Abstract

In the context of rising uncertainty and financial crises, the roles of financial advisors are evolving beyond technical compliance, particularly in household contexts. This article introduces a novel perspective by highlighting how these professionals contribute to resilience and stability at all levels of society by building financial literacy and acting as human barriers against systemic risk. From the datasets retrieved from Web of Science and Scopus, a final curated sample of 102 peer-reviewed articles was retained following thematic refinement and in-depth human filtering. After data harmonisation, a bibliometric analysis was conducted through VOSviewer, identifying five key thematic clusters. Beyond cartographic description, a rigorous thematic exploration was conducted. We advance an interpretive architecture consisting of mechanisms (M1–M4), advice-to-outcome pathways (P1–P3), and a conditional context (Conditions of Success (CS), Failure points (F) and Moderating Factors (MF)), enabling integrative inference and cumulative explanation across an otherwise heterogeneous corpus. Results show that financial advisors mitigate risk by educating clients, guiding decisions, and turning complexity into usable judgment. They also bear risk; as human barriers, they channel and transform these pressures through their professional practice, returning stabilizing effects to households and, by extension, to the wider financial system.

1. Introduction

Financial crises have become more frequent and persistent, with long-lasting effects that extend beyond markets and institutions. Risk is now widely distributed across society, and households have emerged as key sites of exposure and vulnerability. Their routine financial behaviours (paying bills, servicing debt, saving, investing) feed into global flows of capital and credit, making household fragility structurally relevant (Santoso & Sukada, 2009; Bryan et al., 2016; OECD, 2022; Tinel, 2021). Protecting household resilience is therefore not only a private concern but also a matter of monetary, fiscal, and regulatory governance.

As financial rules grow more complex, compliance and decision costs increasingly fall on citizens, especially in tax-sensitive contexts. Legislators seek to close loopholes and strengthen revenue collection, but these measures often impose disproportionate burdens on households, generating demand for professional guidance (European Parliament. Directorate General for Internal Policies of the Union, 2023; Forest & Sheffrin, 2002; OECD, 2024). In practice, financial professionals help individuals translate regulations into actionable choices, improve planning, and reduce errors and penalties. Yet access to such support remains uneven, especially in vulnerable contexts (Musimenta, 2020; Sun et al., 2022).

In everyday life, there are few intermediaries between the state and the individual, yet in practice, professionals often help people navigate daily complexities. In finance, this role is carried out by advisors who guide households through rules, risks, and decisions. They strengthen household resilience and act as key intermediaries between citizens and systems, translating technical regulations into actionable knowledge (Lai, 2016).

Our motivation was originally to address how professionals legally authorized to provide ex-ante financial and tax advice benefit both governments and households. This is because for governments, the primary administrative objective is to secure revenues efficiently and fairly through voluntary compliance and effective enforcement (Internal Revenue Service, 2025a; International Monetary Fund, 2022; European Commission, 2020, 2021). For households, ex-ante advice improves planning, tax compliance, and financial decision-making, potentially lowering cash-flow volatility and errors.

Working definitions. To build a conceptual foundation, we define the financial advisory function as the professional activity of guiding households in planning, tax optimization, and risk management, limited to those legally authorized to provide pre-declaration (ex-ante) advice. This includes CPAs entitled to act before the U.S. Internal Revenue Service (Internal Revenue Service, 2025b), as well as accountants and advisors recognized jointly by Accountancy Europe (2025). Internationally, IFAC represents professionals across business, taxation, and advisory roles, including through the Institute for Tax Advisors and Accountants (International Federation of Accountants, 2025). In line with this scope, we exclude ex-post functions performed mainly by auditors and attorneys, such as assurance, disputes, and litigation. Herein, the term “financial advisor” designates professionals legally entitled to provide financial advice, reflecting our choice of the most integrative and regulation-grounded term. In this study, the “system” refers to the institutional and structural environment that shapes financial activity. It includes regulatory bodies, taxation frameworks, economic trends, and socio-technological forces such as digitalization and globalization. Households refer to non-corporate actors, such as families or individuals, whether grouped or alone, who interact with financial systems through income, taxation, financial planning, and advisory support. Additionally, this analysis adopts the perspective of natural persons, rather than legal entities.

This study responds to these challenges by synthesizing the literature through a combined bibliometric and thematic review. We build a conceptual framework that specifies how advisors act at the boundary between households and the system, focusing on four mechanisms: compliance translation, anticipatory cash-flow planning, behavioural coaching, and product/tax intermediation. These mechanisms provide ex-ante support for households and structure our subsequent analysis.

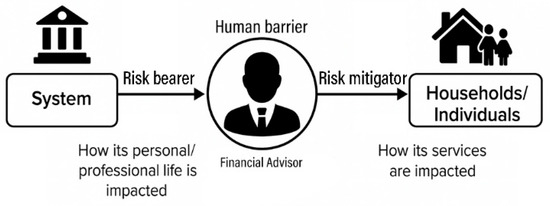

Figure 1 illustrates this dual positioning: advisors mitigate household risks through everyday financial guidance while at the same time bearing professional risks related to gender/pay gaps, training deficits, digitalization and AI, work–family pressures, corporatization, and weak oversight. This socio-professional stress can affect both the quality and the availability of advice.

Figure 1.

Advisors as a human barrier: risk bearer in their socio-professional environment and risk mitigator toward households/individuals. Source: Authors’ elaboration.

The first objective of this study is to identify prevailing research trends, thematic evolutions, and conceptual linkages through bibliometric analysis to visualise the network that the scholarly discourse draws. The second and primary objective of this study is to build on the previous analysis by examining emerging research trends through keyword visualisation. The study addresses four research questions:

RQ1: What is the intellectual and thematic structure of financial advisors’ roles, and does it cohere into an ex-ante, human-interface framework?

RQ2: How have advisors’ roles evolved beyond traditional investment consultancy, and through which mechanisms do they mitigate household risk, or, under what conditions, fail to do so?

RQ3: To what extent do advisors act as educators improving financial literacy, and how does this translate into fewer errors, reduced penalties, and improved cash flows?

RQ4: How do regulation, technology, and globalisation shape advisors’ exposure to risk, and under what conditions do these factors amplify or dampen transmission across households?

This paper is structured into five sections. Section 1 (Introduction) establishes the study’s context, theoretical grounding, and research significance. Section 2 (Research Method) details the systematic approach, including data collection and analysis techniques. Section 3 (Descriptive Bibliometric Analysis) examines the research’s geographical and institutional distribution, mapping the contributions of key countries, academic institutions, and influential authors. Section 4 (Bibliometric Analyses of the Topics Researched) provides a thematic overview of the scholarly discourse by examining keyword clusters, temporal distributions, and density visualisations. Within this section, Section 4.4 (Results) consolidates the conclusions drawn from each cluster previously examined in detail, while Section 4.5 (Discussion) develops the broader perspective by outlining research trends, advancing testable propositions, and considering additional factors that shape the risk-mitigation system. Finally, Section 5 (Conclusions) provides an overarching synthesis of the findings and directly addresses the research questions, highlighting their implications for scholarship and practice.

2. Research Method

2.1. Keywords and Data Selection

This study applies a mixed research strategy using Scopus and Web of Science (WoS) to ensure transparency, reproducibility, and reliable insights. We combine bibliometric performance and science mapping with thematic analysis to identify constructs, mechanisms, and pathways. Consistent with a theory-building review, these insights are integrated into a framework and translated into testable propositions (Post et al., 2020; Snyder, 2019; Torraco, 2005). WoS and Scopus were chosen as the leading bibliometric databases, noted for their rigorous data integrity and indispensable value in co-citation networks, keyword co-occurrence analysis, and institutional collaboration mapping.

To conduct this study, the following Boolean string was used in each database: role AND (“accountant” OR “CPA” OR “certified public accountant” OR “financial advisor” OR “tax advisor*” OR “financial consultant*” OR “tax consultant*”) AND (“household*” OR “famil*”). In WoS, the search constraints were based on the topic. At the same time, in Scopus, the search strategy was more specific and involved the search criteria based on the articles’ titles, abstracts, and keywords. The search string was carefully designed to balance precision with thematic breadth. The term “role” helped identify how these experts contribute to managing financial risk. To ensure thematic diversity and capture all professionals potentially involved in personal financial advisory, the query included both formal terms (e.g., “CPA,” “certified public accountant”) and colloquial or functional variants (e.g., “tax consultant,” “financial consultant”). This inclusive approach responds to the fragmentation in terminology across disciplines while maintaining a clear focus on the advisory function. Terms like “household*” and “famil*” were added to explore how advisors influence family-level financial decisions, where vulnerability to risk is often highest. The use of these terms was based on preliminary test searches, given the study’s focus on the niche context of how financial advisors operate within family and household environments; even when these consist of a single person, we selected terms that better reflect this targeted scope.

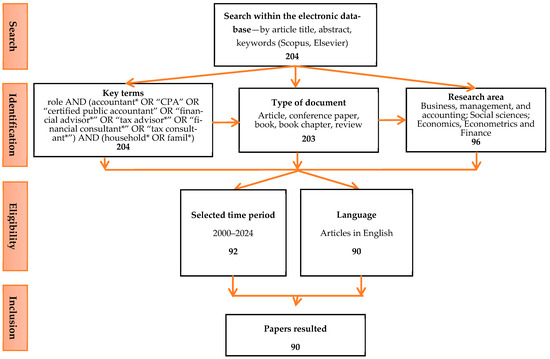

Covering the period from 2000 to 2024, the review drew on the literature from WoS and Scopus, in the form of journal articles, reviews, proceedings, and book chapters. To ensure homogeneity and availability, the search was limited to English-language publications. The data extraction for WoS and Scopus was conducted on 19 December 2024. Figure 2 illustrates the entire process of refining the search strategy in Scopus.

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of systematic selection of studies from Scopus. Source: Data processed by authors.

When searching Scopus, the first search included the research areas of business, management, accounting, social sciences, economics, econometrics, and finance, covering global geographical contexts. This search yielded 96 academic works. A filtering procedure was employed to select the literature appropriate to the study scope, narrowing the search by an additional 14 publications. Thus, 90 research papers formed the final dataset in line with the established criteria for inclusion.

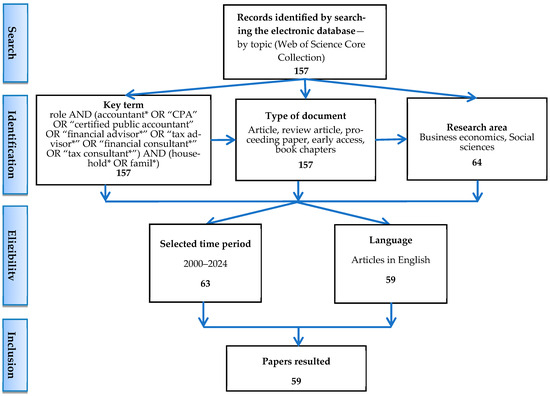

The same refined search strategy was executed within the WoS database to uncover relevant manuscripts (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Flow diagram of systematic selection of studies from WoS. Source: Data processed by authors.

In WoS, the filtering process focused on the field of business and economics, and the results of the first search produced 157 scientific papers. As shown in Figure 3, after the multi-stage filtering process, 98 articles were considered ineligible, mainly because of the restricted research area, and subsequently excluded. This inclusion and exclusion process produced 59 relevant research papers. Such careful methodology guaranteed the inclusion of academic publications directly related to the purpose of the study.

2.2. Method of Data Refining and Data Analysis

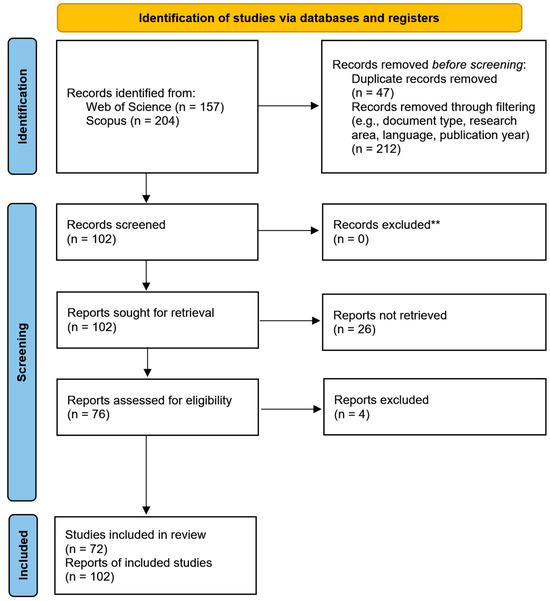

Following the database-specific filtering stages, the remaining records were merged and screened using an adapted PRISMA flow structure, as shown below (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Adapted PRISMA 2020 flow diagram illustrating the overall record selection process. Source: Adapted from Page et al. (2021). ** = no records were excluded.

To ensure transparency and methodological clarity in our systematic selection process, we adapted the PRISMA 2020 framework to illustrate the global search screening and inclusion steps. While PRISMA was originally designed for systematic reviews involving empirical data, its principles have been successfully adjusted in bibliometric studies to document inclusion logic and filtering procedures clearly (Page et al., 2021). This adapted version provides a visual and structured overview of the literature selection process, in line with best practices for transparency in evidence mapping and bibliometric methodology (Donthu et al., 2021).

Out of the 361 records retrieved from the two databases (157 from WoS, 204 from Scopus), 212 were automatically excluded based on database-specific filtering criteria (publication year, language, document type, and subject area). An additional 47 duplicate records were identified and removed using the Biblioshiny for Bibliometrix (version 4.1.2) deduplication tool. Of these, 76 full-text articles were successfully retrieved, while 26 could not be accessed in full. In this regard, a total of 102 articles were retained for the bibliometric analysis. Out of these, 76 articles were available in full text and were closely examined in Section 4.3. The remaining 26 articles, for which full-text access was not possible, were included alongside the 76 only in the bibliometric component. This approach is consistent with standard bibliometric procedures, which rely on metadata rather than full-text access for trend mapping and co-occurrence analysis (Donthu et al., 2021; Aria & Cuccurullo, 2017; Zupic & Čater, 2015). Seventy-two full-text articles met the inclusion criteria for thematic synthesis and citation. The appraisal mechanism was based on four predefined criteria: (1) indexing in Scopus or Web of Science as a proxy for peer-review and formal academic standards; (2) alignment with the economic or financial domain; (3) classification as a journal article or proceedings paper or book chapter; and (4) thematic relevance through direct reference to financial advisors or accountants. Four articles were reviewed in full but ultimately excluded from citation due to thematic irrelevance, as they focused on advisors in contexts such as healthcare (e.g., diabetes), industrial control systems, and shelter/appliance markets, rather than economics. Those four articles did not meet the inclusion criteria. Thematic synthesis was applied exclusively to this subset. Given the interpretative nature of thematic analysis, some subjectivity is acknowledged; however, the objective was not to evaluate methodological design but to extract meaningful conceptual insights from thematically grouped literature.

To guarantee consistency and enable precise analysis, keyword standardisation was performed once the database was revised and merged. The plural and singular forms were combined during this procedure. For example, variations like “financial advisor/s”, “ecology/ies”, “family business/es”, “auditor/s”, “manager/s”, “mentors/ing”, “sme/s” were consolidated. Furthermore, synonym terms or related terms were unified (e.g., “financial advice/formal advisor/financial advice/financial advisor”, “family interfering work/work-family conflict/work-interfering-family/work-life balance/work-family balance”, “job stress/stressor/stress”, “increasing savings/factors influencing savings/savings”, “financial literacy/financial sophistication/financialisation/financial education”, “religious orientation/religion”, “management accounting change/managerial accounting practices/management accountants/management accounting”, “accounting profession/chartered accountant/accountants/cpa/accountant”, “forensic accounting/public accounting/accounting practices/accounting mechanism/accounting principles/accounting domain/accounting”, “family firms/family ownership/small family business/family business”, “code of conduct/ethical attitude/ethical dimension/professional code/ethics”, “value of advice/financial advice/advice”, “regulatory context/regulation”, “overall justice/justice”, “subjective well-being/psychological well-being/well-being”, “perceived organisational support/organisational support/work conditions/organizational justice/organisational attributes/organisational environment”, “entrepreneurial skills/entrepreneurship”, “role conflict/role theory/role clarity/household roles/role ambiguity/role conflict/role/roles”, “turnover intentions/voluntary turnover/turnover”, “sustainable development/sustainability reporting/sustainability”, and “tax/taxes/taxation”).

After this standardisation process, the data were ready for further examination. The analytical phase included descriptive bibliometric analysis and subject exploration, including thematic and keyword co-occurrence analysis.

In Section 4.3, the gathered literature is extensively interpreted through a proposed architectural model (comprising Mechanisms (M), Pathways (P), Conditions for Success (CS), Failure points (F), and Moderating Factors (MF)), which provides interpretive uniformity for the thematic analysis and establishes a coherent conditional framework for drawing conceptual conclusions from the reviewed clusters.

3. Descriptive Bibliometric Analysis

3.1. Annual Scientific Production and Citations

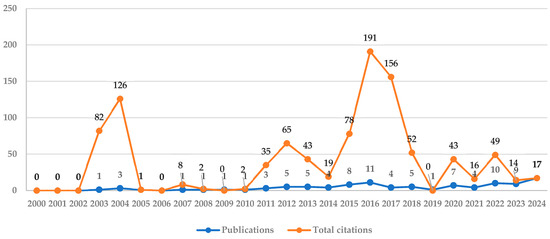

An examination of the annual scientific publications on the financial advisor’s role was considered pertinent to this study. The scholarly output related to this field demonstrated a constant growth trend presented in Figure 5, per year from 2000 to 2024, where the number of publications is represented by the blue line and total citations by the orange line.

Figure 5.

Scientific production and total citations of articles. Source: Data processed by authors.

The overall publication trend shows a gradual increase observed from 2003 onwards, with sporadic fluctuations. The publication rate is relatively low yet stable, from one to 17 publications per year. The number of publications has steadily increased since 2020, with a peak in 2024. suggesting growing scholarly interest in the topic. As highlighted by Sun et al. (2022), the post-pandemic shift towards digital and remote work structures may have increased households’ reliance on financial guidance, possibly contributing to the observed rise in publications since 2020.

Citations show significant fluctuations, with multiple peaks and declines occurring over the years. The first period began in 2002, with a significant increase in citations in 2004 (82 citations), which aligns with early research activity. The peak was reached in 2004 with 126 articles published, after which there was a significant decline. The second ascending phase started in 2014 and peaked at 191 articles in 2016, indicating the impact of key publications. Smaller citation waves emerged after 2019.

A lag is evident between publication output and citation accumulation: citations often peak in the years following publication increases. This may indicate the publication of seminal works or highly relevant studies. Periods of low citation impact despite publications could indicate either less impactful studies or delayed recognition of contributions. The recent rise in publications (2023–2024) suggests an increasing research focus, but its impact remains to be seen in upcoming years through citations. Future research may benefit from analysing citation networks, authorship collaborations, and thematic publication shifts.

3.2. Publications’ Sources

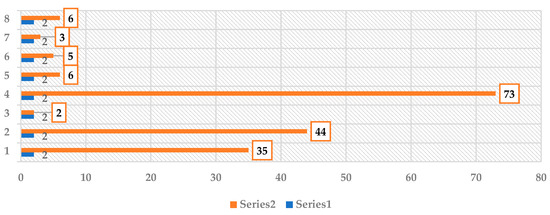

Because sources are also important in publications, Figure 6 presents an analysis of academic sources that have published more than two articles related to the research topic. The graph compares the number of published documents (blue bars) with their respective citation counts (orange bars) in different journals.

Figure 6.

Sources with more than two articles published. Source: Data processed by authors from Biblioshiny.

For instance, Issues in Accounting Education has only two published articles but has accumulated 73 citations, indicating that these publications are highly influential in the academic community. Similarly, Accounting Horizons has two publications and has received 44 citations, emphasising significant research impact. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal has two publications, with 35 citations, suggesting a relatively high citation-to-publication ratio. Other journals, such as Qualitative Research in Accounting and Management and Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies, published six articles each. However, their citation impact is relatively lower, suggesting that their influence is spread across various works while they contribute to the discussion.

Other journals, like the International Journal of Bank Marketing and the Journal of Family Business Management, have two to three publications but lower citation rates (two or three citations each). This may indicate that their articles have not achieved widespread recognition or that the field they contribute to is relatively niche.

To conclude, some sources publish more frequently, while others create a larger impact with fewer publications. This analysis aids researchers in understanding which journals have historically demonstrated the highest impact within the field, thereby informing future publication strategies.

3.3. Countries’ Scientific Production and Citation Analysis

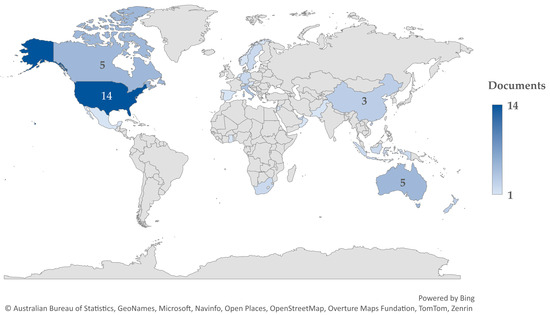

Figure 7 provides a geographical view of research publications related to the study topic, using data processed in MS Excel and customised on a Miller projection world map.

Figure 7.

Countries’ publications world overview. Source: Data processed by authors in MS Excel.

The country-level mapping is based solely on articles where the research output’s origin could be unambiguously extracted through manual screening of author affiliations and metadata fields. It displays the global distribution of publications by country, using shades of blue to indicate the number of documents released. The map shows a regional concentration of research output in North America, Europe, and Australia. While contributions from Asia, Africa, and South America are limited, the presence of research outputs scattered across multiple continents suggests that the topic, although niche, holds global relevance and is gradually attracting international scholarly attention.

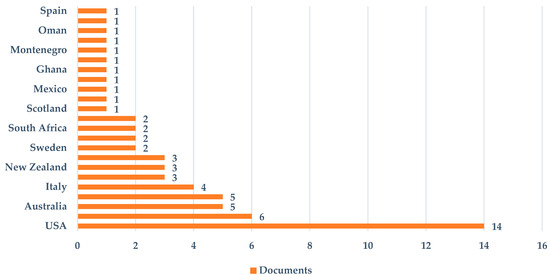

Figure 8 provides a quantitative comparison of publication counts per country within the same context, offering a clearer view of the data.

Figure 8.

Countries’ publications world overview. Source: Data processed by authors in MS Excel.

The USA clearly leads with 14 documents, reflecting its significant influence and active research community. Australia (five documents) and Italy (four documents) maintain substantial contributions, while New Zealand (three documents) and Sweden (two documents) show moderate engagement. The majority of publications originate from developed economies (World Bank, 2024), notably the USA, Australia, and European countries such as Italy and Sweden. In contrast, emerging economies (e.g., Ghana, Mexico, South Africa) are modestly represented, suggesting that while the topic is gaining traction globally, research output remains concentrated in high-income contexts.

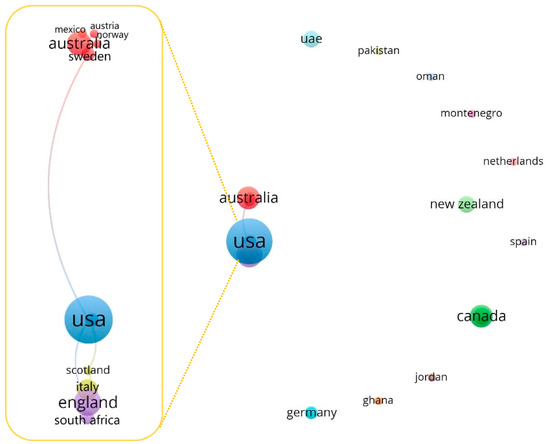

Figure 9, created using the bibliometric tool VOSviewer 1.6.20 (VOS), illustrates the citation links among the countries involved in the research.

Figure 9.

Countries’ citation network. Source: Data processed by authors in VOSviewer.

To explicitly describe the figure, each circle represents a country. The size of the circle indicates the number of documents released. As a threshold, we chose a minimum number of one document released and at least two citations from each country. The USA (14 documents, 194 citations), Canada (5 documents, 306 citations), and England (6 documents, 130 citations) have the most prominent circles, indicating high citation counts and, as a result, being influential in the research. These are all developed countries, reflecting their well-established research infrastructure and financial advisory markets (World Bank, 2024). The following countries, with medium citation values, are Australia (5 documents, 41 citations), New Zealand (3 documents, 54 citations), Scotland (1 document, 33 citations), and Austria (1 document, 27 citations). Despite its lower publication volume, South Africa stands out among the few emerging economies represented due to visible citation linkages. The thickness of the lines reflects the power of the citation relationship. Therefore, the line between the USA, Australia, Scotland, Italy, England, and South Africa is visible in the zoomed-in box, indicating collaboration or mutual influence on the topic researched.

3.4. Author Network and Productivity

The studies from this article encompass diverse geographical contexts such as Australia (Elloy & Smith, 2003), the United Kingdom (Idris & Saridakis, 2018), and Mexico (Castro, 2012), providing a global perspective on the accountants’ role and workplace dynamics.

Table 1 presents the top 10 most cited authors:

Table 1.

Top 10 of the worldwide cited authors.

Leading the ranking, Richins et al. (2017) examine whether big data analytics serves as a disruptive force or a valuable asset for the accounting profession, with their study in the Journal of Information Systems accumulating 131 citations, signalling its significant impact. Similarly, Collins-Dodd et al. (2004) analyse the role of gender in financial performance, a discussion published in the Journal of Small Business Management that has garnered 108 citations, reflecting the enduring relevance of gender-related financial dynamics. In a related domain, Elloy and Smith (2003) explore the intersection of stress, work-family conflict, and role ambiguity among professionals, an article cited 82 times in Cross Cultural Management. Meanwhile, Janvrin et al. (2014) contributed to advancements in data visualisation for accounting, with their work in the Journal of Accounting Education accumulating 77 citations.

To address contemporary professional challenges, Buchheit et al. (2016) provide a comprehensive work-life balance analysis in Accounting Horizons, earning 65 citations. Similarly, Lai (2016) investigates financial ecologies and investment behaviours, as evidenced by their study in Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, which has received 54 citations. Spraakman et al. (2015) examine employers’ expectations regarding IT capabilities among accounting graduates, a paper published in Accounting Education, accumulating 44 citations. Gender roles in high-demand professions are further explored by Castro (2012) in Gender, Work and Organization, where an examination of time pressures and gender expectations in a Big Four firm in Mexico has resulted in 43 citations. Idris and Saridakis (2018) researched how internationalisation impacts small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), with their article cited 39 times being published in the International Business Review. Lastly, Gallhofer et al. (2011) explore work-life preferences and other workplace issues among female chartered accountants in Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal with 33 citations.

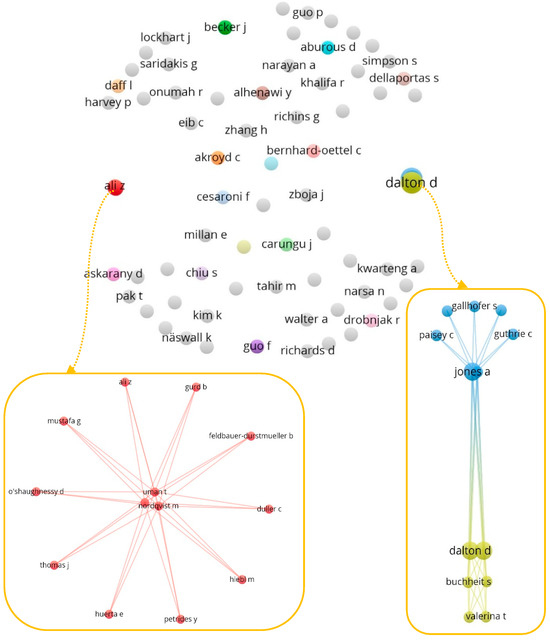

Figure 10 shows the author citation network, highlighting key intellectual contributions on how financial advisors navigate financial and systemic risks in recent years.

Figure 10.

Authors’ citation network. Source: Data processed by authors in VOSviewer.

In VOS, authors were included in this analysis if their research had a minimum of two citations. Among the 127 identified authors, 102 met this threshold. In the resulting network, each node corresponds to an individual researcher. The node size is proportionate to the citation impact, with larger nodes showing more significant academic influence. Citation relationships are represented in the form of connections between nodes. The structure of the network shows clusters that portray the scholars who frequently reference one another. The blue grouping, with Jones at its centre, has strong connections to Gallhofer, Guthrie, and Dalton, signifying an academic community that likely researches social responsibility and ethics in accounting. The red cluster, with Nordqvist M. as a representative figure, demonstrates tight relationships between sustainable financial practices and ethical issues. Looking from a distance, it is noticeable that, however, most of the works are scattered, which may denote multiple subfields of interest in this broad field of study.

3.5. Citations at the Institutions Level

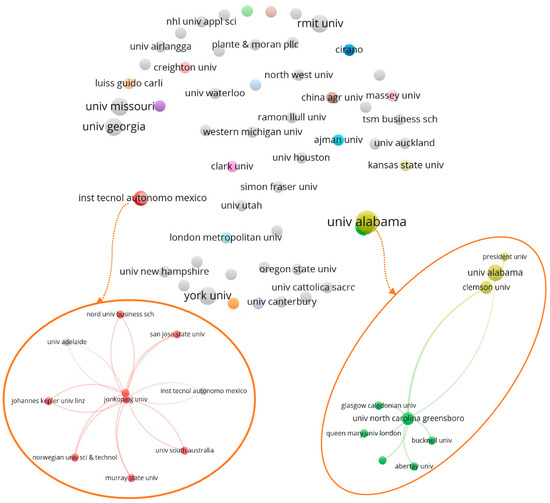

This network visualisation (Figure 11) depicts academic collaborations, showcasing connections between institutions worldwide. To be included in this visualisation, organisations had to meet a minimum threshold of 10 documents and 2 citations.

Figure 11.

Institutions’ citation network. Source: Data processed by authors in VOSviewer.

Among the 93 institutions analysed, 73 fulfilled the specified conditions and are visually depicted within the network. These qualifying universities and associated entities are represented as nodes, whose dimensions may correspond to their level of influence or degree of connectivity. The lines (edges) interlinking these nodes signify academic relationships, such as collaborative authorship or joint research endeavours, with line thickness potentially reflecting the intensity of cooperation. Although no legend is provided, variations in colour could indicate distinct groupings or classifications. Specific connection routes are accentuated through orange circles, notably around Jonkoping University and a grouping that encompasses the University of Alabama, Clemson University, and President University. This visualisation captures the movement of academic engagement, illustrating the ways in which partnerships traverse the network, linking scholars and institutions within an evolving framework of knowledge dissemination.

4. Bibliometric Analyses of the Topics Researched

4.1. Keyword Co-Occurrence Analysis

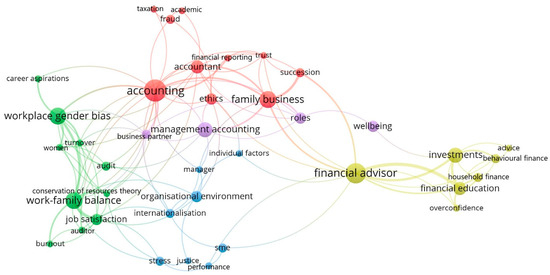

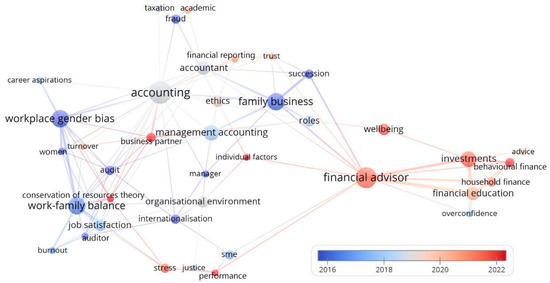

Figure 12 represents a bibliometric network map, constructed through keyword co-occurrence analysis, illustrating the interconnections between key themes in this financial advisory research.

Figure 12.

Keyword co-occurrence cluster. Source: Data processed by authors in VOSviewer.

A minimum of 2 occurrences was set as a threshold for its generation. From 126 keywords, 39 met this threshold. Each node corresponds to a keyword, while the edges signify thematic relationships, with node size reflecting term frequency within the literature. The colour-coded clusters delineate distinct research areas, facilitating the identification of thematic groupings. The five significant clusters encapsulate different domains of inquiry, with central nodes such as “financial advisor” and “accounting” serving as interdisciplinary anchors, linking multiple thematic areas. The network structure reveals strong associations, such as the connection between “ethics” and both “accounting” and “financial advisor”, underscoring the profession’s regulatory and ethical dimensions. Furthermore, terms that have a smaller node like “overconfidence,” “job satisfaction,” and “succession,” reveal specialised subfields that seem to be branching from the primary research themes. This map illustrates both disciplinary concerns and emerging areas of scholarly interest.

This bibliometric visualisation offers a structured yet dynamic view of financial advisory, emphasising its interdisciplinary nature. At the centre of the map, “financial advisor” emerges as a dominant node, closely linked to “investments”, “financial literacy”, and “behavioural finance”. This indicates a shift from traditional accounting duties to broader risk-related roles. The map also highlights “individual factors” as a key element, suggesting that personal traits influence how advisors understand and manage financial risks. Moreover, the visualisation shows connections to regulated fields and new sources of risk, such as financial technology, workplace dynamics, and career sustainability. Overall, the map illustrates the profession’s transformation from a purely technical role to one deeply involved in navigating complex financial and social risks.

Table 2 provides an in-depth analysis of the identified keyword clusters.

Table 2.

Keyword clusters on the topic of research.

Cluster 1 (Red) shows the highest total link strength, followed by Cluster 2 (Green) and Cluster 4 (Yellow). All five clusters demonstrate thematic significance. The main topics were thoughtfully pinpointed based on total link strength to best align with each cluster’s thematic focus. To ensure both analytical clarity and thematic depth, this study presents the discussion of the identified thematic clusters within the Results and Discussion section. This integrated format allows for a simultaneous exposition of findings and their interpretation, facilitating a more coherent link between bibliometric patterns and their conceptual implications. Presenting clusters alongside their critical analysis enables the reader to immediately grasp not only the content of each research stream but also the tensions, contradictions, and research opportunities that emerge from them. This approach is particularly useful in bibliometric reviews, where thematic clustering is not merely descriptive but offers a platform for theoretical reflection and future agenda setting (Donthu et al., 2021).

Building on this foundation, Figure 13 captures how the thematic focus has evolved over time, with a notable shift in recent years from internal business risks to household financial concerns.

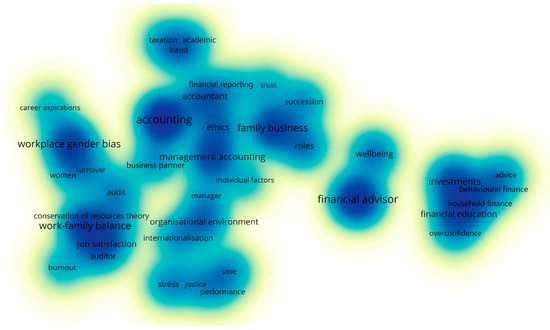

Figure 13.

Keyword co-occurrence overlay cluster. Source: Data processed by authors in VOSviewer.

While not conclusive, this temporal progression offers an early hint of the profession’s ongoing transformation, as financial advisors appear to respond to broader socioeconomic changes and growing household-level vulnerabilities.

In 2016–2018 (blue tones), keywords like “SME”, “family business”, and “management accounting” point to risks tied to internal operations and the accountant’s role in company performance. Between 2018–2020 (grey tones), terms like “accounting” and “accountant” highlight trust and transparency risks in tax and household finance. From 2020–2022 (red tones), the focus moved to “financial advisor”, linked to “household finance”, “investments”, and “financial education”, showing growing attention to managing personal financial risks.

The map also reflects social and career-related risks such as “gender bias”, “burnout”, and “work-family balance”. These changes suggest a shift in the profession: from corporate roles to independent advisory work, raising new challenges around financial resilience and professional sustainability.

The temporal shift toward household finance, literacy, and behavioural themes coheres into an ex-ante orientation of the field (RQ1). This pattern is consistent with M1–M3 becoming central and explains why recent studies emphasize preventive guidance over ex-post correction (RQ2–RQ3).

The following keyword co-occurrence density cluster (Figure 14) reveals a historical shift in the accounting profession: from corporate roles to more personal, advisory ones.

Figure 14.

Keyword co-occurrence density cluster. Source: Data processed by authors in VOSviewer.

Colour intensity (from dark blue to light yellow) shows the frequency and importance of terms. Dense clusters form around “accounting”, “work-family balance”, “workplace gender bias”, “family business”, “financial advisor”, and “financial education”, indicating the traditional accountant’s role. Lighter zones near “investments”, “individual factors”, “advice”, and “well-being” point to newer, independent financial roles. This might reflect a growing trend toward self-employment, where accountants help individuals manage household finances, make investment decisions, and improve financial literacy. Furthermore, we believe that the visual space between these traditional and emerging clusters reflects a growing conceptual distance, but also a potential bridge, between organizational studies and individual financial experiences. Additionally, more isolated terms such as “academic,” “career aspirations,” and “stress” appear to represent niche or developing concerns, possibly pointing to underexplored professional vulnerabilities within the financial advisory field. These findings highlight promising areas for future investigation that may further integrate personal, professional, and systemic dimensions of financial advisory work.

Figure 14 also signals structural change: the move toward self-employment and household-facing work reweights advisory capacity toward individualized, pre-declaration support (M1–M4 along P1–P3). This has two implications: (i) mitigating effects rise where ethics/training are strong; (ii) amplifying risks surface under strain (work–family pressure, corporatization), clarifying when and why findings diverge across contexts (RQ4).

4.2. Preliminary Thematic Mapping: Emerging Clusters and Working Framework

This section introduces the thematic landscape uncovered through keyword co-occurrence analysis. We outline five preliminary clusters identified before full-text review, reflecting term proximity and density rather than final conclusions. These initial groupings, presented in Table 2, serve as analytical anchors for subsequent interpretation.

The clusters are: Accounting and Family Business, rooted in traditional roles; Work–Family Balance and Gender Bias, highlighting professional vulnerabilities; Institutional Frameworks and Personal Dimensions, balancing agency and structure; Financial Advisory and Literacy, reflecting household-facing roles; and Business Partners and Well-being, emphasizing collaboration and relational dynamics.

These themes are interlinked, signaling a profession in transformation. The temporal keyword evolution map (Figure 13) shows a shift from business-centered risks (grey) to household themes (red). The keyword density heatmap (Figure 14) confirms this spatial reorientation, with core terms like accounting contrasting with emergent keywords such as well-being, household finance, and financial education. Together, these patterns suggest diversification and closer alignment with citizen-level risks. While tentative, they provide the framework for the in-depth analysis in Section 4.3, where clusters are revisited through the ex-ante human-interface codebook (M1–M4; P1–P3).

The fluidity of themes offers interpretive richness but also analytical challenges. Articles frequently overlap across two or three clusters, underscoring the field’s interconnectedness and the need to anchor analysis in foundational concepts such as accounting, organizational structures, and institutional frameworks.

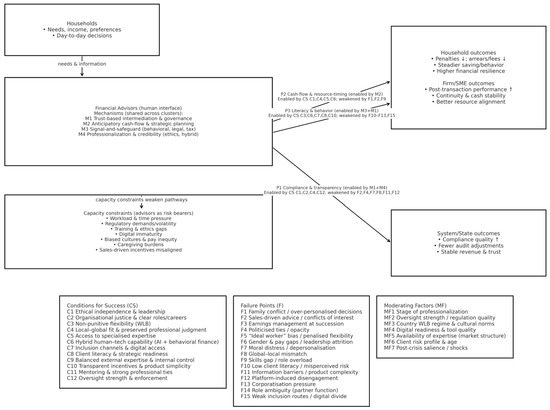

To ensure consistency, we apply a compact human-interface framework across clusters. Four mechanisms recur: M1 (trust-based intermediation), M2 (anticipatory cash-flow planning), M3 (signal-and-safeguard), and M4 (professionalization and credibility). These operate through three pathways: P1 (compliance and transparency), P2 (cash-flow and resource-timing), and P3 (literacy and behavior, including digital trust). Conditions of Success (CS) include ethics, organizational justice, local–global fit, access, digital readiness, and client literacy; Failure Points (F) include family conflict, sales-driven incentives, biased cultures, information barriers, and manipulation at transitions. Moderating Factors (MF) (such as professionalization stage, WLB regimes, oversight strength, and client profiles) explain divergences in outcomes.

Figure 15 illustrates this conditional model: advisors as risk bearers absorb capacity constraints (e.g., workload, regulation, ethics), which weaken M1–M4 and P1–P3, while CS, F, and MF determine whether effects are mitigating (↓) or amplifying (↑) for households, SMEs, and systems.

Figure 15.

Conditional human-interface model. Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

Thus, we propose the following mapping protocol: At the end of each cluster, we (i) identify the dominant mechanism(s) (M1–M4); (ii) indicate the operative pathway(s) (P1–P3); (iii) summarize the net risk implication for households (e.g., mitigating vs. amplifying); and (iv) briefly note any risk-bearer conditions that shape advisory capacity. This protocol preserves thematic nuance while ensuring comparability across clusters. We provide a cross-cluster synthesis at the end of this section.

4.3. Thematic Cluster Analysis

4.3.1. Accounting and Family Businesses (Red)

This cluster anchors the field in its most traditional terrain, where formal accounting meets the family firm and serves as a baseline against which later, more individual-centred themes unfold. At its core lies a relational reading of expertise: advisory quality depends not only on technical mastery but on the advisor’s capacity to translate inherited values into compliant, intergenerational arrangements (Sandgren et al., 2023; Hiebl et al., 2013). In practice, owners tend to prioritise competence over kinship, favouring skilled relatives and sidelining less experienced family members or employees (Huerta et al., 2017). Yet this equilibrium is fragile: unresolved conflicts can hijack the firm when family dynamics collide with financial sustainability (McClendon & Kadis, 2012).

Tension 1: Deep embedding vs. independence risk. A first strand depicts accountants embedded in governance, a configuration associated with superior financial efficiency, risk management, and long-term sustainability in family-influenced SMEs (Sirdar et al., 2024). The challenge, however, is symmetry: the same proximity can morph into over-personalised decision-making and non-optimal risk-taking (Michiels et al., 2021). The literature, therefore, warns that integration, which builds trust, may, without safeguards, compromise independence and objectivity, exposing both firm and profession to credibility risk (Barnes et al., 2024; Lockhart, 2011).

Tension 2: Formalisation and standardisation vs. local practice. A second fault line concerns how formal the controls should be. As family influence wanes, planning typically becomes more formal while trust-based governance persists (Hiebl et al., 2013), with accountants and advisors cast as early custodians of long-term sustainability (Živko et al., 2024). Yet evidence from small farms shows reliance on intuition and informal management accounting, bypassing standardised frameworks (Jakobsen, 2024). The global overlay amplifies the tension: Big Four dominance may prioritise international standards over local advisory needs, limiting access to specialised expertise in places such as the UAE (Khalifa, 2012). The implied lesson is not to reject standards but to maintain local adaptability to avoid rule-context misfit.

Tension 3: Succession as stabiliser vs. site of manipulation. A third axis centres on succession. Mastery of psychological dynamics allows advisors to de-risk transitions and sustain firms across generations (Gurd & Thomas, 2012). Disputes over ownership and control, if unmanaged, produce prolonged legal exposure (Fargher, 2021). The counterpoint is represented by the owners who may manage earnings prior to the transfer to reduce taxes or distort transparency (Kalesnikoff & Hernik, 2019). The same period is also vulnerable to misconduct risks, from valuation ambiguities to unintended fraud or money-laundering exposure, which advisors can help shield against (Wittman & Radakovich, 2009; Ruhl & Wilson, 2008; Wojtyra-Perlejewska & Koładkiewicz, 2024; Shbeilat & Alqatamin, 2022).

Tension 4: Advisory vacuum in banking vs. trust-centred professionals. Historically, banks provided advisory functions, but competitive pressures have recast bank representatives as sales agents, weakening their independence (Takács, 2013). The vacuum invites non-bank professionals to reposition as trusted partners within family firms. This is not entirely new: Renaissance texts portray advisors as guardians of well-being, foregrounding trust, ethical integrity, and long-term alignment with client goals rather than transactional success (Carungu & Molinari, 2022). The juxtaposition underscores an older normative ideal that contemporary practice seeks to operationalise.

Tension 5: Ethics as stabiliser vs. fragility across the life cycle. Ethics emerges as a primary balancing force. Social and academic pressures can rationalise misconduct even before entry into the profession (Nahar, 2018), while ethical sensitivity may decline with age and tenure, suggesting vigilance must be cultivated continuously (Ghosh & Bhuyan, 2024). Political connections can buttress resilience in volatile markets yet simultaneously threaten transparency, a duality acutely visible in family firms (He & Zhang, 2024). Sanctioning misconduct protects clients, but pathways for rehabilitative reintegration remain under-defined (Dellaportas, 2014). Conversely, moral leadership reduces misreporting and strengthens investor trust (Barnes et al., 2024), and organisations with high ethical standards produce more accurate disclosures (Lalevic-Filipovic & Drobnjak, 2017). Regulators thus need to improve prevention and ethical capacity-building (Davies, 2020).

Tension 6: Technology’s promise vs. irreducible human judgment. Finally, technology reconfigures advisory practice. Big data, AI, and blockchain shift attention from routine to risk-aware strategy (Richins et al., 2017; Subramanian & Rahman, 2024). Even so, human judgment remains pivotal for interpreting complex signals and detecting risk (Rishi & Singh, 2011; Rawashdeh, 2024). In education, AI heightens the urgency of ethics training (Maruszewska et al., 2024). FinTech and robo-advisors broaden access, yet personal guidance remains vital under uncertainty (Timmerman, 2022; Davies, 2020). The most credible path is hybrid: technology tempered by human oversight and behavioural sensibility (Kulkarni et al., 2023; Hilary & McLean, 2023). In digital settings, CPA-backed assurance seals signal trust more effectively than non-CPA alternatives (Kim, 2013).

Across these tensions, the cluster depicts family-business advising as a human-within-institutions practice: effective when trust-centred intermediation and anticipatory planning are supported by ethical leadership and context-sensitive use of standards and technology, but vulnerable when proximity, sales logics, or politicised ties erode independence. Thus, we identified the next Mechanisms, Pathways, Conditions for Success, Failure Points, and Moderating Factors (we will address all of these globally as “elements” from now on):

- Mechanisms

M1—Trust-based intermediation and governance mediation (primary): mediating between inherited values, regulatory frameworks, and family goals to secure continuity (Sandgren et al., 2023; Hiebl et al., 2013; Huerta et al., 2017; McClendon & Kadis, 2012).

M2—Anticipatory cash-flow smoothing and strategic planning (primary): formalising planning and budgets to stabilise trajectories as firms mature (Živko et al., 2024; Hiebl et al., 2013).

M4—Professionalization and credibility (primary): ethical leadership, accurate disclosure, regulatory capacity, and credible digital assurance (Barnes et al., 2024; Lalevic-Filipovic & Drobnjak, 2017; Davies, 2020; Kim, 2013).

M3—Signal-and-safeguard (secondary): installing protections during high-stakes transitions (succession, valuation, AML) and alerting to manipulation risks (Wittman & Radakovich, 2009; Ruhl & Wilson, 2008; Wojtyra-Perlejewska & Koładkiewicz, 2024; Shbeilat & Alqatamin, 2022; Kalesnikoff & Hernik, 2019; Fargher, 2021).

- Pathways

P1—Compliance and transparency (dominant): from M1/M4 to better disclosure, fewer misstatements, and credible reporting (Lalevic-Filipovic & Drobnjak, 2017; Barnes et al., 2024; Davies, 2020).

P2—Cash-flow and resource-timing (co-dominant): from M2 to smoother cycles and continuity (Živko et al., 2024; Hiebl et al., 2013).

P3—Literacy and behaviour (as needed): digital and behavioural trust signals (Kim, 2013; Kulkarni et al., 2023; Hilary & McLean, 2023; Timmerman, 2022).

- Conditions for Success (CS)

Ethical independence and moral leadership; regulatory capacity that builds as well as polices ethics (Barnes et al., 2024; Davies, 2020); local–global fit and access to specialised expertise to avoid rule-context frictions (Khalifa, 2012; Hiebl et al., 2013); early and continuous ethics formation (Nahar, 2018; Ghosh & Bhuyan, 2024); hybrid human-tech practice that retains judgment (Richins et al., 2017; Subramanian & Rahman, 2024; Rishi & Singh, 2011; Rawashdeh, 2024; Maruszewska et al., 2024; Timmerman, 2022; Kulkarni et al., 2023; Hilary & McLean, 2023); and credible digital signalling (Kim, 2013).

- Failure Points (F)

Unresolved family conflict and hyper-personalised decision-making (McClendon & Kadis, 2012; Michiels et al., 2021); advisory sales logics (Takács, 2013); limited access to expertise under Big Four dominance (Khalifa, 2012); earnings manipulation at succession (Kalesnikoff & Hernik, 2019); politicised ties and opacity (He & Zhang, 2024); declining ethical sensitivity and ill-defined reintegration after sanction (Ghosh & Bhuyan, 2024; Dellaportas, 2014).

- Moderating Factors (MF)

Degree of embedding in governance (Sirdar et al., 2024; Michiels et al., 2021); stage of firm evolution and balance between trust and formalisation (Hiebl et al., 2013; Živko et al., 2024); market structure (Big Four presence) and jurisdictional access to expertise (Khalifa, 2012); banking advisory withdrawal vs. professional ethos of client guardianship (Takács, 2013; Carungu & Molinari, 2022); and the intensity of digital transformation, which strengthens mitigation only when paired with ethics and human judgment (Richins et al., 2017; Subramanian & Rahman, 2024; Rishi & Singh, 2011; Rawashdeh, 2024; Maruszewska et al., 2024; Timmerman, 2022; Kulkarni et al., 2023; Hilary & McLean, 2023; Kim, 2013).

Under the above CS and favourable MF, the cluster’s combined mechanisms mitigate, thus supporting continuity, reducing errors, and smoothing cash flows. When F dominates, the same interfaces become amplifiers of exposure through independence loss, manipulation at transitions, and misaligned standardisation.

4.3.2. Work-Family Balance and Gender Bias (Green)

After exploring accounting as a profession and its early development, it is important to turn to some of the key risks financial professionals face in their careers: the tension between work and family life and ongoing gender inequalities. At the core of these challenges lies a significant concern: burnout. This keyword appears prominently in the cluster, indicating that burnout could be a pivotal concern in the literature examined. Buchheit et al. (2016) show how public accountants report higher work-family conflict than others in the industry, with burnout being exceptionally high in Big Four firms.

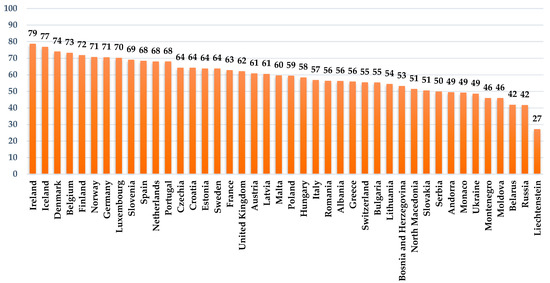

To explore this further, Figure 16 presents recent comparative data on work-life balance across Europe, based on a survey conducted by Remote OK (April–July 2024). This dataset offers a contemporary and geographically diverse complement to the findings of Buchheit et al. (2016), enabling a broader understanding of how work-family tensions manifest beyond the accounting profession alone.

Figure 16.

European work-life balance in 2024, by country (on a scale from 0 to 100). Source: Data processed by authors from dataset retrieved from Statista Research Department (2024).

The results of the study were published by the Statista Research Department on 15 January 2025. The study reveals that the highest score on the work-life balance index was registered in Ireland, with 79 points out of 100. Iceland and Denmark followed, with scores of 77 and 74, respectively, indicating high conditions that balance work and life duties. The countries from the middle of the figure, such as Poland (59 points), Hungary (58 points), and Romania (57 points), have moderate scores, suggesting a more challenging work-life balance compared to the leading regions. Belarus (42 points) and Russia (42 points) indicate significant difficulties in managing work and personal time due to longer working hours and economic pressure. Liechtenstein (27 points) has the lowest work-life balance score, possibly due to its unique working conditions. The work-life balance index assigns a score that evaluates the relationship between work and well-being. It considers factors and policies like legal annual and maternity leaves, healthcare quality, minimum sick pay and wage, LGBTQ+ rights, happiness index scores, and safety standards (Statista Research Department, 2024). The figure highlights how widespread and uneven this risk is. It confirms that beyond organisational factors, personal traits and mental well-being shape how professionals cope with pressure.

Tension 1: Personal resources vs. structural limits. A first line of disagreement concerns the locus of resilience. Psychological resources (self-confidence, optimism, resilience) buffer stress and reduce family conflict (Narsa & Wijayanti, 2021; Laird et al., 2021). Yet dual-career realities frequently outstrip individual coping, especially for women, unless organisations provide active support (Elloy & Smith, 2003, 2004). In other words, personal traits matter but do not suffice without institutional scaffolding.

Tension 2: Flexibility as solution vs. site of bias. Workplace flexibility and clear role definitions are proposed as institutional correctives to stress (Jones & Guthrie, 2016). But over-investment in work, often valorised by professional culture, erodes boundaries and raises psychological risk (Palumbo, 2022). Flexibility itself is gendered: prioritising flexibility can bolster women’s outcomes while lowering men’s profitability, and women are more likely to carry the burden of actively managing WLB (Collins-Dodd et al., 2004). Even where flexibility is nominally offered, ideal-worker expectations persist and penalise those (again, often women) who use it (Jones & Iyer, 2020; Castro, 2012; Gallhofer et al., 2011; Socratous et al., 2016).

Tension 3: Autonomy through self-employment vs. uneven returns. High job demands push auditors to prioritise work over family, reducing satisfaction and raising burnout risk (Yustina & Valerina, 2018). Self-employment promises autonomy, but its benefits are asymmetric: male CPAs report more autonomy and less conflict than women, who face sustained pressures (Prottas, 2012). Thus, the same strategic move can widen gender gaps in well-being.

Tension 4: Retention and ethics vs. attrition under strain. Mentoring, transparent promotion paths, and inclusive leadership improve women’s retention and are associated with stronger ethical attitudes among female accountants (Onumah et al., 2022). Nevertheless, caregiving plus work stress drains resources and has pushed many women out of leadership, accentuated during the COVID-19 crisis (Barnes et al., 2024; Ribeiro et al., 2016). Some professionals do build resilience and remain on track (Laird et al., 2021; Barnes et al., 2024), but without structural and cultural change, gender equity risks being rhetorical (Socratous et al., 2016).

Tension 5: Exemplary careers vs. persistent integration challenge. The biography of Lee Parker illustrates how career rigour coexisted with family prioritisation, reinforcing that work–life integration is a persistent challenge across academia and practice, not a problem solved by seniority alone (Daff, 2022). The lesson is general: professional ambition and personal commitments are co-produced by organisational norms, gendered expectations, and national regimes of support.

Thus, Cluster 2 reframes risk mitigation as human-capacity management. Where organisational design and culture absorb WFC, the advisory function remains reliable; where they do not, availability, quality, and ethical vigilance deteriorate, with gendered consequences that reverberate through firms and client households. Inside this cluster, the following elements were noted:

- Mechanisms

M4—Professionalization and credibility (primary): organisational architecture, flexibility that is not punished, clear roles and career ladders, mentoring and inclusive leadership, all sustain capacity, ethics, and retention; in its absence, burnout erodes professional functioning (Jones & Guthrie, 2016; Onumah et al., 2022; Buchheit et al., 2016).

M1—Trust-based intermediation (indirect): WFC/burnout undercut relationship quality and availability; supportive cultures protect the advisory bond (Buchheit et al., 2016; Onumah et al., 2022).

M2—Anticipatory cash-flow and strategic planning (indirect): preserved human capacity enables forward planning; overload crowds it out (Buchheit et al., 2016; Yustina & Valerina, 2018).

M3—Signal-and-safeguard (indirect): ethical vigilance and behavioural coaching decline with overload and role ambiguity; strengthened under inclusive leadership and career clarity (Jones & Guthrie, 2016; Palumbo, 2022; Onumah et al., 2022).

- Pathways

P1—Compliance and transparency (dominant): institutional containment of WFC preserves task focus and reporting quality; high demands correlate with stress and burnout (Jones & Guthrie, 2016; Yustina & Valerina, 2018; Buchheit et al., 2016).

P3—Literacy and behaviour (co-dominant): gendered behaviours and coping strategies shape interactions and outcomes; flexibility yields asymmetric performance effects (Collins-Dodd et al., 2004; Narsa & Wijayanti, 2021; Laird et al., 2021; Palumbo, 2022).

P2—Cash-flow and resource-timing (indirect only): forward planning depends on available human bandwidth (Buchheit et al., 2016; Yustina & Valerina, 2018).

- Conditions for Success (CS)

Non-punitive flexibility and clear role definitions; transparent promotion paths and inclusive leadership that retains women (Jones & Guthrie, 2016; Onumah et al., 2022). Mentoring and sponsorship to build resilience (Onumah et al., 2022; Laird et al., 2021). Recognition of caregiving burdens and the curbing of overwork norms (Elloy & Smith, 2003, 2004; Palumbo, 2022). Country-level WLB infrastructures (leave, healthcare, safety, rights) supporting capacity (Statista Research Department, 2024).

- Failure Points (F)

Ideal-worker bias and cultures that penalise flexibility (Jones & Iyer, 2020; Castro, 2012; Gallhofer et al., 2011; Socratous et al., 2016). High job demands pushing work ahead of family, stress, burnout, and lower satisfaction (Yustina & Valerina, 2018). Gender/pay gaps and leadership attrition, accentuated in crises (Barnes et al., 2024; Ribeiro et al., 2016; Eib et al., 2015; Ibrahim & Al Marri, 2015). Uneven returns to self-employment by gender (Prottas, 2012). Elevated burnout in Big Four contexts (Buchheit et al., 2016).

- Moderating Factors (MF)

National WLB regimes and policy environments (Statista Research Department, 2024). Gendered preferences and behaviours around flexibility and profitability (Collins-Dodd et al., 2004). Individual psychological resources (Narsa & Wijayanti, 2021; Laird et al., 2021). Organisational role clarity and flexibility design (Jones & Guthrie, 2016). Crisis periods amplifying attrition risks (Ribeiro et al., 2016; Barnes et al., 2024). Biographical and career-stage factors illustrating persistent integration challenges (Daff, 2022).

The cluster’s effect is conditional. Under high strain and biased norms, the system amplifies risk, reducing the quality and availability of advice; when the identified CS are present, the effect turns neutral/mitigating, preserving compliance quality (P1), stabilising advisory behaviour (P3), and indirectly enabling forward planning (P2).

4.3.3. Institutional Frameworks and Personal Dimensions (Blue)

This cluster, as visualised in Figure 14, emerges not as an isolated concern but as an extension of accounting’s traditional subjects. While the previous cluster focused on the personal toll of professional stressors, the current seems to reflect a tighter entanglement between institutional structures and human traits, pointing toward a dual lens of analysis: Institutional Frameworks and Personal Dimensions. This perspective acknowledges that neither individual resilience nor organisational flexibility alone can resolve systemic imbalances such as gendered burnout risk.

In Figure 13, this intersection gains further significance. The current cluster appears to mediate the conceptual shift from Cluster 2 to Cluster 4, a transition that moves through individual traits (factors we classify as personal dimensions). These traits serve as conduits, connecting the lived experiences of professionals to the broader structural logics of their working environments. Thus, the present cluster not only problematises institutional settings but also questions how personal attributes are rewarded, neutralised, or penalised within them.

As shown previously, gendered norms in accounting firms increase emotional risks for advisors. Pressure to meet the ‘ideal worker’ image, along with work-family conflict and biased cultures, causes stress and emotional burnout, especially among women. This can lead to depersonalisation, where professionals lose empathy and see clients as routine tasks. Therefore, the following tensions seem to emerge:

Tension 1: Human strain vs. advisory purpose. Gendered norms in firms (such as pressure to perform as the “ideal worker,” work–family conflict, and biased cultures) induce stress, emotional burnout, and depersonalisation, making work more transactional and less strategic (Bonache, 2022). This undermines the profession’s ambition to move beyond compliance toward high-value advice, and the literature laments the limited global coverage of these human risks (Bonache, 2022).

Tension 2: Global standards vs. local discretion and trust. Internationalisation intensifies pre-existing risks. Resilience and adaptability help professionals meet global client demands (Aburous, 2016), yet the rules that travel do not always land well. Debates around IFRS typically foreground institutional fit, but the on-the-ground effects matter as much: in weakly regulated contexts such as the UAE, foreign frameworks can marginalise local practices, constrain professional discretion, and create frictions between global compliance and local trust-based expectations (Khalifa, 2012). Internationalisation thus reshapes institutional architectures and redefines professional judgment, autonomy, and risk exposure (Khalifa, 2012).

Tension 3: Demand constraints on the client side. Advisory demand is not purely structural: client barriers (limited financial literacy or lack of strategic vision) block effective engagement even when institutional conditions are favourable (Ali & Mustafa, 2023). Institutions shape demand, but individual impediments remain decisive (Ali & Mustafa, 2023).

Tension 4: Triple competency vs. skills gap under digitalisation. As expectations shift from compliance to decision support, professionals face a triple demand: technical competence, strategic insight, and strong client relationships (Spraakman et al., 2015). Put simply, individual adaptability is necessary but insufficient without organisational and educational scaffolding.

Tension 5: Surface flexibility vs. deep career scaffolding. Flexible work policies are often presented as antidotes to stress, yet flexibility without role clarity and transparent career paths fails to relieve anxiety and harms retention (Jones & Guthrie, 2016). The mismatch reveals incomplete organisational design: surface-level accommodation without the deeper supports that make it credible and sustainable (Jones & Guthrie, 2016).

Tension 6: Performance targets vs. ethical integrity. Advisors navigate continuous ethical tension (meeting corporate targets while preserving integrity), leading to emotional exhaustion and moral distress (Ghosh & Bhuyan, 2024). Organisational justice (fair procedures on promotions, workload, recognition) bolsters satisfaction and commitment, while ethical clarity and leadership mitigate pressure (Onumah et al., 2022). Where governance is fragmented or incentives misaligned, trust erodes and professionals detach (Ali & Mustafa, 2023; Barnes et al., 2024).

Based on these outlined literature tensions, this cluster reframes risk mitigation as a two-way conduit between institutional frameworks and personal dimensions. Advisory capacity is a systemic property: when human strain accumulates, its effects radiate outward into client relationships and financial outcomes; when institutions align justice, role clarity, and upskilling with ethical leadership, personal resilience becomes effective rather than compensatory. The following elements were identified:

- Mechanisms

M4—Professionalization and credibility (primary): organisational justice, transparent careers, and ethical leadership preserve commitment and integrity under demanding conditions; they provide the infrastructure that turns flexibility into workable capacity (Jones & Guthrie, 2016; Onumah et al., 2022; Ghosh & Bhuyan, 2024; Barnes et al., 2024).

M1—Trust-based intermediation (primary): depersonalisation and strain reduce relational quality; conversely, fit-for-purpose institutional settings enable trusted, non-transactional advisory (Bonache, 2022).

M3—Signal-and-safeguard (via traits/adaptability): resilience/adaptability supports judgment under global pressure; safeguarding is tested where global–local frictions constrain discretion (Aburous, 2016; Khalifa, 2012).

- Pathways

P1—Compliance and transparency (dominant): under M4 and organisational justice, procedures and oversight enhance commitment and reduce ethical fatigue; where incentives misalign, compliance becomes brittle (Jones & Guthrie, 2016; Ghosh & Bhuyan, 2024; Onumah et al., 2022; Barnes et al., 2024).

P2—Cash-flow and resource-timing (conditional): when timing/design decisions hinge on professional discretion, global–local fit and preserved judgment determine whether planning advice is heeded (Khalifa, 2012).

- Conditions for Success (CS)

Organisational justice with clear roles and transparent careers (Jones & Guthrie, 2016); ethical clarity and leadership (Onumah et al., 2022); incentive alignment that reduces moral distress (Ghosh & Bhuyan, 2024); local regulatory capacity and room for professional discretion under international standards (Khalifa, 2012); continuous upskilling to meet the triple demand (Spraakman et al., 2015); client readiness (literacy/vision) to convert institutional support into actual engagement (Ali & Mustafa, 2023); and resilience/adaptability to operate in global markets without eroding trust (Aburous, 2016).

- Failure Points (F)

Moral distress and depersonalisation under target pressure (Ghosh & Bhuyan, 2024; Bonache, 2022); global–local mismatch that constrains judgment (Khalifa, 2012); skills/analytics gap and role dilution (Spraakman et al., 2015); surface flexibility without career scaffolding (Jones & Guthrie, 2016); low client literacy/vision that blocks engagement (Ali & Mustafa, 2023); and burnout-linked detachment where governance and incentives are fragmented (Barnes et al., 2024).

- Moderating Factors (MF)

Local oversight strength and regulatory capacity (Khalifa, 2012); professional autonomy within international frameworks (Khalifa, 2012); client engagement and literacy (Ali & Mustafa, 2023); technology/analytics readiness (Spraakman et al., 2015); resilience/adaptability in global contexts (Aburous, 2016); and the gendered norms/WLB context connecting back to Cluster 2 (Bonache, 2022; Figure 13).

In conclusion, when adaptability is matched with fit-for-purpose intermediation (justice, role clarity, ethical leadership, discretion under global rules), the effect is mitigating (P1 dominant; P2 when timing/design matters). Where skills gaps, global–local frictions, and ethical fatigue persist, the system amplifies complexity, degrading advisory quality and availability.

4.3.4. Financial Advisory and Literacy (Yellow)

If risk mitigation is understood as a profoundly human process, then the advisor’s role must also be viewed through their capacity to transfer knowledge and build confidence. The following cluster, centred on financial advisory and literacy, brings this perspective into focus. Here, financial professionals are not simple intermediaries, as we aim to uncover how they emerge as educators. The literature ties enhanced literacy to fewer poor decisions, lower vulnerability to shocks, and reduced personal/systemic risk (Timmerman, 2022; Tahir et al., 2022). However, the educator role sits within institutional logics and market infrastructures that can amplify or blunt its effects.

Figure 12 (keywords co-occurrence) underscores investment as a focal terrain where knowledge becomes action: advisors help households navigate risk assessment, retirement planning, and diversification (Jamaludin & Gerrans, 2015; Meyll et al., 2020; Shin et al., 2020).

Tension 1: Education as resilience vs. structural frictions to inclusion. Advisors improve inclusion by connecting marginalised groups to formal finance (Dash & Mohanta, 2024). Yet product complexity and information barriers obstruct uptake (Lai, 2016), and compensation structures may distort priorities toward sales and over-financialisation. The same educational interface can therefore empower or, when incentives are misaligned, expose clients to biased guidance.

Tension 2: Platforms and access vs. erosion of trust bonds. Digitalisation promises scale and efficiency, but platform logics can disrupt the long-term advisor–client bond anchored in trust (Annushkina & Invernizzi, 2018). Advisors must preserve engagement and ethical standards where speed and automation dominate (Timmerman, 2022), or risk hollowing out the very trust that underwrites learning.

Tension 3: High-stakes advisory vs. valuation/forensic risk. Advisory now extends to forensic contexts in family law and business valuation, where advisors influence outcomes in asset division, tax, custody, alimony, and child support (Glenn et al., 2015; Sbarra & Emery, 2013; Quirin & O’Bryan, 2016). The promise is better decisions under pressure; the peril is that poor advice or unclear valuations propagate financial and emotional harm to households.

Tension 4: Advisor as educator vs. advisor as risk bearer. Even in this client-focused cluster, advisors bear risk themselves: specialists require tailored financial planning to align career volatility and long-term stability; for instance, single women in finance in East Asian cities exhibit independence yet need customised wealth strategies (Nakano, 2014). In the public sector, advisors shape budgeting and accountability (Hussein, 2020), but weak ethics and oversight can bend advice toward short-term or personal interests (Hacketha, 2015), undermining public trust.

Tension 5: Technical compliance vs. behavioural decision-making. In crypto-asset taxation, expertise is necessary but insufficient: rules vary by jurisdiction and transaction type (Lazea et al., 2025), and behavioural finance crucially conditions decisions (White & Koonce, 2016; Hilary & McLean, 2023). Regulation cannot eliminate psychological risk (Heo et al., 2024). Behavioural patterns extend to the macro level by shaping aggregate vulnerability in shock-prone regions; thus, improving financial behaviour functions as public risk management (Upreti et al., 2016).

Tension 6: Post-pandemic crises push clients to seek educator–strategist advisors (Alhenawi & Yazdanparast, 2022) and to embrace personalised, behaviourally informed planning (Montmarquette & Viennot-Briot, 2015; Tahir et al., 2022; Meyll et al., 2020). Yet advisors must also self-regulate ethically and emotionally to guide households effectively, especially in family business contexts marked by deep personal involvement (Shin et al., 2020; Collins-Dodd et al., 2004; Huerta et al., 2017). Where advisors act as mediators in succession, they confront behavioural resistance and family tensions (Wojtyra-Perlejewska & Koładkiewicz, 2024); in practice, some contexts (e.g., Italy) show central advisory roles that rarely address intra-family conflict or succession head-on (Cesaroni & Sentuti, 2016). Cultural specificities matter: e.g., Indonesian marriage transactions embed social norms in accounting, complicating standardised approaches (Hermawan & Nomleni, 2024).

Tension 7: Human judgment vs. hybridisation with AI. Human subjectivity can distort recommendations (Davies, 2020), motivating hybrid models that combine AI-driven insights with behavioural finance to reduce conflicts of interest and tailor solutions, especially for digitally literate clients (Kulkarni et al., 2023). The educator role is thus not replaced but augmented by technology; the challenge is aligning tools with ethics.

Across these tensions, the educator–advisor transforms literacy into risk-aware action, from everyday budgeting to complex legal and digital domains. Table 3 captures this role’s breadth and its liabilities: role overload, ethical ambiguity, skill obsolescence, and conflicting demands. The cluster therefore pivots on whether institutional conditions and incentive architectures allow the educator function to operate cleanly.

Table 3.

Financial advisor responsibilities.

Inside this cluster, the following elements were identified:

- Mechanisms

M3—Signal-and-safeguard (primary): diagnostic education + tailored safeguards in legal/forensic, public budgeting, and tech/tax environments; explicitly behaviour-aware advice to reduce penalties, volatility, and missteps (Glenn et al., 2015; Sbarra & Emery, 2013; Quirin & O’Bryan, 2016; Hussein, 2020; Heo et al., 2024; White & Koonce, 2016; Hilary & McLean, 2023).

M1—Trust-based intermediation (secondary): long-term relational credibility that sustains the educator function across entrepreneurial families, estate planning, and culturally embedded negotiations (Gatti, 2005; Kirby, 2004; Hermawan & Nomleni, 2024; Wojtyra-Perlejewska & Koładkiewicz, 2024).

- Pathways

P3—Literacy and behaviour (primary): advisors reduce impulsivity, align risk perceptions, and foster disciplined saving/investing; they build resilience and steady decision-making at the household level (Heo et al., 2024; Montmarquette & Viennot-Briot, 2015; Tahir et al., 2022; Meyll et al., 2020; Alhenawi & Yazdanparast, 2022).

P1—Compliance and inclusion (secondary): through clearer rules translation and independent signalling, especially in digital commerce where small/family firms face online tax, pricing, and payment risks (Zhang et al., 2024); independent, transparent advisors raise literacy over time compared with sales-driven models (Migliavacca, 2020; Dash & Mohanta, 2024).

- Conditions for Success (CS)

Independence and transparency in compensation and oversight to curb product bias (Migliavacca, 2020; Davies, 2020); effective safeguards and clear ethical guidelines, especially in public advice (Hussein, 2020; Hacketha, 2015); tool quality and digital inclusion so hybrid models genuinely help rather than exclude (Kulkarni et al., 2023); behaviourally informed pedagogy aligned to client risk tolerance, age, and experience (Heo et al., 2024; White & Koonce, 2016; Hilary & McLean, 2023); cultural adaptation in family and marital finance (Hermawan & Nomleni, 2024; Wojtyra-Perlejewska & Koładkiewicz, 2024; Gatti, 2005; Kirby, 2004); and targeted inclusion programmes that lower long-term risk in marginalised groups (Kitchen et al., 2022; Sivasankaran & Selvakrishnan, 2023; Kayis-Kumar et al., 2023; Avanesh & Zachariah, 2023; Dash & Mohanta, 2024).

- Failure Points (F)

Sales-biased incentives and over-financialisation (Migliavacca, 2020; Lai, 2016); platform-induced disengagement and erosion of relational trust (Annushkina & Invernizzi, 2018); poor valuation/forensic practice leading to harmful legal outcomes (Glenn et al., 2015; Sbarra & Emery, 2013; Quirin & O’Bryan, 2016); weak ethics/oversight in public settings (Hacketha, 2015); technical-only approaches in tech/tax that ignore behaviour (Heo et al., 2024; White & Koonce, 2016); cultural misfit when Western templates are applied without adaptation (Cesaroni & Sentuti, 2016; Hermawan & Nomleni, 2024).

- Moderating Factors (MF)

Client digital literacy and tool quality (Kulkarni et al., 2023); age and risk profile (Pak & Chatterjee, 2016; Guo et al., 2024); post-crisis salience elevating demand for educator–strategist roles (Alhenawi & Yazdanparast, 2022); institutional ethics and independence safeguards (Davies, 2020; Hussein, 2020); family-business context and cultural norms shaping mediation needs (Shin et al., 2020; Collins-Dodd et al., 2004; Huerta et al., 2017; Wojtyra-Perlejewska & Koładkiewicz, 2024).

With the above CS and favourable MF, the cluster shows a mitigating effect: it closes knowledge gaps, reduces penalties and errors, and steadies household decisions. Where F prevail (biased incentives, weak oversight, platform disengagement, cultural misfit), the same educator interface can amplify risk despite technical competence.

4.3.5. Business Partners and Well-Being (Purple)