The Impact of Corporate Biodiversity Information Disclosure on Green Investment Confidence and Willingness of Retail Investors in China: The Moderating Roles of Risk Aversion and Climate Risk Awareness

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

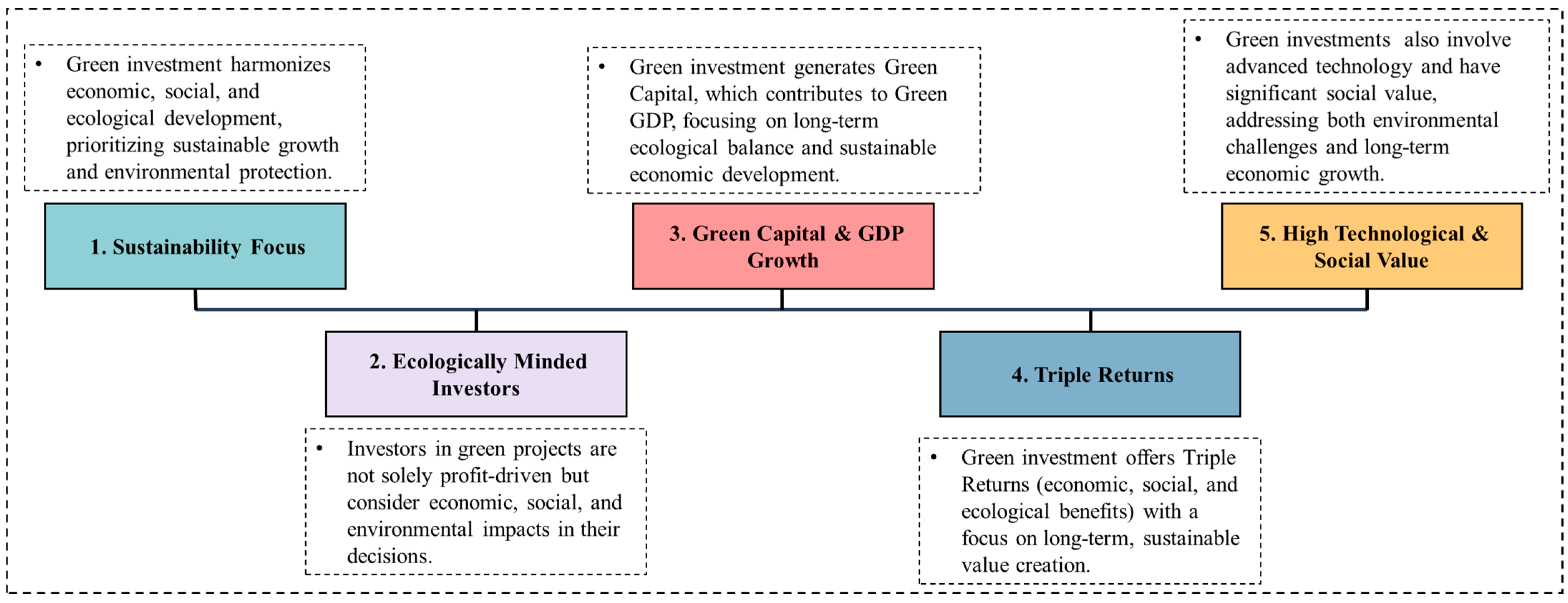

2.1. Green Investment

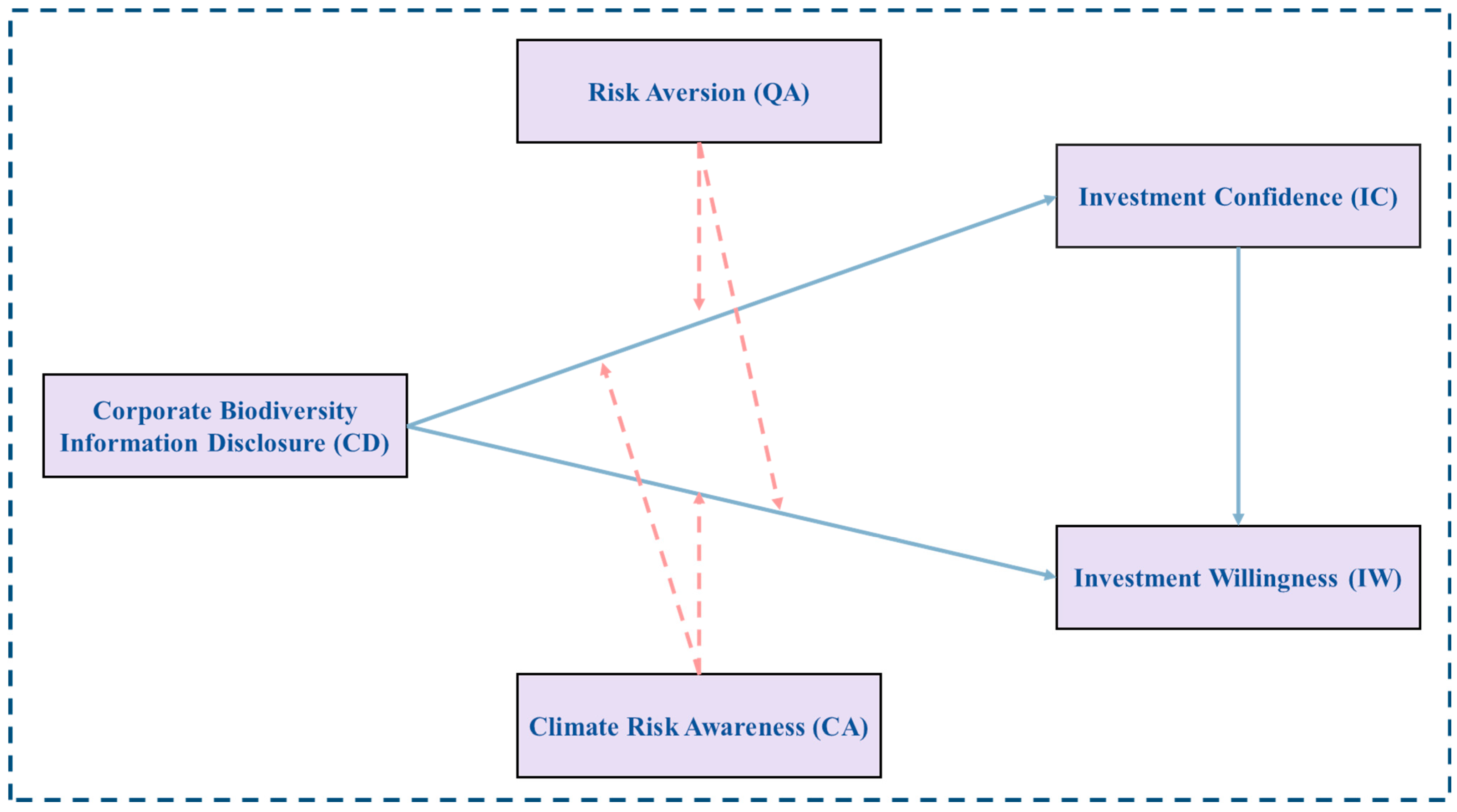

2.2. Corporate Biodiversity Information Disclosure (CD), Investment Confidence (IC) and Investment Willingness (IW)

2.3. Investment Confidence (IC) and Investment Willingness (IW)

2.4. The Moderating Effect of Risk Aversion (QA)

2.5. The Moderating Effect of Climate Risk Awareness (CA)

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Scale Development

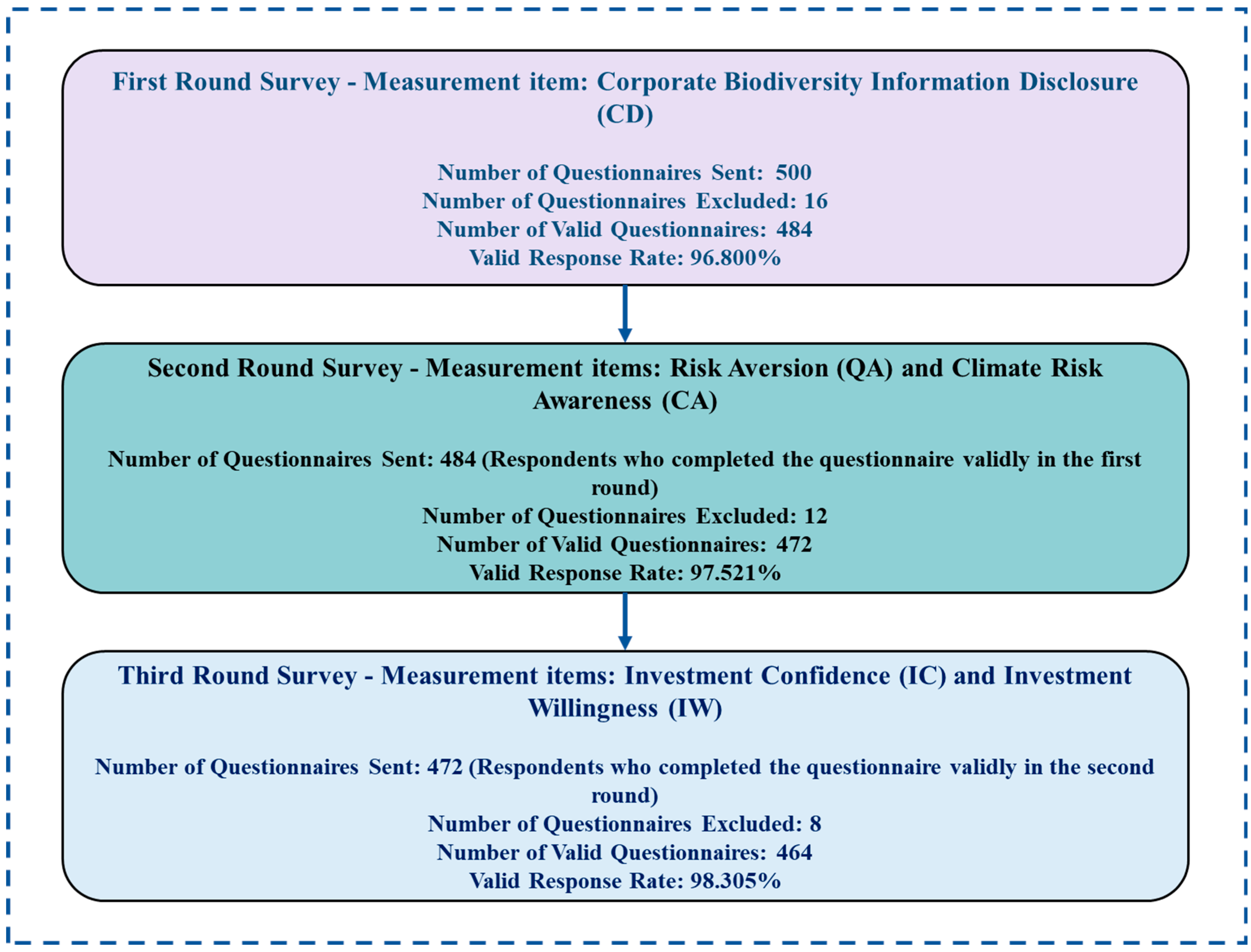

3.2. Respondent Recruitment and Data Collection

4. Empirical Analysis

4.1. Common Method Bias (CMB) Test

4.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis

4.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.4. Model Fit Test

4.5. Measurement Model Analysis

4.6. Structural Model Analysis

4.7. Moderation Effects Analysis

4.8. Model Robustness Test (Cross-Validation)

5. Summary and Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

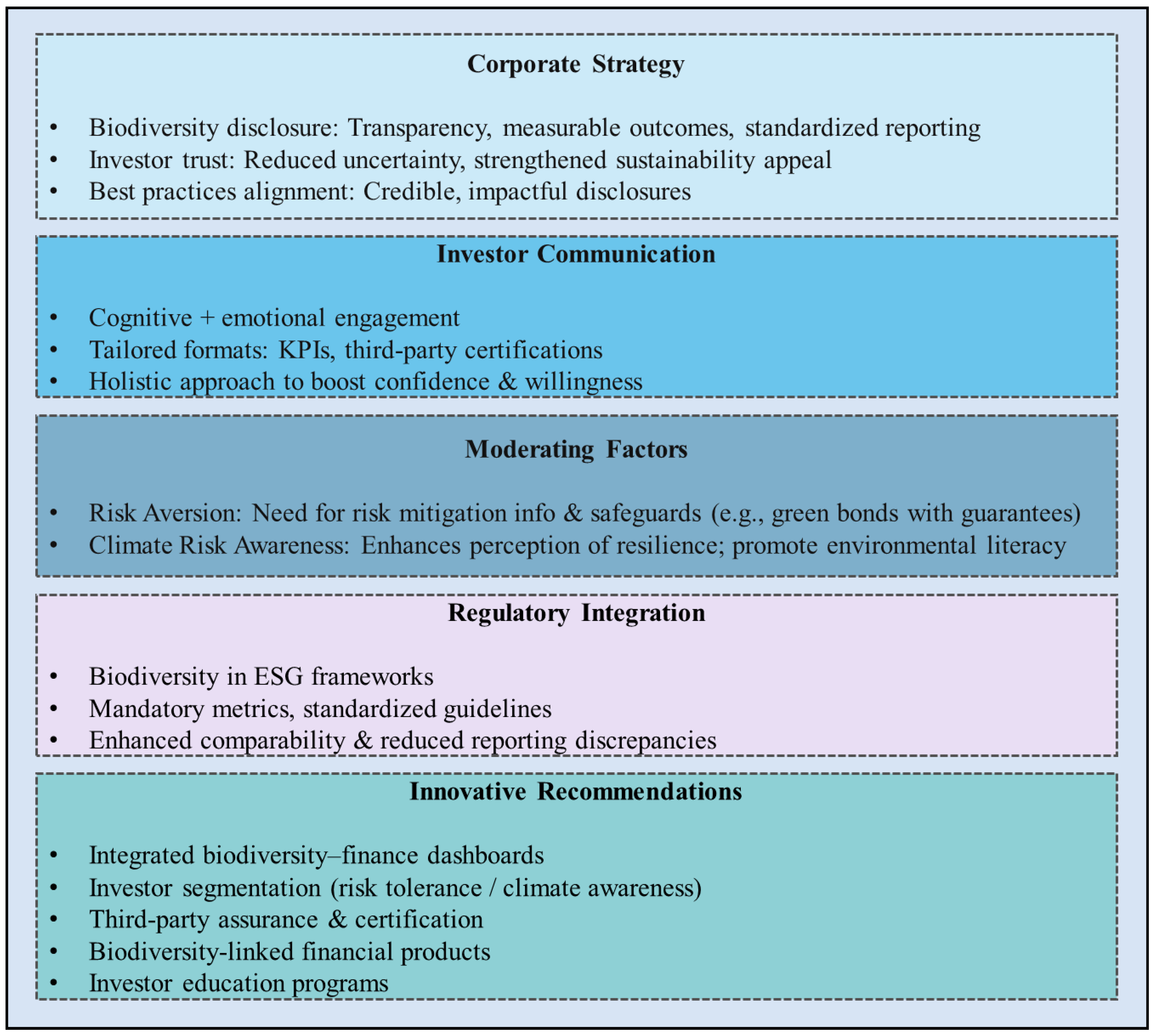

5.2. Practical and Managerial Implications

6. Research Limitations

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Survey Questionnaire

| Number | Question | Answer Option | ||||

| Q1 | What is your gender? | Female ❏ | Male ❏ | - | - | - |

| Q2 | Your marital status? | Singles and others ❏ | Married ❏ | - | - | - |

| Q3 | Where do you live? | Urban ❏ | Rural ❏ | - | - | - |

| Q4 | What is your exact location? | Beijing city ❏ | Shanghai city ❏ | Guangdong province ❏ | Anhui province ❏ | Jiangsu province ❏ |

| Q5 | How old are you? | 20–30 ❏ | 31–40 ❏ | 41–50 ❏ | 51–60 ❏ | >60 ❏ |

| Q6 | What is your level of education? | Junior college and below ❏ | Undergraduate ❏ | Postgraduate and above ❏ | - | - |

| Q7 | What is your average monthly income (CNY)? | <8000 ❏ | 8000–10,000 ❏ | 10,001–12,000 ❏ | >12,000 ❏ | - |

| Number | Dimension | Question | Score | ||||||

| Q1 | Corporate Biodiversity Information Disclosure (CD) | CD1: I believe the company provides detailed and specific disclosures regarding its biodiversity-related activities in its annual report or sustainability report. | 1❏ | 2❏ | 3❏ | 4❏ | 5❏ | 6❏ | 7❏ |

| Q2 | CD2: I feel that the biodiversity information disclosed by the company includes quantifiable data (such as impact measurement metrics, geographic locations, affected species, etc.). | 1❏ | 2❏ | 3❏ | 4❏ | 5❏ | 6❏ | 7❏ | |

| Q3 | CD3: I believe the company’s disclosures regarding biodiversity are transparent and can be verified by external stakeholders (for example, through references to third-party assessments, independent audits, or publicly available data). | 1❏ | 2❏ | 3❏ | 4❏ | 5❏ | 6❏ | 7❏ | |

| Q4 | Investment Confidence (IC) | IC1: Based on the biodiversity information disclosed by the company, I have confidence in its future environmental performance improvements. | 1❏ | 2❏ | 3❏ | 4❏ | 5❏ | 6❏ | 7❏ |

| Q5 | IC2: I believe the company’s disclosures regarding biodiversity management indicate that its long-term operational risks are manageable, thereby increasing my confidence in the safety of my investment. | 1❏ | 2❏ | 3❏ | 4❏ | 5❏ | 6❏ | 7❏ | |

| Q6 | IC3: After seeing the company’s disclosures on biodiversity, I am more confident that it can achieve stable green investment returns in the future. | 1❏ | 2❏ | 3❏ | 4❏ | 5❏ | 6❏ | 7❏ | |

| Q7 | Investment Willingness (IW) | IW1: If other conditions are the same, I would prefer to invest in companies that provide comprehensive disclosures of biodiversity information. | 1❏ | 2❏ | 3❏ | 4❏ | 5❏ | 6❏ | 7❏ |

| Q8 | IW2: Within my existing green investment portfolio, I am willing to increase the proportion of holdings in companies that have good disclosures related to biodiversity. | 1❏ | 2❏ | 3❏ | 4❏ | 5❏ | 6❏ | 7❏ | |

| Q9 | IW3: I am willing to make green investments in companies that actively disclose biodiversity information. | 1❏ | 2❏ | 3❏ | 4❏ | 5❏ | 6❏ | 7❏ | |

| Q10 | Risk Aversion (QA) | QA1: Compared to seeking potentially higher but uncertain returns, I prefer to choose investments with lower but more certain returns. | 1❏ | 2❏ | 3❏ | 4❏ | 5❏ | 6❏ | 7❏ |

| Q11 | QA2: I believe I am a risk-averse person. | 1❏ | 2❏ | 3❏ | 4❏ | 5❏ | 6❏ | 7❏ | |

| Q12 | QA3: When making investments, I dislike taking risks. | 1❏ | 2❏ | 3❏ | 4❏ | 5❏ | 6❏ | 7❏ | |

| Q13 | Climate Risk Awareness (CA) | CA1: I think that climate change will have profound effects on society, the economy, and human well-being. | 1❏ | 2❏ | 3❏ | 4❏ | 5❏ | 6❏ | 7❏ |

| Q14 | CA2: I am aware that climate change may exacerbate the scarcity of natural resources (such as water and land). | 1❏ | 2❏ | 3❏ | 4❏ | 5❏ | 6❏ | 7❏ | |

| Q15 | CA3: I have a certain understanding of the environmental risks posed by climate change (such as rising sea levels and biodiversity loss). | 1❏ | 2❏ | 3❏ | 4❏ | 5❏ | 6❏ | 7❏ | |

References

- Aggarwal, S., Lone, F. A., & Paliwal, M. (2025). Green bonds: A demographic study of Retail Investors in India. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 102, 101991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, R., García-Sánchez, I. M., Aibar-Guzmán, B., & Rehman, R. U. (2024). Is biodiversity disclosure emerging as a key topic on the agenda of institutional investors? Business Strategy and the Environment, 33(3), 2116–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsos, G. A., & Ljunggren, E. (2017). The role of gender in entrepreneur–investor relationships: A signaling theory approach. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 41(4), 567–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameli, N., Drummond, P., Bisaro, A., Grubb, M., & Chenet, H. (2020). Climate finance and disclosure for institutional investors: Why transparency is not enough. Climatic Change, 160(4), 565–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananda, S., Kumar, R. P., & Dalwai, T. (2024). Impact of financial literacy on savings behavior: The moderation role of risk aversion and financial confidence. Journal of Financial Services Marketing, 29(3), 843–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aren, S., & Nayman Hamamci, H. (2020). Relationship between risk aversion, risky investment intention, investment choices: Impact of personality traits and emotion. Kybernetes, 49(11), 2651–2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aren, S., & Nayman Hamamci, H. (2023). Evaluation of investment preference with phantasy, emotional intelligence, confidence, trust, financial literacy and risk preference. Kybernetes, 52(12), 6203–6231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aruga, K. (2025). Are retail investors willing to buy green bonds? A case for Japan. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, 15(2), 388–402. [Google Scholar]

- Aspara, J. (2013). The role of product and brand perceptions in stock investing: Effects on investment considerations, optimism and confidence. Journal of Behavioral Finance, 14(3), 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aumeboonsuke, V., & Caplanova, A. (2023). An analysis of impact of personality traits and mindfulness on risk aversion of individual investors. Current Psychology, 42(8), 6800–6817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16(1), 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldenius, T., & Meng, X. (2010). Signaling firm value to active investors. Review of Accounting Studies, 15(3), 584–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberis, N. C. (2013). Thirty years of prospect theory in economics: A review and assessment. Journal of economic perspectives, 27(1), 173–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassen, A., Buchholz, D., Lopatta, K., & Rudolf, A. R. (2025). Assessing biodiversity-related disclosure: Drivers, outcomes, and financial impacts. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 29(1), 311–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassen, A., Gödker, K., Lüdeke-Freund, F., & Oll, J. (2019). Climate information in retail investors’ decision-making: Evidence from a choice experiment. Organization & Environment, 32(1), 62–82. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler, P. M., & Bonett, D. G. (1980). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88(3), 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohnett, E., Coulibaly, A., Hulse, D., Hoctor, T., Ahmad, B., An, L., & Lewison, R. (2022). Corporate responsibility and biodiversity conservation: Challenges and opportunities for companies participating in China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Environmental Conservation, 49(1), 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castilla-Polo, F., García-Martínez, G., Guerrero-Baena, M. D., & Polo-Garrido, F. (2025). The cooperative ESG disclosure index: An empirical approach. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 27(8), 18699–18724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, R. H., Clark, E., Guo, X., & Wong, W. K. (2020). New development on the third-order stochastic dominance for risk-averse and risk-seeking investors with application in risk management. Risk Management, 22(2), 108–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 9(2), 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohn, R. A., Lewellen, W. G., Lease, R. C., & Schlarbaum, G. G. (1975). Individual investor risk aversion and investment portfolio composition. The Journal of Finance, 30(2), 605–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, J. (2020). Applied structural equation modeling using AMOS: Basic to advanced techniques. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Connelly, B. L., Certo, S. T., Ireland, R. D., & Reutzel, C. R. (2011). Signaling theory: A review and assessment. Journal of Management, 37(1), 39–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, B. L., Certo, S. T., Reutzel, C. R., DesJardine, M. R., & Zhou, Y. S. (2025). Signaling theory: State of the theory and its future. Journal of Management, 51(1), 24–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cudeck, R. (2000). Exploratory factor analysis. In Handbook of applied multivariate statistics and mathematical modeling (pp. 265–296). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cudeck, R., & Browne, M. W. (1983). Cross-validation of covariance structures. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 18(2), 147–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Gesso, C., & Lodhi, R. N. (2025). Theories underlying environmental, social and governance (ESG) disclosure: A systematic review of accounting studies. Journal of Accounting Literature, 47(2), 433–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, P., & Dutta, A. (2024). Does corporate environmental performance affect corporate biodiversity reporting decision? The Finnish evidence. Journal of Applied Accounting Research, 25(1), 24–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Khoury, R., Du, A. M., Nasrallah, N., Marashdeh, H., & Atayah, O. F. (2025). Towards sustainability: Examining financial, economic, and societal determinants of environmental degradation. Research in International Business and Finance, 73, 102557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, V., Jonäll, K., Paananen, M., Bebbington, J., & Michelon, G. (2024). Biodiversity reporting: Standardization, materiality, and assurance. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 68, 101435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eluyela, D. F., Pandey, R., Deegan, C., & Mansi, M. (2025). Biodiversity research from an accountability perspective: Current gaps and prospects for future research. Sustainable Development. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/sd.70259?af=R (accessed on 9 December 2025). [CrossRef]

- Essiz, O., Yurteri, S., Mandrik, C., & Senyuz, A. (2023). Exploring the value-action gap in green consumption: Roles of risk aversion, subjective knowledge, and gender differences. Journal of Global Marketing, 36(1), 67–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyraud, L., Clements, B., & Wane, A. (2013). Green investment: Trends and determinants. Energy Policy, 60, 852–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flammer, C., Giroux, T., & Heal, G. M. (2025). Biodiversity finance. Journal of Financial Economics, 164, 103987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, J., & Kara, S. M. (2010). Confidence mediates how investment knowledge influences investing self-efficacy. Journal of Economic Psychology, 31(3), 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of marketing research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garel, A., Romec, A., Sautner, Z., & Wagner, A. F. (2024). Do investors care about biodiversity? Review of Finance, 28(4), 1151–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gede Nyoman Yetna, I., Halim, R. E., & Kurniawan, H. T. (2022). The Roles of investment prospect, trust and confidence toward investors’ willingness to buy in market uncertainty. International Journal of Business, 27(4). Available online: https://scholar.ui.ac.id/en/publications/the-roles-of-investment-prospect-trust-and-confidence-toward-inve/ (accessed on 9 December 2025). [CrossRef]

- Hambali, A., & Adhariani, D. (2024). Corporate biodiversity disclosure: The role of institutional factors and corporate governance. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 31(6), 5260–5274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemdan, W., & Zhang, J. (2025). Investors’ intention toward green investment: An extension of the theory of planned behavior. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 20(9), 3744–3759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, A. O., & Post, T. (2016). How does investor confidence lead to trading? Linking investor return experiences, confidence, and investment beliefs. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance, 12, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunjra, A. I., & Rehman, Z. U. (2016). Factors affecting investment decision mediated by risk aversion: A case of Pakistani investors. International Journal of Economics and Empirical Research, 4(4), 169–181. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, M. A., Shaheen, W. A., Shabir, S., Ullah, U., Ionel-Alin, I., Mihut, M. I., Raposo, A., & Han, H. (2025). Towards a green economy: Investigating the impact of sustainable finance, green technologies, and environmental policies on environmental degradation. Journal of Environmental Management, 374, 124047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keck, F., Peller, T., Alther, R., Barouillet, C., Blackman, R., Capo, E., Chonova, T., Couton, M., Fehlinger, L., Kirschner, D., & Knüsel, M. (2025). The global human impact on biodiversity. Nature, 641, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keckel, L., Feuer, Y. S. L., & Sassen, R. (2025). Identifying motivations, measures and challenges to implement corporate biodiversity management and reporting: A systematic review across sectors and regions. Journal of Environmental Management, 389, 125987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, F., Su, C. Y., Weiwei, K., Voinea, C. L., & Srivastava, M. (2025). Financial mechanism for sustainability: The case of China’s green financial system and corporate green investment. China Finance Review International, 15(1), 93–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, H., & Upadhayaya, S. (2020). Does business confidence matter for investment? Empirical Economics, 59(4), 1633–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. A., Yau, J. T. H., Sarang, A. A. A., Gull, A. A., & Javed, M. (2025). Information asymmetry and investment efficiency: The role of blockholders. Journal of Applied Accounting Research, 26(1), 194–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komara, A., Ghozali, I., & Januarti, I. (2020, March). Examining the firm value based on signaling theory. In 1st international conference on accounting, management and entrepreneurship (ICAMER 2019) (pp. 1–4). Atlantis Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kurowski, Ł., Rutecka-Góra, J., & Smaga, P. (2025). Promoting environmentally and socially responsible investing: Interplay between climate and financial literacy. Climate Policy, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyaw, K., Olugbode, M., & Petracci, B. (2022). Stakeholder engagement: Investors’ environmental risk aversion and corporate earnings. Business Strategy and the Environment, 31(3), 1220–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T. M., Markowitz, E. M., Howe, P. D., Ko, C. Y., & Leiserowitz, A. A. (2015). Predictors of public climate change awareness and risk perception around the world. Nature Climate Change, 5(11), 1014–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y. J., Tung, C. M., & Lin, S. C. (2019). Attitudes to climate change, perceptions of disaster risk, and mitigation and adaptation behavior in Yunlin County, Taiwan. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 26(30), 30603–30613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, J. S. (1992). An introduction to prospect theory. Political Psychology, 13, 171–186. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X., Li, W., Xu, J., & Wang, L. (2025). Retail investor activism and corporate environmental investments: Evidence from green attention. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 20(10), 4078–4110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X., & Tian, Q. (2024). Public perception of climate risk, environmental image, and corporate green investment. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 114(6), 1137–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B., & Xie, Y. (2025). How does digital finance drive energy transition? A green investment-based perspective. Financial Innovation, 11(1), 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, T. D. (1997). Mean and covariance structures (MACS) analyses of cross-cultural data: Practical and theoretical issues. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 32(1), 53–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizarazo, S. V. (2013). Default risk and risk averse international investors. Journal of International Economics, 89(2), 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L., & Tang, Q. (2021). Corporate governance and carbon performance: Role of carbon strategy and awareness of climate risk. Accounting & Finance, 61(2), 2891–2934. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, H., Ning, W., Wang, J., & Wang, S. (2025). The impact of environmental pollution liability insurance on firms’ Green innovations: Evidence from China. Applied Economics Letters, 32(13), 1876–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, L., Elnahass, M., Xiang, E., Hawkins, F., Siikamaki, J., Hillis, L., Barrie, S., & McGowan, P. J. (2024). Corporate disclosures need a biodiversity outcome focus and regulatory backing to deliver global conservation goals. Conservation Letters, 17(4), e13024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N. K., Lopes, E., & Veiga, R. T. (2014). Structural equation modeling with Lisrel: An initial vision. Brazilian Journal of Marketing, 13(2). [Google Scholar]

- Meckling, W. H., & Jensen, M. C. (1976). Theory of the firm. Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure, 3(4), 305–360. [Google Scholar]

- Mei, K., & Zhang, Z. (2025). Environmental regulation, green investment and corporate green governance: Evidence from China’s new environmental protection law. Finance Research Letters, 76, 106979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirón Sanguino, Á. S., Muñoz-Muñoz, E., Crespo-Cebada, E., & Díaz-Caro, C. (2025). Willingness to pay for sustainable investment attributes: A mixed logit analysis of SDG 11. Mathematics, 13(16), 2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A. K., Bansal, R., Maurya, P. K., Ansari, Y., & Gupta, N. (2025). Effect of service quality on intention to invest in mutual funds: Attitude as mediator and awareness as moderator. Journal of Advances in Management Research. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moses, A., & Yahaya, A. (2024). Do boards care about biodiversity-related information disclosure. Journal of Corporate Governance and Social Responsibility, 10(21), 112–146. [Google Scholar]

- Mossholder, K. W., Bennett, N., Kemery, E. R., & Wesolowski, M. A. (1998). Relationships between bases of power and work reactions: The mediational role of procedural justice. Journal of Management, 24(4), 533–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, H., & Ali, S. (2025). The interplay of board gender diversity, debt financing, and sustainable investment: Evidence from Europe. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, 15(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Nafisa, R., Alam, M. A., & Qian, A. (2023). Corporate ESG issues and retail investors’ investment decision: A moral awareness perspective. International Journal of Research in Business and Social Science, 12(9), 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özçelik, M., & Kurt, G. (2024). The measurement of fraud perception of investors and the mediating effect of risk aversion: The case of crypto assets. International Journal of Accounting & Information Management. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar]

- Pervez, Z., Shah, T. A., & Khattak, A. (2025). The Influence of Anchoring Bias in Stock Exchange Investments: Exploring Risk Perception and Information Asymmetry. Journal of Business and Management Research, 4(1), 476–495. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pokharel, P. R. (2025). Unpacking the role of biodiversity impact reduction in ESG performance. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 32, 8094–8110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raubenheimer, J. (2004). An item selection procedure to maximize scale reliability and validity. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 30(4), 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlan, M. K. (2021). Climate risk is investment risk. Multinational Corporations (FALL 2020), 35, 18–22+27. [Google Scholar]

- Senanayake, M., Harymawan, I., Dorfleitner, G., Lee, S., Rhee, J. H., & Ok, Y. S. (2024). Toward more nature-positive outcomes: A review of corporate disclosure and decision making on biodiversity. Sustainability, 16(18), 8110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahwan, Y. (2025). Corporate social responsibility, corporate governance, and asymmetric information: Evidence from Jordan. Business Strategy & Development, 8(2), e70138. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, S. P. (2005). Agency theory. Annual Review of Sociology, 31(1), 263–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M., Nanda, S., & Gupta, S. (2024). A systematic review of investment confidence, risk appetite and dependence status of women. International Journal of System Assurance Engineering and Management, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair-Desgagne, B., & Gozlan, E. (2003). A theory of environmental risk disclosure. Journal of environmental Economics and Management, 45(2), 377–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X., & Yang, L. (2025). Driving climate risk awareness: The impact of the big three. Applied Economics, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, V. D., & Rojjanasrirat, W. (2011). Translation, adaptation and validation of instruments or scales for use in cross-cultural health care research: A clear and user-friendly guideline. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 17(2), 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, Y., & Lee, C. C. (2025). Green finance, environmental quality and technological innovation in China. International Journal of Finance & Economics, 30(1), 405–425. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, Z. (2025). Corporate biodiversity information disclosure in focus: The triad of institutional pressures, ecosystem service and green supply chain management in China’s corporate landscape. Biological Conservation, 311, 111453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanasegaran, G. (2009). Reliability and validity issues in research. Integration & Dissemination, 4, 35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y., & Chen, H. (2025). Eco-innovation under pressure: How biodiversity risks shape corporate sustainability strategies. Finance Research Letters, 73, 106615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todaro, N. M., Testa, F., Daddi, T., & Iraldo, F. (2021). The influence of managers’ awareness of climate change, perceived climate risk exposure and risk tolerance on the adoption of corporate responses to climate change. Business Strategy and the Environment, 30(2), 1232–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toukabri, M., & Toukabri, M. (2025). Evolution of corporate accountability for biodiversity reporting. Do stakeholder capitalism and institutional context matter? A bibliometric analysis. Business Strategy & Development, 8(2), e70095. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker, L. R., & MacCallum, R. C. (1997). Exploratory factor analysis [Unpublished Manuscript] (pp. 1–459). Ohio State University, Columbus. [Google Scholar]

- Velte, P. (2023). Sustainable institutional investors and corporate biodiversity disclosure: Does sustainable board governance matter? Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 30(6), 3063–3074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasiuzzaman, S., & Hj Ahmad, A. M. S. L. P. (2025). Perception towards government advisory, perceived risk and willingness to invest in cryptocurrency. Journal of Economics and Business, 133, 106208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winingshe, W. (2025). The effect of information asymmetry, systematic risk and investment opportunity (IOS) on profit quality in food & beverage. Journal of Applied Accounting and Sustainable Finance, 1(1), 42–53. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y., Sun, H., Zhang, L., & Cui, C. (2025). Green investment and quality of economic development: Evidence from China. International Review of Financial Analysis, 103, 104147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, M., Fang, W., Liu, Y., Feng, T., & Bhattacharya, A. (2025). Unveiling the green veil: Customer green relational capital and tone ambiguity in supplier environmental disclosure. Journal of Business Research, 191, 115258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahaya, O. A. (2025). The influence of environmental disclosure on corporate information asymmetry. Available at SSRN 5171725. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5171725 (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Yao, Z., & Rabbani, A. G. (2021). Association between investment risk tolerance and portfolio risk: The role of confidence level. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance, 30, 100482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, B., & Yuan, J. (2008). Firm value, managerial confidence, and investments: The case of China. Journal of Leadership Studies, 2(3), 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, E. P. Y., Guo, C. Q., & Luu, B. V. (2018). Environmental, social and governance transparency and firm value. Business Strategy and the Environment, 27(7), 987–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaiţ, A., & Bertea, P. E. (2011). Methods for testing discriminant validity. Management & Marketing Journal, 9(2), 217–224. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H., He, F., Wei, T., Zhu, Y., Zhang, Y., & Yan, L. (2025). Impact of online opinions: Do retail investor concerns inhibit corporate green investment intentions? China Finance Review International, 15(2), 305–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Measurement Items | References |

|---|---|---|

| Corporate Biodiversity Information Disclosure (CD) | CD1: I believe the company provides detailed and specific disclosures regarding its biodiversity-related activities in its annual report or sustainability report. | Moses and Yahaya (2024); Tao (2025) |

| CD2: I feel that the biodiversity information disclosed by the company includes quantifiable data (such as impact measurement metrics, geographic locations, affected species, etc.). | ||

| CD3: I believe the company’s disclosures regarding biodiversity are transparent and can be verified by external stakeholders (for example, through references to third-party assessments, independent audits, or publicly available data). | ||

| Investment Confidence (IC) | IC1: Based on the biodiversity information disclosed by the company, I have confidence in its future environmental performance improvements. | Zhang et al. (2025); Mishra et al. (2025) |

| IC2: I believe the company’s disclosures regarding biodiversity management indicate that its long-term operational risks are manageable, thereby increasing my confidence in the safety of my investment. | ||

| IC3: After seeing the company’s disclosures on biodiversity, I am more confident that it can achieve stable green investment returns in the future. | ||

| Investment Willingness (IW) | IW1: If other conditions are the same, I would prefer to invest in companies that provide comprehensive disclosures of biodiversity information. | Mishra et al. (2025); Hemdan and Zhang (2025) |

| IW2: Within my existing green investment portfolio, I am willing to increase the proportion of holdings in companies that have good disclosures related to biodiversity. | ||

| IW3: I am willing to make green investments in companies that actively disclose biodiversity information. | ||

| Risk Aversion (QA) | QA1: Compared to seeking potentially higher but uncertain returns, I prefer to choose investments with lower but more certain returns. | Hunjra and Rehman (2016); Aumeboonsuke and Caplanova (2023) |

| QA2: I believe I am a risk-averse person. | ||

| QA3: When making investments, I dislike taking risks. | ||

| Climate Risk Awareness (CA) | CA1: I think that climate change will have profound effects on society, the economy, and human well-being. | Y. J. Lee et al. (2019); Todaro et al. (2021) |

| CA2: I am aware that climate change may exacerbate the scarcity of natural resources (such as water and land). | ||

| CA3: I have a certain understanding of the environmental risks posed by climate change (such as rising sea levels and biodiversity loss). |

| Categories | Options | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 232 | 50.000% |

| Male | 232 | 50.000% | |

| Marriage | Singles and others | 221 | 47.629% |

| Married | 243 | 52.371% | |

| Area | Urban | 260 | 56.034% |

| Rural | 204 | 43.966% | |

| Location | Beijing city | 95 | 20.474% |

| Shanghai city | 93 | 20.043% | |

| Guangdong province | 90 | 19.397% | |

| Anhui province | 91 | 19.612% | |

| Jiangsu province | 95 | 20.474% | |

| Age | 20–30 | 120 | 25.862% |

| 31–40 | 99 | 21.336% | |

| 41–50 | 94 | 20.259% | |

| 51–60 | 85 | 18.319% | |

| >60 | 66 | 14.224% | |

| Education level | Junior college and below | 157 | 33.836% |

| Undergraduate | 179 | 38.578% | |

| Postgraduate and above | 128 | 27.586% | |

| Average monthly income (CNY) | <8000 | 117 | 25.216% |

| 8000–10,000 | 120 | 25.862% | |

| 10,001–12,000 | 135 | 29.095% | |

| >12,000 | 92 | 19.828% |

| Model | χ2 | Df | ∆χ2 | ∆Df | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-factor | 3654.848 | 90 | 3556.615 | 10 | 0.000 |

| Multi-factor | 98.233 | 80 |

| Variables | Items | Loading | Eigenvalues | Explain the Variation Amount/% | Explain the Cumulative Variation Amount/% | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Investment Confidence (IC) | IC1 | 0.903 | 2.695 | 17.967 | 17.967 | 0.940 |

| IC2 | 0.897 | |||||

| IC3 | 0.922 | |||||

| Investment Willingness (IW) | IW1 | 0.881 | 2.688 | 17.918 | 35.885 | 0.950 |

| IW2 | 0.902 | |||||

| IW3 | 0.919 | |||||

| Risk Aversion (QA) | QA1 | 0.928 | 2.612 | 17.411 | 53.296 | 0.922 |

| QA2 | 0.932 | |||||

| QA3 | 0.919 | |||||

| Climate Risk Awareness (CA) | CA1 | 0.917 | 2.592 | 17.277 | 70.573 | 0.915 |

| CA2 | 0.928 | |||||

| CA3 | 0.912 | |||||

| Corporate Biodiversity Information Disclosure (CD) | CD1 | 0.826 | 2.320 | 15.468 | 86.042 | 0.845 |

| CD2 | 0.873 | |||||

| CD3 | 0.877 |

| Fit Indicators | χ2 | df | χ2/df | RMSEA | CFI | IFI | TLI | GFI | AGFI | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Five-factor model | 98.233 | 80 | 1.228 | 0.022 | 0.997 | 0.997 | 0.996 | 0.973 | 0.959 | 0.020 |

| Four-factor model | 701.749 | 84 | 8.354 | 0.126 | 0.889 | 0.889 | 0.861 | 0.828 | 0.755 | 0.105 |

| Three-factor model | 1668.922 | 87 | 19.183 | 0.198 | 0.715 | 0.716 | 0.656 | 0.681 | 0.561 | 0.133 |

| Two-factor model | 2701.154 | 89 | 30.350 | 0.252 | 0.529 | 0.530 | 0.444 | 0.579 | 0.432 | 0.181 |

| One-factor model | 3654.848 | 90 | 40.609 | 0.292 | 0.357 | 0.359 | 0.250 | 0.507 | 0.342 | 0.215 |

| Variables | Items | Unstd. | S.E. | Z | p | Std. | Cronbach’s α | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corporate Biodiversity Information Disclosure (CD) | CD1 | 1.000 | 0.687 | 0.845 | 0.654 | 0.849 | |||

| CD2 | 1.377 | 0.089 | 15.547 | *** | 0.860 | ||||

| CD3 | 1.471 | 0.095 | 15.558 | *** | 0.866 | ||||

| Investment Confidence (IC) | IC1 | 1.000 | 0.912 | 0.940 | 0.842 | 0.941 | |||

| IC2 | 1.105 | 0.035 | 31.414 | *** | 0.910 | ||||

| IC3 | 1.073 | 0.033 | 32.967 | *** | 0.930 | ||||

| Investment Willingness (IW) | IW1 | 1.000 | 0.919 | 0.950 | 0.865 | 0.951 | |||

| IW2 | 1.004 | 0.028 | 35.896 | *** | 0.940 | ||||

| IW3 | 0.933 | 0.027 | 34.944 | *** | 0.931 | ||||

| Risk Aversion (QA) | QA1 | 1.000 | 0.902 | 0.922 | 0.801 | 0.923 | |||

| QA2 | 1.049 | 0.037 | 28.528 | *** | 0.912 | ||||

| QA3 | 1.081 | 0.041 | 26.463 | *** | 0.870 | ||||

| Climate Risk Awareness (CA) | CA1 | 1.000 | 0.888 | 0.915 | 0.789 | 0.918 | |||

| CA2 | 1.194 | 0.045 | 26.658 | *** | 0.900 | ||||

| CA3 | 1.180 | 0.046 | 25.674 | *** | 0.876 |

| CA | QA | IW | IC | CD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CA | 0.888 | ||||

| QA | −0.013 | 0.895 | |||

| IW | 0.257 | −0.170 | 0.930 | ||

| IC | 0.159 | −0.162 | 0.517 | 0.917 | |

| CD | −0.027 | 0.052 | 0.338 | 0.272 | 0.809 |

| Hypothesis | Path | Unstd. (β) | S.E. | Z | p-Value | Std. | Test Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | CD → IC | 0.414 | 0.079 | 5.241 | *** | 0.272 | Validated |

| H2 | CD → IW | 0.334 | 0.073 | 4.552 | *** | 0.213 | Validated |

| H3 | IC → IW | 0.472 | 0.047 | 10.117 | *** | 0.459 | Validated |

| Dependent Variable | Independent Variable | Unstd. | SE | T | p | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The moderation effect of QA | |||||||

| IC | CD | 0.307 | 0.053 | 5.809 | 0.000 | 0.203 | 0.410 |

| QA | −0.156 | 0.045 | −3.455 | 0.001 | −0.244 | −0.067 | |

| CD × QA | −0.140 | 0.041 | −3.386 | 0.001 | −0.222 | −0.059 | |

| IW | CD | 0.348 | 0.049 | 7.109 | 0.000 | 0.252 | 0.445 |

| QA | −0.164 | 0.042 | −3.912 | 0.000 | −0.246 | −0.081 | |

| CD × QA | −0.122 | 0.039 | −3.158 | 0.002 | −0.197 | −0.046 | |

| The moderation effect of CA | |||||||

| IC | CD | 0.312 | 0.051 | 6.083 | 0.000 | 0.211 | 0.413 |

| CA | 0.145 | 0.043 | 3.346 | 0.001 | 0.060 | 0.230 | |

| CD × CA | 0.256 | 0.042 | 6.137 | 0.000 | 0.174 | 0.338 | |

| IW | CD | 0.357 | 0.046 | 7.717 | 0.000 | 0.266 | 0.448 |

| CA | 0.224 | 0.039 | 5.735 | 0.000 | 0.147 | 0.300 | |

| CD × CA | 0.263 | 0.038 | 7.006 | 0.000 | 0.189 | 0.337 | |

| Model | ΔDF | ΔCMIN | p | ΔNFI | ΔIFI | ΔRFI | ΔTLI | ΔCFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement weights | 6.000 | 3.052 | 0.802 | 0.001 | 0.001 | −0.002 | −0.002 | 0.000 |

| Structural weights | 3.000 | 10.118 | 0.018 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| Structural covariances | 1.000 | 0.046 | 0.829 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | −0.001 | −0.001 |

| Structural residuals | 2.000 | 1.886 | 0.390 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Measurement residuals | 9.000 | 5.217 | 0.815 | 0.001 | 0.002 | −0.002 | −0.002 | −0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tao, Z. The Impact of Corporate Biodiversity Information Disclosure on Green Investment Confidence and Willingness of Retail Investors in China: The Moderating Roles of Risk Aversion and Climate Risk Awareness. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 715. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18120715

Tao Z. The Impact of Corporate Biodiversity Information Disclosure on Green Investment Confidence and Willingness of Retail Investors in China: The Moderating Roles of Risk Aversion and Climate Risk Awareness. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(12):715. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18120715

Chicago/Turabian StyleTao, Zhibin. 2025. "The Impact of Corporate Biodiversity Information Disclosure on Green Investment Confidence and Willingness of Retail Investors in China: The Moderating Roles of Risk Aversion and Climate Risk Awareness" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 12: 715. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18120715

APA StyleTao, Z. (2025). The Impact of Corporate Biodiversity Information Disclosure on Green Investment Confidence and Willingness of Retail Investors in China: The Moderating Roles of Risk Aversion and Climate Risk Awareness. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(12), 715. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18120715