Analysis of Solidarity Mechanisms Affecting the Performance of Ethnic Minority Business Groups in Africa

Abstract

1. Introduction

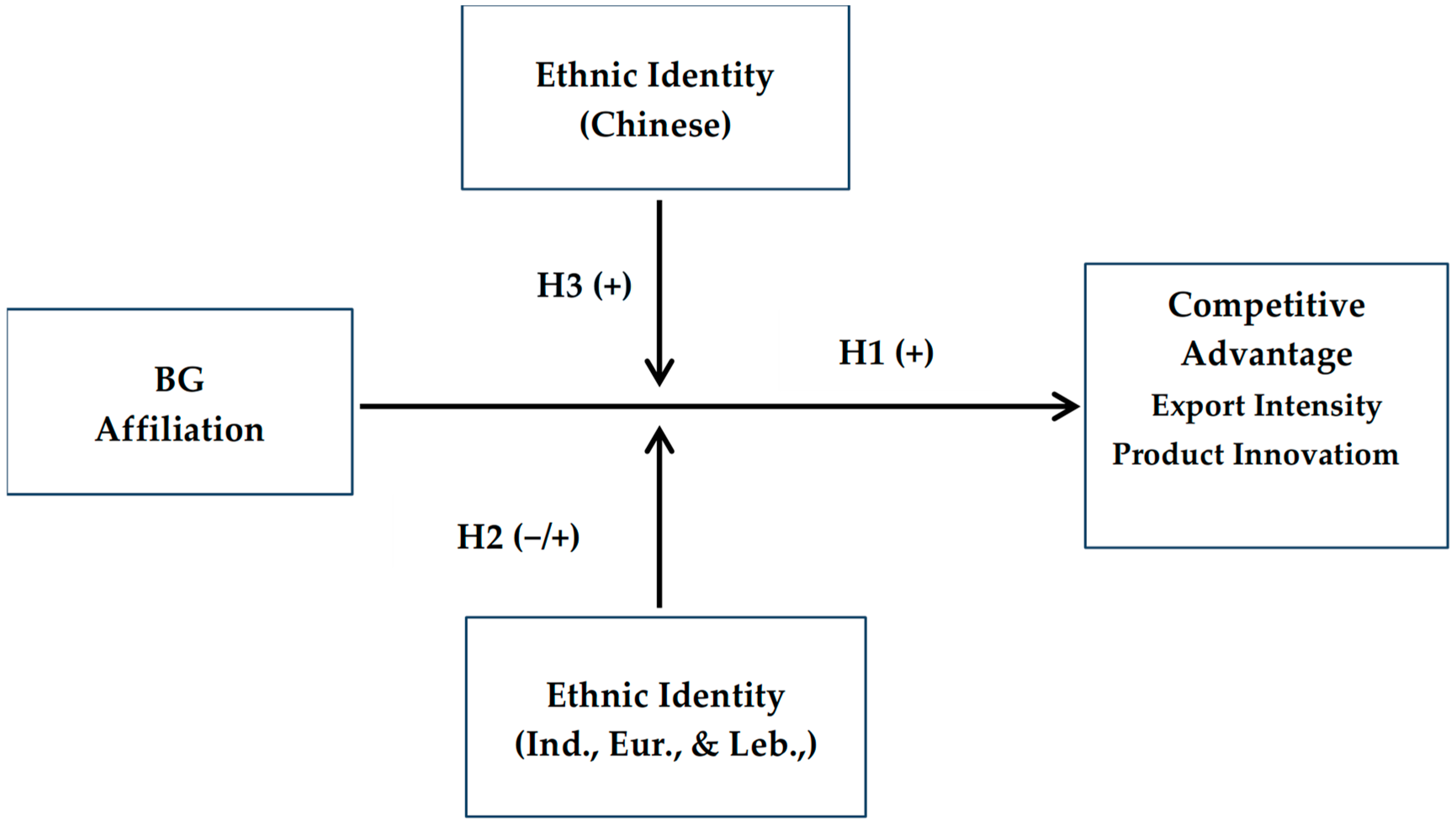

2. Context, Theory, and Hypotheses

2.1. Context

2.2. Business Groups and Competitive Advantage

2.3. Social Embeddedness in Ethnically Homogeneous Minority BGs

2.4. China’s BGs in Africa: Newcomer Exceptionalism

3. Methods

3.1. Data Source

3.2. Variables and Measurement

3.3. Analysis

| Export intensity = α + β BGA + β Control Variables + industry and time controls + ε | (1) |

Product Innovation = α + β BGA + β Control Variables + industry and time controls | (2) |

| + ε | |

Export intensity = α + β BGA + β African + β Indian + β Middle Eastern + β European | (3) |

| + β Asian + β Control Variables + industry and time controls + ε | |

Export intensity = α + β BGA + β African + β Indian + β Middle Eastern + β European | (4) |

| + β Asian + β BGA * African +/− β BGA * Indian +/− β BGA * Middle Eastern +/− β | |

| BGA * European + β BGA * Asian + β Control Variables + industry and time controls | |

| + ε | |

Product Innovation = α + β BGA + β African + β Indian + β Middle Eastern + β | (5) |

| European + β Asian + β Control Variables + industry and time controls + ε | |

Product Innovation = α + β BGA + β African + β Indian + β Middle Eastern + β | (6) |

| European + β Asian + β BGA * African +/− β BGA * Indian +/− β BGA * Middle | |

| Eastern +/− β BGA * European + β BGA * Asian + β Control Variables + industry and | |

| time controls + ε |

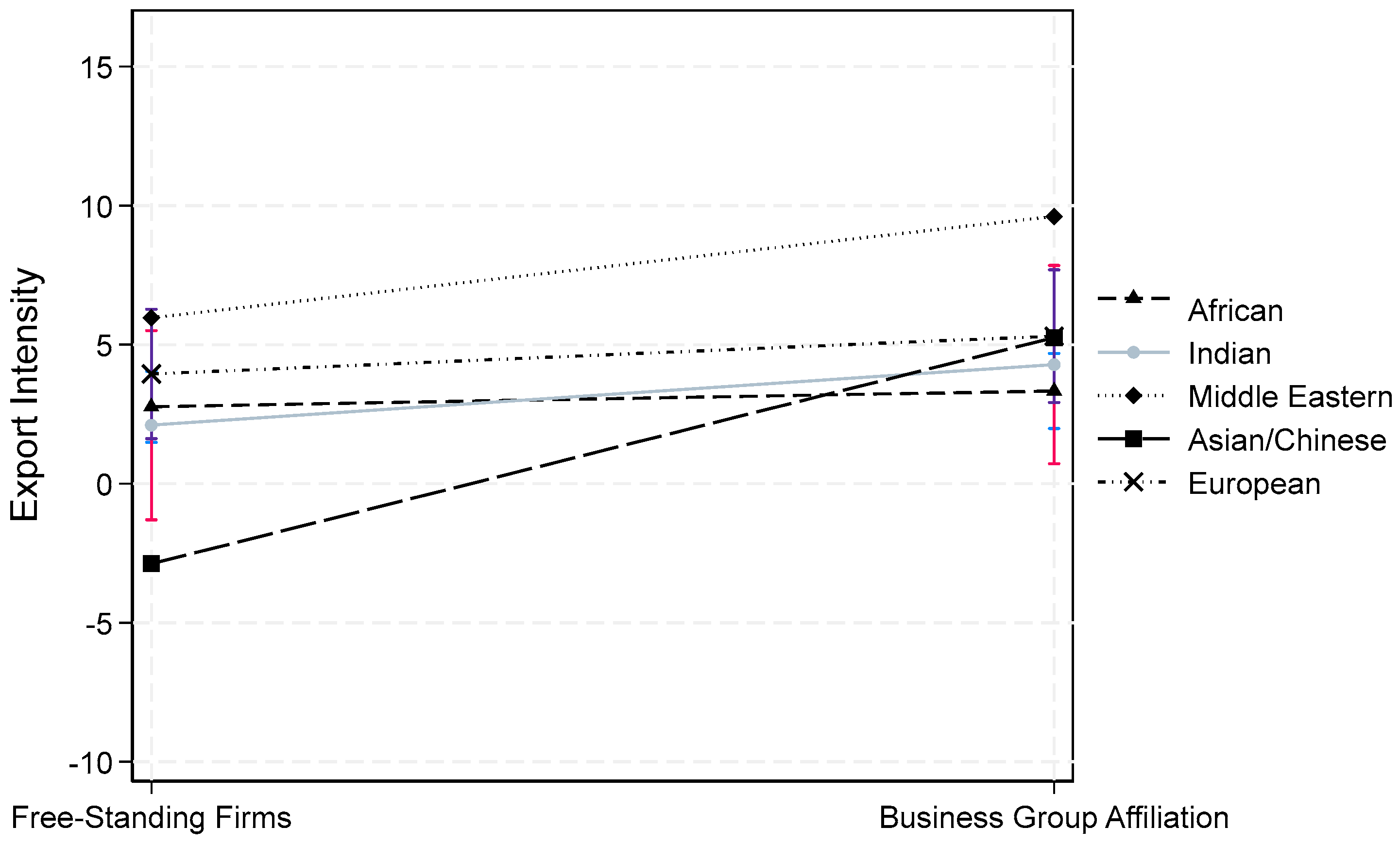

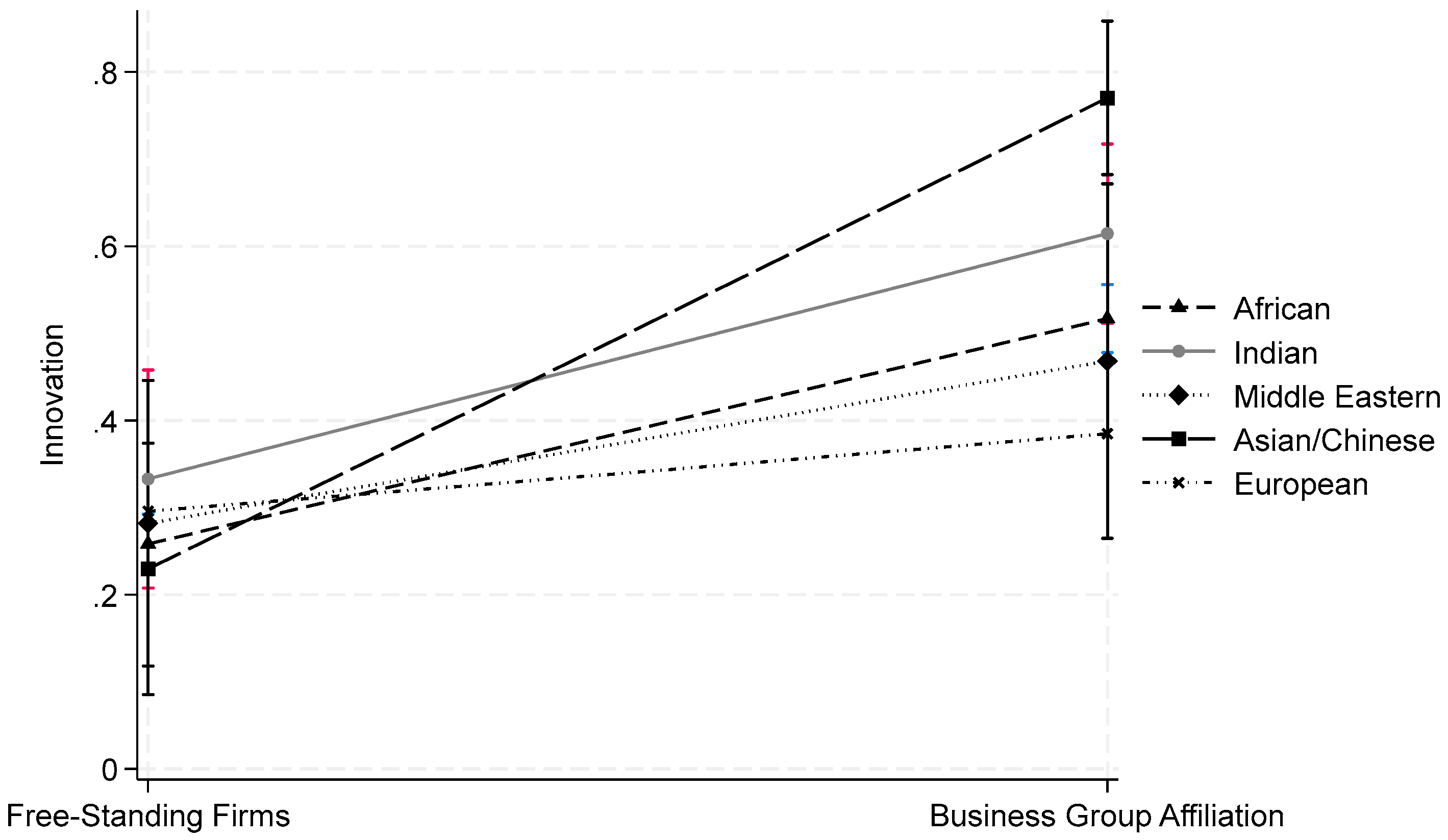

3.4. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Recommendations for Further Research and Policy Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Researchers associated with the Regional Programme for Enterprise Development (RPED) in sub-Saharan Africa, the forerunner to the WBES, recognized that indigenous Africans were also segmented along ethnic identity. However, researchers decided ‘to keep things simple and straightforward as possible we use very broad categories based on race alone’ (Fafchamps, 2004). Note that the categorization has three advantages: First, race is most of the time readily identifiable via physical features and name. Race information is, therefore straightforward to collect. Second, race is a relatively objective dimension of ethnicity. Third, ‘ethnic identity is often a matter of subjective assessment and…there is often tension around the issue of ethnic identification in Africa… It can be counter-productive to ask respondents to define their own ethnicity publicly” (Fafchamps, 2004, p. 360). Despite the empirical pragmatism of this categorization, the result has produced selection issues in research on minority entrepreneurs in Africa, an issue that we return to in our section on endogeneity and selection. The category ‘other’ primarily denotes individuals of mixed ancestry. We excluded this category since we cannot identify the owner’s minority identity. |

References

- Abascal, M., & Baldassarri, D. (2015). Love thy neighbor? Ethnoracial diversity and trust reexamined. American Journal of Sociology, 121, 722–782. [Google Scholar]

- Biggs, T., Raturi, M., & Srivastava, P. (2002). Ethnic networks and access to credit: Evidence from the manufacturing sector in Kenya. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 49, 473–486. [Google Scholar]

- Biggs, T., & Shah, M. K. (2006). African SMEs, networks, and manufacturing performance. Journal of Banking & Finance, 30, 3043–3066. [Google Scholar]

- Bonacich, E. (1973). A theory of middleman minorities. American Sociological Review, 1973, 583–594. [Google Scholar]

- Bräutigam, D. (2003). Close encounters: Chinese business networks as industrial catalysts in Sub-Saharan Africa. African Affairs, 102(408), 447–46. [Google Scholar]

- Bräutigam, D., & Tang, X. (2014). Going global in groups’: Structural transformation and China’s special economic zones overseas. World Development, 63, 78–91. [Google Scholar]

- Burt, R. S. (2000). The network structure of social capital. Research in Organizational Behavior, 22, 345–423. [Google Scholar]

- Carney, M., & Gedajlovic, E. (2002). The co-evolution of institutional environments and organizational strategies: The rise of family business groups in the ASEAN region. Organization Studies, 23(1), 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Carney, M., Gedajlovic, E. R., Heugens, P. P., Van Essen, M., & Van Oosterhout, J. H. (2011). Business group affiliation, performance, context, and strategy: A meta-analysis. Academy of Management Journal, 54, 437–460. [Google Scholar]

- Castellacci, F. (2015). Institutional voids or organizational resilience? Business groups, innovation, and market development in Latin America. World Development, 70, 43–58. [Google Scholar]

- Cerrato, D., & Piva, M. (2012). The internationalization of small and medium–sized enterprises: The effect of family management, human capital and foreign ownership. Journal of Management & Governance, 16, 617–644. [Google Scholar]

- Chand, M., & Ghorbani, M. (2011). National culture, networks and ethnic entrepreneurship: A comparison of the Indian and Chinese immigrants in the US. International Business Review, 20(6), 593–606. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, S. J., & Hong, J. (2000). Economic performance of group-affiliated companies in Korea: Intragroup resource sharing and internal business transactions. Academy of Management Journal, 43, 429–448. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, S. S. (1985). British–based investment groups before 1914. Economic History Review, 38, 230–251. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C. J., Lin, B. W., Lin, Y. H., & Hsiao, Y. C. (2016). Ownership structure, independent board members and innovation performance: A contingency perspective. Journal of Business Research, 69(9), 3371–3379. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen-Salem, A., Zanini, M. T. F., Walumbwa, F. O., Parente, R., Peat, D. M., & Perrmann-Graham, J. (2021). Communal solidarity in extreme environments: The role of servant leadership and social resources in building serving culture and service performance. Journal of Business Research, 135, 829–839. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, J., & Fafchamps, M. (2022). Labor conflict within foreign, domestic, and Chinese-owned manufacturing firms in Ethiopia. World Development, 159, 106037. [Google Scholar]

- Chua, A. L. (1998). Markets, democracy, and ethnicity: Toward a new paradigm for law and development. The Yale Law Journal, 108, 1–107. [Google Scholar]

- Cieślik, A., Michałek, J. J., & Michałek, A. (2022). Does firms and managerial experience matter for exporting? The case of selected EU member and non-member countries. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 19(5), 1238–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirera, X., & Muzi, S. (2020). Measuring innovation using firm-level surveys: Evidence from developing countries. Research Policy, 49(3), 103912. [Google Scholar]

- Commander, S., Estrin, S., & De Silva, T. (2024). Political connections, business groups and innovation in Asia. Comparative Economic Studies, 66(4), 639–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelissen, S. (2016). Japan’s official development assistance to sub-saharan africa: Patterns, dynamics, and lessons. In Japan’s development assistance: Foreign aid and the Post-2015 Agenda (pp. 149–165). Palgrave Macmillan UK. [Google Scholar]

- Crick, D., Kaganda, G. E., & Matlay, H. (2011). A study into the international competitiveness of low and high intensity Tanzanian exporting SMEs. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 18(3), 594–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, A. D., & Centeno-Caffarena, L. (2023). Migrant business families in central America. In M. Carney, & M. Dieleman (Eds.), De gruyter handbook of business families (pp. 519–540). Walter de Gruyter GmbH. [Google Scholar]

- Cuervo-Cazurra, A. (2016). Corruption in international business. Journal of World Business, 51, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, D., Johan, S., & Zhang, M. (2014). The economic impact of entrepreneurship: Comparing international datasets. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 22, 162–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daveri, F., & Parisi, M. L. (2015). Experience, innovation, and productivity: Empirical evidence from Italy’s slowdown. ILR Review, 68(4), 889–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K., Trebilock, M. J., & Heys, B. (2000). Ethnically homogeneous commercial elites in developing countries. Law & Policy the International Business, 32, 331–361. [Google Scholar]

- Dehejia, R. H., & Wahba, S. (2002). Propensity score-matching methods for nonexperimental causal studies. Review of Economics and statistics, 84(1), 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, P. (2009). Why do Chinese firms tend to acquire strategic assets in international expansion? Journal of World Business, 44, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dostie, B. (2018). The impact of training on innovation. ILR Review, 71(1), 64–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eduardsen, J., Marinova, S. T., González-Loureiro, M., & Vlačić, B. (2022). Business group affiliation and SMEs’ international sales intensity and diversification: A multi-country study. International Business Review, 31(5), 101989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, P. (1995). Embedded autonomy: States and industrial transformation. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fafchamps, M. (2000). Ethnicity and credit in African manufacturing. Journal of Development Economics, 61, 205–235. [Google Scholar]

- Fafchamps, M. (2004). Market institutions in sub-Saharan Africa: Theory and evidence (Comparative institutional analysis (CIA) series; 3. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, E., & Pilling, D. (2019). The other side of Chinese investment in Africa. Financial Times Online. Available online: https://www.ft.com/content/9f5736d8-14e1-11e9-a581-4ff78404524e (accessed on 2 March 2019).

- Fisman, R. (2001). Trade credit and productive efficiency in developing countries. World Development, 29, 311–321. [Google Scholar]

- Fisman, R. J. (2003). Ethnic ties and the provision of credit: Relationship–level evidence from African firms. Advances in Economic Analysis & Policy, 3, 10–24. [Google Scholar]

- Friar, J. H. (1995). Competitive advantage through product performance innovation in a competitive market. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 12(1), 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Fund for Peace Fragile States Index. (2015). Available online: https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/191749/fragilestatesindex-2015.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- George, G., Corbishley, C., Khayesi, J. N., Haas, M. R., & Tihanyi, L. (2016). Bringing Africa in: Promising directions for management research. Academy of Management Journal, 59, 377–393. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, A. (2010). Business groups in South Africa. In A. M. Colpan, T. Hikino, & J. R. Lincoln (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of business groups (pp. 547–574). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Granovetter, M. (1985). Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology, 91(3), 481–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, M. (2010). Business groups and social organization. In N. J. Smelser, & R. Swedburg (Eds.), The handbook of economic sociology (2nd ed., pp. 429–450). Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin-EL, E. W., & Olabisi, J. (2018). Breaking boundaries: Exploring the process of intersective market activity of immigrant entrepreneurship in the context of high economic inequality. Journal of Management Studies, 55, 457–485. [Google Scholar]

- Hearn, B., Oxelheim, L., & Randøy, T. (2018). The institutional determinants of private equity involvement in business groups—The case of Africa. Journal of World Business, 53(2), 118–133. [Google Scholar]

- Hearn, B., Oxelheim, L., & Randøy, T. (2023). The impact of indigenous culture and business group affiliation on corporate governance of African firms. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 32(3), 449–473. [Google Scholar]

- Hobday, M. (1995). East Asian latecomer firms: Learning the technology of electronics. World Development, 23, 1171–1193. [Google Scholar]

- Högberg, L., & Mitchell, C. (2023). Mixed embeddedness and entrepreneurship beyond new venture creation: Opportunity tensions in the case of reregulated public markets. International Small Business Journal, 41(2), 121–151. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, R. M., Jr., Hoskisson, R. E., Kim, H., Wan, W. P., & Holcomb, T. R. (2018). International strategy and business groups: A review and future research agenda. Journal of World Business, 53, 134–150. [Google Scholar]

- Hoskisson, R. E., Wright, M., Filatotchev, I., & Peng, M. W. (2013). Emerging multinationals from mid-range economies: The influence of institutions and factor markets. Journal of Management Studies, 50, 1295–1321. [Google Scholar]

- Isaac, B. L. (1974). European, lebanese, and African traders in pendembu, sierra leone: 1908–1968. Human Organization, 33, 111. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, V. D. (2017). Coloured South Africans: A middleman minority of another kind. Social Identities, 23(1), 4–28. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, G. (2000). Merchants to multinationals: British trading companies in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, G., & Wale, J. (1998). Merchants as business groups: British trading companies in Asia before 1945. Business History Review, 72, 367–408. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, P. T. (1988). African capitalism: The struggle for ascendency. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Khanna, T., & Palepu, K. G. (2010). Winning in emerging markets: A road map for strategy and execution. Harvard Business Press. [Google Scholar]

- Khanna, T., & Rivkin, J. W. (2006). Interorganizational ties and business group boundaries: Evidence from an emerging economy. Organization Science, 17(3), 333–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khayesi, J. N., George, G., & Antonakis, J. (2014). Kinship in entrepreneur networks: Performance effects of resource assembly in Africa. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38, 1323–1342. [Google Scholar]

- Kiggundu, M. N. (2002). Entrepreneurs and entrepreneurship in Africa: What is known and what needs to be done. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 7, 239–258. [Google Scholar]

- Koning, J. (2007). Chineseness and Chinese Indonesian business practices: A generational and discursive enquiry. East Asia, 24, 129–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Koning, J. (2013). Generational change in Chinese Indonesian SME’s. Catalysts of Change: Chinese Business in Asia, 2013, 231–250. [Google Scholar]

- Koning, J., & Verver, M. (2013). Historicizing the ‘ethnic’ in ethnic entrepreneurship: The case of the ethnic Chinese in Bangkok. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 25, 325–348. [Google Scholar]

- Kuncoro, W., & Suriani, W. O. (2018). Achieving sustainable competitive advantage through product innovation and market driving. Asia Pacific Management Review, 23(3), 186–192. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, H. J., Lee, S., & Ha, Y. E. (2021). Policy analysis of Korea’s development cooperation with sub-Saharan Africa: A focus on fragile states. International Development Planning Review, 43(4), 345–369. [Google Scholar]

- Landa, J. T. (1994). Trust, ethnicity, and identity: Beyond the new institutional economics of ethnic trading networks, contract law, and gift-exchange. University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K., & Park, C. (2017). The influence of trust and solidarity on knowledge sharing in business groups: A comparative study of South Korean chaebols. Asia Pacific Business Review, 23(5), 710–727. [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowski, P., Park, A., Hardy, W., Du, Y., & Wu, S. (2022). Technology, skills, and globalization: Explaining international differences in routine and nonroutine work using survey data. The World Bank Economic Review, 36(3), 687–708. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J., Van Assche, A., Li, L., & Qian, G. (2022). Foreign direct investment along the Belt and Road: A political economy perspective. Journal of International Business Studies, 53(5), 902–919. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, G. (2018, April 26). Ethnicity in Africa. Oxford research encyclopedia of African history. Available online: http://oxfordre.com/africanhistory/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.001.0001/acrefore-9780190277734-e-32 (accessed on 23 April 2022).

- Masulis, R. W., Pham, P. K., & Zein, J. (2011). Family business groups around the world: Financing advantages, control motivations, and organizational choices. Review of Financial Studies, 24, 3556–3600. [Google Scholar]

- McDade, B. E., & Spring, A. (2005). The ‘new generation of African entrepreneurs’: Networking to change the climate for business and private sector–led development. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 17, 17–42. [Google Scholar]

- Min, Y., Liao, Y. C., & Chen, Z. (2022). The side effect of business group membership: How do business group isomorphic pressures affect organizational innovation in affiliated firms? Journal of Business Research, 141, 380–392. [Google Scholar]

- Mitton, T. (2016). The wealth of subnations: Geography, institutions, and within-country development. Journal of Development Economics, 118, 88–111. [Google Scholar]

- Morrisey, O. (2012). FDI in sub-Saharan Africa: Few linkages, fewer spillovers. The European Journal of Development Research, 24, 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- Mubarik, M. S., Devadason, E. S., & Govindaraju, C. (2020). Human capital and export performance of small and medium enterprises in Pakistan. International Journal of Social Economics, 47(5), 643–662. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M. E. (1990). The competitive advantage of nations. Harvard Business Review, 68, 73–93. [Google Scholar]

- Portes, A., & Sensenbrenner, J. (1993). Embeddedness and immigration: Notes on the social determinants of economic action. American Journal of Sociology, 98, 1320–1350. [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran, V., & Shah, M. K. (1999). Minority entrepreneurs and firm performance in sub-Saharan Africa. The Journal of Development Studies, 36, 71–87. [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran, V., & Shah, M. K. (2007). Why are there so few black–owned firms in Africa? Preliminary results from enterprise survey data (Center for global development working paper, (104)). World Bank Group. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum, P. R., & Rubin, D. B. (1983). The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika, 70(1), 41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, J., Mendoza, X., & Choi, C. (2022). Do internationalizing business group affiliates perform better after promarket reforms? Evidence from Korean SMEs. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 39(2), 805–841. [Google Scholar]

- Siqueira, A. C. O., & Cosh, A. D. (2008). Effects of product innovation and organizational capabilities on competitive advantage: Evidence from UK small and medium manufacturing enterprises. International Journal of Innovation Management, 12(2), 113–137. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, I. Y. (2017). The next factory of the world: How Chinese investment is reshaping Africa. Harvard Business Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tajeddin, M., & Carney, M. (2017). SMEs export performance: African business groups. In Academy of management proceedings (Vol. 2017, No. 1, p. 10861). Academy of Management. [Google Scholar]

- Tajeddin, M., & Carney, M. (2019). African business groups: How does group affiliation improve SMEs’ export intensity? Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 43, 1194–1222. [Google Scholar]

- Tajeddin, M., & Carney, M. (2021). Business group competitive advantage & export performance: The case of Africa’s minority entrepreneur. In Academy of management proceedings (Vol. 2021, No. 1, p. 16047). Academy of Management. [Google Scholar]

- Verver, M., & Koning, J. (2024). An anthropological perspective on contextualizing entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 62(2), 649–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verver, M., Roessingh, C., & Passenier, D. (2020). Ethnic boundary dynamics in immigrant entrepreneurship: A Barthian perspective. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 32, 757–782. [Google Scholar]

- Waldinger, R. (1995). The ‘other side’ of embeddedness: A case-study of the interplay of economy and ethnicity. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 18(3), 555–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welter, F., Xheneti, M., & Smallbone, D. (2018). Entrepreneurial resourcefulness in unstable institutional contexts: The example of European Union borderlands. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 12, 23–53. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins, M. (1988). The freestanding company, 1870–1914: An important type of British foreign direct investment. Economic History Review, 1988, 259–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, O. E. (1985). Firms, markets, relational contracting. The Economic Institutions of Capitalism. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, G., & Cooke, F. L. (2023). Transient entrepreneurs?: Chinese migrant small commercial businesses in South Africa. Journal of International Management, 29(6), 101094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank Enterprise Survey. (2015). Enterprise survey indicator descriptions. WBES. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank Group. (2015). Doing business report. World Bank Group. [Google Scholar]

- Yenkey, C. B. (2015). Mobilizing a market: Ethnic segmentation and investor recruitment into the Nairobi Securities Exchange. Administrative Science Quarterly, 60, 561–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yenkey, C. B. (2018). The outsider’s advantage: Distrust as a deterrent to exploitation. American Journal of Sociology, 124(3), 613–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Wong, P. K., & Ho, Y. P. (2016). Ethnic enclave and entrepreneurial financing: Asian venture capitalists in Silicon Valley. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 10, 318–335. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, W., Raja, R., & Wen, G. (2023). Influence of “Primary Groups” on new Chinese immigrant entrepreneurship in Africa. International Migration Review, 2023, 01979183231190891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Definition | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DV. | Export Intensity | Sales exported directly as percentage of total sales. | WBES |

| Product Innovation | During the last three years, has this establishment introduced new or significantly improved products or services? | WBES | |

| INV. | Business Group Affiliation | Dummy indicating whether firms are part of larger enterprise. | Calculated from WBES |

| Mod. V. | Ethnicity | The ethnic identity of the current owner. | WBES |

| Control Variables | Firm size | Number of permanent workers: small = less than 50, medium = 50–100, large = more than 100 employees. | WBES |

| Firm Age | The number of years between the firm’s founding year and the year of its interview. | WBES | |

| Foreign Own. | Ownership of private foreign individuals, companies or organizations. | WBES | |

| Managerial Experience | How many years of experience working in this sector does the top manager have? | WBES | |

| Training | Formal training programs for permanent, FT employees ran in last fiscal. | WBES | |

| GDP/Export | Exports as a percentage of GDP. | The Global Competitiveness Report (GCR) | |

| DBR_ (DTF) | Doing Business distant to frontier score. | Ease of Doing Business (World Bank Group, 2015) | |

| Fragile Index | Fragile States Index: 0–120_higher more fragile. | Fund for Peace Fragile States Index (2015) | |

| Labor Regulation | Percent of firms choosing labor regulations as their biggest obstacle. | Calculated from WBES | |

| Political Instability | Percent of firms choosing political instability as their biggest obstacle. | Calculated from WBES |

| Variables | Obs. | Mean | Std. Dev. | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | (13) | (14) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Export | 1794 | 3.629 | 14.61 | 1.000 | |||||||||||||

| (2) Innovation | 1803 | 0.413 | 0.492 | 0.036 | 1.000 | ||||||||||||

| (3) BG | 1803 | 0.497 | 0.5 | −0.013 | 0.265 | 1.000 | |||||||||||

| (4) Ethnicity | 1803 | 2.101 | 1.622 | 0.073 | −0.168 | 0.033 | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| (5) Firm Age | 1803 | 19.53 | 16.91 | 0.094 | −0.052 | −0.162 | 0.139 | 1.000 | |||||||||

| (6) Firm Size | 1803 | 1.95 | 0.757 | 0.169 | −0.091 | −0.295 | 0.107 | 0.179 | 1.000 | ||||||||

| (7) Foreign Own | 1780 | 4.113 | 14.36 | 0.050 | −0.039 | −0.147 | 0.089 | 0.039 | 0.191 | 1.000 | |||||||

| (8) Mang. Exper. | 1757 | 15.60 | 10.17 | 0.083 | −0.059 | −0.197 | 0.110 | 0.330 | 0.152 | 0.059 | 1.000 | ||||||

| (9) Training | 1678 | 0.399 | 0.49 | 0.098 | −0.042 | −0.073 | 0.071 | 0.091 | 0.256 | 0.093 | 0.093 | 1.000 | |||||

| (10) GDP/Expo. | 1803 | 31.38 | 15.11 | 0.018 | 0.048 | −0.079 | 0.028 | 0.020 | −0.004 | 0.093 | 0.056 | 0.033 | 1.000 | ||||

| (11) DBR_DFT | 1803 | 54.30 | 10.46 | 0.070 | −0.223 | −0.068 | 0.367 | 0.145 | 0.083 | 0.021 | 0.158 | 0.170 | −0.026 | 1.000 | |||

| (12) Fragile | 1803 | 86.53 | 15.33 | −0.063 | 0.179 | 0.091 | −0.361 | −0.164 | −0.070 | −0.058 | −0.168 | −0.146 | −0.329 | −0.842 | 1.000 | ||

| (13) Labor Regulation | 1793 | 3.828 | 6.514 | 0.042 | 0.156 | −0.070 | −0.094 | 0.042 | 0.006 | 0.051 | 0.039 | −0.003 | 0.253 | −0.329 | 0.227 | 1.000 | |

| (14) Political Instability | 1793 | 4.026 | 4.016 | 0.024 | −0.240 | −0.117 | 0.189 | 0.083 | 0.124 | 0.156 | 0.115 | 0.166 | 0.300 | 0.610 | −0.765 | −0.279 | 1.000 |

| Hypothesis 1 | Hypotheses 2 and 3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Model 1 (OLS) Export | Model 2 (Probit) Innov. | Model 3 (OLS) Export | Model 4 (OLS) Export | Model 5 (Probit) Innov. | Model 6 (Probit) Innov. |

| Firm Age | 0.04 * | 0 | 0.038 | 0.036 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Firm Size | 2.309 *** | 0.037 | 2.246 *** | 2.27 *** | 0.025 | 0.038 |

| Foreign Own | −0.015 | 0.002 | −0.023 | −0.016 | 0.003 | 0.002 |

| Mang. Exper. | 0.045 | 0.001 | 0.042 | 0.047 | 0 | 0 |

| Training | 1.447 * | −0.064 | 1.426 * | 1.32 * | −0.026 | −0.046 |

| GDP/Expo. | 0.061 | 0.006 * | 0.071 * | 0.064 * | 0.006 * | 0.007 * |

| DBR_DFT | 0.176 * | 0.024 ** | 0.189 ** | 0.174 * | 0.026 | 0.026 *** |

| Fragile | 0.15 * | −0.002 | 0.192 ** | 0.150 * | 0.004 *** | 0.001 |

| Labor Regulation | 0.119 | −0.052 *** | 0.204 | 0.126 | −0.044 ** | −0.051 *** |

| Political Instability | −0.056 | 0.01 | −0.08 | −0.078 | 0.007 | 0.007 |

| BGA | 1.285 * | 0.927 *** | 1.238 * | 0.567 | 0.884 *** | 0.915 *** |

| African | - | - | - | - | ||

| Indian | 0.465 | −0.66 | 0.401 ** | 0.277 | ||

| Middle Eastern | 4.74 ** | 3.20 | −0.0170 | 0.090 | ||

| European | 1.82 * | 1.179 | −0.116 | 0.142 | ||

| Asian | 0.058 | −5.64 * | 0.678 *** | −0.115 | ||

| BG * African | - | - | ||||

| BG * Indian | 1.620 | 0.071 | ||||

| BG * Mid. Eastern | 3.075 | −0.259 | ||||

| BG * European | 0.790 | −0.597 ** | ||||

| BG * Asian | 7.56 ** | 1.10 *** | ||||

| Constant | −26.33 * | −2.507 * | −30.41 ** | −25.85 * | −3.198 ** | −2.948 ** |

| Industry control | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year control | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 1597 | 1584 | 1597 | 1597 | 1584 | 1584 |

| Adjusted/Pseudo R2 | 0.113 | 0.294 | 0.115 | 0.141 | 0.306 | 0.316 |

| F | 6.088 | 5.69 | 5.68 | |||

| Chi-square | 630.135 | - | 656.00 | 673.51 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tajeddin, M.; Carney, M. Analysis of Solidarity Mechanisms Affecting the Performance of Ethnic Minority Business Groups in Africa. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18040183

Tajeddin M, Carney M. Analysis of Solidarity Mechanisms Affecting the Performance of Ethnic Minority Business Groups in Africa. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(4):183. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18040183

Chicago/Turabian StyleTajeddin, Mahdi, and Michael Carney. 2025. "Analysis of Solidarity Mechanisms Affecting the Performance of Ethnic Minority Business Groups in Africa" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 4: 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18040183

APA StyleTajeddin, M., & Carney, M. (2025). Analysis of Solidarity Mechanisms Affecting the Performance of Ethnic Minority Business Groups in Africa. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(4), 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18040183