Drivers of Blockchain Adoption in Accounting and Auditing Services: Leveraging Theory of Planned Behavior with Identity and Moral Norms

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (RQ1) What role do traditional TPB constructs (Attitude, subjective norm, and Perceived Behavioral Control) play in predicting blockchain adoption in accounting and auditing?

- (RQ2) How do self-identity and personal moral norms extend TPB’s explanatory power in this context?

- (RQ3) Which factor emerges as the strongest driver of adoption intention among professionals?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Blockchain Technology and Its Transformative Potential

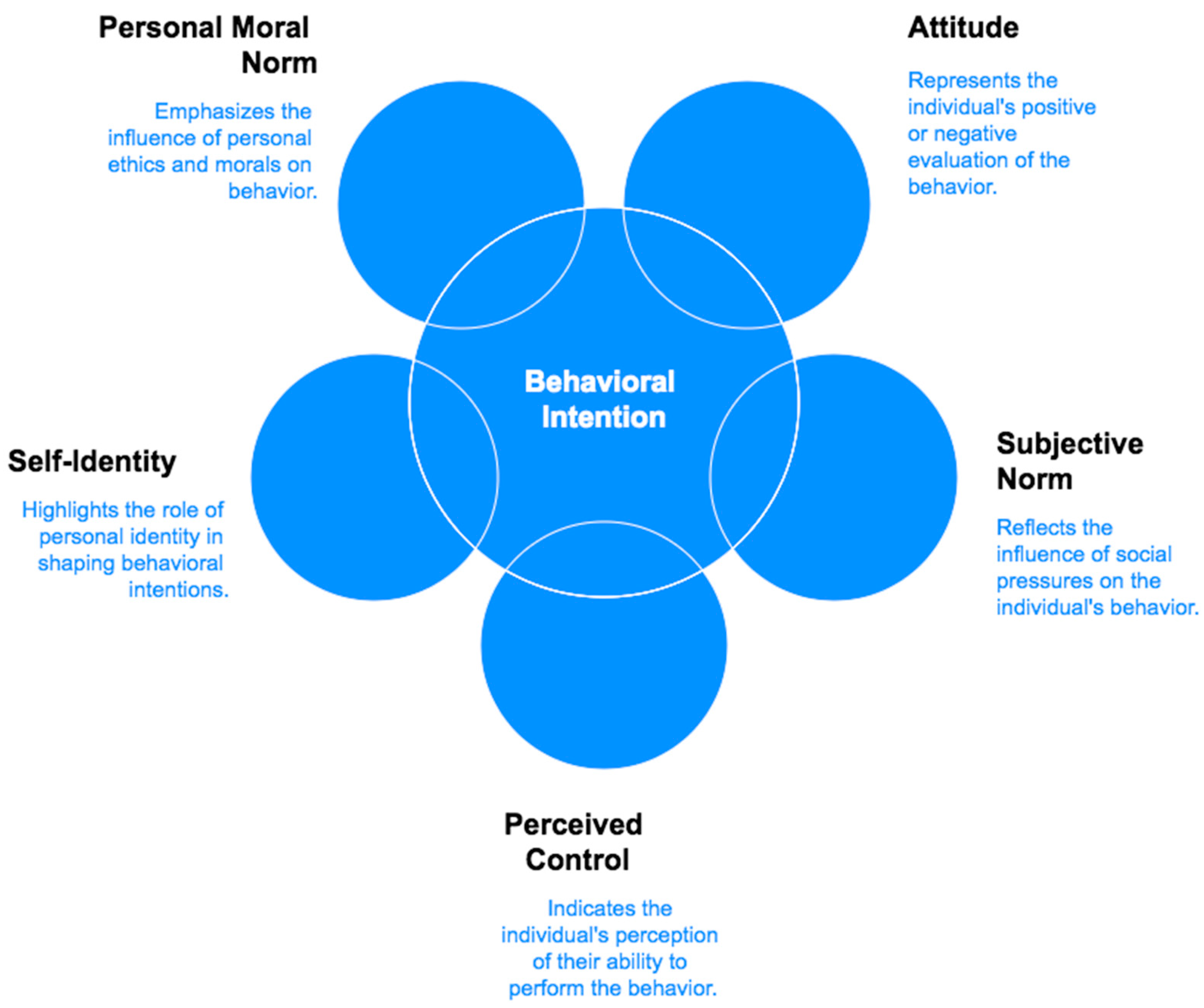

2.2. Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior

3. Conceptual Framework and Hypotheses

3.1. Attitude Toward Blockchain Adoption

3.2. Subjective Norm

3.3. Perceived Behavioral Control

3.4. Self-Identity

3.5. Personal Moral Norm

3.6. Behavioral Intention

4. Methodology

4.1. Research Instrument

4.2. Sample and Data Collection

5. Results

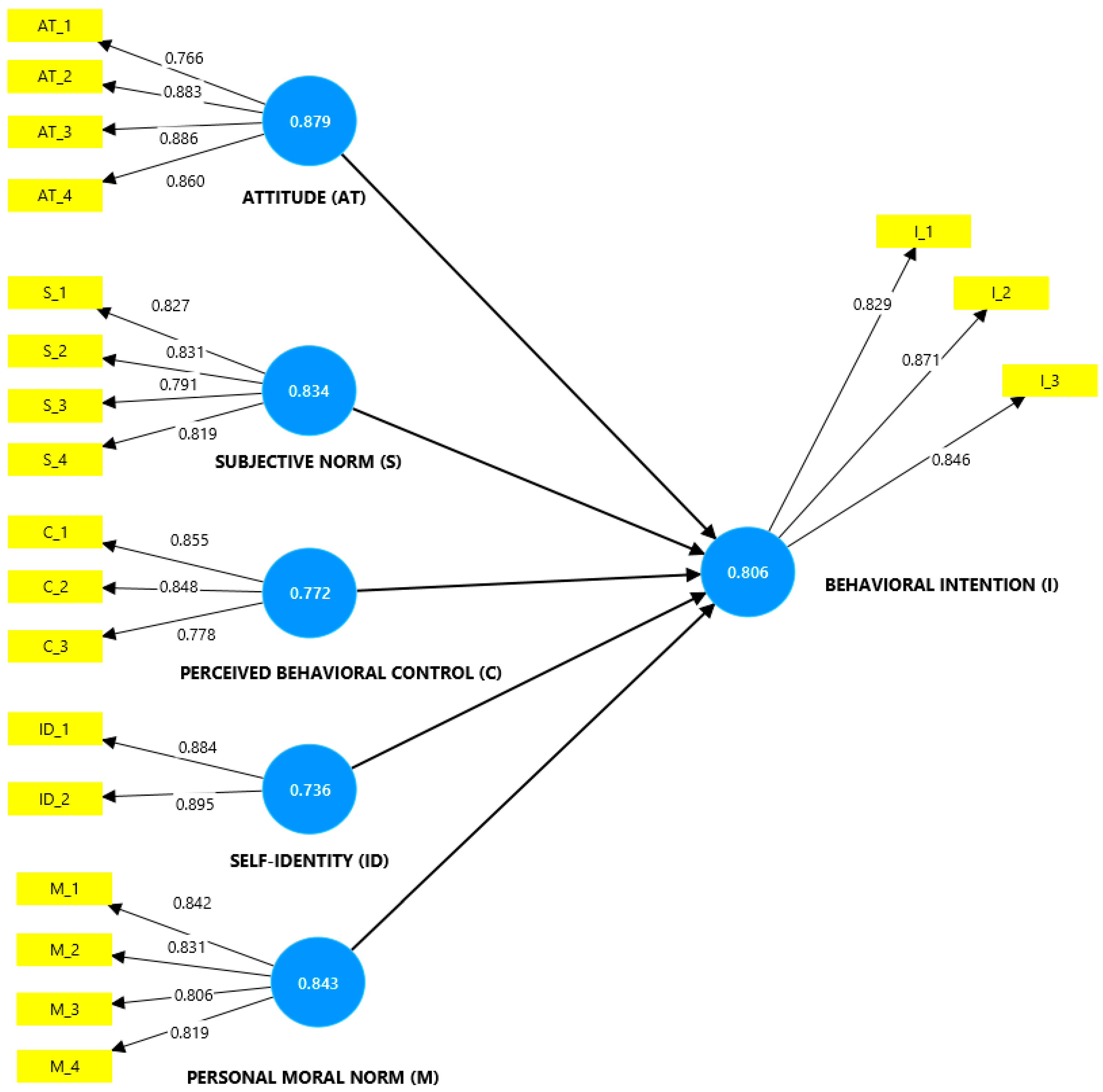

5.1. Measurement Model

5.2. Structural Model

6. Discussion

6.1. Managerial Implications

6.2. Theoretical Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AT | Attitude |

| BI | Behavioral Intention |

| PBC | Perceived Behavioral Control |

| SN | Subjective Norm |

| SI | Self-Identity |

| PMN | Personal Moral Norm |

| TPB | Theory of Planned Behavior |

| SEM | Structural Equation Modeling |

| PLS | Partial Least Squares |

| AVE | Average Variance Extracted |

| CR | Composite Reliability |

| HTMT | Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio |

| GDPR | General Data Protection Regulation |

Appendix A

| Constructs | Variable | Measurement Items | References |

| Attitude (AT) | AT1 | I think using blockchain-based systems for accounting and auditing services in my company is useful. | (Ajzen, 2002; Taylor & Todd, 1995; Bhattacherjee, 2000) |

| AT2 | I think using blockchain-based systems for accounting and auditing services in my company is significant. | ||

| AT3 | I think using blockchain-based systems for accounting and auditing services in my company is valuable. | ||

| AT4 | I think using blockchain-based systems for accounting and auditing services in my company is a wise action. | ||

| Subjective Norm (S) | S1 | My colleagues think that I should use a blockchain-based system for accounting and auditing services in my company. | (Ajzen, 2002; Taylor & Todd, 1995; Bhattacherjee, 2000; M.-F. Chen et al., 2009; Manning, 2009; Wang et al., 2014) |

| S2 | My managers think that I should use blockchain-based systems for accounting and auditing services in my company. | ||

| S3 | The high-level management team would want me to use blockchain-based systems for accounting and auditing services in my company. | ||

| S4 | Others who are important to me think I should use blockchain-based systems for accounting and auditing services in my company. | ||

| Perceived Behavioral Control (C) | C1 | I think that I am capable of using blockchain-based systems for accounting and auditing services in my company. | (Ajzen, 2002; Taylor & Todd, 1995; Hinds & Sparks, 2008; Fielding et al., 2008; Kaiser & Scheuthle, 2003) |

| C2 | I have the knowledge and skills to use blockchain-based systems for accounting and auditing services in my company. | ||

| C3 | Whether or not using blockchain-based systems for accounting and auditing services is completely up to me. | ||

| Behavioral Intention (I) | I1 | I am willing to use blockchain-based systems for accounting and auditing services in my company. | (Ajzen, 2012; Taylor & Todd, 1995; Bhattacherjee, 2000; Yadav & Pathak, 2016) |

| I1 | I intend to engage in blockchain-based systems activities for accounting and auditing services in my company. | ||

| I3 | I will make an effort to use blockchain-based systems for accounting and auditing services in my company. | ||

| Self-Identity (ID) | ID1 | I think of myself as a user of blockchain-based systems for accounting and auditing services. | (Fielding et al., 2008; Whitmarsh & O’Neill, 2010; Yazdanpanah et al., 2015; Cook et al., 2002) |

| ID2 | Using blockchain-based systems for accounting and auditing services is an important part of who I am. | ||

| Personal Moral Norm (M) | M1 | I think I have a moral responsibility to use blockchain-based systems for accounting and auditing services in my company. | (Bamberg et al., 2007; Kaiser and Scheuthle, 2003; Fornara et al., 2016) |

| M2 | Using blockchain-based systems for accounting and auditing services in my company depends on my own moral obligation. | ||

| M3 | I would feel unhappy if I do not use blockchain-based systems for accounting and auditing services in my company. | ||

| M4 | Not using blockchain-based systems for accounting and auditing services in my company would violate my moral principles. |

References

- Abdennadher, S., Grassa, R., Abdulla, H., & Alfalasi, A. (2021). The effects of blockchain technology on the accounting and assurance profession in the UAE: An exploratory study. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting, 20(1), 53–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, S., Arshad, J., & Alsadi, M. (2022). Chain-net: An internet-inspired framework for interoperable blockchains. Distributed Ledger Technologies: Research and Practice, 1(2), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (2002). Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32(4), 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (2012). The theory of planned behavior. In P. A. M. Lange, A. W. Kruglanski, & E. T. Higgins (Eds.), Handbook of theories of social psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 438–459). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Akman, İ., & Turhan, Ç. (2022). Sector diversity among IT professionals in the timing of blockchain adoption: An attitudinal perspective. Engineering Economics, 33(5), 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alazab, M., Alhyari, S., Awajan, A., & Abdallah, A. (2020). Blockchain technology in supply chain management: An empirical study of the factors affecting user adoption/acceptance. Cluster Computing, 24(1), 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhwaldi, A., Alidarous, M., & Alharasis, E. (2024). Antecedents and outcomes of innovative blockchain usage in accounting and auditing profession: An extended UTAUT model. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 37(5), 1102–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sartawi, A., Hegazy, M., & Hegazy, K. (2022). Guest editorial: The COVID-19 pandemic: A catalyst for digital transformation. Managerial Auditing Journal, 37(7), 769–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsulami, F. T. (2024). Factors associated with the public’s intention to report adverse drug reactions to community pharmacists in the Makkah region of Saudi Arabia: An application of the theory of planned behavior. Patient Preference and Adherence, 18, 2495–2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anis, A. (2023). Blockchain in accounting and auditing: Unveiling challenges and unleashing opportunities for digital transformation in Egypt. Journal of Humanities and Applied Social Sciences, 5(4), 359–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S., Hunecke, M., & Blöbaum, A. (2007). Social context, personal norms and the use of public transportation: Two field studies. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 27(3), 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacherjee, A. (2000). Acceptance of e-commerce services: The case of electronic brokerages. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics—Part A: Systems and Humans, 30(4), 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhmann, K., Criado, J., & Rialp, A. (2024). Predicting consumer intention to adopt battery electric vehicles: Extending the theory of planned behavior. Sustainability, 16(3), 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J., Qiu, H., & Morrison, A. (2023). Self-Identity matters: An extended theory of planned behavior to decode tourists’ waste sorting intentions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(6), 5099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y., Ajjan, H., Hong, P., & Le, T. (2018). Using social media for competitive business outcomes. Journal of Advances in Management Research, 15(2), 211–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S., Chaudhuri, R., Vrontis, D., & V., A. (2023). Adoption of blockchain technology in organizations: From morality, ethics and sustainability perspectives. Journal of Information, Communication and Ethics in Society, 22(1), 38–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M., & Tung, P. (2009). The moderating effect of perceived lack of facilities on consumers’ recycling intentions. Environment and Behavior, 42(6), 824–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-F., Pan, C.-T., & Pan, M.-C. (2009). The joint moderating impact of moral intensity and moral judgment on consumer’s use intention of pirated software. Journal of Business Ethics, 90(3), 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M., & Chong, H. (2022). Understanding the determinants of blockchain adoption in the engineering-construction industry: Multi-stakeholders’ analyses. IEEE Access, 10, 108307–108319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clohessy, T., & Acton, T. (2019). Investigating the influence of organizational factors on blockchain adoption. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 119(7), 1457–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clohessy, T., Treiblmaier, H., Acton, T., & Rogers, N. (2020). Antecedents of blockchain adoption: An integrative framework. Strategic Change, 29(5), 501–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, M., & Armitage, C. (1998). Extending the theory of planned behavior: A review and avenues for further research. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 28(15), 1429–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, A. J., Kerr, G. N., & Moore, K. (2002). Attitudes and intentions towards purchasing GM food. Journal Of Economic Psychology, 23(5), 557–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J., & Vasarhelyi, M. (2017). Toward blockchain-based accounting and assurance. Journal of Information Systems, 31(3), 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danach, K., Hejase, H., Faroukh, A., Fayyad-Kazan, H., & Moukadem, I. (2024). Assessing the impact of blockchain technology on financial reporting and audit practices. Asian Business Research, 9(1), 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, M., Raats, M., & Shepherd, R. (2011). The role of Self-Identity, past behavior, and their interaction in predicting intention to purchase fresh and processed organic food. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 42(3), 669–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeilzadeh, P., & Mirzaei, T. (2019). The potential of blockchain technology for health information exchange: Experimental study from patients’ perspectives. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21(6), e14184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fahlevi, M., Moeljadi, Aisjah, S., & Djazuli, A. (2023). Corporate governance in the digital age: A comprehensive review of blockchain, AI, and Big Data impacts, opportunities, and challenges. E3S Web of Conferences, 448, 02056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Febryaningrum, A., & Aligarh, F. (2024). Factors influencing social commerce adoption: A TOE framework analysis. ICOBUSS, 4, 340–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferri, L., Spanò, R., Ginesti, G., & Theodosopoulos, G. (2020). Ascertaining auditors’ intentions to use blockchain technology: Evidence from the Big 4 accountancy firms in Italy. Meditari Accountancy Research, 29(5), 1063–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding, K. S., McDonald, R., & Louis, W. R. (2008). Theory of planned behaviour, identity and intentions to engage in environmental activism. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 28(4), 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fomin, V., Gürpinar, T., & Balevičienė, D. (2024). Design of a blockchain technology competence model for interdisciplinary curricula development. Information & Media, 99, 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornara, F., Pattitoni, P., Mura, M., & Strazzera, E. (2016). Predicting intention to improve household energy efficiency: The role of value–belief–norm theory, normative and informational influence, and specific attitude. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 45, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, M., & Brender, N. (2021). How do the current auditing standards fit the emergent use of blockchain? Managerial Auditing Journal, 36(3), 365–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurtu, A., & Johny, J. (2019). Potential of blockchain technology in supply chain management: A literature review. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 49(9), 881–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hannah, S., Thompson, R., & Herbst, K. (2018). Moral identity complexity: Situated morality within and across work and social roles. Journal of Management, 46(5), 726–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardjono, T., Lipton, A., & Pentland, A. (2020). Toward an interoperability architecture for blockchain autonomous systems. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 67(4), 1298–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haryanto, S., & Sudaryati, E. (2020). The ethical perspective of millennial accountants in responding to opportunities and challenges of blockchain 4.0. Journal of Accounting and Investment, 21(3), 452–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, A., Sikarwar, P., Mishra, A., Raghuwanshi, S., Singhal, A., Joshi, A., Singh, P. R., & Dixit, A. (2024). Determinants of Behavioral Intention to use digital payment among Indian youngsters. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(2), 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasani, T., Bojei, J., & Dehghantanha, A. (2017). Investigating the antecedents to the adoption of SCRM technologies by start-up companies. Telematics and Informatics, 34(5), 655–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2014). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinds, J., & Sparks, P. (2008). Engaging with the natural environment: The role of affective connection and identity. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 28(2), 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, M., & White, K. (2009). To be a donor or not to be? Applying an extended theory of planned behavior to predict posthumous organ donation intentions. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 39(4), 880–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C., Smith, A., & Conner, M. (2003). Applying an extended version of the theory of planned behaviour to physical activity. Journal of Sports Sciences, 21(2), 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jassem, S., Sayari, K., & Abdelfattah, F. (2024). Blockchain’s transformative role in the financial sector (pp. 297–326). IGI Global Scientific Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasuriya, D., & Sims, A. (2022). From the abacus to enterprise resource planning: Is blockchain the next big accounting tool? Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 36(1), 24–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F. G., & Scheuthle, H. (2003). Two challenges to a moral extension of the theory of planned behavior: Moral norms and just world beliefs in conservationism. Personality and Individual Differences, 35(5), 1033–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kend, M., & Nguyen, L. (2020). Big data analytics and other emerging technologies: The impact on the Australian audit and assurance profession. Australian Accounting Review, 30(4), 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N., & Hadaya, P. (2018). Minimum sample size estimation in PLS-SEM: The inverse square root and gamma-exponential methods. Information Systems Journal, 28(1), 227–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koster, F., & Borgman, H. (2020, January 7–10). New kid on the block! Understanding blockchain adoption in the public sector. 53rd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Maui, HI, USA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J., Rani, G., Rani, M., & Rani, V. (2024). Blockchain technology adoption and its impact on SME performance: Insights for entrepreneurs and policymakers. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy, 18(5), 1147–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R., Kumar, K., Singh, R., Sá, J. C., Carvalho, S., & Santos, G. (2023). Modeling environmentally conscious purchase behavior: Examining the role of ethical obligation and green Self-Identity. Sustainability, 15(8), 6426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, R., Villiers, C., Moscariello, N., & Pizzo, M. (2021). The disruption of blockchain in auditing—A systematic literature review and an agenda for future research. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 35(7), 1534–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, M. (2009). The effects of subjective norms on behaviour in the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analysis. British Journal of Social Psychology, 48(4), 649–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mthimkhulu, A., & Jokonya, O. (2022). Exploring the factors affecting the adoption of blockchain technology in the supply chain and logistic industry. Journal of Transport and Supply Chain Management, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, P., & Abeygunasekera, A. (2022). Blockchain adoption in accounting and auditing: A qualitative inquiry in Sri Lanka. Colombo Business Journal: International Journal of Theory and Practice, 13(1), 57–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, E., & Boulianne, E. (2020). Blockchain in accounting research and practice: Current trends and future opportunities. Accounting Perspectives, 19(4), 325–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priom, M., Mudra, S., Ghose, P., Islam, K., & Hasan, M. (2024). Blockchain applications in accounting and auditing: Research trends and future research implications. International Journal of Economics, Business and Management Research, 8(7), 225–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C. M., Silva, D., & Bido, D. (2014). Structural equation modeling with the SmartPLS. Brazilian Journal of Marketing – Revista Brasileira de Marketing, 13(2), 56–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rise, J., Sheeran, P., & Hukkelberg, S. (2010). The role of Self-Identity in the theory of planned behavior: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 40(5), 1085–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronaghi, M., & Mosakhani, M. (2021). The effects of blockchain technology adoption on business ethics and social sustainability: Evidence from the Middle East. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 24(5), 6834–6859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiq, A., Javed, M., Khalid, R., Almogren, A., Shafiq, M., & Javaid, N. (2021). Blockchain based data and energy trading in internet of electric vehicles. IEEE Access, 9, 7000–7020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santhosh, N., & Pavan Kumar Raju, R. (2025). Adoption of blockchain technology in accounting practices—A practitioner’s perspective. International Journal for Multidisciplinary Research, 7(1), 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, J., & Leoni, G. (2019). Accounting and auditing at the time of blockchain technology: A research agenda. Australian Accounting Review, 29(2), 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shbail, M., Bani-Khalid, T., Ananzeh, H., Al-Hazaima, H., & Shbail, A. (2023). Technostress impact on the intention to adopt blockchain technology in auditing companies [Special issue]. Journal of Governance and Regulation, 12(3), 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, M. (2019). A primer for information technology general control considerations on a private and permissioned blockchain audit. Current Issues in Auditing, 13(1), A15–A29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, M. (2021). Preparing auditors for the blockchain oracle problem. Current Issues in Auditing, 15(2), P27–P39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, Y., & Fang, K. (2004). The use of a decomposed theory of planned behavior to study internet banking in Taiwan. Internet Research, 14(3), 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões, M., Cavalcanti, J., Melo, J., & Reis, C. (2021). Benefits of using blockchain technology as an accounting auditing instrument. Revista Ambiente Contábil, 13(1), 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B., & Low, K. (2019). Blockchain as the database engine in the accounting system. Australian Accounting Review, 29(2), 312–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S., & Todd, P. (1995). Decomposition and crossover effects in the theory of planned behavior: A study of consumer adoption intentions. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 12(2), 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tezel, A., Papadonikolaki, E., Yitmen, İ., & Hilletofth, P. (2020). Preparing construction supply chains for blockchain technology: An investigation of its potential and future directions. Frontiers of Engineering Management, 7(4), 547–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiron-Tudor, A., Deliu, D., Farcane, N., & Dontu, A. (2021). Managing change with and through blockchain in accountancy organizations: A systematic literature review. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 34(2), 477–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuruta, M. (2024). Interaction between sovereign quanto credit default swap spreads and currency options. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(2), 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V., & Davis, F. (2000). A theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model: Four longitudinal field studies. Management Science, 46(2), 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, N., & Barkhi, R. (2020). Evaluating blockchain using coso. Current Issues in Auditing, 15(1), A57–A71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C., Zhang, J., & Yu, P. (2014). The impact of subjective norm on behavioral intention of mobile banking adoption: The moderating role of user experience. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 42(10), 1413–1420. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, M., & Ding, R. (2018, December 2–3). Research on financial audit innovation based on blockchain technology. 2017 International Seminar on Social Science and Humanities Research (SSHR 2017), Bangkok, Thailand. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- White, K., & Hyde, M. (2011). The role of self-perceptions in the prediction of household recycling behavior in Australia. Environment and Behavior, 44(6), 785–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmarsh, L., & O’Neill, S. (2010). Green identity, green living? The role of pro-environmental self-identity in determining consistency across diverse pro-environmental behaviours. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 30(3), 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibowo, T., & Christian, Y. (2021). Usage of blockchain to ensure audit data integrity. EQUITY, 24(1), 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R., & Pathak, G. S. (2016). Young consumers’ intention towards buying green products in a developing nation: Extending the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Cleaner Production, 135, 732–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdanpanah, M., Forouzani, M., Abdeshahi, A., & Jafari, A. (2015). Investigating the effect of moral norm and Self-Identity on the intention toward water conservation among Iranian young adults. Water Policy, 18(1), 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| References | Research Focus | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Perera and Abeygunasekera (2022) | The researchers performed a qualitative study on blockchain adoption in Sri Lanka’s accounting and auditing sectors, highlighting the need for studies that incorporate Self-Identity and moral norms to capture nuanced professional decision-making. | This points to a gap in applying TPB to these specialized fields. |

| Jayasuriya and Sims (2022) | The researchers contrasted industry and academic views on blockchain integration into accounting systems, proposing frameworks to consolidate fragmented research. | They emphasized the need for extended TPB constructs to better understand Behavioral Intentions in professional contexts. |

| Priom et al. (2024) | Bibliometric analysis, revealing that while blockchain’s benefits are recognized, comprehensive studies incorporating identity and ethical factors into adoption models are lacking. | This supports extending TPB to address unique behavioral influences in these domains. |

| Jackson et al. (2003) | The researchers demonstrated that including Self-Identity and moral norms enhances TPB’s predictive power in physical activity studies. | Their methodological approach suggests that similar extensions could provide deeper insights into blockchain adoption in accounting and auditing. |

| Construct | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Attitude | 3.97 | 0.82 |

| Subjective Norm | 3.84 | 0.87 |

| Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC) | 3.72 | 0.90 |

| Self-Identity | 3.65 | 0.85 |

| Personal Moral Norm | 4.05 | 0.78 |

| Behavioral Intention | 3.89 | 0.83 |

| Demographic characteristics | f | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 349 | 46.5% |

| Male | 402 | 53.5% |

| Education | ||

| High School | 52 | 6.9% |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 391 | 52.1% |

| Master’s Degree | 250 | 33.3% |

| PhD | 58 | 7.7% |

| Age | ||

| 20–30 years | 73 | 9.7% |

| 31–40 years | 287 | 38.2% |

| 41–50 years | 212 | 28.2% |

| 51+ years | 179 | 23.8% |

| Income | ||

| <EUR 25,000 | 373 | 49.7% |

| EUR 25,001–40,000 | 129 | 17.2% |

| EUR 40,001–55,000 | 205 | 27.3% |

| >EUR 55,001 | 44 | 5.9% |

| Origin | ||

| East Europe | 321 | 42.7% |

| North Europe | 200 | 26.6% |

| South Europe | 155 | 20.6% |

| West Europe | 75 | 10.0% |

| Question = I possess a comprehensive understanding of blockchain technology and its applications in accounting and auditing services. | ||

| YES | 751 | 100 |

| Total | 751 | 100 |

| Construct | Item | Standardized Loading > 0.704 | Cronbach’s Alpha > 0.7 | Composite Reliability CR > 0.7 | Average Variance Extracted AVE > 0.5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATTITUDE (AT) | AT_1 | 0.766 | 0.879 | 0.912 | 0.723 |

| AT_2 | 0.883 | ||||

| AT_3 | 0.886 | ||||

| AT_4 | 0.860 | ||||

| BEHAVIORAL INTENTION (I) | I_1 | 0.829 | 0.806 | 0.885 | 0.720 |

| I_2 | 0.871 | ||||

| I_3 | 0.846 | ||||

| PERCEIVED BEHAVIORAL CONTROL (C) | C_1 | 0.855 | 0.772 | 0.867 | 0.685 |

| C_2 | 0.848 | ||||

| C_3 | 0.778 | ||||

| PERSONAL MORAL NORM (M) | M_1 | 0.842 | 0.843 | 0.895 | 0.680 |

| M_2 | 0.831 | ||||

| M_3 | 0.806 | ||||

| M_4 | 0.819 | ||||

| SELF-IDENTITY (ID) | ID_1 | 0.884 | 0.736 | 0.883 | 0.791 |

| ID_2 | 0.895 | ||||

| SUBJECTIVE NORM (S) | S_1 | 0.827 | 0.836 | 0.889 | 0.668 |

| S_2 | 0.831 | ||||

| S_3 | 0.791 | ||||

| S_4 | 0.819 |

| ATTITUDE (AT) | BEHAVIORAL INTENTION (I) | PERCEIVED BEHAVIORAL CONTROL (C) | PERSONAL MORAL NORM (M) | SELF-IDENTITY (ID) | SUBJECTIVE NORM (S) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATTITUDE (AT) | 0.850 | |||||

| BEHAVIORAL INTENTION (I) | 0.073 | 0.849 | ||||

| PERCEIVED BEHAVIORAL CONTROL (C) | 0.033 | 0.529 | 0.828 | |||

| PERSONAL MORAL NORM (M) | 0.02 | 0.567 | 0.591 | 0.825 | ||

| SELF-IDENTITY (ID) | −0.025 | 0.441 | 0.463 | 0.468 | 0.890 | |

| SUBJECTIVE NORM (S) | −0.022 | 0.532 | 0.565 | 0.589 | 0.457 | 0.817 |

| ATTITUDE (AT) | BEHAVIORAL INTENTION (I) | PERCEIVED BEHAVIORAL CONTROL (C) | PERSONAL MORAL NORM (M) | SELF-IDENTITY (ID) | SUBJECTIVE NORM (S) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATTITUDE (AT) | ||||||

| BEHAVIORAL INTENTION (I) | 0.094 | |||||

| PERCEIVED BEHAVIORAL CONTROL (C) | 0.074 | 0.659 | ||||

| PERSONAL MORAL NORM (M) | 0.038 | 0.681 | 0.731 | |||

| SELF-IDENTITY (ID) | 0.06 | 0.568 | 0.621 | 0.595 | ||

| SUBJECTIVE NORM (S) | 0.063 | 0.644 | 0.705 | 0.701 | 0.583 |

| Hypotheses | Std. Beta (β) | Std. Error | T Values | p Values | Conclusions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | ATTITUDE (AT) -> BEHAVIORAL INTENTION (I) | 0.069 | 0.033 | 2.12 | 0.034 | Supported |

| H2 | SUBJECTIVE NORM (S) -> BEHAVIORAL INTENTION (I) | 0.207 | 0.038 | 5.523 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H3 | PERCEIVED BEHAVIORAL CONTROL (C) -> BEHAVIORAL INTENTION (I) | 0.189 | 0.045 | 4.187 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H4 | SELF-IDENTITY (ID) -> BEHAVIORAL INTENTION (I) | 0.134 | 0.030 | 4.454 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H5 | PERSONAL MORAL NORM (M) -> BEHAVIORAL INTENTION (I) | 0.269 | 0.046 | 5.832 | 0.000 | Supported |

| Latent Variables | R2 | Adj. R2 | Q2 | F2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BEHAVIORAL INTENTION (I) | 0.427 | 0.423 | 0.417 | |

| ATTITUDE (AT) -> BEHAVIORAL INTENTION (I) | 0.011 | 1.195 | 0.008 | |

| PERCEIVED BEHAVIORAL CONTROL (C) -> BEHAVIORAL INTENTION (I) | 0.037 | 1.969 | 0.035 | |

| PERSONAL MORAL NORM (M) -> BEHAVIORAL INTENTION (I) | 0.070 | 3.105 | 0.068 | |

| SELF-IDENTITY (ID) -> BEHAVIORAL INTENTION (I) | 0.023 | 2.139 | 0.022 | |

| SUBJECTIVE NORM (S) -> BEHAVIORAL INTENTION (I) | 0.043 | 2.77 | 0.042 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gkekas, N.; Ireiotis, N.; Kounadeas, T. Drivers of Blockchain Adoption in Accounting and Auditing Services: Leveraging Theory of Planned Behavior with Identity and Moral Norms. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 573. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18100573

Gkekas N, Ireiotis N, Kounadeas T. Drivers of Blockchain Adoption in Accounting and Auditing Services: Leveraging Theory of Planned Behavior with Identity and Moral Norms. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(10):573. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18100573

Chicago/Turabian StyleGkekas, Nikolaos, Nikolaos Ireiotis, and Theodoros Kounadeas. 2025. "Drivers of Blockchain Adoption in Accounting and Auditing Services: Leveraging Theory of Planned Behavior with Identity and Moral Norms" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 10: 573. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18100573

APA StyleGkekas, N., Ireiotis, N., & Kounadeas, T. (2025). Drivers of Blockchain Adoption in Accounting and Auditing Services: Leveraging Theory of Planned Behavior with Identity and Moral Norms. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(10), 573. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18100573