1. Introduction

In recent years, promoting household participation in risky financial markets has been viewed as an important avenue for enhancing property income and advancing common prosperity. Nevertheless, Chinese households’ participation in risky financial markets remains markedly limited. Data from 2019 show that only about 12% of Chinese households held risky financial assets, a figure significantly below the average participation rate of roughly 50% observed in developed economies. This disparity highlights the widespread persistence of “limited participation.”

Extensive research, both domestically and internationally, has examined this phenomenon and produced four main explanatory frameworks. First is the market friction perspective, which argues that supply-side barriers prompt some households to rationally withdraw from risky financial markets. These barriers include information asymmetry, high transaction costs, underdeveloped financial infrastructure, and credit constraints (

Allen & Gale, 1994;

Roche et al., 2013;

Hu et al., 2024). Second is the background risk perspective, which suggests that households exposed to risks that cannot be mitigated through diversification typically demonstrate lower risk tolerance, thereby reducing or avoiding participation in risky markets (

Heaton & Lucas, 2000;

Rosen & Wu, 2004;

Qiu, 2016). Third is the behavioral factors perspective, which challenges the classical assumption of the “perfectly rational agent” and emphasizes that behavioral attributes, such as social interactions and risk attitudes, critically influence household investment decisions. (

Changwony et al., 2015;

Mu et al., 2019). Fourth is the information-processing capability perspective, which highlights that in an era of increasingly complex financial products and rapidly expanding information, a household’s capacity to identify, assimilate, and effectively use financial information is a decisive determinant of its participation in risky investments (

Grinblatt et al., 2011;

Wang et al., 2023).

Based on this framework, this study employs machine learning methods to construct an analytical model encompassing 21 core variables across five dimensions: foundational characteristics, wealth status, comprehensive literacy, behavioral preferences, and regional development. Previous studies have provided valuable insights into the determinants of household participation in risky financial markets; however, most rely on linear econometric approaches that are limited in capturing nonlinear effects, higher-order interactions, and threshold dynamics. Moreover, existing literature seldom links model predictors to underlying behavioral mechanisms, particularly across heterogeneous groups such as urban and rural households.

This study integrates multiple machine learning models with interpretable tools to uncover the nonlinear and interactive relationships that shape household investment decisions. The central hypothesis posits that household participation in risky financial markets is jointly driven by multiple factors whose effects are inherently nonlinear, and that the driving forces and constraints differ across household types. The empirical results reveal that economic attention, income level, urban–rural location, social interactions, educational attainment, and financial literacy are the primary driving forces. To further clarify the complex operational mechanisms, this study investigates the interaction effects among key characteristics and identifies two substantively significant types of moderating effects. The first is the reversal effect of urban–rural disparities. Empirical evidence shows that the impact of urban–rural location on household participation is not absolute. The participation advantage of urban households emerges only when certain conditions are satisfied: sufficient economic attention, income above a defined threshold, and adequate social interaction. The second is the threshold effect of educational attainment and financial literacy. Empirical results demonstrate that heightened attention to economic and financial information does not automatically translate into investment behavior; such translation requires a foundational level of both education and financial literacy. Moreover, this study analyzes the dynamic evolution of participation determinants across different household types, taking into account both life-cycle stages and the urban–rural divide.

2. Literature Review

Academic research on the phenomenon of “limited participation” in household risky financial markets has primarily examined four explanatory dimensions: market frictions, background risks, behavioral factors, and information-processing capabilities.

2.1. Market Friction Perspective

The market friction perspective emphasizes macro-level constraints, arguing that the “frictionless market” assumption underlying classical portfolio theory diverges sharply from real-world conditions. In practice, frictions such as transaction costs, information asymmetries, underdeveloped financial systems, and credit constraints create substantial obstacles to household participation in risky financial markets. Regarding transaction and information costs,

Allen and Gale (

1994) incorporated fixed costs into their theoretical model and demonstrated that such costs discourage participation among liquidity-preferring households by reducing market liquidity and amplifying price volatility.

Bogan (

2008) further identified these costs as a key driver of low participation, noting that internet technologies help mitigate them.

Duraj et al. (

2025) employed a mixed-methods approach to further demonstrate that even when these objective frictions are reduced, subjective perceived frictions persist. Subsequent research expanded the concept of market frictions. For example,

Haliassos and Michaelides (

2003) employed an infinite-horizon dynamic optimization model to show that credit-constrained households exhibit a stronger preference for safety and liquidity, leading them to allocate disproportionately to risk-free financial assets. This tendency is especially pronounced among younger households (

Roche et al., 2013). Evidence also suggests that insufficient financial development restricts household participation in risky markets (

Antzoulatos & Tsoumas, 2010;

Hu et al., 2024).

2.2. Background Risk Perspective

In recent years, household finance research has increasingly focused on non-financial risks. Such risks are difficult to mitigate through diversification or hedging.

Heaton and Lucas (

2000) introduced the notion of background risk, defining it as exposure stemming from non-tradable assets such as labor income, entrepreneurial activities, or real estate. Using calibrated models, they showed that such risks significantly reduce household allocations to risky assets, particularly equities. With respect to income risk,

Guiso et al. (

1996) provided empirical evidence that non-diversifiable labor income risk leads investors to scale back their holdings of risky financial assets. Regarding housing, most studies suggest that real estate investment exerts a crowding-out effect on financial asset allocation (

Cocco, 2005;

Yao & Zhang, 2005). In contrast,

Vestman (

2019) argues that homeownership itself does not lead to a decrease in stock market participation; rather, it is households’ inherent preferences and wealth accumulation capacity that determine their investment behavior. Broadening the concept of background risk,

Rosen and Wu (

2004) incorporated health status, showing that households in poorer health generally allocate less wealth to risky assets. Notably, insurance, serving as a key risk management mechanism, can indirectly facilitate household participation in risky financial markets by mitigating expenditure uncertainty and overall risk exposure (

Qiu, 2016).

2.3. Behavioral Factors Perspective

The behavioral perspective argues that decision-making biases, shaped by psychological traits such as social networks and risk preferences, play a critical role in household participation in risky financial markets. With respect to social interaction,

Biggart and Castanias (

2001) suggested that moderate social engagement serves as a form of “collateral” in financial transactions, enhancing trust and reducing information asymmetry, thereby promoting participation.

Changwony et al. (

2015) further examined the heterogeneity of social influence, finding that membership in social groups significantly increases the likelihood of household investment in risky financial assets, whereas the frequency of informal neighborhood interactions has no significant effect. In contrast,

Bernardo and Welch (

2001) argued that excessive reliance on social networks may lead investors to abandon independent judgment, resulting in cognitive biases and behavioral constraints in decision-making. Turning to risk preference,

Gomes and Michaelides (

2005) employed a life-cycle model to show that even affluent but highly risk-averse households display a markedly lower propensity to invest in risky markets. Building on this perspective,

Mu et al. (

2019) developed a dynamic model of wealth-dependent risk aversion and skewness preference. By solving an extended Hamilton–Jacobi–Bellman (HJB) equation, the study demonstrated that investor preferences evolve with wealth accumulation, thereby altering portfolio allocations to risk and skewness.

2.4. Information-Processing Capability Perspective

The information-processing perspective focuses on households’ ability to identify, absorb, and apply information in complex financial environments. This ability directly shapes their capacity to overcome cognitive and informational barriers to entering risky financial markets. The literature generally distinguishes between innate and acquired information-processing skills. With respect to innate ability,

Grinblatt et al. (

2011) found a positive correlation between cognitive ability, the scale of household stock investment, and the resulting Sharpe ratio. Their findings suggest that households with stronger cognitive ability process information more efficiently and achieve superior performance in risky financial investments. Regarding acquired ability,

Mankiw and Zeldes (

1991) argued that educational attainment is a key channel for developing such skills, as longer schooling reduces information-related barriers and increases the likelihood of participation in risky markets. Subsequent studies broadened the notion of acquired capability to encompass financial and digital literacy. For example,

Van Rooij et al. (

2011), using Dutch household survey data, showed that only a small fraction of households possessed advanced financial knowledge, and that lower financial literacy was strongly associated with a reduced probability of stock market participation. Similarly,

Wang et al. (

2023), analyzing Chinese household survey data, reported that higher digital literacy increases risky asset holdings among middle-aged and older investors.

2.5. Literature Review and Marginal Contributions

In summary, prior studies have examined the phenomenon of “limited participation” in risky financial markets from four principal perspectives: market frictions, background risk, behavioral factors, and information-processing capabilities. Although the international literature offers valuable insights, existing research on Chinese households’ participation in risky financial markets still faces two major limitations. First, prior studies often adopt a narrow analytical scope, focusing primarily on the independent effects of single factors while overlooking systematic comparisons of the relative importance of multidimensional determinants. Chinese households are typically subject to multiple concurrent constraints, including market frictions, background risks, and limited information-processing capacity, and the lack of comprehensive comparison makes it difficult to identify which determinants exert the strongest influence in alleviating limited participation. Second, methodological approaches remain relatively homogeneous, relying mainly on traditional explanatory models that are insufficient for capturing nonlinear relationships and complex interaction patterns. Moreover, these methods have not adequately explored how underlying mechanisms evolve dynamically across heterogeneous population groups.

To address these research gaps, this study makes four key contributions. First, moving beyond single-dimensional perspective, this study integrates four dimensions: market frictions, background risks, behavioral factors, and information-processing capabilities to comprehensively evaluate the relative influence of these factors on limited participation and to identify the key driving variables. Second, it investigates complex interrelationships among variables, with particular emphasis on nonlinear associations and interaction effects. In doing so, the study identifies distinctive patterns such as reversal effects and threshold conditions, thereby advancing understanding of the mechanisms shaping household risk-taking. Third, it incorporates population heterogeneity by analyzing structural differences in influence mechanisms across household life-cycle stages and the urban–rural divide, thus providing a theoretical foundation for targeted policy interventions. Fourth, it introduces methodological innovation by applying diverse machine learning frameworks. Compared with traditional approaches, these methods are better equipped to address high-dimensional data, nonlinear structures, and variable interactions, thereby filling methodological gaps in the existing literature.

3. Machine Learning Framework

This study employs four machine learning techniques: LASSO Regression, XGBoost, Random Forests, and Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) to predict household participation in risky financial markets. Together, these models span a methodological spectrum from sparse linear frameworks to highly nonlinear structures, thereby striking different balances among assumption strength, model complexity, and interpretability.

Specifically, LASSO Regression represents a sparse linear framework capable of variable selection and regularization, serving as a benchmark for linear relationships. Random Forest and XGBoost are ensemble tree-based methods that model nonlinearities and high-order interactions, with Random Forest emphasizing variance reduction through bagging and XGBoost focusing on bias correction through boosting. MLP, a feedforward neural network, captures complex nonlinear mappings and feature compositions beyond the reach of tree-based models.

Following standard notation, the analytical framework can be expressed as

where

denotes whether household

participates in risky financial markets (1 = yes, 0 = no), and

represents the

explanatory variable among the 21 indicators across five dimensions, including foundational characteristics, wealth status, comprehensive literacy, behavioral preferences, and regional development. The function

is approximated by machine learning algorithms such as LASSO, Random Forest, XGBoost, and MLP.

To further elucidate the mechanisms underlying prediction, the analysis incorporates SHAP values and the Accumulated Local Effects (ALE) algorithm to identify critical determinants and delineate predictive patterns. Model interpretability is crucial for uncovering potential causal mechanisms. Interpretable approaches enable researchers to identify the direction, magnitude, and interactions of feature effects, thereby understanding how changes in specific features are associated with variations in household investment behavior. By linking feature contributions to theoretical constructs, interpretability bridges the gap between predictive performance and causal understanding.

The SHAP approach, originally proposed by

Lundberg and Lee (

2017), attributes a fair and consistent “contribution value” to each feature by computing the weighted average of its marginal contributions across all possible feature subsets. Formally, for a feature set

comprising

features and a given observation

, the Shapley value of feature

is defined as follows:

Here, represents a subset of features excluding feature , denotes the model output predicted using only the feature subset , and the weighting term ensures fair contribution weighting across all possible feature permutations.

To further characterize the influence of individual features on model predictions, this study adopts the ALE method (

Apley & Zhu, 2020). Operating within the local-effects analytical framework for interpreting black-box models, the ALE approach addresses the extrapolation bias inherent in Partial Dependence Plots (PDPs) when features exhibit strong correlations. By doing so, it more accurately captures the genuine influence of features within their observed distributional ranges. In the univariate case, let

denote the target feature,

represent the other features of sample

, and

denote the model prediction function. The range of

is partitioned into

intervals

. The local effect is then computed as follows:

Here, denotes the centering constant that normalizes the mean of the ALE curve to zero, thereby facilitating its interpretation as deviations from a baseline reference. In addition, this study simultaneously estimated 95% confidence intervals during the ALE computation to quantify the uncertainty associated with the local effect estimates.

4. Data Sources and Processing

This study draws on data from the 2019 China Household Finance Survey (CHFS). The dataset covers 29 provinces (including autonomous regions and municipalities), 170 cities, 345 districts and counties, and 1360 village and neighborhood committees across China, comprising a total of 34,643 households. The sample is representative at both the national and provincial levels.

Following established literature, this study constructs 21 indicators across five dimensions to systematically examine the determinants of household participation in risky financial markets. The selection of variables is theory-driven and designed to capture distinct economic channels shaping household decision-making. Foundational characteristics represent life-cycle and family composition effects that influence liquidity needs and risk capacity. Wealth-related indicators reflect households’ ability to bear risk and their portfolio constraints. Measures of literacy capture information-processing capacity and human capital that facilitate understanding and management of financial products. Behavioral preference variables account for psychological, informational, and social factors that shape investment propensities. Finally, regional and institutional controls incorporate spatial heterogeneity in market access, financial infrastructure, and the broader economic environment.

Risky financial assets are defined to include stocks, funds, bonds, derivatives, financial wealth management products, foreign exchange, and gold. Households holding any of these assets are classified as participants in risky financial markets. Apart from questions that respondents were not required to answer, any observation containing missing values in the variables used for indicator construction was removed. To further mitigate the influence of extreme outliers, all continuous variables were winsorized at the 1st and 99th percentiles to reduce potential distortions arising from measurement errors. After these data-cleaning procedures, the final dataset consists of 25,336 valid observations. Descriptive statistics are reported in

Table 1.

In terms of foundational characteristics, the average age of household heads is approximately 55 years, and the sample is predominantly male. The dependency burden associated with elderly members substantially outweighs that of children, underscoring the mounting pressures of population aging. Regarding wealth status, nearly one-third of households carry debt, and both income distribution and property ownership exhibit significant disparities, with highly right-skewed and heavy-tailed distributions. In terms of behavioral preferences, risk tolerance and economic attention are generally concentrated at relatively low levels, suggesting a widespread tendency toward risk aversion and limited engagement with financial markets. Insurance participation is also skewed toward low-risk protection products, reinforcing the prevalence of conservative behavioral tendencies. With respect to literacy dimensions, educational attainment, financial literacy, and digital literacy are generally limited, indicating restricted information-processing capacity. Such limitations exacerbate cognitive barriers in navigating complex financial environments and further reduce the likelihood of engaging in risky asset allocation. Finally, regional characteristics reveal substantial heterogeneity in per capita GDP and digital financial inclusion across provinces, highlighting uneven accessibility of financial services and persistent market frictions, while household gift expenditure displays a highly right-skewed and heavy-tailed pattern, further illustrating extreme variability in social consumption behaviors.

5. Empirical Testing and Analysis

5.1. Forecasting Household Participation in Risky Financial Markets

We adopt three different training and testing partition schemes, namely 70:30, 80:20, and 90:10. For each scheme, hyperparameters are tuned on the training subset using grid search with five-fold cross-validation, and model performance is evaluated on the corresponding test subset. Across the four commonly used evaluation metrics, including ROC AUC, Accuracy, F1 Score, and Log Loss, all models exhibit strong predictive capability, yet the Random Forest model delivers the most balanced and reliable performance, as shown in

Table 2. Although the differences in ROC AUC are relatively small, Random Forest achieves higher Accuracy and F1 Scores and lower Log Loss values, indicating superior discrimination ability, probability calibration, and classification reliability. The model also demonstrates exceptional flexibility in capturing nonlinear relationships and feature interactions (

Choudhary et al., 2025), which further reinforces its robustness and reliability as a predictive algorithm. We ultimately select the 80:20 partition scheme because it provides an effective balance between adequate training information and reliable out-of-sample evaluation and is widely applied in the existing literature (

Joseph & Vakayil, 2022;

Rimal et al., 2024).

5.2. Key Drivers of Household Participation in Financial Markets

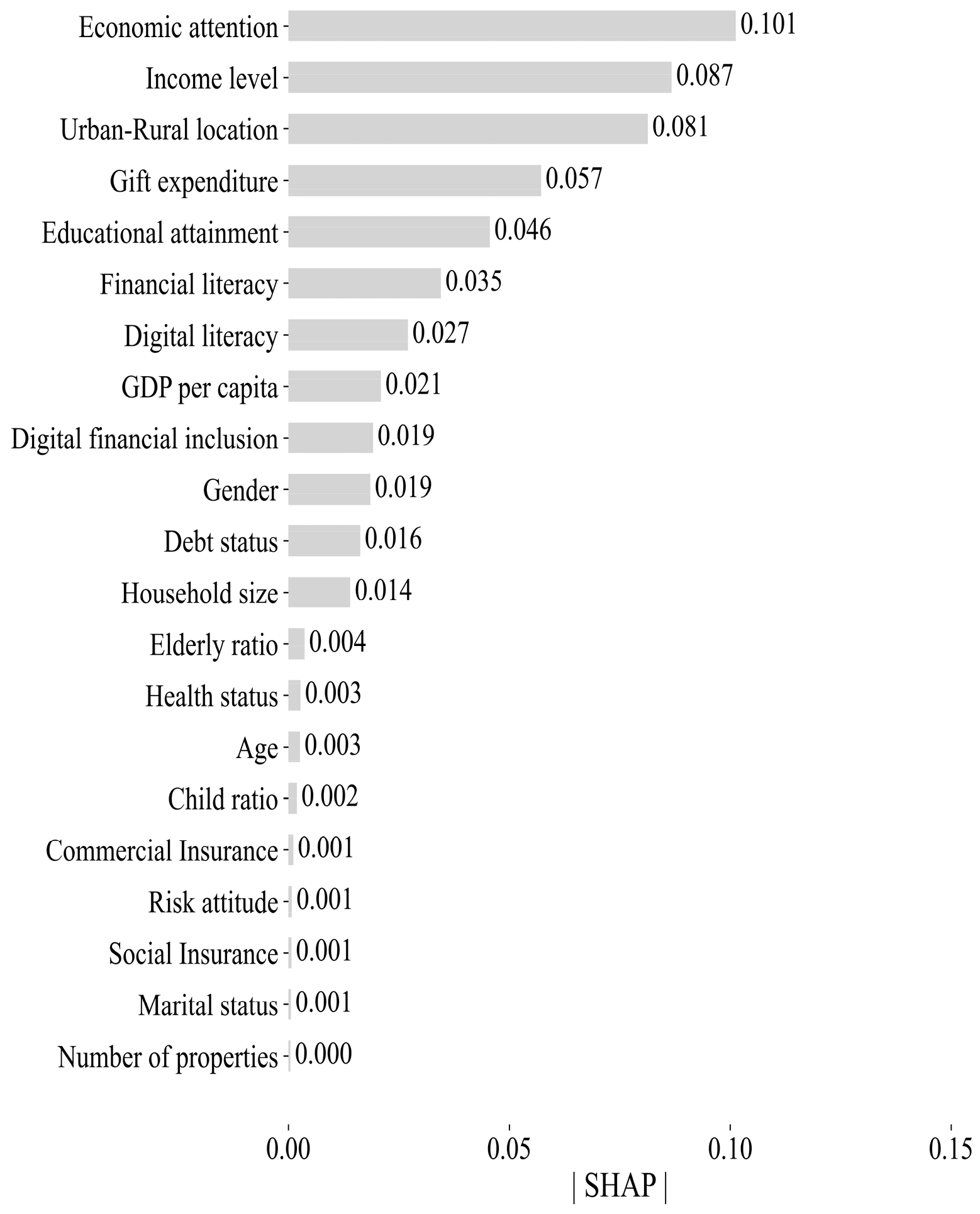

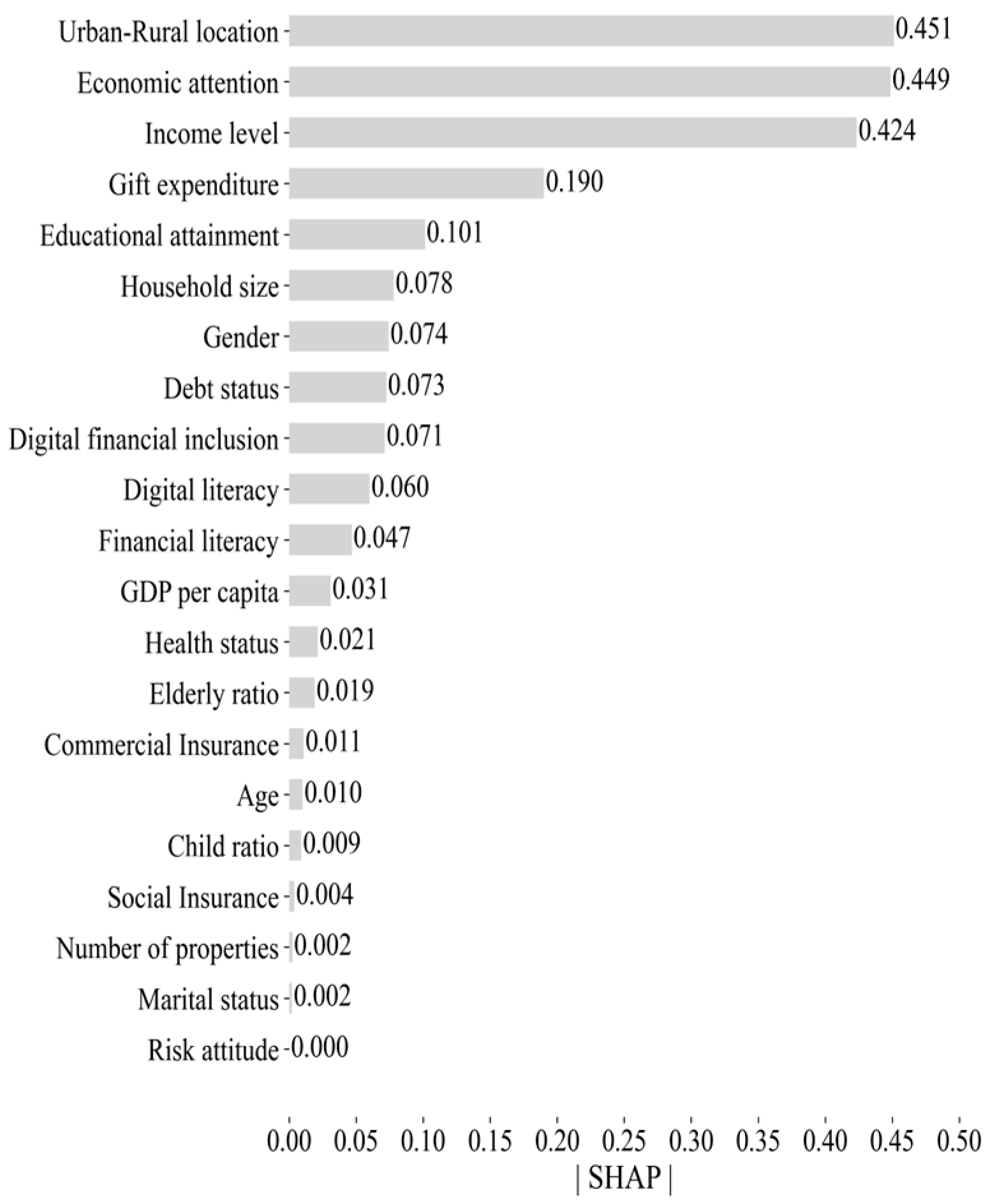

Results from the Random Forest model reveal that economic attention, income level, social interaction, educational attainment, and financial literacy are the primary determinants of household participation in risky financial markets, with all variables displaying nonlinear associations with participation outcomes. Low levels of these characteristics constitute major barriers to participation. As illustrated in

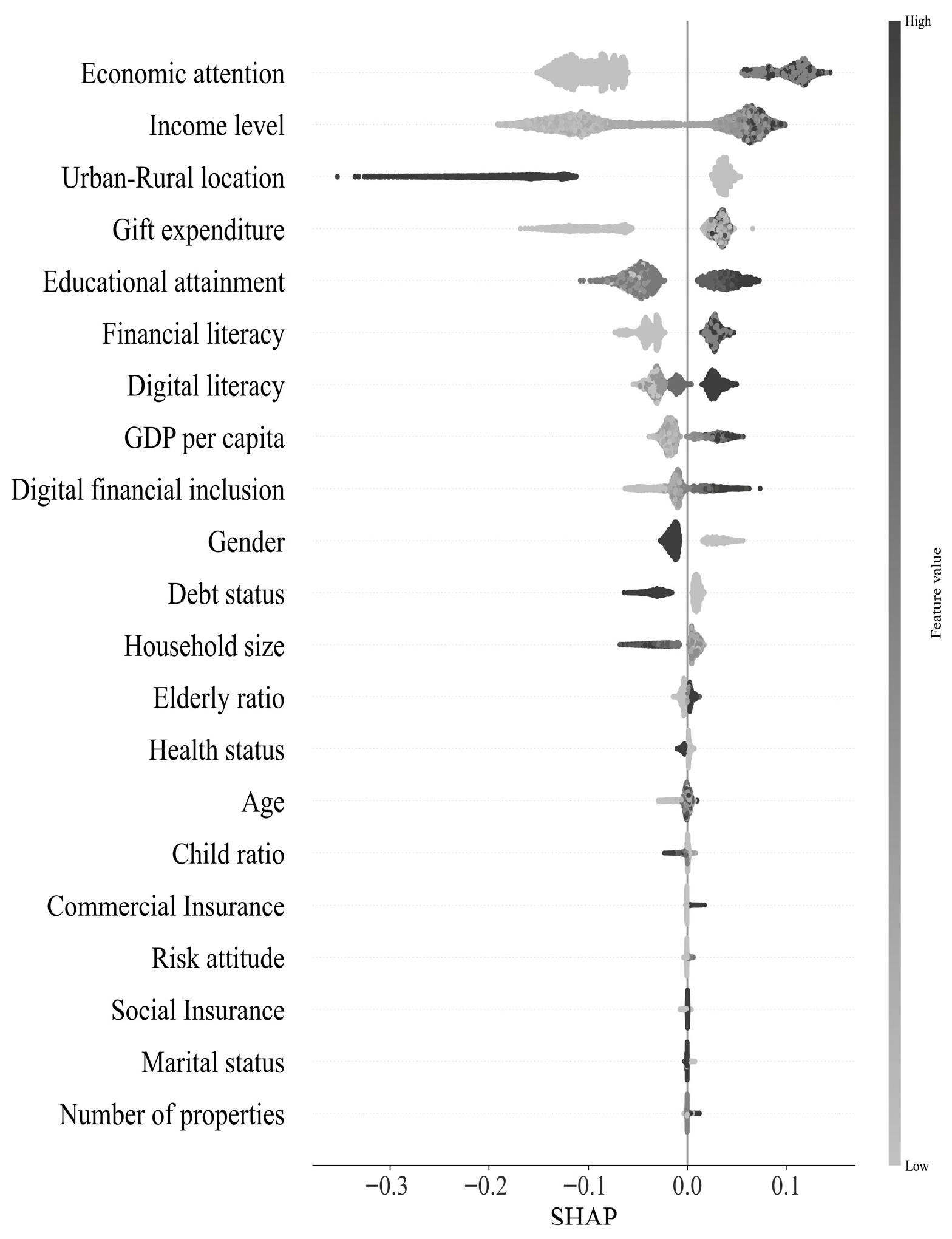

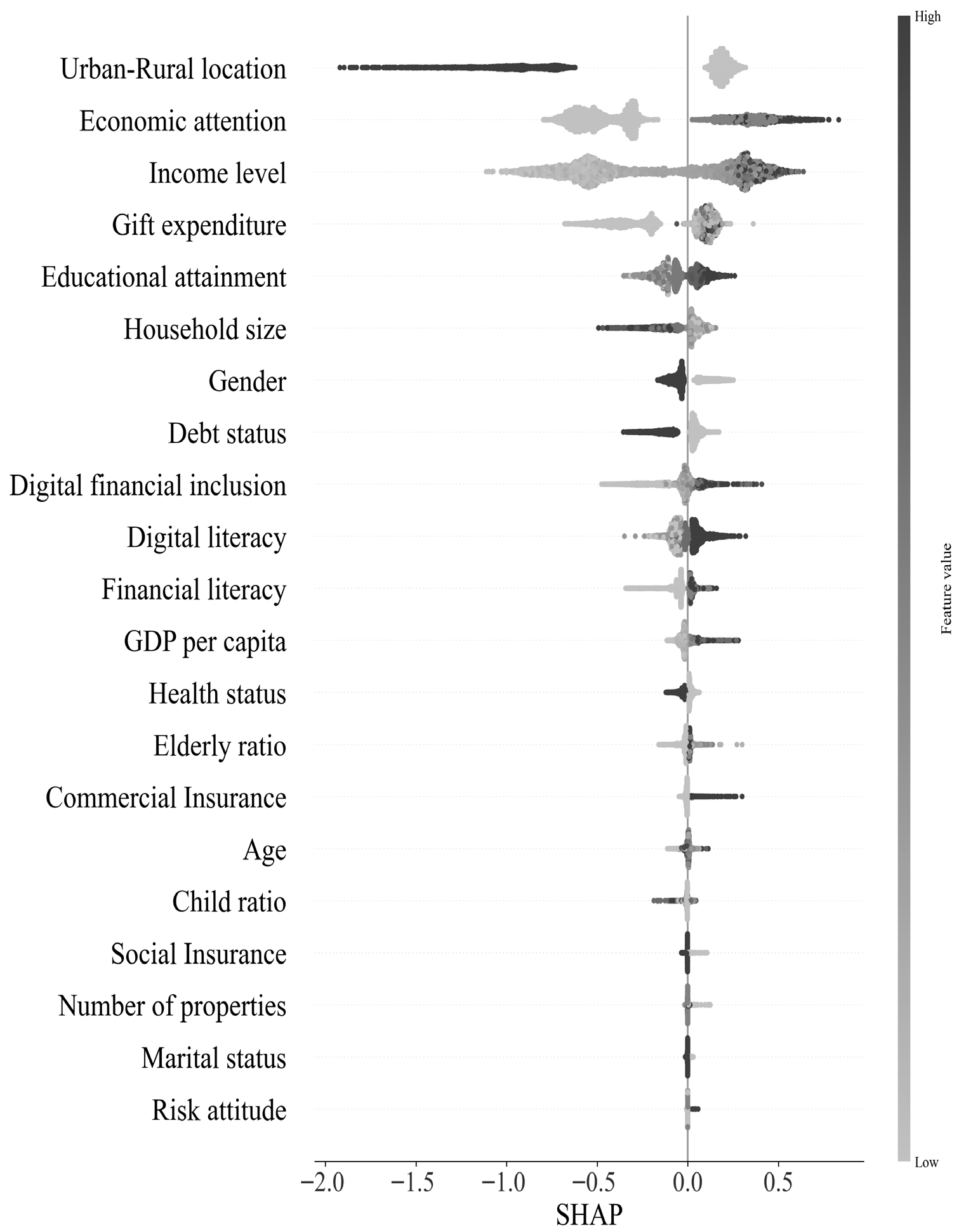

Figure 1, economic attention records the highest mean |SHAP| value, followed by income level and the urban–rural location, underscoring their dominant explanatory importance. Gift expenditure and financial literacy also exert substantial influence. Furthermore,

Figure 2 depicts the distribution of SHAP values across individual observations for each feature, where darker shading corresponds to higher feature values. This visualization highlights pronounced nonlinear relationships between predictors and participation probabilities.

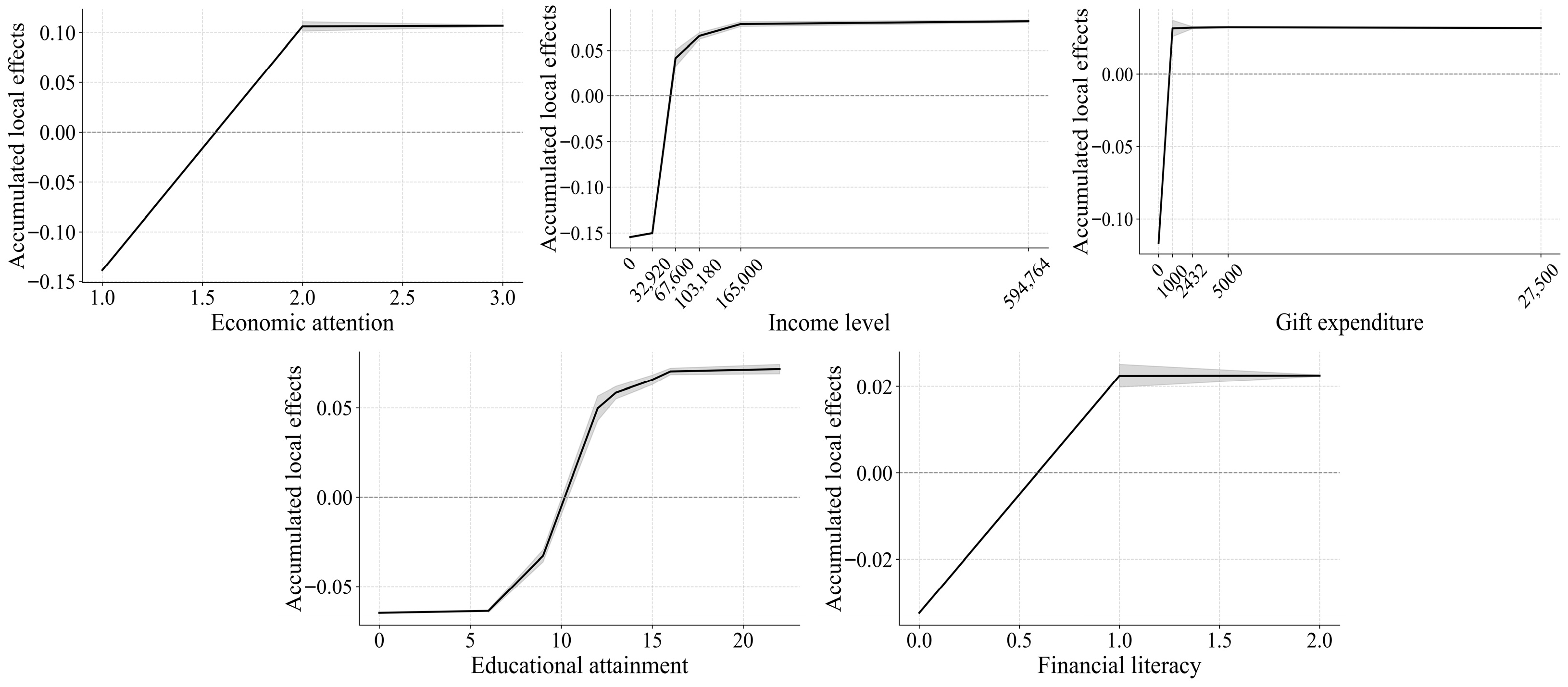

To further clarify the nonlinear effects of key predictors on household participation in risky financial markets, this study selected the top five continuous variables ranked by feature importance and generated their ALE plots (see

Figure 3). The gray shaded region indicates the 95% confidence interval surrounding the ALE estimates. The results demonstrate that economic attention, income level, gift expenditure, educational attainment, and financial literacy exhibit nonlinear patterns characterized by diminishing marginal effects following an initial positive association.

First, economic attention constitutes a fundamental behavioral factor reflecting households’ sensitivity to external economic conditions and investment propensity. Higher levels significantly enhance information acquisition and risk perception, thereby facilitating market participation. However, at elevated levels, the marginal effect declines sharply as investment demand approaches saturation. With an average score of only 1.34 across sampled households, economic attention remains generally low, representing a substantial barrier to engagement in risky financial markets.

Second, income level represents the primary dimension of background risk, determining the capacity to absorb potential losses. Higher income reduces precautionary saving motives and enables risk diversification through social networks. Yet beyond certain thresholds, the incentive to accumulate wealth through financial assets declines. With an average annual income of approximately ¥82,900 and considerable inequality in distribution, income growth remains a pivotal driver of participation.

Third, gift expenditure reflects the behavioral dimension of social interaction, promoting participation through information sharing and observational learning. However, excessive social engagement may induce herd behavior and diminish independent decision-making, thereby weakening marginal benefits. Notably, 38% of households reported zero expenditure in this category, indicating underdeveloped social networks that exacerbate limited participation.

Fourth, educational attainment serves as a central mechanism for enhancing information-processing capacity, promoting participation through improved financial literacy and optimized income structures. Nevertheless, the marginal benefits of additional schooling diminish as highly educated individuals face altered occupational risk preferences or greater family responsibilities. With an average of 9.69 years of schooling among household heads, significant scope for improvement persists.

Fifth, financial literacy extends information-processing capabilities by strengthening risk assessment and facilitating rational decision-making. Yet beyond a foundational threshold, its marginal influence diminishes gradually. The sample’s average score of only 0.63 underscores limited proficiency, significantly constraining household participation in risky financial markets.

5.3. Interaction Analysis of Factors Driving Household Financial Participation

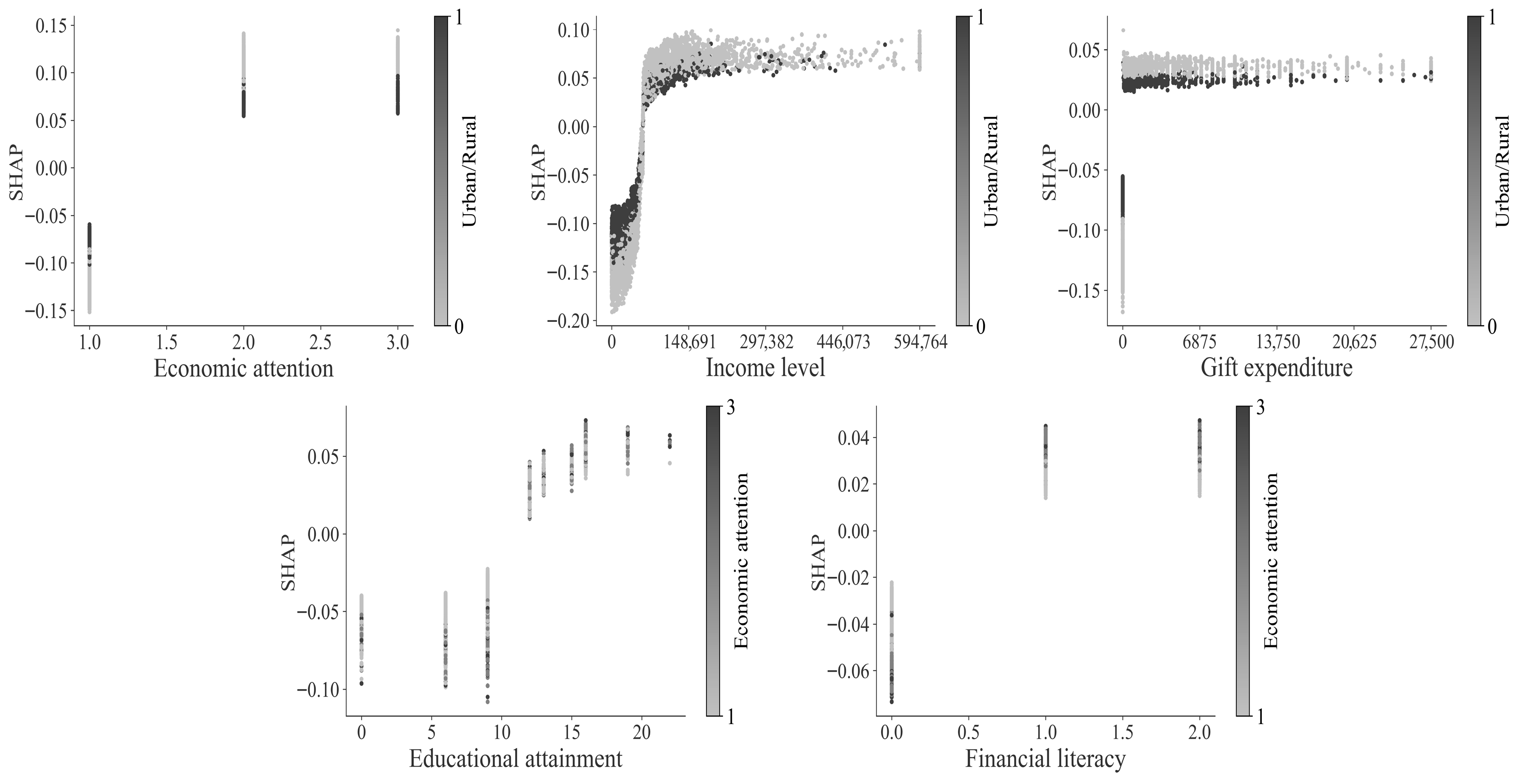

The interaction effect analysis reveals that limited participation in financial markets is driven not only by insufficient levels of individual characteristics but also by substantial feature–feature interactions. Variations in SHAP values for a given factor across households stem from both intrinsic heterogeneity in feature levels and their interdependencies with other variables. Leveraging SHAP’s interaction value algorithm, we calculate the pairwise interaction effects among all predictors. By visualizing these dependency structures, we uncover how one characteristic amplifies or mitigates the marginal effect of another.

Figure 4 illustrates the dependency plots for the five key features identified earlier: economic attention, income level, gift expenditure, educational attainment, and financial literacy, together with their strongest interaction counterparts.

Urban–rural location exhibits the strongest interaction effects with three key characteristics: economic attention, income level, and gift expenditure, displaying a reversal pattern across the urban–rural divide. First, at low levels of economic attention—which generally constrain participation in risky financial markets—urban households show lower participation rates than rural households. Conversely, at medium to high awareness levels that facilitate market entry, the positive effect is markedly stronger for urban households. This pattern suggests that urban households lacking economic attention face greater participation disadvantages than their rural counterparts, highlighting information attention as a prerequisite for realizing urban advantages.

Similarly, at lower income levels, urban households demonstrate weaker participation propensity compared with rural households. Only once income surpasses a certain threshold does the promotional effect for urban households become evident and subsequently stabilize, indicating that higher income is a critical condition for activating urban advantages. Finally, in the absence of social interaction, both urban and rural households exhibit constrained market participation, though the inhibitory effect is more pronounced for urban households. Once social interaction occurs, urban households’ willingness to participate rises sharply and eventually exceeds that of rural households. This indicates that social interaction also serves as a critical trigger for urban households’ participation.

Educational attainment and financial literacy exert the strongest moderating effects on economic attention, both functioning as threshold conditions. Specifically, heightened economic attention significantly increases market participation only when educational attainment exceeds twelve years—equivalent to completion of upper secondary education or higher. For individuals with lower educational levels, greater economic attention does not translate into substantial participation gains. This result indicates that information awareness must be underpinned by a sufficient educational foundation to be transformed into effective investment behavior. Similarly, the positive effect of economic attention is observed primarily among households with higher levels of financial literacy. In groups with limited financial literacy, increased attention may instead lead to misinterpretation and cognitive biases, thereby inhibiting participation. These findings underscore that mere exposure to economic information is insufficient to enhance engagement in risky financial markets; it must be complemented by adequate financial knowledge.

5.4. Analysis of Heterogeneity in Household Risk-Taking in Financial Markets

In addition to examining the determinants of household participation in risky financial markets for the overall sample, this study categorizes households into three age cohorts: young (18–44 years), middle-aged (45–59 years), and elderly (≥60 years), as well as two residential types: rural and urban. By analyzing these life-cycle stages in conjunction with urban–rural contexts, the study reveals how the underlying mechanisms of participation evolve dynamically across population segments. This heterogeneity analysis provides an empirical basis for designing more precisely targeted policy interventions.

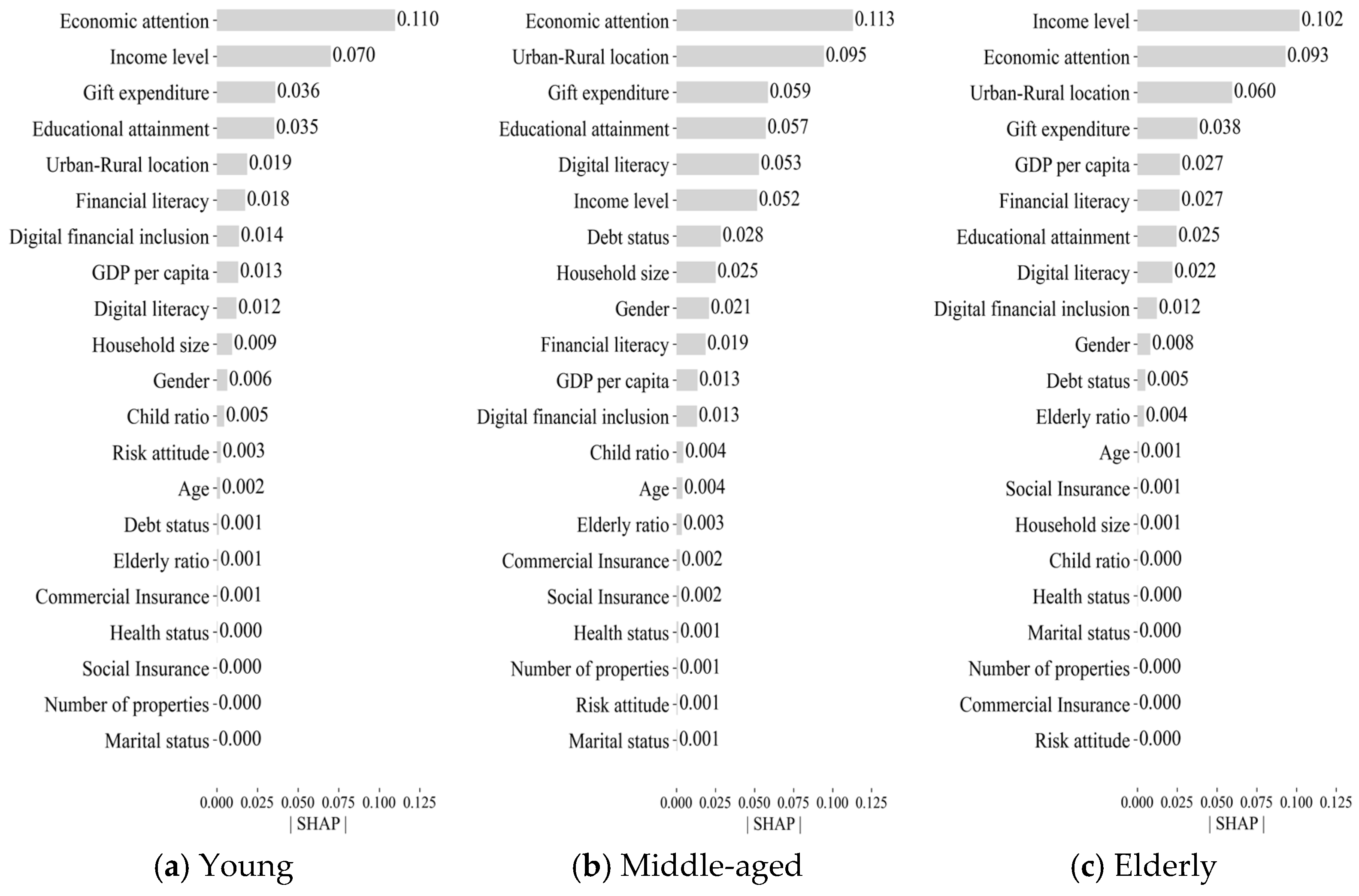

The results indicate that although the relative importance of influencing factors remains broadly consistent across household types, notable differences emerge in their resource dependencies and binding constraints. As illustrated in

Figure 5, participation in risky financial markets among young households is primarily driven by economic attention, income level, and social interaction, suggesting that their investment behavior is particularly sensitive to external information and relational dynamics. Importantly, urban–rural disparities exert relatively weaker effects on this group, implying that improvements in information infrastructure and financial inclusion policies are gradually narrowing the urban–rural gap among younger populations. In contrast, middle-aged households exhibit distinct patterns shaped by urban–rural location, digital literacy, and debt status. This cohort often faces the dual responsibilities of financing children’s education and providing support for elderly family members, with participation constrained by heightened financial pressures. Consequently, digital tools play a critical role in facilitating their investment decisions. Urban–rural disparities exert substantial influence on this group, reflecting persistent inequalities in regional resource allocation. For elderly households, income level, economic attention, and urban–rural differences constitute the primary determinants of participation. Inadequate income emerges as the central constraint, with rural elderly households particularly disadvantaged due to limited asset accumulation and weaker social security coverage. Although economic attention continues to shape investment propensity, generally low levels of financial literacy hinder the effective translation of information into concrete financial actions.

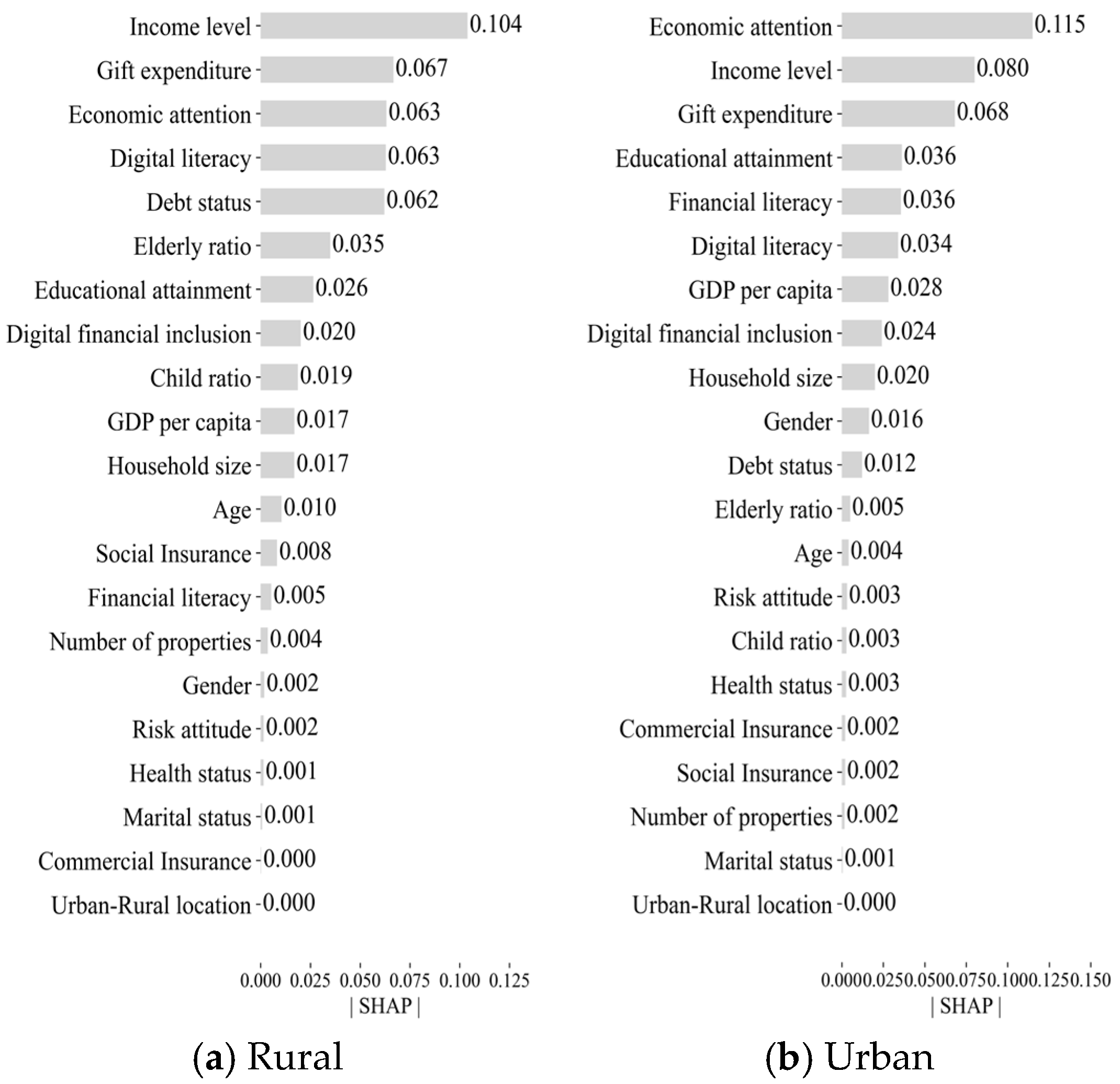

As illustrated in

Figure 6, rural households face primary constraints stemming from inadequate income and restricted credit access. Debt burdens exert markedly stronger effects on rural populations than on their urban counterparts, reflecting more severe liquidity shortages and repayment pressures. In addition, higher elderly dependency ratios and relatively underdeveloped pension security systems further limit investable resources, compelling households to prioritize basic living expenditures and eldercare responsibilities. In contrast, urban households’ participation is more strongly influenced by information access and cognitive capacity. Economic attention exerts a greater impact among urban populations, reflecting heightened sensitivity to macroeconomic conditions and market signals. Financial literacy also demonstrates stronger effects, as higher levels of financial capability enable urban households to more effectively transform information and cognitive resources into tangible investment behavior.

6. Econometric and Robustness Validation

6.1. Econometric Validation Using Probit Model

To enhance interpretability and validate the consistency of the machine learning results, a traditional Probit regression was estimated using the same explanatory variables as those applied in the machine learning models. The purpose of this analysis is to examine whether the signs and statistical significance of key predictors remain consistent under a conventional econometric specification. The dependent variable equals one if the household participates in risky financial markets and zero otherwise.

As shown in

Table 3, the signs and significance levels of key variables are highly consistent with the results derived from the machine learning models. In particular, income level, educational attainment, financial literacy, digital literacy, economic attention, and gift expenditure are all positively and significantly associated with household participation in risky financial markets, while urban–rural residence and debt status have significant negative effects. These results confirm that the machine learning models capture relationships that are aligned with traditional econometric inference, thus enhancing the interpretability and robustness of the findings.

To further examine the stability of the Probit estimation, multicollinearity was tested by computing variance inflation factors (VIF) based on an auxiliary OLS regression using the same set of explanatory variables. The results indicate that all VIF values are below the conventional threshold of 10, with an average VIF of 1.98. The two highest values correspond to per capita GDP (6.58) and the digital financial inclusion index (6.49), both within acceptable limits and not indicative of serious collinearity concerns. Therefore, the explanatory variables are considered sufficiently independent, ensuring the statistical reliability and robustness of the Probit estimates.

Beyond multicollinearity diagnostics, model stability was further examined by augmenting the Probit specification with the interaction terms highlighted by the SHAP-based machine-learning exploration. Specifically, interactions involving economic attention, urban–rural location, income, gift expenditure, educational attainment, and financial literacy were incorporated. Continuous variables were mean-centered prior to interaction construction to mitigate potential collinearity and enhance interpretability.

The main effects in Panel A of

Table 4 remain stable and consistent with those in

Table 3, indicating that introducing interaction terms does not substantively alter the estimated marginal impacts of the core predictors. Turning to the interaction terms (Panel B of

Table 4), two effects emerge as robust across both machine-learning and econometric approaches. First, the interaction between Economic attention and Urban–Rural location is negative and statistically significant at the highest level of economic attention. This indicates that increases in economic attention lead to a substantially greater rise in risky financial participation among urban residents relative to rural residents, consistent with the reversal pattern revealed by the machine-learning analysis. Second, the moderating role of Financial literacy is strongly supported. The interaction between economic attention and medium/high levels of financial literacy is positive and statistically significant, suggesting a clear threshold effect whereby economic attention translates into actual participation only when individuals possess adequate financial literacy.

The remaining interactions are statistically insignificant in the Probit specification. This pattern suggests that while machine-learning algorithms can detect weak predictive interactions, such patterns may not translate into statistically robust marginal effects in parametric models, consistent with methodological differences between predictive and inferential frameworks (

Pérez-Pons et al., 2022).

6.2. Robustness Checks with Alternative ML Specifications

This study employs two robustness validation strategies: (1) replacing the Random Forest model with XGBoost, and (2) substituting SHAP value rankings with the models’ intrinsic feature importance measures. XGBoost, grounded in the gradient boosting framework, offers a complementary methodological perspective for identifying key determinants relative to Random Forest. Moreover, tree-based learning algorithms quantify each feature’s contribution to improving node purity across all splits during training and evaluate its relative importance to overall predictions through weighted aggregation.

The robustness checks yield two principal findings. First, the SHAP value rankings and feature distributions exhibit substantial consistency between the XGBoost and Random Forest models, thereby reinforcing the reliability of the results.

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 present the SHAP values obtained from XGBoost predictions. Core variables—economic attention, income level, urban–rural location, gift expenditure, and educational attainment—retain high importance rankings across both models. Moreover, the nonlinear associations between feature values and SHAP outputs display notable stability across approaches. Second, modest variations emerge in relative importance weights: in XGBoost, urban–rural location rises to the highest rank, while financial literacy and digital capability decline in relative standing. In addition, XGBoost produces a more concentrated distribution of feature contributions, whereas Random Forest yields a comparatively balanced contribution profile.

Second, the internal feature importance ranking based on Gini impurity reduction demonstrates strong alignment with the SHAP-based rankings in identifying key predictors.

Table 5 reports the relative importance of features in the Random Forest model, as measured by mean decrease in impurity. The results show that economic attention remains the most influential factor, followed by household income level and urban–rural location. Moreover, the top ten features identified by this method are nearly identical to those derived from SHAP values, thereby providing additional confirmation of result robustness.

7. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

This study draws on data from the 2019 China Household Finance Survey (CHFS) to construct an analytical framework comprising 21 indicators across five dimensions: foundational characteristics, wealth status, comprehensive literacy, behavioral preferences, and regional development. Using both traditional Probit models and multiple machine learning approaches, we predict household participation in risky financial markets. The Random Forest model demonstrates superior performance across all evaluation metrics. More importantly, the machine learning approach provides novel insights that are difficult to obtain through traditional methods: (1) comprehensively comparing the relative contributions of different characteristics to household participation in risky financial markets; (2) identifying nonlinear patterns in important features and uncovering complex interaction mechanisms; and (3) examining heterogeneity in financial market participation across households at different life-cycle stages and geographical locations.

First, household participation is jointly constrained by multiple factors. Economic attention, income level, urban–rural location, gift expenditure, educational attainment, and financial literacy emerge as the primary predictors, all exhibiting nonlinear relationships with participation behavior. The generally low levels of these key characteristics among Chinese households constitute a fundamental driver of limited participation.

Second, substantial interaction effects exist among key variables. Urban–rural location interacts with economic attention, income, and social interaction through dual mechanisms of amplification and reversal. The advantages of urban households become evident only when economic attention surpasses certain thresholds, income reaches sufficient levels, and social interaction occurs with adequate frequency; otherwise, these advantages diminish or even reverse. Moreover, the positive influence of economic attention requires reinforcement from sufficient educational attainment and financial literacy. Without these foundations, awareness rarely translates into actual investment behavior.

Third, pronounced group heterogeneity exists across demographic segments. Younger households are more responsive to information availability and peer influence, with minimal constraints from urban–rural disparities. Middle-aged households are primarily constrained by debt burdens, which reduce their capacity to assume financial risk. Elderly households face limitations stemming from single income sources and inadequate information-processing capacity. Regarding residential differences, rural households exhibit significantly lower participation rates than urban households, largely due to tighter financial constraints, lower financial literacy, and heavier pension burdens.

These findings carry several implications for policymakers and financial practitioners seeking to broaden market participation, mitigate behavioral frictions, and strengthen household financial risk management. Enhancing educational attainment and financial literacy constitutes a fundamental pathway for expanding engagement, as these factors provide the necessary foundation for economic attention to translate into investment behavior. Multi-level financial education programs, particularly targeting rural, middle-aged, and elderly populations, should be prioritized, with collaborations among local governments, educational institutions, and financial organizations ensuring accessible and tailored training.

Reducing information asymmetry and fostering economic attention are also critical. Government-led media initiatives and digital financial inclusion platforms can disseminate timely, comprehensible financial information, particularly to rural and low-income households, thereby lowering cognitive and psychological barriers to participation.

Moreover, social networks and financial intermediaries play a pivotal role in converting awareness into actual investment decisions. Community-based investment platforms, peer learning groups, and professional advisory services can promote rational investment behavior while mitigating herd effects. Financial institutions are encouraged to provide transparent and personalized investment counseling to address the diverse needs of households.

Finally, policy design should reflect demographic and regional heterogeneity. For middle-aged households, reforms in credit and debt management can alleviate liquidity constraints and enhance risk-taking capacity. For elderly households, the development of diversified retirement financial products and improved pension systems can expand participation channels. Continued investment in digital financial infrastructure is essential to narrowing urban–rural disparities and ensuring equitable access to financial services.

As future research directions, we suggest that scholars consider extending this framework by incorporating longitudinal or panel data to capture the temporal evolution of household financial behaviors and to better identify potential causal relationships. Future studies may also deepen the interpretability of machine learning models by integrating them with complementary statistical inference approaches, which could provide richer insights into subgroup heterogeneity and behavioral mechanisms. Moreover, expanding the analytical framework to include regional institutional factors or behavioral indicators would allow for a more comprehensive understanding of how policy environments and cognitive characteristics jointly influence financial participation. Finally, applying this methodology to cross-country or multi-period datasets could offer valuable comparative perspectives and further validate the robustness and generalizability of the findings.