Qualitatively Pre-Testing a Tailored Financial Literacy Measurement Instrument for Professional Athletes

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Orientation

1.2. Research Purpose and Objectives

1.3. The Need for Greater Financial Literacy and a Tailored Financial Literacy Measurement Instrument for Professional Athletes

1.4. Measurement of Financial Literacy

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Setting–Structured Interviews to Assess the Initial List of Questions

2.2. Research Participants and Sampling Method

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Reporting Style

3. Research Findings

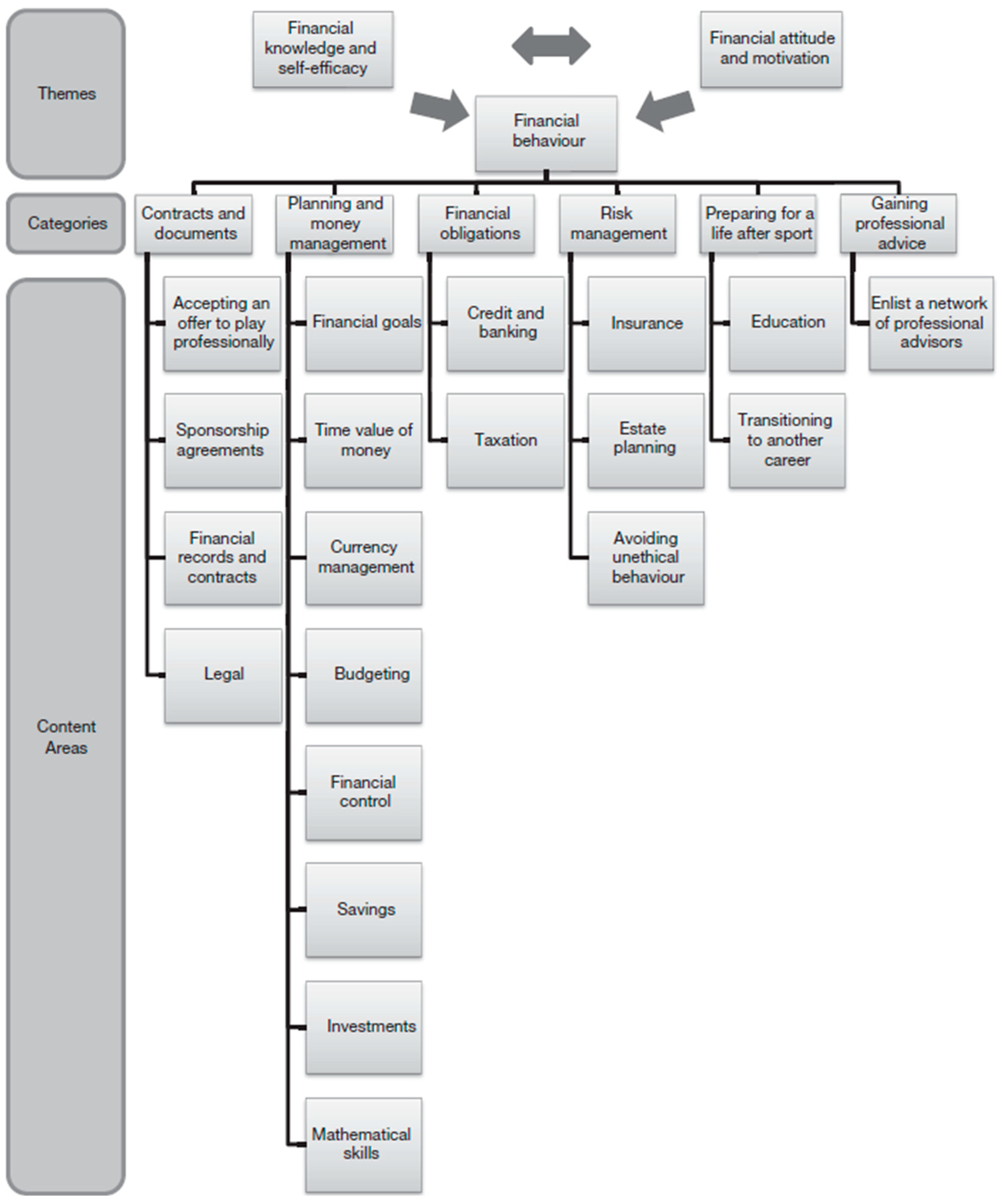

3.1. Questions Related to Category I: Contracts and Documents (Questions 1–5)

3.2. Questions Related to Category II: Planning and Money Management (Questions 6–18)

3.3. Questions Related to Category III: Financial Obligations (Questions 19–23)

3.4. Questions Related to Category IV: Risk Management (Questions 24–26)

3.5. Questions Related to Category V: Preparing for a Life After Sport (Questions 27–28)

3.6. Question Related to Category VI: Gaining Professional Advice (Question 29)

4. Discussion

4.1. Practical Implications

4.2. Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANT | Actor-network theory |

| IOSCO | International Organization of Securities Commissions |

| OECD | Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development |

Appendix A

| Question Number in the Interview Schedule | Proposed Question | Most Correct Answer to the Question | Content Area in the Framework Covered by the Question (See Figure 1) | Relevance of the Question for Inclusion in a Questionnaire to Assess Professional Athletes’ Financial Literacy | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not Relevant | Relevant | Very Relevant | ||||

| 1 | Which of the following is most important when accepting a player contract? | The opportunities I will get to develop as a player to showcase my talents and the quality of the coaches that could bring greater wealth in the long term. | Accepting an offer to play sport professionally. | 0 | 4 | 6 |

| 2 | Assume you have reached the pinnacle of the sport and you have played one (1) test match for South Africa. Which of the following is the best course of action when considering an offer to play overseas? Revised question: Why is it beneficial for a player who has played one Test match for their country to focus on gaining more international experience before pursuing a contract with an overseas club later in their career? | I am going to try to play more matches for South Africa and when I am approaching the end of my career as an international player, I will attempt to sign a more lucrative contract as a marquee player by an overseas club or franchise. Revised answer: It is more lucrative to be contracted as a marquee player by an overseas club or franchise. | Sponsorship agreements | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| 3 | Which of the following would you consider to be most relevant before signing a sponsorship agreement/contract? | All of the options are correct: I will make sure that I clearly understand the limitations imposed by the contract. I will make sure that I understand my rights and responsibilities in terms of the sponsorship agreement, including any performance requirements. I will consider getting advice from a legal expert to clearly understand the legal terminology and to make sure that the sponsorship agreement will not infringe on my player contract. | Financial records and contracts | 0 | 4 | 6 |

| 4 | Which of the following best describes your behaviour regarding financial records and contracts? (Swart, 2016) Revised question: How would you describe your approach to managing financial records and contracts? | I safeguard all important documents, including a recent balance sheet, a recent income statement, identity documents for all members of the household, insurance policy documentation, bank statements, contracts, and other relevant documents. Revised answer: I securely store all important documents, whether digitally or physically, including a recent balance sheet, income statement, identity documents for household members, insurance policies, bank statements, contracts, and other essential records. | Financial records and contracts | 1 | 6 | 3 |

| 5 | Which of the following statements best describes your behaviour when it comes to signing contracts? | There may be times when it is best to consult a qualified legal advisor before signing a contract. | Legal acumen | 0 | 2 | 8 |

| 6 | Which of the following is most important when setting financial goals? | Financial goals should be set to ensure financial sustainability beyond a person’s normal working age, and all short-, medium-, and long-term financial goals should be realistically achievable. | Financial goals | 0 | 4 | 6 |

| 7 | Imagine you have ZAR 1,000,000 cash in the bank. If you earn interest at 3.5% per year and the current inflation rate stays the same, how much will your money be worth in 10 years? (Louviere et al., 2016) | Less than today. | Time value of money | 10 | 5 | 4 |

| 8 | Assume the current exchange rate is as follows: Buy rate: USD 1 = ZAR 13.50 Sell rate USD 1 = ZAR 13.00 Assume you earned USD 100,000 after tax overseas and you want to convert that amount to South African rand to bank the money in your South African bank account. How much money will you bank? | ZAR 1,300,000 | Currency management | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| 9 | Do you have a monthly budget and regularly compare your monthly income and expenditure against the budgeted values? (Potrich et al., 2016) | Yes | Budgeting | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 10 | Which of the following best describes your financial behaviour? | I consider the opportunity cost of a purchase and know that money spent on one item cannot be spent on another. | Financial control | 0 | 6 | 4 |

| 11 | Which of the following best describes your view about saving? | I think professional athletes need to save a significant portion of their income from a young age. | Savings | 0 | 3 | 7 |

| 12 | Assume you have ZAR 100,000 in the bank. This money earns interest at 10% per year and the interest is reinvested. If you ignore any tax implications, how much money will you have in two (2) years? (Lusardi & Mitchell, 2014) | ZAR 121,000 | Savings | 1 | 4 | 5 |

| 13 | Which one of the following investment options usually provides the highest rate of return in the long term (i.e., longer than 20 years)? (Lusardi & Mitchell, 2014; Finke et al., 2017) | A well-managed diversified share portfolio | Investments | 1 | 6 | 3 |

| 14 | Do you think that a proposed investment with a high return is likely to also be a high-risk investment? (OECD, 2018) | Yes | Investments | 0 | 4 | 6 |

| 15 | If you invest ZAR 100,000 in a unit trust that only invests in offshore shares, is there any chance that your investment will be worth less than ZAR 100,000 one year later? | Yes | Investments | 1 | 6 | 3 |

| 16 | Which one of the following statements do you think is the best advice for a young professional athlete regarding investments? | Professional athletes need to have the acumen (or skill) to evaluate an appropriate investment so that they can manage a diversified investment portfolio with the assistance of a certified financial planner (CFP®). | Investments | 1 | 5 | 4 |

| 17 | Assume a new sports field is laid out. On day one, a patch of grass is planted in the middle of the sports field. If the patch of grass doubles in size every day, it will take 24 days for the entire field to be covered in grass. How long will it take for half of the sports field to be covered in grass? (Louviere et al., 2016) | 23 days | Mathematical skills | 5 | 5 | 0 |

| 18 | Which one of the following represents the biggest risk of getting injured? (Louviere et al., 2016) | 1 in 10 chances | Mathematical skills | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| 19 | Which of the following do you think is most likely to be a “high-cost” finance option? | Bank overdraft | Credit and banking | 0 | 4 | 6 |

| 20 | When you buy a property with a 10-year bond, the monthly instalments will be more than if you get a 20-year bond, but the total interest repaid over the term of the loan will be less in the case of the 10-year bond. Do you think the preceding statement is correct? (Louviere et al., 2016) Revised question: Does a 10-year home loan have higher monthly instalments, but lower overall interest than a 20-year home loan? (Louviere et al., 2016) | Yes | Credit and banking | 0 | 3 | 7 |

| 21 | Which one of the following investment options does not provide for a tax incentive? | Investments in shares | Taxation | 0 | 7 | 3 |

| 22 | Which one of the following statements about income tax is most correct? | Professional athletes need to have basic tax knowledge so that they can recognise when they need to consult a qualified tax or accounting expert, especially when they are earning income abroad. | Taxation | 0 | 2 | 8 |

| 23 | The way South Africans are taxed on income earned outside South Africa has changed. Which of the following best describes how the Act will be applied in the future? | The first ZAR 1 million of an individual’s private-sector foreign employment income is not subject to income tax in South Africa as long as the individual spent more than 183 full days outside South Africa in the preceding 12-month period (of which at least 60 days were for a continuous period). | Taxation | 0 | 3 | 7 |

| 24 | Which one of the following statements about insurance is most correct? | Professional athletes need to have the skill or ability to select a reputable independent broker to assist with their insurance needs (if necessary). | Insurance | 0 | 4 | 6 |

| 25 | Do you have a will and do you have enough capital assets or reserves to pay off your outstanding debt and cover your dependants’ living expenses when you pass away? (Swart, 2016) | Yes | Estate planning | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 26 | Which one of the following statements about unethical behaviour do you agree with the most? | People with a high level of financial literacy and sound financial planning are more likely to avoid unethical behaviour (match fixing, doping, social drugs, etc.). | Avoid unethical behaviour | 0 | 4 | 6 |

| 27 | Which one of the following statements best describes your view about gaining a qualification? | I have consulted a career development planner or sports psychologist to identify a career option when my sporting career ends, and I am currently studying towards (or have completed) a tertiary qualification or artisan skill to develop a scarce skill. | Education | 0 | 2 | 8 |

| 28 | Which one of the following statements best describes you? Revised question: Which one of the following statements about transitioning to another career is most correct? | I have been doing “shadow work” from a young age and I am progressing well to gain a qualification for a future career path when my sporting career ends. | Transitioning to another career | 0 | 4 | 6 |

| 29 | Which one of the following statements best describes you when it comes to consulting with expert advisors? Revised question: Which one of the following statements about obtaining professional financial advice is most correct? | I consult a range of qualified advisors (such as a financial planner or a tax specialist, when necessary) for financial advice and I always check their credentials and gain some background information on them before I consult them. | Enlist a network of professional advisors | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| It was proposed that question 17 be excluded from the final questionnaire. | ||||||

References

- Alshenqeeti, H. (2014). Interviewing as a data collection method: A critical review. English Linguistics Research, 3(1), 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balliauw, M., & Van Den Spiegel, T. (2018). Managing professional footballers’ finances to avoid financial problems: A Belgian survey. Sport, Business and Management: An International Journal, 8(4), 318–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist, 37, 122–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornman, M., & Ramutumbu, P. (2019). A conceptual framework of tax knowledge. Meditari Accountancy Research, 27(6), 823–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandner, J., & Omondi-Ochieng, P. (2022). Bankruptcy-Based divorces in the national football league and the national basketball association: Causes, cases, and cures. Journal of Multidisciplinary Research, 14(1), 71–86. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 13(2), 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C. J., Webb, T. L., Robinson, M. A., & Cotgreave, R. (2019). Athletes’ retirement from elite sport: A qualitative study of parents and partners’ experiences. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 40, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buschle, C., Reiter, H., & Bethmann, A. (2022). The qualitative pretest interview for questionnaire development: Outline of programme and practice. Quality & Quantity, 56(2), 823–842. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, K., Kim, J., Lusardi, A., & Camerer, C. F. (2015). Bankruptcy rates among NFL players with short-lived income spikes. American Economic Review, 105(5), 381–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, D. (2003). Pretesting survey instruments: An overview of cognitive methods. Quality of Life Research, 12, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Beckker, K., De Witte, K., & Van Campenhout, G. (2019). Identifying financially illiterate groups: An international comparison. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 43(5), 490–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmel, N. (2013). Sampling and choosing cases in qualitative research: A realist approach. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Englander, M. (2019). General knowledge claims in qualitative research. The Humanistic Psychologist, 47(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finke, M. S., Howe, J. S., & Huston, S. J. (2017). Old age and the decline in financial literacy. Management Science, 63(1), 213–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flick, U. (Ed.). (2018). The SAGE handbook of qualitative data analysis. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Gerrans, P., & Hershey, D. A. (2017). Financial adviser anxiety, financial literacy, and financial advice seeking. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 51(1), 54–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, K., & Kumar, S. (2020). Financial literacy: A systematic review and bibliometric analysis. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 45(1), 80–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, A., & Singh, S. (2024). Financial self-efficacy of consumers: A review and research agenda. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 48(2), e13024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happ, R., Förster, M., Rüspeler, A. K., & Rothweiler, J. (2018). Young adults’ knowledge and understanding of personal finance in Germany: Interviews with experts and test-takers. Citizenship, Social and Economics Education, 17(1), 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H. J., & Fraser, I. (2021). My sport won’t pay the bills forever: High-performance athletes’ need for financial literacy and self-management. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 14(7), 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huston, S. J. (2010). Measuring financial literacy. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 44(2), 296–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IOSCO & OECD. (2019). Core competencies framework on financial literacy for investors. Available online: https://www.iosco.org/library/pubdocs/pdf/IOSCOPD639.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Kaiser, T., & Menkhoff, L. (2017). Does financial education impact financial literacy and financial behavior, and if so, when? The World Bank Economic Review, 31(3), 611–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knights, S., Sherry, E., & Ruddock-Hudson, M. (2016). Investigating elite end-of-athletic-career transition: A systematic review. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 28(3), 291–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoll, M. A., & Houts, C. R. (2012). The financial knowledge scale: An application of item response theory to the assessment of financial literacy. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 46(3), 381–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhle, J. (2016). Comment: “If you can’t measure it, you can’t improve it” (Lord Kelvin). Neurology, 87(13), 1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeBaron, A. B., & Kelley, H. H. (2021). Financial socialization: A decade in review. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 42(1), 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louviere, J., Bateman, H., Thorp, S., & Eckert, C. (2016). Developing new financial literacy measures to better link financial capability to outcomes (pp. 3–58). Financial Literacy Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Lown, J. M. (2011). Development and validation of a financial self-efficacy scale. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 22(2), 54–63. [Google Scholar]

- Lusardi, A., & Messy, F. A. (2023). The importance of financial literacy and its impact on financial wellbeing. Journal of Financial Literacy and Wellbeing, 1(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2014). The economic importance of financial literacy: Theory and evidence. Journal of Economic Literature, 52(1), 5–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGraw, S., Deubert, C., Lynch, H. F., Nozzolillo, A., & Cohen, I. G. (2019). NFL or ‘Not For Long’? Transitioning out of the NFL. Journal of Sport Behavior, 42(4), 461–492. [Google Scholar]

- McGreary, M., Eubank, M., Morris, R., & Whitehead, A. (2020). Thinking aloud: Stress and coping in junior cricket batsmen during challenge and threat states. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 127(6), 1095–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mindra, R., Moya, M., Zuze, L. T., & Kodongo, O. (2017). Financial self-efficacy: A determinant of financial inclusion. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 35(3), 338–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monette, D. R., Sullivan, T. J., & DeJong, C. R. (2011). Applied social research: A tool for the human services. Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

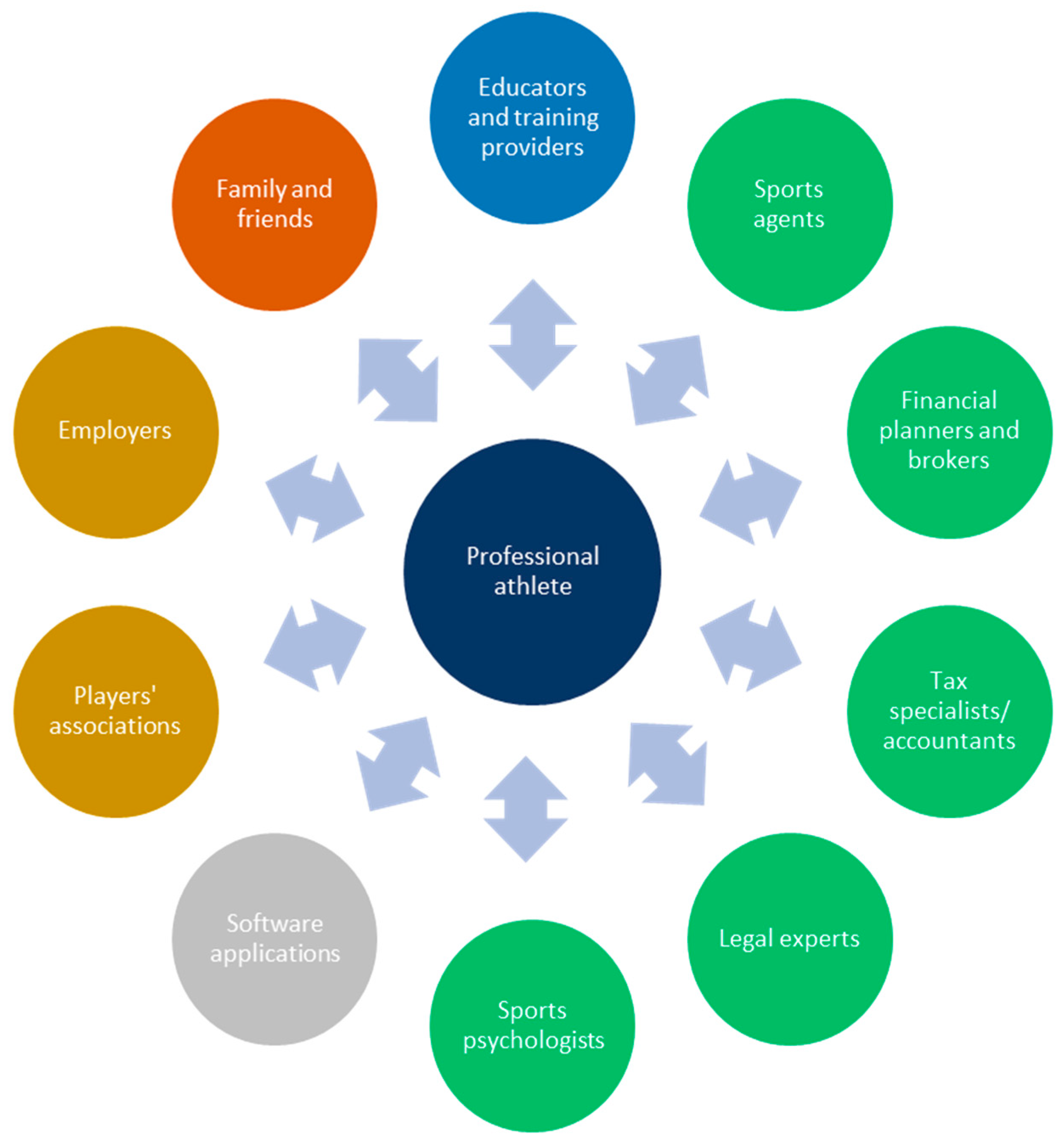

- Moolman, J. (2022). Proposing a network of advisors that could guide a professional athlete’s financial decisions in pursuit of sustainable financial well-being. Managing Sport and Leisure, 27(6), 577–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moolman, J. (2023). Financial literacy content areas for professional athletes: Evidence from a qualitative study. Journal of Financial Counseling & Planning, 34(1), 112–126. [Google Scholar]

- Moolman, J., & Shuttleworth, C. C. (2023). Guidance for professional athletes in selecting a sustainably rewarding player contract. International Journal of Sport Management and Marketing, 23(6), 523–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, J. M. (1994). Designing funded qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin, & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development). (2018). OECD/INFE toolkit for measuring financial literacy and financial inclusion. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/daf/fin/financial-education/2018-INFE-FinLit-Measurement-Toolkit.pdf (accessed on 14 November 2023).

- Owusu, G. M. Y., Koomson, T. A. A., Boateng, A. A., & Donkor, G. N. A. (2023). The nexus amongst financial literacy, financial behaviour and financial well-being of professional footballers in Ghana. Managing Sport and Leisure, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S., Lavallee, D., & Tod, D. (2013). Athletes’ career transition out of sport: A systematic review. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 6(1), 22–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, N., Rijk, K., Soetens, B., Storms, B., & Hermans, K. (2018). A systematic literature review to identify successful elements for financial education and counseling in groups. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 52(2), 415–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potrich, A. C. G., Vieira, K. M., & Mendes-Da-Silva, W. (2016). Development of a financial literacy model for university students. Management Research Review, 39(3), 356–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remund, D. L. (2010). Financial literacy explicated: The case for a clearer definition in an increasingly complex economy. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 44(2), 276–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, S., Khan, H. H., Sarwar, B., Ahmed, W., Muhammad, N., Reza, S., & Ul Haq, S. M. N. (2022). Influence of financial social agents and attitude toward money on financial literacy: The mediating role of financial self-efficacy and moderating role of mindfulness. Sage Open, 12(3), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, L., Lanfranchi, J. B., Lemetayer, F., Rotonda, C., Guillemin, F., Coste, J., & Spitz, E. (2019). Qualitative methods used to generate questionnaire items: A systematic review. Qualitative Health Research, 29(1), 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, D. W., & Safari, M. (2021). Disclosure effectiveness in the financial planning industry. Qualitative Research in Financial Markets, 13(5), 672–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J., & McKenna, S. (2020). An exploration of career sustainability in and after professional sport. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 117, 103314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieger, M. O. (2020). How to measure financial literacy? Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 13(12), 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, L., & McDonald, B. (2013). After the whistle: Issues impacting on the health and wellbeing of Polynesian players off the field. Asia-Pacific Journal of Health, Sport and Physical Education, 4(3), 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandelowski, M. (2001). Real qualitative researchers do not count: The use of numbers in qualitative research. Research in Nursing & Health, 24(3), 230–240. [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski, M., Voils, C. I., & Knafl, G. (2009). On quantitizing. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 3(3), 208–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santini, F. D. O., Ladeira, W. J., Mette, F. M. B., & Ponchio, M. C. (2019). The antecedents and consequences of financial literacy: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 37(6), 1462–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, M., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2023). Research methods for business students (9th ed.). Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Shim, S., Barber, B. L., Card, N. A., Xiao, J. J., & Serido, J. (2010). Financial socialization of first-year college students: The roles of parents, work, and education. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39, 1457–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swart, N. (2016). Personal financial management: The southern African guide to personal financial planning. Juta. [Google Scholar]

- Tracy, S. J. (2010). Qualitative quality: Eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16(10), 837–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Heerden, K. (2018). Waking from the dream. Viking Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Van Rooij, M., Alessie, R., & Lusardi, A. (2024). Financial literacy in the DNB Household Survey: Insights from innovative data collection. Journal of Financial Literacy and Wellbeing, 2, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warmath, D., & Zimmerman, D. (2019). Financial literacy as more than knowledge: The development of a formative scale through the lens of Bloom’s domains of knowledge. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 53(4), 1602–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, C., Van Rooyen, A., Shuttleworth, C., Binnekade, C., & Scott, D. (2020). Wuity as a philosophical lens for qualitative data analysis. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiltshire, G., & Stevinson, C. (2018). Exploring the role of social capital in community-based physical activity: Qualitative insights from parkrun. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 10(1), 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Interviewee Number | Description of the Actor in the Network Around a Professional Athlete | Group (as per Figure 2) | More than Two Years’ Experience |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Certified financial planner® and independent broker | 1 | Yes |

| 2 | Chartered accountant (CA) (SA), associate member of CIMA (ACMA, CGMA) and tax advisor/practitioner | 1 | Yes |

| 3 | Sports agent and qualified lawyer (with experience in local and international dealings and himself a former professional rugby player) who represents professional rugby players | 1 | Yes |

| 4 | Sports psychologist and career development consultant experienced in working with local and international sports teams | 1 | Yes |

| 5 | Chief executive officer at a leading cricket franchise in South Africa | 2 | Yes |

| 6 | Financial manager at a leading rugby union/franchise in South Africa | 2 | Yes |

| 7 | Experienced academic and CA (SA) with experience in the field of financial literacy | 3 | Yes |

| 8 | Experienced academic and CA (SA) with experience in the field of financial literacy | 3 | Yes |

| 9 | Experienced academic and CA (SA) with experience in the field of financial literacy | 3 | Yes |

| 10 | Experienced academic and CA (SA) with experience in the field of financial literacy | 3 | Yes |

| 11 | Former professional cricket player with experience in playing professionally in South Africa, overseas and at international level, together with experience as an executive committee member of a players’ association | 4 | Yes |

| 12 | Current professional rugby player with experience in playing professionally for a leading franchise in South Africa and overseas | 5 | Yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moolman, J.; Shuttleworth, C.C. Qualitatively Pre-Testing a Tailored Financial Literacy Measurement Instrument for Professional Athletes. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 317. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18060317

Moolman J, Shuttleworth CC. Qualitatively Pre-Testing a Tailored Financial Literacy Measurement Instrument for Professional Athletes. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(6):317. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18060317

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoolman, Jaco, and Christina Cornelia Shuttleworth. 2025. "Qualitatively Pre-Testing a Tailored Financial Literacy Measurement Instrument for Professional Athletes" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 6: 317. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18060317

APA StyleMoolman, J., & Shuttleworth, C. C. (2025). Qualitatively Pre-Testing a Tailored Financial Literacy Measurement Instrument for Professional Athletes. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(6), 317. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18060317