1. Introduction

Volatility forecasting is a fundamental component of modern financial analysis, as it underpins risk management, asset allocation, derivative pricing, and monetary policy decisions. Accurate predictions volatility forecasts help investors and policymakers anticipate uncertainty and make informed strategic choices.

Volatility plays a central role in financial economics because it directly shapes key mechanisms of risk and asset valuation. First, volatility determines the risk premium investors require as compensation for uncertainty, thereby influencing expected returns across asset classes. Second, precise volatility estimates are essential for widely used pricing frameworks—including CAPM, Black-Scholes, and stochastic-volatility models—where volatility enters as a core input. Third, volatility determines the efficiency of portfolio diversification and allocation through mean-variance optimization, making its forecast quality critical for constructing stable, risk-adjusted portfolios. In risk management, volatility is an explicit component of Value-at-Risk (VaR) and Expected Shortfall (ES). Forecasting errors therefore translate directly into miscalibrated capital buffers, producing either understated downside risk or overly conservative capital requirements. As an indicator of market stress, volatility also shapes investor psychology, market liquidity, and transaction costs. Rising volatility widens bid-ask spreads, increases slippage, and reduces market depth. Moreover, volatility acts as a key indicator of market regimes–distinguishing tranquil from turbulent periods–and is widely employed in Markov-switching models to identify state transitions. Persistent increases in volatility help flag crisis conditions and structural breaks, including events such as the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), COVID-19, and inflation shocks. Taken together, these properties illustrate why improvements in volatility forecasting carry both statistical and economic relevance: they enhance pricing accuracy, strengthen portfolio allocation, improve risk measurement, and provide earlier detection of regime shifts and systemic stress.

Traditionally, econometric approaches such as the Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) (

Box & Jenkins, 1970) and the Generalized Autoregressive Conditional Heteroscedasticity (GARCH) (

Engle, 1982;

Bollerslev, 1986) have been widely used, valued for their simplicity and theoretical grounding. ARIMA captures linear dependencies on past values and forecast errors, while GARCH models time-varying variance and the well-known clustering of volatility in financial markets. Extensions such as EGARCH introduce asymmetry by recognizing that negative shocks can in-crease volatility more strongly than positive ones (

Nelson, 1991). However, their parametric and largely linear structure makes them poorly suited for the empirical properties of realized volatility, which include long-memory, nonlinear adjustments and regime-dependent behavior documented extensively in the literature (

Andersen et al., 2003;

O. E. Barndorff-Nielsen & Shephard, 2002;

Andersen et al., 2001). By examining whether AI-based architectures respond more effectively to shifts in volatility regimes than classical econometric models, this study addresses a key economic question: to what extent can model architecture enhance the detection of structural changes, information flows, and market conditions that influence risk-related decisions? This perspective ensures that the comparison across model classes reflects not only statistical accuracy but also the mechanisms through which markets process information.

The model classes considered in this study correspond to established market mechanisms. ARIMA captures short-run autocorrelation in volatility proxies, GARCH models conditional variance and leverage effects, and HAR-RV reproduces long-memory behavior by combining daily, weekly, and monthly components. DL architectures extend these ideas by modelling nonlinear interactions and structural breaks, while Transformer-based models employ self-attention to identify relevant segments of volatility history, making them well suited to abrupt shifts and heterogeneous information flows.

Although models such as Stochastic Volatility, Realized GARCH, GARCH-MIDAS, and HAR-J are well established in the literature, they are not included here to maintain methodological consistency. These models rely on heterogeneous input structures—such as intraday realized measures, jump components, or mixed-frequency information—which are not directly comparable to the daily data framework used in this study Moreover, primary objective of this paper is to compare standard econometric benchmarks with deep-learning and Transformer architectures. Introducing specialized extensions such as MIDAS or Realized GARCH would substantially broaden the scope of the analysis and reduce the clarity and interpretability of the comparison. Importantly, several of the structural features targeted by these advanced econometric models are already absorbed endogenously by modern AI architectures, particularly those with attention mechanisms. For these reasons, the analysis focuses on a consistent and comparable set of models and leaves the exploration of such extensions for future research.

As a primary analytical contribution, the study applies a consistent and unified evaluation framework that implements the same forecasting, generalization, and overfitting diagnostics across classical, deep-learning, and Transformer models. To the extent allowed by the available literature, existing studies typically evaluate these model classes separately, over different time periods, or under non-comparable criteria, which limits direct comparability. Here, a single methodological protocol is applied uniformly to all architectures, enabling a more structured and comparable assessment of their performance under different market conditions.

A further methodological contribution is the use of a multi-estimator framework for realized volatility. Instead of relying on a single proxy, the analysis evaluates all model classes across three established estimators—Close-to-Close, Parkinson, and Yang-Zhang. Based on the available literature, many empirical studies rely on only one estimator, reducing robustness and comparability. By applying an identical forecasting and validation protocol to all three RV measures, the study provides a more robust and estimator-independent assessment of model accuracy and illustrates how different architectures respond to intraday variation, overnight movements, and combined sources of volatility.

An additional contribution is the enriched economic interpretation of the forecasts. The analysis shows how models behave during calm periods—when volatility evolves smoothly—and during crisis regimes, when it becomes sharply nonlinear and shocks intensify. This contrast clarifies which model architectures deliver more timely responses, more stable risk assessments, and more accurate uncertainty estimates under different market conditions. In this way, forecasting accuracy is not evaluated in isolation but is placed within the broader decision-making context relevant for risk managers, investors, and institutional participants.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 reviews the relevant literature;

Section 3 presents the data and methodology;

Section 4 reports the empirical results;

Section 5 provides the economic interpretation of forecast results; and

Section 6 concludes.

2. Literature Review

Volatility forecasting has traditionally relied on classical econometric methods such as GARCH, ARIMA, and their extensions. Reviewing both econometric and deep learning perspectives provides a fuller understanding of how different models capture volatility dynamics. This section reviews key empirical contributions in both volatility forecasting and general time-series modelling, summarised in

Table 1. The empirical literature on volatility can be broadly divided into two main strands. The first encompasses forecasting-oriented studies, which evaluate statistical models such as ARIMA, GARCH, and HAR-RV, as well as more recent deep-learning architectures, with a primary focus on predictive accuracy. The second strand examines the economic nature of volatility itself, including risk premia, volatility-of-volatility, uncertainty shocks, and their macro-financial transmission mechanisms (

Engle et al., 2013). Although these two lines of research are related, they address distinct questions. The present study belongs to the forecasting-oriented literature but also incorporates economic motivation from the second strand in order to strengthen the interpretation and economic relevance of the results.

The GARCH family remains central to volatility modeling and has been extensively applied in both standalone and hybrid forecasting frameworks. Extensions such as EGARCH, GJR-GARCH, and GARCH-MIDAS capture asymmetry and the influence of mixed-frequency macroeconomic factors (

Ersin & Bildirici, 2023;

Asgharian et al., 2013;

Virk et al., 2024). Recent studies suggest that incorporating nonlinear elements through neural-network components, such as LSTM, can further enhance predictive accuracy, significantly improving long-horizon forecasts (

Ersin & Bildirici, 2023). Empirical evidence generally confirms that GARCH-type models outperform linear specifications such as ARIMA when forecasting stock-return variance (

Asgharian et al., 2013). Including macroeconomic variables can enhance long-horizon forecasts but may also lead to overfitting or data-mining bias under certain conditions (

Virk et al., 2024). Recent findings by Bildirici and Ersin confirm that adding LSTM components to GARCH-MIDAS frameworks substantially improves long-horizon performance (

Ersin & Bildirici, 2023). Although ARIMA remains effective for modelling linear dynamics, it struggles to handle abrupt structural changes (

Ferreira & Medeiros, 2021). Nonlinear models such as LSTM can adapt better during such periods, though ARIMA may still outperform LSTM in certain short-term contexts (

Harikumar & Muthumeenakshi, 2025).

Recurrent neural networks, especially long short-term memory (LSTM) architectures (

Hochreiter & Schmidhuber, 1997;

Greff et al., 2017), have shown strong predictive accuracy by learning longer-term dependencies in financial time-series data (

Hochreiter & Schmidhuber, 1997;

Greff et al., 2017;

Z. Zhang et al., 2025). LSTM networks address the vanishing gradient problem through memory cells that preserve long-horizon dynamics, a property relevant to persistent volatility (

Hochreiter & Schmidhuber, 1997;

Greff et al., 2017). Building on this foundation, hybrid convolutional LSTM (CNN-LSTM) models (

Z. Zhang et al., 2025;

Shi et al., 2015;

Borovykh et al., 2017) combine convolutional layers, which extract local features, with recurrent layers that capture temporal structure. This design allows the model to represent short-term movements alongside long-run dependencies.

Transformer-based (TRF) architectures (

Vaswani et al., 2017) have recently advanced sequence modeling by replacing recurrence with attention mechanisms. This approach allows the model to analyze relationships across all time steps simultaneously, making Transformers efficient at capturing both local and global patterns in financial data. For time-series forecasting, the PatchTST framework partitions the input into overlapping patches before applying attention, enhancing computational efficiency for longer-horizon predictions (

Nie et al., 2023). While machine-learning studies document notable forecasting gains, most evaluate narrow model sets, short samples, or single horizons, leaving open important questions about their economic relevance and robustness under varying market regimes (

Chun et al., 2025;

Souto & Moradi, 2024;

Zeng et al., 2023).

Recent evidence shows that Transformer architectures can successfully forecast synthetic Ornstein–Uhlenbeck processes and daily S&P 500 dynamics (

Brugiere & Turinici, 2025). Prior work suggests that Transformers often predict log-quadratic variation more accurately than daily returns (

Brugiere & Turinici, 2025;

Souto & Moradi, 2024). Modern Transformer variants improve scalability and long-horizon accuracy (

Nie et al., 2023). In financial applications, models such as PatchTST, Informer, and Autoformer frequently outperform first-generation Transformers (

Nie et al., 2023;

Souto & Moradi, 2024;

Zeng et al., 2023). Zeng et al. also demonstrates that hybrid CNN-Transformer architectures outperform both traditional deep learning and econometric models when applied to financial time series (

Zeng et al., 2023). A Quant-former model combining sentiment analysis and investor factor construction has been shown to outperform other quantitative factor models in stock-price prediction (

Z. Zhang et al., 2025).

Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) are particularly effective at capturing short-range patterns in time-series data, while Transformers are more effective at modeling long-range dependencies. Recent evidence shows that hybrid CNN-Transformer architectures can combine the advantages of local feature extraction and long-range dependency modelling, outperforming traditional deep-learning and econometric models in financial time-series forecasting (

Zeng et al., 2023). More broadly, machine-learning (ML) models tend to outperform classical volatility models across horizons, though real trading performance may be affected by transaction costs and implementation frictions (

Chun et al., 2025). Chun, Cho, and Ryu also find that ML-based volatility models outperform GARCH and HAR-RV benchmarks across multiple horizons, especially when used for volatility-timing strategies (

Chun et al., 2025).

Recent studies on realized volatility estimation show that multi-grid techniques reduce microstructure noise (

L. Zhang et al., 2005), while combining multiple estimators enhances overall forecast accuracy (

Patton & Sheppard, 2015). Jump-robust measures such as power and bipower variation further enhance volatility estimation and risk measurement (

Patton & Sheppard, 2015;

Tauchen & Zhou, 2011), reflecting the ongoing development of more accurate and robust realized-volatility estimators. Parallel to these econometric developments, recent work has compared ML models (such as LSTM and CNN) with classical approaches for realized-volatility forecasting. However, despite substantial interest in machine-learning applications, empirical research applying Transformer-based architectures specifically to realized-variance forecasting remains limited. This study contributes to this emerging strand by evaluating Transformer, LSTM and CNN-LSTM models alongside representative classical benchmarks (ARIMA, GARCH, HAR-RV) across multiple horizons and major U.S. indices over a long sample (2000–2025).

While the literature provides important insights into volatility modelling, several gaps remain. HAR-RV and GARCH models perform well for short horizons but often weaken during periods of structural change, indicating the need for models that can capture nonlinear and regime-dependent behavior. Recent machine-learning studies report accuracy gains, yet many analyse isolated model families or focus on single indices, limiting cross-model comparability across horizons and market conditions. Although Transformer-based architectures have shown strong results in general time-series forecasting, their application to realized-variance forecasting remains limited. These gaps motivate our unified framework, which jointly evaluates classical econometric, deep-learning, and Transformer models across multiple indices and forecast horizons, enabling a consistent comparison and a clearer economic interpretation of the observed performance differences.

3. Materials and Methods

This section outlines the data sources, preprocessing procedures, and modeling design employed in the study. It describes how RV measures were constructed, how datasets were synchronized across indices, and how econometric, DL, and TRF frameworks were trained and evaluated under a unified experimental setup.

3.1. Data Collation and Preprocessing

The empirical analysis is based on daily price data for 3 major U.S. equity indices (the S&P 500, NASDAQ 100 and DJIA), covering the period from January 2000 to August 2025 (

Table 2). This long historical window provides sufficient depth for constructing multi-horizon volatility forecasts and ensures stable estimation of realized-variance measures. It also captures a wide range of market environments, allowing models to be evaluated under both low- and high-volatility conditions.

The datasets were obtained from

Investing.com (

2025) (

https://www.investing.com/, accessed on 5 September 2025), and include daily open, high, low, and close (OHLC) prices, ensuring full consistency across indices. The series contain 6450 daily observations per index, spanning nearly 25 years of trading data (

Table 2). After applying a 120-day rolling lookback window, around 6300 supervised sequences were produced for three horizons—1, 5, and 22 days (h = 1, 5, 22), representing daily, weekly, and monthly intervals. Logarithmic returns were computed from daily closing prices to capture compounding effects and short-term dynamics.

RV was estimated using three range-based measures: Close-to-Close, Parkinson (

Parkinson, 1980) and Yang–Zhang (

Yang & Zhang, 2000). A logarithmic transformation of realized variance (log(RV) was then applied to stabilize variance, improving model stability and convergence, forming target variable for all models.

While realized variance is theoretically defined as the sum of squared intraday re-turns, we rely on range-based estimators due to the absence of consistent intraday data for the entire period and across all indices. Range-based realized measures (

Parkinson, 1980) have been shown to be high-frequency-efficient and less noisy than close-to-close variance estimates, offering a practical and theoretically justified proxy when only daily OHLC data are available. Consistent with the realized-volatility literature, we therefore treat our dependent variable as a range-based proxy for integrated volatility (

L. Zhang et al., 2005;

Patton & Sheppard, 2009;

O. Barndorff-Nielsen & Shephard, 2004). RV is chosen as the dependent variable because it provides a model-free, data-driven measure of integrated volatility whose asymptotic and finite-sample properties are well established in empirical finance (

Andersen et al., 2003;

O. E. Barndorff-Nielsen & Shephard, 2002;

Andersen et al., 2001). Following Andersen, Bollerslev, Diebold and Labys (

Andersen et al., 2003;

Andersen et al., 2001) and

O. E. Barndorff-Nielsen and Shephard (

2002), RV provides a more accurate benchmark of integrated volatility than squared returns or parametric GARCH-implied variance. Using three complementary RV definitions improves measurement robustness by capturing multiple dimensions of price variation and reducing estimator-specific bias (

L. Zhang et al., 2005;

Andersen et al., 2003;

O. Barndorff-Nielsen & Shephard, 2004).

The choice of the 2000–2025 period is motivated by both statistical and economic considerations. Statistically, a long sample is essential for training deep learning models, and evaluating multi-horizon forecasts, and ensuring stable estimation of realized-variance measures. Economically, this period encompasses several distinct volatility regimes—from the dot-com aftermath and the Global Financial Crisis to the COVID-19 shock and the post-pandemic tightening cycle—allowing us to examine whether AI-based architectures adapt more effectively to structural changes than classical econometric models.

Data were split 80/20 into training and testing sets, with the test sample beginning in August 2020 to capture major high-volatility episodes such as the COVID-19 crisis, the 2022 inflation shock, and the 2023–2025 market adjustment.

Before constructing the target variable, the raw series were cleaned and aligned chronologically. Missing or duplicated rows were removed to ensure consistent and gap-free returns, as such issues can distort both log-return and RV calculations. Daily logarithmic returns were calculated as follows:

where

is the daily closing price. In financial econometrics, realized variance (RV) is theoretically defined as the sum of squared intraday log-returns (

Andersen et al., 2003;

O. E. Barndorff-Nielsen & Shephard, 2002;

Patton, 2011):

Because intraday data are unavailable for the full 2000–2025 sample, RV is approximated using daily information. The simplest approximation is the squared daily log-return (

Patton, 2011):

This approximation captures daily price variability and is widely used in long-horizon studies when intraday data are unavailable. Although high-frequency data can yield finer estimates, daily squared returns offer a reliable long-horizon analysis. To improve measurement quality, two additional range-based estimators are employed—the Parkinson (

Parkinson, 1980) measure and the Yang–Zhang (

Yang & Zhang, 2000) estimator—which use daily high, low, open, and close prices to capture intraday variation when true intraday data are unavailable. These estimators are known to be high-frequency-efficient and less noisy than close-to-close volatility, making them suitable for long-sample forecasting studies studies (

Parkinson, 1980;

L. Zhang et al., 2005;

O. Barndorff-Nielsen & Shephard, 2004). Variance is used instead of volatility because it is additive and provides a more stable modeling scale. Following

Andersen et al. (

2003) and

Patton (

2011), the RV is theoretically defined as the sum of squared intraday returns. Since intraday observations are unavailable, we approximate this quantity using the three daily OHLC-based estimators described above. To stabilize the distribution and reduce skewness, we apply the logarithmic transformation (

Corsi, 2005):

which becomes the dependent variable for all models:

This transformation yields the log-realized variance, which normalizes scale, stabilizes variance, and produces an approximately Gaussian distribution that enhances model performance across both classical and deep-learning frameworks. Moreover, because

is strictly positive, the logarithmic transformation is always well-defined, and forecast values can be mapped back to the variance scale through exponentiation (

Andersen et al., 2003;

Andersen et al., 2001;

Corsi, 2005). After generating predictions in the log-variance domain, forecasts are converted to the RV domain using:

where

t is the current time index and

t +

h denotes the future point corresponding to an

h-step-ahead forecast.

Forecasting log(RV) rather than raw RV is standard in modern financial econometrics due to its improved statistical properties—lower skewness, stabilized variance, and better learning behavior—which contribute to higher predictive accuracy across linear and nonlinear specifications (

Andersen et al., 2003;

O. E. Barndorff-Nielsen & Shephard, 2002;

Corsi, 2005). The resulting forecasts remain interpretable for applications such as volatility targeting and Value-at-Risk estimation.

To ensure comparability across model classes, all input features were standardized using training-sample statistics only. The modeling framework employed a 120-day rolling lookback window and three forecast horizons (h = 1, 5, 22), capturing both short and medium-term volatility persistence. Predicted values were transformed back from the logarithmic to the variance scale for evaluation in risk management contexts (

Table 3). This multi-horizon rolling-window setup is well established in realized-variance forecasting (

Taylor, 2005;

Andersen et al., 2003;

O. E. Barndorff-Nielsen & Shephard, 2002).

Table 3 summarises the main model families considered in the study. The comparison highlights several methodological trade-offs: classical econometric models remain transparent and efficient but struggle with nonlinear dynamics and regime changes; DL models provide greater flexibility but require more data and offer limited interpretability; and TRF architectures deliver strong long-range modelling capacity but are still relatively new in volatility forecasting. To mitigate the black-box limitations of DL and TRF models, the study adopts a transparent and reproducible framework, combining volatility decomposition (Close-to-Close, Parkinson, Yang–Zhang), interpretable loss metrics (QLIKE, MAE, RMSE), and visual diagnostics such as loss curves and true-vs-forecast panels. This ensures that the empirical results remain robust, comparable, and economically meaningful.

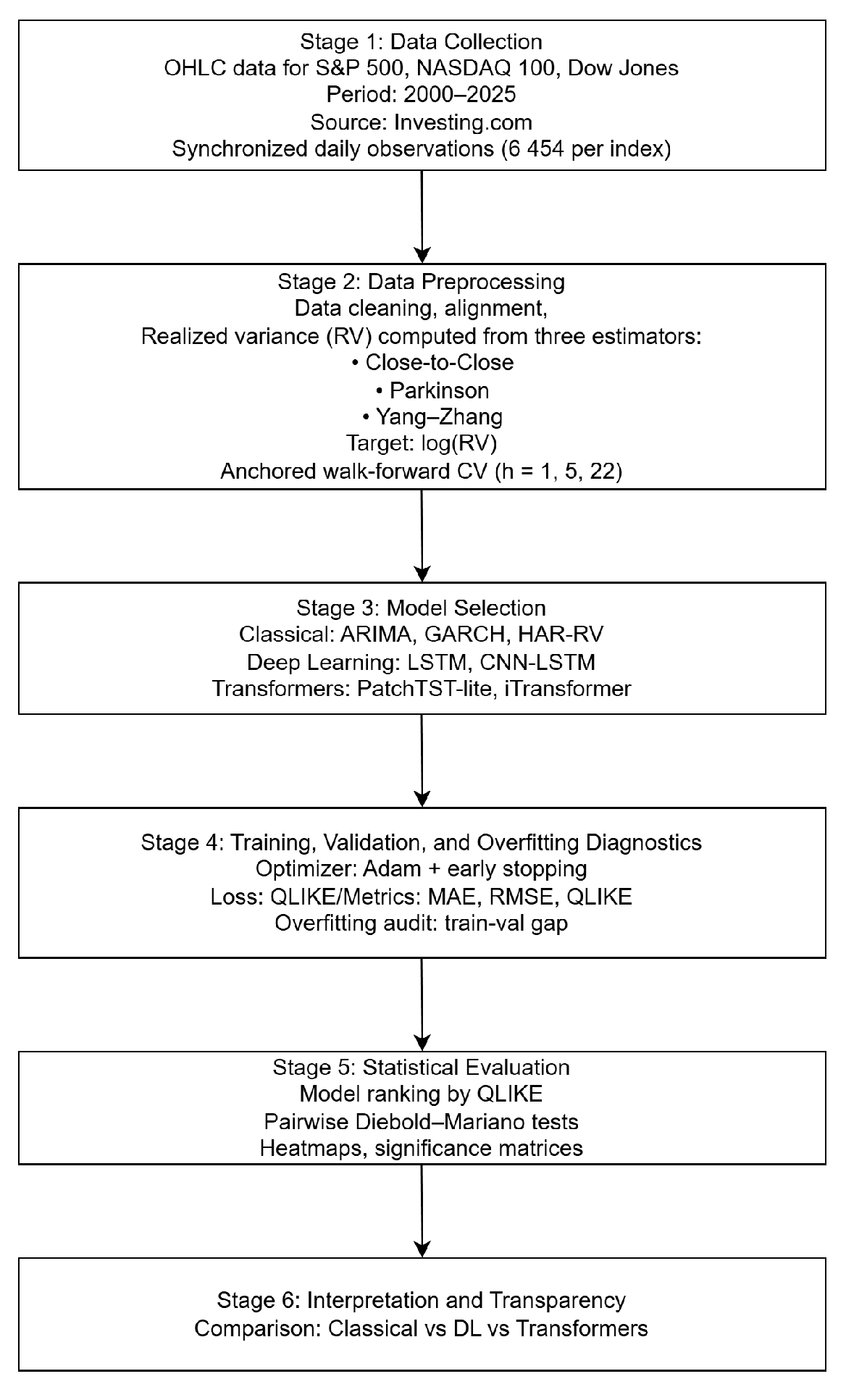

Figure 1 presents the structured workflow adopted in this study, integrating classical econometric methods with contemporary ML and TRF architectures. The framework ensures methodological rigor and comparability across model families. It shows how econometric and AI-based approaches complement each other in capturing volatility dynamics and translating empirical evidence into actionable insights for financial decision-making and policy applications.

3.2. Methodology

The methodology section outlines the analytical framework and modeling strategies employed in this study. It details the structure, estimation procedures, and validation methods applied to three major model groups used to forecast RV across major U.S. indices.

3.2.1. Classical Econometric Models

The ARIMA model (

Box & Jenkins, 1970) is one of the most established tools in financial time-series forecasting. It combines an autoregressive (AR) term, which captures dependence on past observations, a moving average (MA) term, which reflects past forecast errors, and an integration (I) term that ensures stationarity through differencing. Following the classical Box-Jenkins (

Box & Jenkins, 1970) specification, a general non-seasonal ARIMA(

p,

d,

q) process can be written as:

where

L denotes the lag operator,

represents the autoregressive polynomial of order

is the differencing operator applied

d times, and

denotes the moving average polynomial of order

q. The innovation term

is assumed to be independently and identically distributed with zero mean and variance

.

Although ARIMA models are often applied to returns, in volatility forecasting it is more appropriate to model the logarithm of realized log(RV). This transformation stabilizes variance and reduces skewness, improving linear model performance when capturing persistence in RV (

Taylor, 2005;

Andersen et al., 2003;

O. E. Barndorff-Nielsen & Shephard, 2002;

Andersen et al., 2001). The use of log(RV) is well established in the realized-variance literature and generally produces more interpretable forecasts than modeling prices or returns directly (

Andersen et al., 2003;

O. E. Barndorff-Nielsen & Shephard, 2002). ARIMA provides a fundamental baseline, effectively capturing linear dependencies and short-term autocorrelation in the conditional mean. However, they assume constant variance, which is unrealistic for financial data characterized by volatility clustering. To address this,

Engle (

1982) introduced the ARCH model, later generalized by

Bollerslev (

1986) into the GARCH framework.

While ARIMA models the conditional mean, GARCH models the conditional variance, capturing how volatility evolves over time. This enables GARCH to represent persistent volatility and time-varying risk. In practice, the two models are often combined—ARIMA captures mean dynamics, and GARCH models residual volatility—yielding a more complete description of financial time series. In practice, the GARCH (1,1) specification is the most widely used:

Here, α measures the immediate impact of new shocks, while β reflects volatility persistence. This compact and flexible specification allows GARCH to complement ARIMA. In this study, GARCH(1,1) is estimated on daily log-returns, and its conditional variance is compared against the log(RV) targets derived from the three realized-variance estimators.

While ARIMA and GARCH remain essential tools for modeling linear dependence and conditional heteroskedasticity (

Box & Jenkins, 1970;

Engle, 1982;

Bollerslev, 1986), they are limited in capturing long-memory effects and regime shifts often present in RV. To address this,

Corsi (

2009) introduced the HAR-RV, which incorporates volatility components over multiple horizons.

Formally:

where

,

, and

represent the realized variance computed over daily, weekly and monthly intervals, respectively.

The HAR-RV model bridges the simplicity of traditional econometrics with the ability to capture long-memory dynamics, serving as a robust benchmark before moving to nonlinear and DL models.

3.2.2. Advanced Models

To complement classical econometric methods, this study employs ML and DL models designed to capture nonlinear dependencies and long-range dynamics frequently observed in RV. These approaches are well suited to volatility forecasting, where regime shifts, structural breaks, and asymmetric responses to shocks are common.

The LSTM network (

Hochreiter & Schmidhuber, 1997) models persistent volatility patterns through memory cells and gating mechanisms that preserve long-range information. A hybrid CNN-LSTM architecture (

Shi et al., 2015) is also implemented: convolutional layers extract short-term local variations, while LSTM layers capture slower-moving components. Both models are trained on log(RV) using the QLIKE loss, which is standard for variance forecasting. Its core update rule can be summarized as (

Greff et al., 2017):

where

represents the memory cell,

and

represent the forget and input gates, and

is the candidate state.

Following

Y. Zhang et al. (

2025), the model uses RV as the target variable, while the convolutional layer extracts local temporal features using the CNN-LSTM hybrid architecture. In line with

Borovykh et al. (

2017), the architecture first applies one-dimensional convolutional filters to capture local temporal features:

where

are learnable convolutional kernels of length

K, which act as sliding filters that move across the input sequence to extract local temporal features;

are then passed to the LSTM layer, which models long-term dependencies.

Transformer models (

Vaswani et al., 2017) use self-attention to evaluate pairwise dependencies across the entire input window without recurrence. This enables them to capture both local and global patterns in log(RV). The study employs two compact variants: a lightweight encoder and the PatchTST-lite model (

Nie et al., 2023), which partitions the input into overlapping patches to increase efficiency and improve long-horizon forecasting. Following

Nie et al. (

2023), we implement a lightweight version of the PatchTST architecture (PatchTST-lite) by adopting the reduced embedding size, fewer encoder blocks, and simplified attention configuration recommended in the original implementation, which preserves predictive performance while substantially lowering computational cost. Both models are trained on log(RV) using the QLIKE loss and evaluated via anchored walk-forward validation (

Nie et al., 2023), where the training window remains fixed and the test window moves forward in time. Given a sequence of inputs

, the self-attention mechanism maps it into contextualized representations (

Vaswani et al., 2017):

where

, and

are the query, key, and value matrices.

Building on the CNN-LSTM framework, which captures short-term volatility bursts and longer-term persistence, the PatchTST-lite Transformer extends this idea by dividing the input into overlapping patches processed through multi-head self-attention (

Nie et al., 2023). This structure allows the model to learn both local and global patterns in log(RV). The final prediction is obtained from the encoder output:

where

denotes the patch representations and

is the forecast horizon. PatchTST-lite reduces attention complexity from

to

, improving scalability for long input windows.

In this study, both Transformer variants—a lightweight encoder and PatchTST-lite—are trained on log(RV) using the QLIKE loss, and evaluated through anchored walk-forward validation (

Nie et al., 2023). This procedure closely mirrors real-world forecasting, as the training sample expands over time. To strengthen inference, we also conduct regime-specific evaluation (calm vs. turbulent periods) and apply Diebold-Mariano (

Diebold & Mariano, 1995) tests to assess the significance of model-performance differences.

4. Results

The empirical results in this section compare the forecasting performance of the econometric models across multiple horizons and volatility regimes. The evaluation framework integrates three complementary dimensions: forecast accuracy, statistical significance, and model reliability. Forecast accuracy is assessed using MAE, RMSE, and QLIKE, which quantify how closely model predictions track realized volatility. The DM test (

Diebold & Mariano, 1995) determines whether differences in forecast errors between model pairs are statistically significant. Model reliability is examined through overfitting diagnostics, comparing in-sample and out-of-sample losses to assess generalization quality. This three-layer framework provides a transparent and coherent basis for comparing classical and data-driven models across all volatility estimators and horizons.

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Preliminary Analysis

Before evaluating the forecasting models, we examine how RV behaves across the three indices: S&P 500, NASDAQ 100, and DJIA. Three RV estimators are used: Close-to-Close, Parkinson, and Yang–Zhang. All RV measures are analyzed in log form to stabilize variance and reduce extreme values. The descriptive analysis reveals that RV is strongly right-skewed and leptokurtic across all indices, indicating that extreme volatility spikes occur far more often than expected under a normal distribution. The mean values exceed the medians, confirming heavy right tails, while dispersion measures vary substantially over time. These features reflect volatility clustering—tranquil periods followed by abrupt spikes. Even after log-transformation, the series display heterogeneity and outliers, consistent with fat-tailed volatility distributions. When examining the time dynamics of logRV, we observe gradually decaying autocorrelations and persistent shocks, implying that the underlying processes are mean-reverting but exhibit long memory. This pattern is more pronounced in range-based estimators, which incorporate intraday variation indirectly. This helps explain why models such as HAR-RV and GARCH(1,1) perform reliably: both depend on serial correlation.

Formal cross-correlation matrices and unit-root tests were not included, as these diagnostics fall outside the primary objective of the study, which is to compare forecasting models rather than to analyse inter-index dependence or long-run stochastic properties. The use of log-transformed realized volatility is well established in the literature to yield stationary, mean-reverting series suitable for econometric and machine-learning forecasting frameworks. Given the stable statistical behavior of the series and the extensive empirical evidence supporting their stationarity, additional correlation and stationarity tests were deemed unnecessary for the purposes of this analysis.

4.2. Classical Model Performance

This subsection examines the empirical performance of the classical econometric models. The evaluation focuses on forecast accuracy (MAE, RMSE, QLIKE), overfitting diagnostics, and overall model behavior across horizons and volatility regimes.

4.2.1. Point Forecast Accuracy (MAE, RMSE, QLIKE)

Forecast accuracy is evaluated using MAE, RMSE, and QLIKE loss.

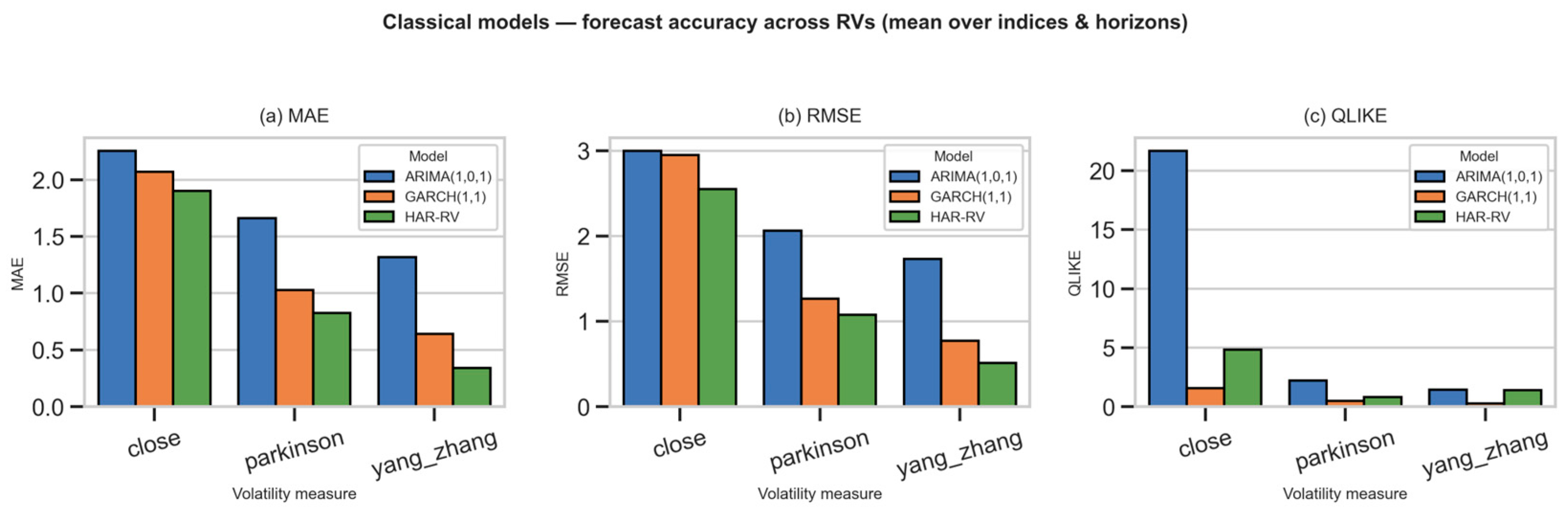

Figure 2 presents the average performance of ARIMA(1,0,1), GARCH(1,1), and HAR-RV models across the three realized-volatility estimators (Close, Parkinson, and Yang–Zhang), aggregated over all indices and forecast horizons (h = 1, 5, 22). The results show a clear and consistent pattern: HAR-RV achieves the lowest MAE and RMSE values, confirming its strong ability to capture multi-scale volatility dynamics. By incorporating lagged RV terms, the HAR-RV adjusts more smoothly to persistent volatility patterns, leading to better short and medium-term forecasts. GARCH(1,1) delivers moderate results compared with ARIMA(1,0,1), and reduces forecast errors more effectively than ARIMA(1,0,1), but remains less accurate than HAR-RV (

Appendix A Table A1). Its QLIKE values remain low, reflecting good clustering capture but weaker amplitude precision. ARIMA(1,0,1) systematically exhibits the highest error values in all three metrics, indicating limited adaptability to heteroskedastic behavior. Among the RV estimators, the Yang–Zhang measure yields the lowest overall errors, indicating superior sensitivity to daily and overnight price variation and providing the most stable target dynamics for classical models.

In summary, these results confirm that the strong persistence of RV is essential for reliable volatility forecasts. HAR-RV provides the most robust classical benchmark, while ARIMA remains limited by its inability to adapt to time-varying volatility.

4.2.2. Statistical Significance (DM Test)

The DM test evaluates whether two competing models generate significantly different forecast errors over the same evaluation period. A low

p-value (below 0.05) indicates that the models differ significantly, while higher values suggest that their forecasts are statistically similar (

Appendix A Table A2).

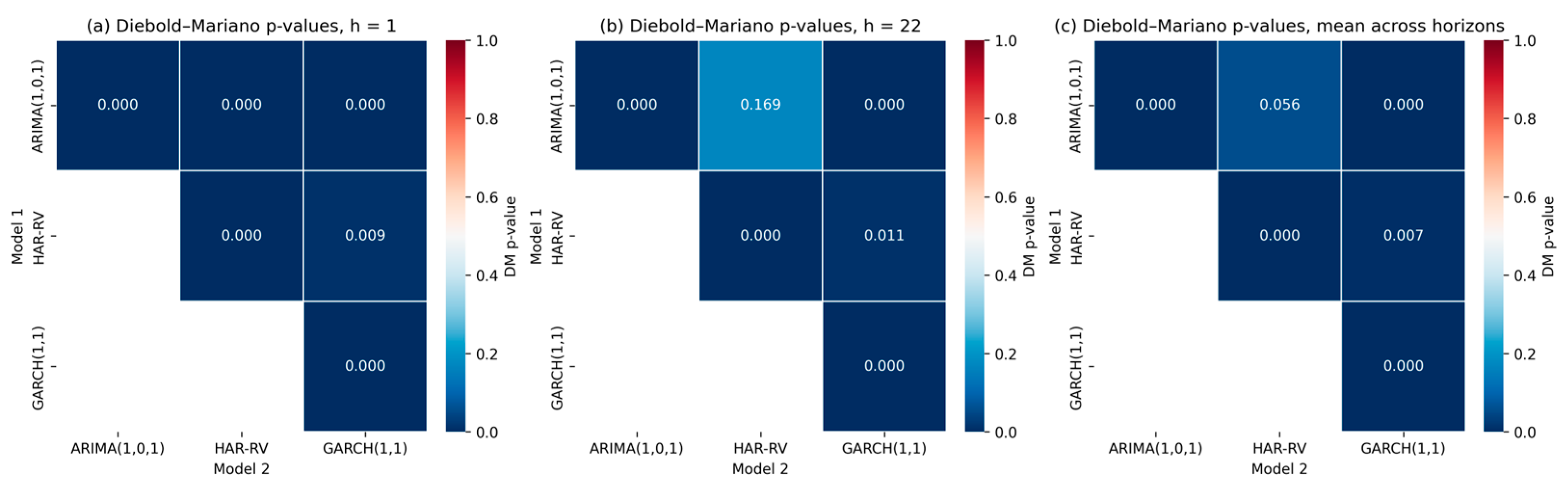

Figure 3 presents pairwise

p-values for all model comparisons. At the short horizon (h = 1), almost all model comparisons show highly significant differences (

p ≈ 0.000). This confirms that all three classical models generate clearly distinct short-term forecasts. The largest contrast appears between HAR-RV and GARCH(1,1), emphasizing the role of lagged RV terms in improving short-horizon prediction. At the long horizon (h = 22), statistical differences weaken. The

p-value between ARIMA and HAR-RV (

p ≈ 0.17) shows that their long-run forecasts are statistically similar. In contrast, GARCH(1,1) remains significantly different from both models, reflecting its stronger dependence on persistence dynamics. The average heatmap across all horizons supports these observations: HAR-RV and GARCH remain statistically distinct, whereas ARIMA and HAR-RV converge as the forecast horizon increases.

Overall, the DM test confirms that the classical models are not interchangeable. HAR-RV consistently delivers superior short-term accuracy, ARIMA(1,0,1) becomes comparable at medium and long horizons, and GARCH(1,1) captures volatility persistence but does not exceed HAR-RV in accuracy.

4.2.3. Overfitting Diagnostics for Classical Models

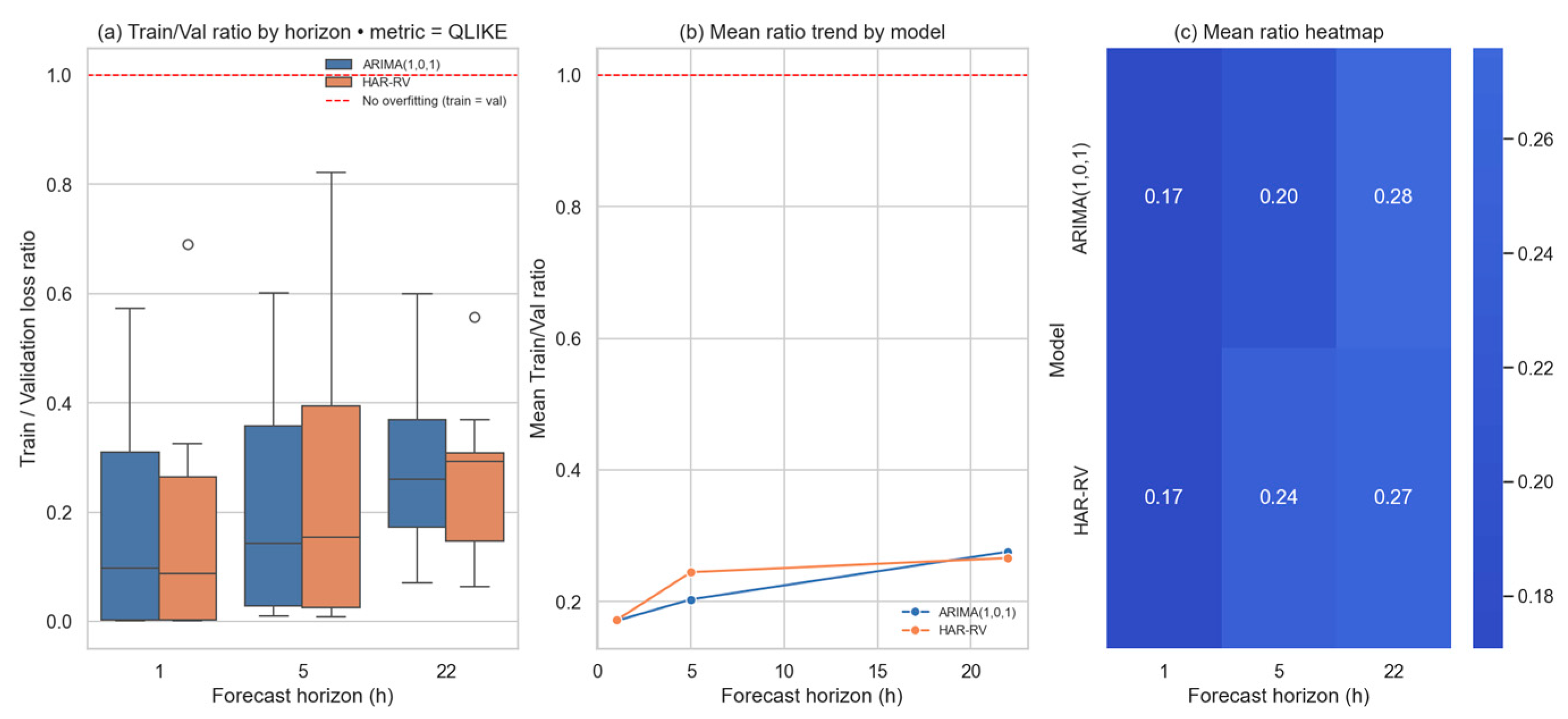

Model robustness is assessed through in-sample and out-of-sample QLIKE losses for ARIMA(1,0,1), GARCH(1,1), and HAR-RV (

Figure 4). A Train/Test ratio close to 1 signals good generalization, while substantial deviations indicate mis-specification. The diagnostics combine out-of-sample losses, train/test ratios, rolling-window behavior, and parameter-path stability as complementary indicators of robustness. Residual portmanteau tests (e.g., Ljung–Box) are not included, as they serve a supportive rather than decisive role in forecasting evaluation.

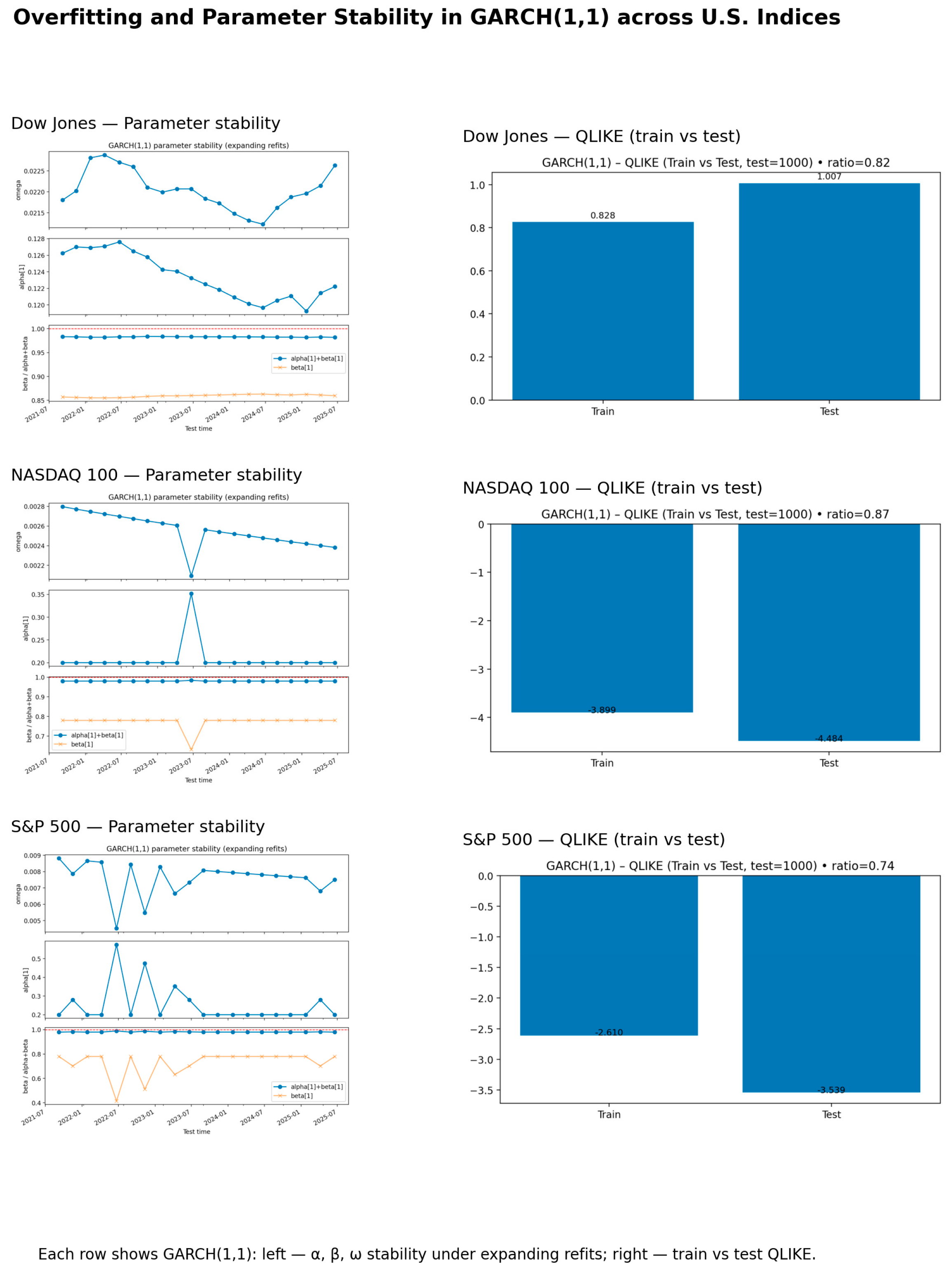

Figure 5 reports parameter stability and QLIKE-based diagnostics for the GARCH(1,1) model applied to the S&P 500, NASDAQ 100, and DJIA. The left panels track the evolution of

and

under expanding-window refits. Across all indices, the persistence term

remains below 1, confirming covariance stationarity and stable conditional-variance dynamics. The right panels display train and test QLIKE losses. Ratios between 0.74 and 0.87 remain below 1, confirming mild and well-controlled overfitting and strong generalization performance.

Overall, the overfitting diagnostics indicate that all classical models generalize well and remain stable across market conditions. Train/Test QLIKE ratios below one, together with stable parameter paths, show that these models capture persistent volatility dynamics without fitting noise. From a financial perspective, this confirms that ARIMA(1,0,1), HAR-RV, and GARCH(1,1) produce reliable volatility estimates that are robust to shifts in market regimes—an essential property for risk management, trading strategies, and forecasting applications.

4.2.4. Forecasting Results

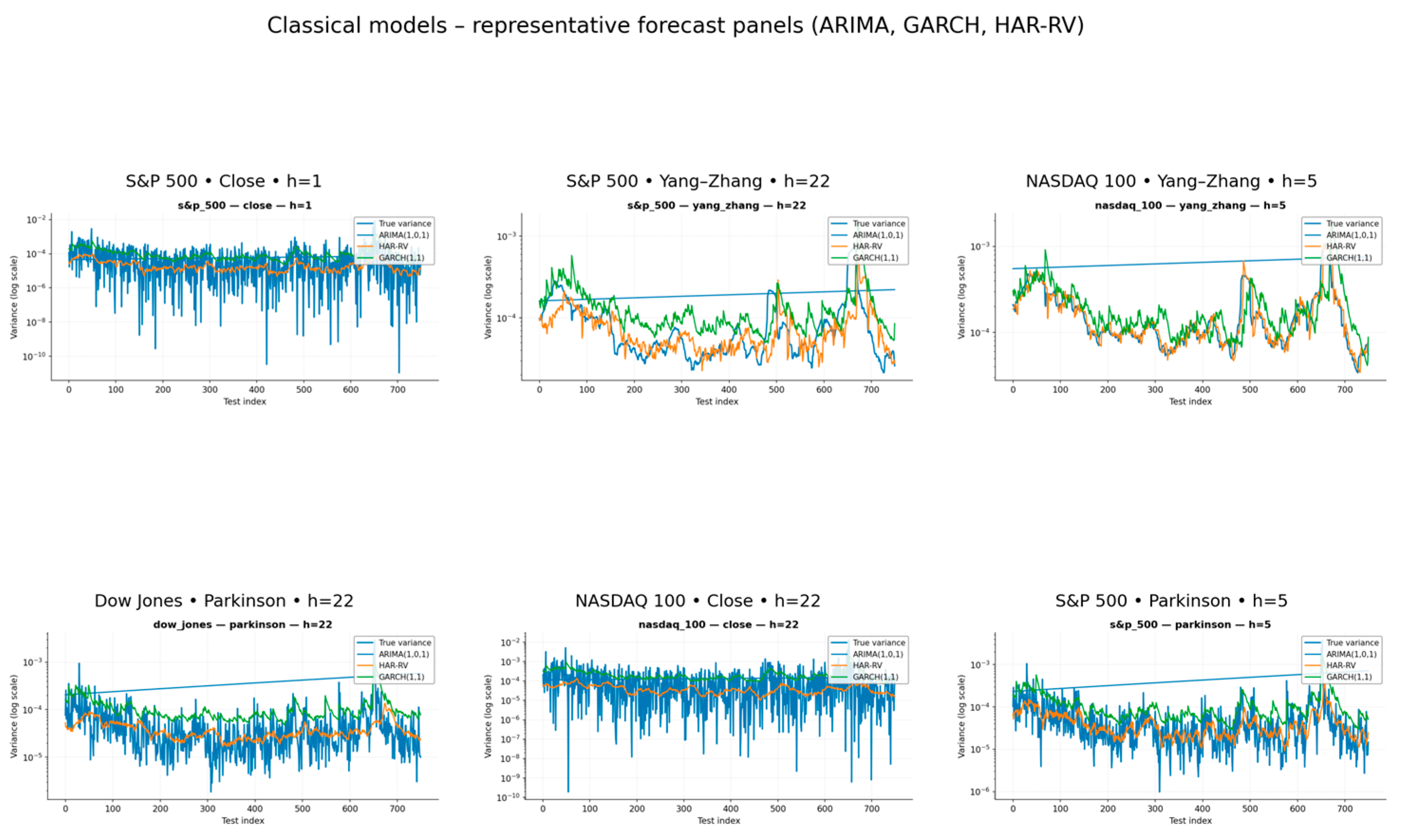

The forecasting performance of the classical models confirms the conclusions drawn from the error and overfitting analyses. Across all indices, RV displays clear clustering and persistence patterns, which ARIMA(1,0,1) captures only partially. GARCH(1,1) adapts better to variance shifts and follows observed peaks and troughs more closely, especially during volatility spikes. However, its forecasts tend to revert too quickly toward the mean, leading to underestimation during extended high-volatility periods. In contrast, the HAR-RV model delivers the smoothest and most consistent forecasts, effectively tracing the underlying volatility dynamics across both short and medium horizons. Its multi-lag structure enables it to incorporate long-term memory effects, which improves synchronization with RV, particularly for the Yang–Zhang estimator provides a stable representation of long-range dependence and filters short-term noise more effectively than ARIMA and GARCH. To further illustrate these dynamics,

Figure 6 presents representative forecast panels for ARIMA(1,0,1), GARCH(1,1), and HAR-RV across three major U.S. indices and three RV estimators (Close, Parkinson, Yang–Zhang) over forecast horizons of h = 1, 5, 22 days. The plots show the logarithmic variance (true vs. predicted) and demonstrate how each model captures volatility movements at different time scales.

Across all indices, HAR-RV consistently aligns most closely with realized variance. Its use of multi-period lags allows for smoother yet responsive adaptation to volatility persistence, effectively capturing both short-term spikes and gradual shifts with relatively low error dispersion. GARCH(1,1) also models volatility clustering well, though it tends to overreact in calm periods and slightly underestimate prolonged extremes during turbulent episodes. This moderate bias is particularly visible in high-volatility windows, where GARCH reverts too rapidly toward its conditional mean. ARIMA(1,0,1), by contrast, produces flatter and less adaptive forecasts, reflecting its linear structure and limited ability to capture volatility feedback effects. As a result, its predictions deviate more strongly from RV, especially for short-horizon forecasts. At longer horizons (h = 22), both HAR-RV and GARCH(1,1) maintain coherent predictive patterns, while ARIMA forecasts gradually diverge from RV, confirming the superior robustness of models explicitly built on variance dynamics. Among the RV estimators, Yang–Zhang yields the smallest and most stable forecast errors across models, suggesting that its inclusion of both overnight and intraday information improves the detection of persistent variance components. These forecasting patterns are consistent across all three indices and reinforce the advantages of RV-based models when long-memory effects are present. Combined with the overfitting diagnostics, these results motivate the transition toward AI-based architectures capable of capturing nonlinear dependencies and regime-specific volatility patterns.

4.3. Advanced Models Performance

This section examines the empirical performance of the advanced models—DL and TRF architectures. These approaches are designed to capture nonlinearities, long-term dependencies, and complex interactions within realized variance (RV) that linear econometric models often fail to represent. The evaluation covers three main dimensions: (1) forecast accuracy across horizons (h = 1, 5, 22), (2) training stability and convergence, and (3) statistical significance of performance differences based on the DM test. All models are trained on log-realized variance and validated using an anchored walk-forward procedure, which expands the training window sequentially while keeping the initial anchor point fixed. This approach reflects realistic forecasting conditions and ensures consistent out-of-sample evaluation.

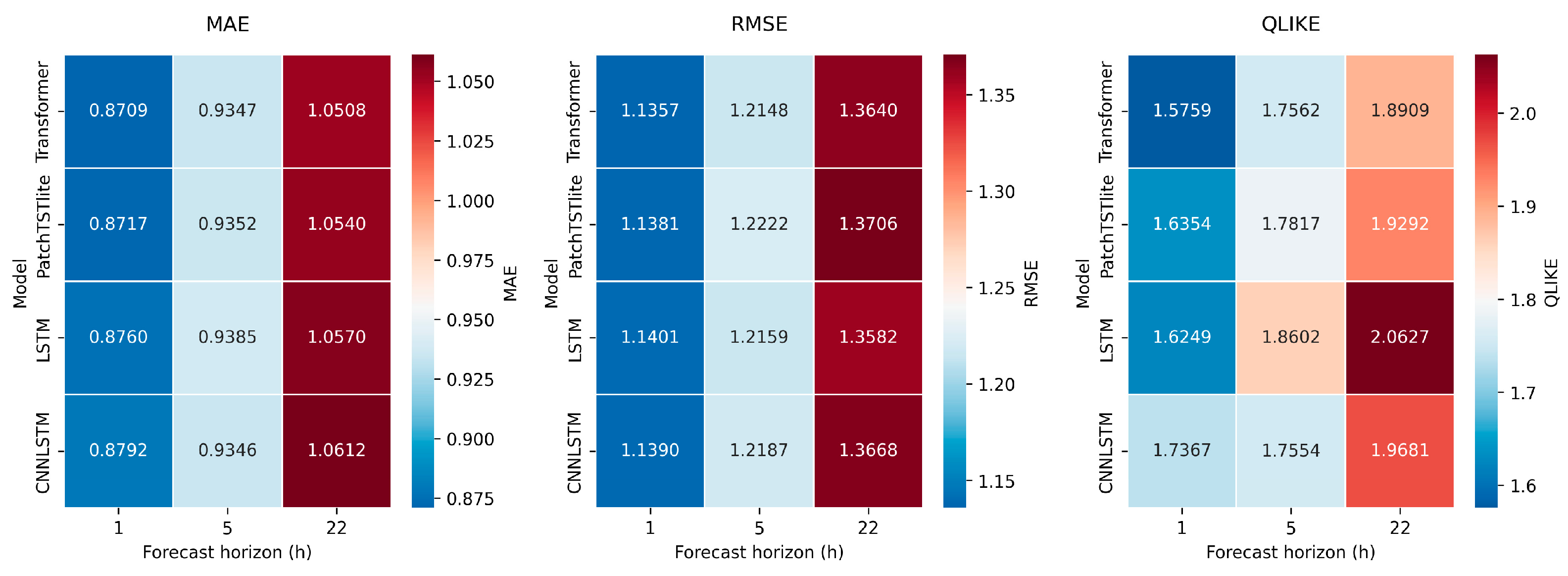

4.3.1. Forecast Accuracy for Advanced Models (MAE, RMSE, QLIKE)

Figure 7 summarizes the aggregated results across all indices and realized variance estimators. Each cell in the heatmap reports the mean error value for a given model and horizon, with darker blue shades corresponding to lower errors (i.e., stronger predictive performance). The Transformer and PatchTST-lite architectures consistently achieve the lowest error values across all metrics, with the advantage becoming particularly pronounced at longer horizons (h = 22), where recurrent models gradually lose calibration. The LSTM model performs competitively at short horizons (h = 1) but loses accuracy as the horizon extends. In contrast, CNN-LSTM exhibits the weakest calibration overall, reflected in its higher RMSE and QLIKE losses (

Appendix A Table A3) These results indicate that attention-based architectures outperform recurrent and convolutional models by better capturing multi-scale temporal dependencies and the nonlinear persistence characteristic of financial volatility.

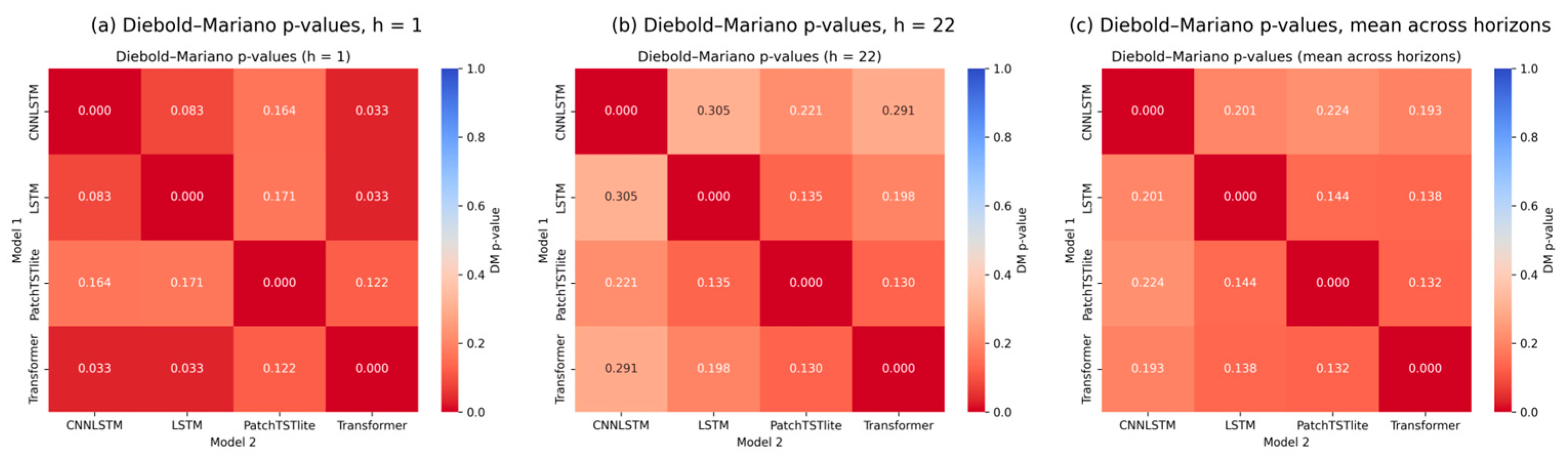

4.3.2. Statistical Significance (Diebold–Mariano)

To verify whether the observed differences in forecasting accuracy are statistically meaningful, the DM test is applied across all horizons and RV measures. The DM statistic compares the forecast loss differentials between pairs of models: positive values indicate that the model in the row performs better, while negative values imply weaker performance.

Figure 8 presents pairwise DM statistics for horizons h = 1, 5, 22, together with the aggregated mean heatmap. Each cell in the heatmap showsthe mean DM value between two models. Warmer colors (red) signal statistically significant outperformance of the row model (

p < 0.05), whereas cooler colors (blue) indicate the opposite. At short horizons (h = 1), differences in predictive accuracy are generally minor, suggesting that most architectures adapt similarly to near-term volatility fluctuations. However, as the horizon increases (h = 5 and h = 22), Transformer and PatchTST-lite show consistently superior and statistically significant performance relative to the recurrent models. This reflects their stronger ability to model long-term persistence and nonlinear variance dynamics. Among all models, CNN-LSTM performs the weakest, showing predominantly negative DM values relative to its counterparts.

As the forecast horizon lengthens, performance differences become clearer and more systematic. While all models perform similarly over short horizons (h = 1), the Transformer and PatchTST-lite architectures gain a clear advantage at medium and long horizons (h = 5, 22). Their ability to capture long-term dependencies and persistent volatility dynamics translates into statistically significant improvements over the recurrent models.

4.3.3. Overfitting Diagnostics for Deep Learning Models

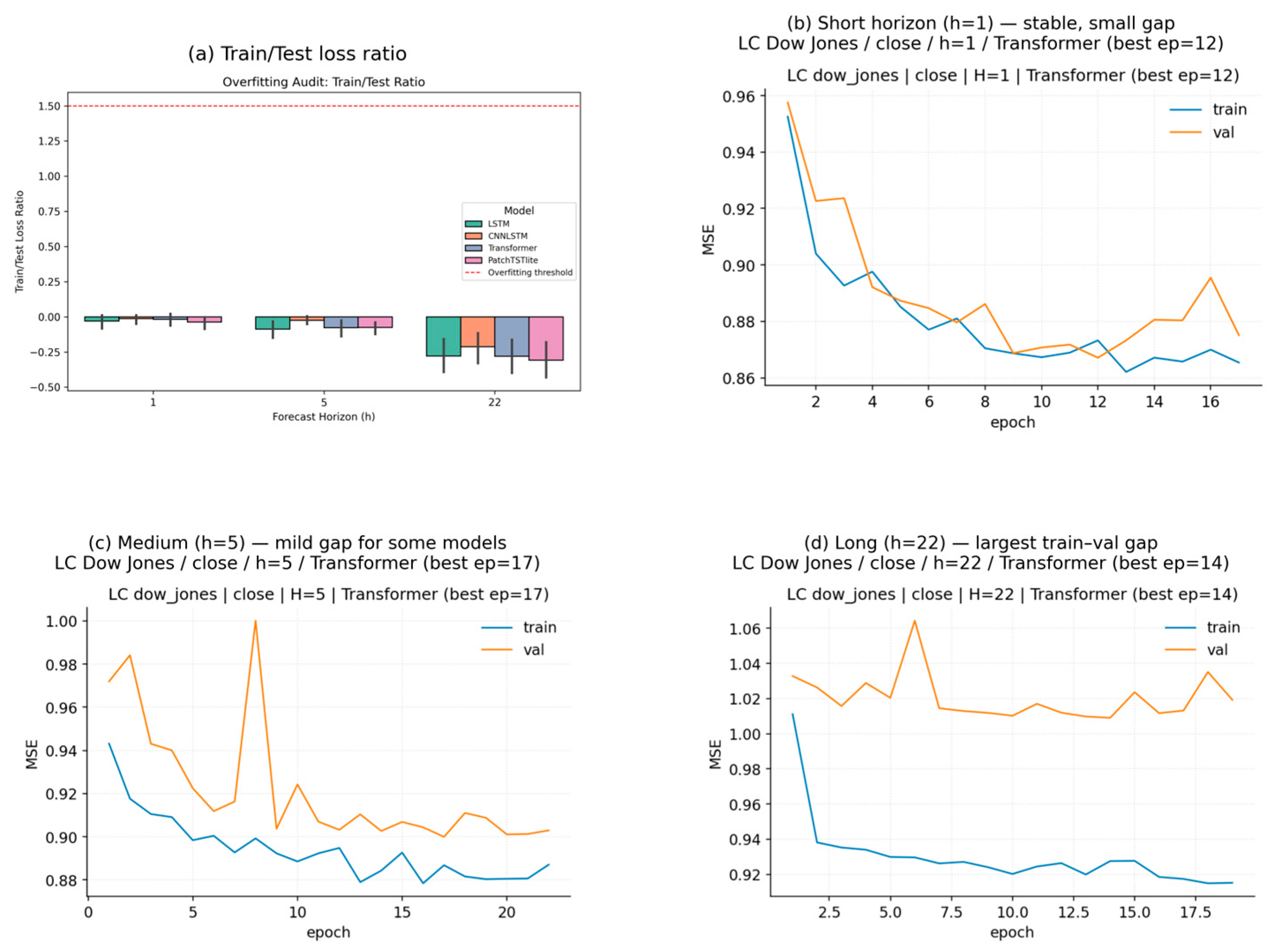

To verify that the DL models produce reliable and stable forecasts, an overfitting audit was conducted. The purpose of this analysis is to assess whether the models learn structural patterns in volatility instead of memorizing the training data. For this reason, both the Train/Test loss ratios and the learning curves were examined across forecast horizons (h = 1, 5, 22).

Figure 9 provides a visual overview of model generalization and stability across horizons. In Panel (a), the average Train/Test loss ratios remain close to one and below the red reference line, indicating a balanced relationship between training and test losses and suggesting that the models do not overfit to a meaningful extent. As the forecast horizon increases (h = 22), the uncertainty bands widen slightly, which is expected when predicting further into the future. At the short horizon (h = 1), both training and validation losses decline quickly and converge within 8–10 epochs, with minimal difference between them. This pattern indicates stable learning dynamics and only minor overfitting, making additional regularization unnecessary. At the medium horizon (h = 5), the validation loss begins to plateau earlier than the training loss, creating a small but visible gap between the two. This suggests mild overfitting, which could be mitigated through small increases in dropout, weight decay, or early stopping. At the long horizon (h = 22), the gap between training and validation losses becomes clearer. While the training loss continues to decrease, the validation loss remains higher and more volatile, indicating partial overfitting. In this case, lower learning rates and stronger regularization, or a shorter input window may help stabilize learning.

Overall, the DL models generalize well at short horizons, show some divergence at medium horizons, and require tighter regularization for longer-term forecasts. These diagnostics confirm that the networks are generally well-calibrated and exhibit only modest overfitting as the forecasting horizon and model difficulty increases.

4.3.4. Forecasting Results

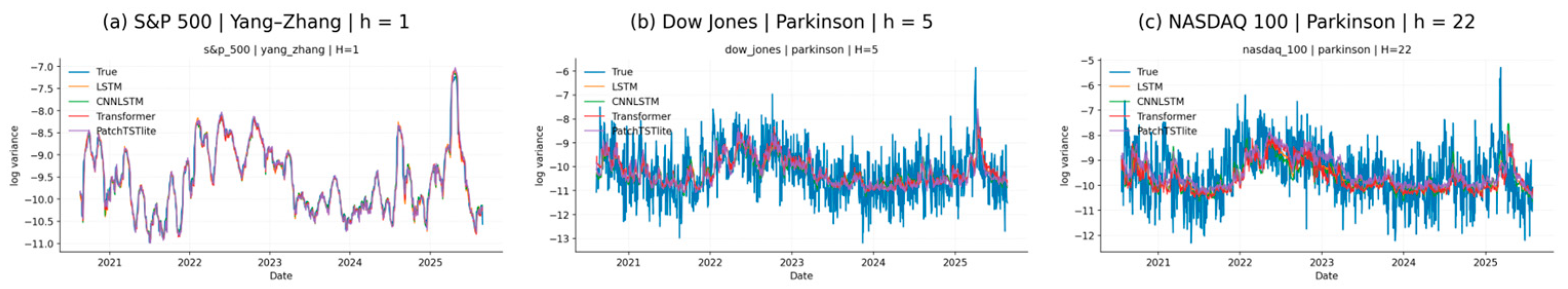

To complement the quantitative evaluation,

Figure 10 illustrates the predicted and RV trajectories for representative cases across the three forecast horizons (h = 1, 5, 22). These visual comparisons provide an intuitive view of how each model tracks volatility fluctuations and responds to volatility clusters and regime. All models were trained and validated using an anchored walk-forward procedure to ensure a realistic, time-consistent evaluation of out-of-sample performance. Model complexity was controlled through early stopping and out-of-sample validation to limit overfitting.

At the short horizon (Panel a,

Figure 10, h = 1), both Transformer and LSTM follow the realized variance closely, capturing most short-lived volatility bursts. Their forecasts react quickly to new information and exhibit minimal delay after market shocks, reflecting strong sensitivity to high-frequency dynamics. At the medium horizon (Panel b, h = 5), forecasts become smoother and less reactive to short-term noise. The PatchTST-lite model maintains consistent alignment with the overall variance level, while recurrent architectures (LSTM and CNN-LSTM) show lagged responses and tend to underpredict during turbulent episodes. This behavior suggests that attention-based models integrate information more effectively across multiple time scales. At the long horizon (Panel c, h = 22), all models naturally show wider deviations from realized variance due to accumulated forecast uncertainty. Nevertheless, the Transformer continues to reproduce broad volatility regimes more accurately than the other architectures. It captures both the persistence of calm periods and the amplitude of volatility spikes, demonstrating robust adaptability even at longer horizons.

Taken together, the visual results confirm the quantitative findings: attention-based models such as Transformer and PatchTST-lite deliver more stable and well-calibrated volatility forecasts across horizons, whereas recurrent models perform well in short-term dynamics but gradually lose precision as the forecast horizon lengthens.

4.4. Comparative Evaluation and Statistical Significance

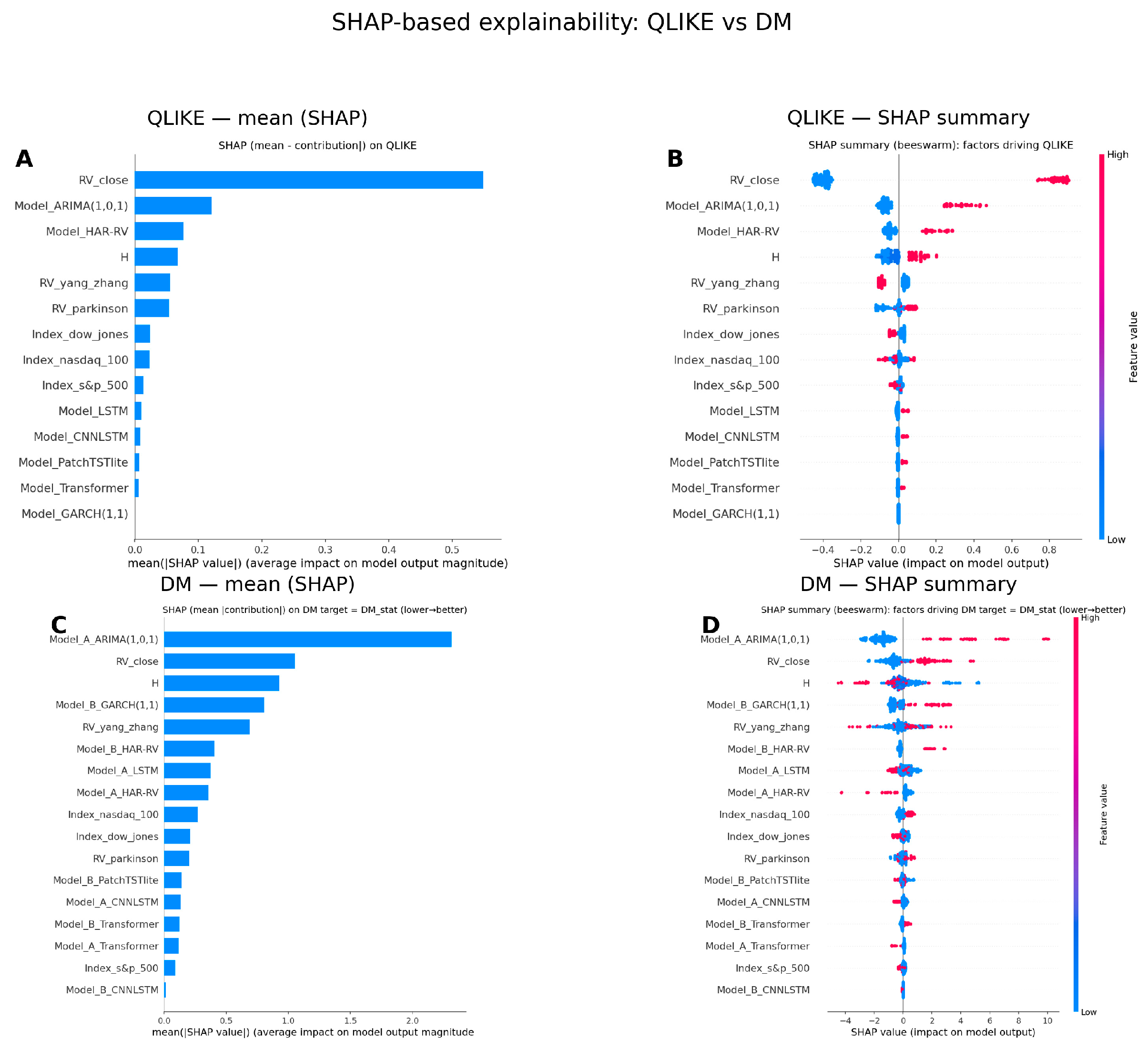

To complement the statistical testing, this section applies SHAP analysis to understand which factors drive model performance and forecast error variability across datasets (

Figure 11). For QLIKE, the analysis reveals that

is the dominant determinant of forecasting accuracy, followed by ARIMA(1,0,1) and HAR-RV, while the forecast horizon H exerts a smaller but consistent influence. The choice of index has little impact on error magnitude, indicating that differences in performance are primarily driven by model architecture and the specification of the RV measure, rather than by market-specific characteristics. For the DM statistic, the largest SHAP contributions come from ARIMA(1,0,1) and

, indicating that these features explain most of the statistical differences between models. GARCH(1,1) and HAR-RV also rank highly, confirming that classical econometric frameworks continue to provide robust benchmarks for comparative evaluation.

In contrast, DL architectures exhibit smaller individual SHAP contributions, implying that their predictive strength stems from broader multi-feature interactions rather than reliance on a single dominant driver. Across both QLIKE and DM metrics, the SHAP patterns consistently show that volatility-based inputs (e.g., , Yang–Zhang) remain key predictors of accuracy, while the choice of model family determines whether these improvements become statistically significant. Short horizons (h = 1, 5) contribute more strongly to DM dominance, whereas long horizons (h = 22) tend to dilute these differences due to higher forecast uncertainty.

The SHAP bar and beeswarm plots offer complementary insights: the mean (SHAP) bars highlight the relative importance of each factor, while the beeswarm plots capture the direction and variability of their effects. Higher SHAP values indicate factors that increase forecasting errors, whereas negative values correspond to better accuracy. The close similarity between QLIKE and DM SHAP patterns confirms that the same underlying factors shape both absolute error size and relative model dominance. Overall, the findings show that model architecture—rather than index choice or horizon length—is the key determinant of forecasting quality. The SHAP results therefore reinforce the broader empirical conclusion: attention-based models, particularly PatchTST-lite, achieve the most reliable and accurate volatility forecasts by leveraging rich, multi-feature interactions rather than isolated predictors.

4.5. Subsample Robustness Analysis

The sample is divided into four economically distinct periods: pre-GFC (2000–2006), GFC (2007–2009), post-GFC (2010–2019), and the COVID-19 period (2020–2025). For each subsample, we recompute the QLIKE error for the best-performing classical model and the best DL architecture (

Table 4).

Across all regimes, the ranking of models remains broadly consistent. HAR-RV delivers the lowest classical-model errors during tranquil periods, when volatility persistence dominates and shocks are moderate. GARCH(1,1) becomes the strongest classical benchmark during crisis episodes such as the GFC and COVID-19, reflecting its ability to respond rapidly to large volatility shocks. Among the advanced models, Transformer-based architectures consistently achieve the lowest QLIKE errors in stress periods, particularly when volatility shifts rapidly and exhibits nonlinear propagation. At shorter horizons in calm regimes, recurrent models such as LSTM and CNN-LSTM perform competitively, but their advantage diminishes during turbulent periods and as the forecast horizon increases.

These results indicate that the main conclusions of the study are not driven by a single historical window. Instead, the model rankings remain stable across major economic regimes, confirming that (a) classical models outperform in stable, low-volatility conditions, while (b) Transformers dominate in crisis-driven and high-uncertainty environments, where long-range dependencies and nonlinear dynamics become critical.

The variation in best-performing models across subsamples reflects differences in market regimes. During tranquil periods (Pre-GFC and Post-GFC), long-memory dynamics dominate and HAR-RV achieves the lowest QLIKE errors, whereas in crisis environments (GFC, COVID-19) GARCH(1,1) performs best because it reacts more rapidly to sudden volatility shocks. Since QLIKE penalizes volatility underestimation, regime shifts naturally lead to changes in the model ranking.

5. Economic Interpretations of Forecast Results

From the perspective of volatility forecasting and market dynamics, the comparison of predictive models reveals several economic mechanisms that shape the behavior of financial uncertainty. Volatility does not evolve smoothly over time; instead, it clusters into prolonged calm periods followed by episodes of heightened turbulence. This well-documented clustering phenomenon explains why investors cycle between increased risk-taking during tranquil phases and heightened caution when volatility rises. Because volatility directly influences risk premia, investor behavior, and the speed at which information is incorporated into asset prices, improvements in forecasting accuracy carry clear economic, rather than purely statistical, relevance.

Traditional econometric models such as GARCH(1,1) and HAR-RV remain reliable baselines for capturing persistence and volatility clustering (

Ersin & Bildirici, 2023;

Asgharian et al., 2013;

Virk et al., 2024). They react to recent shocks and incorporate long-memory components, making them useful for understanding how markets up-date risk assessments.

The strong performance of Transformer-based architectures shows that volatility is driven not merely by random shocks, but by the way financial news and macroeconomic events propagate through markets—unevenly, in waves, and with varying in-tensity. Investor reactions are asymmetric: negative news often triggers sharp overreactions, while positive information is absorbed more gradually. Transformers capture these informational cascades, behavioral asymmetries, and long-memory effects far more effectively than classical linear models. As a result, the empirical findings relate directly to themes of market efficiency, asymmetric information transmission, and the economics of uncertainty.

Because classical models rely on fixed parametric structures they struggle to detect abrupt regime shifts, asymmetric responses to bad news, and structural breaks that increasingly characterize modern markets. During macroeconomic shocks, geopolitical events, or panic-driven sell-offs, these models tend to react too slowly, leading to underestimated risk premia and delayed adjustments in investor positioning.

In terms of news processing, differences in forecast accuracy reveal that classical models implicitly assume smooth information arrival and linear shock propagation (

Ersin & Bildirici, 2023;

Asgharian et al., 2013;

Virk et al., 2024), which explains their weaker performance during crisis episodes. Attention-based architectures, by contrast, extract relevant signals from irregular and clustered news flows, enabling them to adapt to state-dependent information dynamics. Their superior accuracy suggests that markets react selectively, rather than uniformly—a view aligned with behavioral finance and regime-dependent risk pricing.

The economic implications extend directly to risk management and portfolio construction. More accurate volatility forecasts improve the calibration of VaR and ES, reduce the risk of underestimating losses, and support timely adjustments in leverage, margin requirements, and exposure limits. Transformer models detect volatility spikes earlier than GARCH, LSTM, or CNN-LSTM, allowing faster deleveraging and more effective crisis responses (

Nie et al., 2023;

Zeng et al., 2023). In volatility-managed strategies, models that recognize regime changes early provide a notable advantage: because portfolio exposure scales inversely with expected volatility, earlier detection of spikes leads to higher risk-adjusted performance—an area where Transformers consistently outperform other frameworks.

Deep-learning models such as LSTM and CNN-LSTM capture nonlinear and non-stationary dynamics well (

Harikumar & Muthumeenakshi, 2025) because they learn hidden dependencies, repeated patterns, and sudden shifts in market behavior. However, their performance depends strongly on the choice of window length (e.g., 20, 60, or 120 days). Short windows cause the model to overweight recent events and overestimate volatility, leading to excessive caution and lost return opportunities. Long windows overly smooth shocks, causing delayed reactions—especially in crises, when rapid de-risking is critical. Their sensitivity to data scaling can also distort shock magnitude and delay portfolio adjustments. Thus, despite their strong nonlinear capabilities, their forecasts may be less stable under extreme market conditions.

In contrast, Transformer models generalize far more robustly across horizons and market regimes because they do not rely on a fixed time window or on sequential data processing. Their self-attention mechanism allows them to compare all observations simultaneously and extract the most relevant signals from the entire series, whether the market is calm or highly turbulent. This enables them to capture both local shocks and global regime shifts–even when these occur abruptly.

From a financial standpoint, this capability is essential: the model automatically in-creases attention to accelerating price movements, rising cross-asset correlations, negative-news clusters, and growing liquidity stress. Transformers therefore detect early signs of risk-off behavior, widening risk premia, and mounting market uncertainty much faster than recurrent and classical models. This results in earlier reductions in exposure, more precise VaR and ES estimates, and more agile portfolio-management decisions during periods when accuracy is most valuable.

Among all tested models, PatchTST-lite delivers the strongest out-of-sample performance across indices and horizons. This is consistent with evidence that time-series transformers such as Informer and Autoformer capture long-range dependencies more effectively while avoiding the gradient-decay limitations of recurrent networks (

Nie et al., 2023;

Zeng et al., 2023). Low QLIKE and RMSE values across the S&P 500, NASDAQ 100, and DJIA confirm their ability to model regime changes and the dynamics of uncertainty.

Finally, consistent with literature on realized volatility and multi-estimator frame-works (

L. Zhang et al., 2005;

Patton & Sheppard, 2009;

O. Barndorff-Nielsen & Shephard, 2004;

Tauchen & Zhou, 2011), forecasting accuracy improves when diverse volatility signals are combined–such as daily returns, range-based measures, extreme price moves, volume pressure, news shocks, and shifts in correlations. HAR models achieve this through multi-scale aggregation, while attention-based models learn these heterogeneous components directly. Integrating these sources provides a more complete representation of market risk, leading to improved estimation of risk premia, more efficient exposure management, and earlier detection of emerging market stress.

In sum, the superior accuracy of attention-based architectures indicates that financial volatility is driven by long-memory dynamics, nonlinear information flows, regime shifts, and asymmetric investor reactions. Models capable of learning these mechanisms produce forecasts that more accurately reflect the economic structure of uncertainty.

6. Conclusions

This study provides a unified empirical comparison of classical econometric models, DL architectures, and modern Transformer frameworks in forecasting realized variance for major U.S. equity indices. The results show that model architecture is a central determinant of forecasting accuracy and robustness across horizons. Classical models such as GARCH(1,1) and HAR-RV remain reliable baselines under stable market conditions, where persistence and multi-scale variance dynamics dominate. However, their flexibility is limited during turbulent periods and structural breaks.

DL models enhance predictive accuracy by capturing nonlinearities and long-range dependencies in volatility dynamics, yet the shift toward attention-based architectures represents a substantive methodological transition. Lightweight Transformer variants such as PatchTST-lite demonstrate stronger generalization, greater adaptability to regime changes, and more stable performance across horizons. Their ability to learn long-memory effects, nonlinear information propagation, and heterogeneous investor reactions allows them to outperform both classical and recurrent neural models.

The findings carry important implications for practitioners and policymakers. More accurate volatility forecasts strengthen risk-management practices, improve exposure-scaling rules, and support more reliable calibration of VaR and ES during turbulent periods. Since volatility is a key state variable for risk premia and capital allocation, models capable of capturing regime-dependent dynamics provide earlier and more informative signals about shifting market uncertainty and investor behavior. The strong performance of Transformer architectures highlights the growing relevance of explainable AI in volatility modeling and contributes to bridging the gap between predictive accuracy and economic interpretability.

The study also identifies several limitations that open avenues for further research. First, range-based realized-volatility measures rely on daily OHLC data and do not fully capture intraday variation. Second, the empirical evaluation focuses on statistical accuracy rather than economic backtesting through volatility-managed strategies, option-hedging experiments, or extended VaR/ES validation. Third, despite their strong performance, Transformer models remain relatively opaque, motivating future work on hybrid designs that embed structural economic constraints.

Promising directions for future research include integrating Transformer-based volatility forecasts into option-pricing and risk-management frameworks, assessing their impact on implied-volatility surfaces and dynamic-hedging accuracy, and extending model design to incorporate macro-financial variables, sentiment indicators, or high-frequency realized measures.

Switching-regime models and economically constrained Transformers also represent an important avenue, as they can detect abrupt market transitions, capture asymmetric volatility responses (leverage effects), and model time-varying risk premia. These features bring models closer to real-world financial behavior, where risk, uncertainty, and investor reactions depend on the prevailing regime rather than remaining constant.

Overall, the evidence shows that attention-based architectures represent the next generation of volatility-forecasting tools. Their combination of predictive accuracy, scalability, and economic relevance enhances the methodological toolkit and deepens our understanding of how financial markets process information and transmit uncertainty across regimes.