Abstract

Digitalisation has evolved as a multidimensional phenomenon and impacts the business world. SMEs heavily invest in digital platform capabilities to keep track of digital transformation, enabling them to perform business model experimentation to generate and develop innovation. This paper explores the role of these two crucial growth-promoting variables in the performance of art and craft-based firm’s performance. Through this paper, the researchers contest the argument that, although digital platform capabilities accelerate business model experimentation for firm performance, competitive advantage plays a significant mediating role. Along with these arguments, this study also explores the role of digital platform capability in business model experimentation. It examines the mediating role of business model experimentation in the forming of a competitive advantage. The research model under examination belongs to the explorative school of research; hence, the researchers have used partial least square–structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) on a sample of 211 Indian firms belonging to the category of art and craft-based businesses. The hypothesis testing results facilitate exciting insights about the direct and indirect effects of digital platform capabilities, business model experimentation, and competitive advantage on firm performance. In light of the research findings, policymakers, SME consultants, and managers may obtain practical insights in order to develop an intervention mechanism. Researchers working in this area will glean a fresh look at the antecedents of SME performance as this model is explorative; future research may explore the testing of the model in different geographic locations and industry contexts.

Keywords:

business model innovation; firm capability; PLS-SEM; craft-based ventures; India; emerging economy; entrepreneurial ventures; digital platform capabilities JEL Classification:

M13; O31; M150

1. Introduction

Digital transformation has become a cornerstone of sustainable competitive advantage in the contemporary business landscape, especially for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) navigating resource constraints and volatile market environments (Liao et al., 2024; N. Wang et al., 2023). This transformation is particularly significant for cultural heritage businesses, which traditionally rely on localised knowledge, artisanal practices, and physical engagement with heritage assets. Indian handicrafts symbolise the country’s rich cultural heritage and were a significant source of employment for the people during the colonial period. However, building a new India was incomplete without the contributions of small and medium-size enterprises (SMEs). For decades, tangible and intangible heritage have been inextricably linked to activities that generate subsistence for livelihood (Beall & Kanji, 1999; C. Grant, 2020). Indian art and crafts have been enriched because of India’s global strategic location and broad exposure to diverse civilisations (Guha-Thakurta, 2004; Sandhu, 2020). Regardless of their size and the nature of their operations, these firms have played a critical role in empowering the Indian economy (Venkatesh & Muthiah, 2012; Zhu et al., 2022) by providing the biggest source of employment after agriculture and contributing significantly to India’s gross industrial output and exports (Mukherjee & Mukherjee, 2022). Despite their importance, SMEs are profoundly unorganised, lack capital access, and have less technology exposure (Singh & Kaur, 2021). Moreover, SMEs in India have witnessed intensified competition due to the liberalisation, privatisation, and globalisation adopted as fundamental economic reforms in 1991, coupled with domestic reforms and the establishment of the WTO in 1995 (Paul, 2015). Though seen as game changers for the business landscape in India, these shifts laid the foundation for the transformation of indigenous enterprises (Chittoor et al., 2008). During the same decade (the 1990s), countries around the globe saw major disruptions in business models (Cassidy, 2003) because of the Internet boom. The disruption caused issues for economies but provided opportunities as well.

Responding to this competitive pressure, many SMEs use digital platforms to leverage their business strategies (Li et al., 2016). Scholars have therefore been working to apply emerging technologies such as digital platforms (Sarwar et al., 2024; N. Wang et al., 2023). Digital platforms have transformed traditional business models, enabling SMEs to leverage technology for enhanced operational efficiency and competitive advantage. The integration of digital platform capabilities—defined as the firm’s competencies to utilise digital infrastructures to create, deliver, and capture value—has emerged as a potent enabler of strategic renewal and operational agility in this sector (Cenamor et al., 2019; Falahat et al., 2020).

Cultural heritage SMEs may increase market reach, customer contact, and value delivery via digital platforms. These systems make heritage experiences dynamic and participatory through resource integration, co-creation, and data-driven decision-making (Liao et al., 2024). Many cultural heritage SMEs struggle with digital platforms despite these benefits. Strategic stagnation, low absorptive abilities, and a mismatch between digital operations and the firm’s identity often generate this conflict (Cenamor et al., 2019). Business model experimentation (BME) can fill these gaps and unleash digital platforms’ transformative potential. BME tests, adapts, and refines new value creation, delivery, and capture configurations (Bouwman et al., 2019). BME helps cultural heritage SMEs develop new business models, embrace hybrid solutions, and adjust to shifting consumer expectations using adaptive learning. BME enables cultural heritage SMEs to implement adaptive learning to develop new business models, hybrid solutions, and rapidly adjust to consumer expectations. Experimentation turns digital capabilities into strategic results.

This change leads to a competitive advantage—a distinctive position of the company which enables it to outperform its competitors. The competitive edge in digitalised markets is increasingly based on intangible assets such as innovation capacity, customer intimacy, and knowledge use, which are deeply linked to digital skills and experimental agility. Competitive advantage in cultural heritage may come from differentiated narratives, immersive digital experiences, or networked community participation facilitated by digital platforms and enhanced by BME. This study uses the resource-based view (RBV) and dynamic capabilities theory to argue that digital platform capabilities are scarce, valuable, and strategically reconfigurable assets that enable organisational flexibility and value creation (Liao et al., 2024). RBV stresses digital assets’ uniqueness, while dynamic capabilities theory emphasises organisational agility in reconfiguring them to adapt to changing market and technology landscapes.

Despite growing scholarly interest in digital transformation, few studies have systematically examined the mechanisms through which digital platform capabilities impact the performance of cultural heritage SMEs. In particular, the mediating roles of business model experimentation and competitive advantage remain underexplored. This study contributes to the growing body of literature on digital transformation by providing empirical evidence on the interplay between digital platform capabilities, business model experimentation, and competitive advantage in a niche yet critical domain.

2. Literature Review, Conceptual Model, and Hypotheses

The role of competitive advantage in a company’s success has been extensively discussed in the literature (Barney, 1991; R. M. Grant, 1991; Porter, 1985). A central concern remains how firms acquire and sustain this advantage over time (Barnett & McKendrick, 2004; Nayak et al., 2022; Newbert, 2008; C.-H. Wang & Juo, 2021). Traditional studies—particularly those rooted in the resource-based view (RBV)—have emphasised that resources which are valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable (VRIN) are central to achieving and maintaining a competitive edge (Barney, 1991; Newbert, 2008). However, recent scholarship has challenged the sufficiency of merely possessing such resources in today’s dynamic and volatile business environment. Even firms with similar resource endowments may exhibit divergent strategic behaviours and performance outcomes (Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000; C.-H. Wang, 2014). To address these limitations, the dynamic capabilities framework was introduced by (Teece et al., 1997) as an extension of the RBV, offering a more adaptive lens to explain how firms sustain competitiveness and drive superior long-term performance amid environmental turbulence (Helfat & Raubitschek, 2018; Sousa-Zomer et al., 2020). Technological advancement, digital transformation, and sustainability regulations have increased environmental uncertainty (N. Wang et al., 2023). In this evolving landscape, the ability to continuously reconfigure and optimise resource allocation has emerged as a critical source of competitive advantage (Tiberius et al., 2021).

Dynamic ability is the ability of an enterprise to identify opportunities and threats, seize new opportunities, and reorganise internal and external resources to respond effectively (Teece, 2007). Capacities are accumulated and are shaped by unique internal and external structures and interactions that are difficult to emulate (R. M. Grant, 1991; Soto-Acosta & Meroño-Cerdan, 2008, 2009). In other words, a capability may be a source of competitive advantage if it is durable, non-transparent, non-transferable and difficult to duplicate. Many studies have examined organisational capacity and performance without addressing competitiveness, while some have examined competitiveness as a proxy. (Weerawardena, 2003) found that marketing skill boosts competitive advantage in 324 manufacturing enterprises, emphasising its strategic importance.

Scholars have studied how dynamic capabilities—especially digital dynamic capabilities—impact organisations’ strategic behaviour and outcomes as digital technologies spread. Digital skills help organisations adapt to shifting market needs and technology advances, optimising resource allocation and seizing new possibilities (Teece, 2018). Adaptation is a sustainable competitive advantage in a fast-paced, digital world (Chen et al., 2024). This study examines SMEs’ competitive advantage capabilities, recognising that competitive advantage and performance are distinct but interrelated variables. The question is whether competitive advantage mediates the link between these competencies and business performance.

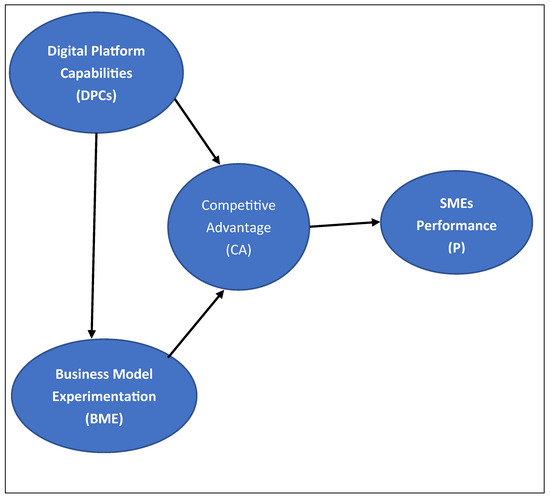

Digital platform capabilities and business model experimentation are studied as SME performance determinants via competitive advantages. The conceptual model needs these variables to add academic literature knowledge. Digital platform capabilities and business experimentation help SMEs obtain a competitive edge and perform better. A mediator in the conceptual model helps explain how underlying constructs affect SME performance. Thus, the below hypotheses were proposed. Figure 1 visually exhibit the conceptual model.

Figure 1.

The conceptual model of the determinants of SME performance.

2.1. The Impact of Digital Platform Capability on Business Model Experimentation

Digital platform capabilities (DPCs) are increasingly needed for SMEs to innovate and test their business strategies. Liao et al. (2024) state that powerful digital platform capabilities can increase enterprises’ openness to external interactions, enabling collaboration and resource sharing, which are essential for business model testing. The flexibility and standardisation of digital platforms enable SMEs to quickly access varied resources and insights to test business strategies. SMEs must adapt and innovate to meet market demands, and (Cenamor et al., 2019) found that digital platforms streamline business processes and improve decision-making. According to Kiyabo and Isaga (2020), integrating digital technologies into corporate operations encourages experimentation and creativity. Digital platforms facilitate business model experimentation and increase SMEs’ agility to respond quickly to changing market conditions. Falahat et al. (2020) found that business model experimentation helps organisations find and capitalise on market possibilities, increasing their competitive position. Resources for business model experimentation play a significant role in business model experimentation (Bouwman et al., 2019), and in this case, the critical resource is digital platform capability. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis.

H1:

The digital platform capability (DPC) of SMEs positively influences the firms’ business model experimentation (BME).

2.2. The Impact of Digital Platform Capability on Competitive Advantage

The theory of competitive advantage originates from competition theory, which posits that competitors and market dynamics are essential conditions (Bain, 1956). Competitive advantage reflects a firm’s superior performance, often achieved through cost leadership or product differentiation (Porter, 1985). The resource-based view (RBV) adds that such advantage stems from key firm-controlled resources and capabilities (Barney, 1991). However, in rapidly changing environments, these resources can depreciate or be imitated, limiting their sustainability (Mikalef & Pateli, 2017; Teece et al., 1997; G. Wang et al., 2015). Liao et al. (2024) claim that high-level digital platform enterprises can gain first-mover advantages over their competitors. Speed and agility are key in changing markets. Digital platforms enable SMEs to streamline operations and make strategic decisions, lowering costs and improving efficiency and competitiveness. Cenamor et al. (2019) found that digital platforms improve resource allocation and market response, which are crucial for competitiveness. Kiyabo and Isaga (2020) found that digital platform-using enterprises can differentiate themselves from competitors by creating unique value propositions. Today’s market, where customer expectations change, requires competitive distinctiveness. Falahat et al. (2020) also note that digital platforms enable SMEs to develop and adapt, which is crucial for competitive advantage. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis.

H2:

The digital platform capability (DPC) of SMEs positively influences the firms’ competitive advantage (CA).

2.3. The Impact of Business Model Experimentation on Competitive Advantage

Kiyabo and Isaga (2020) note that BME lets organisations test new business models to create distinct value propositions and differentiate them from the competition. This supports the resource-based perspective that unique competencies and resources sustain competitive advantages. Furthermore, Bouwman et al. (2019) found that BME-invested enterprises are more likely to discover and capitalise on emerging market possibilities, improving performance. BME’s iterative nature lets SMEs improve their strategy based on real-time feedback and market data, which is vital in today’s fast-paced business environment. As companies try out new business models, they enhance operational efficiency and produce customer-friendly solutions, strengthening their competitive position. Falahat et al. (2020) found that innovative business models can help organisations increase performance.

H3:

The business model experimentation (BME) of SMEs positively influences the firms’ competitive advantage (CA).

2.4. The Mediating Role of Business Model Experimentation

Digital platforms give SMEs the means and resources to engage in BME, giving them a competitive edge. DPC boosts a firm’s ability to innovate and adapt, while BME turns these capabilities into competitive advantages, according to Liao et al. (2024). BME mediates the dynamic capabilities framework’s recommendation that enterprises experiment and modify their business models to changing market conditions. Cenamor et al. (2019) add that the agility and reactivity of digital platforms enable enterprises to test different business strategies, improving market positioning. Bouwman et al. (2019) found that BME enterprises that use digital platforms fare better. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis.

H4:

Business model experimentation (BME) positively mediates the relationship between digital platform capabilities (DPCs) and competitive advantage (CA).

2.5. The Impact of Competitive Advantage on Overall Performance

According to Kiyabo and Isaga (2020), enterprises with a strong competitive edge can grow sales, profitability, and market share. The resource-based view holds that distinctive resources and competencies help a corporation outperform its competition. Falahat et al. (2020) found that competitive advantage drives international performance, which may be applied to overall performance measurements. A strong competitive advantage helps increase performance by differentiating products and services, reducing costs, and improving customer satisfaction. The literature also shows that organisations that use their competitive advantages to stay ahead are more likely to succeed. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis.

H5:

SMEs’ competitive advantage (CA) has a significantly positive impact on their overall performance.

2.6. The Mediating Role of Competitive Advantage

Research shows that BME promotes innovation and adaptation, but competitive advantage improves performance indicators. Kiyabo and Isaga (2020) note that BME enterprises are more likely to build distinctive capabilities that give them competitive advantages and boost performance. Falahat et al. (2020) found that competitive advantage helps BME improve performance. BME’s iterative nature lets organisations adjust their plans depending on market input, improving operational efficiency and consumer happiness. As organisations innovate their business models, they generate customer-friendly value propositions, strengthening their competitive position and boosting performance. On the other hand, Liao et al. (2024) claim that enterprises with excellent digital platform skills can leverage their competitive advantages to function well due to the agility and reactivity of digital platforms. Cenamor et al. (2019) show that DPC streamlines processes and informs strategic decisions, improving competitive posture. According to the resource-based concept, unique skills create sustainable competitive advantages that drive performance. Falahat et al. (2020) found that organisations that exploit their digital capabilities perform better. In the light of Rua et al. (2018) and Falahat et al. (2020), research senses a research gap to validate the mediating role of competitive advantage between the firm’s capabilities (digital platform capacities and business model experimentation) and performance. Hence, we propose the following hypothesis.

H6:

Competitive advantage (CA) positively mediates the relationship between business model experimentation (BME) and SME performance (P).

H7:

Competitive advantage (CA) positively mediates the relationship between digital platform capabilities (DPCs) and SME performance (P).

3. Research Methodology

This study aims to explore the relationship among diverse concepts belonging to a diverse theoretical background. Hence, the researchers adopted the second-generation multivariate statistical tool “structural equation modelling (SEM)” using SmartPLS (version 4).

Data collection and the sample: To test the proposed hypotheses, we conducted a survey targeting art and craft-based SMEs in India. Furthermore, our survey included only small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) that changed their business model because of the digitisation process in the last 24 months. Only respondents who answered the second question in the affirmative were included in our sample. The questionnaire was reviewed and tested by reading it out loud to executives and academics to improve the clarity of the questions. We collected the data in 2024. We conducted a survey at a trade fair organised in India’s National Capital Region (NCR). However, the respondents were contacted in person at the tradeshow. The benefit of contacting art and craft-based tradeshow exhibitors was that the research team obtained precise contact information on art and craft-based businesses from all parts of India. Detailed descriptive statistics are available in the annexture 1 (Refer Supplementary Material). The study sample consisted of 211 art and craft-based businesses. A detailed breakdown of business characteristics is presented in annexture 1. Regarding ownership structure, 57.8% of the businesses were operated as family-run enterprises. In comparison, the remaining 42.2% were part of Self-Help Groups (SHGs) or cooperative associations. This indicates a strong presence of both individual and collective models of business ownership in the sector. In terms of scale, measured by the number of artisans associated with each business, 44.6% of the businesses employed fewer than 10 artisans, while 37.0% had between 11 and 50 artisans, and 18.5% engaged more than 50 artisans. These figures suggest a dominance of small-scale operations, though a significant number of medium-sized and large artisan groups were also represented. The sample included a diverse range of product categories. The most prominent category was fashion jewellery, accounting for 18.9% of the sample, followed by festive decoration, gift items (14.2%), and lamp, light, and lawn accessories (13.3%). Other categories—such as house furniture (12.3%); candles, potpourri, and aromatics (11.8%); and carpets and rugs (9.5%)—also had considerable representation. A small portion of the businesses focused on bathroom accessories (7.1%), while 12.8% engaged in miscellaneous or less commonly found product types. As for the age of the business operations, the majority of the businesses (36.0%) had been active for 2 to 5 years, followed by 27.0% operating for 5 to 10 years, and 18.9% being relatively new with less than 2 years of experience. A further 18.0% of the sample represented long-established businesses operating for over 10 years, indicating a mix of emerging and experienced ventures in the craft-based sector. This descriptive overview highlights the heterogeneity of ownership patterns, scales, product diversification, and business maturity within the art and craft-based entrepreneurial ecosystem.

Measurement Scale: All variables examined under the model were measured based on the standard scales available in the existing literature: digital platform capability (Cenamor et al., 2019), firm performance and business model experimentation (Bouwman et al., 2019), and competitive advantage (Falahat et al., 2020). All variables were measured using a 7-point scale (1—Strongly Disagree to 7—Strongly Agree). A detailed list of measurement scales is available in Table 1.

Table 1.

Measurement Scale.

4. Results

The model in the research is exploratory, and to achieve the goal, the study adopts a partial least square for hypothesis testing (Hair et al., 2011) using SmartPLS. The researchers collected data from 211 handicraft-based business entities utilising a mix of online and offline surveys. As the study is exploratory in nature, the researchers identified PLS-based structural equation modelling as the best-suited second-generation multivariate statistical tool to test the proposed hypothesis. Adhering to all protocols related to PLS-SEM, the researchers confirmed content validity and reliability using two sets of data analysis PLS algorithm-based measurement model evaluation and structural model evaluation using a 5000-subsample bootstrapping procedure. However, the researchers acknowledge that the study is based on cross-sectional data, and testing whether the analysis is free from common-method bias is very much needed. The researchers followed the recommendation of Kock (2015) that suggests checking whether the VIF score (refer to Annex 1 for the Inner VIF Scores) is less than 5. After conducting this test, we found that the data are free from common-method bias. Further, the researchers checked the predictive relevance of the model and performed PLSpredict/CVPAT and found the Q square scores (refer to Annex 1) are more than 0, establishing the predictive relevance of the examined model.

4.1. Measurement Model Evaluation

For this study, the researchers first analysed the measurement model using the PLS algorithm results and found the measured model to be sufficient in order to proceed with further analysis. The key measurement model indicators are convergent validity, assessed using outer loading; average variance extracted (AVE); and internal consistency reliability using composite reliability and Cronbach’s alpha. The last test is related to discriminant validity using HTMT scores. All of the scores were measured well under the prescribed limits (refer to Table 2); after this measurement model evaluation, the researchers considered the model to be adequate for structural analysis.

Table 2.

Measurement Model Evaluation Statistics Score.

4.2. Structural Model Evaluation

For structural model assessment, the researchers followed the first four steps suggested by (Hair et al., 2011). These steps are as follows: Step 1—“Assessment of structural model for collinearity”; Step 2—“Assessment of significance and relevance of structural model relationship”; Step 3—“Assessment of the level of R2”; and Step 4—“Assessment of the f2 effect size”. Detailed structural model evaluation and hypothesis testing statistics scores are exhibited in Table 3. Based on the supporting measurement and structural analysis results, the researchers used the bootstrapping results to test the direct and indirect (mediating effect) hypothesis—see Table 3 for immediate hypothesis results and Table 4 for mediating effect testing. The bootstrapped results in Table 3 and Table 4 indicate that all the hypotheses have a p-value of 0.000, indicating that all of the proposed hypotheses were accepted.

Table 3.

Structural Model Evaluation and Direct Hypothesis Testing.

Table 4.

Mediating Effect Testing.

5. Discussion

The existing literature reports that adopting digital technologies and platforms has become a priority for several SMEs (Chen et al., 2024). However, there is a limited understanding of the implications of adopting digital technologies and platforms (Frishammar et al., 2018). Moreover, only adopting digital technologies is insufficient unless adequate digital technology capabilities are developed (Helfat & Raubitschek, 2018; Teece, 2018). This study fills this research gap by examining the relationship between digital platform capabilities, digital transformation, and SME performance. The results reveal that digital platform capability significantly positively impacts firm performance antecedents. These findings corroborate the findings of Cenamor et al. (2019) and re-emphasise the claim that digital platform capabilities must be aligned with orientations and firm-specific capabilities. Previous studies have focused on firm capabilities and firm performance (Cenamor et al., 2019; Helfat & Raubitschek, 2018; Teece, 2018) and posited the need to examine the potential mediating effects. To bridge this gap in the literature, this study also examined the impact of digital platform capabilities on business model experimentation and found a positive mediating role. This finding creates a scholarly debate and posits a contrasting result to Bouwman et al. (2019), in which the authors found a partial mediation relationship between resources for business model experimentation and firm performance. In this paper, we argue that the capabilities of digital platforms can be an antecedent for business model experimentation, which can lead to innovation pursuits and ultimately to improve the firm performance.

This paper theoretically contributes to a better understanding of the effect of digital platform capabilities on business model experimentation and their combined effect on the competitive advantage of the firm. The firm’s competitive advantage, ultimately leading to improved firm performance. This study implies that the capability of digital platforms also plays a significant role in business model innovation through rapid and lean experimentation. Here, it becomes essential to understand the mediating role of business model experimentation in digital platform capability. Business model experimentation plays a positive mediating role in digital platform capability. In previous studies by Bouwman et al. (2019), business model experimentation also positively influenced firm performance. This is one of the significant contributions of this study to the exploration of the factors underpinning business model experimentation and firm performance. However, it is essential to recall that digital platform capability positively leads to a competitive advantage. It is encouraging to report that competitive advantage leads to firm performance and significantly mediates the impact of digital platform capabilities and business model experimentation.

By integrating the existing literature and robust data analysis, this work provides a framework with which to address the new layer of complexity introduced by the digital transformation of cultural (art and crafts) heritage organisations. As a unit of analysis, the business model provides an insight into how businesses create, deliver, and capture value. These processes are affected by digital transformation, which involves a change in the architecture of processes, products, services, and information flows, taking into account the new role of the customer in engagement and satisfaction, the role of multiple players, and the integrated benefits.

The authors developed a framework for a digital business model using a well-known conceptualisation and based on selected digital business model constructs from an operational point of view. It has been found that business model experimentation and competitive advantage work together to mediate the relationship between digital platform capabilities and company performance, making it possible for these heritage arts and crafts to compete in a different way in the digital age.

Digital technologies enable numerous players to collaborate on integrating their data, information, and content creation skills, producing a competitive advantage. They form a new partnership engine based on resource integration rather than collaboration. Digital technologies’ pervasiveness, inherent dematerialization, and collaboration make this very promising. The concept applies to the enterprises’ new resource structure. By integrating different actors’ resources, resources become meta-informational and constantly replenished. Thus, the actors’ resource integration and data, information, and content development are crucial to enterprises’ competitive advantage.

However, the digital transformation of these arts and crafts organisations does not stop at digitising the offer; it must also facilitate the seamless transfer between and among channels, both online and offline, with a wider collective dimension. This is not just a channel change, but a vast network of interactions and touchpoints where the company and the consumer are not the only players. Numerous actors are involved in these processes and can influence the brainstorming process. Finally, the business model must be re-engineered with a new ecosystem and a collective perspective to ensure that all value network activities are informed. The multiplicity of actors to be considered may contribute to a competitive edge. Through economic and social capital, businesses can create and distribute value beyond the typical consumer. Technology facilitates mutual interaction, the basis for long-term improved corporate performance.

6. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Research Direction

The findings of this study are based on a unique sample (heritage art and craft-based SMEs) context that is considered to be traditional and has less interaction with modern technologies. The results indicate that a firm’s digital platform capabilities significantly influence its digital transformation and overall performance. However, this relationship is not linear, as prior researchers have highlighted the need to investigate the factors underpinning the relationship between digital platform capabilities and firm performance. In practice, digital platform capabilities impact a firm’s business model experimentation, temperament, and competitive advantage. This study has made a significant theoretical contribution by examining the mediating role of business model experimentation on a firm’s competitive advantage. This posits an inference of the managerial implication that to make a firm’s competitive advantage robust and agile, one needs to promote the practice of business model experimentation. To envision competing values, firms need to exercise business model experimentation; this is possible if the firm’s digital platform capabilities are robust. Investing resources in in-house digital platform development or prudently scouting the right vendor is essential to achieve the posited model’s outcomes. As the study concludes that a robust competitive advantage achieved by a firm leads to holistic performance, it is essential to note that the indirect effect of digital platform capabilities and enabling business model experimentations is also significant.

However, this study has rightly investigated the factors underpinning SMEs’ digital transformation-led performance; future researchers may extend the model by introducing other factors with moderating or mediating roles (firm, manager, and entrepreneur characteristics or micro-/macro-economic factors). The study’s major limitation is its sample design, as this was based on cross-sectional data, meaning the data captured represent the situation at one point in time. This limits the inference of causality among the variables. Future researchers may explore the possibilities of designing the same study using a longitudinal data collection mode and utilising multi-group analysis of the two time intervals. The current study investigated only the causality with structural equation modelling; in further research, one may explore the importance/performance role of individual variables and associated measurement items by utilising advanced PLS-SEM techniques like Importance–Performance Map Analysis.

Overall, this study provides a novel approach to examining the antecedents of firm performance in light of new technological interventions in order to make firms agile with strong digital platform capabilities and business model experimentation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jrfm18050265/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.A. (Kumar Aashish) and S.S.; methodology, K.A. (Kumar Aashish); software, K.A. (Kumar Aashish) and K.A. (Kumar Anubhav); validation, K.A. (Kumar Aashish), K.A. (Kumar Anubhav) and M.Z.; formal analysis, K.A. (Kumar Anubhav); investigation, K.A. (Kumar Aashish); resources, K.A. (Kumar Aashish); data curation, K.A. (Kumar Anubhav); writing—original draft preparation, K.A. (Kumar Aashish), K.A. (Kumar Anubhav), N.S. and S.S.; writing—review and editing, K.A. (Kumar Aashish), K.A. (Kumar Anubhav), N.S., S.S. and M.Z.; visualization, N.S.; supervision, K.A. (Kumar Aashish) and M.Z.; project administration, K.A. (Kumar Aashish) and M.Z.; funding acquisition, K.A. (Kumar Aashish) All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bain, J. S. (1956). Barriers to new competition: Their character and consequences in manufacturing industries. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, W. P., & McKendrick, D. G. (2004). Why are some organizations more competitive than others? Evidence from a changing global market. Administrative Science Quarterly, 49(4), 535–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beall, J., & Kanji, N. (1999). Households, livelihoods and urban poverty. International Development Department, University of Birmingham. [Google Scholar]

- Bouwman, H., Nikou, S., & de Reuver, M. (2019). Digitalization, business models, and SMEs: How do business model innovation practices improve performance of digitalizing SMEs? Telecommunications Policy, 43(9), 101828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, J. (2003). Dot.Con: How america lost its mind and money in the internet Era. HarperCollins Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Cenamor, J., Parida, V., & Wincent, J. (2019). How entrepreneurial SMEs compete through digital platforms: The roles of digital platform capability, network capability and ambidexterity. Journal of Business Research, 100, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Li, J., & Zhang, J. (2024). Digitalisation, data-driven dynamic capabilities and responsible innovation: An empirical study of SMEs in China. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 41(3), 1211–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chittoor, R., Ray, S., Aulakh, P. S., & Sarkar, M. B. (2008). Strategic responses to institutional changes: ‘Indigenous growth’ model of the Indian pharmaceutical industry. Journal of International Management, 14(3), 252–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K. M., & Martin, J. A. (2000). Dynamic capabilities: What are they? Strategic Management Journal, 21(10–11), 1105–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falahat, M., Ramayah, T., Soto-Acosta, P., & Lee, Y.-Y. (2020). SMEs internationalization: The role of product innovation, market intelligence, pricing and marketing communication capabilities as drivers of SMEs’ international performance. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 152, 119908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frishammar, J., Cenamor, J., Cavalli-Björkman, H., Hernell, E., & Carlsson, J. (2018). Digital strategies for two-sided markets: A case study of shopping malls. Decision Support Systems, 108, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, C. (2020). Roles of culture and cultural sustainability in eliminating poverty (pp. 1–11). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, R. M. (1991). The resource-based theory of competitive advantage: Implications for strategy formulation. California Management Review, 33(3), 114–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guha-Thakurta, T. (2004). Monuments, objects, histories: Institutions of art in colonial and post-colonial India. Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19(2), 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfat, C. E., & Raubitschek, R. S. (2018). Dynamic and integrative capabilities for profiting from innovation in digital platform-based ecosystems. Research Policy, 47(8), 1391–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiyabo, K., & Isaga, N. (2020). Entrepreneurial orientation, competitive advantage, and SMEs’ performance: Application of firm growth and personal wealth measures. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 9(1), 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. (2015). Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. International Journal of e-Collaboration, 11(4), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W., Liu, K., Belitski, M., Ghobadian, A., & O’Regan, N. (2016). E-leadership through strategic alignment: An empirical study of small- and medium-sized enterprises in the digital age. Journal of Information Technology, 31(2), 185–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z., Chen, J., Chen, X., & Song, M. (2024). Digital platform capability, environmental innovation quality, and firms’ competitive advantage: The moderating role of environmental uncertainty. International Journal of Production Economics, 268, 109124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikalef, P., & Pateli, A. (2017). Information technology-enabled dynamic capabilities and their indirect effect on competitive performance: Findings from PLS-SEM and fsQCA. Journal of Business Research, 70, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S., & Mukherjee, A. (2022). Indian SMEs in global value chains: Status, issues and way forward. Foreign Trade Review, 57(4), 473–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, B., Bhattacharyya, S. S., & Krishnamoorthy, B. (2022). Exploring the black box of competitive advantage—An integrated bibliometric and chronological literature review approach. Journal of Business Research, 139, 964–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newbert, S. L. (2008). Value, rareness, competitive advantage, and performance: A conceptual-level empirical investigation of the resource-based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 29(7), 745–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J. (2015). Market access and the mirage of marketing to the maximum: New measures. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 27(4), 676–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M. E. (1985). The competitive advantage: Creating and sustaining superior performance. Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rua, O., França, A., & Fernández Ortiz, R. (2018). Key drivers of SMEs export performance: The mediating effect of competitive advantage. Journal of Knowledge Management, 22(2), 257–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandhu, A. (2020). Fashioning wellbeing through craft: A case study of Aneeth Arora’s strategies for sustainable fashion and decolonizing design. Fashion Practice, 12(2), 172–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, Z., Gao, J., & Khan, A. (2024). Nexus of digital platforms, innovation capability, and strategic alignment to enhance innovation performance in the Asia Pacific region: A dynamic capability perspective. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 41(2), 867–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P., & Kaur, C. (2021). Factors determining financial constraint of SMEs: A study of unorganized manufacturing enterprises in India. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 33(3), 269–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Acosta, P., & Meroño-Cerdan, A. L. (2008). Analyzing e-business value creation from a resource-based perspective. International Journal of Information Management, 28(1), 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Acosta, P., & Meroño-Cerdan, A. L. (2009). Evaluating internet technologies business effectiveness. Telematics and Informatics, 26(2), 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa-Zomer, T. T., Neely, A., & Martinez, V. (2020). Digital transforming capability and performance: A microfoundational perspective. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 40(7/8), 1095–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D. J. (2007). Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strategic Management Journal, 28(13), 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D. J. (2018). Profiting from innovation in the digital economy: Enabling technologies, standards, and licensing models in the wireless world. Research Policy, 47(8), 1367–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., & Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 18(7), 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiberius, V., Stiller, L., & Dabić, M. (2021). Sustainability beyond economic prosperity: Social microfoundations of dynamic capabilities in family businesses. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 173, 121093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, S., & Muthiah, K. (2012). SMEs in India: Importance and contribution. Asian Journal of Management Research, 2(2), 792–796. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.-H. (2014). How relational capital mediates the effect of corporate reputation on competitive advantage: Evidence from Taiwan high-tech industry. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 82, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-H., & Juo, W. (2021). An environmental policy of green intellectual capital: Green innovation strategy for performance sustainability. Business Strategy and the Environment, 30(7), 3241–3254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G., Dou, W., Zhu, W., & Zhou, N. (2015). The effects of firm capabilities on external collaboration and performance: The moderating role of market turbulence. Journal of Business Research, 68(9), 1928–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N., Wan, J., Ma, Z., Zhou, Y., & Chen, J. (2023). How digital platform capabilities improve sustainable innovation performance of firms: The mediating role of open innovation. Journal of Business Research, 167, 114080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerawardena, J. (2003). The role of marketing capability in innovation-based competitive strategy. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 11(1), 15–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B., Nguyen, M., Sarm Siri, N., & Malik, A. (2022). Towards a transformative model of circular economy for SMEs. Journal of Business Research, 144, 545–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).