1. Introduction

In recent years, cryptocurrencies have gained popularity due to advantages such as enabling peer-to-peer transactions without intermediary financial institutions and providing secure and private financial transfers (

Mirza et al., 2023). Since Bitcoin’s introduction as a peer-to-peer electronic cash system by

Nakamoto (

2008), the market has expanded significantly, with CoinMarketCap tracking 18.67 million cryptocurrencies as of July 2025 (

CoinMarketCap, 2025). One of the main reasons behind the popularity of cryptocurrencies is their potential to generate substantial long-term profit for investors. For example, Bitcoin’s price has increased roughly tenfold over the last five years, despite experiencing periods of sharp volatility during that time (

Edwards, 2025). As noted by some cryptocurrency supporters, investors also appreciate that cryptocurrencies eliminate the need for central banks to control the money supply, since such banks are often linked to inflation and a decline in money’s value (

Rosen, 2025).

Although cryptocurrencies can yield high returns, they are also highly susceptible to significant losses in value due to the fluctuating nature of the cryptocurrency market. For example, Bitcoin has seen significant collapses, losing 61% of its value in 2014, 73% in 2018, and 64% in 2022, despite growing thousands of percent since its founding (

Royal, 2025). More recently, the crypto market experienced a crash that wiped out over

$19 billion in leveraged positions between 10 and 11 October 2025 (

ArunKumar et al., 2025). During this crash, Bitcoin fell by roughly 13% from its all-time high of over

$126,000, and the impact was even more severe for altcoins, since tokens such as Solana, Sui, and several memecoins lost more than 40% of their value within minutes.

Fluctuations in the value of a cryptocurrency may result from macroeconomic factors that influence the overall financial landscape, while they can also be affected by characteristic parameters of a coin, such as market activity, trading volume, closing price, opening price, and similar indicators. On the macroeconomic side, the classical supply–demand relationship plays a crucial role, as rising demand relative to a fixed supply can drive up the value of cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin (

Rosen, 2025). Conversely, when supply is unlimited and demand falls, prices tend to decrease, and episodes of overselling or overbuying can create sharp market fluctuations (

Tiao, 2025). Moreover, high interest rates might motivate investors to move their money from low-utility or speculative coins to safer assets, such as savings accounts. Similarly, during times of uncertainty, such as wars or economic crises, people tend to avoid risky financial moves, which can affect the cryptocurrency market. According to a case study, the start of the COVID-19 pandemic caused a crypto-rush, followed by an inverse trend as many investors left the market later (

Jabotinsky & Sarel, 2023). In addition to these influences, attempts to interfere with the decentralized nature of cryptocurrencies, such as discussions about bringing regulations to the crypto market by the governments, can result in a decline in their value (

Tiao, 2025).

Such events, triggering fluctuations in the market, can also result in the disappearance of certain cryptocurrencies from the market. Many other factors, such as the level of trust given to investors by the founder of a cryptocurrency, negative social media sentiments, or scandals, can lead to a rapid decline in a coin’s trading volume. For example, a leading cryptocurrency exchange, FTX, crashed in November 2022 after it was revealed that its affiliate, Alameda Research, relied heavily on speculative tokens (

Reiff, 2024). This led to the withdrawals of many customers and the bankruptcy of both companies, causing significant disruption in the cryptocurrency market. Aside from scams, cryptocurrencies that are created as jokes or memes often lose their validity due to lack of practicality, while legitimate coins can become dead coins due to insufficient funding, developer departure, or declining market interest (

Ledger Academy, 2025).These examples illustrate that while cryptocurrencies can be highly profitable, they also expose investors to serious risks such as sharp market drops, unexpected regulatory decisions, and the possibility that a coin may become worthless.

A cryptocurrency that has lost almost all its value or is no longer usable is known as a “dead coin”(

Ledger Academy, 2025). According to industry standards, cryptocurrencies are usually categorized as defunct or “dead” if their trading volume over three months is less than USD 1000 (

Ledger Academy, 2025). Currently, there is not a formal definition of dead coins in the professional and academic literature (

Fantazzini, 2022). Within the scope of this study, a dead coin is defined as a cryptocurrency with no activity within the past year. While there are many external factors affecting the value fluctuations and death of a cryptocurrency, these factors are hard to track and use for future predictions. On the other hand, quantitative parameters of a coin, categorized as time series data, can provide insights into whether the coin will continue to be traded or lose its value over time. These predictions can be useful for investors to manage their cryptocurrency portfolios and minimize potential losses.

In the context of time series, the goal of forecasting is to predict exact values, whereas classification assigns data to distinct categories based on its past behavior. Time Series Classification (TSC) is the task of training a classifier with sequential time series data to learn a mapping from input sequences to a probability distribution over possible class labels (

Fawaz et al., 2019). In many real-world scenarios, especially financial applications, classification of data can be more useful for decision-making than forecasting. This change in approach has led to the development of many TSC methods, particularly for use in finance.

This study places special emphasis on classifying time series data by predicting whether a cryptocurrency will become dead within the upcoming 10-day period. By analyzing the risk of cryptocurrencies’ dying, investors can reduce potential losses and enhance their portfolio management strategies. The classifications were based solely on the coins’ characteristics, specifically daily closing prices and trading volumes. We retrieved the time series data used in this study from Nomics

1.

Historically, TSC problems have been solved with various methodologies such as

k-Nearest Neighbors (

k-NN) and Dynamic Time Warping (DTW) (

Abanda et al., 2019;

Wang et al., 2018). In more recent years, machine learning and deep learning methodologies have surfaced, and they have been used for many time series forecasting and classification problems. Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) are particularly useful for capturing temporal patterns between data; hence, they are commonly used for sequential prediction problems (

Tessoni & Amoretti, 2022). In a study comparing various machine learning and deep learning models for forecasting Bitcoin price trends, RNNs were found to outperform other architectures, highlighting their effectiveness for cryptocurrency-related prediction tasks (

Goutte et al., 2023). Among them, the Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) and Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) models demonstrated particularly strong performance, further supporting their suitability for modeling financial time series data. Therefore, LSTM, GRU, and Bidirectional LSTM (BiLSTM) architectures, which are specific forms of RNNs, are selected in this study to assess their performance in predicting the risk of cryptocurrencies becoming dead coins.

The main objectives of this study can be summarized as follows:

Creating variations of deep learning models using LSTM, GRU, and BiLSTM architectures by systematically altering the number of layers and units per layer to analyze their impact on predictive performance.

Extending financial risk theory by framing cryptocurrency failure as a time series classification problem rather than a forecasting task, linking the concept of “death risk” to survival analysis perspectives within cryptocurrency markets.

Training these models with time series data of trading volume and closing price values of cryptocurrencies to predict the risk of a coin becoming dead within the following 10 days and selecting the best-performing model for each architecture.

Providing a data-driven warning system that helps investors and portfolio managers spot coins showing early signs of inactivity or collapse and offering timely information for safer risk-management and investment decisions in a highly volatile market.

Improving methodological understanding by systematically comparing LSTM, GRU, and BiLSTM architectures under consistent experimental conditions and multiple historical input windows of 10 to 180 past days to evaluate how the length of past data influences the performance of predicting a coin’s death risk within the following 10 days. The comparative results clarify how network depth, bidirectionality, and gating mechanisms influence performance when modeling financial time series with irregular activity patterns, providing guidance for applying deep learning to risk assessment in volatile markets such as cryptocurrencies and other emerging financial assets.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 gives insights about the related workworks in the literature.

Section 3 describes the dataset used in the study and its related preprocessing steps along with deep learning architectures used in the experiments.

Section 4 and

Section 5 outlines the details of the experiment procedure and analyzes the results. Finally, the study is concluded with

Section 5, explaining theoretical and practical implications, limitations, and suggestions for future work.

2. Review of Literature

Data instances recorded sequentially over time are referred to as time series data, which consist of ordered data points that carry meaningful information (

Fawaz et al., 2019). Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) are the most widely used machine deep learning models for sequential prediction problems (

Tessoni & Amoretti, 2022). Within the family of RNNs, Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) and Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) architectures are widely used for modeling long-term dependencies in time series data, as they effectively address challenges such as vanishing gradients (

Hochreiter & Schmidhuber, 1997). These architectures have become popular for time series forecasting applications due to their ability to capture complex temporal patterns. Financial forecasting is also a key area that benefits from historical financial time series data to predict trends in the market and provide strategical insights to investors and speculators (

Tang et al., 2022). For instance,

Fister et al. (

2021) developed LSTM-based models for stock trading, achieving robust portfolio performance in the German financial market. Similarly,

Sivadasan et al. (

2024) trained LSTM and GRU networks using the technical indicators (TIs) and open, high, low, and close (OHLC) features of various stocks to predict the opening prices of the stocks for the following day. In this study, GRU achieved higher accuracy in most cases, reducing Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) to 0.62% for Google stock, compared to LSTM’s 1.05%. Likewise,

Lawi et al. (

2022) constructed eight models with different preprocessing and regularization steps for forecasting the stock prices of the companies AMZN, GOOGL, BLL, and QCOM. Although the models showed competing performance, it was significant that the four models combined with GRU outperformed the other four models combined with LSTM on the stock prices of AMZN, GOOGL, BLL, and QCOM, with accuracies of 96.07%, 94.33%, 96.60%, and 95.38%, respectively.

Time series analysis can be applied to study cryptocurrency performance, and many studies already focus on forecasting their future values. Some of these studies propose hybrid deep learning approaches for cryptocurrency price prediction. For example,

Patel et al. (

2020) proposed a hybrid model combining LSTM and GRU to forecast Litecoin and Monero prices over the next 1, 3, and 7 days. Although the proposed model did not present an effective result for the next 7 days, it outperformed traditional LSTM by reducing the Mean Squared Error (MSE) from 194.4952 to 5.2838 for Litecoin and 230.9365 to 10.7031 for Monero for 1-day forecasts, demonstrating strong performance in short-term price prediction. In another research,

Dip Das et al. (

2024) integrated the encoder–decoder principle with LSTM and GRU along with multiple activation functions and hyperparameter tuning for trend predictions in the stock and cryptocurrency market. For various individual stocks, stock index S&P, and Bitcoin as a cryptocurrency, autoencoder–GRU (AE-GRU) architecture significantly outperformed autoencoder–LSTM (AE-LSTM) architecture, with a higher prediction accuracy. In particular, AE-GRU obtained 0.5% MAPE for Bitcoin trend prediction, which is half of the value found with AE-LSTM. In another study, four methods, including a convolutional neural network (CNN), hybrid CNN-LSTM network (CLSTM), multilayer perceptron (MLP), and radial basis function neural network (RBFNN), were compared to predict the trends of six cryptocurrencies, including Bitcoin, Dash, Ether, Litecoin, Monero, and Ripple, within the next minute using 18 technical indicators. For all cryptocurrencies, CLSTM outperformed other architectures, with an accuracy of 79.94% on Monero and 74.12% on Dash cryptocurrencies (

Alonso-Monsalve et al., 2020).

In another study,

Fleischer et al. (

2022) examined the performance of LSTM in predicting the prices of Electro-Optical System (EOS), Bitcoin, Ethereum, and Dogecoin cryptocurrencies only using their historical closing prices. The results were compared to the ARIMA approach using the RMSE (Root Mean Squared Error) metric. LSTM outperformed ARIMA for all cryptocurrencies, showing a 72–73% reduction in RMSE for EOS and Dogecoin, which have greater fluctuations in their closing prices compared to Bitcoin and Ethereum, demonstrating that LSTM performs significantly well for highly volatile cryptocurrencies. In a comparative study,

Seabe et al. (

2023) implemented LSTM, GRU, and BiLSTM, trained on the daily closing prices of Bitcoin, Ethereum, and Litecoin cryptocurrencies in the last five years to forecast their prices. RMSE and the MAPE performance metrics were used to analyze the performance of the models, and BiLSTM surpassed other models with a MAPE value of 0.036 for Bitcoin, 0.124 for Ethereum, and 0.041 for Litecoin. In another study by

Golnari et al. (

2024), a probabilistic approach referred to as Probabilistic Gated Recurrent Unit (P-GRU) was proposed, incorporating stochasticity into the traditional GRU by enabling the model weights to have their distinct probability distributions in order to tackle the challenge coming from the volatile nature of cryptocurrencies, focusing on the prediction of Bitcoin prices. This novel method outperformed the other simple, time-distributed, and bidirectional variants of GRU and LSTM networks. The study was also expanded to predict the prices of six other cryptocurrencies by using transfer learning with the P-GRU model, contributing to the overall inquiry for cryptocurrency price prediction.

In line with our study,

Özuysal et al. (

2022) proposed a method for assessing the death risk of cryptocurrencies over 30, 60, 90, 120, and 150 days, based on their past 30-day data of closing prices and daily trading volumes. In this study, a simple RNN architecture was used for capturing temporal patterns in the data. The study showed that the probability of identifying dead cryptocurrencies increases with longer prediction windows, starting from roughly 37% for the prediction of death in the next 30 days, and reaching nearly 84% for the 150-day horizon. Building on this research,

Sakinoğlu and Güvenir (

2023) proposed and experimented with four different techniques for constructing training datasets for an LSTM model to predict whether a cryptocurrency will die within the next 30 days. However, from the investors’ point of view, it is more valuable to estimate the risk in the near future. Building on these, our study applies special forms of RNNs to predict the death risk of cryptocurrencies in the following 10 days using varying number of input days. By providing short-term predictions, this approach may help protect investors from the risk of holding cryptocurrencies that are likely to fail rapidly.

3. Materials and Methods

The data preprocessing steps and methodology used are described in the following subsections.

3.1. Data Description and Preprocessing

The dataset

2 is composed of time series data for cryptocurrencies that died by 1 March 2023. We found 7312 such cryptocurrencies. According to our definition, the last transaction on these dead cryptocurrencies occurred before 1 March 2022. The dataset includes daily trading volume and closing price values for these cryptocurrencies, collected from a commercial data source.

Each cryptocurrency in the dataset spans a period longer than 18 months, including at least 180 days of trading activity followed by 12 months of complete inactivity. The 180-day portion represents the historical input window used for model training, while the subsequent inactive year verifies the classification of the coin as “dead”. Hence, the total available data for each coin exceeds the prediction horizon, and the labeling process remains temporally consistent.

Even though cryptocurrency markets operate continuously, some coins, especially the ones that are getting close to inactivity, show days where no transactions are recorded. As a result, there are missing entries in the dataset which reflects days without any trading activity. During preprocessing, missing volume values were set to zero and missing closing prices were replaced with the most recent available closing price.

In order to be used in the experiments, time series data for at least days are needed, where is the number of past days and is the number of future days. Only cryptocurrencies that have lived for at least 180 days, providing sufficient historical data to generate both positive and negative instances for the largest input window (), are included in the experiments; currencies with shorter lifespans are removed. In all experiments, , since we are interested in predicting if a cryptocurrency will die in the next 10 days. The values we experimented with are 10, 20, 30, 60, 90, 120, 150, and 180. Since both the volume and closing price values have large differences among the cryptocurrencies, we applied z-score normalization to each volume and closing price data for each remaining cryptocurrency.

The problem is to estimate how accurately we can predict if a cryptocurrency will die in the next

days, given its time series data from the past

days. In preparing the dataset, we opt to have a balanced number of positively and negatively labeled time series data. A positive instance represents the time series data of a cryptocurrency that will live less than

days; similarly a negative instance represents the data of a cryptocurrency that will live

days or more. Given the time series data for a cryptocurrency,

positive (P-labeled) and the same number of negative (N-labeled) instances are created, as shown in

Figure 1. Each instance consists of the time series data with a length of

days. Positive instances are formed from the last

days, while negative instances are randomly selected from the previous days.

The number of cryptocurrencies with sufficient data and the number of instances created for each experiment are shown in

Table 1.

3.2. Methodology

Three specialized RNN architectures, LSTM, BiLSTM, and GRU, were used in this study. Their respective model structures are explained in detail in the following subsections.

3.2.1. Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM)

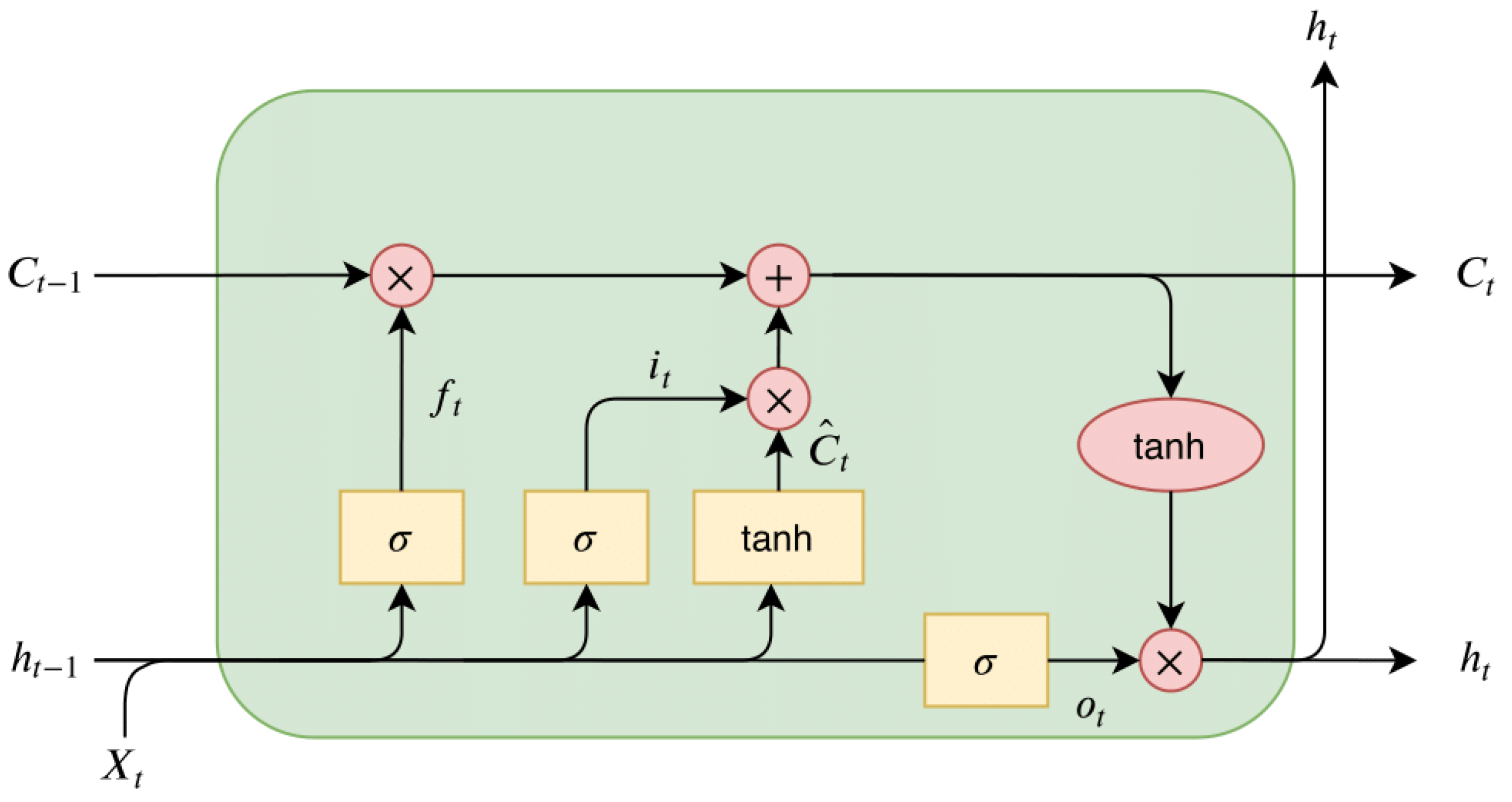

LSTM is a type of RNN, addressing the vanishing gradient problem of conventional RNNs. The architecture of the LSTM cell is displayed in

Figure 2. The diagram highlights how the architecture preserves long-term dependencies (

Ingolfsson, 2021). The forget gate

selectively removes data that are no longer relevant in the cell state by applying a sigmoid function to the current input

and the previous hidden state

. Outputs near 0 lead to forgetting, while values near 1 retain information. The input gate

adds new information to the cell state by first applying a sigmoid function to

and

, determining which values to update. It uses a sigmoid function to filter relevant information and combines it with a candidate vector generated via tanh to update the memory. The final cell state update

is computed by the following equations:

where

are learned parameters (weights and biases).

The output gate

determines what information from the cell state is passed on as output. It applies a tanh function to the cell state and filters the result using a sigmoid gate based on

and

using the following equations:

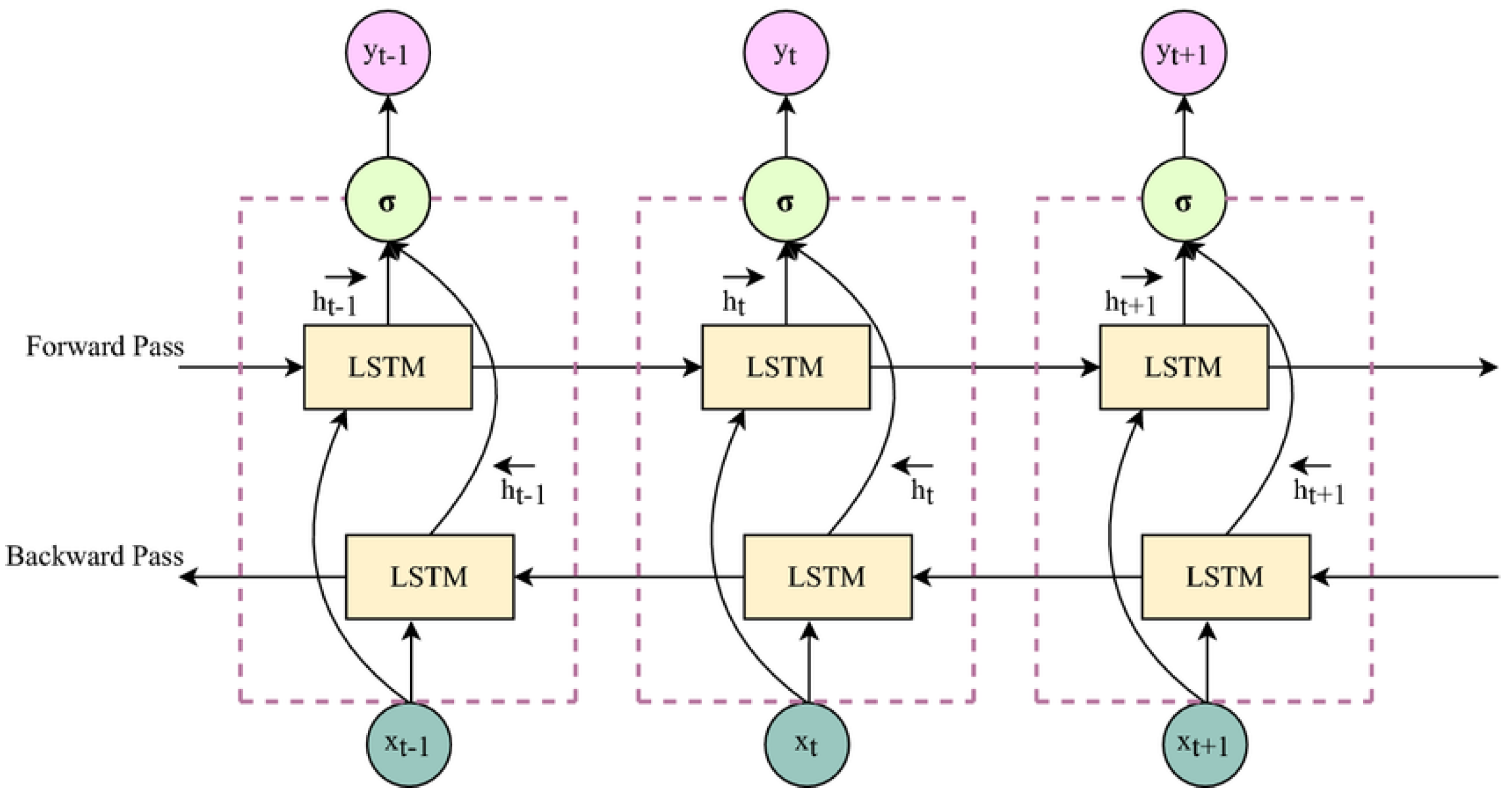

3.2.2. Bidirectional LSTM (BiLSTM)

Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory, or BiLSTM, is a powerful RNN that can process sequences both forward and backward. It improves performance on tasks containing sequential data by capturing both past and future contexts through the use of two distinct LSTM layers, one for each direction. BiLSTM architecture is illustrated in

Figure 3. This bidirectional design enables the model to learn contextual information from previous and future time steps simultaneously (

Naik & Jaidhar, 2022).

3.2.3. Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU)

GRU is a type of RNN designed to capture temporal dependencies in sequential data while using a simplified gating mechanism compared to LSTM. The architecture of the GRU cell is depicted in

Figure 4. GRU The figure shows how GRU simplifies the LSTM architecture while retaining the ability to capture temporal dependencies (

Huang et al., 2019). GRU updates its hidden state based on the current input

and the previous hidden state

, processing sequential data one element at a time. Using these elements, a candidate activation vector

is calculated at each time step. The hidden state is then updated for the following time step using this candidate vector.

Candidate activation vector

is computed using the update gate

and the reset gate

. The update gate balances the contribution of the candidate vector and the previous hidden state

, while the reset gate determines how much of the old hidden state to forget. Final hidden state

is calculated using the following equations:

where

are learned parameters (weights and biases).

4. Experiments and Results

The evaluation procedure employed stratified five-fold cross-validation to ensure balanced representation of both active and dead coins in each fold. In each run, four folds were used for training and one for testing, and this process was repeated five times. The reported accuracy and AUC values are the averages across the five folds. All models were trained and evaluated on the same cross-validation splits to allow direct performance comparison. Standard deviations of the cross-validated accuracies were computed to assess the consistency of results.

For each of the LSTM, BiLSTM, and GRU experiments, we used 500 training epochs, a batch size of 64, and a validation split of 0.2. The number of layers and units per layer varied to find the highest accuracy for each model. To avoid overfitting, early stopping with a patience of 50 was applied based on validation accuracy, dropout layers with a rate of 0.2 and L2 weight regularization were used, and model selection was performed according to validation rather than training performance. For each combination of the number of layers and units per layer, the number of days used as input was varied with the following values

. The performance of the models was evaluated using the average accuracy values across validation steps.

and

represent the accuracy and Area Under Curve obtained for

d number of days used in training, respectively. AUC was calculated to assess the model’s ability to rank cryptocurrencies according to their likelihood of dying. To investigate overall performance across varying input lengths, the average accuracy and average AUC across all input window sizes were computed for each combination of layer and unit configurations as in the following equations:

These metrics form the fundamental basis for comparing model performance.

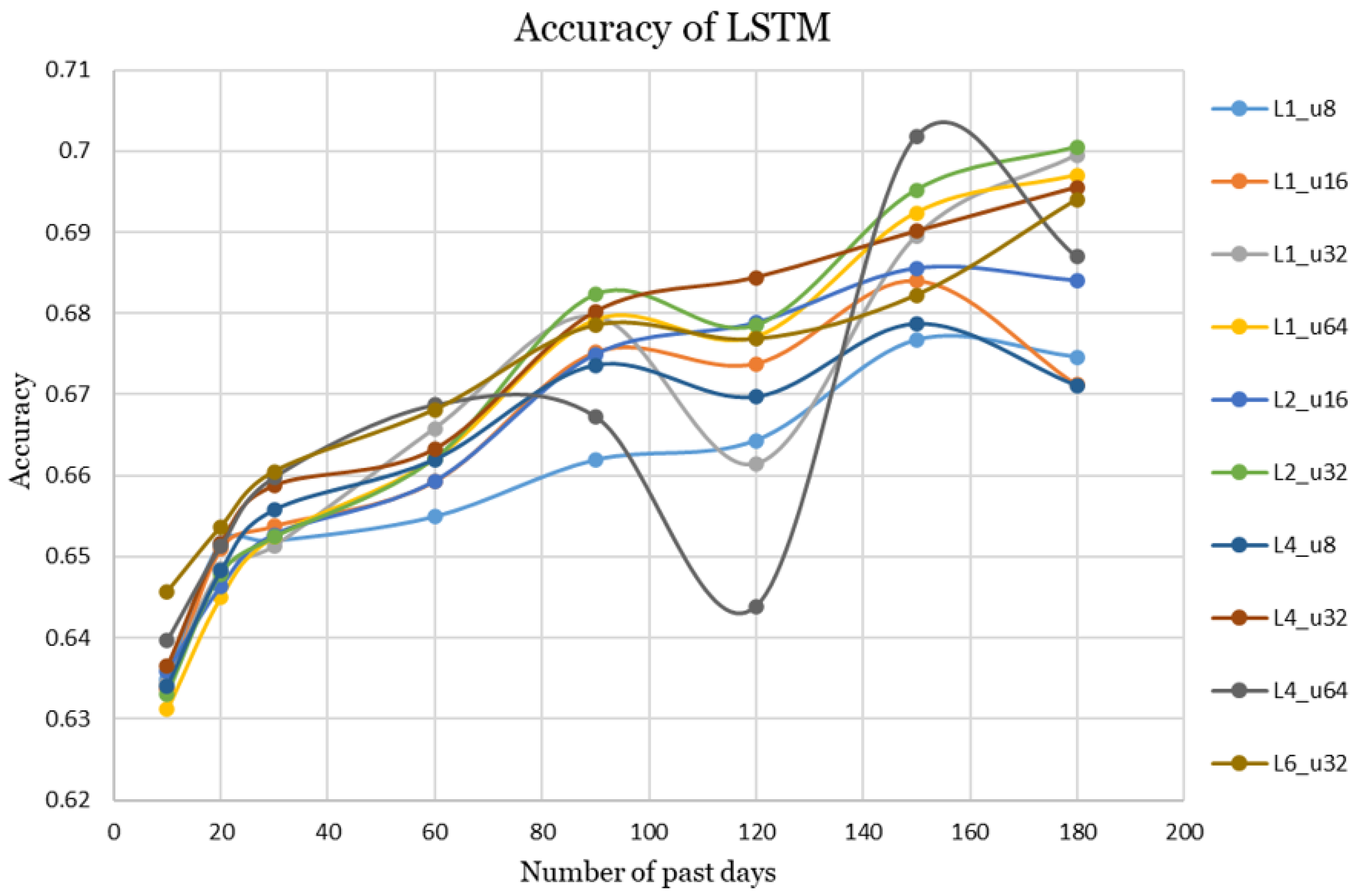

4.1. LSTM

For LSTM, a total of ten different combinations of layer and unit per layer configurations were tested, and the best-performing ones out of these configurations are presented in

Table 2. The highest accuracy and overall AUC values in the table are shown in bold. Each entry represents the mean ± standard deviation of the evaluation metrics obtained from the five-fold stratified cross-validation procedure. The relatively small standard deviations (typically below ±0.02) confirm the stability of the LSTM models across folds. The highest accuracy of 0.7018 was achieved with four layers and 64 units. Although it yielded the highest point accuracy, the corresponding accuracy curve exhibited significant fluctuations, which led to a lower overall AUC value compared to other configurations. Meanwhile, the highest overall AUC of 0.7689 was obtained with one layer and 32 units.

The accuracy curves of different numbers of layers and units are displayed in

Figure 5. The figure shows how accuracy generally increases with longer historical windows but varies by number of layers and number of units per layer. As illustrated, an accuracy of approximately 0.63 was achieved using a 10-day historical window. As the window size gradually increased up to 180 days, a general upward trend in accuracy was observed. The performance of the LSTM architecture is notably influenced by the number of layers and units, which leads to distinct characteristics in the resulting accuracy curves. The configuration with four layers and 64 units per layer achieved the highest accuracy of 0.7018; however, the corresponding curve exhibited a substantial drop around the 120-day mark, indicating potential instability. To reduce the impact of such an instability and to evaluate overall performance across varying historical window sizes, the average accuracy was calculated. The LSTM configuration with four layers, each containing 32 units, achieved the best accuracy,

= 0.6701, and the highest AUC,

= 0.7293, making it the best-performing LSTM network across varying numbers of past training days.

4.2. GRU

For GRU configurations, a single-layer architecture was tested with a different number of units per layer, ranging from 8 to 176. The highest accuracy values from these configurations were achieved by the mid-range configurations. These values are shown in

Table 3. Each result shows the mean ± standard deviation of the evaluation metrics obtained through the five-fold stratified cross-validation. The GRU models exhibited slightly higher stability across folds, with standard deviations lower than 0.011 compared to values up to 0.018 for the LSTM models. The configuration with 96 units gave the highest values for both accuracy and overall AUC, which are 0.7134 and 0.7817, respectively.

Among the multi-layer GRU configurations, only the two-layer and four-layer setups with 32 units per layer were included in the final graph, as they outperformed other multi-layer GRU variants. However, increasing the number of layers did not improve the performance of the GRU, as the highest accuracy values were consistently achieved with single-layer architectures, as shown in

Table 3. The accuracy curves of all the GRU architectures considered are illustrated in

Figure 6. The figure illustrates the gradual improvement in accuracy with longer input windows. The curves exhibited minor fluctuations, indicating a near-linear trend in accuracy rising from approximately 0.63 to 0.71. The single-layer configuration with 96 units per layer achieved the highest accuracy of

= 0.6759, along with the highest AUC of

= 0.7385 across all varying past training days.

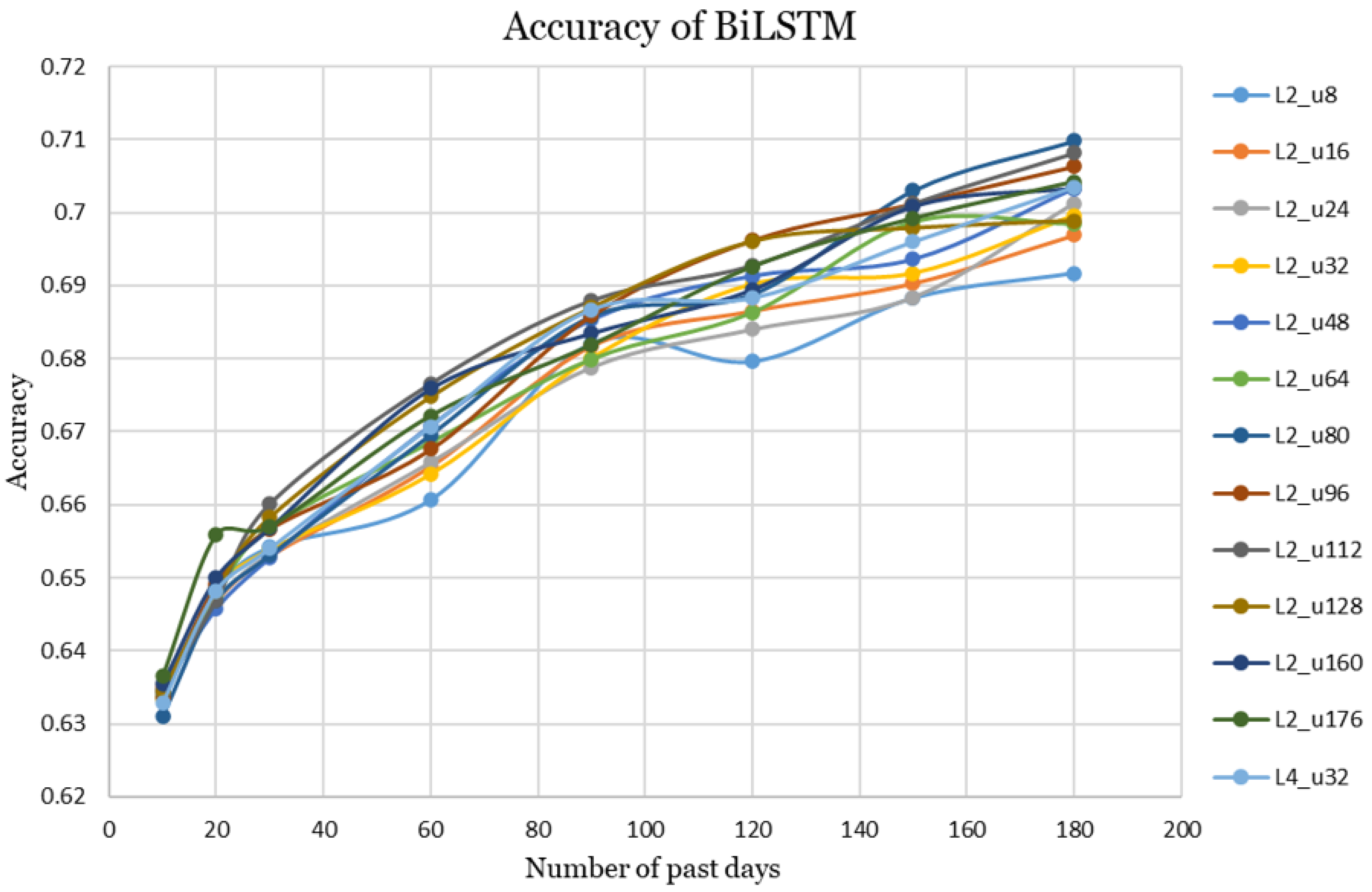

4.3. BiLSTM

For BiLSTM configurations, four variants were evaluated, which are one-layer with averaged hidden states, two-layer with averaged hidden states, one-layer with concatenated hidden states, and two-layer with concatenated hidden states, respectively. Among these, the two-layer averaged configuration achieved the highest average accuracy; hence its results are presented in the analysis.

The BiLSTM experiments included a two-layer architecture evaluated with 12 different numbers of units per layer, ranging from 8 to 176. In addition, a four-layer configuration with 32 units per layer was tested based on the promising results observed in the LSTM experiments. However, this setup did not yield the best performance for BiLSTM. The highest accuracy values obtained for BiLSTM are presented in

Table 4. Reporting the mean ± standard deviation from the five-fold stratified cross-validation, the results showed that the BiLSTM models also achieved consistent performance, with standard deviations consistently lower than ±0.02. The configuration with 80 units per layer achieved the highest point accuracy of 0.7098, whereas the configuration with 112 units per layer yielded the highest overall AUC of 0.7801. Both results were obtained using 180 past days as input.

The accuracy curves for all tested BiLSTM configurations are presented in

Figure 7 to illustrate their comparative performance across varying historical window sizes. The results show overall improvement with longer historical windows and strong performance from several two-layer architectures.The best-performing configuration based on the average accuracy and AUC values for varying past training days was the two-layer BilSTM with 112 units per layer. This configuration achieved an accuracy of

= 0.676 and AUC of

= 0.7377. The remaining configurations produced closely comparable results.

4.4. Performance Summary

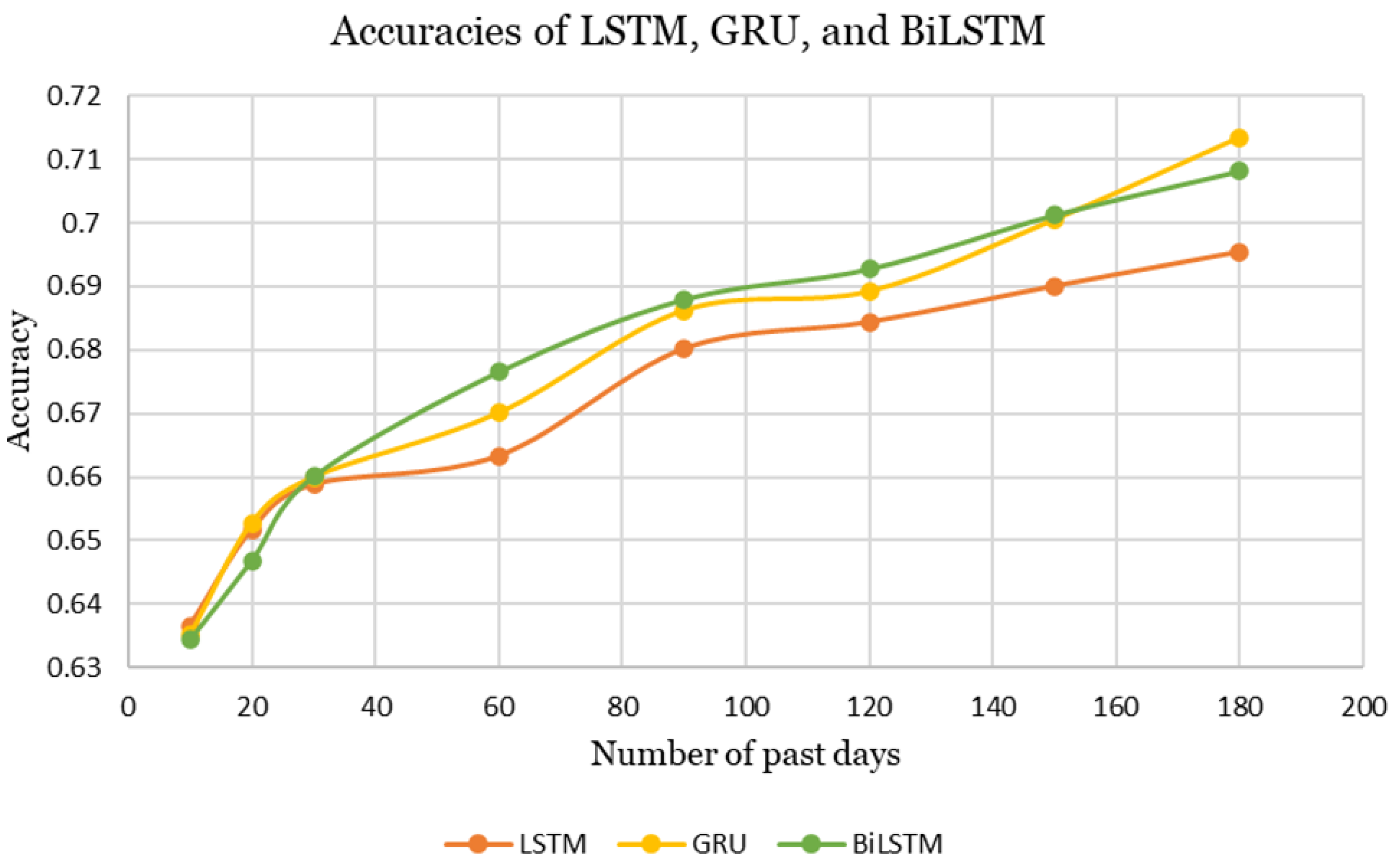

The best-performing configurations of LSTM, GRU, and BiLSTM are illustrated in

Figure 8. Overall, all architectures exhibit an upward trend in accuracy, increasing from approximately 0.63 to 0.71 as the number of past days increases.The figure summarizes how all architectures achieve increasing accuracy with longer input histories, with BiLSTM slightly outperforming the others on average.

The average accuracy and AUC values for the best-performing configurations of LSTM, GRU, and BiLSTM are summarized in

Table 5. Based on these metrics, BiLSTM slightly outperformed the other models in terms of accuracy across varying number of past training days.

5. Conclusions

This study examined how recurrent deep learning architectures can be used to estimate the short-term failure risk of cryptocurrencies. By analyzing daily closing prices and trading volumes of more than seven thousand coins, three models, LSTM, GRU, and BiLSTM, were evaluated with accuracy as the primary evaluation metric. The models produced similar accuracy values overall. However, LSTM exhibited the lowest accuracy and the most fluctuating performance among the experiments. On the other hand, GRU achieved the highest point accuracy of 0.7134 with a 180-day input window, while BiLSTM demonstrated the best overall performance across varying input lengths with an average accuracy of 0.676. These findings demonstrate that Recurrent Neural Networks can capture temporal dependencies in cryptocurrency data and provide reliable early-warning signals for potential failures. The conclusions of the study are discussed under three perspectives: theoretical implications, practical implications, and research limitations with future directions.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

The death of a cryptocurrency can be influenced by two distinct categories of factors: intrinsic characteristics of the coin itself, such as closing price, trading volume, and market activity, and external macroeconomic conditions that shape the broader financial environment. This study contributes to the theoretical literature by reframing cryptocurrency failure prediction as a time-series classification problem, extending survival-analysis concepts into the digital-asset domain. The comparative evaluation of LSTM, GRU, and BiLSTM architectures enhances understanding of how recurrent neural networks model nonlinear dependencies and volatility in financial data. For all three models, accuracy improved as the number of past days used as input increased, showing that having more historical data makes the predictions more reliable. The models produced similar accuracy values overall. However, LSTM exhibited the lowest accuracy and the most fluctuating performance between the experiments. On the other hand, GRU achieved the highest point accuracy of 0.7134 with a 180-day input window, while BiLSTM demonstrated the best overall performance across varying input lengths. Furthermore, no clear correlation was observed between the number of layers and the number of units per layer for any of the models. The optimal model configuration can be identified through exploration of various architecture combinations. These observations strengthen theoretical knowledge of RNNs and validate their relevance to financial risk modeling.

5.2. Practical Implications

From a practical standpoint, the models developed in this study provide a data-driven early-warning framework for investors, portfolio managers, and exchanges. Overall, our findings suggest that it is possible to predict that a cryptocurrency will die in the next 10 days with roughly 70% accuracy by analyzing its performance over the last six months. This window provides investors with sufficient time to assess risk and sell the cryptocurrency they hold before a potential failure, allowing early liquidation of vulnerable assets. The system can also help cryptocurrency exchanges and regulators identify coins that are becoming risky or difficult to trade. Although cryptocurrencies lack formal redemption mechanisms, sudden spikes in trading volume often resemble a digital version of a “bank run” behavior, signaling potential collapse. Detecting such patterns can guide risk management in highly volatile crypto markets.

5.3. Research Limitations and Future Work

Despite promising results, the study has several limitations that point to future research opportunities. Although macroeconomic factors may influence the death of a cryptocurrency, many are difficult to track or quantify due to limited data availability. This constraint represents a limitation of the present study, which therefore focuses on closing prices and trading volumes, as they are more consistent and accessible for cryptocurrencies.

There are several different definitions for the death of a cryptocurrency (

Fantazzini, 2022). We chose the definition as transaction inactivity for at least one year. This is the limitation of this work based on the definition of dead cryptocurrency. As long as the time series data about the daily transactions for a cryptocurrency can be converted into positive and negative labeled time series instances, the methodology used in this study can be applied to any definition of dead cryptocurrencies.

Incorporating factors such as sentiments of investors, developer activity, and regulatory announcements could improve model robustness. Furthermore, experimenting with historical windows longer than 180 days and training the models with a larger number of cryptocurrencies may enhance generalizability and better capture long-term trends in a cryptocurrency’s behavior. Future work may also investigate, hybrid architectures that combine LSTM, GRU, and BiLSTM components to potentially achieve improved predictive performance. Although the models in this study were treated as predictive black boxes, understanding their decision process is an important future goal. The predictions are driven by temporal patterns in closing prices and trading volumes, yet the specific contributions of these variables were not analyzed in detail. Future research will focus on incorporating explainable AI methods such as SHAP values, attention visualization, or gradient-based attributions to show which time-based patterns have the strongest impact on the model’s predictions. Finally, early liquidity withdrawals or redemption-like signals could be found by examining transaction-level or on-chain data, connecting theoretical models with real market activity.