating mechanisms for managing compliance risks, ensuring robust data privacy protection, and facilitating regulatory sandboxes for testing new technologies in a controlled setting. Such measures can enhance banks’ confidence in adopting innovative solutions without fear of regulatory ambiguity or punitive enforcement.

Third, promoting digital financial literacy is crucial for ensuring that the benefits of FinTech are inclusive and sustainable. The government, in collaboration with financial institutions and NGOs, should launch nationwide initiatives aimed at educating individuals and small businesses, especially in rural and underserved communities, on how to use FinTech services securely and effectively. Improved digital literacy can enhance consumer trust, increase adoption rates, and allow banks to expand their digital offerings while reaching broader segments of the population.

While this study makes a significant contribution to the emerging literature on FinTech in small island economies, it is not without limitations. The relatively small number of banks in Fiji, coupled with the limited availability of FinTech-specific data, constrained the sample size and may affect the statistical robustness and generalizability of the findings. Furthermore, measuring the true extent of FinTech adoption remains complex, as available proxies may not fully capture the scope and depth of digital transformation across institutions. Additionally, macroeconomic, regulatory, and institutional variables that may influence bank performance were not fully incorporated into the model. The uniqueness of Fiji’s economic and regulatory environment also limits the applicability of these findings to larger or more technologically advanced economies.

Future research should consider expanding the geographic scope to include other Pacific Island countries or small developing states to enable comparative studies. Disaggregating FinTech into specific service categories, such as digital payments, could yield more granular insights. Moreover, integrating qualitative approaches, such as interviews with bank executives, regulators, and FinTech developers, would provide a richer understanding of the strategic and institutional dynamics shaping FinTech adoption. Finally, future studies could also explore the application of explainable and safe machine learning models to better capture non-linear relationships and enhance predictive accuracy, as suggested in the recent literature (Giudici, 2024). This approach not only enhances model transparency and trustworthiness but also facilitates more informed and reliable decision-making in practice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.A.C., B.S. and K.N.; methodology, S.A.C.; software, S.A.C.; validation, S.A.C. and B.S.; formal analysis, S.A.C., K.N. and A.C.; investigation, S.A.C.; resources, S.A.C., B.S., K.N. and A.C.; data curation, S.A.C., B.S., K.N. and A.C.; writing—original draft preparation, S.A.C., K.N. and A.C.; writing—review and editing, S.A.C.; visualization, S.A.C., K.N. and A.C.; supervision, S.A.C.; project administration, S.A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data used are publicly available. Links to access the data are provided in the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Net profits after tax (FJD 000’s).

Figure A2.

Total assets (FJD 000’s).

Figure A3.

Total loans (FJD 000’s).

Figure A4.

Total non-performing loans (FJD 000’s).

Notes

| 1 | BSP was initially operated as Colonial bank. |

| 2 | HFC was initially operated as credit institutions. |

| 3 | Charter value can be understood as the present value of a bank’s expected future profits (Demsetz et al., 1996). |

References

- Abel, S., Mukarati, J., Jeke, L., & Le Roux, P. (2023). Credit risk and bank profitability in Zimbabwe: An ARDL approach. International Journal of Economics and Finance Studies, 15(1), 370–385. [Google Scholar]

- Acharya, V., & Naqvi, H. (2012). The seeds of a crisis: A theory of bank liquidity and risk taking over the business cycle. Journal of Financial Economics, 106(2), 349–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adalessossi, K. (2023). Impact of E-Banking on the Islamic bank profitability in Sub-Saharan Africa: What are the financial determinants? Finance Research Letters, 57, 104188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelopo, I., Lloydking, R., & Tauringana, V. (2018). Determinants of bank profitability before, during, and after the financial crisis. International Journal of Managerial Finance, 14(4), 378–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adusei, M. (2015). The impact of bank size and funding risk on bank stability. Cogent Economics & Finance, 3(1), 1111489. [Google Scholar]

- Alghadi, M. Y. (2024). The influence of some FinTech service on the performance of Islamic bank in Jordan. International Journal of Data & Network Science, 8(1), 395–400. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, M., & Puah, C. H. (2019). The internal determinants of bank profitability and stability: An insight from banking sector of Pakistan. Management Research Review, 42(1), 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaqtari, F. A., Al-Homaidi, E. A., Tabash, M. I., & Farhan, N. H. (2019). The determinants of profitability of Indian commercial banks: A panel data approach. International Journal of Finance & Economics, 24(1), 168–185. [Google Scholar]

- Aloulou, M., Grati, R., Al-Qudah, A. A., & Al-Okaily, M. (2024). Does FinTech adoption increase the diffusion rate of digital financial inclusion? A study of the banking industry sector. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting, 22(2), 289–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anestiawati, C. A., Amanda, C., Khantinyano, H., & Agatha, A. (2025). Bank FinTech and credit risk: Comparison of selected emerging and developed countries. Studies in Economics and Finance. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, M., & Bond, S. (1991). Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. The Review of Economic Studies, 58(2), 277–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, M., & Bover, O. (1995). Another look at the instrumental variable estimation of error-components models. Journal of Econometrics, 68(1), 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanasoglou, P. P., Brissimis, S. N., & Delis, M. D. (2008). Bank-specific, industry-specific and macroeconomic determinants of bank profitability. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 18(2), 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, M. B. B., Garcia-Nunes, B., Lian, W., Liu, Y., Marulanda, C. P., Sumlinski, M. A., Siddiq, A., Yang, Y., & Vasilyev, D. (2023). The rise and impact of FinTech in Latin America. International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Baltensperger, E. (1972). Economies of scale, firm size, and concentration in banking. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 4(3), 467–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banna, H., Mia, M. A., Nourani, M., & Yarovaya, L. (2022). FinTech-based financial inclusion and risk-taking of microfinance institutions (MFIs): Evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa. Finance Research Letters, 45, 102149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, T., De Jonghe, O., & Schepens, G. (2013). Bank competition and stability: Cross-country heterogeneity. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 22(2), 218–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltratti, A., & Paladino, G. (2015). Bank leverage and profitability: Evidence from a sample of international banks. Review of Financial Economics, 27, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevan, A. A., & Danbolt, J. (2002). Capital structure and its determinants in the UK-a decompositional analysis. Applied Financial Economics, 12(3), 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundell, R., & Bond, S. (1998). Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics, 87(1), 115–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouheni, F. B., Tewari, M., Sidaoui, M., & Hasnaoui, A. (2023). An econometric understanding of FinTech and operating performance. Review of Accounting and Finance, 22(3), 329–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, J. H., & De Nicoló, G. (2005). The theory of bank risk taking and competition revisited. The Journal of Finance, 60(3), 1329–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briguglio, L. (1995). Small island developing states and their economic vulnerabilities. World Development, 23(9), 1615–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broby, D. (2021). Financial technology and the future of banking. Financial Innovation, 7(1), 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L., Yang, Q., & Yu, P. S. (2021). Data science and AI in FinTech: An overview. International Journal of Data Science and Analytics, 12(2), 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chand, S. A., Kumar, R. R., & Stauvermann, P. J. (2021). Determinants of bank stability in a small island economy: A study of Fiji. Accounting Research Journal, 34(1), 22–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chand, S. A., Kumar, R. R., & Stauvermann, P. J. (2023). Determinants of non-performing loans in a small island economy of Fiji: Accounting for COVID-19, bank-type, and globalisation. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 16(10), 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chand, S. A., Kumar, R. R., & Stauvermann, P. J. (2024a). Determinants of bank deposit in a small economy’s banking sector: A study of Fiji. Accounting Research Journal, 37(6), 574–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chand, S. A., Kumar, R. R., Stauvermann, P. J., & Shahbaz, M. (2024b). Determinants of bank profitability—Do institutions, globalization, and global uncertainty matter for banks in Island economies? The case of Fiji. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(6), 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.-H. (2020). Do you know your customer? Bank risk assessment based on machine learning. Applied Soft Computing, 86, 105779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S., & Guo, Q. (2023). FinTech, strategic incentives and investment to human capital, and MSEs innovation. The North American Journal of Economics and Finance, 68, 101963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M., & Qu, Y. (2020). Does bank FinTech reduce credit risk? Evidence from China. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 63, 101398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhaidar, A., Abdelhedi, M., & Abdelkafi, I. (2023). The effect of financial technology investment level on European banks’ profitability. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 14(3), 2959–2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cumming, D., Johan, S., & Reardon, R. (2023). Global FinTech trends and their impact on international business: A review. Multinational Business Review, 31(3), 413–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeAngelo, H., & Stulz, R. M. (2013). Why high leverage is optimal for banks. No. w19139. National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Dell’Ariccia, G., & Marquez, R. (2006). Lending booms and lending standards. The Journal of Finance, 61(5), 2511–2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demsetz, R. S., Saidenberg, M. R., & Strahan, P. E. (1996). Banks with something to lose: The disciplinary role of franchise value. Economic Policy Review, 2(2), 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Nicolo, M. G., Boyd, J. H., & Jalal, A. M. (2006). Bank risk-taking and competition revisited: New theory and new evidence. International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Denis, D. J., & McKeon, S. B. (2012). Debt financing and financial flexibility evidence from proactive leverage increases. The Review of Financial Studies, 25(6), 1897–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominic, J., Joseph, A., & Sisodia, G. (2023). The role of the banking sector in economic resurgence and resilience: Evidence from pacific island countries. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 24(Suppl 1), 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elekdag, S., Emrullahu, D., & Naceur, S. B. (2025). Does FinTech increase bank risk-taking? Journal of Financial Stability, 76, 101360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsaid, H. M. (2023). A review of literature directions regarding the impact of FinTech firms on the banking industry. Qualitative Research in Financial Markets, 15(5), 693–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y., Wang, Q., Wang, F., & Zhao, Y. (2023). Bank fintech, liquidity creation, and risk-taking: Evidence from China. Economic Modelling, 127, 106445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatouh, M., Giansante, S., & Ongena, S. (2024). Leverage ratio, risk-based capital requirements, and risk-taking in the United Kingdom. Financial Markets, Institutions & Instruments, 33(1), 31–60. [Google Scholar]

- Giudici, P. (2024). Safe machine learning. Statistics, 58(3), 473–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomber, P., Kauffman, R. J., Parker, C., & Weber, B. W. (2018). On the FinTech revolution: Interpreting the forces of innovation, disruption, and transformation in financial services. Journal of Management Information Systems, 35(1), 220–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gounder, N., & Sharma, P. (2012). Determinants of bank net interest margins in Fiji, a small island developing state. Applied Financial Economics, 22(19), 1647–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafeez, B., Li, X., Kabir, M. H., & Tripe, D. (2022). Measuring bank risk: Forward-looking z-score. International Review of Financial Analysis, 80, 102039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdi, H., & Hakimi, A. (2019). Does liquidity matter on bank profitability? Evidence from a nonlinear framework for a large sample. Business and Economics Research Journal, 10(1), 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Heggestad, A. A. (1977). Market structure, risk and profitability in commercial banking. The Journal of Finance, 32(4), 1207–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibidunni, A. S., Ufua, D. E., & Opute, A. P. (2022). Linking disruptive innovation to sustainable entrepreneurship within the context of small and medium firms: A focus on Nigeria. African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation and Development, 14(6), 1591–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M. S., & Nishiyama, S.-I. (2016). The determinants of bank profitability: Dynamic panel evidence from South Asian countries. Journal of Applied Finance and Banking, 6(3), 77. [Google Scholar]

- Istiak, K., & Serletis, A. (2020). Risk, uncertainty, and leverage. Economic Modelling, 91, 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaraman, T., Singh, B., & Sharma, A. (2017). Determinants of efficiency of Fiji’s commercial banks: An empirical study: 2002–16. Fijian Studies: A Journal of Contemporary Fiji, 15(2), 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, X. (2024). FinTech penetration, charter value, and bank risk-taking. Journal of Banking & Finance, 161, 107111. [Google Scholar]

- Jović, Ž., & Nikolić, I. (2022). The darker side of FinTech: The emergence of new risks. Zagreb International Review of Economics & Business, 25(SCI), 46–63. [Google Scholar]

- Kabir, M. N., & Worthington, A. C. (2017). The ‘competition–stability/fragility’nexus: A comparative analysis of Islamic and conventional banks. International Review of Financial Analysis, 50, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalemli-Ozcan, S., Sorensen, B., & Yesiltas, S. (2012). Leverage across firms, banks, and countries. Journal of International Economics, 88(2), 284–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashyap, A. K., Rajan, R., & Stein, J. C. (2002). Banks as liquidity providers: An explanation for the coexistence of lending and deposit-taking. The Journal of Finance, 57(1), 33–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, G. G. (2014). Too big to fail in banking: What does it mean? Journal of Financial Stability, 13, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayed, S., Alta’any, M., Meqbel, R., Khatatbeh, I. N., & Mahafzah, A. (2025). Bank FinTech and bank performance: Evidence from an emerging market. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting, 23(2), 518–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeley, M. C. (1990). Deposit insurance, risk, and market power in banking. The American Economic Review, 80, 1183–1200. [Google Scholar]

- Kharrat, H., Trichilli, Y., & Abbes, B. (2024). Relationship between FinTech index and bank’s performance: A comparative study between Islamic and conventional banks in the MENA region. Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research, 15(1), 172–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjellman, A., Björkroth, T., Kangas, T., Tainio, R., & Westerholm, T. (2019). Disruptive innovations and the challenges for banking. International Journal of Financial Innovation in Banking, 2(3), 232–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukman, T., & Gričar, S. (2025). Blockchain for quality: Advancing security, efficiency, and transparency in financial systems. FinTech, 4(1), 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J., & Rani, V. (2024). Investigating the dynamics of FinTech adoption: An empirical study from the perspective of mobile banking. Journal of Economic and Administrative Sciences. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R. R., Stauvermann, P. J., Patel, A., & Prasad, S. S. (2018). Determinants of non-performing loans in banking sector in small developing island states: A study of Fiji. Accounting Research Journal, 31(2), 192–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laeven, L., & Levine, R. (2009). Bank governance, regulation and risk taking. Journal of Financial Economics, 93(2), 259–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T. D., & Ngo, T. (2020). The determinants of bank profitability: A cross-country analysis. Central Bank Review, 20(2), 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-C., Li, X., Yu, C.-H., & Zhao, J. (2021). Does FinTech innovation improve bank efficiency? Evidence from China’s banking industry. International Review of Economics & Finance, 74, 468–483. [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann, M. (2020). Global rules for a global market place?-Regulation and supervision of FinTech providers. BU Int’l LJ, 38, 118. [Google Scholar]

- Leo, M., Sharma, S., & Maddulety, K. (2019). Machine learning in banking risk management: A literature review. Risks, 7(1), 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, K., & Sung, A. (2018). FinTech (Financial Technology): What is it and how to use technologies to create business value in FinTech way? International Journal of Innovation, Management and Technology, 9(2), 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. (2025). Impact of FinTech on bank risks: The role of bank digital transformation. Applied Economics Letters, 32(6), 895–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C., He, S., Tian, Y., Sun, S., & Ning, L. (2022). Does the bank’s FinTech innovation reduce its risk-taking? Evidence from China’s banking industry. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 7(3), 100219. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X., Tripe, D., Malone, C., & Smith, D. (2020). Measuring systemic risk contribution: The leave-one-out z-score method. Finance Research Letters, 36, 101316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., & Zhu, J. (2024). The impact of foreign participation on risk-taking in Chinese commercial banks: The co-governance role of equity checks and foreign supervision. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 85, 102387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.-P., & Kosim, Z. (2022). An empirical study to explore the influence of the COVID-19 crisis on consumers’ behaviour towards cashless payment in Malaysia. Journal of Financial Services Marketing, 29, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusy, L., Hermanto, Y. B., Panjaitan, T. W., & Widyastuti, M. (2018). Effects of current ratio and debt-to-equity ratio on return on asset and return on equity. International Journal of Business and Management Invention (IJBMI), 7(12), 31–39. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, S., Du, Y., & Liu, Y. (2022). How do FinTechs impact banks’ profitability?—An empirical study based on banks in China. FinTech, 1(2), 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Y., Ji, Z., Zhang, X., & Zhan, Z. (2023). Can FinTech alleviate the financing constraints of enterprises?—Evidence from the Chinese securities Market. Sustainability, 15(5), 3876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, K., Mallik, A., Imtiaz, M. F., & Tabassum, N. (2016). The bank-specific factors affecting the profitability of commercial banks in Bangladesh: A panel data analysis. International Journal of Managerial Studies and Research, 4(7), 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus, A. J. (1984). Deregulation and bank financial policy. Journal of Banking & Finance, 8(4), 557–565. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Malvar, M., & Baselga-Pascual, L. (2020). Bank risk determinants in Latin America. Risks, 8(3), 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meckling, W. H., & Jensen, M. C. (1976). Theory of the Firm. Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure, 3(4), 305–360. [Google Scholar]

- Mehzabin, S., Shahriar, A., Hoque, M. N., Wanke, P., & Azad, M. A. K. (2023). The effect of capital structure, operating efficiency and non-interest income on bank profitability: New evidence from Asia. Asian Journal of Economics and Banking, 7(1), 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misati, R., Osoro, J., Odongo, M., & Abdul, F. (2024). Does digital financial innovation enhance financial deepening and growth in Kenya? International Journal of Emerging Markets, 19(3), 679–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mothobi, O., & Kebotsamang, K. (2024). The impact of network coverage on adoption of FinTech and financial inclusion in sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Economic Structures, 13(1), 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugraha, D. P., Setiawan, B., Nathan, R. J., & Fekete-Farkas, M. (2022). FinTech adoption drivers for innovation for SMEs in Indonesia. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 8(4), 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owusu, A., & Gupta, A. (2024). Identifying the risk culture of banks using machine learning. International Journal of Managerial Finance, 20(2), 377–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polireddi, N. S. A. (2024). An effective role of artificial intelligence and machine learning in banking sector. Measurement: Sensors, 33, 101135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H., Huang, Y. P., & Ji, Y. (2018). How does FinTech development affect traditional banking in China? The perspective of online wealth management products. Journal of Financial Research (Chinese Version), 461(11), 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M. M., Hamid, M. K., & Khan, M. A. M. (2015). Determinants of bank profitability: Empirical evidence from Bangladesh. International Journal of Business and Management, 10(8), 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, R. (2004). The implications of increasing globalization and regionalism for the economic growth of small island states. World Development, 32(2), 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, M. (2025). Technology and communal culture of sharing and giving: Implications on household savings behavior in Fiji. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 43(1), 166–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reserve Bank of Fiji. (2016). 2016 Annual report of the Fiji financial intelligence unit. Available online: https://www.rbf.gov.fj/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/FIU-AR-2016.pdf (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Reserve Bank of Fiji. (2018). 2017–2018 Annual report of the Reserve Bank of Fiji. Available online: https://www.rbf.gov.fj/rbf-annual-report-august-2017-july-2018/ (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Reserve Bank of Fiji. (2022). Fiji national financial inclusion 2022–2030 strategy. Available online: https://www.rbf.gov.fj/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/NFIS-2022-2030.pdf (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Reserve Bank of Fiji. (2024). Published disclosure statements, RBF, Suva, Fiji. Available online: www.rbf.gov.fj/Left-Menu/Regulatory-Framework/Published-Disclosure-Statements.aspx (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Sari, D. R., & Hanafi, M. M. (2025). Funding liquidity risk and banks’ risk-taking behavior: The role of the COVID-19 crisis and bank size. Studies in Economics and Finance. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaeck, K., & Čihák, M. (2008). How does competition affect efficiency and soundness in banking? New empirical evidence (No. 932). ECB Working Paper. [Google Scholar]

- Siek, M., & Sutanto, A. (2019, August). Impact analysis of FinTech on banking industry. In 2019 international conference on information management and technology (ICIMTech) (Vol. 1, pp. 356–361). IEEE. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, R., Malik, G., & Jain, V. (2021). FinTech effect: Measuring impact of FinTech adoption on banks’ profitability. International Journal of Management Practice, 14(4), 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S. S. (2020). Emerging technologies and implications for financial cybersecurity. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 10(1), 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solanki, R., & Sujee, L. S. (2022). FinTech: A disruptive innovation of the 21st century, or is it? Global Business and Management Research, 14(2s), 76–87. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, B., Singh, S., & Jain, S. (2023). Bank competition, risk-taking and financial stability: Insights from an emerging economy. Competitiveness Review: An International Business Journal, 33(5), 959–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, G. H., & Feldman, R. J. (2004). Too big to fail: The hazards of bank bailouts. Rowman & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Stiroh, K. J. (2004). Diversification in banking: Is noninterest income the answer? Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 36, 853–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stulz, R. M. (2019). FinTech, bigtech, and the future of banks. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 31(4), 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M., Hou, Y. G., Goodell, J. W., & Hu, Y. (2024). FinTech and corporate risk-taking: Evidence from China. Finance Research Letters, 64, 105411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarawneh, A., Abdul-Rahman, A., Mohd Amin, S. I., & Ghazali, M. F. (2024). A systematic review of FinTech and banking profitability. International Journal of Financial Studies, 12(1), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulung, J. E., Sondakh, J. J., Wangke, S. J. C., & Posumah, R. F. K. (2024). Effects of capital ratio, quality of receivables, liquidity, and gearing ratio on profitability: A Study Financial Institutions’ governance. Journal of Governance and Regulation, 13(3), 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M. H., Mollah, S., & Ali, M. H. (2020). Does cyber tech spending matter for bank stability? International Review of Financial Analysis, 72, 101587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia, O. C., & Bolaños, A. O. (2018). Bank capital buffers around the world: Cyclical patterns and the effect of market power. Journal of Financial Stability, 38, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varotto, S., & Zhao, L. (2018). Systemic risk and bank size. Journal of International Money and Finance, 82, 45–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vives, X. (2017). The impact of FinTech on banking. European Economy, 2, 97–105. [Google Scholar]

- Von Solms, J. (2021). Integrating Regulatory Technology (RegTech) into the digital transformation of a bank Treasury. Journal of Banking Regulation, 22(2), 152–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Huang, X., Gu, Q., Song, Z., & Sun, R. (2023). How does FinTech affect bank risk? A perspective based on financialized transfer of government implicit debt risk. Economic Modelling, 128, 106498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R., Liu, J., & Luo, H. (2021). FinTech development and bank risk taking in China. The European Journal of Finance, 27(4–5), 397–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2024). World Development Indicators. World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, B., & Qi, Y. (2025). Does FinTech improve the risk-taking capacity of commercial banks? Empirical evidence from China. Economics, 19(1), 20250143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L., & Wang, S. (2022). Do FinTech applications promote regional innovation efficiency? Empirical evidence from China. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences, 83, 101258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yüksel, S., Mukhtarov, S., Mammadov, E., & Özsarı, M. (2018). Determinants of profitability in the banking sector: An analysis of post-soviet countries. Economies, 6(3), 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Zhang, W., & Lee, C. C. (2025). Bank leverage and systemic risk: Impact of bank risk-taking and inter-bank business. International Journal of Finance & Economics, 30(2), 1450–1474. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J., Li, X., Yu, C. H., Chen, S., & Lee, C. C. (2022). Riding the FinTech innovation wave: FinTech, patents and bank performance. Journal of International Money and Finance, 122, 102552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).