Decoding ESG: Consumer Perceptions, Ethical Signals and Financial Outcomes

Abstract

1. Introduction

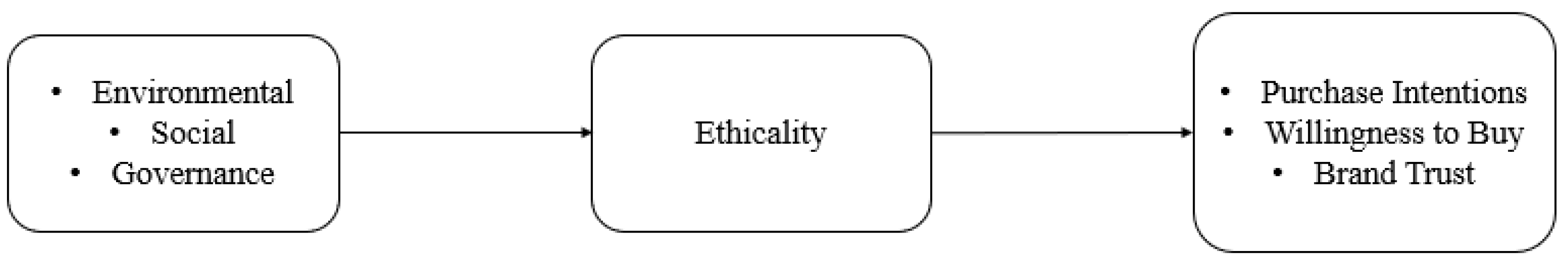

2. Literature Review: ESG

3. Hypothesis Development

4. Methods

4.1. Procedure

4.2. Results and Discussion

5. General Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practitioner Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B. Measures

Appendix B.1. Purchase Intentions (H. S. Bansal et al., 2004)

- Unlikely/Likely

- Definitely no/Definitely yes

- Not inclined to/Inclined to

- Improbable/Probable

- No chance at all/Good chance

Appendix B.2. Willingness to Buy (Adapted from Dodds et al., 1991; MacKenzie et al., 1986)

- I would consider buying coffee from this company.

- I am likely to purchase this coffee in the future.

- I would choose this company’s coffee over other brands.

- I would be willing to try this company’s coffee.

Appendix B.3. Brand Trust (Adapted from Delgado-Ballester, 2004; Chaudhuri & Holbrook, 2001)

- I trust this company to do what’s right.

- I believe this company keeps its promises.

- I consider this company to be dependable.

- This company seems honest.

Appendix B.4. Perceived Ethicality (Adapted from Brunk, 2010; Vitell & Muncy, 2005)

- This company behaves ethically.

- This company is socially responsible.

- This company is concerned with doing the right thing.

- This company makes ethical business decisions.

Appendix B.5. Perceived Authenticity (Adapted from Morhart et al., 2015)

- I believe this company’s message is authentic.

- I believe this company’s message is genuine.

- I believe this company’s message is true.

- I believe that this company’s message is legitimate.

Appendix B.6. Environmental Perceptions (Klein & Dawar, 2004)

- This company operates in a manner that is less harmful to environment than other companies.

- This company operates in a manner that is better for the environment than other companies.

- This company is more environmentally responsible than other companies.

Appendix B.7. Social Perceptions (Adapted from Waites et al., 2024)

- This company treats people fairly.

- This company supports the well-being of its workers and partners.

- This company is committed to social responsibility.

- This company helps build stronger communities.

- This company ensures fair compensation for its workers.

Appendix B.8. Governance Perceptions (Items Created)

- This company is committed to ethical standards.

- This company values transparency in how it operates.

- This company appears to have strong governance practices.

- This company acts with integrity in its decision-making.

References

- Aguilera, R. V., Rupp, D. E., Williams, C. A., & Ganapathi, J. (2006). Putting the S back in corporate social responsibility: A multilevel theory of social change in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 32(3), 836–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, H., Yaqub, M., & Lee, S. H. (2023). Environmental-, social-, and governance-related factors for business investment and sustainability: A scientometric review of global trends. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 26, 2965–2987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, N., Mobarek, A., & Roni, N. N. (2021). Revisiting the impact of ESG on financial performance of FTSE350 UK firms: Static and dynamic panel data analysis. Cogent Business and Management, 8(1), 1900500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, H. S., Irving, P. G., & Taylor, S. F. (2004). A three-component model of customer to service providers. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 32(3), 234–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P., & Roth, K. (2000). Why companies go green: A model of ecological responsiveness. Academy of Management Journal, 43(4), 717–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, M., Wiegand, N., & Reinartz, W. J. (2019). Does it pay to be real? Understanding authenticity in TV advertising. Journal of Marketing, 83(1), 24–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker-Olsen, K. L., Cudmore, B. A., & Hill, R. P. (2006). The impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior. Journal of Business Research, 59(1), 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, C. B., & Sen, S. (2004). Doing better at doing good: When, why, and how consumers respond to corporate social initiatives. California Management Review, 47(1), 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S., Jackson, G., & Matten, D. (2012). Corporate social responsibility and institutional theory: New perspectives on private governance. Socio-Economic Review, 10(1), 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S., Millington, A., & Rayton, B. (2007). The contribution of corporate social responsibility to organizational commitment. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 18(10), 1701–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunk, K. H. (2010). Exploring origins of ethical company/brand perceptions—A consumer perspective of corporate ethics. Journal of Business Research, 63(3), 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buell, R. W., & Kalkanci, B. (2021). How transparency into internal and external responsibility initiatives influences consumer choice. Management Science, 67(2), 932–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, A., & Holbrook, M. B. (2001). The chain of effects from brand trust and brand affect to brand performance: The role of brand loyalty. Journal of Marketing, 65(2), 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, G. L., Feiner, A., & Viehs, M. (2015). From the stockholder to the stakeholder: How sustainability can drive financial outperformance. University of Oxford, Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment. Available online: https://arabesque.com/research/From_the_stockholder_to_the_stakeholder_web.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Clément, A., Robinot, É., & Trespeuch, L. (2022). Improving ESG scores with sustainability concepts. Sustainability, 14(20), 13154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Ballester, E. (2004). Applicability of a brand trust scale across product categories: A multigroup invariance analysis. European Journal of Marketing, 38(5/6), 573–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, W. B., Monroe, K. B., & Grewal, D. (1991). Effects of price, brand, and store information on buyers’ product evaluations. Journal of Marketing Research, 28(3), 307–319. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, Y., Yang, F., & Xiong, L. (2023). Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance and firm value: Evidence from Chinese manufacturing firms. Sustainability, 15(17), 12858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, R. G., Ioannou, I., & Serafeim, G. (2014). The impact of corporate sustainability on organizational processes and performance. Management Science, 60(11), 2835–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, R. G., & Klimenko, S. (2019). The investor revolution. Harvard Business Review, 97(3), 106–116. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles, R. G., & Krzus, M. P. (2018). Why companies should report financial risks from climate change. MIT Sloan Management Review, 59(3), 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Edmans, A. (2011). Does the stock market fully value intangibles? Employee satisfaction and equity prices. Journal of Financial Economics, 101(3), 621–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. (1997). The triple bottom line. Environmental Management: Readings and Cases, 2, 49–66. [Google Scholar]

- Erben Yavuz, A., Kocaman, B. E., Doğan, M., Hazar, A., Babuşcu, Ş., & Sutbayeva, R. (2024). The impact of corporate governance on sustainability disclosures: A comparison from the perspective of financial and non-financial firms. Sustainability, 16(19), 8400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R. J. (1993). Social desirability bias and the validity of indirect questioning. Journal of Consumer Research, 20(2), 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foreh, M. R., & Grier, S. (2003). When is honesty the best policy? The effect of stated company intent on consumer skepticism. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 13(3), 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friede, G., Busch, T., & Bassen, A. (2015). ESG and financial performance: Aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies. Journal of Sustainable Finance and Investment, 5(4), 210–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gherghina, Ș. C. (2024). Corporate finance and environmental, social, and governance (ESG) practices. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(7), 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenster, N., Bauer, R., Derwall, J., & Koedijk, K. (2011). The economic value of corporate eco-efficiency. European Financial Management, 17(4), 679–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J. S., Freeman, R. E., & Abreu, M. C. S. D. (2015). Stakeholder theory as an ethical approach to effective management: Applying the theory to multiple contexts. Revista Brasileiras de Gestão de Negócios, 17(55), 858–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, P., & Apaolaza-Ibáñez, V. (2012). Consumer attitude and purchase intention toward green energy brands: The roles of psychological benefits and environmental concern. Journal of Business Research, 65(9), 1254–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2022). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (3rd ed.). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ioannou, I., & Serafeim, G. (2015). The impact of corporate social responsibility on investment recommendations: Analysts’ perceptions and shifting institutional logics. Strategic Management Journal, 36(7), 1053–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, H., & Harjoto, M. A. (2012). The causal effect of corporate governance on corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 106(1), 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M., Serafeim, G., & Yoon, A. (2016). Corporate sustainability: First evidence on materiality. The Accounting Review, 91(6), 1697–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, J., & Dawar, N. (2004). Corporate social responsibility and consumers’ attributions and brand evaluations in a product–harm crisis. International Journal of research in Marketing, 21(3), 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonelli, S., Muhn, M., Rauter, T., & Sran, G. (2024). How do consumers use ESG disclosure? Evidence from a randomized field experiment with everyday product purchases. University of Chicago. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein, D. R., Drumwright, M. E., & Braig, B. M. (2004). The effect of corporate social responsibility on customer donations to corporate-supported nonprofits. Journal of Marketing, 68(4), 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loken, B., Ahluwalia, R., & Houston, M. J. (2010). Brands and brand management: Contemporary research perspectives. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Loken, B., Barsalou, L. W., & Joiner, C. (2008). Categorization theory and research in consumer psychology. Handbook of Consumer Psychology, 5, 133–165. [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie, S. B., Lutz, R. J., & Belch, G. E. (1986). The role of attitude toward the ad as a mediator of advertising effectiveness: A test of competing explanations. Journal of Marketing Research, 23(2), 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, G. P., Serena, M., & Julkovski, D. J. (2024). Environmental, social and governance (ESG) and consumer behavior: Trends towards conscious consumption. Revista de Gestão Social e Ambiental, 18(10), e08374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinsey and Company & NielsenIQ. (2023, February 8). Consumers care about sustainability—And back it up with their wallets. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/consumer-packaged-goods/our-insights/consumers-care-about-sustainability-and-back-it-up-with-their-wallets (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Merrick, A. (2024). Consumers say they care about ESG, but don’t spend like they do. Chicago Booth Review. Available online: https://www.chicagobooth.edu/review/consumers-say-they-care-about-esg-but-dont-spend-like-they-do (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Mohr, L. A., & Webb, D. J. (2005). The effects of corporate social responsibility and price on consumer responses. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 39(1), 121–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morhart, F., Malär, L., Guèvremont, A., Girardin, F., & Grohmann, B. (2015). Brand authenticity: An integrative framework and measurement scale. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 25(2), 200–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morwitz, V. G. (2014). Consumers’ purchase intentions and their behavior. Foundations and Trends in Marketing, 7(3), 181–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murata, R., & Hamori, S. (2021). ESG disclosures and stock price crash risk. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 14(2), 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parguel, B., Benoît-Moreau, F., & Larceneux, F. (2011). How sustainability ratings might deter ‘greenwashing’: A closer look at ethical corporate communication. Journal of Business Ethics, 102(1), 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, A., & Rodríguez del Bosque, I. (2015). Corporate social responsibility and customer loyalty: Exploring the role of identification, satisfaction and type of company. Journal of Services Marketing, 29(1), 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puriwat, W., & Tripopsakul, S. (2023). Sustainability matters: Unravelling the power of ESG in fostering brand love and loyalty across generations and product involvements. Sustainability, 15(15), 11578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahat, B., & Nguyen, P. (2024). The impact of ESG profile on firm’s valuation in emerging markets. International Review of Financial Analysis, 95, 103361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, M. R., Shahimi, S., & Alma’amun, S. (2024). Does mediation matter in explaining the relationship between ESG and bank financial performance? A scoping review. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(8), 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmeltz, L. (2012). Consumer-oriented CSR communication: Focusing on ability or morality? Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 17(1), 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schons, L., & Steinmeier, M. (2016). Walk the talk? How symbolic and substantive CSR actions affect firm performance depending on stakeholder proximity. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 23(6), 358–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seemann, A., Guyoton, S., Bianchi, A., & Han, J. (2023). Do ESG efforts create value? Available online: https://www.bain.com/insights/do-esg-efforts-create-value/ (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Sen, S., & Bhattacharya, C. B. (2001). Does doing good always lead to doing better? Consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility. Journal of Marketing Research, 38(2), 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seok, J., Kim, Y., & Oh, Y. K. (2024). How ESG shapes firm value: The mediating role of customer satisfaction. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 208, 123714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J. J., Iglesias, O., & Batista-Foguet, J. M. (2012). Does having an ethical brand matter? The influence of consumer perceived ethicality on trust, affect and loyalty. Journal of Business Ethics, 111, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, M. (1973). Job market signaling. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 87(3), 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, T., & Teo, P.-C. (2025). A literature review of understanding consumer behavior in ESG through Stimulus-Response (S-R) theory. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 15(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, R., & Mackenzie, C. (Eds.). (2017). Responsible investment. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Syarkani, Y., Subu, M. A., & Waluyo, I. (2023). Impact of ESG performance on firm value: A comparison of emerging and developed markets. Commercium, 2(4), 204–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripopsakul, S., & Puriwat, W. (2022). Understanding the impact of ESG on brand trust and customer engagement. Journal of Human, Earth, and Future, 3(4), 430–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitell, S. J., & Muncy, J. (2005). The Muncy–Vitell consumer ethics scale: A modification and application. Journal of Business Ethics, 62, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waites, S. F., Farmer, A., & Collier, J. (2024). Good people good planet: Investigating the interconnection between social and environmental sustainability. Journal of Business Research, 184, 114897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K., Habib, R., & Hardisty, D. J. (2019). How to SHIFT consumer behaviors to be more sustainable: A literature review and guiding framework. Journal of Marketing, 83(3), 22–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y., Gürhan-Canli, Z., & Schwarz, N. (2006). The effect of corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities on companies with bad reputations. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 16(4), 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Environmental Perceptions | Social Perceptions | Governance Perceptions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario | M (SD) | t-Values | M (SD) | t-Values | M (SD) | t-Values |

| Environmental | 5.60 (1.07) | 4.89 (0.96) | 4.77 ** | 5.35 (0.97) | 2.03 * | |

| Social | 5.02 (1.21) | 3.51 ** | 5.70 (0.89) | 5.70 (0.95) | 0.05 | |

| Goverance | 4.91 (1.10) | 2.79 ** | 5.17 (1.02) | 3.05 ** | 5.71 (0.98) | |

| Control | 3.95 (1.31) | 7.59 ** | 4.16 (1.12) | 8.42 ** | 4.23 (1.19) | 7.47 ** |

| Purchase Intentions | Willingness to Buy | Brand Trust | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) |

| Environmental | 5.43 (1.34) | 6.48 (1.94) | 5.86 (1.86) |

| Social | 5.40 (1.32) | 6.57 (1.83) | 6.53 (1.92) |

| Governance | 5.40 (1.56) | 6.62 (2.25) | 6.23 (1.94) |

| Control | 4.71 (1.67) | 5.27 (2.11) | 4.80 (2.02) |

| Mediation Analyses: Indirect Effects | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Purchase Intentions | Willingness to Buy | Brand Trust | |||||||

| Ethicality | a*b | LLCI | ULCI | a*b | LLCI | ULCI | a*b | LLCI | ULCI |

| Environmental | 0.65 | 0.34 | 1.01 | 0.89 | 0.53 | 1.30 | 1.04 | 0.66 | 1.48 |

| Social | 0.83 | 0.46 | 1.25 | 1.15 | 0.73 | 1.61 | 1.34 | 0.91 | 1.85 |

| Goverance | 0.59 | 0.30 | 0.94 | 0.81 | 0.47 | 1.22 | 0.95 | 0.57 | 1.41 |

| Authenticity | a*b | LLCI | ULCI | a*b | LLCI | ULCI | a*b | LLCI | ULCI |

| Environmental | 0.17 | −0.03 | 0.38 | 0.26 | −0.04 | 0.60 | 0.28 | −0.05 | 0.61 |

| Social | 0.36 | 0.15 | 0.62 | 0.56 | 0.26 | 0.92 | 0.61 | 0.28 | 0.95 |

| Goverance | 0.13 | −0.10 | 0.38 | 0.20 | −0.15 | 0.58 | 0.21 | −0.17 | 0.61 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Waites, S.F. Decoding ESG: Consumer Perceptions, Ethical Signals and Financial Outcomes. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 361. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18070361

Waites SF. Decoding ESG: Consumer Perceptions, Ethical Signals and Financial Outcomes. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(7):361. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18070361

Chicago/Turabian StyleWaites, Stacie F. 2025. "Decoding ESG: Consumer Perceptions, Ethical Signals and Financial Outcomes" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 7: 361. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18070361

APA StyleWaites, S. F. (2025). Decoding ESG: Consumer Perceptions, Ethical Signals and Financial Outcomes. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(7), 361. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18070361