Mitigating Tax Evasion by improving the organizational structure of VAT on Digital Imports into South Africa

Abstract

1. Introduction

“The VAT that broke The Budget.”

- Section 1 definitions: “supply”; “imported services”; “open market value”.

- Section 3: determination of “open market value”.

- Section 7(1)(c): imposition of VAT on imported services by any person.

- Section 14: collection of VAT on imported services, determination of value and exemptions; read with Section 10(2) and (3): general value of supply rule; and Section 3: determination of open market value.

- Section 1 definitions: “electronic services”; “enterprise”—paragraph (b)(vi); “export country”; “services”; “supply”.

- Section 7(1)(a): imposition of VAT on the sale of goods or services.

- Section 7(1)(c): imposition of VAT on imported services by any person; read with Section 14(5)(a): exceptions to imposition of VAT on imported services by any person.

- Section 23(1A): registration requirements for suppliers of electronic services.

- Section 16(2)(b), read with Section 20(7): input tax and documentary requirements.

- Government Notice No. 429 published in Government Gazette No. 4231: regulations with respect to electronic services.

- Alongside the provisions of the VAT Act, vendors must additionally refer to the following guidance papers provided by the South African Revenue Service (SARS) to thoroughly understand the VAT requirements related to the provision of electronic services in South Africa: SARS Frequently Asked Questions: Supplies of Electronic Services (South African Revenue Service, 2019a); SARS External Guide: Foreign Suppliers of Electronic Service (South African Revenue Service, 2022a); and Binding General Ruling No. 28: Electronic Services (South African Revenue Service, 2016).

2. Literature Review

2.1. Tax Complexity

2.2. General Literature: Legal Complexity and Logical Structure

2.3. Findings from the Literature: Scattered Sections of the VAT Act

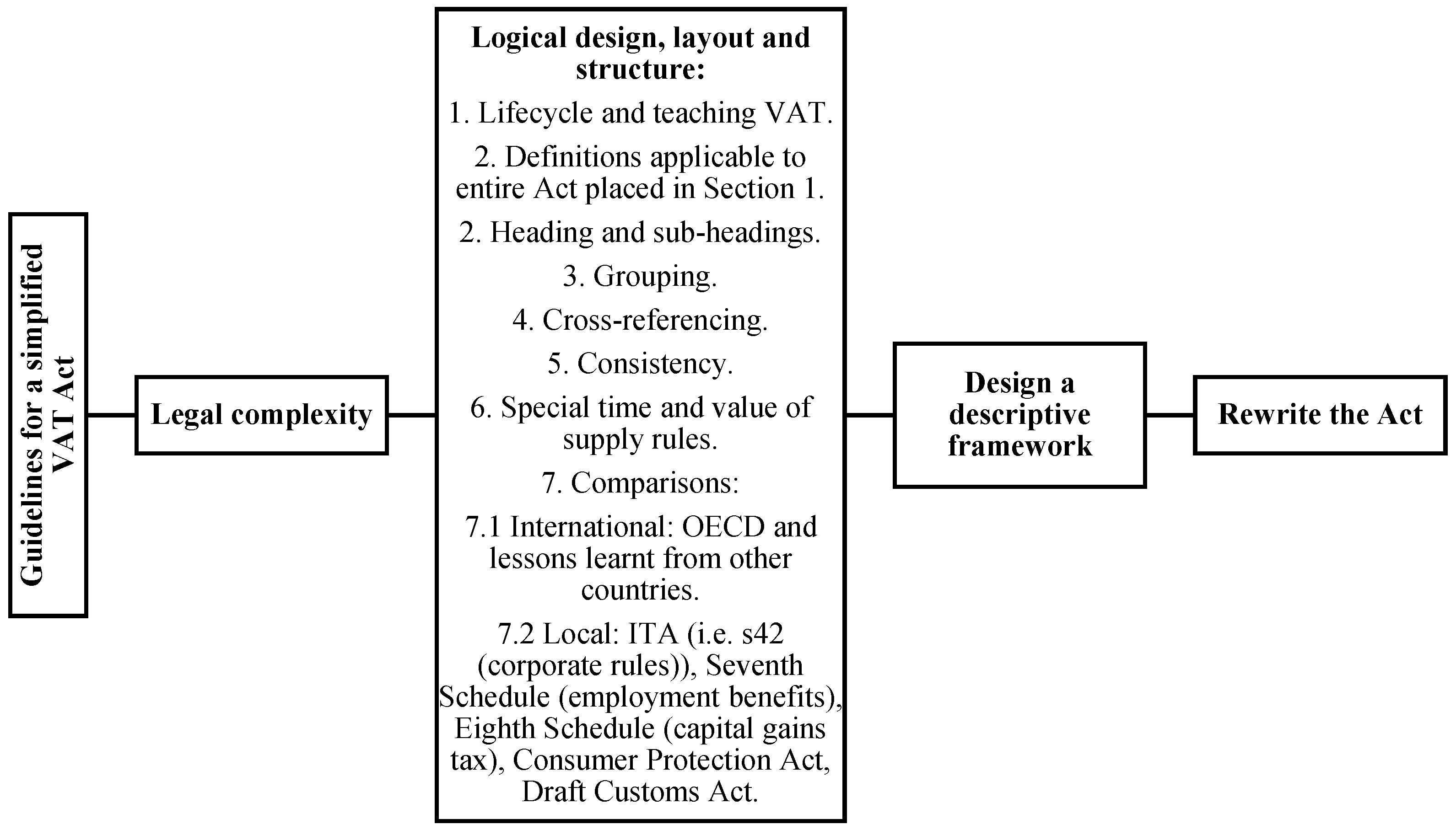

One radical suggestion has been that the Act should be re-written and re-structured in its entirety. Such a rewrite would undoubtedly result in a rearrangement of the provisions of the Act into a more coherent logical sequence. This may enhance the efficiency of the compliance environment of taxpayers.[Emphasis added.]

Cross-references between sections also abound, making the interpretation of the sections extremely complex. Section 16(3) of the VAT Act includes fourteen subsections, some with numerous sub-subsections and provisos, each of which is cross-referenced to a different section in the Act.

2.4. The General Literature: Principles of Logical Structure

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. Imported Services

4.1.1. Summary of VAT Implications

4.1.2. The Law

- Section 1 definitions: “supply”; “imported services”; “open market value”.

- Section 3, determination of “open market value”.

- Section 7(1)(c).

- Section 14, read with Section 10(2) and (3), and Section 3.

4.1.3. Analysis and Interpretation

Imposition of value-added tax.—(1) Subject to the exemptions, exceptions, deductions and adjustments provided for in this Act, there shall be levied and paid for the benefit of the National Revenue Fund a tax, to be known as the value-added tax—(a) …(b) …(c) on the supply of any imported services by any person on or after the commencement date,calculated at the rate of 15 per cent on the value of the supply concerned or the importation, as the case may be.

… a supply of services that is made by a supplier who is resident or carries on business outside the Republic to a recipient who is a resident of the Republic to the extent that such services are utilized or consumed in the Republic otherwise than for the purpose of making taxable supplies;

Examples of when a resident recipient has to account for VAT on imported services are where the recipient–

- Section 1 definitions: “supply”; “imported services”; “open market value”.

- Section 3: determination of “open market value”.

- Section 7(1)(c): imposition of VAT on imported services by any person.

- Section 14: collection of VAT on imported services, determination of value and exemptions, read with Section 10(2) and (3) (general value of supply rule), and Section 3 (determination of open market value).

- Facts

- b.

- Issue

- (i)

- Whether the tax court was correct in finding that SARS was entitled to disallow Consol’s claim for input tax on fees charged by local service providers;

- (ii)

- Whether the tax court was correct in finding that Consol was required to declare and pay VAT on fees paid by Consol to foreign service providers who supplied services to it.

- c.

- Arguments by SARS

- d.

- Arguments by Consol

- e.

- Judgement

- f.

- Commentary

- g.

- Linking the court case to the scattered sections in the VAT Act

4.2. Electronic Services

4.2.1. Summary of the VAT Implications

4.2.2. The Law

- Section 1 definitions: “electronic services”; “enterprise” (paragraph (b)(vi)); “export country”; “services”; “supply”.

- Section 7(1)(a).

- Section 7(1)(c) read with Section 14(5)(a).

- Section 23(1A).

- Section 16(2)(b) read with Section 20(7).

- Government Notice No 429 published in Government Gazette No. 42316 (the new rules).

4.2.3. Analysis and Interpretation

- (i)

- (ii)

- (iii)

- Complete the VAT101—Application for Registration for Value Added Tax—External Form (VAT Application Form);

- Complete the VAT 201—VAT Vendor Declaration (VAT201);

- File the VAT201 and make the VAT payment;

- Request a VAT registration to be cancelled, where the value of electronic services supplied has not exceeded the threshold of ZAR 1 million in a period of 12 months.

- Section 1 definitions: “electronic services”; “enterprise” (paragraph (b)(vi)); “export country”; “services”; “supply”.

- Section 7(1)(a): imposition of VAT on the sale of goods or services.

- Section 7(1)(c): imposition of VAT on imported services by any person, read with Section 14(5)(a) (exceptions to imposition of VAT on imported services by any person).

- Section 23(1A): registration requirements for suppliers of electronic services.

- Section 16(2)(b) read with Section 20(7) (input tax and documentary requirements).

- Government Notice No 429 published in Government Gazette No. 42316 (the new rules) (regulations in respect of electronic services).

4.3. Guidelines to Simplify the VAT Act

4.4. Implementation of the Guidelines

- Frequently Asked Questions Regarding Electronic Services Supplies (South African Revenue Service, 2019a).

- SARS External Guide: International Providers of Electronic Services (South African Revenue Service, 2022a).

- Binding General Ruling No. 28: Electronic Services (South African Revenue Service, 2016).

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abidar, B., Ed-Dafali, S., & Kobiyh, M. (2025). Determinants of value-added tax revenue transfers in municipalities of emerging economies. Economies, 13(5), 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Asfour, F., & McGee, R. W. (2024). Tax evasion and tax compliance: What have we learned from the 100 most cited studies? In R. W. McGee, & J. Shopovski (Eds.), The ethics of tax evasion: Vol. 2: New perspectives in theory and practice (pp. 1–23). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Alshira’h, A. F., Alshirah, M. H., & Lutfi, A. (2025). Forensic accounting, socio-economic factors and value added tax evasion in emerging economies: Evidence from Jordan. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting, 23(1), 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Institute of Certified Public Accountants. (2001). Tax policy concept: Guiding principles of good tax policy: A framework for evaluating tax proposals. Author. [Google Scholar]

- Besanko, M., Govender, G., & Swanepoel, J. (2021). Tax alert: Functional link required between costs incurred and taxable supplies. PwC. Available online: https://taxfaculty.ac.za/news/read/another-vat-hurdle (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Brodsky, A., Welsh, E., Hoffman, R., Deffenbacher, K., & Nye, F. (2008). Applied research. In The Sage encyclopedia of qualitative research methods. Sage. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budak, T., & James, S. (2018). The level of tax complexity: A comparative analysis between the UK and Turkey based on the OTS index. International Tax Journal, 44(1), 23–36. [Google Scholar]

- Caldeira, E., Compaore, A., Dama, A. A., Mansour, M., & Rota-Graziosi, G. (2019). Effort fiscal en afrique subsaharienne: Les résultats d’une nouvelle base de données [Tax effort in Sub-Saharan Africa: Results from a new database]. Revue D’économie du Développement, 27(4), 5–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W., & Jin, R. (2023). Does tax uncertainty affect firm innovation speed? Technovation, 125, 102771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins online dictionary. (2023). Available online: http://www.collinsdictionary.com/english/ (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Crabbe, V. (1993). Legislative drafting. Cavendish. [Google Scholar]

- Cutts, M. (2013). Oxford guide to plain English. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dale, W. (1977). Legislative drafting: A new approach. Butterworths. [Google Scholar]

- Davis Tax Committee. (2018). Report on the efficiency of South Africa’s corporate tax system. Available online: https://www.taxcom.org.za/docs/20180411%20Final%20DTC%20CIT%20Report%20-%20to%20Minister.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- De La Feria, R., & Schoeman, A. (2019). Addressing VAT fraud in developing countries: The tax policy-administration symbiosis. Intertax: International Tax Review, 47(11), 950–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wet, C., & Moonsamy, S. (n.d.). The Consol Glass case: A primer for claiming input tax and liability for imported services? ENSafrica. Available online: https://www.ensafrica.com/news/detail/3757/the-consol-glass-case-a-primer-for-claiming-i (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Diver, C. S. (1983). The optimal precision of administrative rules. Yale Law Journal, 93, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodwell, B. (2021, January 20). The OTS: The story so far. Tax Journal. Available online: https://www.taxjournal.com/articles/the-ots-the-story-so-far- (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Eloundou, G. N., Beyene, B. O., & Nkoa, B. E. O. (2025). On the path to accelerating industrialisation in Africa: The role of fiscal decentralisation. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, R. (1997). Simple rules for a complex world. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Givati, Y. (2009). Resolving legal uncertainty: The fulfilled promise of advance tax rulings. Vaginia Tax Review, 29, 137. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Canada. (2025). Confirming a simplified GST/HST account number. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/services/tax/businesses/topics/gst-hst-businesses/digital-economy-gsthst/confirming-simplified-gst-hst-account-number.html (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Hassan, M. E., Bornman, M., & Sawyer, A. (2024). Guidelines for a simplified Value-Added Tax Act. South African Journal of Accounting Research, 38(3), 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hern Kuan, L., & Ooi, V. (2019). Proposed reforms to Singapore’s Goods and Services Tax for the digital age. Tax Notes International, 93(5), 521–530. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, B. (2002). Plain language in legislative drafting: Is it really the answer? Statute Law Review, 23(1), 24–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, T., & Duncan, N. (2012). Defining and describing what we do: Doctrinal legal research. Deakin Law Review, 17(1), 83–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales. (2024). Why previous efforts to simplify VAT have failed. Available online: https://www.icaew.com/insights/tax-news/2024/nov-2024/why-previous-efforts-to-simplify-vat-have-failed (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Kamasa, K., Nortey, D. N., Boateng, F., & Bonuedi, I. (2025). Impact of tax reforms on revenue mobilisation in developing economies: Empirical evidence from Ghana. Journal of Economic and Administrative Sciences, 41(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, D. M., & Bommarito, M. J. (2014). Measuring the complexity of the law: The United States code. Artificial Intelligence and Law, 22, 337–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keen, M., & Smith, S. (1996). The future of value-added tax in the European Union. Economic Policy, 23, 373–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimble, J. (1996). Writing for dollars, writing to please. The Scribes Journal of Legal Writing 6, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Moodaley, V. (2020). VAT on imported services payable by non-registered VAT vendors and goods sold in execution: The who, what and how of declarations to SARS. Cliffe Dekker Hofmeyr. Available online: https://www.cliffedekkerhofmeyr.com/news/publications/2020/tax/tax-alert-4-june-VAT-on-imported-services-payable-by-non-registered-VAT-vendors-and-goods-sold-in-execution-the-who-what-and-how-of-declarations-to-SARS.html (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- National Treasury. (2013). Taxation laws amendment act no. 31 of 2013. Available online: https://www.gov.za/documents/taxation-laws-amendment-bill-13 (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- National Treasury. (2018). Rates and monetary amounts and amendment of revenue laws act, 2018. Government Printer.

- National Treasury. (2019). Regulation No. 429—Value-added tax act, 1991: Regulations prescribing electronic services for the purpose of the definition of “Electronic Services” in section 1 of the act, notice No: 42316. Government Printer.

- Office of Tax Simplification. (2017). Office of tax simplification complexity index paper 2017. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a82ab43ed915d74e3402f66/OTS__complexity_index_paper_2017.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Office of Tax Simplification. (2022). Update on the closure of the office of tax simplification. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/update-on-the-closure-of-the-office-of-tax-simplification (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Onana, S. P., & Mamoho, T. L. (2025). The determinants of the distribution of the public investment budget between the decentralized territorial communities: Evidence from Cameroon. Economia Politica, 42, 339–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, J. (2025). GST update: Key legislative amendments. Grant Thornton. Available online: https://www.grantthornton.sg/insights/2025-insights/gst-update-key-legislative-amendments/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Pau, C., Sawyer, A., & Maples, A. (2007). Complexity of the New Zealand’s tax laws: An empirical study. Australian Tax Forum, 22(2), 59–92. [Google Scholar]

- Petelin, R. (2010). Considering plain language: Issues and initiatives. Corporate Communications, 15(2), 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinskaya, M. R., Milogolov, N. S., Yarullin, R. R., & Mitin, D. A. (2022). VAT taxation of electronic services in Russia in the context of principles of international neutrality and simplicity. In E. G. Popkova (Ed.), Business 4.0 as a subject of the digital economy (pp. 619–623). Springer International. [Google Scholar]

- Republic of South Africa. (1991). Value-added tax act (Act No. 89 of 1991) (as amended). Government Printer.

- Republic of South Africa. (2011). Tax administration act (Act No. 28 of 2011) (as amended). Government Printer.

- Richardson, M., & Sawyer, A. (1998). Complexity in the expression of New Zealand tax laws: An empirical analysis. Australian Tax Forum, 14(3), 325–360. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, S. I., Friedman, W. H., Ginsburg, M. D., & Louthan, C. T. (1971). A report on complexity and the income tax. Tax Law Review, 27, 325. [Google Scholar]

- Saw, K. S. L., & Sawyer, A. (2010). Complexity of New Zealand’s income tax legislation: The final instalment. Australian Tax Forum, 25(2), 213–245. [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer, A. (2013). Reviewing tax policy development in New Zealand: Lessons from a delicate balancing of ‘law and politics’. Australian Tax Forum, 28(2), 401–425. [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer, A. (2016). Complexity of tax simplification: A New Zealand perspective. In S. James, A. Sawyer, & T. Budak (Eds.), The complexity of tax simplification (pp. 110–132). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer, A. (2023). Vale the office of tax simplification: Is its abolition an ill-informed decision? British Tax Review, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer, A. J., Bornman, M., & Smith, G. (2019). Simplification: Lessons from New Zealand. In C. Evans, R. Franzsen, & E. Stack (Eds.), Tax simplification: An African perspective (pp. 123–159). Pretoria University Law Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Smaill, G. (2021). Taxation law drafting review and recommendations. Greenwood Roche Project Lawyers. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, D., & Richardson, G. (1999). The readability of Australia’s taxation laws and supplementary materials: An empirical investigation. Fiscal Studies, 20(3), 321–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South African Revenue Service. (2016). Binding general ruling (VAT): No. 28 (Issue 2), electronic services. Available online: https://www.sars.gov.za/wp-content/uploads/Legal/Archive/BGRs/Legal-Arc-BGR-28-02-Electronic-Services-Issue-2-archived-10-February-2023.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- South African Revenue Service. (2019a). Legal council: Value-added tax. Frequently asked questions: Supplies of electronic services. Available online: https://www.sars.gov.za/wp-content/uploads/Ops/Guides/LAPD-VAT-G16-VAT-FAQs-Supplies-of-electronic-services.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- South African Revenue Service. (2019b). VAT 404 guide for vendors. Available online: https://www.sars.gov.za/wp-content/uploads/Ops/Guides/Legal-Pub-Guide-VAT404-VAT-404-Guide-for-Vendors.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- South African Revenue Service. (2021). Interpretation notes. Available online: https://www.sars.gov.za/legal-counsel/legal-counsel-archive/interpretation-notes/ (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- South African Revenue Service. (2022a). SARS external guide: Foreign suppliers of electronic service. Available online: https://www.sars.gov.za/wp-content/uploads/Ops/Guides/VAT-REG-02-G02-Foreign-Suppliers-of-Electronic-Services-External-Guide.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- South African Revenue Service. (2022b). VAT regulations on domestic reverse charge relating to valuable metal. Available online: https://www.sars.gov.za/types-of-tax/value-added-tax/vat-regulations-on-domestic-reverse-charge-relating-to-valuable-metal/ (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- South African Revenue Service. (n.d.). Find a guide. Available online: https://www.sars.gov.za/legal-counsel/legal-counsel-publications/find-a-guide/ (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Surrey, S. S. (1969). Complexity and the internal revenue code: The problem of the management of tax detail. Law and Contemporary Problems, 34(4), 673–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L. M., & Tower, G. (1992). The readability of tax laws: An empirical study in New Zealand. Australian Tax Forum, 9(3), 355–372. [Google Scholar]

- Thuronyi, V. (1996). Tax law design and drafting: Volume 1. International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Tran-Nam, B. (1999). Tax reform and tax simplification: Some conceptual issues and a preliminary assessment. The Sydney Law Review, 21(3), 500–522. [Google Scholar]

- Van Hoecke, M. (2011). Legal doctrine: Which method(s) for what kind of discipline? In M. van Hoecke (Ed.), Methodologies of legal research: Which kind of method for what kind of discipline? (pp. 1–18) Hart. [Google Scholar]

- Van Niekerk, R. (2025, February 19). The VAT that broke The Budget. Moneyweb. Available online: https://www.moneyweb.co.za/moneyweb-opinion/columnists/the-vat-that-broke-the-budget/ (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Young, G. J. (2021). An analysis of ways in which the South African tax system could be simplified [Unpublished master’s dissertation, Rhodes University]. [Google Scholar]

| 1. Definitions |

| 2. Financial services |

| 3. Determination of “open market value” |

| PART I |

| Administration |

| 4. Administration of Act |

| 5. Exercise of powers and performance of duties |

| 6. … |

| PART II |

| Value-added tax |

| 7. Imposition of value-added tax |

| 8. Certain supplies of goods or services deemed to be made or not made |

| 8A. Shariah-compliant financing arrangements |

| 9. Time of supply |

| 10. Value of supply of goods or services |

| 11. Zero rating |

| 12. Exempt supplies |

| 13. Collection of tax on importation of goods, determination of value thereof and exemptions from tax |

| 14. Collection of value-added tax on imported services, determination of value thereof and exemptions from tax |

| 15. Accounting basis |

| 16. Calculation of tax payable |

| 17. Permissible deductions in respect of input tax |

| 18. Change in use adjustments |

| 18A. Adjustments in consequence of acquisition of going concern wholly or partly for purposes other than making taxable supplies |

| 18B. Temporary letting of residential fixed property |

| 18C. Adjustments for leasehold improvements |

| 18D. Temporary letting of residential property |

| 19. Goods or services acquired before incorporation |

| 20. Tax invoices |

| 21. Credit and debit notes |

| 22. Irrecoverable debts |

| PART III |

| Registration |

| 23. Registration of persons making supplies in the course of enterprises |

| 24. Cancellation of registration |

| 25. Vendor to notify change of status |

| 26. Liabilities not affected by person ceasing to be vendor |

| Example: Electronic Services Supplied by Non-Residents | |

|---|---|

| Definitions | Section 1 definition of “electronic services”, “enterprise” paragraph (b)(vi), “export country”, “services”, “supply” |

| Scope (output) | Section 7(1)(c) read with Section 14(5)(a); Section 7(1)(a) read with Section 23(1A) [Binding General Ruling 28, Notice.429] |

| Time of supply | Section 9(1) |

| Value of supply | Section 10(2) |

| Scope (input) | Section 16(2)(b) read with Section 20(7) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hassan, M. Mitigating Tax Evasion by improving the organizational structure of VAT on Digital Imports into South Africa. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 574. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18100574

Hassan M. Mitigating Tax Evasion by improving the organizational structure of VAT on Digital Imports into South Africa. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(10):574. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18100574

Chicago/Turabian StyleHassan, Muneer. 2025. "Mitigating Tax Evasion by improving the organizational structure of VAT on Digital Imports into South Africa" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 10: 574. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18100574

APA StyleHassan, M. (2025). Mitigating Tax Evasion by improving the organizational structure of VAT on Digital Imports into South Africa. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(10), 574. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18100574