Abstract

This study aims to investigate the impact of digital transformation on corporate tax avoidance. In fact, this revolution has pervasively affected firms in different aspects and represents a significant opportunity to modernize their internal processes, bringing alongside a set of challenges that they must overcome. One hypothesis posits that digitalization enhances information transparency and internal control, reducing tax avoidance, while the other one suggests that the increase in digitalization leads to more complex and opaque transactions, leaving avenues for more aggressive tax strategies. This paper uses data of listed firms in the Casablanca Stock Exchange from 2020 to 2024, excluding the financial sector due to its specific tax regulation, leaving a final sample of 56 companies and 272 firm-year observations. It applies an OLS regression to assess the relation between the two variables, controlling for a set of firm and governance characteristics. The aim of the article is to address the scholarly debate by providing insights into an emerging economy where there is little research on the subject. The findings reveal that digital transformation contributes to the decrease in corporate tax avoidance in conjunction with governance variables like the presence of independent directors on the board and the duality of a CEO position, strongly supporting the first hypothesis. Notably, the OLS regression results show that an increase in digitalization by 1 point is associated with a decrease of 40.4755 in the book-tax differences, significant at the 5% level. The results provide high support for firms to invest in technologies in order to optimize their internal processes and improve their data quality; it also calls for tax authorities to strengthen their digital audit capacities and integrate data-driven tools to detect and interpret signals of potential tax-aggressive strategies.

1. Introduction

The rapid expansion of the digital economy has created challenges for firms, compelling them to rethink their processes in a context of fierce competition, rapid technological development, and significant financial constraints. Examining its impact on corporate tax avoidance is paramount due to the strain on modern economies’ budgets in the aftermath of recent crises and the need to balance major investments and debt obligations (OECD, 2020).

The scholarly discourse on the subject is characterized by a significant dichotomy. Divergence emerges between authors, with some outlining the benefits in terms of financial data transparency and optimizing firms’ internal control systems, in addition to reducing the asymmetry of information between the stakeholders (Zhang & She, 2024; T. Guo et al., 2023; Xie & Huang, 2023). On the other hand, scholars are warning of the potential risks that could erode the tax base and deprive states of important tax resources, especially because digitalization promotes intangible transactions that are harder to control by authorities, in addition to the high cost of implementing such technologies.

In Morocco, the issue is highly relevant. The country faces a persistent tax gap estimated at 6.7% of GDP (Doghmi, 2020), which pressures the authorities to broaden the tax base and strengthen revenue mobilization to support investments in infrastructure and social services. Addressing tax avoidance and fraud is one of the main tools to mitigate this tax gap, mainly through the use of strong digital capacities by the tax administration, with cutting-edge technologies at the base of such a strategy. The country has already launched ambitious reforms, including the Digital Morocco 2030 strategy and the 2024–2028 plan of the Directorate General of Taxes (DGI), which aim to strengthen compliance through predictive tax controls, user-oriented digital platforms, and data-driven audits. However, despite these reforms, empirical evidence on the effect of digitalization on tax behavior in Morocco—and more broadly in the MENA region—remains scarce. This gap provides an opportunity for our study to contribute to the literature by highlighting the interaction between corporate digitalization, tax avoidance, and governance mechanisms.

Using data from 56 non-financial companies listed on the Casablanca Stock Exchange over 2020–2024, this paper tests two competing hypotheses: first, that digital transformation enhances internal controls and information transparency, thereby reducing tax avoidance; second, that digitalization may instead facilitate more complex transactions and allow more aggressive tax-planning. Our results support the first hypothesis: an increase in digitalization by one unit is associated with a statistically significant reduction in the book-tax differences of approximately 40.48, significant at the 5% level.

The evidence also indicates that governance characteristics—such as the presence of independent directors and the separation of the CEO and board chair—strengthen this negative relationship. These findings enrich the debate by offering novel insights from an emerging market, clarifying how digital transformation interacts with firm governance to influence tax avoidance. Moreover, by detailing Morocco’s institutional features and regulatory context, we highlight the extent to which our results may be generalized to similar economies while acknowledging country-specific constraints that may limit broader applicability.

In the MENA context, existing studies have predominantly focused on determinants of tax avoidance such as financial performance (Kateb et al., 2025), corporate governance (Alshabibi et al., 2022), institutional quality (Eldomiaty et al., 2023), and corporate social responsibility (Almutairi & Abdelazim, 2025). However, despite the growing importance of digitalization in reshaping financial practices, digital transformation has not been recognized as a determinant of tax avoidance. This gap underscores the need to explore how technological advancements may influence tax behavior in the Moroccan listed firms.

This paper examines whether digitalization affects the tax avoidance level by providing insights in the context of an emerging economy. It contributes to the debate on the impact of new technologies on firms’ tax strategies, particularly in the Moroccan context, where literature related to this specific subject is scarce. The results indicate that digital transformation reduces tax avoidance, as measured by the book-tax differences, confirming the hypothesis that sees digitalization as a disciplining mechanism. This mechanism not only benefits society by curbing tax evasion but also fosters business performance by improving internal systems and optimizing information dissemination among all firm stakeholders.

The paper contributes to the literature in three ways. First, it provides empirical evidence that digitalization reduces corporate tax avoidance, supporting the hypothesis that digital transformation acts not only as a disciplining mechanism but also as a tool to enhance business performance and optimize information dissemination among stakeholders. Second, it offers a nuanced and granular perspective of this interaction by integrating corporate governance mechanisms—specifically board independence and CEO duality—and demonstrating how they reinforce or weaken the relationship. Third, it delivers actionable insights for policymakers and tax authorities, highlighting the benefits of digital transformation in enhancing data transparency and compliance, curbing tax aggressiveness, and modernizing tax systems.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: The Section 2 sets the theoretical and conceptual foundation of the study by reviewing the literature on digital transformation and corporate tax avoidance. The Section 3 details the research methodology, sample selection, and model designs. The Section 4 presents and discusses the results. Finally, the Section 5 concludes with the theoretical and practical implications, in addition to limitations and avenues for future research.

2. Theoretical Foundation and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Conceptual Framework

2.1.1. Digital Transformation

Digital transformation is a comprehensive phenomenon reshaping firms’ strategies and leading to a reengineering of their systems and processes in response to an ever-evolving environment (Vial, 2019). It encompasses the leveraging of new technologies like artificial intelligence, enterprise resource planning (ERP), and big data to harness efficiency in costs and time and enhance customer experience, pushing companies to rethink their strategies and business models (Piccinini et al., 2015; Hess et al., 2016). However, its effect on tax avoidance strategies remains contested.

Verhoef et al. (2021) consider digital transformation as the final stage of a three-phase model where companies start by digitizing their data by converting them from paper analog to digital format, followed by the implementation of technologies in their internal processes seeking to save costs and improve overall efficiency, with digital transformation being the pinnacle consisting of an overhaul across the firm and leading to the development of new business models and a shift in its culture, governance, and strategy. The authors outline that companies must support this evolution with strong digital resources in line with their needs and reorganize their hierarchical structure by being more flexible and agile, in addition to adopting clear digital strategies and KPIs to measure the relevance of their investment.

Building on the resource-based view, Elia et al. (2021) argue that firms must not only possess the digital resources consisting of infrastructure and software but they also must develop and build digital capabilities by leveraging their human capital competency and skills in order to keep in line with the advancement of technologies.

However, authors like X. Guo et al. (2023) argue that digitalization is not always a remedy for all the hurdles that companies face; they propose the concept of “digitalization paradox” when substantial investments are made for upgrading technological capacities without significant benefits on financial performance due to the high cost of digital assets and management expenses related to the hiring of highly skilled experts.

This revolution also brings challenges like opening avenues for tax avoidance via the concealment of digital transactions, which are harder to track by tax authorities (Chen et al., 2025).

Despite these insights, the literature shows substantial limitations. First, most studies examining the effect of digitalization on tax avoidance overlook the complexity of the phenomenon and its interaction with other mechanisms such as governance and institutional contexts. Integrating these dimensions is crucial to capture nuances regarding the interaction between the two concepts. Second, the proxies used to measure digitalization, such as keyword frequency or R&D investments, are subject to managerial manipulation and may overlook the depth of the transformation.

2.1.2. Tax Avoidance

Tax avoidance, or tax aggressiveness, refers to strategies that seek to minimize the tax liability of firms and taxpayers by exploiting loopholes in the tax code and legal arbitrages; it employs legal mechanisms as opposed to tax evasion (Alm, 2021).

It skews the tax structure of countries, depriving them of revenues that could be redirected to infrastructure investments. This also impacts the feeling of equity of individuals who feel that they are not treated equally as their peers who fall into the same category of revenues (Braithwaite, 2003).

Stiglitz (1985) defines tax avoidance as sophisticated strategies to optimize the tax charge; he cites three main categories of strategies: the postponement of taxes, tax arbitrage across individuals, and tax arbitrage across income streams.

In their seminal article, Allingham and Sandmo (1972) construct a model where the taxpayer makes a gamble between evasion and compliance; this arbitrage is based on the probability of detection and the incurred fine. Slemrod and Yitzhaki (2000) extend the model to incorporate tax avoidance, framing it as legal but also involving compliance costs incurred by taxpayers for setting up the strategies and paying consultants. In addition to costs for governments related to the enforcement of the tax rules, it also has efficiency costs by distorting taxpayers from optimal resource allocation.

Desai and Dharmapala (2006) focused on tax evasion on a corporate level; they argue that to curb the rent-seeking behavior of managers, incentives like equity-based compensation and strong governance structure are to be implemented.

Another question mainly asked by researchers is the reason pushing most firms not to engage in such aggressive tax behavior, some of them hypothesizing that the reputational cost is the main driver because of the costs that may damage their relationship with stakeholders ranging from customers to tax authorities; the empirical tests remain inconclusive (Gallemore et al., 2014).

Recent research confirms that digital transformation plays a significant role in enhancing transparency and reducing tax avoidance practices in the banking sector. For instance, Souguir et al. (2025) highlight how digitalization reshapes tax policy by limiting opportunities for avoidance and strengthening accountability mechanisms.

New issues like the impact of technology on tax avoidance have arisen; while it can help to enforce compliance by leaving an audit trail with tools like electronic invoicing, particularly with the value-added tax (Heinemann & Stiller, 2024), it also facilitates the hiding of transactions and engagement in more global tax planning schemes by exploiting the gig economy, making it critical for tax authorities to strengthen the reporting obligation and develop their traditional methods of enforcement (Enofe et al., 2019).

These studies reveal a clear evolution in the literature on tax avoidance. The focus has evolved from the individual taxpayer’s decision, based on a rational calculation of risk and rewards (Allingham & Sandmo, 1972), to a focus on corporate drivers to engage in such tax behavior, such as managerial incentives (Desai & Dharmapala, 2006), and pressure from external stakeholders (Gallemore et al., 2014). This body of research frames firms tax strategy as a cost–benefit aimed at lowering their tax liability. While this traditional analysis explains some parts of the phenomenon, it clearly overlooks new drivers that emerged in the age of the digital economy.

While prior studies on tax avoidance have provided substantial contributions, they present some limitations. First, they mostly focus on developed countries like the United States. The findings from the studies may not be generalizable to different contexts, especially emerging economies like Morocco, which gives novelty to and motivates our study. Second, recent studies overlook the transformative nature of digitalization on all of the companies’ processes, including its own governance structure and strategies.

2.2. Theoretical Framework

2.2.1. Agency Theory

Proposed by Jensen and Meckling (1979), the theory studies the relationship between a principal and his agent; this relation is characterized by the asymmetry of information and opportunistic behavior. The managers engage in aggressive tax strategies to maximize the after-tax profits in order to increase their own revenue.

The relationship between shareholders and managers is ultimately based on the confidence that each party has in the other. Given that, by essence, managers do not own the assets under their stewardship, their interests generally do not align with those of the owners. Problems like suboptimal decision-making, ethical issues, and rent extraction can occur due to the decrease in corporate transparency. In order to mitigate these problems, firms set strong corporate governance structures and encourage regular reporting of data and frequent audits to ascertain that the company’s assets are employed to their fullest potential, guaranteeing optimal performance.

Drawing on agency theory (Jensen & Meckling, 1979), the adoption of advanced technological strategies enables firms to strengthen information transparency, improve internal control and governance mechanisms (T. Guo et al., 2023), and ultimately lower agency costs.

The use of technologies enhance transparency and more easily facilitates the flow of financial information in the company. As a result, the asymmetry of information between the managers and the shareholders on one hand and with the tax authority on the other hand diminishes and makes the relationship more trustful. It also makes the monitoring of compliance by the tax administration easier thanks to tools like big data, artificial intelligence, and machine learning, making it simpler to track any discrepancy in data and avoid any non-ethical fiscal behavior.

From an alternative perspective, and in line with agency theory (Jensen & Meckling, 1979), digital transformation can act as a deterrent to tax avoidance. By strengthening internal controls and enhancing financial transparency, digital technologies help mitigate conflicts of interest between managers and shareholders (Zhai et al., 2022). Although shareholders are often focused on profit maximization, the greater visibility and scrutiny brought about by digitalization reshape the risk–return trade-off associated with aggressive tax planning, thereby discouraging such practices.

Digitalization also makes oversight by shareholders easier thanks to the real-time reporting of financial data, making it simpler to keep track of managerial opportunism and save their interests. Thus, by digitizing its information systems and processes, the risks of data manipulation by management to distort the company’s real financial situation are reduced, and shareholders can assess the company’s real performance and implement real-time monitoring based on exhaustive, up-to-date data flow. Digitalization also makes communication smoother between the company and its stakeholders, making the relationship more trustful.

On the other hand, digitalization of companies complexifies their processes and could increase the opacity of information between managers and shareholders, which calls for an increase in internal control mechanisms and their evolution in congruence with the adoption of new technologies by the firms.

While the studies (T. Guo et al., 2023; Zhai et al., 2022) highlight the clear impact of digital transformation on reducing agency costs and improving data transparency, they mostly come from studying specific industries and contexts, limiting their generalizability. They also overlook contextual factors that could moderate the effect on agency issues, like regulatory environment, strength of tax administration enforcement capacities, firm size, or even organizational culture.

2.2.2. Signal Theory

In the context of information asymmetry, one party (managers), possessing more information than the other (tax authority, shareholders), sends signals in order to share private information that it possesses. The theory introduced by Ross (1977) is based on two founding principles: the same information is not known by all stakeholders, and even so, it is not interpreted in the same manner.

In the context of digitalization, decoding the signal may be complex and can lead to two opposing interpretations:

- (a)

- Digitalization as a strong governance mechanism

Firms that embrace digital transformation invest heavily in technologies that help to streamline their processes and improve the performance of their activities. By enhancing data quality and accuracy, the governance mechanism is strengthened and leaves avenues for external oversight by investors and tax authorities.

Digital transformation reduces information asymmetry, making it harder to conceal relevant transactions and any financial or tax decision that could significantly affect the company’s financial records.

The implementation of digital technologies like electronic filing leaves a digital footprint of all the company’s activities, enhancing the transparency of all the data it generates (Zhang & She, 2024). This strengthens tax authorities’ capacities to enforce tax compliance by leveraging all the data generated. In fact, the provision of relevant and high-quality data helps tax administration to fine-tune its algorithms to better comprehend the tax strategies of companies in detail and better target high-risk taxpayers, in addition to allowing the real-time monitoring of tax compliance.

Digitalization helps companies to integrate tax technologies to show their goodwill to tax authorities. For example, the implementation of electronic invoices and automatic exchange of information reduces the information asymmetry and can also help managers to monitor the firm’s tax risk in real time.

- (b)

- Digitalization as a tool for tax avoidance

By complexifying their activities and engaging in digital transactions like selling through intangible channels like e-commerce, firms make it harder for tax authorities to monitor their tax compliance. The very concept of permanent establishment on which traditional tax laws are grounded is eroded, complexifying the taxation of the activities that firms engage in.

Digitalization increases information asymmetry by amplifying the opacity of transactions that are infinitely bigger in volume. This complexifies oversight by shareholders and authorities and hampers the assessment of risks and relevance of the activities compared to the firm’s objectives and long-term strategy.

Given that the digital economy is still a nascent field and not all of its aspects are fully understood and taxed, companies find loopholes and legislative gaps that they exploit to maximize their profits. The increase in intangible transactions, as an example, hardens the monitoring of compliance by tax authorities whose resources are limited and not always in line with the sophistication of big firms’ tax systems.

The insights provided by the signaling theory are highly relevant; however, the literature clearly focuses on agency issues, often overlooking the effect of signals in facilitating or concealing tax avoidance behavior. They also neglect how these signals are interpreted by investors and tax authorities, which is crucial for understanding their effectiveness.

The agency theory emphasizes the disciplining effect of digitalization; this transformation contributes directly to the improvement of data traceability and transparency, reduces information asymmetry between managers and stakeholders, and limits any managerial discretion, which greatly curbs aggressive tax strategies.

On the other hand, signaling theory exposes digitalization as a signal and focuses on its interpretation. For example, firms may show that they engage in digital transformation to reinforce their financial transparency while engaging in complex and opaque tax-avoidance strategies, which hardens the enforcement by tax authorities and weakens their collection capacity.

2.3. Hypothesis Development

The empirical literature that studies the relationship between digitalization and tax avoidance gives a nuanced view of the effect. In fact, two opposing strands of literature emerge. On the one hand, researchers find a positive effect of digitalization on tax avoidance owing to the improvement of data transparency and the capacity of relevant stakeholders to oversee the financial management of the companies, making it harder to implement aggressive tax strategies. On the other hand, companies, with the use of innovative technologies, decrease their tax burden through mechanisms like profit shifting and the increase in cross-border transactions. This dichotomy highlights a clear tension in the literature and motivates our research question, particularly in the Moroccan and, more broadly, the MENA region, where the literature is still burgeoning. Further, the focus of the literature on developed and Asian contexts creates a gap in understanding how contextual factors such as institutional and regulatory environments shape the impact of digitalization on tax avoidance.

2.3.1. The Positive Effect Hypothesis

Xie and Huang (2023), using panel data of listed firms in the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock markets between 2009 and 2019, find that digital transformation significantly reduces corporate tax avoidance via the quality of the internal control systems. By automating business processes and management systems, digitalization improves the internal control of companies, reducing the divergence of interests between stakeholders and information asymmetry. It also generates data with tools like online cash registers and electronic invoices that help tax authorities to curb tax avoidance strategies.

Using data from Chinese listed firms, T. Guo et al. (2023) found that digitalization inhibits tax avoidance by improving information transparency and alleviating financial constraints. It enhances the quality of financial information and reduces the asymmetry between shareholders and managers, improving corporate governance.

Zhang and She (2024), after examining Chinese listed firms from 2007 to 2022, found that digitalization reduces tax avoidance through mechanisms related to three levels: technology, organizational, and environmental. For the technological level, digitalization improves resource allocation and strengthens companies’ innovation, making them less prone to tax avoidance behavior. For the organizational level, internal control quality is optimized, and data transparency is improved. At the environmental level, digitalization diminishes industry competition. The impact is more pronounced for companies at their growth phase with lower financial constraints.

While these studies directly confirm the negative association between digitalization and corporate tax avoidance, they show two key limitations. First, the focus almost exclusively on the Chinese context limits generalizability to other institutional contexts like the MENA region. Second, they tend to simplify the effect of corporate governance by treating it as a simple control variable rather than a core mechanism of curbing tax avoidance, in addition to their strong focus on transparency and internal control mechanisms. Studies by Xie and Huang (2023) show that these mechanisms curb managers’ opportunistic behavior, but they overlook the overwhelming organizational and financial costs of these strategies.

H1.

Digitalization is negatively associated with corporate tax avoidance.

2.3.2. The Negative Effect Hypothesis

Qu and Jing (2025) find that technology, particularly artificial intelligence (AI), enhances tax avoidance. The authors adopted the accounting tax difference (DDBTD) to measure tax avoidance and the frequency of artificial intelligence-related keywords in annual reports and found that the regression between this measure and AI is positive and statistically significant. They argue that the high costs of implementing AI in terms of highly skilled and qualified personnel, in addition to investments in material and software, push companies to engage in tax avoidance to make up for these costs.

Zhou et al. (2022) find that digitalization reduces tax stickiness, this relation being mediated by tax avoidance. This means that companies that are more digitalized are better equipped to respond to changes in their profit level and optimize their tax strategies correspondingly, especially in periods of less activity. Essentially, the authors find that, on the one hand, digital transformation augments tax avoidance as measured by book-tax difference (BTD) and accounting tax difference (DDBTD), and on the other, tax avoidance decreases tax stickiness by permitting firms to analyze vast quantities of data and identify the best strategies to optimize their tax burden and react swiftly. This means that firms become smarter and less rigid in responding to changes in their environment. The effect is more apparent for firms with weak internal control mechanisms and those situated in regions with low tax enforcement.

Chen et al. (2025) use a difference-in-difference approach by comparing firms that have adopted digital technologies to a treatment group that have not. They find a negative relation between digital technologies and the respect of tax legislation, the coefficient being negative and statistically significant at the 1% level. The authors argue that digitalization, by enhancing the flux of intangible transactions, makes it harder for tax authorities to monitor the tax compliance by enhancing the audit costs. They also find that in regions where the regulatory environment is stronger, digitalized firms are more prone to comply with their fiscal obligations.

This strand of literature suggests that digitalization creates avenues for aggressive tax strategies. The integration of technologies gives more insights to firms for opportunities of tax reduction; it finds that tax avoidance can also be a result of the initial costs of investment and a strategy for firms to recoup their initiated costs.

Nonetheless, the studies argue that the conclusions highly depend on the regulatory and governance environment, especially tax enforcement capacities and firm-specific characteristics. This suggests that digitalization positively impacts tax avoidance primarily when oversight capacities are weak or absent. Moreover, they tend to overlook the dynamic nature of tax avoidance mechanisms, which evolves and depends on the interaction between technology adoption, management behavior, and organizational strategies.

H2.

Digitalization is positively associated with corporate tax avoidance.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Sample Selection and Data Source

The sample selected for the study consists of listed firms in the Casablanca Stock Exchange due to data availability (Table 1). We limited the sample to the period from 2020 to 2024 because most firms started publishing exhaustive annual financial reports starting from 2020, particularly after the COVID-19 pandemic. The sample period of 2020–2024 was chosen because this interval captures key digitalization and regulatory shifts in Morocco, including the rollout of the “Digital Morocco 2030” strategy and the expansion of digital public services. Furthermore, data on firm-level digital transformation, governance, and tax reporting are reliably available and consistent from 2020 onward, which helps ensure credible measurement. Ending in 2024 allows us to include the most recent reforms and trends while avoiding historical institutional regimes that differ substantially from the current context.

Table 1.

Sample screening process.

The following criteria were adopted in order to select the final sample: the exclusion of financial and insurance companies due to their particular tax regimes, companies not consistently listed during the period, and companies that were removed from the stock market. Annual reports of the firms were found on the Moroccan Capital Market Authority (AMMC) website. After the treatment, 56 firms were selected, and 272 observations were obtained on which the analysis was applied. They are distrusted across three main sectors, with industry having the biggest share with 51.78% of firms, followed by service with 30.37% and service with 17.85% as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Sector distribution.

3.2. Variable Design

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

The variable chosen for measuring tax avoidance in this study is the book-tax differences (BTD). This measure aims to assess the mismatch between the result as calculated in the company accounts and the one declared by the tax administration (Desai & Dharmapala, 2006). In fact, it is the latter that serves as the taxable base and indicates the level of the firm’s profitability. When the difference is too big, it could alert the fiscal authorities and point to a potential tax avoidance strategy by the firm. The BTD is considered as more robust than other metrics like the Effective Tax Rate (ETR) as it gives a straightforward and direct measure of tax optimization. In fact, a decrease in ETR can happen passively without any active actions from the firms; this measure is linked to the tax rate imposed on specific sectors that can change according to government orientations (Dyreng et al., 2008). Nonetheless, even if BTD is considered as a robust measure of tax avoidance, it could also be subject to accrual-based earnings management. To ensure an even more pertinent analysis, we employed the DDBTD in the robustness tests, which is the residual of the regression of BTD on total accruals, isolating the discretionary part of the book-tax differences related to tax planning.

3.2.2. Independent Variable

Drawing on the literature, we measure this variable using the ratio of keywords related to digitalization divided by the total words in the annual reports. This proxy represents the company’s digital transformation. The higher this ratio, the higher the digitalization level of the firm. The paper uses the dictionaries developed by Mu et al. (2025), Cen and Lin (2025), and E. X. Liu and Dang (2025) (refer to Appendix A). This technique considers the annual report as a vitrine of the firm’s strategic vision, including its digital transformation level; it is aimed at all of its stakeholders, be it investors, financial analysts, or regulators. The textual method also captures subtleties and nuances that financial data cannot directly measure. The study also refers to T. Guo et al. (2023)’s method for treating the right-skewed distribution of word frequency by applying the natural logarithm of word frequency plus one. Using the natural logarithm transformation reduces the skewness in the sample, as some mention the digital keyword more frequently while others sharply less. Adding one to the formula aims to avoid the issue of calculating the logarithm of zero for companies that never mention any of the keywords. While this measure of digital transformation reflects the firm’s management commitment and their strategic vision, we acknowledge that it could be subject to managerial manipulation, as shown below in the limitations of our study.

3.2.3. Control Variables

The study controls for a set of factors that could affect tax avoidance level according to the related strand of literature. The selected variables are return on assets (ROA), the company size (Size), the leverage level (Lev), the company’s age (Age), the duality of CEO and chairman of the board (Dual), the percentage of equity by the first shareholder (Top1), the size of the board of directors (BoardSz), and the number of independent directors on the board (Indep). The variable definitions and formulas are detailed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Variable definitions.

3.3. Model Design

In order to study the effect of the digitalization variable on book-tax differences, the OLS regression with the fixed year and industry effect was applied, controlling for a set of variables. The econometric model is presented as follows:

BTDit = β0 + β1DIGit + β2ROAit + β3Levit + β4Ageit + β5Dualit + β6Top1it + β7BoardSzit + β8Indepit + β9Sizeit + εit

This baseline model may be subject to endogeneity issues. For example, sample selection bias could be present, as firms that have initiated digitalization may have other unobserved characteristics that influence their tax strategy not directly measured. It could also have a reverse causality issue with firms engaging in tax avoidance that may also adopt digitalization to signal compliance. Omitted variables may also be present, weakening the results.

To address these concerns, we have performed multiple robustness tests to ensure the validity of our conclusions. Concerning the sample selection bias, we used propensity score matching (PSM) by comparison between groups of firms in our sample, those above the median digitalization as a treatment group, and another as the control group. We also addressed the reverse causality issue and omitted variable bias by employing a two-stage least squares regression.

4. Research Results and Discussion

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

The descriptive statistics and VIF in Table 4 and Table 5 show that the mean of book-tax differences is −0.00474 with a minimum of −0.36594 and a maximum of 0.2265. Concerning the digitalization level measured by the DIG variable, the mean stands at 0.0000375 with a minimum of 0 and a maximum of 0.00184, which shows the variability within firms in the sample, with some having a high level of digitalization as measured by the frequency of digital-related keywords and others not yet embarking on the transformation journey.

Table 4.

Descriptive Statistics.

Table 5.

Variance inflation factor (VIF).

This result differs from that of Xie and Huang (2023) in the Chinese context and Chhaidar et al. (2023) in the European context. However, the descriptive statistics of the control variable remain consistent with those reported in the prior literature. The variance inflation factor (VIF) shows that the variables in the sample do not exhibit multicollinearity, as their respective VIF are less than 10, as advised by the literature (Marquardt, 1970).

4.2. Correlation Matrix

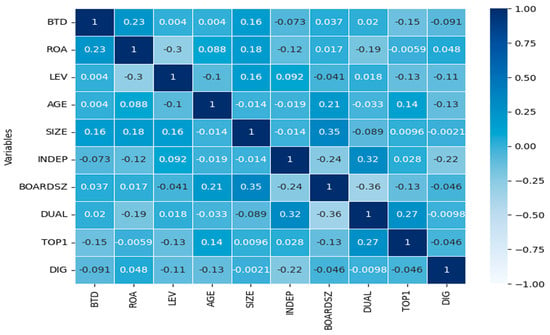

The correlation matrix in Figure 1 indicates that the relation between DIG and BTD is negative with a coefficient of −0.090721, giving an initial hint at the inverse relation between the two variables. The correlation between ROA and SIZE is positive, showing that bigger and more profitable companies are characterized by more tax aggressiveness, given their complex structure and the availability of resources to engage in optimized strategies. Concerning the governance variables, BoardSz, DUAL, and TOP1 seem to have a positive relation with BTD, showing that firms with a bigger board size, capital, and governance concentration have more difference between their accounting and fiscal results. In parallel, the independence of the board has a negative effect on BTD. The coefficients of AGE and LEV seem to be showing a small linear relation with book-tax differences.

Figure 1.

Correlation matrix.

4.3. Baseline Regression

To assess the impact of digitalization on tax avoidance as measured by the book-tax differences, we performed an OLS regression with a set of control variables with year and industry fixed effects in order to control for potential unobserved factors or heterogeneity at these levels and to neutralize their potential influence on the regression results. In fact, unobserved firm-specific characteristics like digital culture, internal control systems, and management practices are likely correlated with digitalization level, in line with previous studies (Zhou et al., 2022; Chen et al., 2025; Qu & Jing, 2025). To address potential outliers, we applied winsorization at the 1st and 99th percentiles for continuous variables in the sample, thereby reducing the influence of extreme values.

First, the regression model shows a significant negative relation between digitalization level and tax avoidance measured by the book-tax differences. The results show that the relation between DIG and BTD is negative and significant, showing that digitalization contributes to inhibiting tax avoidance at the corporate level, validating our main hypothesis. The model explains 14.2% of the variability of BTD and is statistically significant, capturing the meaningful effect of the predictors on the dependent variable.

An increase of one point in digitalization leads to a 40.84 decrease in the book-tax differences. Variables like SIZE and ROA are positively associated with the dependent variable, meaning that bigger and more profitable firms tend to engage in more aggressive tax behavior. We acknowledge that the coefficient on Dig in Table 6 (≈–40.85) appears large; this reflects both the scaling of Dig (a composite index) and the unit change measured. These additional results confirm the substantive conclusion that higher digital transformation is associated with substantially lower tax avoidance and help ensure that our findings are interpretable and practically meaningful.

Table 6.

OLS regression.

In parallel, governance characteristics such as CEO duality (DUAL) and board independence (Indep) significantly influence the book-tax differences. This means that firms where the CEO also serves as the chairman of the board exhibit greater tax aggressiveness. The proportion of independent directors on the board is negatively associated with BTD. Similarly, concerning the structure of the capital, firms with a higher ownership concentration in the hands of the largest shareholder tend to have less tax-aggressive behavior, showing their importance in monitoring firms’ strategy, especially their tax behavior.

4.4. Robustness Tests

4.4.1. Change in the Dependent Variable

In order to check the robustness of our results and to address potential bias, we adopted another measure of tax avoidance: the accounting-tax differences (DDBTD). This variable addresses the impact of accrual-based earnings management by removing its effect from the book-tax differences (Zhang & She, 2024). The variable is considered as the residual of the regression between the BTD and the total accruals. After replacing the dependent variable, the relation between digitalization and book-tax differences remains significant and negative at the 5% level, confirming the robustness of the results.

The results (Table 7) show that digital transformation (Dig) has a significant negative effect on tax avoidance (–35.6185, p = 0.038), indicating that higher levels of digitalization reduce tax avoidance. ROA, Size, firm age (Age), and CEO duality (Dual) have significant positive effects on tax avoidance. In contrast, ownership concentration (Top1) and board independence (Indep) exhibit significant negative effects, highlighting the role of strong governance in curbing tax avoidance. Other variables, such as Board size (BoardSz) and leverage (Lev), are not significant. The model explains approximately 12.6% of the variation in tax avoidance (R2 = 0.126).

Table 7.

Regression with DDBTD.

4.4.2. Sample Selection Bias

To address sample selection bias, we employed propensity score matching (PSM), which is considered a robust method to control for endogeneity issues, particularly selection bias. Drawing on the literature, especially Zhang and She (2024), we consider companies with a digitalization score above the median as the treatment group and those below as the control group. For the matching method, we chose the nearest neighbor method as used by Chen et al. (2025). The regression of DIG on BTD shows a significant negative relationship, with a negative coefficient of −0.0213 that is significant at the 5% level, consistent with the findings of the baseline regression.

As showing in Table 8, The results indicate that digital transformation (Dig) has a negative and statistically significant effect on tax avoidance (–0.0213, p = 0.012), suggesting that higher levels of digitalization reduce tax avoidance. ROA is positively associated with tax avoidance (0.3543, p < 0.001). Leverage (Lev) and CEO duality (Dual) also show positive and significant effects. In contrast, ownership concentration (Top1) and board independence have significant negative coefficients, implying that stronger governance mechanisms reduce tax avoidance. Other variables, including Size, Age, and Board size, are not statistically significant. The model explains about 21% of the variation in tax avoidance (R2 = 0.208).

Table 8.

Propensity score matching regression.

4.4.3. Endogeneity

Drawing on Zhang and She (2024), we apply a two-stage least squares regression (2SLS) to test for a potential reverse causality between book-tax differences and the level of digitalization. To isolate the exogenous variation in DIG, we construct two instrumental variables: IV1, measuring the mean digitalization level of other firms in the same industry and city, and IV2, defined as the cube of the difference between each firm’s digitalization level and the mean of its industry and province, capturing nonlinear effects and extreme deviations. Using these instruments, we predict the value of the DIG purged of endogeneity, which is then employed in the second-stage regression.

In line with Sun et al. (2022), we conduct the Sargan test to assess instrument validity. The p-value of 0.302 indicates that we do not reject the null hypothesis of exogeneity, suggesting IV1 and IV2 are valid instruments. The first-stage F-statistic is 120, exceeding the conventional threshold of 10 (Staiger & Stock, 1994), confirming the strength of the instruments.

The results support the robustness of the main findings, showing a negative relation between digitalization and tax avoidance, significant at the 5% level after correcting for potential endogeneity.

In the first-stage regression (Table 9), both instruments are significantly associated with DIG, confirming their relevance. In the second stage, the coefficient of DIG is negative and statistically significant (–52.083), indicating that higher levels of digital transformation are associated with lower tax avoidance (BTD). Among the control variables, ROA positively influences BTD, while ownership concentration (Top1) and board independence (Indep) reduce it. Leverage (Lev) also shows a positive relationship with tax avoidance. The model explains 76% of the variation in DIG (first stage) and 17% in BTD (second stage), confirming the robustness of the instruments and highlighting the mitigating effect of digital transformation on tax avoidance.

Table 9.

2SLS regression.

The study concludes that digitalization significantly influences tax avoidance at the corporate level. The findings provide several important insights that enlighten firms’ managers and stakeholders concerning the benefits of embarking on a digital transformation journey.

Our results support hypothesis H1 and align with the findings of Xie and Huang (2023), T. Guo et al. (2023), and Zhang and She (2024), showing that digitalization contributes to the increase in financial transparency and the amelioration of companies’ internal control systems.

Other variables also have a significant impact on tax avoidance level. Firm characteristics like ROA and Size have a positive impact on the book-tax differences, showing that more profitable and bigger firms engage in more tax-aggressive behavior. Governance-related variables—including CEO duality (DUAL), ownership concentration (TOP1), and board independence (INDEP)—also influence the avoidance level. Firms with more independent administrators on their board and whose first shareholder has a bigger share of equity tend to have fewer book-tax differences. In parallel, those where the general director is also the chairman of the board tend to have a more tax-aggressive strategy.

The robustness tests that were performed validate the results of the baseline regression. In fact, when using another measure of tax avoidance (DDBTD), the negative relation with digitalization remains significant. The PSM and 2SLS tests are also conclusive, their results being in line with the main findings of the regression.

5. Conclusions

This study uses data from 56 listed firms on the Casablanca Stock Exchange over the period 2020–2024 and employs a panel data regression method. The results show that digitalization negatively impacts corporate tax aggressiveness, supporting the view that digitalization is a cornerstone for upgrading internal processes and signals more transparency of financial information to the different stakeholders. By enabling more accountability and integrity of financial information, digitalization leads to fewer avenues for aggressive tax strategies.

The study also shows the role of stronger governance structure in mitigating tax avoidance, calling for a generalization of independent directors and the separation of CEO and chairman positions. These governance mechanisms mitigate potential tax aggressiveness and, analyzed through the lens of the agency theory, contribute to the decrease in information asymmetry between the shareholders and the managers. It shows that firms’ digital transformation should not be seen as a simple investment in infrastructure but rather a strategic choice for increasing financial data transparency and enabling greater accountability.

From a theoretical standpoint, the results show that digitalization reduces corporate tax aggressiveness, in line with previous studies. The negative relation between digital transformation and book-tax differences is consistent with the agency theory that posits that the promotion of information transparency decreases the asymmetry of information between the managers and shareholders, acting as a strong internal control mechanism. The increase in the flow and quality of data constrains the discretion of managers and pushes them to align with the best interest of shareholders and tax authorities. It also confirms the hypotheses of the signal theory by sending strong positive signals to stakeholders, showing that the firm is in line with its legal and contractual obligations, which directly fosters trust.

The study also contributes to the strand of literature related to corporate governance. In fact, it found that the separation of the role between CEO and chairman has a strong disciplining effect by preventing phenomena like the entrenchment of management, when the executive uses company resources for their own personal gain. It also shows the benefit of implementing independent administrators on companies’ boards, which has a disciplining effect and contributes to the alignment of shareholders’ interests with those of managers.

From a practical standpoint, the findings show the need for policymakers to support companies in their digital transformation by providing technical and financial support, as this contributes to the overall health of the financial system and the broadening of the tax base, since digitalized companies tend to be more tax-compliant.

The results also call for tax authorities to align with this transformation by upgrading their own internal digital capabilities, especially by upgrading their digital infrastructure and adopting risk-based systems to improve tax audit effectiveness. This would help them to ensure interoperability with firms’ internal systems by promoting tools like SAF-T, which aims to facilitate the exchange of tax data by providing a standardized structure of tax files (Mihaela & Alin, 2023). In addition, investing in human capital is also crucial to effectively analyze the complexity of the digital economy and effectively detect tax avoidance schemes.

It also calls for managers and corporate leaders to view digitalization as an investment in their reputation and the overall improvement of their internal processes. It should be complemented with strong governance structures like independent directors and separation of CEO and chairman roles to align with the best international practices and reduce opportunistic behaviors.

It also shows the need to encourage firms to adopt digital tax technologies like electronic filing and electronic invoicing to improve compliance and reduce tax risks. This calls for the conduction of studies to understand factors of adoption by mobilizing frameworks like the diffusion of innovation or the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT).

Among the main limits of the study is the measure of digitalization adopted in the paper. In fact, the frequency of digital-related keywords in annual reports is a method that is subject to manipulation by management. For example, if a company wanted to send a signal to its stakeholder that it is more digital, it would use more keywords in its annual report. Other measures are available in the literature, like the proportion of intangible assets related to digitalization or the adherence to digital platforms allowing for the use of various technologies (Chen et al., 2025). The nature of the sample could also be seen as a limit, as listed firms are mainly large companies as opposed to unlisted small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) that could show different results as they face different regulatory and resource constraints. The focus on a developing country could also be a limit, as developed countries have more developed corporate digitalization levels and tax administration systems that strongly enforce tax compliance through predictive control systems.

The analysis could also be enriched by analyzing the level of digitalization of non-listed firms to grasp a more nuanced view of the phenomenon. The use of a qualitative approach could add value by asking the relevant stakeholders, who could give details about the reasons behind their firm engagement in digitalization and how it truly affected the activity and performance of its various departments. They could also develop other measures of digitalization by including detailed investments in intangible digital assets or software, in addition to including mediating mechanisms like internal control quality or financial constraints faced by the firm.

The Moroccan context provides an illustrative backdrop. The country has integrated a series of plans aimed at strengthening its adherence to the digital economy and providing the public sector with tools to best serve citizens with a timely and seamless interaction. The most recent one is Digital Morocco 2030, which aims to digitalize public services and improve the e-government ranking of the country in addition to boosting the digital economy by creating 240,000 direct jobs and contributing 100 billion MAD to the GDP by 2030. The strategy leverages state-of-the-art technologies like artificial intelligence to improve public service quality and interaction with the private sector. The revision of the “Code of Good Governance Practices” in 2025 is also a step toward strengthening governance in Moroccan firms, especially through the integration of independent directors on the boards, the reinforcement of accountability mechanisms, and the implementation of regular evaluation and financial transparency.

Likewise, the Directorate General of Taxes (DGI) has put in place an ambitious plan spanning from 2024 to 2028 aimed at improving its relationship with taxpayers and promoting voluntary compliance and tax equity. At the crux of this plan is the digital capabilities of the DGI with two facets: the technical, based on the technological infrastructure, and the non-technical, consisting of its human capital. Among its priorities is to mobilize all the fiscal potential of the country by improving the integrity of taxpayer registers, improving declaration conformity, and adopting a predictive tax control system relying on robust algorithms and technologies like artificial intelligence and big data (DGI (Direction Générale des Impôts), 2024).

Future research could explore the underlying mechanisms of the relation between the two variables, like the quality of internal control, the environment characteristics, or even internal organizational culture.

Overall, the study underscores the potential of digital transformation as a governance tool that not only reduces tax avoidance but also contributes to building more transparent, accountable, and resilient financial systems in the Moroccan context.

In conclusion, the findings provide valuable insights for companies, policymakers, and managers to engage in digitalization and to encourage the setting of more independent governance structures.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A., N.M., K.M. and A.M.; methodology, A.A., N.M., K.M. and A.M.; software, A.A.; validation, A.A., N.M. and K.M.; formal analysis, A.A. and K.M.; investigation, A.A.; resources, A.A., N.M., K.M. and A.M.; data curation, A.A., N.M. and K.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.; writing—review and editing, N.M., K.M. and A.M.; visualization, A.A.; supervision, N.M., K.M. and A.M.; project administration, A.A. and K.M.; funding acquisition, A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in the Autorité Marocaine du Marché de Capitaux (AMMC) repository at https://www.ammc.ma. These data were derived from the following resources available in the public domain: (1) the official website of the Autorité Marocaine du Marché de Capitaux (AMMC) (https://www.ammc.ma), and (2) the annual reports published on the respective firms’ official websites.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

| Digitalization Dictionary | Source |

| 3D printing, AI facial recognition, Augmented reality, Autonomous driving, Automatic production, B2B, B2C, Big data, Billion-level concurrency, Bitcoin, Biometrics, Biometric technology, Blockchain, Brain-like computing, Business decision support, Business intelligence, C2B, C2C, Cloud computing, Cognitive computing, Consensus algorithm, Consensus mechanism, Consortium blockchain, Contactless payment, Converged architecture, Credit reporting, Credit scoring, Cyber-physical systems, Data cleaning, Data collection, Data-driven, Data extraction, Data integration, Data management, Data mining, Data security, Data sharing, Data storage, Data stream, Data visualization, Decentralization, Deep algorithm, Deep learning, Differential privacy technology, Digital currency, Digital finance, Digital innovation, Digital marketing, Digital potential, Digital products, Digital services, Digital terminal, Digital tracking, Distributed computing, Distributed database, Distributed file system, Distributed storage, Distributed system, E-commerce, EB-level storage, Encryption algorithm, Exabyte-scale storage, Facial recognition, Financial technology, Fintech, Flexible production, Fusion architecture, Graph computing, Green computing, Group services, Heterogeneous data, High competition, Human–computer interaction, Identity verification, Image analysis, Image understanding, In-memory computing, Industrial interconnection, Industrial Internet, Industry 4.0, Information platform, Information system, Information-physical system, Intelligent agriculture, Intelligent animal husbandry, Intelligent cultural tourism, Intelligent customer service, Intelligent data analysis, Intelligent environmental protection, Intelligent investment advisory, Intelligent logistics, Intelligent manufacturing, Intelligent marketing, Intelligent robots, Intelligent warehousing, Internet connection, Internet finance, Internet healthcare, Internet of Things, Live streaming, Machine learning, Memory computing, Mini program, Mixed reality, Mobile application, Mobile Internet, Mobile payment, Multi-party secure computing, Natural language processing, Network channel, Neural networks, NFC payment, Numerical control, O2O (Online-to-Offline), OA system, Official account, Online and offline sales, Online banking, Online marketplace, Online payment, Online sales, Open banking, Payment systems, Personalization, Private domain, Quantitative finance, Robotics, Semantic search, Sensors, Server network, Smart agriculture, Smart clothing, Smart contracts, Smart customer service, Smart energy, Smart environmental protection, Smart financial contracts, Smart grid, Smart healthcare, Smart home, Smart investment advisory, Smart marketing, Smart transportation, Smart travel, Smart wearables, Social media, Social network, Speech recognition, Stream computing, Text analysis, Text mining, Third-party payment, Traffic, Unmanned retail, Virtual machine, Virtual products, Virtual reality, Virtualization, Visualization, Voice recognition. | Mu et al. (2025), Cen and Lin (2025), E. X. Liu and Dang (2025) |

References

- Allingham, M. G., & Sandmo, A. (1972). Income tax evasion: A theoretical analysis. Journal of Public Economics, 1(3), 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alm, J. (2021). Tax evasion, technology, and inequality. Economics of Governance, 22(4), 321–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almutairi, A. M., & Abdelazim, S. I. (2025). The impact of CSR on tax avoidance: The moderating role of political connections. Sustainability, 17(1), 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshabibi, B., Pria, S., & Hussainey, K. (2022). Nationality diversity in corporate boards and tax avoidance: Evidence from Oman. Administrative Sciences, 12(3), 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braithwaite, V. (2003). Who’s not paying their fair share: Public perceptions of the Australian tax system. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 38(3), 323–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cen, T., & Lin, S. (2025). Digital transformation and corporate innovation in SMEs. Systems, 13(7), 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S., Liu, Z., & Cai, W. (2025). Digital transformation and tax compliance in Chinese industrial sector. International Review of Financial Analysis, 102, 104116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhaidar, A., Abdelhedi, M., & Abdelkafi, I. (2023). The effect of financial technology investment level on European banks’ profitability. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 14(3), 2959–2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, M. A., & Dharmapala, D. (2006). Corporate tax avoidance and high-powered incentives. Journal of Financial Economics, 79(1), 145–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DGI (Direction Générale des Impôts). (2024). Plan stratégique 2024–2028. Direction Générale des Impôts, Ministère de l’Économie et des Finances. [Google Scholar]

- Doghmi, H. (2020). La capacité de mobilisation des recettes fiscales au Maroc. Bank Al Maghrib. [Google Scholar]

- Dyreng, S. D., Hanlon, M., & Maydew, E. L. (2008). Long-run corporate tax avoidance. The Accounting Review, 83(1), 61–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldomiaty, T. I., Apaydin, M., El-Sehwagy, A., & Rashwan, M. H. (2023). Institutional quality and firm-level financial performance: Implications from G8 and MENA countries. Cogent Economics & Finance, 11(1), 2220249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elia, S., Giuffrida, M., Mariani, M. M., & Bresciani, S. (2021). Resources and digital export: An RBV perspective on the role of digital technologies and capabilities in cross-border e-commerce. Journal of Business Research, 132, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enofe, A., Embele, K., & Obazee, E. P. (2019). Tax audit, investigation, and tax evasion. Research Journal of Finance and Accounting, 5(4), 47–66. [Google Scholar]

- Gallemore, J., Maydew, E. L., & Thornock, J. R. (2014). The reputational costs of tax avoidance. Contemporary Accounting Research, 31(4), 1103–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godard, L., & Schatt, A. (2004). The determinants of “quality” of the French board of directors (Working paper FARGO). Université de Bourgogne, Centre de Recherche en Finance, Architecture et Gouvernance des Organisations (FARGO). [Google Scholar]

- Guo, T., Cheng, H., Zhou, X., Ai, S., & Wang, S. (2023). Does corporate digital transformation affect the level of corporate tax avoidance? Empirical evidence from Chinese listed tourism companies. Finance Research Letters, 57, 104271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X., Li, M., Wang, Y., & Mardani, A. (2023). Does digital transformation improve the firm’s performance? From the perspective of digitalization paradox and managerial myopia. Journal of Business Research, 163, 113868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinemann, M., & Stiller, W. (2024). Digitalization and cross-border tax fraud: Evidence from e-invoicing in Italy. International Tax and Public Finance. [Google Scholar]

- Hess, T., Matt, C., Benlian, A., & Wiesbock, F. (2016). Options for formulating a digital transformation strategy. MIS Quarterly Executive, 15(2), 6. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1979). Rights and production functions: An application to labor-managed firms and codetermination. The Journal of Business, 52(4), 469–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kateb, I., Nafti, O., & Zeddini, A. (2025). How to improve the financial performance of Islamic banks in the MENA region? A Shariah governance perspective. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 20(6), 2559–2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, E. X., & Dang, L. (2025). Digital transformation and debt financing cost: A threefold risk perspective. Journal of Financial Stability, 76, 101368. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q., Tian, G., & Wang, X. (2011). The effect of ownership structure on leverage decision: New evidence from Chinese listed firms. Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy, 16(2), 254–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loderer, C., & Waelchli, U. (2010). Firm age and performance (Working paper). University of Bern. [Google Scholar]

- Marquardt, D. W. (1970). Generalized inverses, ridge regression, biased linear estimation, and nonlinear estimation. Technometrics, 12(3), 591–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, P. J., & Weir, C. (2009). Agency costs, corporate governance mechanisms and ownership structure in large UK publicly quoted companies: A panel data analysis. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 49(2), 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihaela, I. C., & Alin, H. G. (2023). Analysis of the economic entities’ perception over the implementation of the Saf-T. In International conference on economics and social sciences (pp. 113–129). Springer Nature Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- Mu, X., Chen, D., & Zhang, H. (2025). The impact of digital transformation on the sustainable development of enterprises: An analysis from the perspective of digital finance. Journal of Applied Economics, 28(1), 2464488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2020). Tax administration 3.0: The digital transformation of tax administration. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Piccinini, E., Hanelt, A., Gregory, R., & Kolbe, L. (2015, July 5–9). Transforming industrial business: The impact of digital transformation on automotive organizations. 19th Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems (PACIS), Singapore. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, G., & Jing, H. (2025). Is new technology always good? Artificial intelligence and corporate tax avoidance: Evidence from China. International Review of Economics & Finance, 98, 103949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, G., & Lanis, R. (2007). Determinants of the variability in corporate effective tax rates and tax reform: Evidence from Australia. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 26(6), 689–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S. A. (1977). The determination of financial structure: The incentive-signalling approach. The Bell Journal of Economics, 8(1), 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slemrod, J., & Yitzhaki, S. (2000). Tax avoidance, evasion, and administration (NBER working paper No. w7473). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Souguir, Z., Lassoued, N., Khanchel, I., & Bejaoui, E. (2025). Behind the screens: Digital transformation and tax policy. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(7), 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staiger, D. O., & Stock, J. H. (1994). Instrumental variables regression with weak instruments (NBER working paper No. w4789). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Stiglitz, J. E. (1985). The general theory of tax avoidance. National Tax Journal, 38(3), 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C., Lin, Z., Vochozka, M., & Vincúrová, Z. (2022). Digital transformation and corporate cash holdings in China’s A-share listed companies. Oeconomia Copernicana, 13(4), 1081–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titman, S., & Wessels, R. (1988). The determinants of capital structure choice. The Journal of Finance, 43(1), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, P. C., Broekhuizen, T., Bart, Y., Bhattacharya, A., Qi Dong, J., Fabian, N., & Haenlein, M. (2021). Digital transformation: A multidisciplinary reflection and research agenda. Journal of Business Research, 122, 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vial, G. (2019). Understanding digital transformation: A review and a research agenda. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 28(2), 118–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, K., & Huang, W. (2023). The impact of digital transformation on corporate tax avoidance: Evidence from China. Discrete Dynamics in Nature and Society, 2023, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Yermack, D. (1996). Higher market valuation of companies with a small board of directors. Journal of Financial Economics, 40(2), 185–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, H., Yang, M., & Chan, K. C. (2022). Does digital transformation enhance a firm’s performance? Evidence from China. Technology in Society, 68, 101841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q., & She, J. (2024). Digital transformation and corporate tax avoidance: An analysis based on multiple perspectives and mechanisms. PLoS ONE, 19(9), e0310241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S., Zhou, P., & Ji, H. (2022). Can digital transformation alleviate corporate tax stickiness: The mediation effect of tax avoidance. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 184, 122028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).