False Stability? How Greenwashing Shapes Firm Risk in the Short and Long Run

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Greenwashing in Corporate Practice

2.2. Financial and Market Implications of Greenwashing

2.3. ESG, Carbon Emissions, and Greenwashing

2.4. Firm Risk Measurement and Its Relevance for Greenwashing

2.5. Greenwashing and Firm Risk in the Australian Context

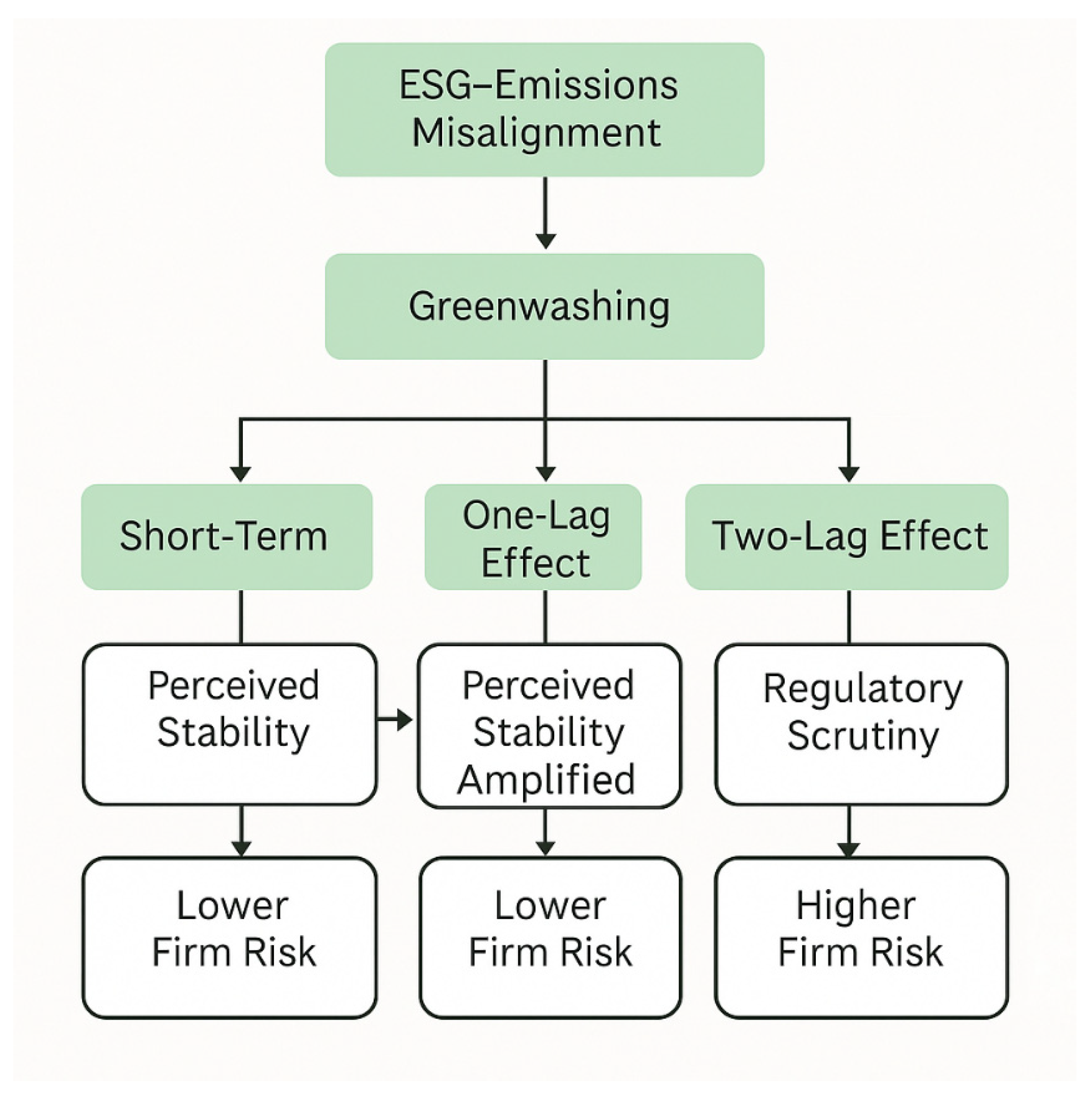

3. Theoretical Framework and Hypothesis

4. Research Design

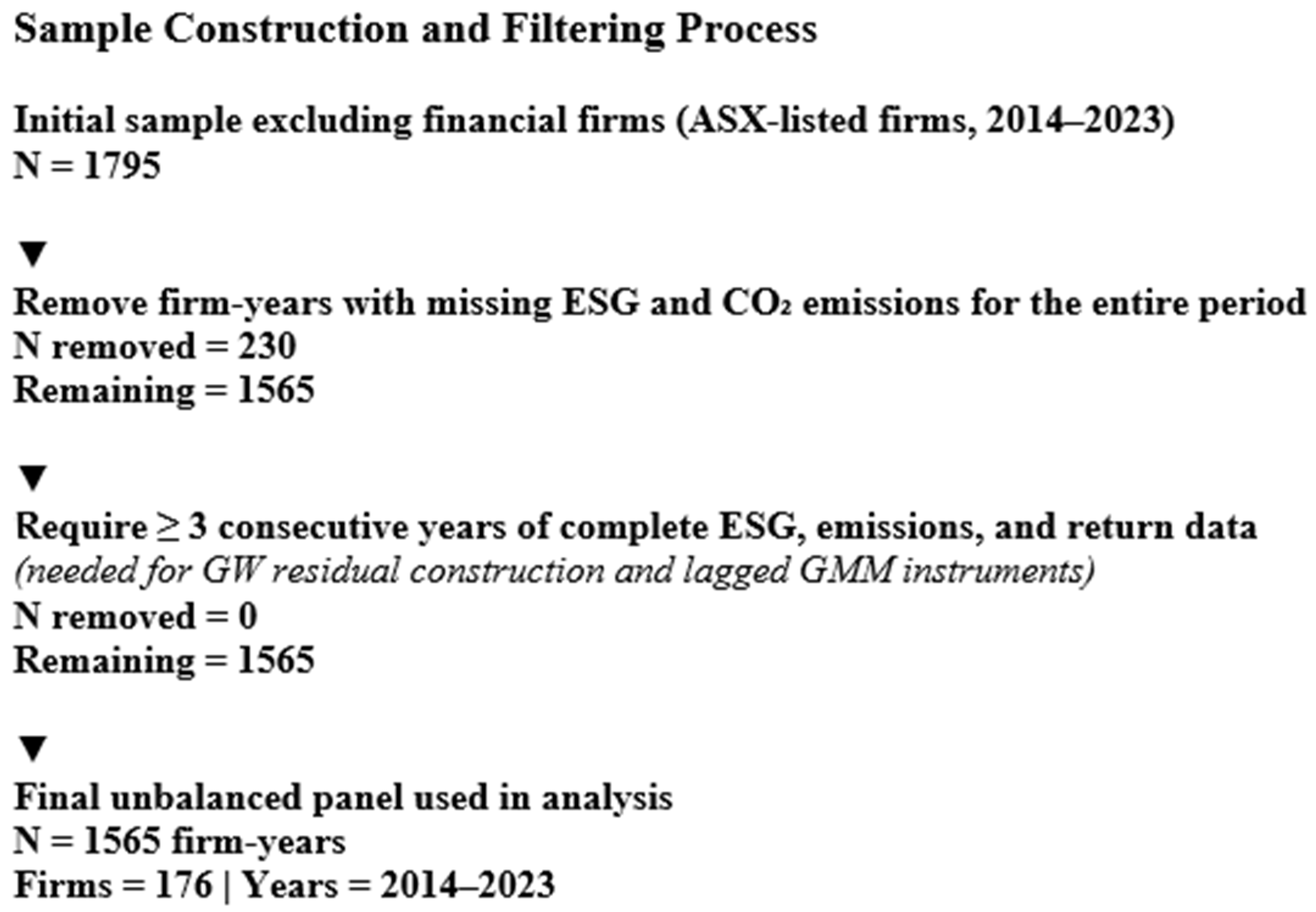

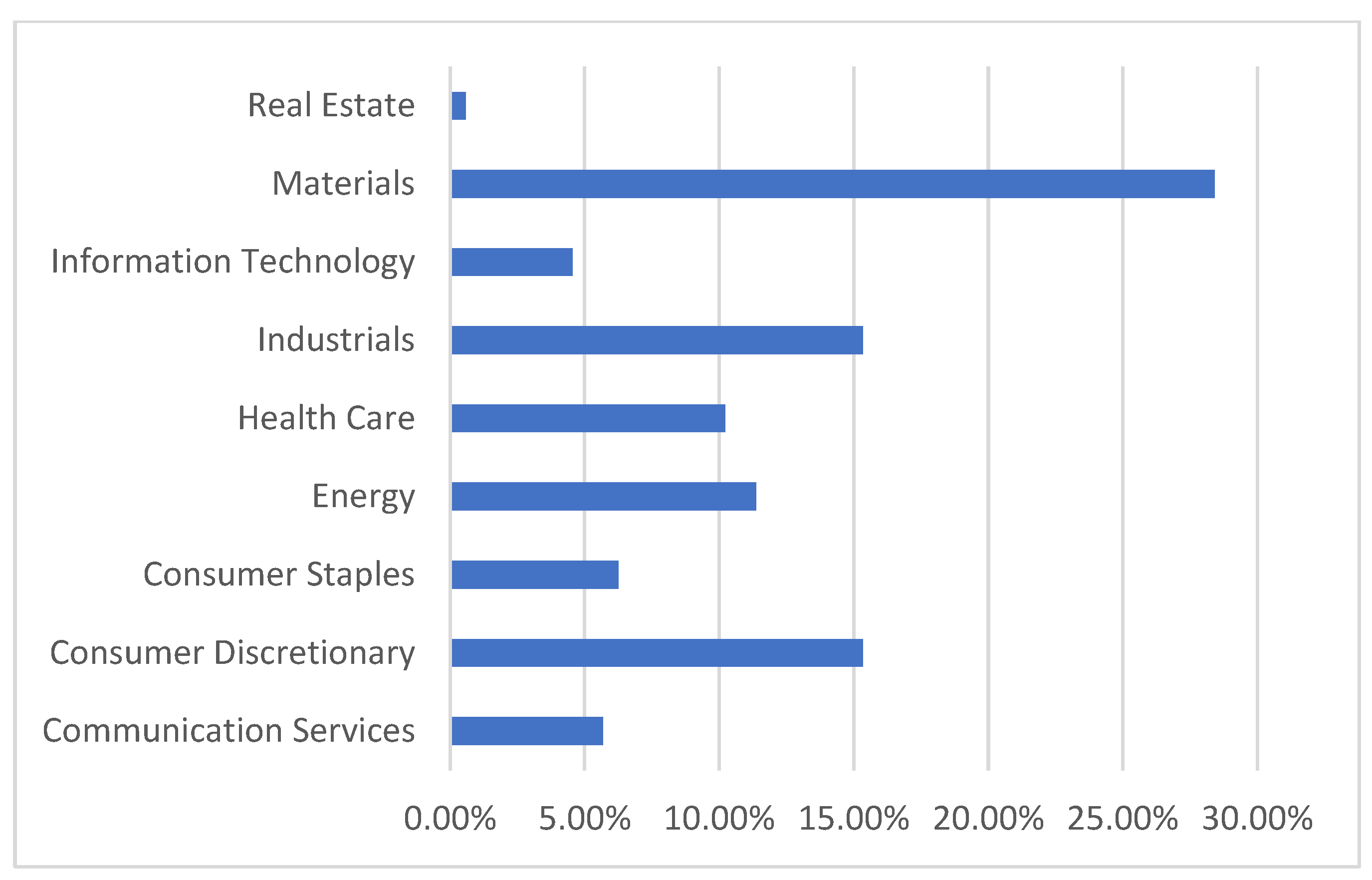

4.1. Data and Sample

- ESG Scores: LSEG provides standardized ESG scores ranging from 0 to 100, aggregated across environmental, social, and governance pillars.

- Carbon Emissions: LSEG reports firms’ Scope 1 and Scope 2 CO2 emissions (metric tons), which represent operational and energy-related emissions.

- Firm-Level Risk: Realized stock return volatility (RV) is calculated from daily price data sourced from LSEG Eikon.

- Controls: Key firm-level controls include size, profitability (ROA), leverage, and book-to-market ratio.

4.2. Variable Measurement

4.3. Greenwashing Proxy Construction

- ESGi,t = reported ESG score;

- CO2i,t = Scope 1 and 2 emissions;

- ϵi,t = residual = GW;

- Positive residuals (ϵ > 0) → ESG score exceeds what emissions justify → potential greenwashing;

- Negative residuals (ϵ < 0) → ESG scores align with or understate emissions performance → less likelihood of greenwashing.

4.4. Empirical Model

5. Empirical Analysis

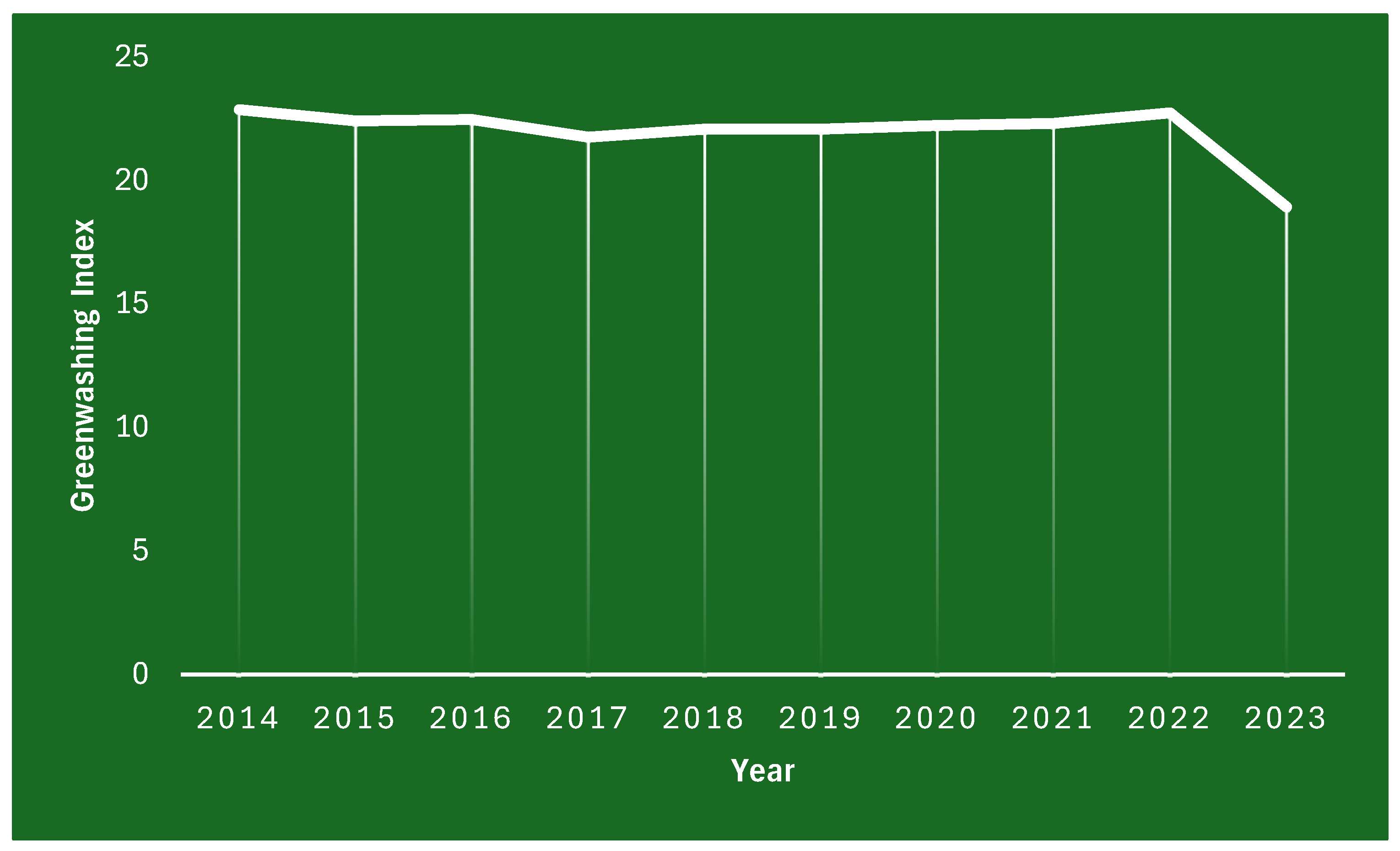

5.1. Descriptive Statistics, Graphical Analysis, and Correlation

- 2014–2017: Slight decline in GW, reflecting increasing awareness of sustainability disclosures.

- 2018–2022: Plateau in GW scores around 22–23, suggesting firms maintained consistent ESG signalling without substantial improvements in emissions alignment.

- 2023: Marked reduction, potentially attributable to ASIC’s anti-greenwashing enforcement measures, tighter climate-risk reporting regulations, and investor scrutiny.

5.2. Regression Analysis

- In the short run, greenwashing lowers perceived firm risk.

- With a one-period lag, the effect peaks, reflecting delayed investor reactions.

- Beyond this horizon, however, the benefits dissipate, consistent with increased transparency and stronger anti-greenwashing enforcement in Australia.

5.3. Robustness Check: Using the Environmental (E) Pillar

- H1 (Short-Term Effect)The contemporaneous coefficient for GW.EPillar is negative and highly significant (β = −0.003334, p < 0.01), suggesting that firms engaging in greater environmental greenwashing experience lower perceived risk in the short term. This finding aligns with H1, indicating that overstated environmental credentials enhance legitimacy and temporarily signal stability to investors.

- One-Lag EffectWhen introducing a one-period lag (β = −0.003464, p < 0.05), the risk-reducing effect strengthens slightly compared to the contemporaneous model. This result likely reflects reporting delays in ESG and emissions data, i.e., investors react to greenwashing signals after disclosures are made public, amplifying the short-term perception of stability. The AR (2) statistic (p = 0.25) supports model validity, and the Hansen J-statistic (p = 0.05) suggests borderline but acceptable instrument strength.

- H2 (Two-Lag Effect)In contrast, the two-lag model reveals that the impact of greenwashing fades over time (β = −0.002649, p > 0.10), becoming statistically insignificant. This supports H2, demonstrating that as transparency improves and regulatory scrutiny intensifies, markets adjust their risk assessment and greenwashing no longer provides protective reputational benefits. However, the Hansen J-statistic (p = 0.01) indicates potential over-identification concerns, suggesting results from this specification should be interpreted cautiously.

- Additional InsightsInterestingly, cash holdings become significant in the one-lag model (p < 0.05) and remain positive in the two-lag model, implying that liquidity may interact with overstated environmental reporting to influence volatility dynamics in subsequent periods. Other control variables, including ROA, leverage, and BM, largely mirror the patterns seen in earlier models.

5.4. Robustness Check: Impact of COVID-19

- H1 (Short-Term Effect)After removing 2020–2021, the contemporaneous greenwashing coefficient becomes larger in magnitude and remains statistically significant (β = −0.01047, p < 0.05). This effect is almost double the pre-exclusion coefficient (−0.0059) reported in Table 5, indicating that outside of the extreme uncertainty of COVID-19, greenwashing reduces perceived volatility even more strongly. This supports H1 and suggests that during normal periods, overstated ESG claims are more effective at signalling stability and legitimacy to markets. However, the Hansen J-statistic (p = 0.03) indicates partial model validity, meaning instruments may be slightly weak when COVID years are removed, which is common when the sample size drops.

- One-Lag EffectThe lagged effect remains negative and statistically significant (β = −0.01093, p < 0.05). This shows that investors continue reacting to greenwashing disclosures with a one-period delay, consistent with the information-processing lag in ESG reporting. Hansen test (p = 0.02) signals partial model validity, meaning the instruments are not strong enough once COVID volatility is removed.

- H2 (Two-Lag Effect)In contrast to our earlier results, the two-lag effect is now stronger and statistically significant (β = −0.01447, p < 0.05). This is the opposite of the pre-exclusion pattern. Instead of fading out, the risk-reducing effect of greenwashing persists for two periods when the COVID-19 years are removed. This suggests that during “normal” economic environments:

- ➢

- Greenwashing has longer-lasting reputational effects;

- ➢

- Markets are slower to adjust or uncover exaggerations;

- ➢

- Transparency and regulatory detection mechanisms operate more gradually.

6. Discussion

6.1. Substantive Interpretation

6.2. Robustness and Measurement Validity

6.3. Mechanisms and the Australian Setting

- Reputational Buffer: Firms with strong ESG narratives project resilience and sustainability leadership, attracting investor trust and lowering perceived tail risk in the short term.

- Information Frictions: ESG and emissions data are often reported with lags, delaying the market’s ability to detect inconsistencies between claims and reality.

- Institutional Learning: Over time, regulatory interventions, improved disclosure frameworks, and enhanced investor analytics reduce the scope for misrepresentation, diminishing greenwashing’s impact on perceived risk.

6.4. Implications

6.5. Limitations and Avenues for Further Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alfeus, M., Harvey, J., & Maphatsoe, P. (2024). Improving realised volatility forecast for emerging markets. Journal of Economics and Finance, 49, 299–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, A., Hodrick, R. J., Xing, Y., & Zhang, X. (2006). The Cross-Section of Volatility and Expected Returns. The Journal of Finance, 61(1), 259–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadichal, S., Raj, P. M., & Padashetty, S. (2025). Green versus greenwashing: How consumers differentiate authentic green marketing from deceptive practices. Studies in Systems, Decision and Control, 237, 145–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., Hong, H., & Stein, J. C. (2001). Forecasting crashes: Trading volume, past returns, and conditional skewness in stock prices. Journal of Financial Economics, 61(3), 345–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, C. H., Laine, M., Roberts, R. W., & Rodrigue, M. (2015). Organized hypocrisy, organizational façades, and sustainability reporting. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 40(1), 78–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J. W., Hyun, S., & Park, J. H. (2023). Exploring the impact of information environment on ESG disclosure behavior: Evidence from national pensions and foreign investors. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corporate governance principles and recommendations (3rd ed.). (2014). Available online: https://www.asx.com.au/content/dam/asx/about/corporate-governance-council/draft-cgc-3rd-edition.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelhardt, N., Ekkenga, J., & Posch, P. (2021). ESG ratings and stock performance during the COVID-19 crisis. Sustainability, 13(13), 7133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engle, R. F., Hansen, M. K., Karagozoglu, A. K., & Lunde, A. (2020). News and idiosyncratic volatility: The public information processing hypothesis. Journal of Financial Econometrics, 19(1), 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J., Imerman, M. B., & Dai, W. (2016). What does the volatility risk premium say about liquidity provision and demand for hedging tail risk? Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, 34(4), 519–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finpublica. (2014). Australia ESG regulation. Finpublica. Available online: https://www.finpublica.org/australia-esg-regulation (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Freeman, R. E., & McVea, J. (2001). A stakeholder approach to strategic management. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghitti, M., Gianfrate, G., & Palma, L. (2023). The agency of greenwashing. Journal of Management and Governance, 28, 905–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, A., Sands, J., & Shams, S. (2023). Corporates’ sustainability disclosures impact on cost of capital and idiosyncratic risk. Meditari Accountancy Research, 31(4), 861–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorovaia, N., & Makrominas, M. (2024). Identifying greenwashing in corporate-social responsibility reports using natural-language processing. European Financial Management, 31(1), 427–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, R. P. (2024). How greenwashing affects firm risk: An international perspective. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(11), 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, A., Hasan, M. M., & Jiang, H. (2017). Stock price crash risk: Review of the empirical literature. Accounting & Finance, 58(S1), 211–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q., Marshall, B. R., Nguyen, J. H., Nguyen, N. H., Qiu, B., & Visaltanachoti, N. (2024). Greenwashing: Measurement and implications. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutton, A. P., Marcus, A. J., & Tehranian, H. (2009). Opaque financial reports, R2, and crash risk. Journal of Financial Economics, 94(1), 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K., & Rubin, P. H. (2001). Effects of harmful environmental events on reputations of firms (pp. 161–182). Emerald (MCB up) EBooks. Emerald Group Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.-H., & Lyon, T. P. (2015). Greenwash vs. brownwash: Exaggeration and undue modesty in corporate sustainability disclosure. Organization Science, 26(3), 705–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-B., & Zhang, L. (2014). Financial reporting opacity and expected crash risk: Evidence from implied volatility smirks. Contemporary Accounting Research, 31(3), 851–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KPMG. (2024). The challenge of greenwashing: An international regulatory overview. Available online: https://assets.kpmg.com/content/dam/kpmg/cy/pdf/2024/the-challenge-of-greenwashing-report.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Liu, D., Gu, K., & Hu, W. (2023). ESG performance and stock idiosyncratic volatility. Finance Research Letters, 58, 104393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G., Hao, Q., Shi, Y., Zhang, Y., & Wu, F. (2024). Does ESG report greenwashing increase stock price crash risk? China Journal of Accounting Studies, 12, 615–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M., Ling, Y.-J., & Lee, C.-C. (2024). Does ESG performance and investor attention affect stock volatility? An empirical study based on panel data and mixed—Frequency data. Applied Economics, 57(57), 9728–9742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Prol, J., & Kim, K. (2022). Risk-return performance of optimized ESG equity portfolios in the NYSE. Finance Research Letters, 50, 103312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lublóy, Á., Keresztúri, J. L., & Berlinger, E. (2024). Quantifying firm-level greenwashing: A systematic literature review. Journal of Environmental Management, 373, 123399–123399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundgren, T., & Olsson, R. (2009). How bad is bad news? Assessing the effects of environmental incidents on firm value. American Journal of Finance and Accounting, 1(4), 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, T. P., & Montgomery, A. W. (2015). The means and end of greenwash. Organization & Environment, 28(2), 223–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquis, C., & Toffel, M. W. (2012). When do firms greenwash? Corporate visibility, civil society scrutiny, and environmental disclosure (pp. 11–115). Harvard Business School. [Google Scholar]

- Newell, S. J., Goldsmith, R. E., & Banzhaf, E. J. (1998). The effect of misleading environmental claims on consumer perceptions of advertisements. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 6(2), 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyilasy, G., Gangadharbatla, H., & Paladino, A. (2014). Perceived greenwashing: The interactive effects of green advertising and corporate environmental performance on consumer reactions. Journal of Business Ethics, 125(4), 693–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppong-Tawiah, D., & Webster, J. (2023). Corporate sustainability communication as “Fake News”: Firms’ greenwashing on twitter. Sustainability, 15(8), 6683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramitha, V., Tan, S. Z., & Lim, W. M. (2025). Undoing greenwashing: The roles of greenwashing severity, consumer forgiveness, growth beliefs and apology sincerity. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 34(4), 433–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, W. R. (2008). Approaching adulthood: The maturing of institutional theory. Theory and Society, 37(5), 427–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, M. (1973). Job market signaling. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 87(3), 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoja, E., Polanski, A., & Nguyen, L. H. (2024). The taxonomy of tail risk. Journal of Financial Research, 48(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchman, M. C. (1995). Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. The Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F., Miroshnychenko, I., Barontini, R., & Frey, M. (2018). Does it pay to be a greenwasher or a brownwasher? Business Strategy and the Environment, 27(7), 1104–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treepongkaruna, S., Hwa, H., Thomsen, S., & Kyaw, K. (2024). Greenwashing, carbon emission, and ESG. Business Strategy and the Environment, 33(8), 8526–8539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ung, D., & Abburu, S. (2021). Incorporating ESG considerations in australian equities: A strategic view. Available online: https://www.ssga.com/library-content/pdfs/insights/409759-spdr-incorporating-esg-considerations-final.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Walker, K., & Wan, F. (2012). The harm of symbolic actions and green-washing: Corporate actions and communications on environmental performance and their financial implications. Journal of Business Ethics, 109(2), 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Chen, Y., & Yao, H. (2025). Revealing the veil of greenwashing in ESG reports: Predicting the degree of corporate greenwashing based on thematic and sentiment features of text. IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Computing, 1, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D. (2022). Are firms motivated to greenwash by financial constraints? Evidence from global firms’ data. Journal of International Financial Management & Accounting, 33(3), 459–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M., Zhang, X., & Song, Y. (2025). Do green investments really make companies “green”? Empirical evidence from corporate ESG ratings. Environment, Development and Sustainability. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Definition/Measurement | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Greenwashing Score (GW) | Residual from the regression of ESG score on CO2 emissions | LSEG ESG + Emissions |

| ESG Score | Composite ESG performance score (0–100) | LSEG |

| CO2 Emissions | Scope 1 and 2 emissions (metric tons) | LSEG |

| Firm Risk (RV) | Realized volatility of daily stock returns | LSEG |

| Size (SIZE) | Natural log of total asset | LSEG |

| Profitability (ROA) | Net income/total assets | LSEG |

| Leverage (LEV) | Total debt/total assets | LSEG |

| Book-to-Market (BM) | Book value/market value of equity | LSEG |

| Cash Holdings (CASH HOLD.) | LSEG |

| Variables | Obs. | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variables | |||||

| RV | 1780 | 0.519 | 0.365 | 0.0000 | 5.820 |

| Independent variables | |||||

| GW | 1565 | 22.25 | 22.73 | −31.05 | 133.25 |

| Control variables | |||||

| ROA | 1780 | −0.035 | 0.337 | −8.421 | 0.846 |

| LEV | 1780 | 0.438 | 0.314 | 0.003 | 5.301 |

| SIZE | 1780 | 6.661 | 2.051 | −2.210 | 12.175 |

| BM | 1780 | 11.714 | 165.054 | −9.005 | 4159.596 |

| CASH HOLD. | 1780 | 0.161 | 0.195 | 0.0005 | 1 |

| RV | GW | SIZE | ROA | LEV | CASH HOLD. | BM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RV | 1 | ||||||

| GW | −0.33 *** | 1 | |||||

| SIZE | −0.51 ** | 0.66 *** | 1 | ||||

| ROA | −0.43 *** | 0.22 *** | 0.42 *** | 1 | |||

| LEV | −0.07 *** | 0.049 ** | 0.17 *** | −0.04 | 1 | ||

| CASH HOLD. | 0.28 *** | −0.22 *** | −0.50 *** | −0.36 *** | −0.24 *** | 1 | |

| BM | 0.12 *** | −0.02 | −0.11 *** | −0.02 | −0.04 | 0.03 | 1 |

| Dep. Variable | Indep. Variable | Coefficient |

|---|---|---|

| ESG | CO2 | −0.000002 *** (0.00) |

| ROA | −3.753448 (1.83) | |

| LEV | 2.839214 (2.44) | |

| BM | −0.007241 *** (0.00) | |

| SIZE | 1.727807 ** (0.75) | |

| CASH HOLD. | −2.280936 (1.91) | |

| Obs. | 1385 | |

| AR (2) Stat. | 0.59 (0.56) | |

| Hansen J Stat. | 34.93 (0.33) | |

| Model efficacy | √ |

| Contemporaneous GW (H1) | One-Lag GW | Two-Lag GW (H2) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dep. Variable | Indep. Variable | Coefficient | Dep. Variable | Indep. Variable | Coefficient | Dep. Variable | Indep. Variable | Coefficient |

| RV | GW.ESG | −0.005945 *** (0.002) | RV | L1. GW.ESG | −0.009049 *** (0.003) | RV | L2. GW.ESG | −0.005755 *** (0.002) |

| ROA | −0.1009694 (0.09) | ROA | −0.1116502 (0.07) | ROA | −0.1007269 (0.07) | |||

| LEV | −0.115005 (0.20) | LEV | −0.048623 (0.14) | LEV | −0.025399 (0.14) | |||

| BM | 0.0002181 *** (0.00002) | BM | 0.0001626 *** (0.00002) | BM | 0.0001674 *** (0.00002) | |||

| CASH HOLD. | 0.2501393 *** (0.10) | CASH HOLD. | 0.1769943 (0.12) | CASH HOLD. | 0.310039 *** (0.11) | |||

| Obs. | 1565 | Obs. | 1541 | Obs. | 1381 | |||

| AR (2) Stat. | −0.85 (0.38) | AR (2) Stat. | −1.15 (0.25) | AR (2) Stat. | −1.40 (0.16) | |||

| Hansen J Stat. | 34.15 (0.16) | Hansen J Stat. | 31.45 (0.21) | Hansen J Stat. | 29.13 (0.26) | |||

| Model efficacy | √ | Model efficacy | √ | Model efficacy | √ | |||

| Contemporaneous GW (H1) | One-Lag GW | Two-Lag GW (H2) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dep. Variable | Indep. Variable | Coefficient | Dep. Variable | Indep. Variable | Coefficient | Dep. Variable | Indep. Variable | Coefficient |

| RV | GW.ESG | −0.00444 ** (0.002) | RV | L1. GW.ESG | −0.01128 * (0.006) | RV | L2. GW.ESG | −0.004117 * (0.002) |

| ROA | −0.10692 (0.09) | ROA | −0.12610 * (0.06) | ROA | −0.09512 (0.07) | |||

| LEV | −0.13563 (0.19) | LEV | −0.06473 (0.14) | LEV | −0.06450 (0.13) | |||

| BM | 0.0001648 *** (0.00003) | BM | 0.00016 *** (0.00003) | BM | 0.000106 *** (0.00002) | |||

| CASH HOLD. | 0.03411 (0.10) | CASH HOLD. | 0.13018 (0.15) | CASH HOLD. | −0.02790 (0.11) | |||

| Size | −0.04472 ** (0.02) | Size | 0.00474 (0.05) | Size | −0.057402 ** (0.02) | |||

| Obs. | 1565 | Obs | 1541 | Obs | 1381 | |||

| AR (2) Stat. | −0.89 (0.37) | AR (2) Stat. | −1.17 (0.24) | AR (2) Stat. | −1.40 (0.16) | |||

| Hansen J Stat. | 37.05 (0.09) | Hansen J Stat. | 26.63 (0.43) | Hansen J Stat. | 29.13 (0.26) | |||

| Model efficacy | Partially Valid | Model efficacy | √ | Model efficacy | √ | |||

| Dep. Variable | Indep. Variable | Coefficient |

|---|---|---|

| E Pillar | CO2 | −0.00000343 *** (0.00) |

| ROA | −0.1154556 (0.50) | |

| LEV | −0.9468757 (1.45) | |

| BM | −0.00054 (0.004) | |

| SIZE | 0.6881573 (0.501) | |

| CASH HOLD. | −0.7034515 (1.80) | |

| Obs. | 1385 | |

| AR (2) Stat. | −0.80 (0.43) | |

| Hansen J Stat. | 10.54 (0.23) | |

| Model efficacy | √ |

| Contemporaneous GW (H1) | One-Lag GW | Two-Lag GW (H2) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dep. Variable | Indep. Variable | Coefficient | Dep. Variable | Indep. Variable | Coefficient | Dep. Variable | Indep. Variable | Coefficient |

| RV | GW.EPillar | −0.003334 *** (0.001) | RV | L1. GW.EPillar | −0.0034642 ** (0.002) | RV | L2. GW.EPillar | −0.002649 (0.002) |

| ROA | −0.110749 (0.08) | ROA | −0.0928285 (0.07) | ROA | −0.0902801 (0.08) | |||

| LEV | −0.0869504 (0.21) | LEV | −0.0055118 (0.14) | LEV | −0.007308 (0.14) | |||

| BM | 0.0001998 *** (0.00002) | BM | 0.0001634 (0.00002) | BM | 0.0001657 (0.00002) | |||

| CASH HOLD. | 0.280439 (0.010) | CASH HOLD. | 0.3079485 ** (0.12) | CASH HOLD. | 0.3664208 (0.14) | |||

| Obs. | 1565 | Obs. | 1541 | Obs. | 1381 | |||

| AR (2) Stat. | −0.85 (0.40) | AR (2) Stat. | −1.16 (0.25) | AR (2) Stat. | −1.37 (0.17) | |||

| Hansen J Stat. | 40.0 (0.05) | Hansen J Stat. | 45.15 ** (0.05) | Hansen J Stat. | 47.30 *** (0.01) | |||

| Model efficacy | √ | Model efficacy | √ | Model efficacy | Partially Valid | |||

| Contemporaneous GW (H1) | One-Lag GW | Two-Lag GW (H2) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dep. Variable | Indep. Variable | Coefficient | Dep. Variable | Indep. Variable | Coefficient | Dep. Variable | Indep. Variable | Coefficient |

| RV | GW.ESG | −0.01047 ** (0.05) | RV | L1. GW.ESG | −0.01093 ** (0.005) | RV | L2. GW.ESG | −0.01447 ** (0.006) |

| ROA | −0.17264 *** (0.64) | ROA | −0.20941 *** (0.06) | ROA | −0.23134 *** (0.06) | |||

| LEV | −0.14800 (0.20) | LEV | −0.0673 (0.15) | LEV | −0.08666 (0.15) | |||

| BM | 0.000192 *** (0.00002) | BM | 0.000123 *** (0.00003) | BM | 0.0001026 ** (0.00003) | |||

| CASH HOLD. | 0.4085 (0.20) | CASH HOLD. | 0.02681 (0.19) | CASH HOLD. | 0.35023 *** (0.22) | |||

| Obs. | 1218 | Obs. | 1190 | Obs. | 1029 | |||

| AR (2) Stat. | −0.62 (0.54) | AR (2) Stat. | 0.42 (0.67) | AR (2) Stat. | −1.70 (0.09) | |||

| Hansen J Stat. | 39.86 (0.03) | Hansen J Stat. | 40.80 (0.02) | Hansen J Stat. | 35.56 (0.06) | |||

| Model efficacy | Partially Valid | Model efficacy | Partially Valid | Model efficacy | Partially Valid | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mirza, R.; Bhuiyan, T.; Hoque, A. False Stability? How Greenwashing Shapes Firm Risk in the Short and Long Run. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 691. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18120691

Mirza R, Bhuiyan T, Hoque A. False Stability? How Greenwashing Shapes Firm Risk in the Short and Long Run. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(12):691. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18120691

Chicago/Turabian StyleMirza, Rahma, Tanvir Bhuiyan, and Ariful Hoque. 2025. "False Stability? How Greenwashing Shapes Firm Risk in the Short and Long Run" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 12: 691. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18120691

APA StyleMirza, R., Bhuiyan, T., & Hoque, A. (2025). False Stability? How Greenwashing Shapes Firm Risk in the Short and Long Run. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(12), 691. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18120691