Non-Linear Impact of Environmental, Social, and Governance Scores on Deal Premiums

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. IIa: Theories Regarding the Impact of ESG on Firm Value and the Deal Premium

2.2. Empirical Studies Relating ESG Scores to Deal Premiums

3. Data and Data Summary

3.1. IIIa. Data Description

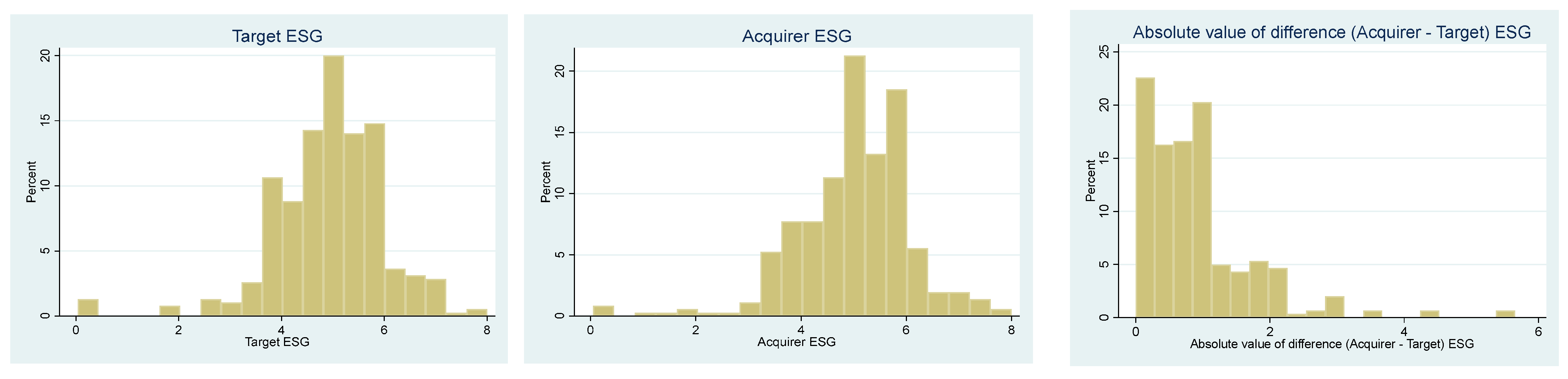

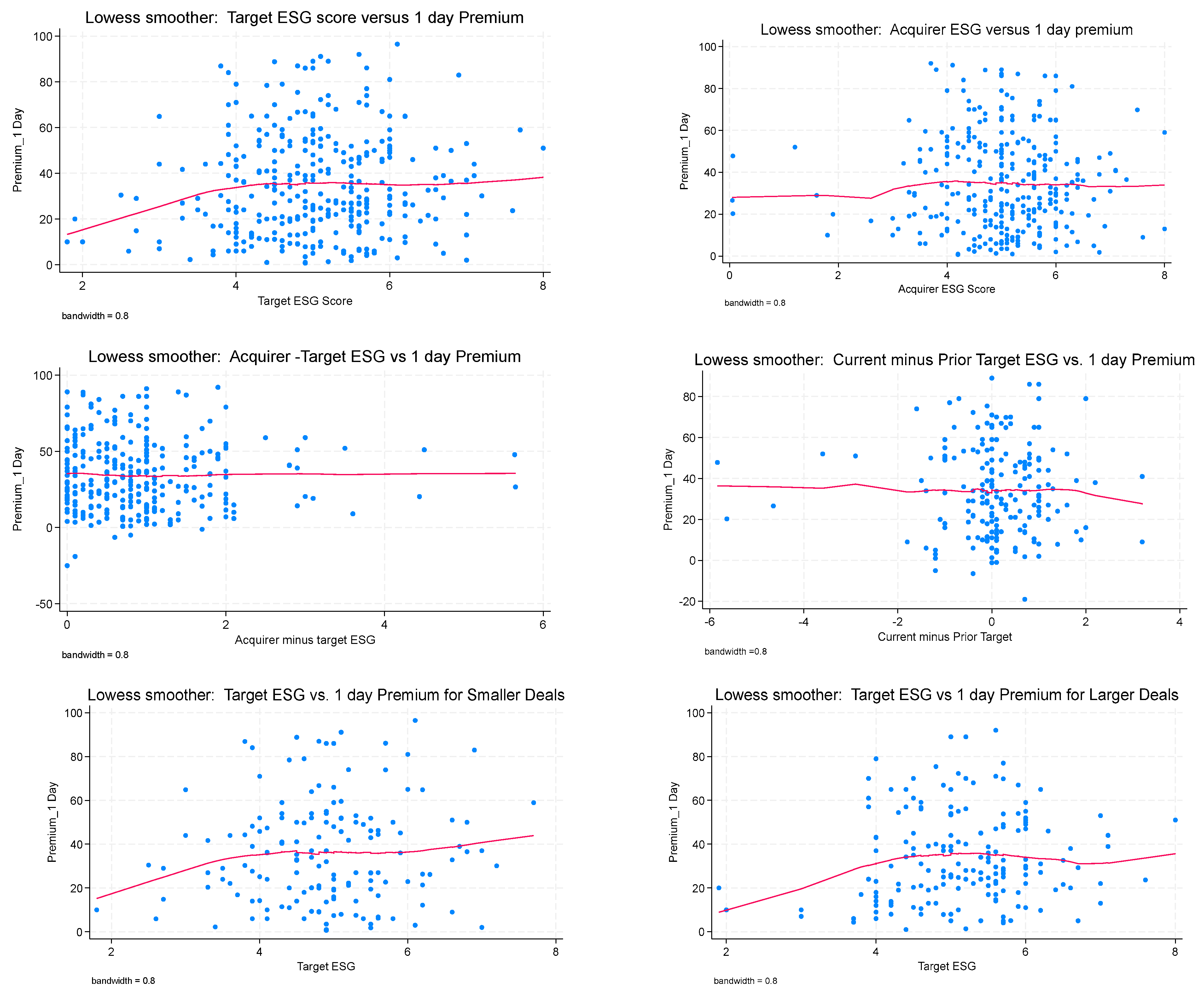

Explanatory Data Analysis

4. Hypotheses

- ○

- At low ESG levels, target firms will be viewed as riskier due to potential issues relating to poor governance, environmental concerns, or social controversies. As a result, acquirers will offer a relatively low deal premium for companies with these low ESG scores. However, as the ESG scores increase, so too will the deal premiums.

- ○

- At moderate ESG levels, targets are seen as stable but still offer room for improvement, making them the most attractive and synergistic acquisition opportunities. In this range, both acquirers and targets are likely to agree on a higher premium.

- ○

- At high ESG levels, targets may already be highly valued and well-managed, limiting the acquirer’s ability to generate additional value post-acquisition. This condition reduces the acquirer’s willingness to offer a high premium.

- ○

- For social scores, we contend the target’s social scores will impact the deal premium because the acquirer can gain value from increased productivity that stems from higher satisfaction levels among the target’s workforce where social ratings are high. However, the positive influence of social scores will reverse, after reaching a maximum, as similarly to the overall ESG score, the firm with high social scores is likely already highly valued.

- ○

- For governance scores, we believe that target governance scores exhibit an inverted U-shaped relationship with the deal premium because at low governance scores, improvements suggest a more resilient company. However, at higher governance levels, companies may be more difficult to integrate and change into the governance systems of the acquirer. That is certain controls (see Borghesi et al., 2019; van Essen et al., 2013) (e.g., shareholder-centric policies, independent boards, separation of the CEO and Chairman of the Board, etc.) that raise governance scores may present post-merger integration problems and thus reduce the upside potential of the merger.

5. Methodology

6. Results

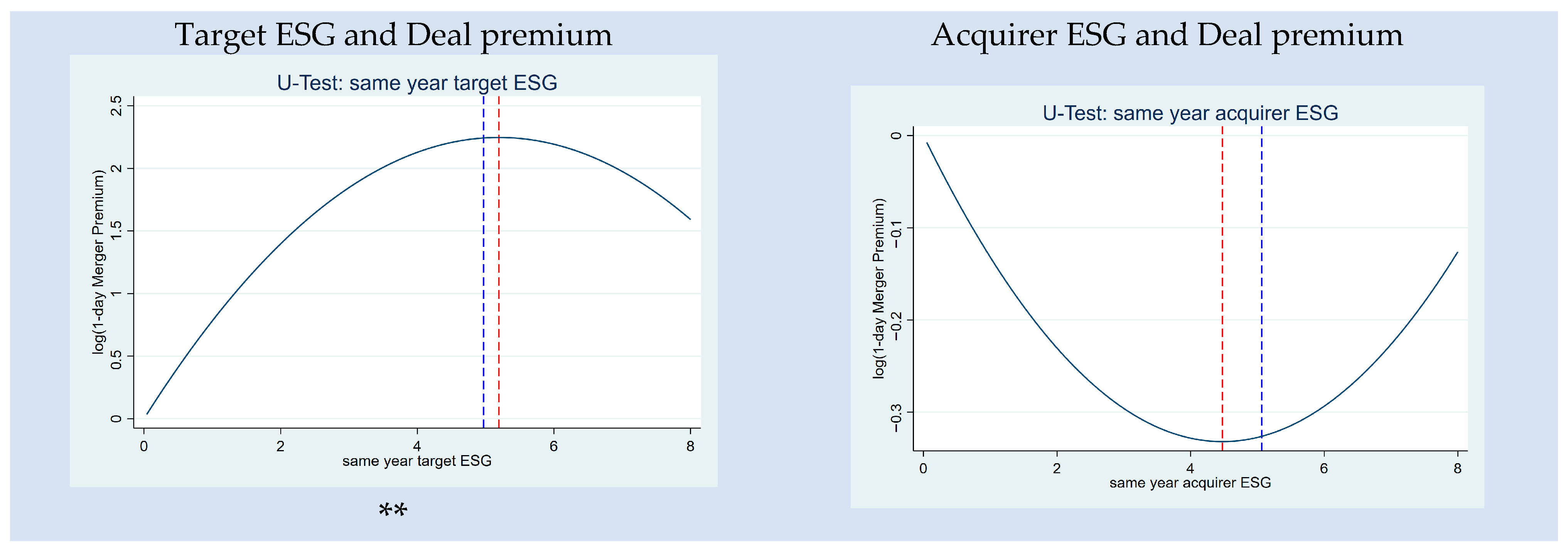

6.1. ESG and the Deal Premium

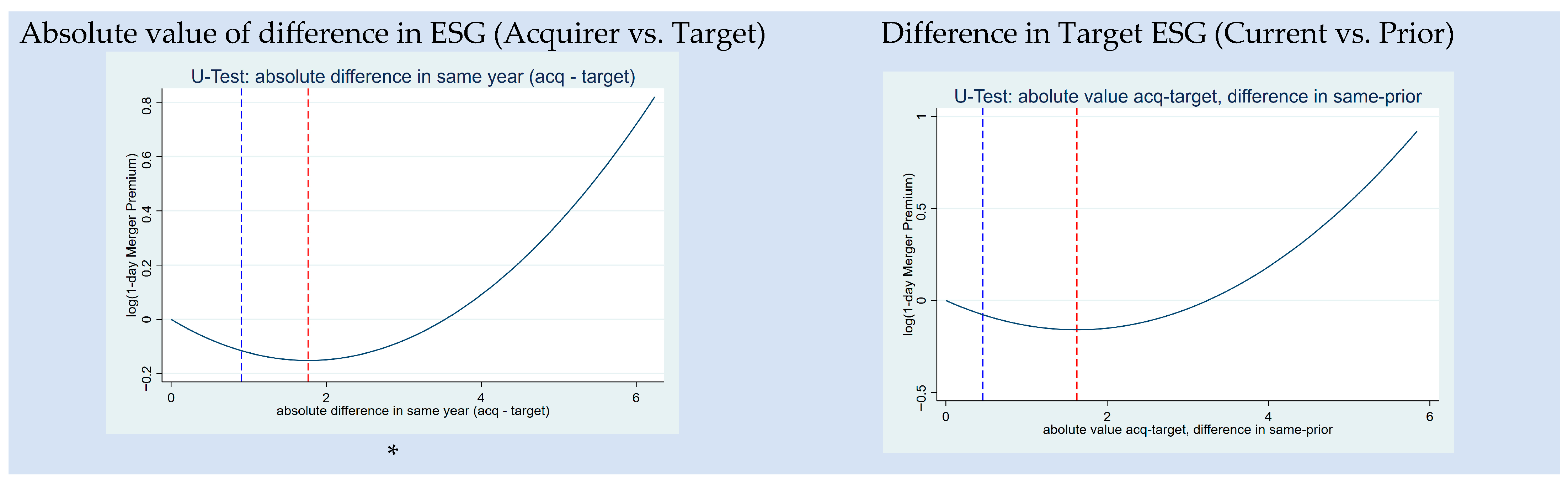

6.2. Differences in ESG (Acquirer vs. Target and Current vs. Prior Period) Scores and the Deal Premium

6.3. Analysis of Small Versus Large Deals

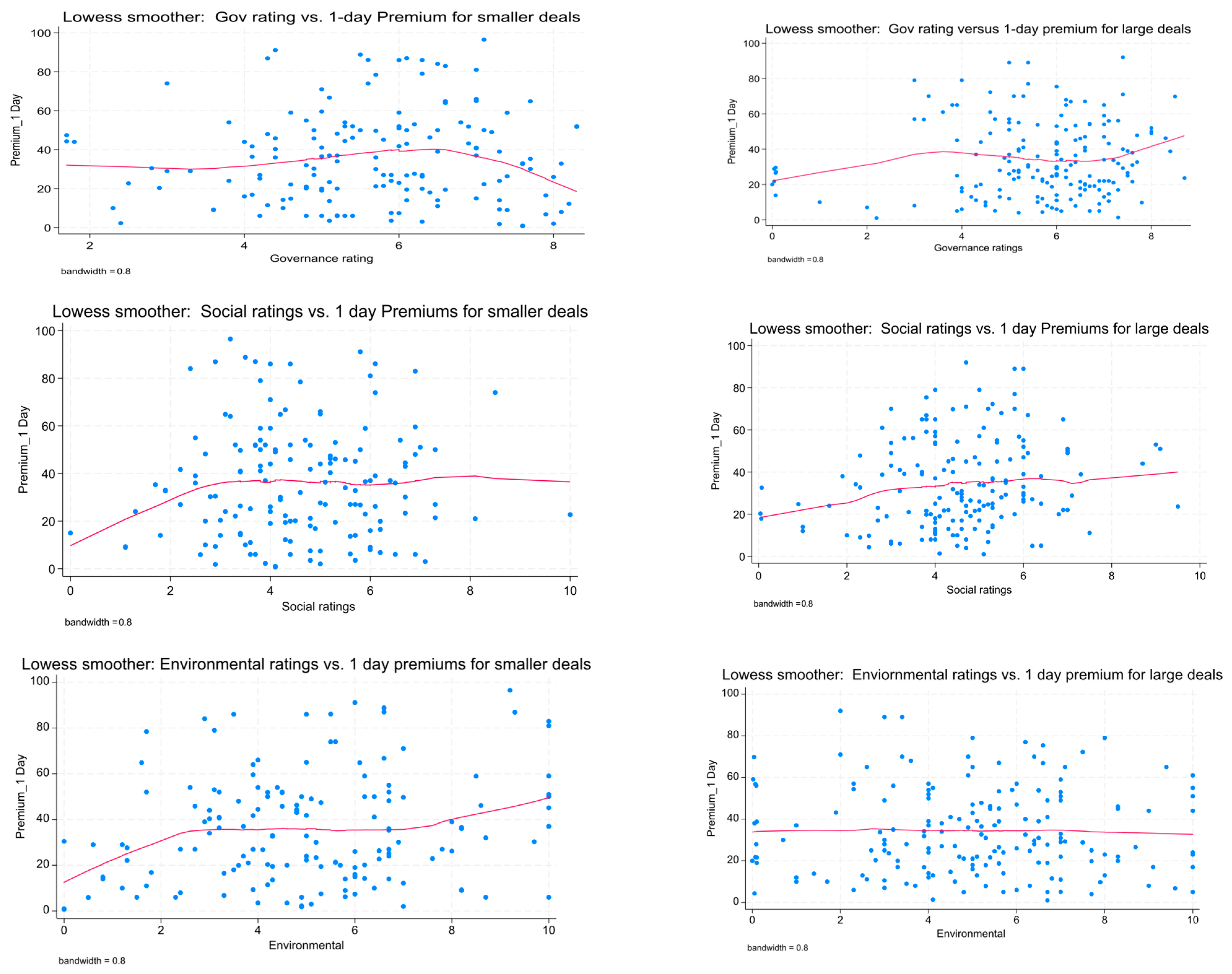

6.4. ESG Components, E, S, and G, and the Deal Premium

6.5. Robustness Check for Endogeneity

7. Discussion

7.1. Results Regarding Target ESG and Difference in ESG

7.2. Results Regarding Governance and Social Scores

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Dealvalue | %Cash | Acq ESG | Acq ESG sq. | Tgt ESG | Tgt ESG-sq | Diff ESG | Diff ESG-sq | Diff Yr Sq | Diff Yr ESG sq | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dealvalue | 1.0000 | |||||||||

| %cash | −0.1386 | 1.0000 | ||||||||

| Acq ESG | 0.0069 | 0.0491 | 1.0000 | |||||||

| Acq ESG-sq | 0.0002 | 0.0462 | 0.9628 | 1.0000 | ||||||

| Tgt ESG | 0.1233 | −0.0341 | 0.2611 | 0.2680 | 1.0000 | |||||

| Tgt ESG sq | 0.1664 | −0.0082 | 0.2721 | 0.2876 | 0.9610 | 1.0000 | ||||

| Diff ESG | 0.0845 | 0.0771 | −0.1451 | −0.0013 | −0.3258 | −0.2065 | 1.0000 | |||

| Diff ESG-sq | 0.1118 | 0.0444 | −0.2126 | −0.0610 | −0.3582 | −0.2180 | 0.9116 | 1.0000 | ||

| Diff Yr ESG | 0.1324 | 0.0236 | 0.0062 | 0.0095 | −0.4172 | 0.2303 | 0.4668 | 0.5307 | 1.0000 | |

| Diff Yr ESG -sq | 0.1106 | 0.0523 | 0.0320 | 0.0291 | −0.5112 | −0.3036 | 0.5231 | 0.6339 | 0.902 | 1.0000 |

| Acq diff | Acq diff-sq | Diff (diff) | Diff (diff) sq | SharesAQ | RelSale | Completed | Competitive | |||

| Acq diff | 1.0000 | |||||||||

| Acq diff-sq | 0.8860 | 1.0000 | ||||||||

| Diff (diff) | 0.6019 | 0.6280 | 1.0000 | |||||||

| Diff (diff) sq | 0.4717 | 0.5975 | 0.5975 | 1.0000 | ||||||

| SharesAQ | 0.0420 | 0.0465 | 0.0927 | 0.0689 | 1.0000 | |||||

| RelSale | −0.0217 | 0.0002 | −0.0070 | −0.0185 | 0.0503 | 1.0000 | ||||

| Completed | 0.0710 | 0.0566 | 0.0845 | 0.0633 | −0.0137 | 0.0438 | 1.0000 | |||

| Competitive | −0.0452 | 0.0277 | −0.0334 | −0.0057 | 0.0087 | −0.0539 | −0.4332 | 1.0000 | ||

| Dealvalue | %cash | AEnv | AEnv-sq | Env | Env-sq | ASoc | Asoc-sq | Soc | Soc sq | |

| Dealvalue | 1.0000 | |||||||||

| % cash | 0.1415 | 1.0000 | ||||||||

| AEnv | 0.1208 | 0.195 | 1.0000 | |||||||

| AEnv-sq | 0.2145 | 0.113 | 0.3834 | 1.0000 | ||||||

| Env | 0.2109 | 0.146 | 0.4078 | 0.9552 | 1.0000 | |||||

| Env-sq | 0.2145 | 0.113 | 0.3834 | 0.999 | 0.9552 | 1.0000 | ||||

| ASoc | −0.0050 | −0.034 | 0.1911 | 0.0571 | 0.0839 | 0.0571 | 1.0000 | |||

| Asoc-sq | −0.0091 | −0.041 | 0.1565 | 0.0420 | 0.0700 | 0.0420 | 0.9641 | 1.0000 | ||

| Soc | 0.1333 | 0.060 | 0.0815 | 0.1619 | 0.1477 | 0.1619 | 0.2558 | 0.2301 | 1.0000 | |

| Soc sq | 0.1175 | 0.053 | 0.0689 | 0.1754 | 0.1676 | 0.1754 | 0.2286 | 0.2125 | 0.9578 | 1.0000 |

| A gov | −0.0350 | −0.038 | 0.0384 | 0.0310 | 0.0658 | 0.0310 | 0.0642 | 0.0648 | 0.0164 | 0.0303 |

| Agov | Agov-sq | sharesAQ | RelSal | Completed | Competitive | |||||

| Agov-sq | 1.0000 | |||||||||

| sharesAQ | 0.0943 | 1.0000 | ||||||||

| RelSal | −0.0087 | 0.0457 | 1.0000 | |||||||

| Completed | −0.0408 | 0.0013 | 0.0416 | 1.0000 | ||||||

| Competitive | 0.1436 | 0.0993 | −0.0496 | −0.444 | 1.0000 |

| Response Variables 1-Week & 4-Week Deal Premium | Lpremium_ 1-Week (1) | Lpremium_ 1-Week (2) | Lpremium_ 1-Week (3) | Lpremium_ 1-Week (4) | Lpremium_ 4-Weeks (5) | Lpremium_ 4-Weeks (6) | Lpremium_ 4-Weeks (7) | Lpremium_ 4-Weeks (8) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Log deal value | 0.005 | −0.011 | 0.017 | 0.008 | 0.006 | −0.004 | 0.153 | −0.002 |

| (0.05) | (0.05) | (0.05) | (0.05) | (0.04) | (0.04) | (1.31) | (0.04) | |

| Percent cash | 0.004 *** | 0.004 *** | 0.004 *** | 0.004 *** | 0.005 *** | 0.005 *** | 0.121 *** | 0.005 *** |

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.03) | (0.00) | |

| Shares AQ | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | −0.039 | −0.001 |

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.07) | (0.00) | |

| Relative sales | 0.001 * | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 ** | 0.001 ** | 0.001 ** | 0.000 | 0.001 *** |

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |

| completed | 0.202 | 0.229 | 0.306 | 0.296 | 0.182 | 0.206 | 5.956 | 0.311 * |

| (0.18) | (0.19) | (0.21) | (0.22) | (0.15) | (0.16) | (4.94) | (0.18) | |

| competitive | 0.318 ** | 0.331 ** | 0.293 * | 0.332 ** | 0.123 | 0.148 | 8.124 * | 0.108 |

| (0.13) | (0.14) | (0.16) | (0.17) | (0.11) | (0.12) | (4.69) | (0.14) | |

| Target ESG | 0.788 *** | 0.874 *** | ||||||

| (0.28) | (0.26) | |||||||

| Target ESG-sq | −0.081 *** | −0.093 *** | ||||||

| (0.03) | (0.03) | |||||||

| Acquirer—Target | −0.183 * | −0.14 | ||||||

| ESG difference | (0.11) | (0.10) | ||||||

| Acquirer—Target | 0.0428 * | 0.0409 ** | ||||||

| ESG difference-sq | (0.02) | (0.02) | ||||||

| Current-Prior Target ESG diff | 0.29 (0.23) | 0.72 (7.11) | ||||||

| Current-Prior Target ESG diff-sq | −0.181 ** (0.09) | −1.98 (2.08) | ||||||

| Acq.–Target ESG (Current—Prior) | −0.156 (0.19) | −0.348 ** (0.15) | ||||||

| Acq—Target ESG (Current—Prior) -sq | 0.040 (0.04) | 0.083 *** (0.04) | ||||||

| Year effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Slope—low end | 29.2 | −4.1 | −0.18 | −2.4 | 29.1 | −0.14 | −1.13 | −8.7 |

| Slope—high end | −19.4 | 6.3 | 0.35 | 5.2 | −20.9 | 0.36 | −17.84 | 14.2 |

| Sasabuchi test stat. | 4.05 *** | 1.07 | 1.70 ** | 0.45 | 4.01 *** | 1.45 * | - | 1.42 * |

| Threshold (−β1/(2β2))/within data range | 4.81/yes 4.3/5.3 | 2.53/yes -Inf./Inf. | 2.13/yes -Inf./Inf. | 1.83/yes -Inf./Inf. | 4.65/yes 4.1/5.2 | 1.71/yes −5.55/2.44 | −0.39/no -Inf, 2.3/1.3, Inf. | 2.21/yes -Inf./Inf. |

| Observations | 275 | 279 | 270 | 241 | 235 | 229 | 237 | 215 |

| R-squared | 0.108 | 0.095 | 0.097 | 0.129 | 0.102 | 0.107 | 0.127 | 0.167 |

| Small Deals | Large Deals | Small Deals | Large Deals | Small Deals | Large Deals | Small Deals | Large Deals | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response Variables 1-Week & 4-Week Deal Premiums | Premium_1-Week (1) | Premium_1-Week (2) | Premium_1-Week (3) | Premium_1-Week (4) | Premium_4-Weeks (5) | Premium_4-Weeks (6) | Premium_4-Weeks (7) | Premium_4-Weeks (8) |

| Log deal value | −3.463 | −3.054 | −3.595 | −3.758 | −3.548 | −4.483 | −3.540 | −5.805 * |

| (3.878) | (2.925) | (4.713) | (2.972) | (5.107) | (3.067) | (5.898) | (3.008) | |

| Percent cash | 0.0639 | 0.155 *** | 0.0781 | 0.130 *** | 0.108 * | 0.169 *** | 0.131 * | 0.149 *** |

| (0.0502) | (0.0421) | (0.0555) | (0.0467) | (0.0628) | (0.0449) | (0.0697) | (0.0490) | |

| Shares AQ | −0.082 | 0.001 | −0.091 | −0.044 | 0.101 | 0.001 | 0.122 | −0.054 |

| (0.115) | (0.073) | (0.127) | (0.089) | (0.132) | (0.081) | (0.150) | (0.095) | |

| Relative sales | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 ** | 0.001 | 0.001 *** | 0.001 | 0.001 *** |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.0001) | (0.001) | (0.0001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| completed | 0.981 | 5.102 | 5.517 | 6.898 | 3.034 | 8.942 | 6.467 | 12.43 * |

| (8.465) | (5.705) | (9.151) | (6.740) | (8.729) | (5.763) | (8.855) | (6.887) | |

| competitive | −0.001 | 14.23 *** | 1.720 | 17.73 *** | −7.802 | 14.21 *** | −9.600 | 17.01 *** |

| (6.891) | (5.198) | (8.765) | (6.180) | (5.179) | (5.083) | (6.685) | (6.063) | |

| ESG | 32.10 ** | 30.91 *** | 25.77 * | 34.42 *** | ||||

| (12.53) | (8.334) | (13.38) | (8.478) | |||||

| ESG-squared | −3.414 *** | −3.035 *** | −2.936 ** | −3.430 *** | ||||

| (1.276) | (0.864) | (1.381) | (0.852) | |||||

| Acquire—Target ESG (Current—Prior) | −18.81 (12.79) | 2.158 (6.867) | −31.51 ** (15.70) | −2.815 (6.747) | ||||

| Acquire—Target ESG (Current—Prior) -sq | 6.483 (6.079) | −0.263 (1.361) | 11.14 (8.091) | 0.736 (1.255) | ||||

| Slope—low end | 32.1 | 30.9 | −18.8 | 2.1 | −31.5 | −2.8 | 25.7 | 34.4 |

| Slope—high end | −22.5 | −17.4 | 56.9 | −0.9 | 98.5 | 5.7 | −21.2 | −20.0 |

| Sasabuchi test stat. | 2.6 *** | 2.9 *** | 0.9 | 0.1 | 1.22 | 0.4 | 1.9 ** | 3.5 *** |

| Threshold (−β1/(2β2))/within data range | 4.7/yes | 5.09/yes | 1.45/yes | 4.1/no | 1.41/yes | 1.91/yes | 4.39/yes | 5.07/yes |

| 95% Fieller interval for extreme point | 3.6/5.4 | 4.4/6.2 | -Inf/Inf | -Inf/Inf | -Inf, 0.7/−0.04, Inf. | -- /Inf | 1.6/5.3 | 4.4/5.8 |

| Year effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | −5.888 | −35.93 | 64.70 * | 49.82 * | 1.699 | −31.08 | 61.41 | 67.88 ** |

| (42.65) | (29.72) | (38.20) | (28.47) | (47.53) | (30.70) | (48.87) | (28.19) | |

| Observations | 128 | 151 | 106 | 123 | 115 | 151 | 96 | 123 |

| R-squared | 0.128 | 0.223 | 0.125 | 0.229 | 0.116 | 0.242 | 0.142 | 0.265 |

| Response Variable 1-Week Deal Premium | Small Deals Target Env (1) | Large Deals Target Env (2) | Small Deals Acq Social (3) | Large Deals Acq Social (4) | Small Deals Target Social (5) | Large Deals Target Social (6) | Small Deals Acq Gov (7) | Large Deals Acq Gov (8) | Small Deals Target Gov (9) | Large Deals Target Gov (10) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Log deal value | −4.351 | −2.609 | −5.475 | −2.895 | −4.095 | −3.314 | −5.235 | −2.926 | −5.072 | −2.828 |

| (4.002) | (2.911) | (3.889) | (2.780) | (3.983) | (2.752) | (3.833) | (2.696) | (4.176) | (2.78) | |

| Percent cash | 0.0346 | 0.148 *** | 0.0673 | 0.147 *** | 0.0547 | 0.155 *** | 0.0658 | 0.150 *** | 0.0397 | 0.145 *** |

| (0.0511) | (0.0424) | (0.0493) | (0.0415) | (0.0501) | (0.0425) | (0.049) | (0.041) | (0.049) | (0.041) | |

| Relative sales | 7.65 × 10−5 | 0.002 * | 0.001 | 0.002 * | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 ** |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |

| completed | 4.616 | 5.366 | 5.254 | 3.961 | 5.425 | 5.955 | −0.056 | 0.022 | −0.056 | 0.022 |

| (8.027) | (5.559) | (8.148) | (5.470) | (8.387) | (5.667) | (0.119) | (0.075) | (0.119) | (0.075) | |

| competitive | 0.814 | 15.0 *** | 1.486 | 15.44 *** | 2.767 | 16.06 *** | 3.482 | 4.816 | 3.482 | 4.816 |

| (6.854) | (5.069) | (7.65) | (5.093) | (6.845) | (5.029) | (8.012) | (5.732) | (8.012) | (5.732) | |

| Shares AQ | −0.067 | 0.026 | −0.042 | 0.011 | −0.082 | 0.013 | 1.914 | 14.77 *** | 1.914 | 14.77 *** |

| (0.113) | (0.077) | (0.110) | (0.074) | (0.116) | (0.070) | (6.88) | (0.07) | (0.09) | (0.07) | |

| Environmental | 6.246 ** | |||||||||

| (3.113) | ||||||||||

| Environmental | −0.497 | |||||||||

| (0.319) | ||||||||||

| Acq Social | 8.925 | 7.263 ** | ||||||||

| (7.843) | (3.546) | |||||||||

| Acq Social-sq | −0.830 | −0.687 ** | ||||||||

| (0.803) | (0.346) | |||||||||

| Target Social | −0.218 | 10.74 ** | ||||||||

| (4.835) | (4.709) | |||||||||

| Target Social-sq | −0.0249 | −1.095 ** | ||||||||

| (0.502) | (0.539) | |||||||||

| Acq Gover | 4.213 | 6.254 | ||||||||

| (5.379) | (4.257) | |||||||||

| Acq Gover-sq | −0.584 | −0.758 * | ||||||||

| (0.573) | (0.450) | |||||||||

| Targ Gover | 14.63 * | 0.523 | ||||||||

| (8.127) | (3.772) | |||||||||

| Targ Gover-sq | −1.315 * | −0.0156 | ||||||||

| (0.763) | (0.429) | |||||||||

| Year effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Slope—low end | 6.2 | −2.0 | 8.9 | 7.3 | −0.2 | 10.7 | 4.2 | 6.2 | 14.6 | 0.5 |

| Slope—high end | −3.7 | 1.5 | −7.6 | −6.5 | −0.7 | −11.1 | −6.1 | −7.1 | −8.2 | 0.3 |

| Sasabuchi test stat. | 1.04 | 0.59 | 0.90 | 1.71 ** | - | 1.96 ** | 0.78 | 1.87 ** | 1.52 * | - |

| Threshold (−β1/(2β2))/within data range | 6.29/no | 5.75/no | 5.37/yes | 5.28/yes | −4.37/no | 4.90/yes | 3.6/yes | 4.1/yes | 5.6/yes | 16.7/no |

| 95% Fieller interval for extreme point | -Inf, 4.3/-0.37, Inf | -Inf/Inf | -Inf/Inf. | 1.9/94.4 | -Inf/Inf. | 3.9/10.2 | -Inf/Inf. | 1.3/36 | -Inf/Inf. | -Inf/Inf. |

| Year effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | 54.04 | 38.68 | 50.67 | 23.02 | 69.18 * | 18.67 | 66.45 * | 32.15 | 36.41 | 35.05 |

| (33.62) | (26.25) | (37.35) | (25.93) | (35.24) | (27.14) | (34.59) | (27.03) | (32.43) | (25.14) | |

| Observations | 128 | 151 | 125 | 150 | 128 | 151 | 125 | 150 | 128 | 151 |

| R-squared | 0.123 | 0.197 | 0.119 | 0.207 | 0.093 | 0.224 | 0.121 | 0.211 | 0.108 | 0.193 |

| Response Variable 4-Week Deal Premium | Small Deals Target Env (1) | Large Deals Target Env (2) | Small Deals Acq Social (3) | Large Deals Acq Social (4) | Small Deals Target Social (5) | Large Deals Target Social (6) | Small Deals Acq Gov (7) | Large Deals Acq Gov (8) | Small Deals Target Gov (9) | Large Deals Target Gov (10) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Log deal value | −4.259 | −3.723 | −4.516 | −4.623 | −4.075 | −4.963 * | −4.573 | −4.418 | −4.886 | −4.488 |

| (5.096) | (3.095) | (4.870) | (2.924) | (5.138) | (2.931) | (4.685) | (2.895) | (5.392) | (2.898) | |

| Percent cash | 0.0877 | 0.165 *** | 0.118 ** | 0.157 *** | 0.0855 | 0.167 *** | 0.108 * | 0.161 *** | 0.0908 | 0.157 *** |

| (0.0646) | (0.0448) | (0.0581) | (0.0443) | (0.0643) | (0.0453) | (0.061) | (0.044) | (0.061) | (0.044) | |

| Relative sales | 0.000 | 0.001 ** | 0.000 | 0.001 ** | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 ** |

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |

| completed | 5.848 | 8.983 * | 4.153 | 7.573 | 6.499 | 9.727 | 5.723 | 8.667 | 4.800 | 8.712 |

| (8.162) | (5.414) | (7.836) | (5.531) | (8.410) | (6.035) | (8.376) | (6.125) | (8.349) | (5.759) | |

| competitive | −7.228 | 14.82 *** | −8.640 | 15.30 *** | −5.854 | 16.06 *** | −8.053 | 15.49 *** | −7.134 | 15.02 *** |

| (5.14) | (4.95) | (5.722) | (5.142) | (5.33) | (5.355) | (6.24) | (5.486) | (5.410) | (5.275) | |

| Shares AQ | 0.108 | 0.026 | 0.124 | 0.014 | 0.107 | 0.013 | 0.132 | 0.0107 | 0.108 | 0.021 |

| (0.131) | (0.0827) | (0.123) | (0.0839) | (0.132) | (0.0745) | (0.126) | (0.077) | (0.140) | (0.081) | |

| Environmental | 3.382 | |||||||||

| (4.142) | ||||||||||

| Environmental | −0.322 | |||||||||

| (0.404) | ||||||||||

| Acq Social | 13.88 * | 8.247 *** | ||||||||

| (8.293) | (3.136) | |||||||||

| Acq Social-sq | −1.122 | −0.813 *** | ||||||||

| (0.818) | (0.296) | |||||||||

| Target Social | 3.529 | 11.31 ** | ||||||||

| (6.472) | (5.015) | |||||||||

| Target Social -sq | −0.428 | −1.149 ** | ||||||||

| (0.669) | (0.574) | |||||||||

| Acq Gover | 5.714 | |||||||||

| (4.133) | ||||||||||

| Acq Gover-sq | −0.745 * | |||||||||

| (0.437) | ||||||||||

| Targ Gover | 5.965 | 1.919 | ||||||||

| (12.74) | (3.616) | |||||||||

| Targ Gover-sq | −0.429 | −0.160 | ||||||||

| (1.207) | (0.407) | |||||||||

| Year effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Slope—low end | 3.4 | −2.7 | 13.8 | 8.2 | 3.5 | 11.1 | 5.0 | 4.2 | 6.0 | 1.9 |

| Slope—high end | −3.1 | 1.2 | −8.6 | −8.0 | −5.0 | −11.6 | −6.7 | −4.0 | −1.5 | −0.9 |

| Sasabuchi test stat. | 0.72 | .52 | 1.0 | 2.44 *** | 0.55 | 2.26 *** | 0.56 | 1.06 | 0.18 | 0.23 |

| Threshold (−β1/(2β2))/within data range | 5.2/no | 6.9/no | 6.2 | 5.1/yes | 4.1/no | 4.9/yes | 0.56/yes | 3.7/yes | 4.5 | 6.0/no |

| 95% Fieller interval for extreme point | -Inf/Inf. | -Inf/Inf. | -Inf/Inf. | 3.1/7.5 | -Inf/Inf. | 3.9/7.9 | -Inf/Inf. | -Inf/Inf. | -Inf/Inf. | -Inf/Inf. |

| Year effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | 51.44 | 50.20 * | 23.98 | 36.22 | 49.02 | 31.60 | 56.58 | 45.32 | 43.21 | 46.87 * |

| (42.58) | (27.02) | (46.03) | (26.50) | (45.77) | (28.91) | (41.92) | (29.02) | (43.56) | (25.46) | |

| Observations | 115 | 151 | 113 | 150 | 115 | 151 | 113 | 150 | 115 | 151 |

| R-squared | 0.099 | 0.217 | 0.129 | 0.226 | 0.097 | 0.240 | 0.115 | 0.215 | 0.098 | 0.211 |

| 1 | The number of mergers varies slightly in the regression results due to data availability. |

| 2 | These mergers were not included because ESG information is not available for SPACs. |

| 3 | In addition, we eliminated a few outliers where the deal premium was greater than 100. We also eliminated transactions where the target or acquirer ESG scores were less than 1. |

| 4 | For each company, E, S, and G are weighted based on all the environmental and social key issues as well as the governance pillar score. |

| 5 | In most mergers, 100% of the shares were acquired. |

| 6 | We also ran each of the models using quantile regression. The results from the quantile regression were very similar to the ones obtained using OLS. |

| 7 | |

| 8 | The difference in acquirer-to-target ESG (absolute value) was also weakly significant using the 1-week premium, but it was not quite significant using the 4-week premium. |

| 9 | The linear coefficient for acquirer governance is not quite significant at the 10 percent level when using the one and four-week deal premiums. The Sasabuchi test significant is significant for the one day and one week deal premium, but not for the four-week deal premium |

| 10 | We used the 2020 as our year. |

| 11 | The year-industry pair model (column 1)for estimating ESG did not pass the F-test. |

References

- Ahsan, T., & Qureshi, M. A. (2021). The nexus between policy uncertainty, sustainability disclosure and firm performance. Applied Economics, 53(4), 441–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktas, N., Bodt, E., & Cousin, J. G. (2011). Do financial markets care about SRI? Evidence from mergers and acquisitions. Journal of Banking and Finance, 35(7), 753–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandridis, G., Fuller, K. P., Terhaar, L., & Travlos, N. G. (2013). Deal size, acquisition premia and shareholder gains. Journal of Corporate Finance, 20, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandridis, G., Hoepner, A., Huang, Z., & Oikonomou, J. (2022). Corporate social responsibility culture and international M&As. The British Accounting Review, 54(1), 101035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benabou, R., & Tirole, J. (2010). Individual and corporate social responsibility. Economica, 77(305), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghesi, R., Chang, K., & Li, Y. (2019). Firm value in commonly uncertain times: The divergent effects of corporate governance and CSR. Applied Economics, 51(43), 4726–4741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner-Kirchmair, T. M., & Wagner, E. (2024). The impact of corporate social responsibility on the performance of mergers and acquisitions: European evidence. Cleaner Environmental Systems, 12, 100167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, G. (2015). Three essays on corporate social responsibility in merger and acquisition [Doctoral dissertation, Rutgers University-Graduate School-Newark]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X., Kang, J., & Low, B. (2013). Corporate social responsibility and stakeholder value maximization: Evidence from mergers. Journal of Financial Economics, 110(1), 87–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Waal, B. (2023). The influence of target ESG performance on premiums in mergers and acquisitions. Available online: https://thesis.eur.nl/pub/70071/Thesis-504623-Final.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Erben, S., Jost, S., Ottenstein, P., & Zülch, H. (2022). Does corporate social responsibility impact mergers & acquisition premia? New international evidence. Finance Research Letters, 46, 102237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairhurst, D. J., & Greene, D. (2022). Too much of a good thing? Corporate social responsibility and the takeover market. Journal of Corporate Finance, 73, 102172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X. (2021). The role of ESG in acquirers’ performance change after M&A deals. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5091721 (accessed on 16 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Pitman Publishing Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, M. (1970). A theoretical framework for monetary analysis. Journal of Political Economy, 78(2), 193–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giese, G., Lee, L.-E., Melas, D., Nagy, Z., & Nishikawa, L. (2019). Foundations of ESG investing: How ESG affects equity valuation. risk, and performance. Journal of Portfolio Management, 45(5), 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, P. C., Merrill, C. B., & Hansen, J. M. (2009). The relationship between corporate social responsibility and shareholder value: An empirical test of the risk management hypothesis. Strategic Management Journal, 30(4), 425–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, M., & Marsat, S. (2018). Does CSR impact premiums in M&A transactions? Finance Research Letters, 26, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haans, R., Pieters, C., & He, Z. (2016). Thinking about U: Theorizing and testing U- and inverted U-shaped relationships in strategy research. Strategic Management Journal, 37(7), 1177–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q., Li, Y., Lin, M., & McBrayer, G. A. (2022). Natural disasters, risk salience, and corporate ESG disclosure. Journal of Corporate Finance, 72, 102152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, T., & Shams, S. (2022). Pre-deal differences in corporate social responsibility and acquisition performance. International Review of Financial Analysis, 81, 102083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, M., Lee, J., & Wang, G. (2016). Does corporate social responsibility reduce information asymmetry? Evidence from the United States. Journal of Business Ethics, 125(4), 659–667. [Google Scholar]

- Jo, H., & Na, H. (2012). Does CSR reduce firm risk? Evidence from controversial industry sectors. Journal of Business Ethics, 110(4), 441–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanchel, I., & Lassoued, N. (2022). ESG disclosure and the cost of capital. Is there a ratcheting effect over time. Sustainability, 14(15), 9237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, H. R., Khidmat, W. B., Al Hares, O., Muhammad, N., & Saleem, K. (2020). Corporate governance quality, ownership structure, agency costs and firm performance: Evidence from an emerging economy. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 13(7), 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurti, C., Shams, S., Pensiero, D., & Velayutham, E. (2019). Socially responsible firms and mergers and acquisitions performance: Australian evidence. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 57, 101193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lind, J. T., & Mehlum, H. (2010). With or without U? The appropriate test for a U-shaped relationship. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 72(1), 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M., & Mamun, M. (2024). Impact of target firm’s social performance on acquisition premiums. Journal of Contemporary Accounting & Economics, 20, 100417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maung, M., Wilson, C., & Yu, W. (2020). Does reputation matter? Evidence from cross-border mergers and acquisitions. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 66, 101204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miralles-Quirós, M., Miralles-Quirós, J. L., & Gonçalves, L. M. V. (2018). The value relevance of environmental, social, and governance performance: The Brazilian case. Sustainability, 10(3), 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, J. R., & Aguinis, H. (2013). The too-much-of-a-good-thing effect in management. Journal of Management, 39(2), 313–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plumlee, M., Brown, D., Hayes, R. M., & Marshall, R. S. (2015). Voluntary environmental disclosure quality and firm value: Further evidence. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 34(4), 336–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M. E., & Kramer, M. R. (2006). The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. Harvard Business Review, 84(12), 78–92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- PwC. (2012). PwC annual report 2012. PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP. Available online: https://www.pwc.co.uk/assets/pdf/annual-report-2012.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Renneboog, L., Horst, J. T., & Zhang, C. (2008). Socially responsible investments: Institutional aspects, performance, and investor behavior. Journal of Banking & Finance, 32(9), 1723–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, A. J., & Welker, M. (2001). Social disclosure, financial disclosure and the cost of equity capital. Accounting Organizations Society, 26, 597–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasabuchi, S. (1980). A test of a multivariate normal mean with composite hypotheses determined by linear inequalities. Biometrika, 67(2), 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tampakoudis, I., & Anagnostopoulou, E. (2020). The effect of mergers and acquisitions on environmental, social and governance performance and market value: Evidence from EU acquirers. Business Strategy and the Environment, 29, 1865–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, N., Xu, X., Hsu, Y.-T., & Lin, C.-Y. (2024). The impact of ESG distance on mergers and acquisitions. International Review of Financial Analysis, 96, 103677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ung, T. A., & Urfe, M. N. (2021). ESG—Does it pay in M&A? Investigating the ESG premium in mergers and acquisitions [Master’s thesis, Norwegian School of Business]. Available online: https://openaccess.nhh.no/nhh-xmlui/bitstream/handle/11250/2766341/masterthesis.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- van Essen, M., Engelen, P. J., & Carney, M. (2013). Does “Good” corporate governance help in a crisis? The impact of country- and firm-level governance mechanisms in the European financial crisis. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 21(3), 201–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C., & Xie, F. (2009). Corporate governance transfer and synergistic gains from mergers and acquisitions. Review of Financial Studies, 22(2), 829–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., & Sonenshine, R. (2025). The nonlinear impact of ESG on stock market performance among US manufacturing and banking firms. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(6), 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whelan, T., Atz, U., Van Holt, T., & Clark, C. (2021). ESG and financial performance: Uncovering the relationship by aggregating evidence from 1000+ studies published between 2015–2020. NYU Stern Center for Sustainable Business and Rockefeller Asset Management. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Z., Li, J., Ren, X., & Guo, J. M. (2023). Does corporate ESG create value? New evidence from M&As in China. Pacific Basin Finance Journal, 77, 101916. [Google Scholar]

- Zrigui, M., Khanchel, I., & Lassoued, N. (2024). Does environmental, social and governance performance affect acquisition premium? Review of International Business and Strategy, 34(4), 469–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author(s) | Results | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Aktas et al. (2011) | Higher abnormal returns with targets that exhibit better CSR performance. | Acquirers learn from the practices of targets. |

| Deng et al. (2013) | Higher acquirer abnormal returns correspond to higher acquirer CSR performance | Acquirer’s social performance is the critical factor influencing merger returns and the likelihood that the merger is completed. |

| Tang et al. (2024) | Greater difference between ESG scores between acquirer and target results in lower abnormal returns. | Larger ESG differences increase the likelihood of merger integration problems and costs while reducing the likelihood of the merger being completed. |

| Malik and Mamun (2024) | Positive impact of a target’s CSR quality and the acquisition premiums, particularly for large targets and acquirers with high CSR performance. | CSR explains some of the variability in deal premiums. |

| Maung et al. (2020) | Lower deal premiums result from lower target ESG scores in cross-border mergers. | Deal premiums were lower for firms with ESG incidents reported in the media, particularly if the number of incidents was higher than those reported by the acquirer. |

| Brunner-Kirchmair and Wagner (2024) | CSR has a negative effect on abnormal returns in Europe. | Suggests “too much of a good thing,” meaning CSR activities may reduce a target’s value. |

| Erben et al. (2022) | Neither acquirer nor target ESG scores impact deal premiums, but acquirer governance interacting with ESG scores negatively impacts the premiums paid. Suggests a non-linear relationship between ESG and the deal premium. | Stronger governance practices by acquirers allow for a significant investment in CSR activities. |

| Hussain and Shams (2022) | The higher the bidder’s CSR scores relative to the target’s, the higher the combined cumulative abnormal returns of bidders and targets. | Synergies relate to differences in CSR scores between the acquirer and target |

| Alexandridis et al. (2022) | Differences in CSR scores resulted in lower announcement event returns. | Lower synergies due to a clash in cultures. |

| Fairhurst and Greene (2022) | Non-linear U-shaped relationship between CSR and the likelihood of a takeover and abnormal gains in takeovers. | Acquirers seek to gain by taking corrective action among firms with low CSR scores. Also, firms with high CSR scores are takeover targets due to the synergies of combining efforts. |

| Gomes and Marsat (2018) | Deal premiums are positively impacted by acquirer and target CSR; social scores only cause a premium in cross-border mergers, while environmental performance positively impacts premiums. | Lower information asymmetry. |

| Godfrey et al. (2009) | Deal premiums are positively impacted by higher target ESG scores. | ESG activities act as insurance in the event of a negative shock as high CSR levels reduce losses. |

| de Waal (2023) | Target ESG scores do not impact deal premiums. However, social scores have a positive impact, while governance scores have a negative impact. | Differential impact of social and governance scores lead to insignificant impact of ESG on deal premiums. |

| ESG Components | ESG Subcomponent and Weight |

|---|---|

| Environmental 1 | Climate change Natural capital (natural resource) Pollution and waste (waste management) Environmental opportunities |

| Social 2 | Human capital Product liability Stakeholder opposition Social opportunities |

| Governance 3 | Corporate governance Corporate behavior |

| Variable | Observations | Median | Mean | Standard Deviation | Range Min, Max | Mean Small Deals (<3696) | Mean Large Deals (>3696) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deal premium—1 day | 325 | 30.2 | 34.7 | 21.9 | 0.7, 96.5 | 35.5 | 34.3 |

| Deal premium—1 week | 331 | 32.0 | 36.4 | 23.0 | 0.2, 98.2 | 36.9 | 35.9 |

| Deal premium—1 month | 316 | 36.0 | 39.70 | 23.6 | 1, 99 | 39.5 | 39.2 |

| Deal value (in millions of USD) | 329 | 3696 | 6834 | 9853 | 100, 81,053 | 1655 | 12,012 |

| Target-Weighted ESG | 331 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.95 | 1.8, 8.0 | 4.87 | 5.16 |

| Target Governance | 331 | 5.9 | 5.6 | 1.62 | 0, 8.7 | 5.66 | 5.62 |

| Target Environmental | 331 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 2.69 | 0, 10.0 | 5.07 | 5.05 |

| Target Social | 331 | 4.6 | 4.6 | 1.57 | 0, 10.0 | 4.56 | 4.61 |

| Acquirer-Weighted ESG | 310 | 5.1 | 5.0 | 1.10 | 0.5, 8.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 |

| Acquirer Governance | 310 | 5.7 | 5.4 | 1.57 | 0, 8.8 | 5.4 | 5.4 |

| Acquirer Environmental | 310 | 5.5 | 5.5 | 2.43 | 0.7, 10.0 | 5.5 | 5.5 |

| Acquirer Social | 310 | 4.9 | 4.9 | 1.42 | 0.10 | 4.9 | 4.8 |

| Difference Current vs. Prior Target ESG | 252 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.33 | 0, 3.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Difference Current vs. Prior Acquirer ESG | 248 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.80 | 0, 5.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Difference Current vs. Prior (Acquirer–Target) ESG | 252 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.68 | 0, 5.4 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Relative Sales (Acquirer Sales/Target Sales) | 283 | 3.57 | 515 | 4044 | 0.02, 46,200 | 584 | 449 |

| Percent Competitive Bids | 283 | - | 17% | 0.36 | 0.100 | 14% | 18% |

| Percentage Completed | 283 | - | 88% | - | - | - | - |

| Percentage Shares Acquired | 283 | - | 87% | 0.29 | 0.100 | 84% | 89% |

| Percent Cash | 283 | - | 59% | 0.44 | 0.100 | 70% | 68% |

| Financial | 310 | - | 16% | - | - | - | - |

| Life Sciences | 310 | - | 16% | - | - | - | - |

| Technology | 310 | - | 13% | - | - | - | - |

| Industrial Goods | 310 | - | 11% | - | - | - | - |

| Services | 310 | - | 18% | - | - | - | - |

| Retail/Packaged Goods | 310 | - | 7% | - | - | - | - |

| Energy/Resources | 310 | - | 19% | - | - | - | - |

| Equation | Testable Variable(s) |

|---|---|

| Equation (2) (ESG term) |

|

| Equation (3) (Diff term) |

|

| Equation (4) (Diff_diff) |

|

| Response Variable 1-Day Deal Premium | Target ESG (1) | Acquirer ESG (2) | Acquirer–Target ESG Difference (3) | Current– Prior Year Target ESG Difference (4) | Current- Prior Year Acquirer ESG Difference (5) | Current-Prior Year Difference in (Acq.—Target) ESG (6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Log (dealvalue) | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.02 | 0.001 | 0.05 | 0.014 |

| (0.02) | (0.05) | (0.05) | (0.06) | (0.05) | (0.06) | |

| Percent cash | 0.004 *** | 0.003 *** | 0.004 *** | 0.004 *** | 0.004 *** | 0.004 *** |

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |

| Shares AcQ | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |

| Relative sales | 0.001 * | 0.001 | 0.001 * | 0.001 | 0.001 * | 0.001 |

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |

| completed | 0.0332 | −0.0202 | 0.027 | 0.02 | −0.007 | 0.02 |

| (0.172) | (0.165) | (0.171) | (0.187) | (0.180) | (0.193) | |

| competitive | 0.115 | 0.064 | 0.094 | 0.046 | 0.044 | 0.04 |

| (0.156) | (0.155) | (0.155) | (0.175) | (0.179) | (0.183) | |

| Target ESG | 0.812 ** | |||||

| (0.337) | ||||||

| Target ESG-squared | −0.077 ** | |||||

| (0.036) | ||||||

| Acquirer ESG | −0.16 | |||||

| (0.14) | ||||||

| Acquirer ESG-squared | 0.017 | |||||

| (0.02) | ||||||

| Abs Acquirer—Target | −0.16 | |||||

| ESG difference | (0.1) | |||||

| Abs Acquirer—Target | 0.04 * | |||||

| ESG difference-sq | (0.024) | |||||

| Current—Prior Target | 0.25 | |||||

| ESG difference | (0.24) | |||||

| Current—Prior Target | −0.14 * | |||||

| ESG difference-squared | (0.07) | |||||

| Current—Prior Acq. | 0.01 | |||||

| ESG difference | (0.17) | |||||

| Current—Prior Acq. | 0.01 | |||||

| ESG difference-squared | (0.03) | |||||

| Acquire—Target ESG (Current—Prior) | −0.11 (0.19) | |||||

| Acquire—Target ESG (Current—Prior) -squared | 0.04 (0.04) | |||||

| Year effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Slope—low end | 0.86 | 0.14 | −0.15 | 0.25 | −0.05 | −0.19 |

| Slope—high end | −0.46 | −0.11 | 0.40 | −1.39 | 2.7 | 0.51 |

| Sasabuchi test stat. | 1.67 ** | 0.86 | 1.36 * | 1.05 | 0.30 | 1.04 |

| Threshold (−β1/(2β2))/within data range | 5.27/yes | 4.75/yes | 1.75/yes | 0.88/yes | 0.88/yes | 1.62/yes |

| 95% Fieller interval for extreme point | 4.55; 13.6 | -Inf/inf | -inf, 15.9; 3.0, Inf | -Inf, 4.3/1.9, Inf | -Inf/inf | -Inf/inf |

| Observations | 275 | 279 | 270 | 241 | 235 | 229 |

| R-squared | 0.113 | 0.124 | 0.117 | 0.143 | 0.114 | 0.121 |

| Response Variable 1-Day Deal Premium | Small Deals Target ESG (1) | Large Deals/ Target ESG (2) | Small Deals/ Acq-Targ ESG (3) | Large Deals/ Acq-Targ ESG (4) | Small Deals/ Current-Prior Year Acquirer ESG (5) | Large Deals/ Current-Prior Year Acquirer ESG (6) | Small Deals/ Acquire—Target ESG (Current–Prior Year) (7) | Large Deals/ Acquire—Target ESG (Current–Prior Year) (8) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Log (dealvalue) | −5.383 | −3.123 | −4.692 | −2.316 | −5.056 | −2.335 | −3.517 | −2.381 |

| (3.34) | (2.56) | (3.29) | (2.60) | (3.49) | (2.82) | (3.74) | (2.79) | |

| Percent cash | 0.0503 | 0.118 *** | 0.064 | 0.109 *** | 0.089 * | 0.093 ** | 0.096 * | 0.094 ** |

| (0.04) | (0.03) | (0.05) | (0.04) | (0.05) | (0.04) | (0.05) | (0.04) | |

| Shares AcQ | −0.021 | −0.014 | −0.004 | −0.010 | −0.050 | −0.075 | −0.044 | −0.072 |

| (0.09) | (0.07) | (0.10) | (0.07) | (0.09) | (0.08) | (0.10) | (0.09) | |

| Relative sales | 0.000 | 0.001 ** | 0.000 | 0.001 ** | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 ** | 0.001 ** |

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |

| Completed | −0.339 | 4.895 | 3.183 | 4.732 | 2.829 | 4.932 | 3.499 | 4.579 |

| (7.89) | (5.19) | (8.25) | (5.19) | (8.04) | (5.83) | (8.30) | (5.91) | |

| competitive | −1.809 | 11.93 ** | 0.0619 | 12.30 ** | −0.759 | 13.83 ** | −1.287 | 14.20 ** |

| (6.28) | (4.95) | (6.95) | (4.90) | (7.51) | (5.55) | (7.24) | (5.88) | |

| Target ESG | 29.63 ** | 32.74 *** | ||||||

| (11.86) | (9.832) | |||||||

| Target ESG2 | −2.845 ** | −3.197 *** | ||||||

| (1.236) | (1.039) | |||||||

| Acquirer—Targ | −10.95 | −0.034 | ||||||

| ESG difference | (8.575) | (4.271) | ||||||

| Acquirer—Targ | 3.240 | 0.135 | ||||||

| ESG difference-sq | (2.792) | (0.793) | ||||||

| Current—Prior | −13.11 | 3.602 | ||||||

| Acq ESG diff | (10.38) | (6.41) | ||||||

| Current- Prior | 5.384 * | −0.662 | ||||||

| Acq ESG diff-sq | (3.17) | (1.24) | ||||||

| Acq—Target ESG | −32.77 *** | 3.365 | ||||||

| (Current—Prior) | (11.72) | (6.921) | ||||||

| Acq—Target | 14.49 ** | −0.647 | ||||||

| (Current—Prior)-sq | (5.568) | (1.382) | ||||||

| Year effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | 7.101 | 26.93 | 68.19 ** | 37.47 | 77.84 ** | 44.54 | 55.68 * | 44.17 |

| (36.37) | (27.21) | (28.84) | (23.84) | (31.16) | (27.09) | (30.72) | (27.02) | |

| Slope—low end | 29.6 | 32.7 | −11.24 | −1.35 | −13.4 | 3.6 | −32.5 | −2.1 |

| Slope—high end | −15.8 | −18.4 | 26.83 | 3.53 | 47.4 | −4.1 | 136.5 | 4.7 |

| Sasabuchi test stat. | 1.92 ** | 2.53 *** | 1.09 | 0.31 | 1.26 * | 0.53 | 2.49 ** | 0.30 |

| Threshold (−β1/(2β2))/within data range | 5.2/yes | 5.15 | 1.84/yes | 1.72/no | 1.22/yes | 2.72/yes | 1.13/yes | 1.78/yes |

| 95% Fieller interval for extreme point | 4.5/8.5 | 4.4/6.4 | -Inf/Inf | -Inf/Inf | -Inf/Inf | -Inf/Inf | 0.78/1.94 | -Inf/Inf |

| Observations | 128 | 156 | 120 | 150 | 111 | 128 | 106 | 127 |

| R-squared | 0.196 | 0.284 | 0.173 | 0.252 | 0.162 | 0.189 | 0.182 | 0.184 |

| Response Variable 1-Day Deal Premium | Small Deals Target Env (1) | Large Deals Target Env (2) | Small Deals Acq Social (3) | Large Deals Acq Social (4) | Small Deals Target Social (5) | Large Deals Target Social (6) | Small Deals Acq Gov (7) | Large Deals Acq Gov (8) | Small Deals Target Gov (9) | Large Deals Target Gov (10) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ldealvalue | −5.722 * | −1.842 | −5.310 * | −2.264 | −5.469 * | −3.309 | −5.056 | −2.66 | −6.327 * | −2.455 |

| (3.17) | (2.62) | (2.97) | (2.710) | (3.22) | (2.61) | (3.49) | (2.57) | (3.20) | (2.61) | |

| percentcash | 0.0272 | 0.115 *** | 0.0795 * | 0.108 *** | 0.0498 | 0.109 *** | 0.081 * | 0.110 *** | 0.0295 | 0.108 *** |

| (0.05) | (0.04) | (0.04) | (0.0387) | (0.05) | (0.04) | (0.05) | (0.04) | (0.04) | (0.04) | |

| Relative sales | 0.000 | 0.001 ** | 0.000 | 0.001 ** | 0.000 | 0.000 | −11.67 * | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 ** |

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (6.25) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |

| completed | 2.475 | 5.239 | 3.828 | 4.368 | 2.69 | 5.282 | 4.310 | 5.245 | 0.89 | 4.973 |

| (7.58) | (5.04) | (7.66) | (5.01) | (7.96) | (5.48) | (7.44) | (5.51) | (7.43) | (5.26) | |

| competitive | −0.562 | 12.23 ** | −0.336 | 12.24 ** | 0.527 | 12.93 *** | 0.000 | 13.44 *** | 0.0801 | 12.61 ** |

| (6.23) | (4.78) | (6.61) | (4.91) | 6.23) | (4.84) | (0.00) | (4.93) | (6.05) | (5.17) | |

| sharesAQ | −0.004 | −0.009 | −0.009 | −0.011 | −0.014 | −0.018 | 2.83 | −0.032 | 0.008 | −0.014 |

| (0.09) | (0.08) | (0.09) | (0.07) | (0.09) | (0.07) | (8.04) | (0.07) | (0.09) | (0.07) | |

| Target Environ. | 5.460 * | −2.161 | ||||||||

| (3.166) | (2.702) | |||||||||

| Target Environ-sq | −0.333 | 0.158 | ||||||||

| (0.321) | (0.248) | |||||||||

| Acq Social | 7.531 | 5.291 * | ||||||||

| (7.706) | (3.038) | |||||||||

| Acq Social-squared | −0.747 | −0.399 | ||||||||

| (0.797) | (0.324) | |||||||||

| Target Social | −0.030 | 8.67 *** | ||||||||

| (4.166) | (3.10) | |||||||||

| Target Social-sq | 0.104 | −0.722 * | ||||||||

| (0.448) | (0.401) | |||||||||

| Acq Gover | 8.030 | 5.226 * | ||||||||

| (5.271) | (3.084) | |||||||||

| Acq Gover-squared | −0.787 | −0.604 * | ||||||||

| (0.552) | (0.368) | |||||||||

| Targ Gover | 21.32 ** | −0.441 | ||||||||

| (8.493) | (3.523) | |||||||||

| Targ Gover-sq | −1.896 ** | 0.110 | ||||||||

| (0.800) | (0.393) | |||||||||

| Year effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Slope—low end | 5.46 | −2.63 | 8.55 | 5.3 | 0.1 | 8.0 | 7.9 | 5.22 | 21.3 | 1.75 |

| Slope—high end | −1.18 | 1.62 | −8.00 | 2.7 | 2.16 | −5.8 | −6.4 | −5.40 | −11.6 | −0.51 |

| Sasabuchi test stat. | 0.34 | 0.66 | 1.09 | 0.71 | - | 1.11 | 1.21 | 1.48 * | 2.05 ** | 0.13 |

| Threshold (−β1/(2β2))/within data range | 7.94/no | 6.18/no | 5.17/yes | 6.62/yes | −0.58/no | 6.0/yes | 5.1/yes | 4.3/yes | 5.61/yes | 6.72/no |

| 95% Fieller interval for extreme point | -Inf 5.3/1.53inf | -Inf/Inf | -Inf/Inf | 0.33/19.1 | -Inf/Inf | -Inf/-inf | -Inf/Inf | −0.49/6.77 | 7.66/8.19 | -Inf/Inf |

| Constant | 55.15 ** | 37.63 | 44.02 | 32.93 | 66.23 ** | 30.12 | 81.78 ** | 35.72 | 45.85 | 33.44 |

| −27.4 | −24.54 | −30.43 | −25.34 | −28.97 | −25.06 | −31.97 | −25.85 | (29.22) | −23.91 | |

| Observations | 128 | 156 | 125 | 154 | 128 | 156 | 112 | 154 | 128 | 156 |

| R-squared | 0.205 | 0.256 | 0.172 | 0.264 | 0.163 | 0.285 | 0.161 | 0.166 | 0.151 | 0.153 |

| 1st Stage | 1st Stage | 1st Stage | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimating | Estimating | Estimating | ||||

| ESG | 1-Day Premium | ESG | 1-Day Premium | ESG | 1-Day Premium | |

| ESG | 11.12 | 36.59 * | 21.88 *** | |||

| (16.88) | (21.46) | (8.392) | ||||

| ESG-squared | −2.505 *** | −2.555 *** | −2.493 *** | |||

| (0.728) | (0.729) | (0.721) | ||||

| Twenty0 | −0.611 * | −5.968 | −0.519 *** | 7.259 | −1.986 *** | 0.0623 |

| (0.340) | (9.195) | (0.164) | (10.93) | (0.533) | (5.295) | |

| Twenty1 | −0.437 ** | 1.151 | −0.451 *** | 11.59 | −0.365 ** | 5.936 |

| (0.174) | (7.818) | (0.174) | (9.898) | (0.169) | (4.932) | |

| Twenty2 | −0.379 ** | 4.078 | −0.325 * | 12.67 | −0.344 ** | 7.853 |

| (0.179) | (6.993) | (0.176) | (7.818) | (0.169) | (5.168) | |

| Twenty3 | −0.477 ** | 5.959 | −0.476 ** | 17.25 | −0.236 | 11.59 ** |

| (0.188) | (8.948) | (0.185) | (10.56) | (0.173) | (5.360) | |

| Industry | Not Sig | Not Sig | Not Sig | Not Sig | Not Sig | Not Sig |

| Residual (Year–Industry) | 14.66 (15.25) | |||||

| Year–Industry | Not Sig | |||||

| (0.433) | ||||||

| US–Finance | −0.849 *** | 4.154 | ||||

| (0.252) | (18.30) | |||||

| US–Other Industries | Not Sig | |||||

| Residual (Region–Industry) | −10.73 (20.10) | |||||

| Regions | Not Sig | |||||

| Twenty0—US | 1.541 *** | 8.782 | ||||

| (0.536) | (23.91) | |||||

| Twenty0—EU | 1.479 *** | 16.98 | ||||

| (0.559) | (26.15) | |||||

| Twenty0—Asia | 1.164 * | 25.15 | ||||

| (0.637) | (25.21) | |||||

| Residual (Year–Region) | 3.794 (5.993) | |||||

| F-test | 1.35 | 2.01 ** | 4.18 *** | |||

| Observations | 336 | 276 | 336 | 276 | 378 | 275 |

| R-squared | 0.064 | 0.141 | 0.093 | 0.141 | 0.070 | 0.153 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sonenshine, R.; Wang, Y. Non-Linear Impact of Environmental, Social, and Governance Scores on Deal Premiums. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 599. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18110599

Sonenshine R, Wang Y. Non-Linear Impact of Environmental, Social, and Governance Scores on Deal Premiums. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(11):599. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18110599

Chicago/Turabian StyleSonenshine, Ralph, and Yan Wang. 2025. "Non-Linear Impact of Environmental, Social, and Governance Scores on Deal Premiums" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 11: 599. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18110599

APA StyleSonenshine, R., & Wang, Y. (2025). Non-Linear Impact of Environmental, Social, and Governance Scores on Deal Premiums. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(11), 599. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18110599