4.1. Measurement Model

This study employs SEM (structural equation modeling) to examine robustness as it is regarded as the correct estimation of the underlying model (

J. Hair et al., 2017). To quantify the cause-and-effect relationship among the variables, the explanatory factor analysis and path model analysis were employed using SPSS and Amos Graphics (version 21.00). Moreover, the common method bias and multicollinearity issues will also be measured.

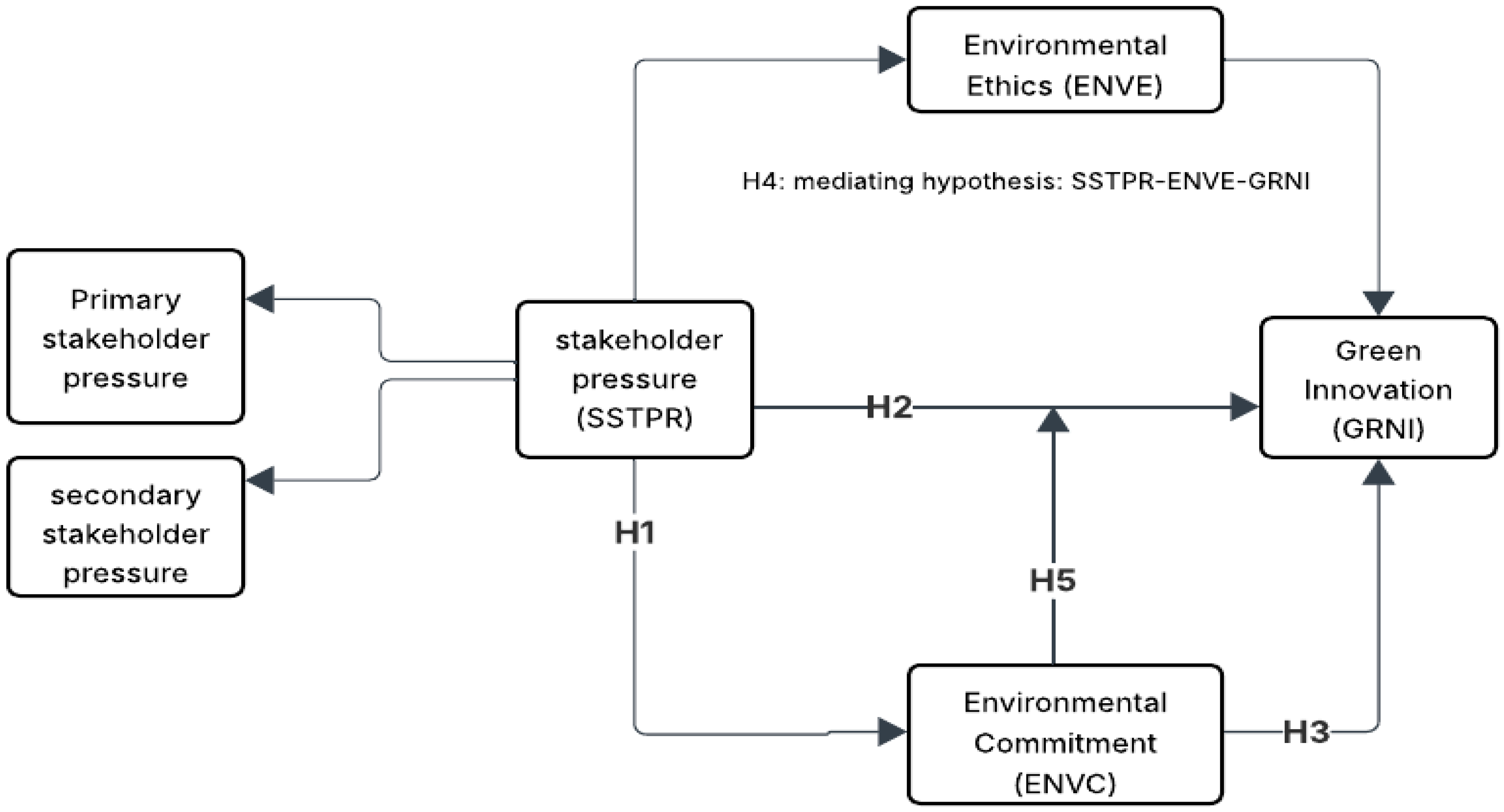

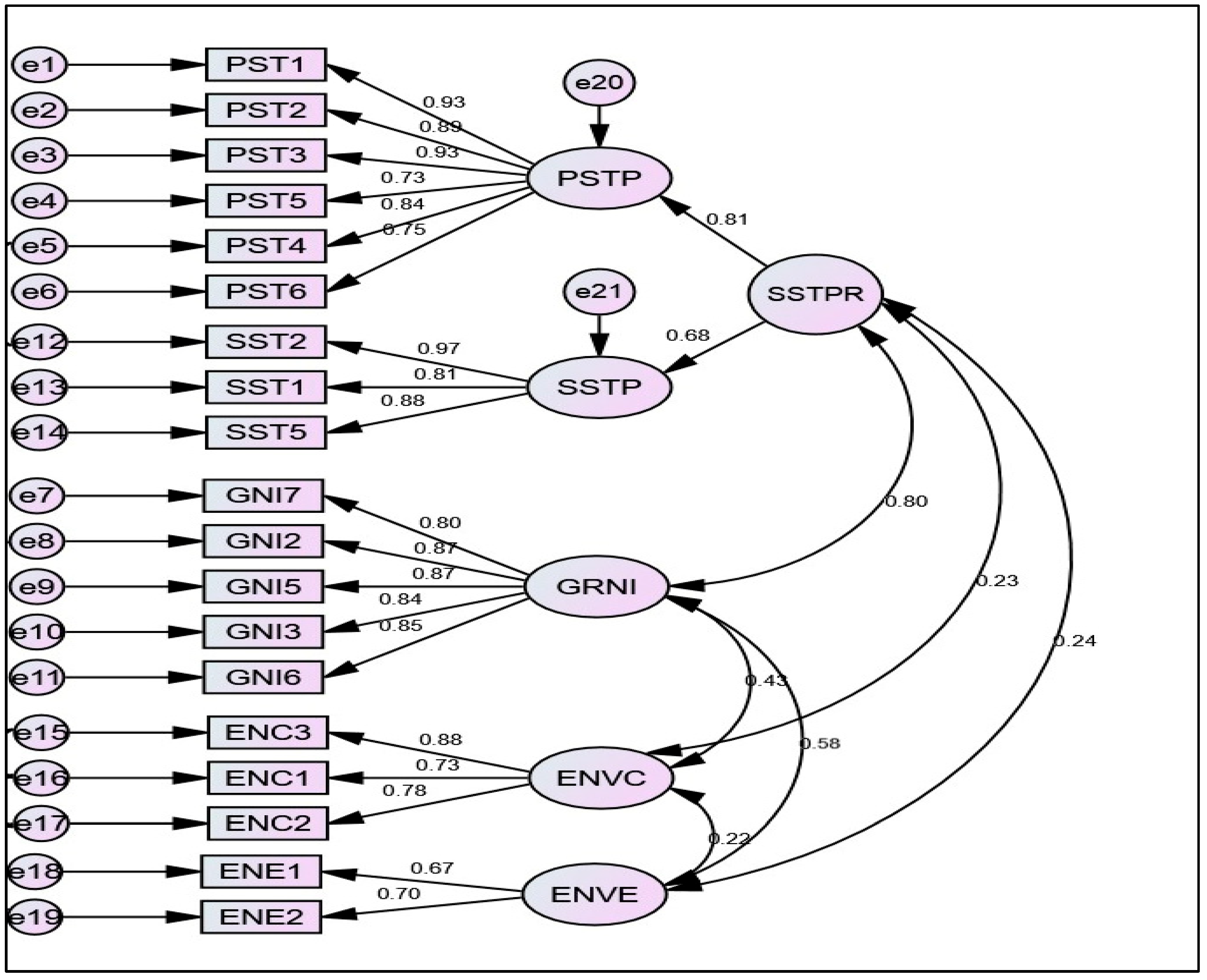

The measurement model was examined to assess the fitness of the intended variables that were studied. Since the dimension of SSTPR is not explicitly distinct to ensure internal consistency of the constructs with others, the EFA (Exploratory factor analysis) presented in

Table 2 reflects a 2-dimensional solution with 9 items. To ensure the model’s authenticity and robustness, the reliability, validity, and CFA were estimated to represent the constructs by taking SSTPR as a second-order construct. Due to poor loadings of the regression weight, 2 items from ENVC and 3 items from ENVE had to drop out, which was employed as a theory-consistent purification step to enhance measurement precision while preserving the conceptual integrity of the ENVC and ENVE constructs.

Figure 2 is illustrated with all the regression weights of the factor analysis, where each construct yields a regression weight of more than 0.70, and the representing variable also depicts a good fit model (χ

2/df = 2.824, GFI = 0.921, AGFI = 0.914, NFI = 0.938, CFI = 0.912, RMSEA = 0.061,

p-value = 0.000) (

J. F. Hair et al., 2014).

Table 3 and

Table 4 illustrate reliability and validity estimation in terms of cross-loading, convergent validity, composite reliability, and discriminant validity to examine the construct’s dependability and validity recommended by (

J. Hair et al., 2017). Indicator loading is known as the relationship between a specific factor and its associated items. Indicator loadings and convergent validity are represented by the outer loadings of the variable items, which should exceed 0.70 for the study to be deemed valid. Furthermore, the reliability score should exceed 0.70, and the Average Variance Extracted (AVE), which also indicates convergent validity, should be approximately 0.50 or higher. The reflective measurement model, along with the results for outer loadings, Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability, and AVE, have met acceptable threshold values.

The table shows that the minimum Average variance extracted (AVE) is 0.626 and 0.755, which are greater than the minimum threshold value of 0.50. The composite reliability is more than 0.70, respectively (

J. F. Hair et al., 2014). The discriminant validity (represented in a diagonal line with bolded values), which exhibits the square root of AVE, is greater than their correlation with other inner constructs. It indicates no issues with discriminant validity (

Fornell & Larcker, 1981). To ensure discriminant validity, each variable’s HTMT Value must be less than 0.90 (

Henseler et al., 2015).

Table 4 discovered discriminant validity. Moreover, the composite reliability is higher than the correlation coefficient of each construct with a cut-off value of 0.7. The correlation of the control variables (firm size and firm age) is also significant. Additionally, the values of Cronbach’s α range from 0.752 to 0.959, which is greater than the threshold value of 0.7 (

Lance et al., 2006). The total variance that accounts for the 4 factors is 83.08. Thus, the above-mentioned criteria result in the conclusion that the model is free from any discriminant validity issues.

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

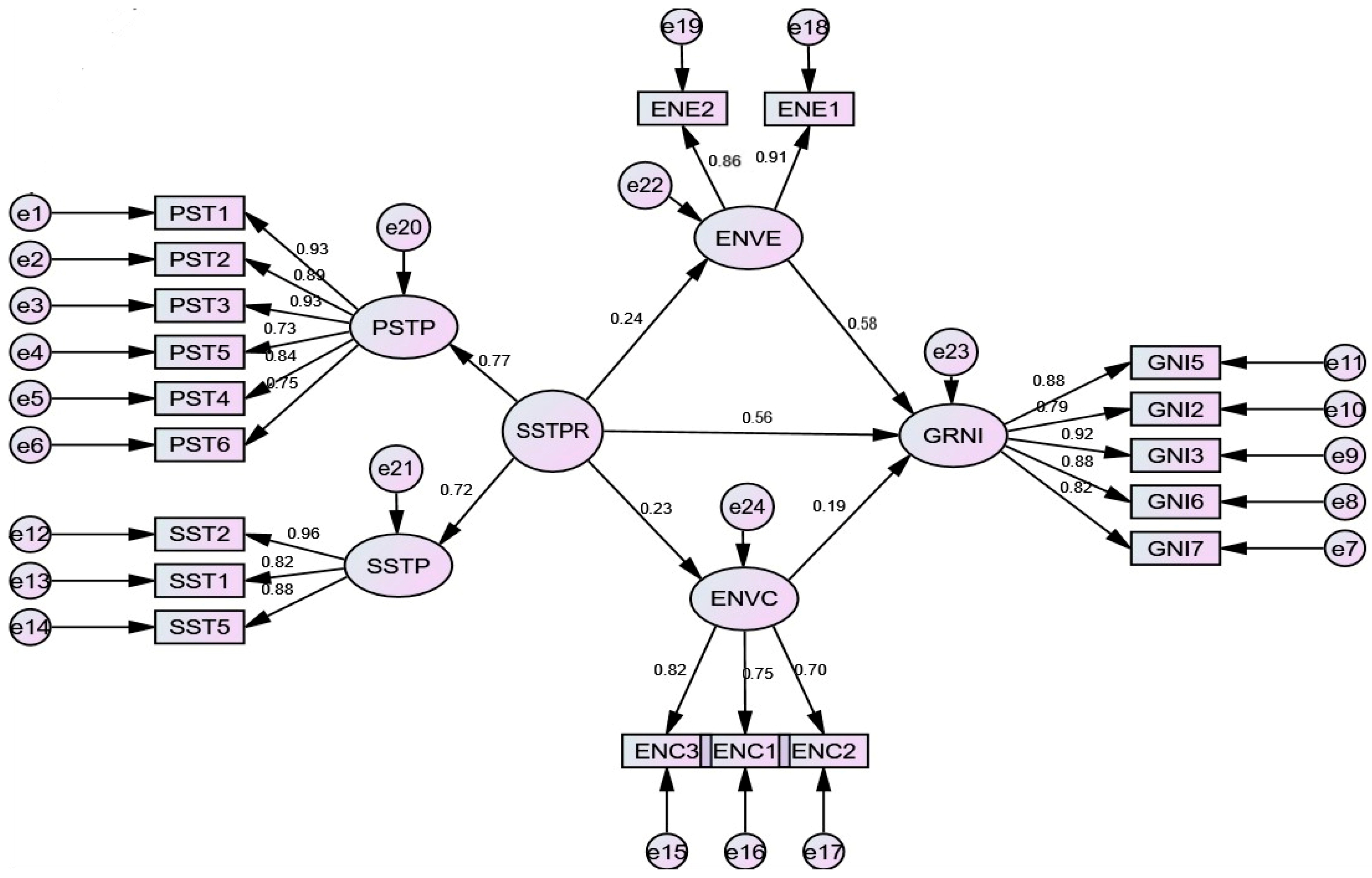

The study employs a structural model equation with a good model fitness, which is represented in

Table 6. The overall fit indices (χ

2/df = 2.546, GFI = 0.936, AGFI 0.911, NFI 0.930, CFI 0.918, TLI 0.910, RMSEA 0.073), which satisfy the value of the suggested range recommended by

J. F. Hair et al. (

2014).

Cohen et al. (

2013) suggest that values of β and R

2 higher than 0.12 are considered satisfactory and suitable for the study. Utilizing 5000 bootstrapping sampling times,

Table 7 shows the value of the β coefficient (

t-values) and the R

2 for ENVC and GRNI (ranging from 0.214 to 0.613) were higher than the onset value of 0.12. Moreover, f

2 values showed in the relationship of the model between the constructions varied from 0.027 to 0.476, and they are presented in

Table 6. An f

2 value higher than 0.02 indicates that the model presents a robust association, although this value close to zero was biased and irrelevant. Hence, f

2 values greater than 0.02 represent the relationship intensity between each independent and dependent variable (

J. Hair et al., 2017).

Here,

Figure 3 represents the structural model equation, and

Table 8 exhibits the results of hypothesis testing through 5 consecutive models. Among the 5 hierarchical models, in model 1, the direct relation between SSTPR (primary and secondary) and ENVC will be represented, and the direct relation between SSTPR (primary and secondary) and GRNI is also represented in model 2, while the relation between ENVC and GRNI will be illustrated in model 3. However, model 4 depicts the effect of SSTPR on GRNI, with ENVE (ENVE) acting as a mediating variable, while model 5 is an augmentation of model 4 where ENVC serves as a moderating variable.

Hypothesis 1 (H1) proposed that SSTPR has a positive influence on ENVC, which was found to be statistically significant (Model 1, β = 0.233, t-value = 2.627, p-value = 0.009). Moreover, H1a and H1b suggest that both PSTP and SSTP have positive influences on ENVC, which was also found to be significant statistically (H1a: β= 0.243, t-value = 2.580, p-value = 0.011; and H1b: β = 0.231, t-value = 2.112, p-value = 0.036).

Again, Hypothesis 2 (H2) proposed that SSTPR has a positive relation with GRNI, which is confirmed as the path between SSTPR and GRNI was found to be significant statistically (Model 2, β = 0.561, t-value = 5.058, p-value = 0.000). Additionally, H2a and H2b suggest that both PSTP and SSTP have a positive influence on GRNI, which was also found to be significant statistically (H2a: β = 0.618, t-value = 7.843, p-value = 0.000; and H2b: β = 0.664, t-value = 8.935, p-value = 0.000).

Furthermore, H3 suggests that ENVC has a positive impact on GRNI, which also results in a significant (Model 3, β = 0.194, t-value = 2.096, p-value = 0.038).

Figure A1 in

Appendix A also illustrates the moderating effect of ENVC on SSTPR and GRNI (H5), on PSTP and GRNI (H5a), and SSTP and GRNI (H5b). H5 suggests that the influence of SSTPR on GRNI is moderated by ENVC, which asserts that the higher appearance of ENVC strengthens the positive influence of SSTPR on GRNI, whereas the lower appearance of ENVC weakens the positive influence of SSTPR on GRNI (Model 5, β = 0.158, t-value = 2.132,

p-value = 0.033) with a positive slope. Similarly, the H5a and H5b were also tested, where H5a was supported (β = 0.612, t-value = 6.429,

p-value = 0.000), affirming that the influence of PSTP on GRNI is moderated by ENVC, which asserts that the higher appearance of ENVC strengthens the positive influence of PSTP on GRNI, whereas the lower appearance of ENVC weakens the positive influence of PSTP on GRNI. However, H5b portrays the positive moderation of ENVC on the relationship between SSTP and GRNI (β = 0.032, t-value = 0.449,

p-value = 0.654), though their relationship is not significant, which does not support the hypothesis, suggesting that firms may not respond to secondary stakeholders unless strongly committed to environmental values. This divergence from Western contexts, where NGOs and media often directly shape firm behavior, emphasizes the contextual role of institutional strength and societal awareness. In weakly institutionalized environments like Bangladesh, secondary stakeholders’ signals may lack enforcement power, and resource-constrained SMEs are likely to prioritize pressures that have immediate strategic or economic consequences. This underscores the need for comparative research across institutional contexts to examine how the relative influence of secondary stakeholders varies between strong and weak institutional environments, and how ENVC interacts with these pressures under differing cultural, regulatory, and resource conditions.

H4 states that ENVE is the mediating variable between SSTPR and GRNI, which was also supported in examining the mediating role of ENVE. At first, this study examined the indirect effect of SSTPR on GRNI through ENVE, and it exhibits a significant effect with a β value of 0.142. Then, the direct effect of SSTPR on GRNI was also examined after removing ENVE as a mediator and found a significant positive impact with a β value of 0.597 (

Table 9), which indicates ENVE complementary partial mediation. The results extracted from the model exhibit that the indirect effect is significant in the presence of a mediator, where the value of the indirect effect path is less than the total effect path, and as a rule of thumb, the relationship between SSTPR and GRNI is partially mediated by the ENVE, which supports the hypothesis (

Ghadi et al., 2013). The value of R

2 increased from 0.443 to 0.548, and the Sobel test was also run to rationalize the mediation effect decision, where the estimate suggests a significant value of indirect effect (z-statistics = 2.121 > 1.96,

p = 0.033 < 0.05). Hence, H4 is supported. However, this contrasts with prior studies where ethics served as the primary mediating pathway, highlighting a context-specific gap likely shaped by Bangladesh’s institutional weaknesses, resource constraints, and socio-cultural norms. Firms may thus rely on a combination of strategic considerations, resource availability, and ethical judgment to respond to stakeholder expectations.