State Borrowing and Electricity Tariff in an Emerging Economy: Post-COVID-19 Experience

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Neo-Ricardian Theory

3. Electricity Tariff in Ghana

4. State Borrowing and Electricity Tariff

5. Methods

5.1. Model Estimation

5.2. Model Specification

5.2.1. Short-Term Model Specification

5.2.2. Long-Term Model Specification

5.3. Data

6. Results and Discussion

6.1. Unit Roots Test

6.2. Cointegration Test

6.3. Lag Length Selection Criterion

6.4. Short-Term and Long-Term Causal Relationships

6.5. Serial Correlation and Heteroskedasticity Tests

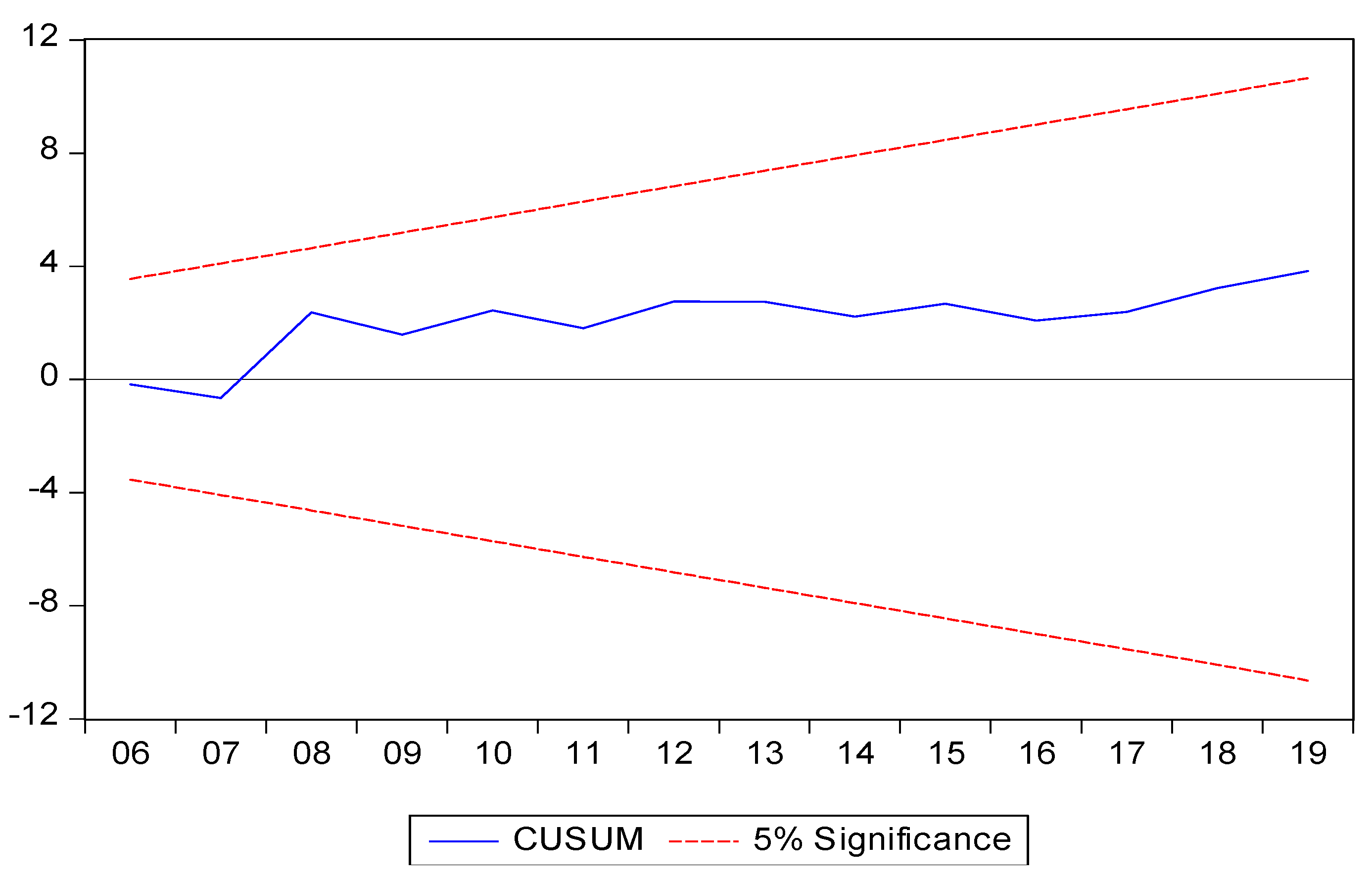

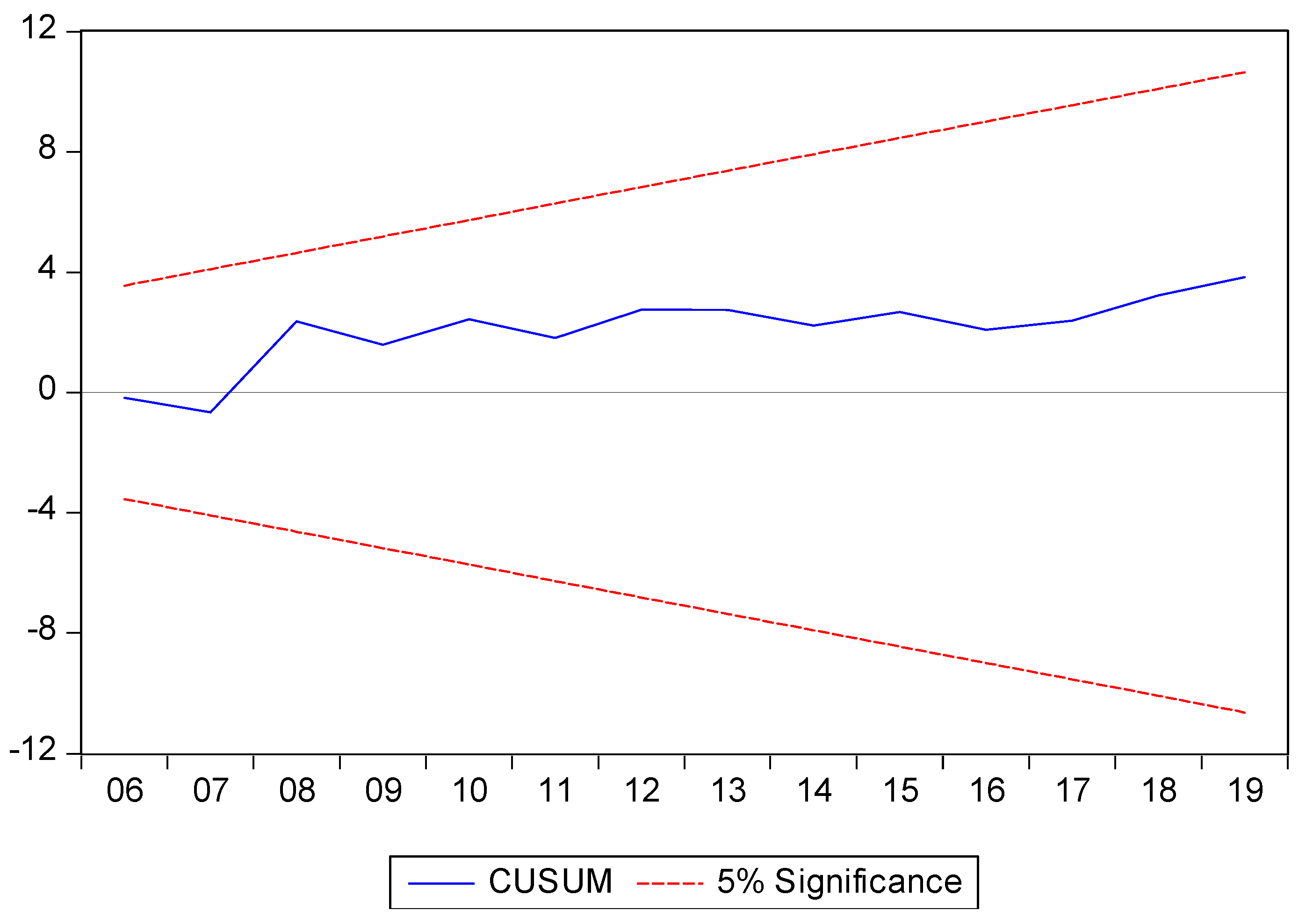

6.6. Residual and Stability Diagnostics Tests

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Acheampong, T., Menyeh, B. O., & Agbevivi, D. E. (2021). Ghana’s changing electricity supply mix and tariff pricing regime: Implications for the energy trilemma. Oil, Gas and Energy Law (OGEL), 19(3), 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Adom, P. (2016). The DDT effect: The case of economic growth, public debt and democracy relationship. Munich Personal RePEc Archive, (75022), 1–35. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/75022/ (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Afzal, M. (2012). Ricardian equivalence hypothesis: Evidence from Pakistan. Journal of Business Management and Economics, 3(6), 258–265. [Google Scholar]

- Anning, L., Ofori, C., & Affum, E. (2016). The impact of government on the economic growth of Ghana: A time-series analysis from 1990–2015. International Journal of Innovation and Economic Development, 2(5), 31–39. [Google Scholar]

- Bank of Ghana. (2021). January 2020 Bank of Ghana’s summary of financial and economic data: Monetary policy committee report. Bank of Ghana. [Google Scholar]

- Barro, R. J. (1979). On the determination of public debt. Journal of Political Economy, 87, 240–271. [Google Scholar]

- Barro, R. J. (1990). Government spending in a simple model of endogenous growth. Journal of Political Economics, 98(5/2), 103–125. [Google Scholar]

- Chirwa, T., & Odhiambo, N. (2020). Electricity consumption and economic growth: New evidence from advanced, emerging and developing economies. International Journal of Energy Sector Management, 14(1), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das-Gupta, A., & Mookherjee, D. (2017). Tax administration and tax evasion. Journal of Public Economics, 153, 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Dickey, D. A., & Fuller, W. A. (1981). Likelihood ratio statistics for autoregressive time series with unit root. Econometrica, 49, 1057–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donayre, L., & Taivan, A. (2017). Causality between public debt and real growth in the OECD: A country-by-country analysis. Economic Papers, 36(2), 156–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Energy Commission. (2020). 2020 energy (demand and supply) outlook for Ghana. Energy Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Garedow, F. A. (2022). Political institutions and economic performance in Ethiopia: An autoregressive distributed lag bound approach to co-integration. Journal of Economics and Development, 24(1), 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilton, S. K. (2021). Public debt and economic growth: Contemporary evidence from a developing economy. Asian Journal of Economics and Banking, 5(2), 173–193. [Google Scholar]

- IMF. (2019). Ghana: Staff report for the 2019 article IV consultation. IMF. [Google Scholar]

- IMF. (2021). International debt statistics database. IMF. [Google Scholar]

- Jalles, J. T. (2011). The impact of democracy and corruption on the debt-growth relationship in developing countries. Journal of Economic Development, 36(4), 41–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, K. (2015). Public debt overhang and economic growth, policy research institute, ministry of finance, Japan. Public Policy Review, 11(2), 247–276. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi, K., & Shirai, D. (2017). Debt-ridden borrowers and economic slowdown (CIGSWorking Paper 17-002E). The Canon Institute for Global Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Kourtellos, A., Stengos, T., & Tan, C. M. (2013). The effect of public debt on growth in multiple regimes. Journal of Macroeconomics, 38(8), 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, M., & Woo, J. (2010). Public debt and growth, IMF working paper 10/174. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1653188 (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Kumi, E. N. (2017). The electricity situation in Ghana: Challenges and opportunities, CGD policy paper. Center for Global Development. Available online: https://www.cgdev.org/publication/electricity-situation-ghana-challenges-and-opportunities (accessed on 2 July 2021).

- Ministry of Finance. (2020). 2020 budget statement and economic policy. Ministry of Finance. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Finance. (2023). 2023 budget statement and economic policy. Ministry of Finance. [Google Scholar]

- Onogbosele, D. O., & Ben, M. D. (2016). The impact of domestic debt on economic growth of Nigeria. Asian Research Journal of Arts & Social Sciences, 1(3), 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Owusu-Nantwi, V., & Erickson, C. (2016). Public debt and economic growth in Ghana. African Development Review, 28(1), 116–126. [Google Scholar]

- Panizza, U., & Presbitero, A. F. (2014). Public debt and economic growth: Is there a causal effect? Journal of Macroeconomics, 41, 21–41. [Google Scholar]

- Pasinetti, L. (1977). Lectures on the theory of production. Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Pesaran, M. H., Shin, Y., & Smith, R. (2001). Bound testing approaches to the analysis of level relationship. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 16(3), 289–326. [Google Scholar]

- Public Utilities Regulatory Commission. (2020). 2020 tariff report. Public Utilities Regulatory Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Reinhart, C. M., & Rogoff, K. S. (2010). Growth in a time of debt. NBER Working Paper No. 15639. National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Ricardo, D. (1951). On the principles of political economy and taxation. In P. Sraffa (Ed.), The works and correspondence of david ricardo 1. Cambridge University Press, with the collaboration of M. Dobb. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, J. (1962). Economic philosophy. C.A. Watts. [Google Scholar]

- Sraffa, P. (1960). Production of commodities by means of commodities. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. (2004). Ghana-enhanced heavily indebted poor countries (HIPC) debt initiative (English). World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. (2019). Ghana energy sector review. World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. (2020a). Ghana country assistance strategy. World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. (2020b). Ghana economic update: Enhancing growth through improved governance. World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. (2021). World Bank databank. World development indicators. Available online: http://www.data.worldbank.org (accessed on 2 July 2021).

| Intercept and No Trend | Intercept and Trend | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Levels | First Difference | Levels | First Difference |

| lntarifft | −1.287 | −3.378 ** | −1.564 | −3.289 * |

| lnsdt | −0.885 | −3.642 ** | −0.945 | −3.878 ** |

| lninft | −2.658 * | −4.152 *** | −3.393 * | −3.990 ** |

| lnexct | −1.571 | −3.475 ** | −2.610 | −3.554 ** |

| lnneteit | −1.390 | −3.071 ** | 2.638 | −3.778 *** |

| Dependent Variable | F-Statistic | Cointegration | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|

| lntarifft | 6.656257 | Yes | Estimate ECM (long-term model) |

| lnsdt | 1.396649 | No | Estimate ARDL (short-term model) |

| lninft | 2.143308 | No | Estimate ARDL (short-term model) |

| lnexct | 2.754151 | No | Estimate ARDL (short-term model) |

| lnneteit | 1.144439 | No | Estimate ARDL (short-term model) |

| Dependent Variable | Lag Length | Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) |

|---|---|---|

| lntarifft | 1 | 3.183147 * |

| lnsdt | 2 | −0.598639 * |

| lninft | 0 | 0.890928 * |

| lnexct, | 1 | −1.475172 * |

| lnneteit | 3 | 1.545634 * |

| Dependent Variable | Independent Variables Coefficients [p-Value] | ECTt−1 [p-Value] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lntarifft | lnsdt | lninft | lnexct | lnneteit | ||

| lntarifft | - | 3.279 [0.006] | −0.127 [0.831] | 0.904 [0.581] | 0.277 [0.517] | 1.057 [0.035] |

| lnsdt | 0.029 [0.617] | - | 0.311 [0.175] | −0.451 [0.335] | −0.049 [0.710] | - |

| lninft | 1.910 [0.482] | −4.031 [0.762] | - | −2.530 [0.646] | −7.861 [0.862] | - |

| lnexct | 0.013 [0.706] | 0.432 [0.031] | 0.049 [0.636] | - | 0.045 [0.541] | - |

| lnneteit | −0.115 [0.724] | −4.475 [0.428] | −0.511 [0.658] | −0.665 [0.772] | - | - |

| Dependent Variable | Serial Correlation LM F-Statistic [Prob. F] | Heteroskedasticity F-Statistic [Prob. F] |

|---|---|---|

| lntarifft | 0.403403 [0.5364] | 1.640081 [0.2056] |

| lnsdt | 1.259815 [0.3493] | 0.784561 [0.6473] |

| lninft | 0.122180 [0.7302] | 1.473456 [0.2599] |

| lnexct | 0.534272 [0.4778] | 0.657109 [0.6615] |

| lnneteit | 0.465617 [0.5025] | 0.294963 [0.9146] |

| * lntarifft | 0.002599 [0.9602] | 2.556428 [0.0736] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hilton, S.K.; Essuman, V.A.; Effisah, E.D.; Khalid, A.A. State Borrowing and Electricity Tariff in an Emerging Economy: Post-COVID-19 Experience. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18040184

Hilton SK, Essuman VA, Effisah ED, Khalid AA. State Borrowing and Electricity Tariff in an Emerging Economy: Post-COVID-19 Experience. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(4):184. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18040184

Chicago/Turabian StyleHilton, Sam Kris, Vida Aba Essuman, Ebenezer Dzinpa Effisah, and Andaratu Achuliwor Khalid. 2025. "State Borrowing and Electricity Tariff in an Emerging Economy: Post-COVID-19 Experience" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 4: 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18040184

APA StyleHilton, S. K., Essuman, V. A., Effisah, E. D., & Khalid, A. A. (2025). State Borrowing and Electricity Tariff in an Emerging Economy: Post-COVID-19 Experience. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(4), 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18040184