Effect of Financial Indicators on Corporate Social Responsibility: Evidence from Emerging Economies

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (1)

- Identify the direction and significance of the impact of profitability of firms from the developing and emerging economies on their overall level of CSR.

- (2)

- Identify the direction and significance of the impact of organizational slack of firms from the developing and emerging economies on their overall level of CSR.

- (3)

- Identify the direction and significance of the impact of leverage of firms from developing and emerging economies on their overall level of CSR.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Formulation

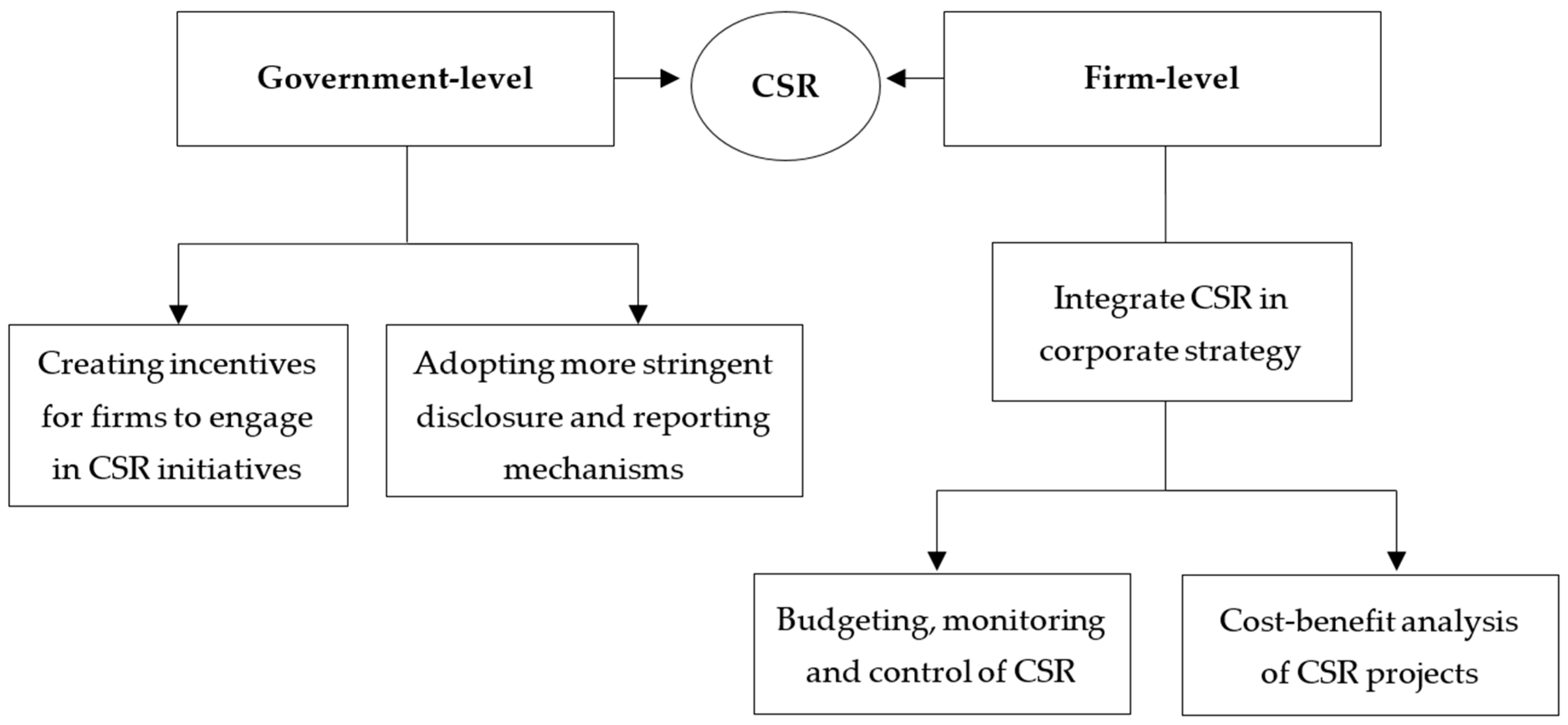

2.1. The Determinants of CSR

2.2. Prior Research on CSR and Financial Indicators

2.2.1. CSR and Firm’s Profitability

2.2.2. CSR and Financial Slack

2.2.3. CSR and Firm’s Financing

2.2.4. Explaining Inconsistent Results of Previous Literature

2.3. Hypothesis Formulation

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Data

3.2. Variable Specification

3.3. Methodology

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Results of Preliminary Tests

4.3. Regression Results

Profitability as a Motivator of CSR

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. List of Sample Countries

| Region | Country | Number of Obs. |

| Latin America | Argentina | 37 |

| Latin America | Brazil | 40 |

| Latin America | Chile | 35 |

| Asia | China | 29 |

| Latin America | Colombia | 10 |

| Africa | Egypt | 10 |

| Asia | India | 35 |

| Asia | Indonesia | 35 |

| Middle East | Israel | 25 |

| Middle East | Kuwait | 10 |

| Asia | Malaysia | 33 |

| Africa | Morocco | 5 |

| Asia | Philippines | 20 |

| East Europe | Poland | 35 |

| Middle East | Qatar | 20 |

| Middle East | Saudi Arabia | 15 |

| Asia | Singapore | 30 |

| Africa | South Africa | 30 |

| Asia | Thailand | 35 |

| Middle East | Turkey | 30 |

| Total | 519 |

Appendix B. Industry Sample

| Industry | Number of Obs. | % |

| Communication services | 75 | 14% |

| Consumer discretionary | 67 | 13% |

| Consumer staples | 40 | 8% |

| Energy | 90 | 17% |

| Healthcare | 5 | 1% |

| Industrials | 63 | 12% |

| Information technology | 6 | 1% |

| Materials | 68 | 13% |

| Utilities | 105 | 20% |

| Total | 519 | 100% |

References

- Abdul Rahman, R., & Alsayegh, M. F. (2021). Determinants of corporate environment, social and governance (ESG) reporting among Asian firms. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 14(4), 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aftab, J., Abid, N., Sarwar, H., Amin, A., Abedini, M., & Veneziani, M. (2024). Does corporate social responsibility drive financial performance? Exploring the significance of green innovation, green dynamic capabilities, and perceived environmental volatility. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 31(5), 1634–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H., Edwards, J. R., & Bradley, K. J. (2017). Improving our understanding of moderation and mediation in strategic management research. Organizational Research Methods, 20(4), 665–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaeed, K. (2006). The association between firm-specific characteristics and disclosure: The case of Saudi Arabia. Managerial Auditing Journal, 21(5), 476–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaeshi, K., Adi, B., Ogbechie, C., & Amao, O. (2006). Corporate social responsibility in Nigeria: Western mimicry or indigenous influences? The Journal of Corporate Citizenship, 24, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aras, G., & Crowther, D. (2009). Corporate sustainability reporting: A study in disingenuity? Journal of Business Ethics, 87, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, M., & Bond, S. (2020). Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Review of Economic Studies, 58, 277–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, M., Abeuova, D., & Alqatan, A. (2021). Corporate social responsibility and institutional investors: Evidence from emerging markets. Pakistan Journal of Commerce and Social Sciences, 15(1), 31–57. [Google Scholar]

- Bae, K. H., Kang, J. K., & Wang, J. (2011). Employee treatment and firm leverage: A test of the stakeholder theory of capital structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 100(1), 130–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Lahouel, B., Gaies, B., Ben Zaied, Y., & Jahmane, A. (2019). Accounting for endogeneity and the dynamics of corporate social–corporate financial relationship. Journal of Cleaner Production, 230(1), 352–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, A., & Makkar, B. (2019). CSR disclosure in developing and developed countries: A comparative study. Journal of Global Responsibility, 11(1), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulouta, I., & Pitelis, C. N. (2014). Who needs CSR? The impact of corporate social responsibility on national competitiveness. Journal of Business Ethics, 119(3), 349–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Box, G. E. P. (1979). Robustness in the strategy of scientific model building. In R. L. Launer, & G. N. Wilkinson (Eds.), Robustness in statistics (pp. 1–11). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brammer, S., Brooks, C., & Pavelin, S. (2006). Corporate social performance and stock returns: UK evidence from disaggregate measures. Financial Management, 35, 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S., & Pavelin, S. (2006). Voluntary environmental disclosures by large UK companies. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 33(7–8), 1168–1188. [Google Scholar]

- Buniamin, S. (2010). The Quantity and quality of environmental reporting in annual reports of public listed companies in Malaysia. Issues in Social and Environmental Accounting, 4(2), 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahan, S. F., De Villiers, C., Jeter, D. C., Naiker, V., & Van Staden, C. J. (2016). Are CSR disclosures value relevant? Cross-country evidence. European Accounting Review, 25(3), 579–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, D. J. (2000). Legitimacy theory or managerial reality construction? Corporate social disclosure in Marks and Spencer Plc corporate reports, 1969–1997. Accounting Forum, 24(1), 80–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, D., & Slack, R. (2006). Public visibility as a determinant of the rate of corporate charitable donations. Business Ethics: A European Review, 15(1), 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J. L. (2007). Why would corporations behave in socially responsible ways? An institutional theory of corporate social responsibility. Academy of Management Review, 32(3), 946–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chih, H.-L., Chih, H.-H., & Chen, T.-Y. (2010). On the determinants of corporate social responsibility: International evidence on the financial industry. Journal of Business Ethics, 93(1), 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, R., Jayantilal, S., & Ferreira, J. J. (2023). The impact of social responsibility on corporate financial performance: A systematic literature review. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 30(4), 1535–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormier, D., Magnan, M., & Van Velthoven, B. (2005). Environmental disclosure quality in large German companies: Economic incentives, public pressures or institutional conditions? European Accounting Review, 14(1), 3–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z., Liang, X., & Lu, X. (2015). Prize or price? Corporate social responsibility commitment and sales performance in the Chinese private sector. Management and Organization Review, 11(1), 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaliwal, D. S., Li, O. Z., Tsang, A., & Yang, Y. G. (2011). Voluntary nonfinancial disclosure and the cost of equity capital: The initiation of corporate social responsibility reporting. The Accounting Review, 86(1), 59–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaliwal, D. S., Radhakrishnan, S., Tsang, A., & Yang, Y. G. (2012). Nonfinancial disclosure and analyst forecast accuracy: International evidence on corporate social responsibility disclosure. The Accounting Review, 87(3), 723–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, W., Khurshid, A., Rauf, A., & Calin, A. C. (2022). Government subsidies influence on corporate social responsibility of private firms in a competitive environment. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 7(2), 16–28. [Google Scholar]

- Dyduch, J., & Krasodomska, J. (2017). Determinants of corporate social responsibility disclosure: An empirical study of Polish listed companies. Sustainability, 9(11), 1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ghoul, S., Guedhami, O., Kwok, C. Y., & Mishra, D. (2011). Does corporate social responsibility affect the cost of capital? Journal of Banking & Finance, 35(9), 2388–2406. [Google Scholar]

- Endrikat, J. (2016). Market reactions to corporate environmental performance related events: A meta-analytic consolidation of the empirical evidence. Journal of Business Ethics, 138, 535–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahad, P., & Nidheesh, K. B. (2021). Determinants of CSR disclosure: An evidence from India. Journal of Indian Business Research, 13(1), 110–133. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, S., Caroli, M. G., Cappa, F., & Chiappa, G. (2020). Are you good enough? CSR, quality management and corporate financial performance in the hospitality industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 88, 56–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R. E. (2010). Strategic management: A stakeholder theory. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Sanchez, I. M., Cuadrado-Ballesteros, B., & Frias-Aceituno, J. (2013). Determinants of government effectiveness. International Journal of Public Administration, 36(8), 567–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). (2016). GRI sustainability reporting standards. Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). [Google Scholar]

- Global Sustainable Investment Alliance (GSIA). (2022). Global sustainable investment review. GSIA. [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey, P. C. (2005). The relationship between corporate philanthropy and shareholder wealth: A risk management perspective. Academy of Management Review, 30(4), 777–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, P., & Hatch, N. (2007). Researching corporate social responsibility: An agenda for the 21st century. Journal of Business Ethics, 70(1), 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretz, R. T., & Malshe, A. (2019). Rejoinder to “Endogeneity bias in marketing research: Problem, causes and remedies. Industrial Marketing Management, 77, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulema, T. F., & Roba, Y. D. (2021). Internal and external determinants of corporate social responsibility practices in multinational enterprise subsidiaries in developing countries: Evidence from Ethiopia. Future Business Journal, 7(1), 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haniffa, R. M., & Cooke, T. E. (2005). The Impact of Culture and Governance on Corporate Social Reporting. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 24(5), 391–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heubeck, T., & Ahrens, A. (2024). Governing the responsible investment of slack resources in environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance: How beneficial are CSR committees? Journal of Business Ethics, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M., & Hammami, H. (2009). Voluntary disclosure in the annual reports of an emerging country: The case of Qatar. Advances in Accounting: Incorporating Advances in International Accounting, 25, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J., & Reber, B. H. (2011). Dimensions of disclosures: Corporate social responsibility (CSR) reporting by media companies. Public Relations Review, 37(2), 166–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-L., & Kung, F.-H. (2010). Drivers of environmental disclosure and stakeholder expectation: Evidence from Taiwan. Journal of Business Ethics, 96(3), 435–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D., Zanhour, M., & Keshishian, T. (2009). Peculiar strengths and relational attributes of SMEs in the context of CSR. Journal of Business Ethics, 87(3), 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, G. P., Kuo, C. Y., & Harberger, A. C. (2018). Cost-benefit analysis for investment decisions (1st ed.). Cambridge Resources International. [Google Scholar]

- Jo, H., & Harjoto, M. A. (2011). Corporate governance and firm value: The impact of corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 103(3), 351–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julian, S. D., & Ofori-Dankwa, J. C. (2013). Financial resource availability and corporate social responsibility expenditures in a sub-Saharan economy: The institutional difference hypothesis. Strategic Management Journal, 34(11), 1314–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kansal, M., Joshi, M., & Batra, G. S. (2014). Determinants of corporate social responsibility disclosures: Evidence from India. Advances in Accounting, 30(1), 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, A., Tiantubtim, E., Pussayapibul, N., & Davids, P. (2004). Implementing voluntary labour standards and codes of conduct in the Thai garment industry. Journal of Corporate Citizenship, 13, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A., Muttakin, M. B., & Siddiqui, J. (2013). Corporate governance and corporate social responsibility disclosures: Evidence from an emerging economy. Journal of Business Ethics, 114(2), 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, H. (2010). The effect of corporate governance elements on corporate social responsibility (CSR) reporting: Empirical evidence from private commercial banks of Bangladesh. International Journal of Law and Management, 52(2), 82–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KPMG. (2022). KPMG International survey of corporate responsibility reporting. KPMG International. [Google Scholar]

- Kuzey, C., & Uyar, A. (2017). Determinants of sustainability reporting and its impact on firm value: Evidence from the emerging market of Turkey. Journal of Cleaner Production, 143, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H., Li, Y., Xiao, Y., Xiong, X., & Zhang, W. (2025). Social responsibility and corporate borrowing. The European Journal of Finance, 31(2), 122–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund-Thomsen, P. (2004). Towards a critical framework on corporate social and environmental responsibility in the South: The case of Pakistan. Development, 47(3), 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, S., Chughtai, S., & Khawaja, K. F. (2020). An insight into determinants of corporate social responsibility decoupling: Evidence from pakistan. NICE Research Journal, 13(1), 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolis, J. D., & Walsh, J. P. (2003). Misery loves companies: Rethinking social initiatives by business. Administrative Science Quarterly, 48(2), 268–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matten, D., & Moon, J. (2008). “Implicit” and “explicit” CSR: A conceptual framework for a comparative understanding of corporate social responsibility. Academy of Management Review, 33(2), 404–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, A., Siegel, D., & Wright, P. (2006). Corporate social responsibility: Strategic implications. Journal of Management Studies, 43(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menassa, E., & Dagher, N. (2019). Determinants of corporate social responsibility disclosures of UAE national banks: A multi-perspective approach. Social Responsibility Journal, 16(5), 631–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nollet, J., Filis, G., & Mitrokostas, E. (2016). Corporate social responsibility and financial performance: A non-linear and disaggregated approach. Economic Modelling, 52, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orazayeva, A., & Arslan, M. (2022). Employee ownership, corporate social responsibility and financial performance: Evidence from the UK. International Journal of Managerial and Financial Accounting, 14(4), 362–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orazayeva, A., & Arslan, M. (2024). Social responsibility portfolio optimisation in the context of emerging markets. International Journal of Managerial and Financial Accounting, 16(3), 266–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlitzky, M., Schmidt, F. L., & Rynes, S. L. (2003). Corporate social and financial performance: A meta-analysis. Organizational Studies, 24, 403–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razali, M. W., Hii, W., Sin, S., Lunyai, J. A., Yau, J., Hwang, T., Yazreen, I., & Yusoff, M. D. (2018). Corporate social responsibility disclosure and firm performance of Malaysian public listed firms. International Business Research, 11(9), 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizk, R., Dixon, R., & Woodhead, A. (2008). Corporate social and environmental reporting: A survey of disclosure practices in Egypt. Social Responsibility Journal, 4(3), 306–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, R. W. (1992). Determinants of corporate social responsibility disclosure: An application of stakeholder theory. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 17, 595–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruf, B. M., Muralidhar, K., Brown, R. M., Janney, J. J., & Paul, K. (2001). An empirical investigation of the relationship between change in corporate social performance and financial performance: A stakeholder theory perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 32(2), 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, C. A., Russell, D. W., & Honea, H. (2016). Corporate social responsibility failures: How do consumers respond to corporate violations of implied social contracts? Journal of Business Ethics, 136, 759–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, M., Zulkifli, N., & Muhamad, R. (2010). Corporate social responsibility disclosure and its relation on institutional ownership: Evidence from public listed companies in Malaysia. Managerial Auditing Journal, 25(6), 591–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayekti, Y. (2017). The effect of slack resources on strategic corporate social responsibility (CSR): Empirical evidence on Indonesian listed companies. Global Journal of Business & Social Science Review, 5(2), 70–75. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, D., & Chakraborty, S. (2024). Corporate social responsibility and financial performance: Does CSR strategic integration matter? Cogent Business & Management, 11(1), 2392182. [Google Scholar]

- Sobhani, F. A., Amran, A., & Zainuddin, Y. (2009). Revisiting the practices of corporate social and environmental disclosure in Bangladesh. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 16(3), 167–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soobaroyen, T., Ramdhony, D., Rashid, A., & Gow, J. (2023). The evolution and determinants of corporate social responsibility (CSR) disclosure in a developing country: Extent and quality. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies, 13(2), 300–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starks, L. T. (2009). Corporate governance and corporate social responsibility: What do investors care about? What should investors care about? The Financial Review, 44(4), 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanovic, A., Milosevic, I., Arsic, S., Urosevic, S., & Mihaljovic, I. (2020). Corporate social responsibility as a determinant of employee loyalty and business performance. Journal of Competitiveness, 12(2), 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z., Xie, E., & Li, Y. (2009). Organizational slack and firm performance during institutional transitions. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 26, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB). (2018). SASB standards. Available online: www.sasb.org (accessed on 5 April 2022).

- Tagesson, T., Blank, V., Broberg, P., & Collin, S.-O. (2009). What explains the extent and content of social and environmental disclosures on corporate websites: A study of social and environmental reporting in Swedish listed corporations. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 16(6), 352–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M., & Wang, Y. (2022). Tax incentives and corporate social responsibility: The role of cash savings from accelerated depreciation policy. Economic Modelling, 116, 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullmann, A. A. (1985). Data in search of a theory: A critical examination of the relationships among social performance, social disclosure, and economic performance. Academy of Management Review, 10(2), 540–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Useem, M. (1988). Market and institutional factors in corporate contributions. California Management Review, 30(2), 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, W. (2008). Corporate social responsibility in developing countries. In A. Crane, A. McWilliams, D. Matten, J. Moon, & D. Siegel (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of corporate social responsibility (pp. 473–479). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Waddock, S., & Graves, S. (1997). The corporate social performance–financial performance link. Strategic Management Journal, 18, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q., Wu, C., & Sun, Y. (2015). Evaluating corporate social responsibility of airlines using entropy weight and grey relation analysis. Journal of Air Transport Management, 42, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2021). World Bank indicators 1996–2021. World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, F., Shao, Y., Fan, H., & Xie, Y. (2023). Analysis of the motivation behind corporate social responsibility based on the csQCA approach. Sustainability, 15(13), 10622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J. (2021). Reimagining corporate social responsibility in the era of COVID-19: Embedding resilience and promoting corporate social competence. Sustainability, 13(12), 6548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | Country | Determinants | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal | External | ||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Cormier et al. (2005) | Germany | Size (+), Industry (+), age of assets (+), risk (+), financial performance (0) | Public pressure (+), ownership (+) |

| Tagesson et al. (2009) | Swedish | Size (+), industry (+), financial performance (+) | Ownership (+) |

| Chih et al. (2010) | 34 countries | Size (+), financial performance (0) | Legal enforcement (+) |

| Hou and Reber (2011) | USA | Size (+), industry (+) | |

| Haniffa and Cooke (2005) | Malaysia | Size (+), industry (+), multiple listing, financial performance (+) | |

| Alsaeed (2006) | Saudi Arabia | Size (+), industry (0), financial performance (0), firm age (0) | |

| Rizk et al. (2008) | Egypt | Industry (+) | Ownership (+) |

| Sobhani et al. (2009) | Bangladesh | Industry (+) | |

| Buniamin (2010 | Malaysia | Size (+), Industry (+) | |

| Huang and Kung (2010) | Taiwan | Industry (+), leverage (−) | Govt (+), consumers (+), suppliers (−), employees (+), competitors (+), shareholding concentration (−) |

| H. Khan (2010) | Bangladesh | Size (+), financial performance (+) | |

| Saleh et al. (2010) | Malaysia | Size (+), financial performance (0) | Institutional ownership (+) |

| A. Khan et al. (2013) | Bangladesh | Managerial ownership (−), public ownership (+), foreign ownership (+) | |

| Kansal et al. (2014) | India | Size (+), industry (+) | |

| Bhatia and Makar (2019) | Russia | Industry (+) | International listing (+), board size (+), board independence (+) |

| Menassa and Dagher (2019) | UAE | Size (+), financial performance (+) | |

| Malik et al. (2020 | Pakistan | Size (+) | Ownership (0) |

| Fahad and Nidheesh (2021) | India | Firm age, financial leverage with different effects on CSR pillars, firm size (+) | Ownership with different effects on CSR pillars |

| Abdul Rahman and Alsayegh (2021) | 20 Asian countries | Firm size (+), financial performance (+), leverage (+) | |

| Soobaroyen et al. (2023) | Mauritius | cross-directorships (−) | |

| Variable Name | Measurement | Code |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Dependent variables | ||

| (1) CSR | Overall CSR score | CSR |

| Independent variables | ||

| (1) Financial indicators | ||

| (a) Profitability | ||

| Accounting-based performance | Return on Assets | ROA |

| Market-based performance | Tobin’s Q is measured as the sum of equity’s market value and debt’s book value by the total firm’s assets | TQ |

| (b) Organizational slack | Current Assets to Current Liabilities | CR |

| (c) Leverage | Debt as a percentage of Total assets | LEV |

| (2) Macro-level variables | ||

| (a) Government effectiveness | World Bank Government Indicators | GOVEFF |

| (b) Voice of stakeholders | World Bank Government Indicators | VOI |

| (3) Control variables: | ||

| Size | Natural logarithm of Total Assets | LnTA |

| GDP per capita | Natural logarithm of GDP per capita | LnGDP |

| Description | Panel A | Panel B | Panel C | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) CSR | (2) ENV | (3) SOC | (4) GOV | (5) ROA | (6) TQ | (7) CR | (8) LEV | (9) GOVEFF | (10) VOI | |

| Mean | 49.02 | 46.92 | 51.67 | 49.59 | 6.14 | 1.26 | 1.63 | 81.72 | 64.15 | 51.73 |

| Median | 54.15 | 54.15 | 62.50 | 54.15 | 5.36 | 0.99 | 1.23 | 64.05 | 65.38 | 51.72 |

| Maximum | 87.50 | 95.37 | 99.41 | 99.23 | 72.50 | 12.76 | 11.87 | 599.37 | 100.00 | 81.64 |

| Minimum | 4.17 | 1.00 | 3.81 | 0.08 | −81.51 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0 | 27.88 | 4.83 |

| Std. Dev. | 18.74 | 25.03 | 23.83 | 20.87 | 8.63 | 1.32 | 1.47 | 92.48 | 15.75 | 22.13 |

| Skewness | −0.48 | −0.12 | −0.37 | −0.10 | −1.12 | 3.96 | 4.07 | 2.10 | 0.21 | −0.41 |

| Kurtosis | 2.71 | 2.04 | 2.33 | 2.44 | 33.32 | 24.59 | 23.92 | 8.66 | 2.83 | 2.01 |

| Jarque-Bera | 21.81 ** | 21.38 ** | 21.47 ** | 7.66 ** | 19,991.69 ** | 11,440.53 ** | 10,893.38 ** | 1073.7 ** | 4.51 | 35.67 ** |

| Numb. of observations | 519 | 519 | 519 | 519 | 519 | 519 | 519 | 519 | 519 | 519 |

| Panel A | Panel B | Panel C | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GMM | 2SLS | OLS | |||||||||

| Variable | Coeff. | Std. Error | Prob. | Variable | Coeff. | Std. Error | Prob. | Variable | Coeff. | Std. Error | Prob. |

| CSR(−1) | 0.426 ** | 0.204 | 0.040 | C | 0.292 | 0.354 | 0.411 | C | 0.066 | 0.119 | 0.579 |

| ROA | 0.232 | 0.192 | 0.230 | ROA | 0.099 | 0.075 | 0.192 | ROA | 0.049 | 0.110 | 0.656 |

| GOVEFF | 0.004 | 0.009 | 0.634 | GOVEFF | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.259 | GOVEFF | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.889 |

| VOI | 0.014 | 0.012 | 0.248 | VOI | 0.005 | 0.004 | 0.238 | VOI | 0.002 ** | 0.001 | 0.014 |

| LnTA | 0.330 * | 0.172 | 0.057 | LnTA | 0.019 | 0.027 | 0.484 | LnTA | 0.041 *** | 0.010 | 0.000 |

| LnGDP | 0.003 | 0.007 | 0.651 | LnGDP | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.337 | LnGDP | 0.015 * | 0.009 | 0.095 |

| Effects Specification | Effects Specification | Effects Specification | |||||||||

| S.E. of regression | 0.138 | S.E. of regression | 0.083 | S.E. of regression | 0.173 | ||||||

| Sum squared resid. | 5.750 | Sum squared resid. | 2.099 | Sum squared resid. | 15.653 | ||||||

| J-statistic | 4.672 | Durbin-Watson stat. | 1.859 | Durbin-Watson stat. | 0.386 | ||||||

| Prob(J-statistic) | 0.457 | F-statistic | 14.847 *** | F-statistic | 23.432 *** | ||||||

| R-squared | 0.851 | R-squared | 0.183 | ||||||||

| Panel A | Panel B | Panel C | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GMM | 2SLS | OLS | |||||||||

| Variable | Coeff. | Std. Error | Prob. | Variable | Coeff. | Std. Error | Prob. | Variable | Coeff. | Std. Error | Prob. |

| CSR(−1) | 0.395 * | 0.201 | 0.052 | C | 0.257 | 0.284 | 0.366 | C | 0.051 | 0.121 | 0.673 |

| TQ | −0.022 | 0.103 | 0.831 | TQ | −0.001 | 0.008 | 0.881 | TQ | −0.002 | 0.008 | 0.854 |

| GOVEFF | 0.011 | 0.009 | 0.188 | GOVEFF | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.126 | GOVEFF | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.878 |

| VOI | 0.018 | 0.012 | 0.130 | VOI | 0.004 * | 0.003 | 0.092 | VOI | 0.002 ** | 0.001 | 0.013 |

| LnTA | 0.280 | 0.174 | 0.111 | LnTA | 0.023 | 0.022 | 0.300 | LnTA | 0.042 *** | 0.010 | 0.000 |

| LnGDP | 0.049 | 0.070 | 0.480 | LnGDP | 0.041 | 0.035 | 0.252 | LnGDP | 0.145 | 0.088 | 0.103 |

| Effects Specification | Effects Specification | Effects Specification | |||||||||

| S.E. of regression | 0.138 | S.E. of regression | 0.084 | S.E. of regression | 0.173 | ||||||

| Sum squared resid. | 5.692 | Sum squared resid. | 2.118 | Sum squared resid. | 15.664 | ||||||

| J-statistic | 5.806 | Durbin-Watson stat. | 1.848 | Durbin-Watson stat. | 0.378 | ||||||

| Prob(J-statistic) | 0.326 | F-statistic | 14.689 *** | F-statistic | 23.341 *** | ||||||

| R-squared | 0.849 | R-squared | 0.182 | ||||||||

| Panel A | Panel B | Panel C | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GMM | 2SLS | OLS | |||||||||

| Variable | Coeff. | Std. Error | Prob. | Variable | Coeff. | Std. Error | Prob. | Variable | Coeff. | Std. Error | Prob. |

| CSR(−1) | 0.414 | 0.228 | 0.072 | C | 0.247 | 0.279 | 0.377 | C | 0.104 | 0.056 | 0.063 |

| CR | −0.043 | 0.034 | 0.214 | CR | −0.000 | 0.009 | 1.000 | CR | −0.012 *** | 0.005 | 0.010 |

| GOVEFF | 0.009 | 0.009 | 0.284 | GOVEFF | −0.002 | 0.002 | 0.129 | GOVEFF | −0.000 | 0.001 | 0.828 |

| VOI | 0.016 | 0.012 | 0.183 | VOI | 0.004 * | 0.003 | 0.090 | VOI | 0.002 *** | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| LNTA | 0.303 * | 0.170 | 0.078 | LNTA | 0.023 | 0.022 | 0.282 | LNTA | 0.039 *** | 0.005 | 0.000 |

| LNGDP | 0.005 | 0.007 | 0.443 | LNGDP | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.249 | LNGDP | 0.014 *** | 0.005 | 0.004 |

| Effects Specification | Effects Specification | Effects Specification | |||||||||

| S.E. of regression | 0.139 | S.E. of regression | 0.084 | S.E. of regression | 0.172 | ||||||

| Sum squared resid. | 5.815 | Sum squared resid | 2.118 | Sum squared resid. | 15.466 | ||||||

| J-statistic | 6.300 | Durbin-Watson stat. | 1.847 | Durbin-Watson stat. | 0.380 | ||||||

| Prob(J-statistic) | 0.278 | F-statistic | 14.687 *** | F-statistic | 24.979 *** | ||||||

| R-squared | 0.849 | R-squared | 0.193 | ||||||||

| Panel A | Panel B | Panel C | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GMM | 2SLS | OLS | |||||||||

| Variable | Coeff. | Std. Error | Prob. | Variable | Coeff. | Std. Error | Prob. | Variable | Coeff. | Std. Error | Prob. |

| CSR(−1) | 0.468 | 0.255 | 0.070 | C | 0.060 | 0.118 | 0.614 | C | 0.077 | 0.118 | 0.516 |

| LEV | −0.001 | 0.001 | 0.244 | LEV | −0.000 | 0.000 | 0.215 | LEV | −0.000 | 0.000 | 0.265 |

| GOVEFF | 0.001 | 0.009 | 0.940 | GOVEFF | −0.001 | 0.001 | 0.285 | GOVEFF | −0.000 | 0.001 | 0.811 |

| VOI | 0.012 | 0.011 | 0.277 | VOI | 0.002 *** | 0.001 | 0.010 | VOI | 0.002 ** | 0.001 | 0.021 |

| LNTA | 0.243 ** | 0.122 | 0.049 | LNTA | 0.047 *** | 0.012 | 0.000 | LNTA | 0.042 *** | 0.010 | 0.000 |

| LNGDP | 0.004 | 0.006 | 0.497 | LNGDP | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.502 | LNGDP | −0.013 | 0.009 | 0.132 |

| Effects Specification | Effects Specification | Effects Specification | |||||||||

| S.E. of regression | 0.133 | S.E. of regression | 0.086 | S.E. of regression | 0.171 | ||||||

| Sum squared resid | 5.096 | Sum squared resid | 3.005 | Sum squared resid | 14.914 | ||||||

| J-statistic | 5.173 | Durbin-Watson stat | 1.300 | Durbin-Watson stat | 0.372 | ||||||

| Prob(J-statistic) | 0.395 | F-statistic | 7.489 *** | F-statistic | 22.494 *** | ||||||

| R-squared | 0.084 | R-squared | 0.180 | ||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Orazayeva, A.; Arslan, M. Effect of Financial Indicators on Corporate Social Responsibility: Evidence from Emerging Economies. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18030110

Orazayeva A, Arslan M. Effect of Financial Indicators on Corporate Social Responsibility: Evidence from Emerging Economies. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(3):110. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18030110

Chicago/Turabian StyleOrazayeva, Assem, and Muhammad Arslan. 2025. "Effect of Financial Indicators on Corporate Social Responsibility: Evidence from Emerging Economies" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 3: 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18030110

APA StyleOrazayeva, A., & Arslan, M. (2025). Effect of Financial Indicators on Corporate Social Responsibility: Evidence from Emerging Economies. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(3), 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18030110