Abstract

The research concentrates on determining the degree of internationalization of born global SMEs, believing that some push factors determine internationalization, pull factors, and internal firm-specific factors. Three important factors were found in looking into the causes of internationalization in born global firms: push, pull, and internal firm-specific factors. The study used a survey instrument with a sample of 280 manufacturing-related SMEs chosen from manufacturing clusters in India. A metric called the “index of internationalization” is used to gauge how internationalization in SMEs takes shape. The results demonstrated that internal firm-specific factors influence the internationalization of firms relatively highly compared to push and pull factors. The results unequivocally demonstrate that developing economies have distinct factors that cause internationalization, opening up new avenues for further study. The research aids in the identification of the elements that will enhance early internationalization and tries to draw the attention of young entrepreneurs. This research also helps prioritize the factors responsible for early internationalization. These findings are pertinent for the practitioners and researchers working in this area. This research is helpful for start-ups looking for global opportunities; this research categorizes factors significant in the global journey of the born global firms.

1. Introduction

The development and extension of organizations into the international markets are acknowledged to benefit significantly from internationalization; the determinants of internationalization have attracted academic and practitioners’ attention previously; however, with the advancement of technology in communication and transport, the determinants of internationalization tend to restructure (Moed et al., 2005). The concept of rapid globalization emerged, and global firms surfaced recently in the international arena. Therefore, more information is needed about the factors that influence the birth of global SMEs’ internationalization in India, an economy that is expanding quickly (Nwankwo & Gbadamosi, 2020). Globalization refers to the broader economic, political, and cultural integration of markets and societies on a global scale (Halawa, 2018; Riefler, 2012), whereas internationalization pertains to firm-level strategies for expanding operations across borders while adapting to specific market conditions (Bıçakcıoğlu-Peynirci, 2023).

Small and medium-sized businesses (SMEs) are essential to a nation’s growth in this fast-paced age of globalization, according to Bérard and Delerue (2010). An analysis of the company’s globalization is becoming increasingly significant in a constantly changing world. One of, if not the most significant, ways that businesses have responded to the generalized rise in competition and dangers to their existence due to the gradual liberalization of global commerce is via international growth. Large companies have traditionally dominated the international business sector, with smaller companies often remaining domestic (G. Knight & Khan, 2024). As a result, big multinational corporations received more attention in conventional theories of internationalization than small enterprises. Nonetheless, regardless of a company’s size, industry, or place of origin, internationalization has expanded due to business global expansion (Williams & Shaw, 2011). The competitive landscape for small and big enterprises is changing due to globalization, and internationalization concerns will only become more significant for all companies. Understanding the who, what, when, and why of a company’s internationalization has grown in importance as a study area for international entrepreneurship (Kiss et al., 2012).

Analyzing cross-border businesses regardless of size, age, or prior international experience is necessary to determine whom to target and when (Jones & Pitelis, 2015). Smaller businesses moving toward internationalization or newly established businesses are usually called born global firms that are internationalizing (G. A. Knight & Cavusgil, 2004). With the advancement in information technology and communication networks, these businesses also thrive in global markets. These organizations slowly and steadily make their way into the international market and claim a substantial market share globally today. The entrance strategies that these businesses choose throughout the internationalization process also vary significantly in this respect. Cyert and March (1965) previously said that the methods of internationalization result from any company’s development, which assumes a natural evolution in competitive enterprises via exports or direct investments. Hitt et al. (2005) state that when a firm chooses to go global, it must consider an important issue: how to enter the market. Further, Liu (2017) asserted that adopting a collaborative entry strategy with distributors can significantly enhance the rapid expansion of born global firms, while transnational entrepreneurs play a fundamental role in fostering and extending international networks. As a result, several possibilities for internationalization become available, including licensing, exporting, and establishing strategic partnerships via acquisitions or the complete establishment of a subsidiary. Numerous other researchers discovered different entrance mode classifications in the literature, but they are all relatively comparable (Canabal & White, 2008; Zhang et al., 2022).

It becomes necessary to differentiate between determinants of internationalization, i.e., the elements that make internationalization feasible and those that are the drivers of the internationalization process. According to Fernandes et al. (2020), we assume that determinants are the driving forces behind a company’s want or choice to internationalize or the things that may spur a company’s desire or choice to go global. Also, Manohar et al. (2025) argue that born global firms from emerging economies face significant liabilities and risks; however, they exhibit a strong strategic inclination to expand across greater distances during the internationalization process. The need to minimize or diversify risks also includes factors related to favorable growth prospects in global markets, low competition, and permitting advancement in technology, among other things. For simplicity, the determinants were divided into three categories, i.e., push factors (PUFs), pull factors (PLFs), and internal firm-specific characteristics (IFCs) and assumed to have an impact on the internationalization index (II).

These elements helped the corporation expand its activities internationally regarding variables that encourage its internationalization process (Arpa et al., 2012). They are regarded as the elements the business owner acknowledges as the catalysts for the internationalization plan or those that allowed his company to expand internationally (Falahat et al., 2023; Kayacı, 2021). Within this framework, our research aims to examine the correlation between the company’s internationalization index and the determinants of this index. We will base our analysis on the responses acquired by emailing newly established global businesses. Indian SMEs are growing at a tremendous rate, and the global presence of these SMEs significantly increased in the last 5 years. While the conceptualizations are valuable depictions of the environment in which these firms operate, there is still substantial evidence about how push and pull factors affect the internationalization of born globals after accounting for firm-specific characteristics. Born global firms are defined as companies that achieve at least 25% of their total sales from foreign markets within two to three years of their establishment (G. Knight & Khan, 2024). Unlike firms following gradual internationalization models, born globals exhibit rapid global expansion, often leveraging innovative capabilities, digitalization, and niche market strategies to compete internationally from an early stage (G. A. Knight & Cavusgil, 2004).

This line of research also focuses on both home and host market conditions. Most of the research emphasizes home country features or host country-specific context; therefore, this study considers home and host country market conditions by understanding the determinants of internationalization through the push-pull model. This model explains SME internationalization by identifying push factors (internal or external pressures that drive firms to expand abroad, such as market saturation or regulatory constraints) and pull factors (attractive opportunities in foreign markets, such as demand growth or favorable trade policies) (Wang et al., 2023). This framework is essential for understanding how born global firms navigate internationalization, particularly in emerging markets. The revision ensures a precise definition and contextual integration within our study.

Moreover, the internationalization of born global SMEs is under-researched, especially in the Indian context. Therefore, this context was chosen to study internationalization. This study builds on the established research on the internationalization of small and medium enterprises (SMEs), particularly born global firms (BGFs), while advancing the understanding of under-researched factors in the Indian context (G. A. Knight & Cavusgil, 2004; Narula, 2012). Unlike previous studies that predominantly focus on either home or host market factors (Fernandes et al., 2020; Lobo et al., 2023), this research employs a comprehensive push-pull model that integrates both external and firm-specific determinants to offer a multidimensional perspective on early internationalization (Dunning & Lundan, 2008).

A novelty aspect of this study lies in the development and application of the internationalization index (II), which quantifies the degree of international market reliance, allowing for a more nuanced comparison across firms and industries (Chakrabarty & Wang, 2012; Yang et al., 2020). Additionally, this research addresses the unique challenges faced by Indian SMEs, such as resource constraints and cultural proximity, which have not been extensively explored in existing international business literature (Behl et al., 2023; Shen et al., 2022). Despite the extensive research on SME internationalization, much of the literature focuses on firms in developed economies, leaving a significant gap in understanding the drivers of early internationalization in emerging markets (G. A. Knight & Liesch, 2016; Paul & Rosado-Serrano, 2019). Born global firms in developing economies face unique institutional, financial, and strategic challenges that differentiate their internationalization trajectories from their counterparts in advanced economies (Cavusgil & Knight, 2015). Existing models predominantly emphasize resource-rich firms, overlooking how constrained environments influence the push, pull, and firm-specific factors shaping international expansion (Rialp et al., 2005).

This study addresses this gap by developing an internationalization index that systematically evaluates these influencing factors in emerging markets, offering a comprehensive framework to assess the determinants of SME internationalization. By providing empirical evidence on born global firms operating in developing economies, the study contributes to both theoretical advancements in international business research and practical insights for policymakers and entrepreneurs seeking to enhance SMEs’ global competitiveness (Gabrielsson & Kirpalani, 2012).

2. Literature Review

Every business looks for the best way to enter a foreign market despite the uncertainty that comes with it. Due to the unpredictability of foreign markets, each business’s ideal entrance strategy is unique and depends on how various company and external market variables are weighted (Hashai & Almor, 2004). According to Shen et al. (2022), foreign market entrance mechanisms (Shen et al., 2022) are a structural arrangement that enables a company to do business internationally. Bose et al. (2024) distinguish between different entry modes based on their characteristics. It is also crucial to remember that, depending on the foreign markets they want to enter, many businesses decide to internationalize by using a mix of entry strategies concurrently or at separate points. Global firms/companies still need to be thoroughly researched in this context. Researchers have noted evidence indicating a growing prevalence of numerous forms of communication instead of separate unique modes (Benito et al., 2011, 2015; G. A. Knight & Cavusgil, 2004).

2.1. Early Internationalization in Born Global Firms

Practically speaking, two primary theoretical models have dominated research on the internationalization of new businesses. The first model focuses on the internationalization process hypothesis, initially introduced in early research (Bai & Johanson, 2018; Johanson & Mattsson, 1988; Johanson & Vahlne, 1977, 2015). The second is the international new ventures model, initially put out by McDougall et al. (2003) and McDougall et al. (1994). This model was utilized in this research, as there is a need to test measures of born global firms’ internationalization. The previous model was well-researched and gradually became outdated (Surdu et al., 2021), which will have only theoretical relevance in the coming decades. With the advancements in information technology and faster communication and transportation channels, the born global phenomenon will be a new model of entry into the international market. Therefore, there is a need to validate the antecedents of the global phenomenon of birth.

The notion of the internationalization process states that businesses progressively expand into new markets and allocate resources to the growth of their export-oriented operations. According to Bai and Johanson (2018), the process thus happens in phases, with businesses first establishing themselves locally before entering international markets. Conversely, according to the new international ventures’ paradigm, some emerging SMEs internationalize rapidly, exporting almost immediately to far-off markets. Consequently, many companies join international commerce nearly immediately rather than gradually after gaining expertise in the home market. A corpus of writing on the issues with early internationalization has been produced by the increasing “new international ventures”.

Important insights on the internationalization of new business are also provided by empirical evidence from Bruneel et al. (2010), which demonstrates that younger firms can make up for their lack of experience at the firm level through inter-organizational relationships (vicarious learning) and congenital learning, which is learning based on prior management team experiences. Learning via a network is the most prevalent kind of vicarious learning covered in conceptual and empirical research. As a result, liberty in decision-making is essential to success, even though they can mitigate the disadvantages of being foreign through networks or the global experience of their management team and staff. Therefore, funding and a willingness to take on risk are necessary to implement an internationalization plan. Entrepreneurs must first evaluate the available funding options before determining how best to fund the internationalization process. Moen et al. (2022) assert that marketing capabilities are a fundamental determinant of international market performance for both born-global and non-born global firms.

Selecting among the many sources is a challenging task. Pacheco and Tavares (2017) state, “A lack of financial resources can seriously impede SMEs’ international development, as it hinders them from making the necessary investments to enhance their exporting activities”. In the process of internationalization, the size of the firm is another important consideration (Clark et al., 1997). Most of the time, businesses are only able to grow in border nations due to resource restrictions that restrict their options for new markets (Fernandes et al., 2020). According to the business, resource scarcity and cultural closeness among bordering nations are advantageous and complementary elements for these regions’ internationalization (Cavusgil & Knight, 2015; G. A. Knight & Liesch, 2016; Madsen, 2014).

2.2. Pull Factors Among Born Globals (PLFs)

Regarding the factors that drive internationalization for businesses or the reasons that can spur a company’s desire or decision to do so, we define determinants as the motivational elements that drive businesses to internationalize (Huang & Hsieh, 2013; McCormick & Somaya, 2020). Numerous writers have endeavored to delineate those factors, emphasizing the significance of comprehending the established connections between the internal attributes of the organization (Magnani & Zucchella, 2019) and the external milieu (Narula, 2012) in conjunction with the disparate tactics employed to target external markets (Falahat et al., 2018). Three phases, as outlined by Douglas and Craig (2010), determine the company’s internationalization process. In regard to the polarization between internal aspects, Neto et al. (2020) and Fernandes et al. (2020) stress the managers’ worldwide perspective and attitude, organizational dynamics, and change management practices. Organizational dynamics, core competencies, market accessibility (closeness to customers), corporate integrity (capacity to act swiftly, nimbly, or dependably), product functionality, and capacity to learn and adjust to new procedures and organizational history, as well as any current issues, are taken into account (de Souza & Olive-Tomas, 2020). The techniques of engagement and education, negotiation and agreements, force and manipulation, and education and communication are inherent in change management.

Moghaddam et al. (2014), drawing on Dunning and Lundan’s (1998) model, affirm that there are four incentives for internalization: These resources may be scarce or non-existent in the country of origin, necessitating foreign investment; on the other hand, market-seeking refers to the desire of the company, which is typically a multinational enterprise, to be present in specific markets and offer goods and services to them. Additionally, there is a duty to follow suppliers and customers when they go global or present where rivals are. Multinational corporations prioritize efficiency-seeking to maximize revenues from their investments in overseas markets or more efficient supply structures. Examples include risk diversification, the need to identify global variations by deducting benefits, and cutting expenses associated with transportation, communication, and coordination. In terms of strategic asset-seeking, multinational corporations always seek to take advantage of or create advantages from market inefficiencies. They may accomplish long-term goals by acquiring tangible assets (Fernandes et al., 2020). The factors listed by Taylor et al. (2021) include having a partner in the foreign market or having an agent enter it, being close to the foreign market, lowering risk, cutting expenses, and using economies of scale and less restrictive laws and government incentives. The “dragging process”, wherein some businesses live in the nations where they are created to follow their clientele, is another factor contributing to internationalization (Carneiro et al., 2022).

2.3. Push Factors Among Born Globals (PUFs)

These are the things that the business owner acknowledges as the catalysts for the internationalization plan, that is, the things that made it possible for his enterprise to expand internationally or for it to expand its activities internationally. Inciting factors are the qualities the business has that others may not know but are essential to its ability to become global (Calvo & Villarreal, 2019). According to network theory, a firm’s location within the network will determine the range of possibilities and restrictions it faces, which will, in turn, influence the tactics it develops. According to Rezvani et al. (2019), people and firms in the network are granted more information about business opportunities, potential markets, etc., and have more possibilities to make use of such information the greater their power (knowledge, financial resources, etc.). According to Johanson and Mattsson (1988), these connections—both official and informal—significantly influence market choice and entrance strategy as they make it simple to spot and seize fresh chances. In the opinion of Carneiro et al. (2022), cooperation networks are unquestionably beneficial to a company’s competitiveness and have developed into a crucial instrument for assisting SMEs in their internationalization. According to Henriques and Thiel (2000), potentially contentious connections and disparate interests are seen as cooperative alliances centered on internationalization as a shared objective. Due to their lack of financial, technical, and human resources, Dos Santos and Guimarães-Iosif (2013) and Moya-Martínez and Pozo-Rubio (2021) contend that networks are even more crucial for SMEs for them to be able to internationalize their operations independently. These companies’ ability to compete in the global market is probably going to increase with their integration into a network. Joining a network offers access to a wealth of financial, technical, and—possibly—more crucial information about the external market, lowering the dangers associated with psychological remoteness.

Fernhaber and Li (2013) offered an alternative perspective on the significance of knowledge in network theory. These writers provide an alternative interpretation of the theory consistent with the so-called attention-based viewpoint. According to Casallas et al. (2007) and other scholars, the existing networks play a significant role in enhancing a company’s knowledge base, providing the foundation for identifying and appreciating global prospects. According to the so-called “limited rationality” of the attention-based view (Ardito et al., 2021; Fernhaber & Li, 2013), despite the possibility of multiple external sources of international exposure, various network relations can help entrepreneurs focus on the foreign opportunities that are best suited for their particular firm’s circumstances. The viewpoint presented here is validated by Bai and Johanson (2018).

According to Bembom and Schwens (2018), “the literature reveals that network contacts help early internationalization overcome resource deficits (e.g., by providing financial capital … and to access knowledge of foreign markets” (p. 01) in addition to giving them access to their first foreign markets (Bai & Johanson, 2018; Hashai & Almor, 2004).

Yayla et al. (2018) highlight that different organizations face different degrees of uncertainty and possible dangers when it comes to internationalization, depending on a range of resources and competencies as well as economic and competitiveness variables. Being proactive, taking chances, using resources, being innovation-focused and opportunity-driven, and being risk-takers may only be effective to a certain extent in these circumstances, which also impact internationalization. Additionally, verifying the internationalization considerations efforts is necessary, i.e., reducing the perceived risks relative to the perceived gains. Stated differently, sufficient validation efforts support risk/reward calculations (Crick et al., 2020).

Since exports are thought to be the most often employed internationalization strategy, “the contribution of exports to firm growth through sales increase is straightforward” (Pacheco, 2019, p. 98). However, examining other crucial elements in this process, such as the drivers and incentives of entrepreneurs, should be included in the study of internationalization processes and their success, regardless of their mode. These measures should be established through the lens of many theories, including resource-based, organizational learning, and industrial organization theories (Pacheco, 2019). Therefore, many antecedents were identified and narrowed down to those closely related to the sample firms.

2.4. Recent Developments in Born Global Internationalization

In recent years, scholars have significantly advanced the understanding of born global firms by investigating emerging determinants of rapid internationalization. Research by Zhang et al. (2022) emphasizes the importance of institutional distance in determining entry strategies, with variations in institutional frameworks across markets influencing both opportunities and challenges for early-stage internationalization. Similarly, Lobo et al. (2023) demonstrate that resource capabilities, such as dynamic absorptive capacity, enhance the competitiveness of born global firms by facilitating faster integration into global value chains. Moreover, Behl et al. (2023) highlight how digital transformation has become a pivotal factor, enabling firms to leverage technological innovation for market entry. Digital platforms, in particular, have been shown to reduce transaction costs, thereby accelerating internationalization (Ardito et al., 2021). The role of networks and relational capital in turbulent environments has also gained renewed attention, with findings suggesting that strong relational ties can mitigate risks associated with foreign market entry (Yayla et al., 2018; Taylor et al., 2021). These studies underscore the evolving landscape of international business and the need for entrepreneurial firms to adapt their strategies to both external and internal shifts. Such insights offer a contemporary lens through which to interpret the findings of this study, ensuring greater relevance to ongoing scholarly discourse.

2.5. Internal Firm-Specific Factors (IFCs)

Internal agents are the company’s managers and people in charge. They make the majority of the decisions about the company’s international involvement, taking into account factors like government and associative incentives, might be taken into consideration as external agents of internationalization; for the majority of enterprises, they have a favorable influence at the beginning of internationalization (Vinueza & Jaramillo, 2016). However, import country rules and the availability of market data might operate as a conditioning element in this process (Efrat & Shoham, 2012). The company’s external agents may also include the overall state of the economy, marketing circumstances, the size of the home market, and the company’s closeness to other markets (Fan & Phan, 2007).

The success of the internationalization process depends on several factors, including factors such as “firm-specific advantages and country-specific factors, e.g., firm size, industry, firm age, the experience gathered in a foreign market, R&D investments, and institutions in the country of origin” (Barłożewski & Trąpczyński, 2021, p. 86), should be taken into consideration for the internationalization process. Myriad researchers (Behl et al., 2023; Kalinic & Brouthers, 2022; Martin & Javalgi, 2018; Riddle & Gillespie, 2003; Zalan, 2018) indicate that an organization’s performance during the internationalization process is influenced by the entrepreneurial initiative and traits of the entrepreneur and his staff. Santhosh (2020) highlights upper management’s significance and attributes, including age, educational background, foreign language proficiency, worldwide experience, network connections, technology innovation, and proactive attitude.

In light of this, it is pertinent to analyze how thriving businesses are performing in terms of internationalization, taking into account not only financial metrics but also the underlying causes of internationalization and the elements that entrepreneurs believe contribute to it. Therefore, the hypotheses were framed and presented as follows:

H1.

Push factors influence a company’s early internationalization regarding internal market features.

H2.

The pull factors influence a company’s early internationalization in terms of the features of the external market.

H3.

The internal firm-specific factors have a favorable relationship with early internationalization.

3. Conceptual Model

The conceptual model of research is a systematic arrangement of independent and dependent variables used in the research. The model is given in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of research.

4. Methods

The data were collected between May 2023 and January 2024. Young enterprises were included in the sample, and questionnaires were sent to gather data. Our study will include 280 businesses of all sizes and industries, from whom the data required for all the variables chosen in this research could be obtained. We concentrated our research on born global firms; therefore, companies established after the year 2000 and that had any form of international operations were chosen for data collection. The list was obtained from the business standard new venture list for 2023, published annually. We want to develop a relationship between internationalization and its drivers and inciting variables based on the literature research. We model three distinct determinants of internationalization, as shown by Miller et al. (2016) and Pacheco (2019). The responses comprised 280 managers working in companies that have internationalized and are of varying sizes and sectors. The average age of these enterprises is approximately 23 years. They have been internationalizing for an average of 22 years. The industrial sector comprises half of the sample’s companies. More than 90% of the companies started internationalization from the first year of their inception. The average experience in the present position of the respondents was 7.5 years.

A sample of 500 Indian companies was selected for the study. Along with the study questionnaire, invitations were given out. Various companies provided 300 replies, translating to a response rate of 59.58% of the original sample. There were 280 full surveys in the end since 20 replies were incomplete. Biases in response and non-response were identified. By comparing the initial and late respondents, non-response bias was ruled out since the number of late respondents was comparable to that of non-respondents. Response bias was assessed using exploratory factor analysis (EFA).

A Likert scale from strongly agree to disagree was used to assess the scale. Efforts were made throughout the data analysis to reduce common method bias (CMB). Numerous studies where data are gathered from a single source or via self-administered questionnaires have this inaccuracy. A cover letter was created to ensure the confidentiality of the replies and the privacy of the identities. Unclear statements were avoided, and several color schemes were used to help the respondents distinguish between the various notions. In this way, the constructs were labeled correctly, and a straightforward research tool was created to reduce CMB (Hair et al., 2017). In Table 1, we present the description of items used in this study. In addition, the measurement validity was evaluated, and an attempt was made to familiarize the respondents with the study tool. All respondents were informed of the rationale for the selection process, and participation’s benefits and associated hazards were also explained (Malhotra, 2020). In Table 2, to rule out the issue of common method bias, principal component analysis was performed on all the research scales, and it was found that nine factors emerged, ensuring the absence of common method bias in this research.

Table 1.

Description of items.

Table 2.

Total variance explained.

The data were collected on the above scales and analyzed using Lisrel 9.0 and SPSS 26.0. These responses were the primary focus of the specific case under investigation.

5. Results

The measures of normality of data, such as skewness and kurtosis, were also measured for all the study scales. The values of skewness should be between +2 and −2; however, the values of kurtosis can range between +3 and −3. In this research, the values are under acceptable ranges. Therefore, the data are usually appropriately distributed for further analysis. The results are given in Table 3.

Table 3.

The normality of the data.

5.1. Methods of Data Analysis

First, the measurement model was evaluated using SEM (Dash & Paul, 2021) when the analysis was completed. Numerous tests were run as part of the measurement model evaluation procedure. The first step in this process was to find the unidimensionality, validity, and reliability of the approach used to do a structural equation modeling (SEM) study. SEM is a statistical method that may examine intricate theories about the connections between many variables. It is crucial to evaluate the measurement model—a model of how the variables are measured—before using SEM analysis. Lisrel 8.80, a program for evaluating primary data gathered for research scales, was used in this study to conduct SEM. This method works well for less than large sample sizes and complicated modeling involving more than two independent variables (Collier, 2020). Two techniques were used to determine the appropriate sample size. The creators of Lisrel 8.80, (Jöreskog & Sörbom, 1990), support the first approach, which applies the following formula:

where (k) = 4 is the number of variables.

k(k − 1)/2,

A minimum sample size of 6 is required, and a sample size of 280 instances is sufficient. Second, out of 280 total sample items, 3 had an effect size of 0.10, an error probability of 0.05, and a total sample size of 280. The computed sample power exceeded 80%, satisfying the need to verify that the modeling may be completed quickly (Malhotra, 2020).

5.2. Measurement Model

Several tests were run throughout the assessment process to ensure the measurement model was suitable for the data. The evaluation of unidimensionality is usually one of the initial tests carried out. The notion of unidimensionality states that all of the variables being assessed ought to be gauging the same underlying construct or idea. Put differently, there should be a consistent relationship between the variables. Factor analysis, or parallel analysis, is often employed to evaluate the unidimensionality. When evaluating the measurement model, an evaluation of its validity and reliability is also often conducted. Measurement consistency is referred to as reliability, and it is often evaluated by looking at the internal consistency of the variables, such as Cronbach’s alpha. Conversely, validity denotes the degree to which the variables measure the intended outcomes. Many techniques, including construct validity, criterion-related validity, and content validity, may be used to evaluate the validity. It is important to remember that although SEM is an effective technique, it is flexible. For instance, it assumes that the measurement errors are independent and that the data are standard. The normality of data was initially established. As a result, it is critical to thoroughly assess the model’s assumptions and ensure the data complies with the method’s specifications. The range of path values, Cronbach’s alpha, t-values, and AVE are presented in the table below. For model fit, GFI values were assessed.

It was discovered that every research construct had a loading value greater than 0.50. Apart from this, Cronbach’s alpha was used to guarantee internal consistency. For every study construct, the alpha value exceeded the minimum requirement of 0.70, with a maximum value of 0.95 (Hair et al., 2017). The acceptable criterion of 0.50 was met by the AVE, which was more than 0.50 for every research construct (refer to Table 4). Thus, all scales were pretested, which is the process of analyzing the study variables and the outcomes using a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). All of the study constructs had a loading value larger than 0.50, according to the CFA findings shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Path values, Cronbach’s alpha, t-values, and AVE for the measurement model.

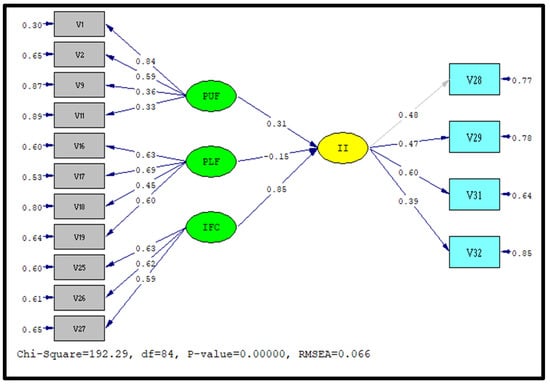

5.3. Evaluation of Structural Model

After assessing the response received, the study delves into establishing the data’s normality and the measurement model’s evaluation. Once the measurement model was finalized, the structural model was estimated. The hypothesis was accepted/rejected based on estimates obtained from structural model assessment. The structural model estimates the influence of independent variables and all dependent variables. The structural model was assessed, and the estimates are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Structural model.

The estimated value from pull factors (PLFs) towards the internationalization index (II) was significant (0.31 *). Therefore, the hypothesis was accepted. Similarly, push factors (PUFs) also have an impact on the internationalization index (II) (0.15 **) developed in this study. Apart from these two, internal factors/firm-specific characteristics (IFCs) strongly influence the internationalization index compared to push and pull factors (0.85 ***). The conclusions based on these findings were discussed in the light of the literature and presented in the next section.

6. Discussion

Our findings validate and extend the existing literature by demonstrating that internal firm-specific factors play a more significant role in early internationalization than push or pull factors, particularly within the context of emerging economies (Falahat et al., 2018; Paul & Gupta, 2014). This contrasts with earlier research that emphasizes external market conditions as primary drivers (G. A. Knight & Liesch, 2016; Huang & Hsieh, 2013). This study further distinguishes itself by incorporating a sample of 280 Indian SMEs, thereby addressing the contextual gap highlighted in international business research, where studies on emerging market firms remain limited (Narula, 2012; Lobo et al., 2023). The results underscore the importance of entrepreneurial capabilities, risk management, and international networks, which are less prevalent in traditional models of SME internationalization (Fernhaber & Li, 2013; Crick et al., 2020). By providing a refined conceptual model and empirical evidence, this study contributes to both theoretical and practical advancements, offering strategic insights for entrepreneurs and policymakers aiming to enhance global competitiveness (Madsen, 2014; Dunning & Lundan, 2008). It was ascertained from the data that H01 was accepted, implying the influence of push factors with early internationalization, i.e., usually, factors and features of the home market were among the influencers of internationalization. It was also suggested that the first three factors significantly emphasize the need to explore markets and reduce and diversify risks. This notion was put forth by Dunning and Lundan’s (1998) model and supported by Dunning and Lundan (2008). The results of the tests for hypothesis 2 indicate a positive correlation between internationalization performance and pull factors, i.e., internationalization determinants associated with foreign market characteristics. This correlation is particularly significant for new prospective markets. A combined model was assessed that combines the features of the local and international markets and firm characteristics. The results show that gaining new clients and markets and lowering or diversifying risks are positively and significantly correlated. Once again, our findings are consistent with those of Dunning and Lundan (2008) regarding efficiency-seeking motives.

Finally, we examine the influence of internal firm-specific factors (IFCs)—these are the internal triggers of the internationalization strategy of the firm; these are the factors that allowed the company to internationalize its operations: particular employee abilities, personnel experience abroad, strong inclination towards entrepreneurship and risk-taking among key personnel and the management of the firm, formal and informal contact networks, geographic closeness to new markets, and both cultural and linguistic proximity. The significance of these factors was also observed in the works of Lobo et al. (2023) and Paul and Gupta (2014). Early internationalization refers to firms that expand into foreign markets within a short period after inception, typically within the first three years of operation, as seen in born global firms (G. A. Knight & Cavusgil, 2004). These firms exhibit proactive international strategies, leveraging niche market opportunities, digitalization, and network relationships to compete globally from an early stage (Rialp et al., 2005). In contrast, later internationalization follows a gradual, staged process, where firms initially focus on domestic growth before expanding internationally in incremental steps, consistent with Uppsala internationalization theory (Johanson & Vahlne, 2015). This differentiation is essential in understanding the factors influencing internationalization speed, strategic decision-making, and market entry modes.

According to Barłożewski and Trąpczyński (2021), a company’s membership in the industrial sector also significantly and favorably impacts these three antecedents of early internationalization. These factors determine the early internationalization process, representing the company’s characteristics and initiating the internationalization strategy; this study helped us determine which factors entrepreneurs should prioritize and strengthen to achieve better performance in the internationalization process. The research also wants to aid in identifying the elements that will enhance early internationalization and try to draw the attention of young entrepreneurs as they begin the internationalization process. This research also prioritizes the factors responsible for early internationalization. It is observed that firm characteristics have the strongest influence on the early internationalization of firms. These findings are pertinent for the practitioners and researchers working in this area. Based on the study’s findings, firms aiming for early internationalization should focus on leveraging digital platforms, developing strong international networks, and adopting market differentiation strategies to gain a competitive edge (Cavusgil & Knight, 2015). Additionally, accessing government support programs, securing strategic partnerships, and enhancing innovation capabilities are crucial in overcoming market entry barriers and sustaining global operations (Rialp et al., 2005). These strategies align with the determinants identified in this study, providing actionable insights for entrepreneurs and policymakers.

7. Implications of the Study

This study contributes to international business literature by offering a structured approach to assessing the determinants of early internationalization, particularly in emerging markets. By developing an internationalization index, the research advances the theoretical understanding of born global firms and their expansion strategies. Practically, the findings provide entrepreneurs and SMEs with insights into key success factors for global market entry, emphasizing the role of networking, innovation, and institutional support. Additionally, policymakers can leverage these insights to design targeted policies that enhance SME competitiveness, reduce internationalization barriers, and foster an enabling business environment.

8. Conclusions

A significant obstacle for most small and medium-sized businesses is entering a foreign market. Looking at who, when, how, and why businesses internationalize is crucial. With the more integrated market research on reasons for internationalization and internalization, performance is becoming increasingly relevant in the literature. However, the analysis of financial indicators alone should not be the only consideration in the study of internationalization processes and performance; instead, the fundamental causes of companies’ internationalization, as well as the factors that entrepreneurs believe stimulate internationalization, should be taken into account. This study examines the link between the elements that define and trigger the internationalization process of a firm and its success in it. Three aspects of internationalization were examined: push, pull, and internal firm-specific factors. Three hypotheses are tested in this process: H1: the push factors influence a company’s early internationalization concerning internal market features; H2: the pull factors influence a company’s early internationalization concerning the features of the external market; and H3: the internal firm-specific factors have a favorable relationship with early internationalization. Overall, the data demonstrate that the various variables exhibit the anticipated signals and enable us to verify the various hypotheses.

Limitation

This research does, however, have many things that could be improved. One disadvantage of using the questionnaires, a popular method, is that there needed to be more responses in survey-based research, which was a setback. Therefore, the findings cannot be generalized. Additional gathering is necessary to expand the study’s impact. However, the literature offers several strategies that might be investigated, along with the potential to include additional factors that we will look at in further research in this domain. Apart from these, the study uses a single cross-sectional design. However, in these kinds of research, where newer theories are tested to replace the older ones, it would be more appropriate. These issues can be dealt with in future research. Also, researchers may perform different forms of systematic literature reviews (Fakhar et al., 2023; Khan et al., 2023, 2025a, 2025b; Khan & Azam, 2023; Rashid et al., 2025) on the topics covered in this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.K.C., S.S. and A.H.M.; methodology, A.I., M.F.M. and N.K.; software, S.K.C., A.I., M.F.M. and N.K.; validation, A.I., M.F.M. and N.K.; formal analysis, S.K.C., A.I., M.F.M. and N.K.; investigation, A.I., M.F.M. and N.K.; resources, S.K.C., S.S. and A.H.M.; data curation, A.I., M.F.M. and N.K.; writing—original draft preparation, S.K.C., S.S. and A.H.M.; writing—review and editing, S.S. and A.H.M.; visualization, S.S. and A.H.M.; supervision, S.K.C., S.S. and A.H.M.; project administration, S.K.C., S.S. and A.H.M.; funding acquisition, S.K.C., S.S. and A.H.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

No experimental or physical activity was carried out. Although there was intellectual participation, no ethical approval was required or taken.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ardito, L., Raby, S., Albino, V., & Bertoldi, B. (2021). The duality of digital and environmental orientations in the context of SMEs: Implications for innovation performance. Journal of Business Research, 123, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arpa, C., Tiernan, S., & O’Dwyer, M. (2012). Entrepreneurial orientation, market orientation and internationalisation in born global small and micro-businesses. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 16(4), 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, W., & Johanson, M. (2018). International opportunity networks. Industrial Marketing Management, 70, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barłożewski, K., & Trąpczyński, P. (2021). Internationalisation motives and the multinationality-performance relationship: The case of Polish firms. Entrepreneurial Business and Economics Review, 9(2), 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behl, A., Kamboj, S., Sharma, N., Pereira, V., Salwan, P., Chavan, M., & Pathak, A. A. (2023). Linking dynamic absorptive capacity and service innovation for born global service firms: An organization innovation lens perspective. Journal of International Management, 29(4), 101044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bembom, M., & Schwens, C. (2018). The role of networks in early internationalizing firms: A systematic review and future research agenda. European Management Journal, 36(6), 679–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito, G. R. G., Petersen, B., & Welch, L. S. (2011). Mode combinations and international operations. Management International Review, 51(6), 803–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito, G. R. G., Petersen, B., & Welch, L. S. (2015). Towards more realistic conceptualisations of foreign operation modes. International Business Strategy: Theory and Practice, 40, 232–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bérard, C., & Delerue, H. (2010). A cross-cultural analysis of intellectual asset protection in SMEs: The effect of environmental scanning. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 17(2), 167–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bıçakcıoğlu-Peynirci, N. (2023). Internationalization of emerging market multinational enterprises: A systematic literature review and future directions. Journal of Business Research, 164, 114002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, T. K., Chew, T. C., Purohit, S., & Moser, R. (2024). International business entry modes and consumer ethnocentrism: A multi country perspective. Thunderbird International Business Review, 66(3), 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruneel, J., Yli-Renko, H., & Clarysse, B. (2010). Learning from experience and learning from others: How congenital and interorganizational learning substitute for experiential learning in young firm internationalization. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 4(2), 164–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, N., & Villarreal, O. (2019). Internationalization as process of value distribution through innovation: Polyhedral diagnosis of a ‘born global’ firm. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 34(3), 561–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canabal, A., & White, G. O. (2008). Entry mode research: Past and future. International Business Review, 17(3), 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, J., Moreira, A. A., & Sheng, H. H. (2022). Influences of foreign and domestic venture capitalists on internationalisation of small firms. BAR-Brazilian Administration Review, 19(1), e200105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casallas, R., González, O., & López, N. (2007). Dealing with scalability in an event-based infrastructure to support global software development. In Lecture notes in computer science (including subseries lecture notes in artificial intelligence and lecture notes in bioinformatics) (Vol. 4473, pp. 100–111). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavusgil, S. T., & Knight, G. (2015). The born global firm: An entrepreneurial and capabilities perspective on early and rapid internationalization. Journal of International Business Studies, 46(1), 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarty, S., & Wang, L. (2012). The long-term sustenance of sustainability practices in mncs: A dynamic capabilities perspective of the role of R&D and internationalization. Journal of Business Ethics, 110(2), 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, T., Pugh, D. S., & Mallory, G. (1997). The process of internationalization in the operating firm. International Business Review, 6(6), 605–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, J. E. (2020). Applied structural equation modeling using AMOS (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crick, J. M., Crick, D., & Chaudhry, S. (2020). Entrepreneurial marketing decision-making in rapidly internationalising and de-internationalising start-up firms. Journal of Business Research, 113, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyert, R. M., & March, J. G. (1965). A behavioral theory of the firm. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 60(309), 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, G., & Paul, J. (2021). CB-SEM vs PLS-SEM methods for research in social sciences and technology forecasting. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 173, 121092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, Y. S., & Olive-Tomas, A. (2020). International entrepreneurship in the video game industry in barcelona. In Cases on internationalization challenges for SMEs (pp. 99–128). IGI Global. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, A. V., & Guimarães-Iosif, R. M. (2013). The internationalization of higher education in Brazil: A marketing policy. Journal of Contemporary Issues in Education, 8(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, S. P., & Craig, C. S. (2010). Global marketing strategy: Perspectives and approaches. In Wiley international encyclopedia of marketing. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunning, J. H., & Lundan, S. M. (1998). The geographical sources of competitiveness of multinational enterprises: An econometric analysis. International Business Review, 7(2), 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunning, J. H., & Lundan, S. M. (2008). Multinational enterprises and the global economy (2nd ed.). Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Efrat, K., & Shoham, A. (2012). Born global firms: The differences between their short- and long-term performance drivers. Journal of World Business, 47(4), 675–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhar, S., Khan, F. M., Tabash, M. I., Ahmad, G., Akhter, J., & Al-Absy, M. S. M. (2023). Financial distress in the banking industry: A bibliometric synthesis and exploration. Cogent Economics & Finance, 11(2), 2253076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falahat, M., Knight, G., & Alon, I. (2018). Orientations and capabilities of born global firms from emerging markets. International Marketing Review, 35(6), 936–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falahat, M., Senik, Z. C., Lee, Y. Y., & Migin, M. W. (2023). The impact of ecosystem on the speedy internationalisation of born global firms in emerging markets. European Journal of International Management, 21(3), 509–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, T., & Phan, P. (2007). International new ventures: Revisiting the influences behind the ‘born-global’ firm. Journal of International Business Studies, 38(7), 1113–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, C. I., Ferreira, J. J., Lobo, C. A., & Raposo, M. (2020). The impact of market orientation on the internationalisation of SMEs. Review of International Business and Strategy, 30(1), 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernhaber, S. A., & Li, D. (2013). International exposure through network relationships: Implications for new venture internationalization. Journal of Business Venturing, 28(2), 316–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrielsson, M., & Kirpalani, V. H. M. (2012). Handbook of research on born globals (pp. 1–417). Edward Elgar. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Babin, B. J., & Krey, N. (2017). Covariance-based structural equation modeling in the Journal of Advertising: Review and recommendations. Journal of Advertising, 46(1), 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halawa, A. (2018). Acculturation of halal food to the american food culture through immigration and globalization: A literature review. Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Studies, 5(2), 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashai, N., & Almor, T. (2004). Gradually internationalizing ‘born global’ firms: An oxymoron? International Business Review, 13(4), 465–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriques, E. B., & Thiel, J. (2000). The cultural economy of cities: A comparative study of the audiovisual sector in Hamburg and Lisbon. European Urban and Regional Studies, 7(3), 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitt, M. A., Ireland, R. D., & Rowe, G. W. (2005). Strategic leadership: Strategy, resources, ethics and succession. In Handbook on responsible leadership and governance in global business (pp. 19–41). Elgaronline. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H. Y., & Hsieh, M. H. (2013). The accelerated internationalization of born global firms: A knowledge transformation process view. Journal of Asia Business Studies, 7(3), 244–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johanson, J., & Mattsson, L. (1988). Internationalisation in industrial systems—A network approach. In Knowledge, networks and power (pp. 287–314). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johanson, J., & Vahlne, J. E. (1977). The internationalization process of the firm—A model of knowledge development and increasing foreign market commitments. Journal of International Business Studies, 8(1), 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johanson, J., & Vahlne, J. E. (2015). The Uppsala internationalization process model revisited: From liability of foreignness to liability of outsidership. International Business Strategy: Theory and Practice, 40, 33–59. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, G., & Pitelis, C. (2015). Entrepreneurial imagination and a demand and supply-side perspective on the MNE and cross-border organization. Journal of International Management, 21(4), 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jöreskog, K. G., & Sörbom, D. (1990). Model search with TETRAD II and LISREL. Sociological Methods & Research, 19(1), 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinic, I., & Brouthers, K. D. (2022). Entrepreneurial orientation, export channel selection, and export performance of SMEs. International Business Review, 31(1), 101901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayacı, A. (2021). Entrepreneurship in cross-border investments: Cases of emerging multinationals’ strategic asset-seeking internationalisation. In Contemporary entrepreneurship issues in international business (pp. 115–138). World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F. M., Anas, M., & Uddin, S. M. F. (2023). Anthropomorphism and consumer behaviour: ASPAR-4-SLRprotocol compliant hybrid review. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 48(1), e12985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F. M., & Azam, M. K. (2023). Chatbots in hospitality and tourism: A bibliometric synthesis of evidence. Journal of the Academy of Business and Emerging Markets, 3(2), 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F. M., Khan, A., Ahmed, S. S., Naz, A., Salim, M., Zaheer, A., & Rashid, U. (2025a). The machiavellian, narcissistic, and psychopathic consumers: A systematic review of dark triad. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 49(2), e70018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F. M., Uddin, S. M. F., Anas, M., Kautish, P., & Thaichon, P. (2025b). Personal values and sustainable consumerism: Performance trends, intellectual structure, and future research fronts. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 24(2), 734–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, A. N., Danis, W. M., & Cavusgil, S. T. (2012). International entrepreneurship research in emerging economies: A critical review and research agenda. Journal of Business Venturing, 27(2), 266–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, G., & Khan, H. (2024). Born global firms. In Encyclopedia of international strategic management (pp. 14–17). Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, G. A., & Cavusgil, S. T. (2004). Innovation, organizational capabilities, and the born-global firm. Journal of International Business Studies, 35(2), 124–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, G. A., & Liesch, P. W. (2016). Internationalization: From incremental to born global. Journal of World Business, 51(1), 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. (2017). Born global firms’ growth and collaborative entry mode: The role of transnational entrepreneurs. International Marketing Review, 34(1), 46–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo, C. A., Fernandes, C., Ferreira, J., Veiga, P. M., & Gerschewski, S. (2023). The determinants of international performance for family firms: Understanding the effects of resources, capabilities, and market orientation. Entrepreneurship Research Journal, 13(3), 773–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, T. K. (2014). Internationalization processes of professional service firms. In Research handbook on export marketing (pp. 132–144). Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnani, G., & Zucchella, A. (2019). Coping with uncertainty in the internationalisation strategy: An exploratory study on entrepreneurial firms. International Marketing Review, 36(1), 131–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N. K. (2020). Marketing research: An applied orientation (7th ed.). Pearson Education Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Manohar, A., Lioliou, E., Prevezer, M., & Saridakis, G. (2025). Explaining differences in internationalization between emerging and developed economy born global firms: A systematic literature review and the way forward. International Journal of Management Reviews, 27(1), 34–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, S. L., & Javalgi, R. G. (2018). Epistemological foundations of international entrepreneurship. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 14(3), 671–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, M., & Somaya, D. (2020). Born globals from emerging economies: Reconciling early exporting with theories of internationalization. Global Strategy Journal, 10(2), 251–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDougall, P. P., Oviatt, B. M., & Shrader, R. C. (2003). A comparison of international and domestic new ventures. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 1(1), 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDougall, P. P., Shane, S., & Oviatt, B. M. (1994). Explaining the formation of international new ventures: The limits of theories from international business research. Journal of Business Venturing, 9(6), 469–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S. R., Lavie, D., & Delios, A. (2016). International intensity, diversity, and distance: Unpacking the internationalization–performance relationship. International Business Review, 25(4), 907–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moed, H. F., Glänzel, W., & Schmoch, U. (Eds.). (2005). Handbook of quantitative science and technology research. Springer Science + Business Media, Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moen, Ø., Falahat, M., & Lee, Y. (2022). Are born global firms really a “new breed” of exporters? Empirical evidence from an emerging market. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 20(1), 157–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghaddam, K., Sethi, D., Weber, T., & Wu, J. (2014). The smirk of emerging market firms: A modification of the dunning’s typology of internationalization motivations. Journal of International Management, 20(3), 359–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya-Martínez, P., & Del Pozo-Rubio, R. (2021). The financing of SMEs in the Spanish tourism sector at the onset of the 2008 financial crisis: Lessons to learn? Tourism Economics, 27(7), 1323–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narula, R. (2012). Do we need different frameworks to explain infant MNEs from developing countries? Global Strategy Journal, 2(3), 188–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, A. R., de Sousa-Filho, J. M., Leocádio, Á. L., & Nascimento, J. C. H. B. D. (2020). Internationalization of cultural products: The influence of soft power. International Journal of Market Research, 62(3), 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwankwo, S., & Gbadamosi, A. (Eds.). (2020). Entrepreneurship marketing (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, L. (2019). Internationalization effects on financial performance: The case of Portuguese industrial SMEs. Journal of Small Business Strategy, 29(3), 97–116. [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco, L., & Tavares, F. (2017). Capital structure determinants of hospitality sector SMEs. Tourism Economics, 23(1), 113–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J., & Gupta, P. (2014). Process and intensity of internationalization of IT firms—Evidence from India. International Business Review, 23(3), 594–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J., & Rosado-Serrano, A. (2019). Gradual Internationalization vs Born-Global/International new venture models: A review and research agenda. International Marketing Review, 36(6), 830–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, U., Abdullah, M., Tabash, M. I., Khan, F. M., Naaz, I., & Akhter, J. (2025). Unlocking the synergy between capital structure and corporate sustainability: A hybrid systematic review and pathways for future research. International Journal of Organizational Analysis. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezvani, M., Lashgari, M., & Farsi, J. Y. (2019). International entrepreneurial alertness in opportunity discovery for market entry. Journal of Research in Marketing and Entrepreneurship, 21(2), 76–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rialp, A., Rialp, J., & Knight, G. A. (2005). The phenomenon of early internationalizing firms: What do we know after a decade (1993–2003) of scientific inquiry? International Business Review, 14(2), 147–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riddle, L. A., & Gillespie, K. (2003). Information sources for new ventures in the turkish clothing export industry. Small Business Economics, 20(1), 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riefler, P. (2012). Why consumers do (not) like global brands: The role of globalization attitude, GCO and global brand origin. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 29(1), 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santhosh, C. (2020). What affects the export entrepreneurship of SMEs? Review of International Business and Strategy, 30(2), 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B., Zhang, T., Xu, X., Chan, H., & Choi, T. (2022). Preordering in luxury fashion: Will additional demand information bring negative effects to the retailer? Decision Sciences, 53(4), 681–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surdu, I., Greve, H. R., & Benito, G. R. G. (2021). Back to basics: Behavioral theory and internationalization. Journal of International Business Studies, 52(6), 1047–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M., Jack, R., Madsen, T., & Alam, M. (2021). The nature of service characteristics and their impact on internationalization: A multiple case study of born global firms. Journal of Business Research, 132, 517–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinueza, E. J., & Jaramillo, E. (2016). Marketing internacional. INNOVA Research Journal, 1(1), 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L., Li, X., Zhu, H., & Zhao, Y. (2023). Influencing factors of livestream selling of fresh food based on a push-pull model: A two-stage approach combining structural equation modeling (SEM) and artificial neural network (ANN). Expert Systems with Applications, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A. M., & Shaw, G. (2011). Internationalization and innovation in tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(1), 27–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M. M., Li, T., & Wang, Y. (2020). What explains the degree of internationalization of early-stage entrepreneurial firms? A multilevel study on the joint effects of entrepreneurial self-efficacy, opportunity-motivated entrepreneurship, and home-country institutions. Journal of World Business, 55(6), 101114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yayla, S., Yeniyurt, S., Uslay, C., & Cavusgil, E. (2018). The role of market orientation, relational capital, and internationalization speed in foreign market exit and re-entry decisions under turbulent conditions. International Business Review, 27(6), 1105–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalan, T. (2018). Born global on blockchain. Review of International Business and Strategy, 28(1), 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W., He, X., Wang, T., & Wang, K. (2022). Institutional distance and the international market entry mode: A meta-analysis. Journal of International Management, 29(1), 100990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).