Financing Rural Futures: Governance and Contextual Challenges of Village Fund Management in Underdeveloped Regions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainable Rural Development and the Role of Decentralization

2.2. The Village Fund Policy in Indonesia

2.3. Key Governance Concepts Relevant to Village Fund Management

2.4. Theoretical Perspectives, Research Propositions, and Research Questions

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Methods

- Regional Topography: Mountainous (villages in Papua Pegunungan Province and other highland regencies) vs. coastal (villages with direct sea access).

- Natural Resource Endowment: Classified using a resource endowment classification score constructed from four binary indicators that reflect the presence of major commercial activities (mining, plantation, forestry, and fishing). Thresholds: Villages with a score of ≥1 (indicating at least one major commercial activity) were classified as resource-rich; villages with a score of =0 (indicating reliance primarily on subsistence activities) were classified as resource-poor.

- Transport Accessibility: Easy access (year-round four-wheel road connectivity) vs. difficult access (dependent on river, sea, or air transport).

- Population Structure: Indigenous Majority (≥50% Original Papuan People) vs. Migrant Majority (<50%).

4. Results

4.1. Respondent Profile

4.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis

4.3. Measurement Model Analysis

4.4. Structural Model Analysis

4.5. Multi-Group Analysis (MGA)

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Akbar, A., Flacke, J., Martinez, J., & van Maarseveen, M. F. A. M. (2020). Participatory planning practice in rural Indonesia: A sustainable development goals-based evaluation. Community Development, 51(3), 243–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akita, T., Riadi, A. A., & Rizal, A. (2021). Fiscal disparities in Indonesia in the decentralization era: Does general allocation fund equalize fiscal revenues? Regional Science Policy & Practice, 13(6), 1842–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfada, A. (2019). Does fiscal decentralization encourage corruption in local governments? Evidence from Indonesia. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 12(3), 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananta, A., Utami, D. R. W. W., & Handayani, N. B. (2016). Statistics on ethnic diversity in the land of Papua, Indonesia. Asia & the Pacific Policy Studies, 3(3), 458–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antlöv, H., Wetterberg, A., & Dharmawan, L. (2016). Village governance, community life, and the 2014 village law in Indonesia. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 52(2), 161–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arifin, B., Wicaksono, E., Tenrini, R. H., Wardhana, I. W., Setiawan, H., Damayanty, S. A., Solikin, A., Suhendra, M., Saputra, A. H., Ariutama, G. A., Djunedi, P., Rahman, A. B., & Handoko, R. (2020). Village fund, village-owned-enterprises, and employment: Evidence from Indonesia. Journal of Rural Studies, 79, 382–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badrudin, R., Dewanti, B. A., & Siregar, B. (2021). Are village funds effective in improving social welfare in east Indonesia? Studies of Applied Economics, 39(4), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beshi, T. D., & Kaur, R. (2020). Public trust in local government: Explaining the role of good governance practices. Public Organization Review, 20(2), 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyay, B. N. (2012). Seamless sustainable transport connectivity in Asia and the Pacific: Prospects and challenges. International Economics and Economic Policy, 9(2), 147–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodin, Ö., & Crona, B. I. (2009). The role of social networks in natural resource governance: What relational patterns make a difference? Global Environmental Change, 19(3), 366–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boufounou, P., Eriotis, N., Kounadeas, T., Argyropoulos, P., & Poulopoulos, J. (2024). Enhancing internal control mechanisms in local government organizations: A crucial step towards mitigating corruption and ensuring economic development. Economies, 12(4), 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bräutigam, D. (2004). The people’s budget? Politics, participation and pro-poor policy. Development Policy Review, 22(6), 653–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkerhoff, D. W., & Brinkerhoff, J. M. (2015). Public sector management reform in developing countries: Perspectives beyond NPM orthodoxy. Public Administration and Development, 35(4), 222–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunnschweiler, C. N., & Bulte, E. H. (2008). The resource curse revisited and revised: A tale of paradoxes and red herrings. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 55(3), 248–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Arce, K., & Vanclay, F. (2020). Transformative social innovation for sustainable rural development: An analytical framework to assist community-based initiatives. Journal of Rural Studies, 74, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D., & Ngacho, C. (2017). Critical success factors influencing the performance of development projects: An empirical study of Constituency Development Fund projects in Kenya. IIMB Management Review, 29(4), 276–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diansari, R. E., Musah, A. A., & Binti Othman, J. (2023). Factors affecting village fund management accountability in Indonesia: The moderating role of prosocial behaviour. Cogent Business & Management, 10(2), 2219424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DJPK KEMENKEU. (2024). Keputusan Menteri Keuangan Nomor 352 Tahun 2024 tentang Rincian Insentif Desa Setiap Desa Tahun Anggaran 2024. Kementerian Keuangan Direktorat Jenderal Perimbangan Keuangan. Available online: https://djpk.kemenkeu.go.id/?p=55483 (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Donaldson, L. (2001). The contingency theory of organizations. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Dushkova, D., & Ivlieva, O. (2024). Empowering communities to act for a change: A review of the community empowerment programs towards sustainability and resilience. Sustainability, 16(19), 8700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Anshasy, A. A., & Katsaiti, M.-S. (2013). Natural resources and fiscal performance: Does good governance matter? Journal of Macroeconomics, 37, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernawati, E., Tajuddin, T., & Nur, S. (2021). Does government expenditure affect regional inclusive growth? An experience of implementing village fund policy in Indonesia. Economies, 9(4), 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M. (2012). Beyond the integrity paradox—towards ‘good enough’ governance? Policy Studies, 33(1), 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauzi, F. Z., Murti, A. A. G. B., Imamah, L. A., & Hapsari, N. (2019). Infrastructure development in Papua: Features and challenges. Policy & Governance Review, 3(3), 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiling, J., Burkle, F. M., Amundson, D., Dominguez-Cherit, G., Gomersall, C. D., Lim, M. L., Luyckx, V., Sarani, B., Uyeki, T. M., West, T. E., Christian, M. D., Devereaux, A. V., Dichter, J. R., & Kissoon, N. (2014). Resource-poor settings: Infrastructure and capacity building. Chest, 146(4), e156S–e167S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginting, A. H., Widianingsih, I., Mulyawan, R., & Nurasa, H. (2024). Village fund program in Cibeureum and Sukapura village, Bandung Regency, Indonesia: Problems, risks, and solutions. Cogent Social Sciences, 10(1), 2303452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handayani, E., Garad, A., Suyadi, A., & Tubastuvi, N. (2023). Increasing the performance of village services with good governance and participation. World Development Sustainability, 3, 100089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, C., Nyaranga, M. S., & Hongo, D. O. (2022). Enhancing public participation in governance for sustainable development: Evidence from Bungoma County, Kenya. SAGE Open, 12(1), 21582440221088856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartojo, N., Ikhsan, M., Dartanto, T., & Sumarto, S. (2022). A growing light in the lagging region in Indonesia: The impact of village fund on rural economic growth. Economies, 10(9), 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilmawan, R., Aprianti, Y., Vo, D. T. H., Yudaruddin, R., Bintoro, R. F. A., Fitrianto, Y., & Wahyuningsih, N. (2023). Rural development from village funds, village-owned enterprises, and village original income. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 9(4), 100159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M., Mendiratta, V., & Savastano, S. (2024). Agricultural and rural development interventions and poverty reduction: Global evidence from 16 impact assessment studies. Global Food Security, 43, 100806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indraningsih, K. S., Nahraeni, W., Agustian, A., & Gunawan, E. (2021). The impact of the use of village funds on sustainable agricultural development. E3S Web of Conferences, 232, 1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indrawan, M., Sumule, A., Wijaya, A., Kapisa, N., Wanggai, F., Ahmad, M., Mambai, B. V., & Heatubun, C. D. (2019). A time for locally driven development in Papua and West Papua. Development in Practice, 29(6), 817–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. F. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs, and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3, 305–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jubery, M., Moeljadi, M., Fajri, A. C., & Atim, D. (2017). The perspective of the Agency Theory in budget preparation of local government and its implementation on budget performance and financial decentralization to realize performance of local government of regencies and cities in Banten Province. Russian Journal of Agricultural and Socio-Economic Sciences, 62(2), 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, N., & Barstow, C. K. (2022). Rural transportation infrastructure in low- and middle-income countries: A review of impacts, implications, and interventions. Sustainability, 14(4), 2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kania, I., Anggadwita, G., & Alamanda, D. T. (2021). A new approach to stimulate rural entrepreneurship through village-owned enterprises in Indonesia. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy, 15(3), 432–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KEMENDESA. (2025). Pemeringkatan BUMDesa/BUMDesa Bersama. Kementerian Desa, Pembangunan Daerah Tertinggal, Dan Transmigrasi. Available online: https://pemeringkatan.kemendesa.go.id/ (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Kewo, C. L., & Kewo, S. T. (2024). Measurement of factors influencing village financial statements quality. Journal of Economics, Business, and Accountancy Ventura, 27(1), 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiryluk-Dryjska, E., & Beba, P. (2018). Region-specific budgeting of rural development funds—An application study. Land Use Policy, 77, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacroix, T., Levitt, P., & Vari-Lavoisier, I. (2016). Social remittances and the changing transnational political landscape. Comparative Migration Studies, 4(1), 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, P. R., & Lorsch, J. W. (1967). Differentiation and integration in complex organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 12(1), 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledezma, J. F. M. (2023). Rediscovering rural territories: Local perceptions and the benefits of collective mapping for sustainable development in Colombian communities. Research in Globalization, 7, 100153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitt, P., & Lamba-Nieves, D. (2011). Social remittances revisited. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 37(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Liu, H., & Chang, W.-Y. (2024). Evaluating the effect of fiscal support for agriculture on three-industry integration in Rural China. Agriculture, 14(6), 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H., & Peng, P. (2025). Impacts of digital inclusive finance, human capital and digital economy on rural development in developing countries. Finance Research Letters, 73, 106654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, D., Remete, A.-N., Corda, A.-M., Nastasoiu, I.-A., Lazăr, P.-S., Pop, I.-A., & Luca, T.-I. (2022). Territorial distribution of EU funds allocation for developments of Rural Romania during 2014–2020. Sustainability, 14(1), 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manurung, E. T., Maratno, S. F. E., Permatasari, P., Rahman, A. B., Qisthi, R., & Manurung, E. M. (2022). Do village allocation funds contribute towards alleviating hunger among the local community (SDG#2)? An insight from Indonesia. Economies, 10(7), 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Vazquez, J., Lago-Peñas, S., & Sacchi, A. (2017). The impact of fiscal decentralization: A survey. Journal of Economic Surveys, 31(4), 1095–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, P. F., de Castro-Pardo, M., Barroso, V. M., & Azevedo, J. C. (2020). Assessing sustainable rural development based on ecosystem services vulnerability. Land, 9(7), 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oktarini, L., & Kawano, H. (2019). Telecommunication access business model options in Maluku and Papua, the less-favored business regions in Indonesia. Digital Policy, Regulation and Governance, 21(4), 384–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S., & Wahhaj, Z. (2017). Fiscal decentralisation, local institutions and public good provision: Evidence from Indonesia. Journal of Comparative Economics, 45(2), 383–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Permatasari, P., Ilman, A. S., Tilt, C. A., Lestari, D., Islam, S., Tenrini, R. H., Rahman, A. B., Samosir, A. P., & Wardhana, I. W. (2021). The village fund program in Indonesia: Measuring the effectiveness and alignment to sustainable development goals. Sustainability, 13(21), 12294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phoek, I., Bhaumik, A., Isaac, O., & Tjilen, A. (2024). How village funds influence economic development in South Papua, Indonesia. Problems and Perspectives in Management, 22(1), 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, I. R., Wibowo, R. A., Purwadi, Andari, T., Asrori, Christy, N. N., Santoso, C. W., Harefa, H. Y., & Suryawardana, E. (2025). Village-owned enterprises perspectives towards challenges and opportunities in rural entrepreneurship: A qualitative study with Maxqda tools. Administrative Sciences, 15(3), 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rante, Y., & Warokka, A. (2013). The interrelated nexus of indigenous economic growth and small business development: Do local culture, government role, and entrepreneurial behavior play the role? Journal of Innovation Management in Small & Medium Enterprises, 2013, 360774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rijke, J., Brown, R., Zevenbergen, C., Ashley, R., Farrelly, M., Morison, P., & van Herk, S. (2012). Fit-for-purpose governance: A framework to make adaptive governance operational. Environmental Science & Policy, 22, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Navas, P. M., Morales, N. M., & Lalinde, J. M. (2021). Transparency for participation through the communication approach. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 10(9), 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roldan, C. S., Méndez Giraldo, G. A., & López Santana, E. (2023). Sustainable development in rural territories within the last decade: A review of the state of the art. Heliyon, 9(7), e17555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rout, S. K., Chandrashekar, S., & Kadam, S. M. (2022). Resource flow and fund management at district level in Odisha: Evidence for improving district health systems in developing countries. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management, 37(4), 2135–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabet, N. S., & Khaksar, S. (2024). The performance of local government, social capital and participation of villagers in sustainable rural development. The Social Science Journal, 61(1), 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siburian, M. E. (2022). The link between fiscal decentralization and poverty—Evidence from Indonesia. Journal of Asian Economics, 81, 101493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidik, F., & Habibi, M. (2024). A prize for the village ruling class: “Village funds” and class dynamics in Rural Indonesia. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 54(3), 387–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simangunsong, F., & Wicaksono, S. (2017). Evaluation of village fund management in Yapen Islands Regency Papua Province (case study at PasirPutih Village, South Yapen District). Journal of Social Science, 5(9), 250–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sisoumang, B., Wangwacharakul, V., & Limsombunchai, V. (2011, October 13–15). The operation and management of village development fund in Champasak Province, Lao PDR. ASAE 7th International Conference, Hanoi, Vietnam. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smas, M. H., Mokay, M. M., Nurhayati, E., & Margana. (2025). Overcoming extreme poverty through the utilisation of village funds: A case study in Indonesia. Societal Impacts, 6, 100128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smoke, P. (2015). Managing public sector decentralization in developing countries: Moving beyond conventional recipes. Public Administration and Development, 35(4), 250–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohail, S., Ullah, S., & Javid, A. Y. (2022). Fiscal decentralization, institutional quality, and government size: An asymmetry analysis for Asian economies. Transnational Corporations Review, 14(3), 256–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suffah, F., Gamayuni, R. R., & Dewi, F. G. (2020). A study of village fund management to achieve good governance. In S. Bangsawan, M. S. Mahrinasari, E. Hendrawat, R. Gamayuni, Nairobi, H. D. Mulyaningsih, A. W. Rachmawati, & S. Rahmawati (Eds.), The future opportunities and challenges of business in digital era 4.0 (pp. 249–252). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukosol, C., Teppitaki, P., & Yodkamol, C. (2020). Evaluation of the operational efficiency of village development fund in Champasak Province, Lao PDR. International Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 10(2), 001–007. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker, C. M., Alcantara-Ayala, I., Gunya, A., Jimenez, E., Klein, J. A., Xu, J., & Bigler, S. L. (2021). Challenges for governing mountains sustainably: Insights from a global survey. Mountain Research and Development, 41(2), R10–R20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udjianto, D., Hakim, A., Domai, T., Suryadi, S., & Hayat, H. (2021). Community development and economic welfare through the village fund policy. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 8(1), 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Doeveren, V. (2011). Rethinking good governance. Public Integrity, 13(4), 301–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahyudi, S., Achmad, T., & Pamungkas, I. D. (2022). Prevention village fund fraud in Indonesia: Moral sensitivity as a moderating variable. Economies, 10(1), 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L., Wu, Z., Wang, T., Ding, K., & Chen, Y. (2022). Villagers’ satisfaction evaluation system of rural human settlement construction: Empirical study of Suzhou in China’s rapid urbanization area. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(18), 11472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y., Appiah, D., Zulu, B., & Adu-Poku, K. A. (2024). Integrating rural development, education, and management: Challenges and strategies. Sustainability, 16(15), 6474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Category | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Province | Papua | 100 | 47.17% |

| South Papua | 70 | 33.02% | |

| Central Papua | 24 | 11.32% | |

| Mountain Papua | 18 | 8.49% | |

| Gender | Male | 200 | 94.34% |

| Female | 12 | 5.66% | |

| Age | 30–39 | 66 | 31.13% |

| 40–49 | 49 | 23.11% | |

| 50–59 | 64 | 30.19% | |

| 60–64 | 33 | 15.57% | |

| Education | Primary/Middle School | 23 | 10.85% |

| High School | 77 | 36.32% | |

| Bachelor’s | 76 | 35.85% | |

| Diploma | 36 | 16.98% | |

| Tenure | 1–5 years | 86 | 40.57% |

| 6–10 years | 68 | 32.08% | |

| >10 years | 58 | 27.36% |

| Test | Result |

|---|---|

| KMO Measure | 0.935 |

| Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity | χ2(561) = 4830.256, p < 0.001 |

| Total Variance Explained | 68.988% (7 factors) |

| Eigenvalues > 1 | 7 |

| Extraction Method | Principal Component Analysis |

| Rotation Method | Varimax |

| Factor | Indicator | Loading | Eigenvalue | % of Variance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1: Village Fund Planning Quality | X25. Government agencies provide coaching and mentoring in planning the village fund. | 0.808 | 5.665 | 16.663 |

| X4. The plan is based on the village’s priority needs. | 0.780 | |||

| X2. The plan aligns with village needs, priorities, and potentials. | 0.762 | |||

| X5. The plan considers local village resources and potentials. | 0.760 | |||

| X1. The village fund spending plan is developed effectively. | 0.724 | |||

| X3. The plan aims to foster development of the local economic area. | 0.715 | |||

| X14. The village government possesses the capability to formulate the fund plan. | 0.702 | |||

| X15. The village fund budget is formulated clearly and purposefully. | 0.574 | |||

| Factor 2: Fund Implementation and Utilization | X18. It is used for empowering villagers. | 0.787 | 4.022 | 11.830% |

| X33. The fund is disbursed efficiently and in a timely manner. | 0.732 | |||

| X17. The fund employs local labor. | 0.729 | |||

| X16. The fund is used to utilize local natural resources. | 0.644 | |||

| X20. Fund usage follows principles of accountability and transparency. | 0.616 | |||

| X19. It is utilized according to the villagers’ expectations. | 0.534 | |||

| Factor 3: Financial Management Capacity | X9. Officials managing the fund have competence in finance and accounting. | 0.756 | 3.460 | 10.176% |

| X26. Regular training is provided to fund managers on financial management. | 0.744 | |||

| X27. Fund transactions are recorded and reported digitally. | 0.680 | |||

| X11. A technology-based financial management system (e.g., SISKEUDES) is used. | 0.633 | |||

| X34. Village officials are skilled in using IT for managing funds. | 0.620 | |||

| Factor 4: Social and Economic Impact | X21. The fund increases agricultural production and income. | 0.844 | 2.951 | 8.679% |

| X24. It improves the village’s infrastructure quality. | 0.811 | |||

| X22. It enhances villagers’ welfare. | 0.802 | |||

| X23. It contributes to more equitable income distribution among villagers. | 0.744 | |||

| Factor 5: Ethical Governance and Oversight | X29. External or independent oversight monitors fund usage. | 0.710 | 2.758 | 8.111% |

| X13. Village leaders exhibit high integrity in public fund management. | 0.676 | |||

| X28. Financial decisions are made transparently and accountably. | 0.646 | |||

| X12. There is an internal audit mechanism verifying fund use. | 0.639 | |||

| Factor 6: Community Participation in Planning | X8. Community proposals and aspirations are used as input in planning. | 0.827 | 2.463 | 7.245% |

| X7. Villagers are actively involved in fund planning. | 0.758 | |||

| X6. The fund plan is formulated through consensus with villagers. | 0.717 | |||

| X10. The number of staff handling village funds is sufficient. | 0.459 | |||

| Factor 7: Mandatory Fund Disclosure and Reporting | X31. Fund realization is communicated to villagers through village deliberations. | 0.702 | 2.137 | 6.284% |

| X32. The realization is publicized via local information media (e.g., village noticeboard). | 0.701 | |||

| X30. Fund realization is reported in a timely manner. | 0.698 |

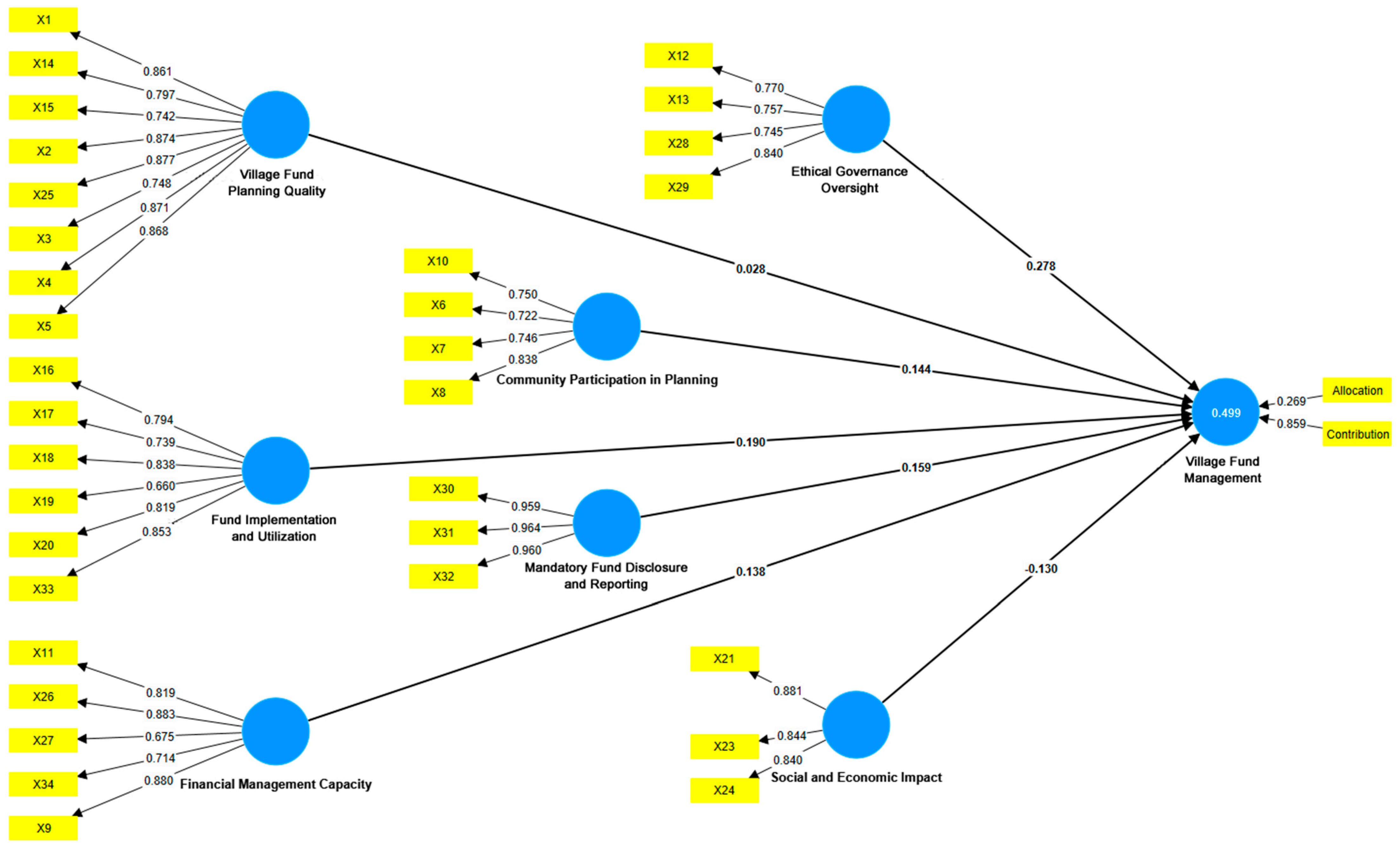

| Construct | Item | Outer Loadings | CA | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1: Village Fund Planning Quality | X1 | 0.861 | 0.936 | 0.947 | 0.692 |

| X2 | 0.874 | ||||

| X3 | 0.748 | ||||

| X4 | 0.871 | ||||

| X5 | 0.868 | ||||

| X14 | 0.797 | ||||

| X15 | 0.742 | ||||

| X25 | 0.877 | ||||

| Factor 2: Fund Implementation and Utilization | X16 | 0.794 | 0.875 | 0.906 | 0.619 |

| X17 | 0.739 | ||||

| X18 | 0.838 | ||||

| X19 | 0.660 | ||||

| X20 | 0.819 | ||||

| X33 | 0.853 | ||||

| Factor 3: Financial Management Capacity | X9 | 0.880 | 0.855 | 0.897 | 0.638 |

| X11 | 0.819 | ||||

| X26 | 0.883 | ||||

| X27 | 0.675 | ||||

| X34 | 0.714 | ||||

| Factor 4: Social and Economic Impact | X21 | 0.881 | 0.817 | 0.891 | 0.732 |

| X22 | Not valid | ||||

| X23 | 0.844 | ||||

| X24 | 0.840 | ||||

| Factor 5: Ethical Governance and Oversight | X12 | 0.770 | 0.783 | 0.860 | 0.607 |

| X13 | 0.757 | ||||

| X28 | 0.745 | ||||

| X29 | 0.840 | ||||

| Factor 6: Community Participation in Planning | X6 | 0.722 | 0.765 | 0.849 | 0.586 |

| X7 | 0.746 | ||||

| X8 | 0.838 | ||||

| X10 | 0.750 | ||||

| Factor 7: Mandatory Fund Disclosure and Reporting | X30 | 0.959 | 0.959 | 0.973 | 0.924 |

| X31 | 0.964 | ||||

| X32 | 0.960 |

| Construct | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Village Fund Planning Quality | 2.497 | ||||||

| 2. Fund Implementation and Utilization | 0.741 | 2.367 | |||||

| 3. Financial Management Capacity | 0.648 | 0.615 | 2.086 | ||||

| 4. Social and Economic Impact | 0.387 | 0.316 | 0.441 | 1.203 | |||

| 5. Ethical Governance and Oversight | 0.662 | 0.715 | 0.672 | 0.405 | 1.883 | ||

| 6. Community Participation in Planning | 0.503 | 0.503 | 0.667 | 0.304 | 0.561 | 1.527 | |

| 7. Mandatory Fund Disclosure and Reporting | 0.733 | 0.744 | 0.622 | 0.305 | 0.644 | 0.459 | 2.437 |

| Construct | Indicator | Outer Weight | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Village Fund Management | Contribution | 0.859 | 1.203 |

| Allocation | 0.269 | 1.203 |

| Metric | Construct | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient of Determination | Village Fund Management | R2 = 0.499 R2 Adjusted = 0.482 | This value indicates that the seven factors collectively explain 49.9% of the variance in village fund management, which is considered a moderate predictive power. |

| Community Participation in Planning | f2 = 0.027 | Small effect size | |

| Ethical Governance and Oversight | f2 = 0.082 | Small to medium effect size | |

| Financial Management Capacity | f2 = 0.018 | Small effect size | |

| Effect Size | Fund Implementation and Utilization | f2 = 0.030 | Small effect size |

| Social and Economic Impact | f2 = 0.028 | Small effect size | |

| Mandatory Fund Disclosure and Reporting | f2 = 0.021 | Small effect size | |

| Village Fund Planning Quality | f2 = 0.001 | No effect | |

| Predictive Relevance | Village Fund Management | Q2 = 0.303 | The value of Q2 > 0 indicates that the model has predictive relevance. |

| Relationship | Path Coefficient | t-Value | p-Value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community Participation in Planning → Village Fund Management | 0.144 | 2.461 | 0.014 ** | Supported |

| Ethical Governance and Oversight → Village Fund Management | 0.278 | 3.898 | 0.000 *** | Supported |

| Financial Management Capacity → Village Fund Management | 0.138 | 1.968 | 0.049 ** | Supported |

| Fund Implementation and Utilization → Village Fund Management | 0.190 | 3.576 | 0.000 *** | Supported |

| Social and Economic Impact → Village Fund Management | −0.130 | 2.558 | 0.011 ** | Supported |

| Mandatory Fund Disclosure and Reporting → Village Fund Management | 0.159 | 2.967 | 0.003 *** | Supported |

| Village Fund Planning Quality → Village Fund Management | 0.028 | 393 | 0.695 | Not Supported |

| Relationship | Region | Natural Resources | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coastal | Mountainous | Diff. | Rich | Minimal | Diff. | |

| CPP → VFM | 0.145 ** | −0.049 | 0.194 * | 0.155 ** | 0.175 | −0.020 |

| EGO → VFM | 0.185 ** | 0.060 | 0.125 | 0.256 ** | 0.405 ** | −0.150 |

| FMC → VFM | 0.191 ** | 0.224 | −0.033 | 0.186 *** | 0.419 | 0.605 ** |

| FIU → VFM | 0.257 *** | 0.051 | 0.206 | 0.250 *** | 0.013 | 0.263 * |

| SEI → VFM | −0.151 ** | −0.140 | −0.011 | −0.104 * | 0.259 | 0.155 |

| MFD → VFM | 0.094 | −0.105 | 0.199 * | 0.105 | 0.338 * | −0.233 |

| FPQ → VFM | 0.846 *** | 0.189 *** | 0.657 *** | −0.001 | 0.383 | −0.384 * |

| Relationship | Transport Access | Population Makeup | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Easy | Difficult | Diff. | Many Migrants | The Majority of Papuan People | Diff. | |

| CPP → VFM | 0.190 ** | 0.085 | 0.105 | 0.170 *** | −0.045 | 0.214 * |

| EGO → VFM | 0.206 ** | −0.034 | 0.241 | 0.240 *** | 0.054 | 0.186 |

| FMC → VFM | 0.183 ** | 0.200 | −0.017 | 0.142 * | 0.245 ** | −0.103 |

| FIU → VFM | 0.249 *** | 0.166 * | 0.083 | 0.231 *** | 0.221 ** | 0.010 |

| SEI → VFM | −0.130 ** | −0.024 | −0.106 | −0.135 | −0.017 | −0.119 |

| MFD → VFM | 0.045 | −0.173 * | 0.219 ** | 0.061 | −0.149 | 0.210 |

| FPQ → VFM | 0.831 *** | 0.218 *** | 0.613 *** | 0.197 *** | 0.721 ** | −0.524 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Warokka, A.; Warokka, V.; Aqmar, A.Z. Financing Rural Futures: Governance and Contextual Challenges of Village Fund Management in Underdeveloped Regions. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 603. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18110603

Warokka A, Warokka V, Aqmar AZ. Financing Rural Futures: Governance and Contextual Challenges of Village Fund Management in Underdeveloped Regions. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(11):603. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18110603

Chicago/Turabian StyleWarokka, Ari, Vetaroy Warokka, and Aina Zatil Aqmar. 2025. "Financing Rural Futures: Governance and Contextual Challenges of Village Fund Management in Underdeveloped Regions" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 11: 603. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18110603

APA StyleWarokka, A., Warokka, V., & Aqmar, A. Z. (2025). Financing Rural Futures: Governance and Contextual Challenges of Village Fund Management in Underdeveloped Regions. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(11), 603. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18110603