Dynamic Asset Allocation for Pension Funds: A Stochastic Control Approach Using the Heston Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Methodology

3.1. Heston Stochastic Volatility Model and Problem Formulation

3.2. Solution Method and Numerical Scheme

4. Empirical Implementation: Calibration and Data

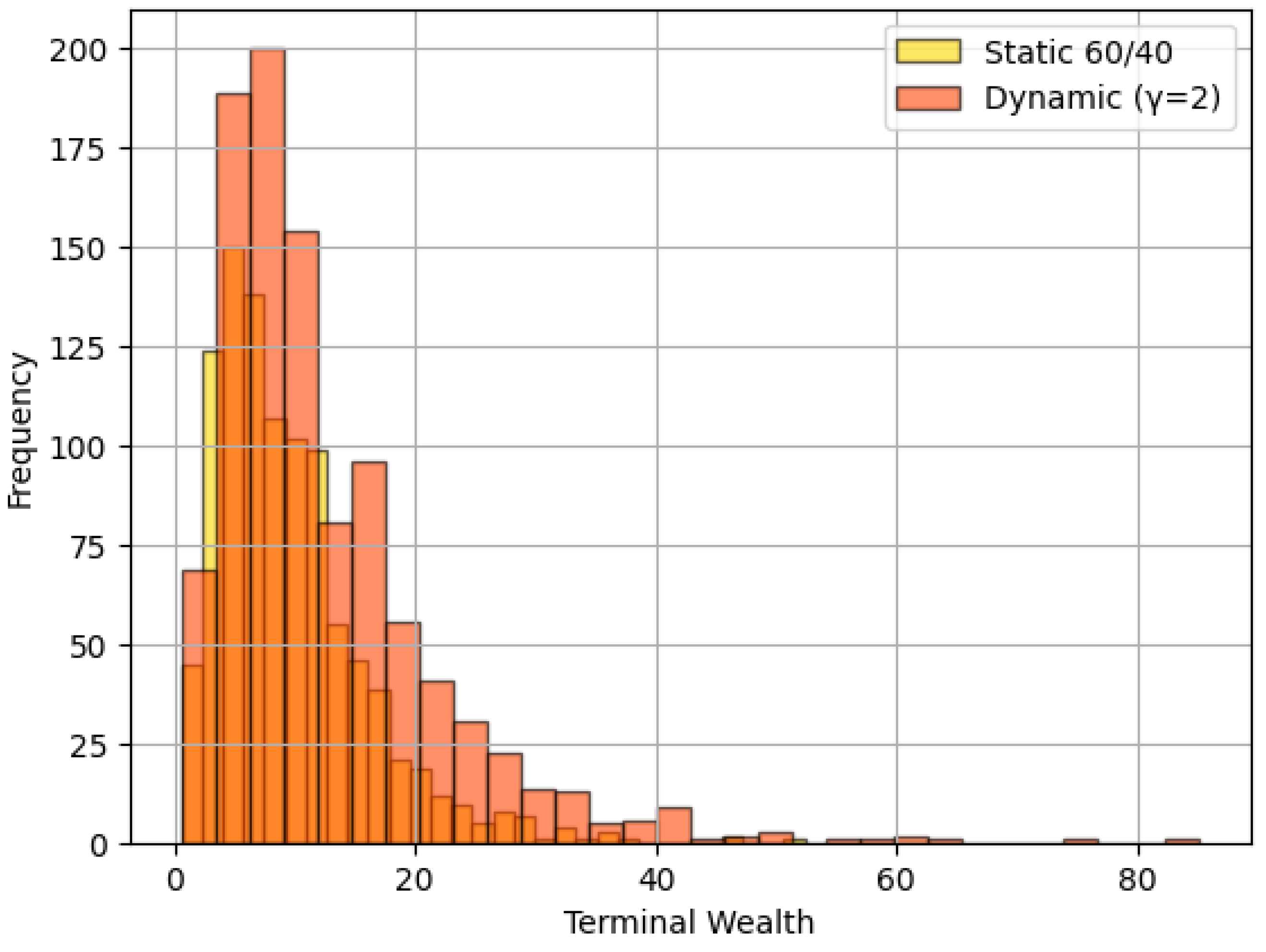

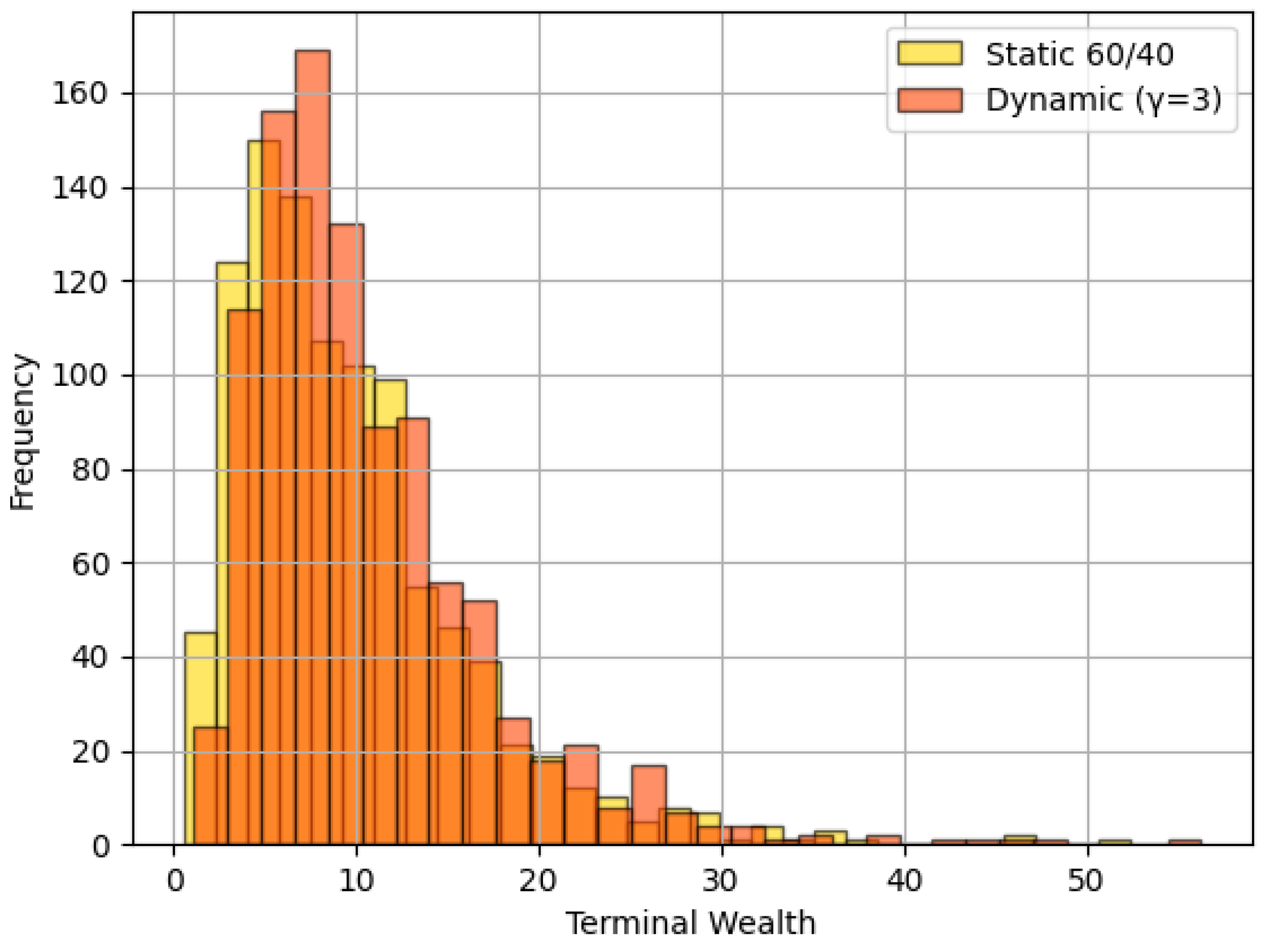

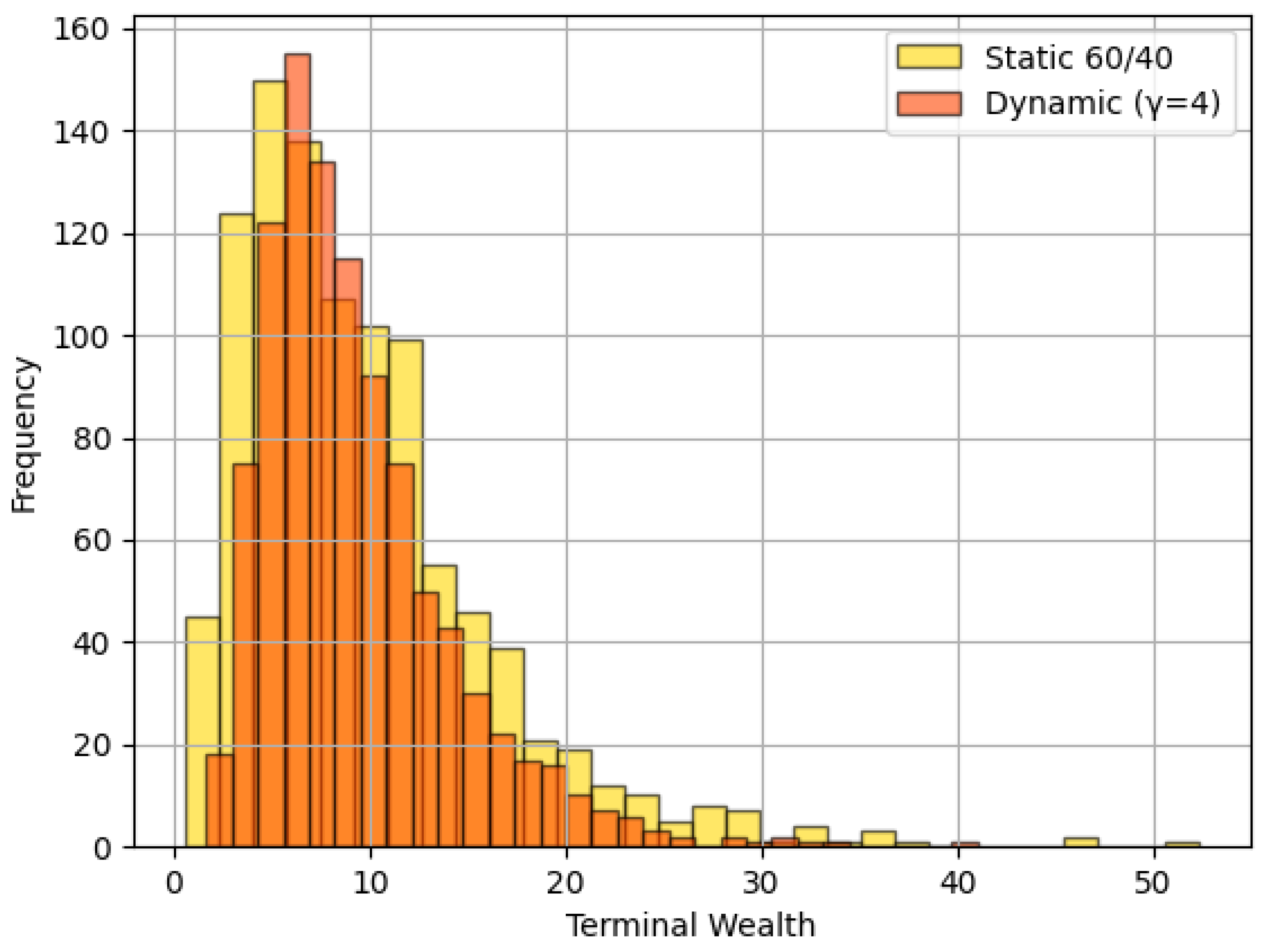

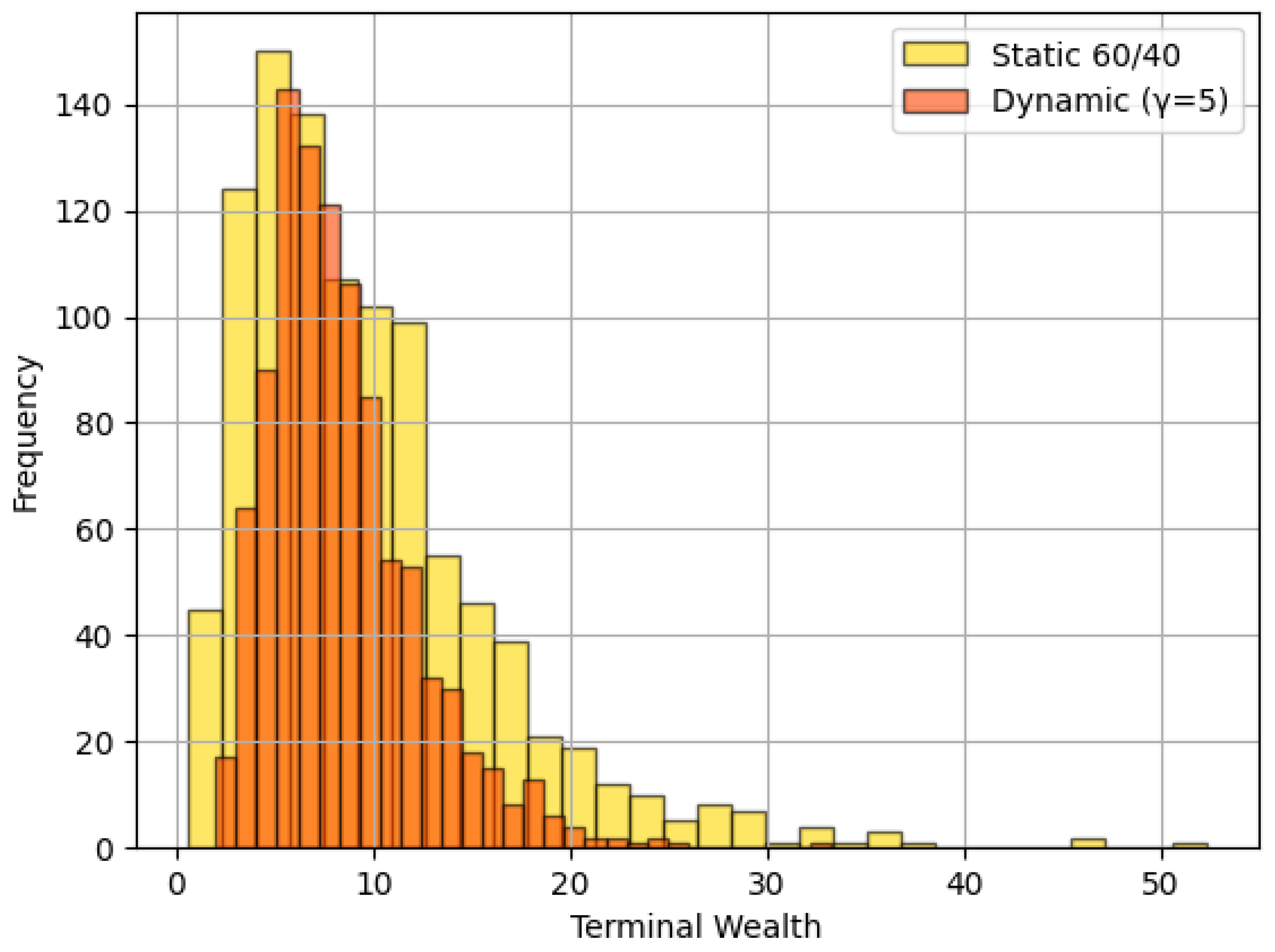

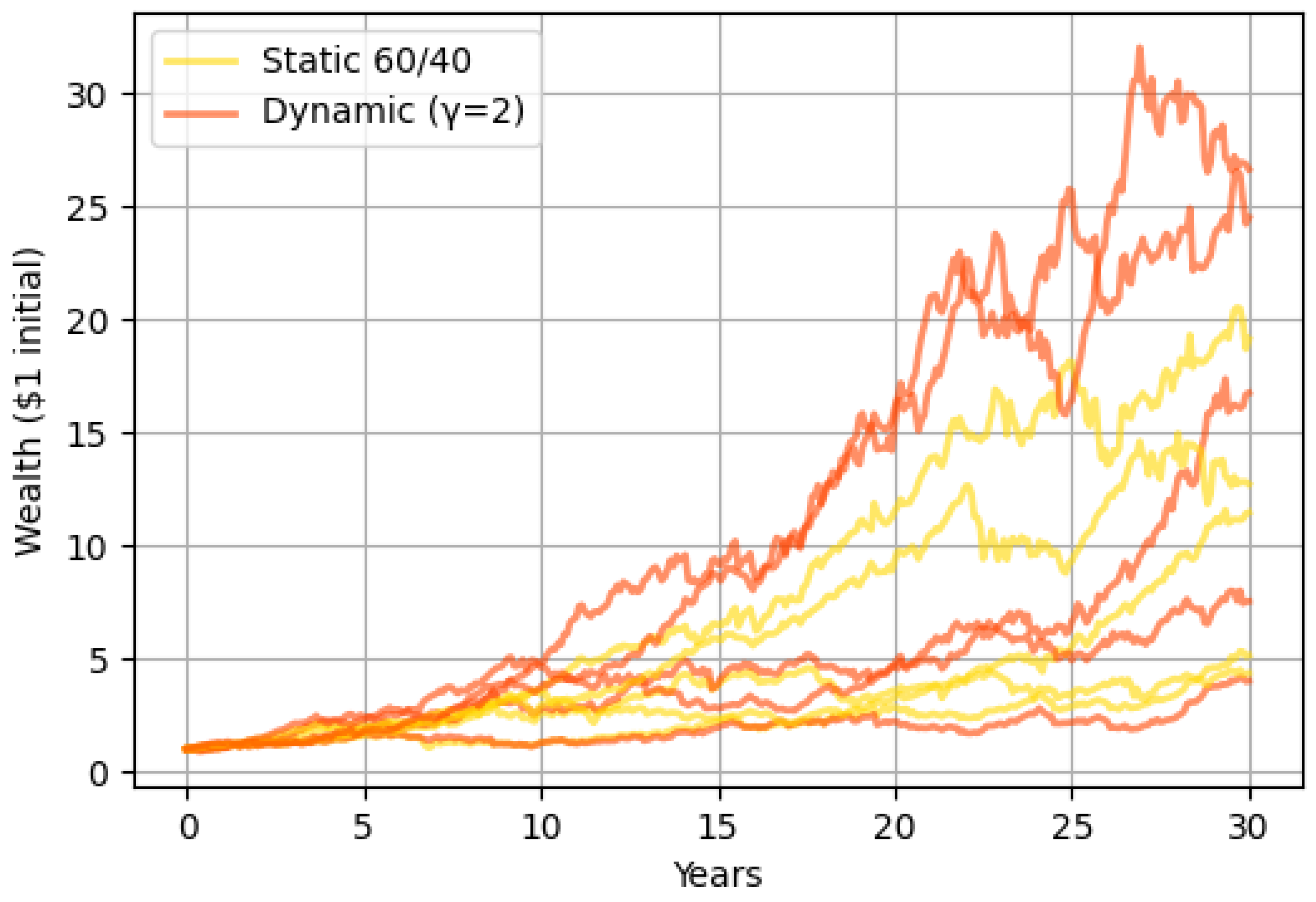

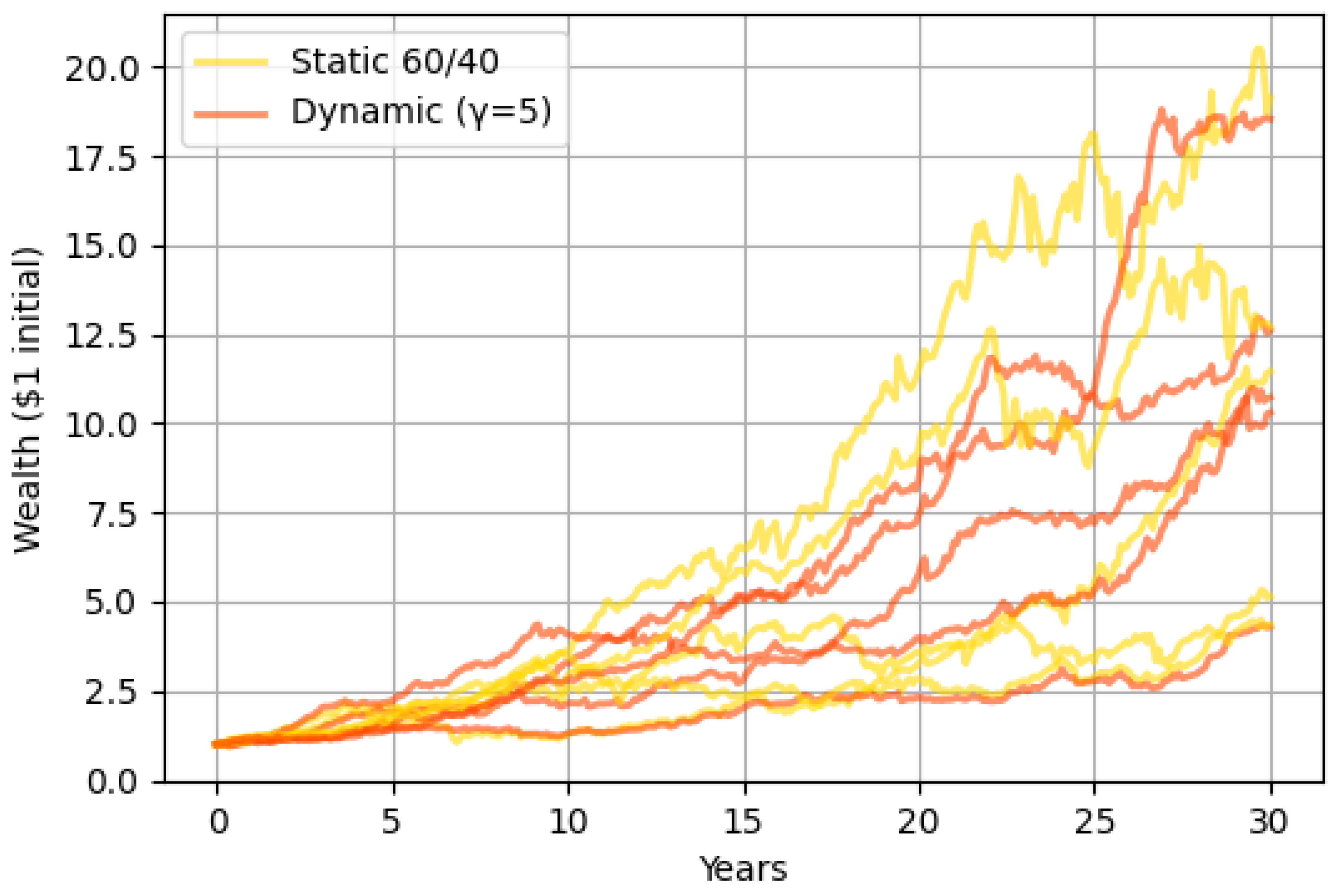

5. Simulation Results and Performance Analysis

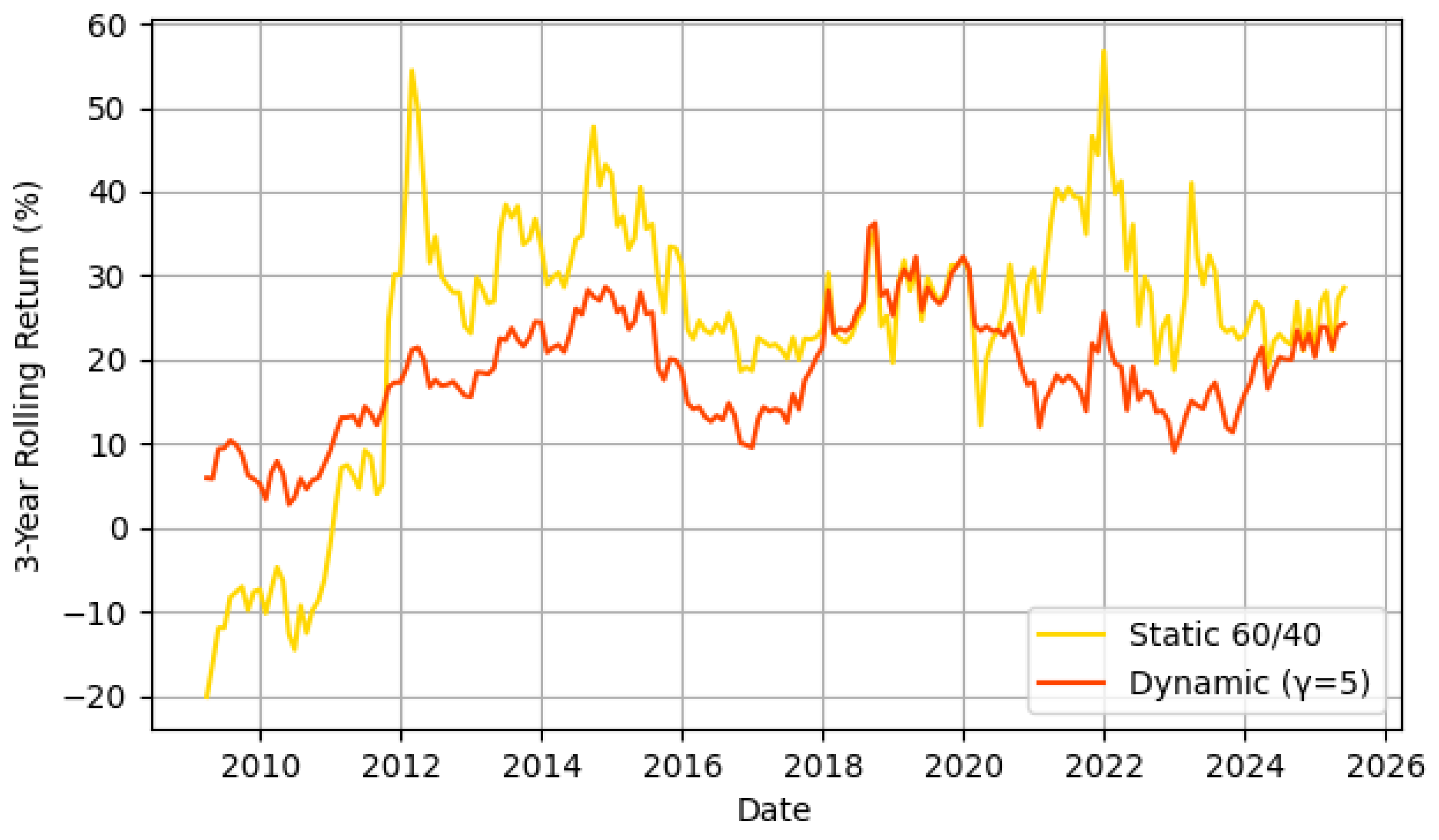

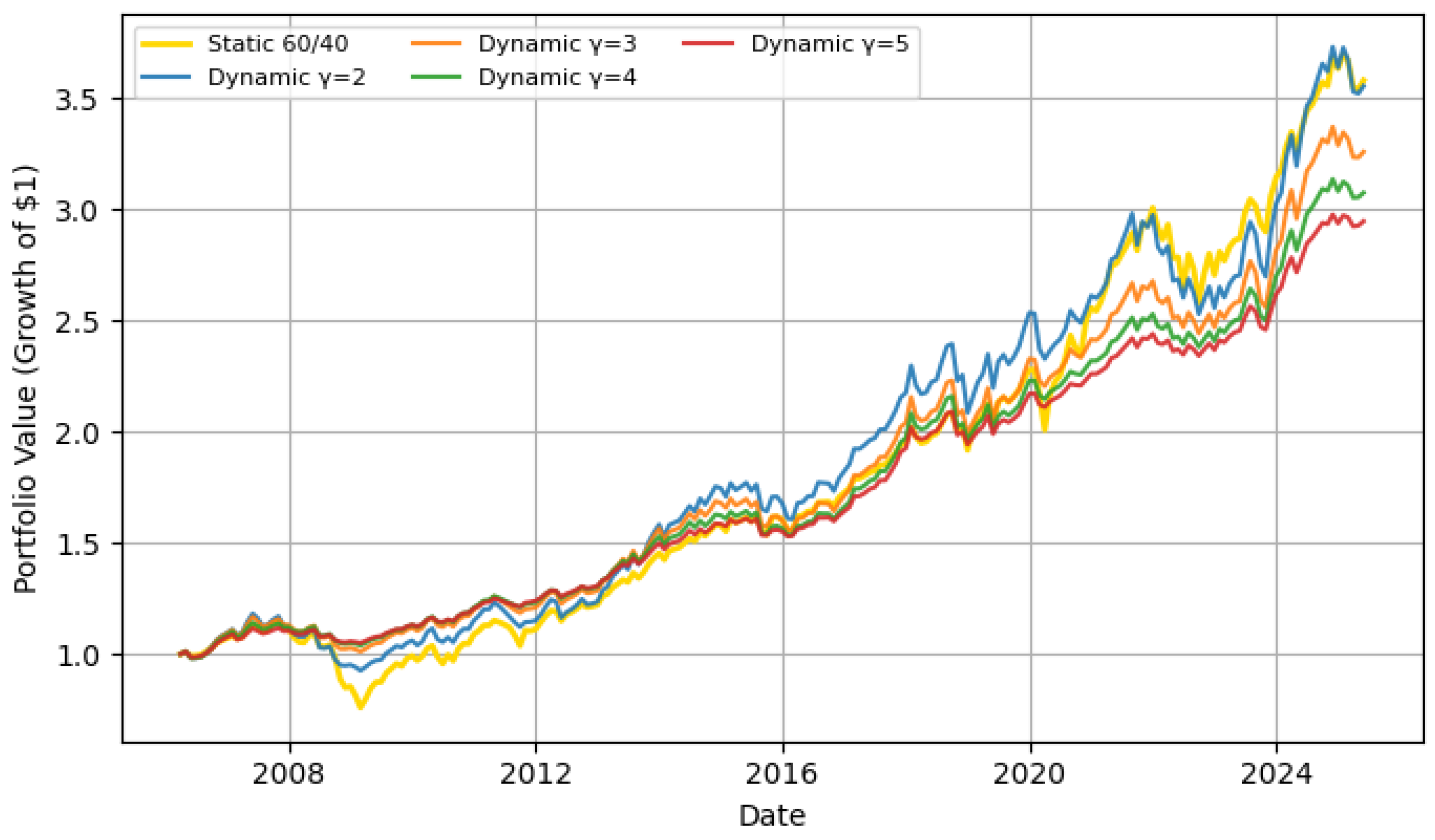

- Dynamic Strategy: Follows as computed. This is implemented by rebalancing the portfolio continuously (or at fine discrete intervals) according to the current . In practice, one could rebalance monthly or when volatility moves significantly.

- Static 60/40 Strategy: Maintains in equities and in bonds throughout (rebalanced periodically to maintain this mix).

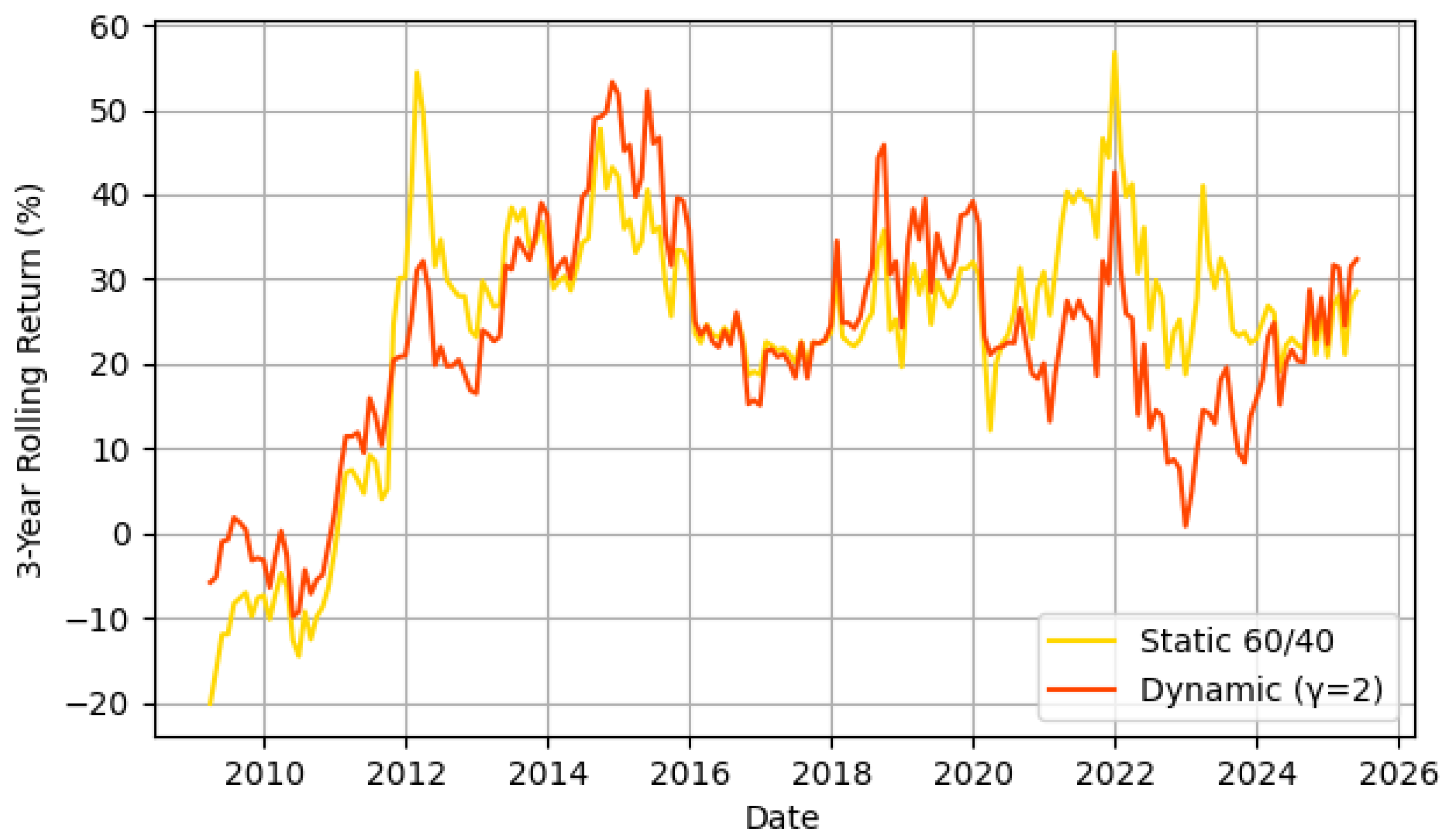

Backtest March 2006 to April 2025

6. Discussion

6.1. Performance Comparison and Risk Trade-Offs

6.2. Transaction Costs and Implementation Feasibility

6.3. Robustness to Estimation Noise

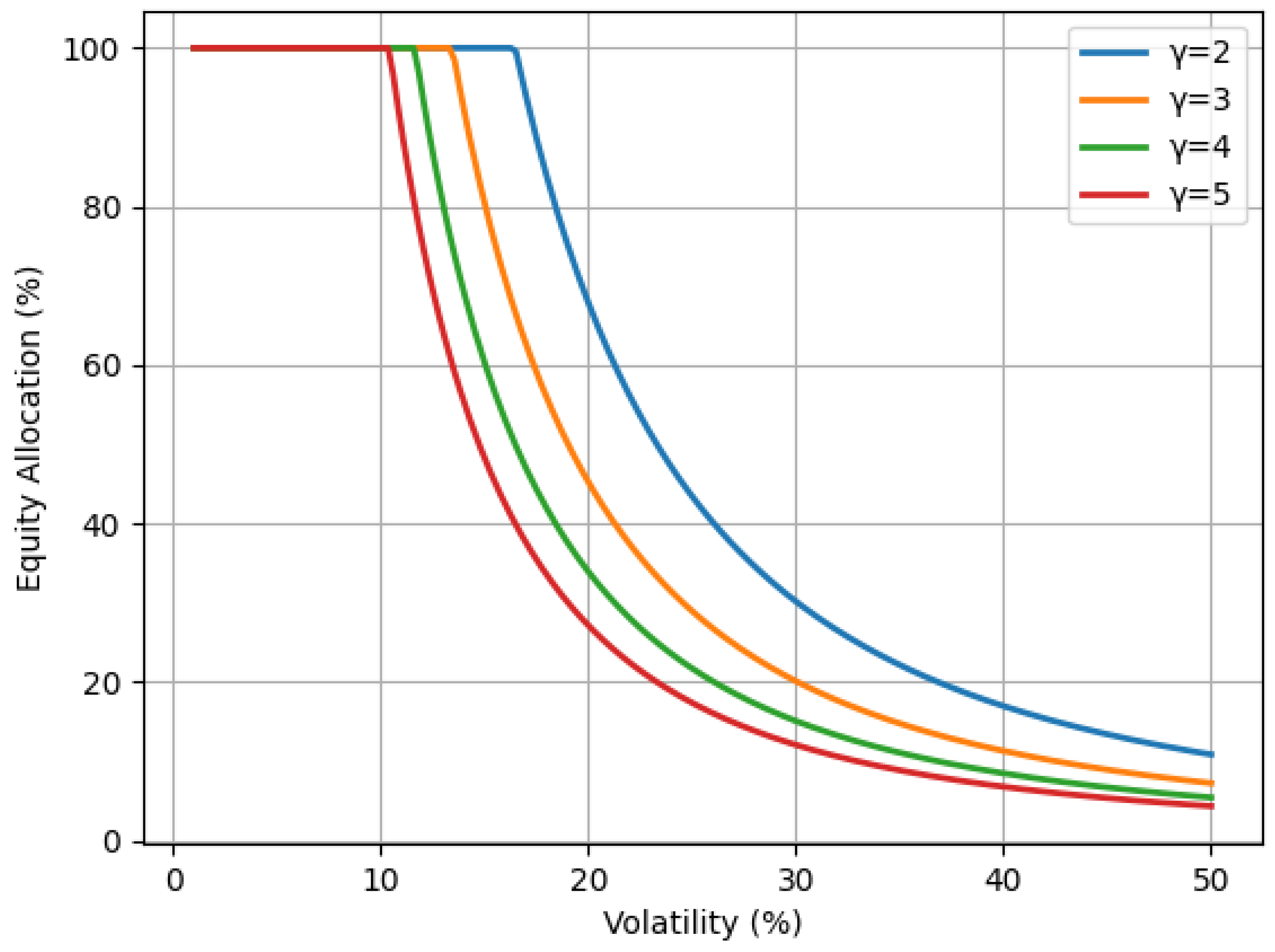

6.4. Volatility-Driven Allocation and Risk Management

6.5. Implications for Long-Term Investors

6.6. Practical Viability and Future Research

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arouri, M., Mayssa, M., & Shahrour, M. H. (2025). Dynamic connectedness and hedging effectiveness between green bonds, ESG indices, and traditional assets. European Financial Management. early view. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahaji, M., & Aberkane, S. (2016). Modeling VIX futures using a two-factor stochastic volatility framework. Economic Modelling, 52, 429–433. [Google Scholar]

- Bollerslev, T., Chou, R. Y., & Kroner, K. F. (1992). ARCH modeling in finance: A review of the theory and empirical evidence. Journal of Econometrics, 52(1–2), 5–59. [Google Scholar]

- Boulier, J.-F., Huang, S. J., & Taillard, G. (2001). Optimal management under stochastic interest rates: The case of a protected defined contribution pension fund. Insurance: Mathematics and Economics, 28(2), 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, M. J., & Xia, Y. (2002). Dynamic asset allocation under inflation. The Journal of Finance, 57(3), 1201–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairns, A. J. G., Blake, D., & Dowd, K. (2006). Stochastic lifestyling: Optimal dynamic asset allocation for defined contribution pension plans. Journal of Economic Dynamics & Control, 30(5), 843–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J. Y., & Hentschel, L. (1992). No news is good news: An asymmetric model of changing volatility in stock returns. Journal of Financial Economics, 31(3), 281–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CBOE. (2022). Understanding the relationship between the S&P 500 and the VIX. In CBOE insights (pp. 291–293). CBOE. [Google Scholar]

- Chacko, G., & Viceira, L. M. (2005). Dynamic consumption and portfolio choice with stochastic volatility in incomplete markets. The Review of Financial Studies, 18(4), 1369–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P., Yang, H. L., & Yin, G. (2008). Markowitz’s mean-variance asset-liability management with regime switching: A continuous-time model. Insurance: Mathematics and Economics, 18(1), 456–465. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, C. M., & Li, D. (2006). Asset and liability management under a continuous-time mean-variance optimization framework. Insurance: Mathematics and Economics, 39(3), 330–355. [Google Scholar]

- Chow, T.-m., Hsu, J., Kuo, L.-l., & Li, F. (2014). A study of low-volatility portfolioconstruction methods. The Journal of Portfolio Management, 40(4), 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvitanic, J., Lazrak, A., Martellini, L., & Zapatero, F. (2003). Optimal allocation to hedge funds: An empirical analysis. Quantitative Finance, 3(1), 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deelstra, G., Grasselli, M., & Koehl, P.-F. (2003). Optimal investment strategies in the presence of a minimum guarantee. Insurance, 33, 189–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, W. H., & Hernández-Hernández, D. (2003). An optimal consumption model with stochastic volatility. Finance and Stochastics, 7(2), 245–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, P. A., & Vetzal, K. R. (2017). Dynamic mean–variance asset allocation: Tests for robustness. International Journal of Financial Engineering, 19(6), 989–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, K. R., Schwert, G. W., & Stambaugh, R. F. (1987). Expected stock returns and volatility. Journal of Financial Economics, 19, 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J. (2008). Stochastic optimal control of DC pension funds. Insurance: Mathematics and Economics, 42(3), 1159–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Investment Company Institute. (n.d.). Statistical report. Available online: https://www.ici.org/statistical-report (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Investopedia. (2023). What the VIX tells us about market volatility (pp. 430–434). Investopedia. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, B. A., & Sørensen, C. (2001). Paying for minimum interest guarantees: Who should compensate whom? European Financial Management, 7(2), 183–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandhari, J., & Morgan Stanley Investment Management. (2024). Return of the 60/40: big picture macro insight. Morgan Stanley Investment Management. Available online: https://www.morganstanley.com/im/publication/insights/articles/article_bigpicturereturnofthe6040_ltr.pdf (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Keel, A., & Müller, H. (1995). Efficient portfolios in the asset liability context. ASTIN Bulletin, 25(1), 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T. S., & Omberg, E. (1996). Dynamic nonmyopic portfolio behavior. The Review of Financial Studies, 9(1), 141–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraft, H. (2005). Optimal portfolios and Heston’s stochastic volatility model: An explicit solution for power utility. Quantitative Finance, 5(3), 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leippold, M., Trojani, F., & Vanini, P. (2004). A geometric approach to multi-period mean variance optimization of assets and liabilities. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 28(6), 1079–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., & Chen, X. (2025). Return–volatility dynamics and volatility index forecasting: Evidence from the U.S. market. Journal of Futures Markets, 45(2), 241–244. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J. (2007). Portfolio selection in stochastic environments. Review of Financial Studies, 20(1), 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macroption. (2022). S&P 500 and VIX correlation: Historical relationship explained (pp. 80–82). Macroption Analytics Blog. [Google Scholar]

- Merton, R. C. (1969). Lifetime portfolio selection under uncertainty: The continuous-time case. Review of Economics and Statistics, 51(3), 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resonanz Capital. (2025). Beyond the mean: Rethinking diversification in the regime shift era. Resonanz Capital GmbH. Available online: https://resonanzcapital.com/insights/beyond-the-mean-rethinking-diversification-in-the-regime-shift-era (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Shahrour, M. H. (2022). Measuring the financial and social performance of French mutual funds: A data envelopment analysis approach. Business Ethics, the Environment & Responsibility, 31(2), 398–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, W. F., & Tint, L. G. (1990). Liabilities—A new approach. Journal of Portfolio Management, 16(2), 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S. X., Li, Z. F., & Wang, S. Y. (2008). Continuous-time portfolio selection with liability: Mean-variance model and stochastic LQ approach. Insurance: Mathematics and Economics, 42(3), 943–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zariphopoulou, T. (2001). A solution approach to valuation with unhedgeable risks. Finance and Stochastics, 5(1), 61–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X., & Taksar, M. (2012). A stochastic volatility model and optimal portfolio selection. Quantitative Finance, 13(10), 1547–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Interpretation | Value (Baseline) |

|---|---|---|

| r | Risk-free interest rate | 0.0437 (4.37% p.a.) |

| Expected stock return | 0.098 (9.8% p.a.) | |

| Equity risk premium | 0.05 (5% p.a.) | |

| Volatility mean-reversion speed | 3 (annual) | |

| Long-run variance | 0.04 (i.e., 20% vol) | |

| Volatility of volatility | 0.50 | |

| Correlation (returns, vol) | −0.7 | |

| Initial variance | 0.04 (20% initial vol) |

| Strategy | Total Return (%) | Final Wealth | Ann. Return (%) | Ann. Vol. (%) | Worst 12 m Loss (%) | Best 12 m Gain (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Static 60/40 | 258.02 | 3.580 | 6.88 | 9.19 | −27.97 | 32.30 |

| Dynamic | 255.47 | 3.555 | 6.84 | 9.30 | −18.86 | 34.18 |

| Dynamic | 225.80 | 3.258 | 6.36 | 7.31 | −11.59 | 28.91 |

| Dynamic | 207.42 | 3.074 | 6.03 | 5.85 | −7.77 | 23.71 |

| Dynamic | 194.63 | 2.946 | 5.80 | 4.74 | −5.61 | 21.59 |

| Strategy | Sharpe Ratio | CER (%) | Max Drawdown (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Static 60/40 | 0.28 | 6.80 | 36.4 |

| Vol-Target | 0.35 | 7.28 | 24.7 |

| CPPI | 0.27 | 7.53 | 51.7 |

| Dynamic () | 0.34 | 7.64 | 29.9 |

| Dynamic () | 0.35 | 7.32 | 21.8 |

| Dynamic () | 0.36 | 7.02 | 17.1 |

| Dynamic () | 0.37 | 6.78 | 14.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marozva, D.; Gherghina, Ş.C. Dynamic Asset Allocation for Pension Funds: A Stochastic Control Approach Using the Heston Model. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 640. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18110640

Marozva D, Gherghina ŞC. Dynamic Asset Allocation for Pension Funds: A Stochastic Control Approach Using the Heston Model. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(11):640. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18110640

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarozva, Desmond, and Ştefan Cristian Gherghina. 2025. "Dynamic Asset Allocation for Pension Funds: A Stochastic Control Approach Using the Heston Model" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 11: 640. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18110640

APA StyleMarozva, D., & Gherghina, Ş. C. (2025). Dynamic Asset Allocation for Pension Funds: A Stochastic Control Approach Using the Heston Model. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(11), 640. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18110640