Abstract

Are common stocks issued by timberland companies a good investment? Portfolios of large US timberland corporations are compared to simultaneous investments in a diversified US common stock index. Over a 20-year sample period it turns out that the US timberland corporations, on average, perform about as well as the highly diversified US stock market index. It is surprising that the timberland companies do not outperform the stock market indexes because, in order to encourage tree planting, the US Congress has almost completely exempted timberland companies from paying federal income taxes. Furthermore, it is scientifically impossible to assess the value of the large amounts of photosynthesis that the timberland companies produce. As a result of these two ambiguities, it is difficult to state decisively that the timberland companies are better investments than a diversified portfolio of common stocks. However, valuing timberland companies is more practical than endeavoring to value the trees directly.

1. Introduction

This paper analyzes the financial economics of investing in US timberland companies. Markowitz’s Nobel prize-winning portfolio theory is formulated to serve as our decision-making tool.

The US is one of the world’s largest producers of timberland (BizVibe 2020). Previous studies suggested that US timberland investments typically yield good risk-adjusted rates of return (Swensen 2009; Zhang 2021). Unless something unusual happens, US timberland usually appreciates 5 to 10% per year. Growing concern over the world’s environment suggests that carbon capture1 and the increasing growth of the timberland industry2 might provide good paths to improving the earth’s atmosphere.3 For these reasons, the popularity of timberland investing in the US has continued to increase (see National Association of Real Estate Investment Trusts (NAREIT) 2023; Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) n.d.; Swensen 2009).

Timberland attracts buy-and-hold investors. Active traders are not usually attracted to take timberland positions because the timberland prices tend to equal the present value of the future timber harvests. These present values are not highly volatile because both a nation’s tree harvests (the PV numerator) and the appropriate discount rate (in the PV denominator) are not very volatile. The discount rate on future tree harvests changes gradually because it is determined primarily by the market interest rates on long-term bonds, the rate of inflation and Federal Reserve monetary policies that tend to smooth price fluctuations.

Ellefson and Kilgore published an in-depth study of the structure and organization of the timberland industry (Ellefson and Kilgore 2010). Cubbage, Kaniesky, Rubuilar, Bussoni, Olmos, Balmelli, Donagh, Lord, Hernandez; Zhang, et al. expanded the area of inquiry to include global timber investments (Cubbage et al. 2020). Additionally, in 2020, Chuddy and Cubbage suggested timberland be considered to be an asset class (Chuddy and Cubbage 2020). Based on the findings of these previous studies, this paper investigates two decades of US empirical data to analyze investments in timberland companies. Important new financial developments such as real estate investment trusts (REITs), timberland investment management companies (TIMCOs) and related structures are also analyzed (Zhang 2021).

The purpose of this study is to ascertain whether or not US timberland companies are good investments and also, to a limited extent, to assess the impact of the timberland industry on society. Large, diversified portfolios of US timberland companies are studied. This inquiry does not investigate homes, small plots of land and other types of property that are not listed and traded on a stock exchange because these investments are less fungible.

The timberland analyzed here includes growing trees of any size that are suitable to be managed for timber harvesting over a long period of time. The samples include land that may have been naturally or artificially regenerated for recurrent growing and harvesting of marketable trees.4

This introductory section provides background information. Section 2.1 explains the methodology used by the National Council of Real Estate Investment Fiduciaries (NCREIF) to create several different real estate price indexes. NCREIF draws on information from over 12 million acres of private property. Section 2.2 introduces real estate investment trusts (REITs) and discusses the increasingly important role REITs have assumed in the US timberland industry in recent decades. Then, 10 large US wood processing companies that own timberland are introduced. The following sections contrast the profitability of investing in timberland companies with the profitability of investing in a diversified portfolio of US common stocks.

Regression analysis is a statistical tool used in this paper to analyze the empirical timberland returns. Section 3 discusses statistical results. Section 4 introduces portfolio analysis tools—created by Markowitz (1952, 1959), Sharpe (1963, 1964, 1966), and others (Treynor 1965; Treynor and Black 1973)—that are used to rank the desirability of different timberland investments. Section 5 contains four conclusions suggested by this research.

2. Methodology

This section introduces nation-wide sources of timberland data and explains the statistics calculated from these data.

2.1. The National Council of Real Estate Investment Fiduciaries (NCREIF)

NCREIF is a large, well-known organization that collects private data quarterly from every data-providing member, analyzes the data, and publishes reports that are useful to NCREIF members and non-members alike.5 At present, NCREIF requires a minimum of $50 million assets under management (AUM) to become a data-providing member. In its earlier years, NCREIF accepted members with smaller portfolios.

2.1.1. NCREIF Fundamentals

Table 1 summarizes how a few property owners got together in 1987 and formed a non-profit information-sharing organization named NCREIF. Today, NCREIF maintains several different real estate indexes, but we focus on only the timberland index.

Table 1.

Statistics about NCREIF’s Assets Under Management (AUM).

2.1.2. NCREIF’s Timberland Index

The information content in a good market index can help investors make rational investment decisions. The purpose of the NCREIF Timberland Index is to provide information to NCREIF’s data-providing members and its subscribers about the current value of their property holdings. The NCREIF Timberland Index is a market-value-weighted index that is based on appraisals, instead of market determined prices. NCREIF keeps track of the timberland properties owned by its data-providing members. These members are required to maintain up-to-date audited records that use fair market value accounting principles instead of book-value accounting. This information enables NCREIF to publish current information by using the latest information it collects from its data-providing members. Today, NCREIF compiles information from one of the largest timberland portfolios in the US, and one of the oldest.6 However, compared to more recent developments, NCREIF is no longer the most prominent source of information about real estate prices.

2.1.3. Issues with the NCREIF Timberland Index

The remainder of this paper analyzes monthly returns from the University of Chicago’s Center for Research in Security Prizes (CRSP) database. NCREIF data differ from CRSP data in four respects. First, the companies in the CRSP database are all profit-maximizing corporations, while NCREIF is a non-profit organization that surveys only those timberland investors that choose to join NCREIF. Second, the average returns and the variances of returns from the NCREIF index tend to be smaller than similar statistics from the CRSP data. This is because NCREIF uses appraised values. Appraised values vary less than the market-determined CRSP prices.7 Third, anchoring bias causes the returns from the NCREIF appraisals to have smaller standard deviations than standard deviations computed from market-determined returns (Chapman and Johnson 2002; Sherif et al. 1958). Fourth, most of the CRSP returns are from the stocks issued by leveraged corporations. In contrast, the NCREIF returns are either not leveraged, or else they report unleveraged data to NCREIF. Because of these differences, it is not entirely appropriate to compare the returns from the NCREIF index with returns from the CRSP database. A limited amount of NCREIF data is illustrated in Figure 1 below, because the NCREIF price index has been followed by numerous real estate owners and property managers for many years. However, all the returns from the various timberland companies discussed below are market-determined CRSP monthly returns, rather than quarterly appraisal-based returns. The CRSP returns from different investments are more comparable with each other than they are with the unique NCREIF returns.

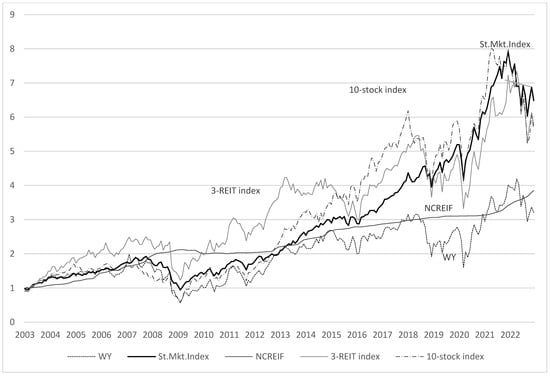

Figure 1.

Illustration of five different investment paths, 2003–2022.

2.2. Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs)

A REIT is like a mutual fund that invests only in real estate. More generally, REITs are companies that own and operate a diversified portfolio of real estate investments that produce rent and other types of income for the REIT owners. In 1960, President Eisenhower signed a law stipulating that US REITs are exempt from federal corporate income taxes. Another law requires every REIT to pay at least 90% of each year’s annual income as cash dividends to its shareholders. All cash dividends a REIT pays to its investors are fully taxable at the ownership level. Instead of being subject to the double taxation that most US corporations face, REIT investors’ income is hardly taxed at all at the federal level. The tax-exemption that REITs enjoy at the corporate level is sufficient to motivate some timber companies to reorganize to become a REIT.8 Making timberland REITs largely exempt from federal income taxes also helps stimulate their growth.

2.2.1. The Structure of REITs

REITs offer investors both portfolio diversification and a large amount of federal income tax-exemption. In order to gain tax exemption from US federal income taxes, a REIT must comply with the following provisions in the US Internal Revenue Service (IRS) code.

- Derive at least 75% of the REIT’s gross income from real estate rent, from interest on mortgages that finance real estate, or from their real estate transactions;

- At least 75% of the REIT’s total assets must be invested in real estate, cash, or US Treasury securities;

- Pay out to the REIT shareholders every year at least 90% of the REIT’s income in the form of cash dividends that are subject to income taxes;9

- Be managed by a board of directors or trustees;

- Be a company that is organized and taxed as a corporation;

- Have at least 100 shareholders after the first year of existence;

- Have no more than 50% of its shares held by five or fewer shareholders.

2.2.2. Three Timberland REITs

Table 2 lists three large US timberland REITs. These large REITs also manage additional acreage owned by other REITs and/or non-REITs, and they receive fee income for their managerial services.

Table 2.

The three largest publicly traded timberland REITs.

Weyerhaeuser is the largest private timberland owner in the US.10 In order to reduce its federal income taxes substantially, in 2016 Weyerhaeuser took one of several major steps to transform the company into more of a pure play timberland REIT. In 2016, Weyerhaeuser sold its cellulose fibers division to the International Paper Corporation for $2.2 billion (Smith 2016). More specifically, Weyerhaeuser sold seven factories that produce fiber, which is used to make products such as paper, diapers, and tissues. This sale helped Weyerhaeuser conform with the IRS requirements to become a tax-exempt REIT.

2.2.3. Tree Care

Every business needs to be profitable to survive. But the profit motive does not seem to stop many timberland owners from spending large amounts on activities to enhance the environment. Some policies of the Weyerhaeuser Corporation, for example, are discussed below because Weyerhaeuser makes more information available to the public than other timberland investors.

- Weyerhaeuser is a dues-paying member of the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), the Sustainable Forestry Initiative (SFI), and some similar trade groups.11 The FSC is an international non-profit organization that promotes responsible management of the world’s forests via timber certification. This organization uses a market-based approach to implement its international environmental policies. In contrast, the SFI is a sustainability organization operating in the US and Canada that works in four directions: set standards, conservation, community relations, and education. SFI also operates two youth education initiatives, named Project Learning Tree and Project Learning Tree Canada. Weyerhaeuser certifies that 100% of its timberlands and wood products conform to SFI standards.12

- Carbon is one the main ingredients in tree trunks, branches, roots, and leaves. Weyerhaeuser estimates that its trees remove the equivalent of 32 million metric tons of carbon dioxide per year from the world’s atmosphere. Stated differently, Weyerhaeuser estimates that its timberlands provide atmospheric benefits equivalent to taking 7 million automobiles off the US roads every year.

- Weyerhaeuser estimates that its trees remove more than four times the amount of carbon dioxide that its aggregate corporate operations create and emit each year. This makes the Weyerhaeuser Corporation a consistent major net negative carbon citizen.

- When Weyerhaeuser reforests its land, it follows good forestry guidelines to maximize the growth and sustainability of the new forest.

- Weyerhaeuser does not harvest the trees growing along the edges of its lakes and streams because these are areas where wildlife is most active.

- Weyerhaeuser publicly sells permits to camp, hunt, and fish on most of its land.

- Weyerhaeuser plants between 130–150 million tree seedlings each year.

- Weyerhaeuser harvests only about 2% of its 10–12 million acres of timberlands each year, and most of the harvested acreage is reforested within one year. Weyerhaeuser owns virtually no barren land.

Many small-scale tree farmers and individual loggers are less conscientious than the Weyerhaeuser Corporation. However, conversations with them reveal that they too have some affection for their trees.

2.2.4. Significant Characteristics of REITs

The first noteworthy characteristic of timberland REITs is the size of their timberland holdings. Each of the three REITs listed in Table 2 is large enough to give them access to economies of scale unavailable to most lumber companies. Two additional advantages are also noteworthy.

Second, REITs’ almost total (as much as 90%) exemption from corporate income tax has a tax advantage over non-REIT investments, which are subject to double taxation at both the corporate level and at the investor level. If everything else is equal, double taxation makes investments in non-REITs less attractive than investing in REITs.

Third, timberland REITs produce more lumber and the associated photosynthesis than other companies simply because the REITs own more timberland. For example, in its company literature, Weyerhaeuser explicitly discusses the fact that its large timberland holdings and the accompanying production of photosynthesis improve the quality of life for every mammal on earth by improving the atmosphere. Other timberland REITs rarely, if ever, discuss photosynthesis.13

2.2.5. Trends in the Timberland Industry

During the 1950s, most US timberland was owned by government agencies, private wood processing companies and nonindustrial private forest owners. Some private owners formed master limited partnerships (MLPs) to hold their timberland. During the 1980s the early timberland investment management companies (TIMOs) began buying small private plots of timberland and thereby inserting some distance between the blue-collar loggers and the white-collar investment managers. During the 1990s, REITs begin buying up the existing timberland MLPs to further separate the loggers from the investors. During the following decades, these trends accelerated and have institutionalized a white-collar timberland management industry.

REITs and timberland investment management companies (TIMOs) differ in a number of respects. Nevertheless, they are still similar institutional timberland investment management arrangements that have both grown rapidly for decades as they competed to take over the US timberland industry.14 The growth of REITs and TIMOs is probably what enables the US to produce and export more timber than Russia, even though Russia has more forest land than the US (BizVibe 2020).

2.3. Empirical Statistics from the Timberland Returns

The total rate of return from a timberland company is denoted . These holding period returns include any gain or loss from a change in the investment’s market price, plus any cash flow income earned during that holding period (such as cash dividends, rental income, or interest income), all divided by the purchase price at the beginning of the holding period, as shown in Equation (1).

An investment’s excess return equals the total return in Equation (1) minus a simultaneous riskless interest rate. Monthly returns from the 30-day US Treasury bill were used to compute the excess returns, denoted in Equation (2).

Except for NCREIF data, all the rate of return statistics starting from Table 3 were calculated from monthly total returns obtained from the University of Chicago’s Center for Research in Security Price’s (CRSP’s) database.

Table 3.

Statistics from common stock and timberland investments, January 2003–December 2022.

Regression Equation (3) defines William Sharpe’s (1963, 1964) single-index market model.

The excess monthly returns from asset i, denoted x, are regressed onto the excess returns of a highly diversified stock market index, denoted , over t = 1, 2, … 240 consecutive months. The highly diversified stock market index is created and publicized by Roger Ibbotson in Stocks, Bonds, Bills, And Inflation, 2023; new editions are published annually (Ibbotson 2023). Table 3 contains summary statistics. The information in Table 3 is compared to similar statistics from a diversified US stock market index below, after another important segment of the timberland industry is introduced.

2.4. The Wood Processing Industry

Wood processing companies buy timber and also raise some of the timber they use. This timber is used to manufacture lumber, homes, furniture, paper, and other wood byproducts.

Table 4 and Table 5 display information about 10 publicly listed and traded companies that process wood and wood products. Each of these 10 large corporations employs thousands of workers and sells their products to the public and other firms.

Table 4.

Ten wood processing companies, January 2003–December 2022.

Table 5.

Statistics from the ten wood processing companies, January 2003–December 2022.

3. Results

Figure 1 compares the time-paths from various timberland investments with the results from Ibbotson’s market-value-weighted US stock market index.16 Ignoring the returns from the smoothed NCREIF index and the Weyerhaeuser Corporation, Figure 1 shows that the returns from the 3-REIT portfolio and the 10-stock portfolio tend to follow the returns from the Ibbotson stock market index.

3.1. The Returns from Weyerhaeuser and NCREIF

Figure 1 shows that, from 2003 to 2022, Weyerhaeuser had some good years that enabled it to earn a respectable annual average total rate of return of 10.89% over the two-decade sample period, while NCREIF earned a more modest average return of 7.01%. However, Weyerhaeuser’s returns dipped below NCREIF’s returns in a few years. Over the 20-year sample period, the Ibbotson stock market index and the other two timberland indexes usually earned higher returns than Weyerhaeuser, particularly during the sample period’s second decade.

3.2. Comparing Average Returns

Table 3 displays a 20-year average annual total return of 12.39% from the portfolio of 10 equally weighted wood processing companies analyzed in Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5. On average, this is (12.39% less 10.99% equals) 124 basis points of total return per year more than investing in the Ibbotson stock market index. In other words, the wood processing industry sometimes offers higher investment returns than the majority of US stocks.

The 10 wood processing companies tend to specialize in some activity in which they have developed a differential advantage. Even though the REITs own much more timberland, enjoy a legislated income tax advantage, and create substantially more lumber and photosynthesis, the sample of ten non-REIT wood processing companies earned an average rate of return that is (12.39% less 12.23% equals) 16 basis points above the 3-REIT portfolio’s total return per year.17

The findings discussed above might result from data that are too noisy to reveal clearly a significant relationship that might exist, or because of offsetting equilibrium effects on forestry returns.

4. Discussion of Portfolio Performance Theories

William Sharpe (1966) and Jack Treynor (1965) developed well-known portfolio performance evaluation models that consider both an investment’s risk and return simultaneously. Each model creates a single number for each investment that can be used to rank the desirability of different investments. Numerical values for these ratios are shown for the portfolios, in the bottom lines of Table 3. Values for these ratios are not shown for the individual stocks in Table 5 because the Sharpe ratio is inappropriate for analyzing individual stocks (Treynor and Black 1973).

4.1. The Sharpe Ratio and Treynor Ratios (Treynor 1965)

Nobel Laureate, William Sharpe (1966), extended a linear risk-return model developed by James Tobin (1958), an earlier Nobel Laureate (Tobin 1958). The Sharpe ratio is used to compare, contrast, and rank the performance of different investment portfolios (Sharpe 1964, 1966; Sherif et al. 1958). Equation (4) defines the Sharpe ratio, , for investment i.

After dropping NCREIF from further consideration, for the reasons discussed above in Section 2.1.3, the Ibbotson stock market index, subscript S, has the highest Sharpe ratio () in Table 3. The 3-REIT portfolio (), has the second highest Sharpe ratio, and the 10-stock portfolio () is third: . The Treynor ratio yields slightly different rankings.

Equation (5) defines the Treynor ratio, denoted , for the performance evaluation of portfolio p.

By a narrow margin, the Treynor model ranks the 3-REIT portfolio R, denoted , to be the most desirable risk-adjusted return, .

4.2. Discussion of Markowitz Portfolio Theory

Harry Markowitz’s pioneering research introduced the efficient frontier (Markowitz 1952, 1959). The efficient frontier is a collection of portfolios that offer the lowest possible risk for any given level of expected return. When a new asset enhances diversification for investors, it extends the efficient frontier. This means that investors can create portfolios incorporating the new asset, resulting in lower risk for a specified level of expected return.

First, we utilized the Fama-French equal-weighted five-industry portfolios18 as the foundational assets to construct an efficient frontier. Next, we augmented this initial efficient frontier by incorporating the 3-REIT portfolio from Table 3 and the 10-stock portfolio comprising 10 wood processing companies listed in Table 5 This process allowed us to compute a second efficient frontier that encompasses, not only the five industry portfolios but also these two timberland investments.

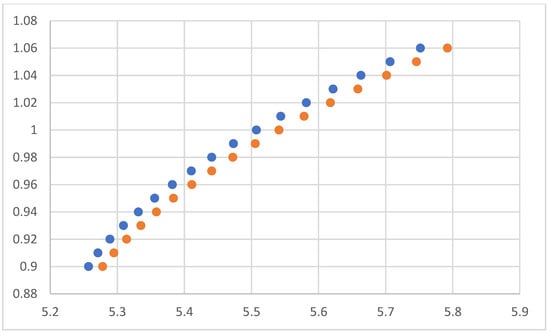

The vertical axis in Figure 2 represents the average monthly excess returns, while the horizontal axis displays the standard deviations of the portfolios’ monthly returns. The lower efficient frontier, indicated by orange dots, illustrates the risk and return metrics of efficient portfolios derived from the five Fama-French industry indexes. Meanwhile, the more favorable efficient frontier, depicted by blue dots, shows the risk and return statistics from the seven investments. These more favorable portfolios include the initial five Fama-French industry efficient portfolios along with two additional US timberland portfolios. Figure 2 illustrates that the inclusion of these timberland investments results in an expansion of the efficient frontier. In other words, for the same level of portfolio mean return, the efficient portfolio incorporating the timberland portfolios exhibits lower risk compared to the efficient frontier without them. The risk reduction is tangible. For instance, at an expected 1% monthly return, the standard deviation of the efficient portfolio constructed from the five Fama-French industry portfolios alone is 5.55%. In contrast, the standard deviation of the efficient portfolio incorporating the two timberland portfolios alongside the industry portfolios is lower at 5.5%. This translates to a 1% decrease in risk, which highlights the risk mitigation achieved by adding the timberland investments to the portfolio.

Figure 2.

Comparison of two Markowitz efficient frontiers. The orange dots illustrate the risk and return metrics of efficient portfolios derived from the five Fama-French industry portfolios. The blue dots show the risk and return metrics of efficient portfolios from the initial five Fama-French industry portfolios plus two additional US timberland portfolios.

5. Four Conclusions

Several conclusions can be drawn from the preceding research.

5.1. Inflation Hedging

The consumers price index (CPI) rose at an arithmetic average rate of 2.55% per year from 2003 through 2022. Table 3 shows that the NCREIF index earned an average rate of return of 7.01% per year; the 10-stock portfolio of wood processing companies generated an arithmetic average return of 12.40%, which is slightly above the 3-REIT portfolio’s 12.24% average return, and also above the stock market index portfolio’s average return of 10.99%. It is apparent that the timberland investments are all excellent inflation hedges.

5.2. Investment Rankings

The Ibbotson stock market index had the highest Sharpe ratio in Table 3 (Sharpe 1966). According to the Treynor measure (Treynor 1965) the 3-REIT portfolio had the highest risk-adjusted return. The 10-stock portfolio’s 12.40% average return and the 3-REIT portfolio’s 12.24% average return are both slightly above the arithmetic average return from the Ibbotson stock market index. But neither of the timberland portfolios have performance rankings that are consistently superior by all of the appropriate investment performance measures. These various considerations suggest that US timberland investments tend to perform slightly better than an investment in a mutual fund indexed to the Ibbotson stock market index. In other words, timberland investments tend to perform better than the average NYSE-listed common stock or mutual fund.

5.3. Photosynthesis

News sources sometimes report excessive carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Some of these reports describe harmful effects to the world’s environment. These reports often attribute the negative effects to climate change or global warming (Walker et al. 2021). In contrast to these negative issues, this study shows that the Weyerhaeuser, Rayonier, and PotLatchDeltic REITs, for example, each manufacture large amounts of lumber every year. According to their annual reports, during the lumber production process, they also: (i) take many tons of harmful carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere; (ii) produce huge amounts of photosynthesis; and (iii) since photosynthesis produces new oxygen, they also create substantial amounts of new oxygen. These positive findings, to some extent, offset some of the negative discussions of climate change.

As far as we can tell, the production of photosynthesis and the associated new oxygen can only be observed and measured in laboratory experiments. Large amounts of photosynthesis cannot be captured or sold. However, it is plausible that the photosynthesis that is produced by growing trees (or any green plant) is more valuable than the lumber that is produced. Unfortunately, photosynthesis and the new oxygen that it produced is given away for free, because significant quantities cannot presently be captured and sold.

Some production details suggest that the US is capable of producing additional beneficial results. The Weyerhaeuser Corporation’s annual reports and website both state that each year the company harvests only about 2% of its 10–12 million acres of timberland. This suggests that Weyerhaeuser, and perhaps the entire timber industry, might be producing significantly fewer trees than is possible. One important factor that keeps the US timberland industry from increasing its output is inadequate economic incentives. These inadequate incentives were previously reduced in the US by the creation of the tax-reduced REIT structure. Creation of additional incentives is discussed below.

5.4. Increasing the Incentives to Plant Trees

The Real Estate Investment Trust (REIT) Act of 1960 and the Real Estate Investment Trust Simplification Act (REITSA) of 1997 provided income tax exemptions designed to motivate people to create more timberland REITs.19 Simply increasing the size of the REIT tax exemptions would increase the economic incentives to produce more lumber in the US. Stated differently, the existing REIT law could be modified slightly to give the US lumber industry more incentive to produce larger amounts of lumber, and that would also increase the incentive to produce more photosynthesis and more new oxygen. These changes would make the world a significantly healthier and more attractive place to live.

Author Contributions

Formal analysis, J.C.F.; Writing—original draft, J.C.F.; Writing—review & editing, G.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | In 2022 the Weyerhaeuser Corporation and the Occidental Petroleum Corporation (OXY) signed a lease agreement for 30,000 acres of subsurface pore space that Weyerhaeuser controls. These acres will be used to develop a carbon capture and sequestration project designed to reduce the amount of carbon dioxide released into the world’s atmosphere (Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) n.d.). |

| 2 | Photosynthesis is an important chemical process discovered by a medical doctor named Jan Ingenhousz in 1779 (Ingenhousz 1779). Photosynthesis occurs as every green tree, blade of grass, or other green plant absorbs carbon dioxide and creates new oxygen in order to sustain itself. |

| 3 | For a scientific discussion about the harmful effects of climate change see (Walker et al. 2021). |

| 4 | In 2009 the US Forest Service classified 22% of the US as timberland, or land capable of producing industrial wood. David Swensen, (Swensen 2009, pp. 215–16). In 2023, the US federal government owned 238 million acres (31%) of US forests, most of which are managed by the US Forest Service (FS) as part of the National Forest System (NFS) and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). |

| 5 | Information about individual NCREIF members is not disclosed, only NCREIF’s aggregate portfolio statistics are published. |

| 6 | The NCREIF Timberland Price Index was developed when Hancock Timber Resource Group (HTRG), Forest Investment Associates (FIA), PruTimber, the Frank Russell Company, and NCREIF teamed up to develop it in 1992. |

| 7 | For more detail about the statistical issues in appraisal-based data see the discussion of Exhibits 4–9 in (Francis and Ibbotson 2009). |

| 8 | Two types of REITs exist. First, US law permits an equity REIT to own and rent homes, office buildings, timberlands, shopping centers, and other physical real estate. Second, the REIT Act of 1960 defines mortgage REITs that are only permitted to buy mortgage loans that have real estate as collateral, collect interest income from mortgages, and buy and sell mortgages. Mortgage REITs are not discussed further because they do not own any timberland. Mortgage REITs comprise only a small part of the total REIT market. In 2021, NAREIT.com estimated that only about 6% of all outstanding REITs were mortgage REITs. |

| 9 | At the corporate level, US tax law requires that at least 90% of every REIT’s income must be paid out as tax-exempt cash dividends, but this tax-exempt cash dividend income is 100% taxable income at the share-holder level. Portfolios of tax-deferred pension funds and tax-exempt portfolios owned by tax-exempt charitable institutions would benefit little, or not all, from the tax savings granted to REIT investors. |

| 10 | J.D. Irving, Sierra Pacific Industries [the Emmerson Family], Green Diamond Resource Company [the Reed Family] and Peter Buck are large private owners of US timberland. None own as many acres of timberland as Weyerhaeuser. |

| 11 | See Gutierrez Garzon et al. (2020). https://open.fsc.org/handle/resource/917 (accessed on 21 May 2024). |

| 12 | The FSC, SFI, and good forestry cannot totally eliminate all the harm that might be done by foresters. Working a forest will disrupt the lives of fish, fungi, insects, birds, and other forms of forest life in many subtle but long-lasting ways that are not easy to measure. |

| 13 | For unknown reasons, most timberland REITs have not aggressively endeavored to profit from selling carbon credits. Their managers may prefer to avoid the fraud and greenwashing that sometimes occurs in the carbon credit industry (National Association of Real Estate Investment Trusts (NAREIT) 2023). See: https://www.agriinvestor.com/carbon-credits-are-changing-timberland-ownership-and-investment-models-manulife/ (accessed on 21 May 2024). |

| 14 | For a detailed and informative scholarly discussion of REITs and TIMOs, see Daowei Zhang’s 2021 book entitled From Backwoods to Boardrooms: The Rise of Institutional Investment in Timberland (Zhang 2021). |

| 15 | CatchMark Timber Trust (CTT) is a large REIT that was not included in the index because it is significantly newer than the three REITs we chose to study. Including CTT in Table 2 and Table 3 and the REIT index would have shortened the duration of the sample used to compute the statistics in Table 2. Furthermore, in 2022 PotlatchDeltic merged with CatchMark Timber Trust, Inc. in an all-stock transaction that created an integrated timber REIT. Transactions like this are too complicated to include in our study. |

| 16 | |

| 17 | Some results in Figure 1 seem to conflict with the results in Table 3. Figure 1 shows that over the 20-year sample the highly diversified stock market index finished slightly above both the 10-stock wood processors’ portfolio and the 3-REIT portfolio. These results conflict with the rankings of the arithmetic average total returns shown in Table 3, because Figure 1 is based on compounded (geometric mean) returns, while Table 3 contains arithmetic average returns. This apparent conflict is not an error, but provides one more example of a well-known statistical phenomenon. The arithmetic average of a series of numbers exceeds the geometric mean of that series by a difference that increases with the variance of the numbers in the series (Young and Trent 1969). |

| 18 | The data are available from Professor French’s website: https://mba.Tuck.Dartmouth.edu/pages/faculty/Ken.French/data_library.html (accessed on 21 May 2024). (Fama and French n.d.). |

| 19 | More saplings are planted in the US every year. Unfortunately, forest fires and other man-made activities destroy more trees than are planted in the US almost every year. In fact, the net number of standing trees in the world is continually decreasing (World Resources Institute 2024). |

References

- BizVibe. 2020. Global Timber and Wood Products Industry Fact Sheet 2020. March 13. Available online: https://blog.bizvibe.com/blog/largest-wood-producing-countries (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- Chapman, Gretchen B., and Eric J. Johnson. 2002. Incorporating the Irrelevant: Anchors in Judgments of Belief and Value. In Heuristics and Biases: The Psychology of Intuitive Judgment. Edited by Thomas Gilovich, Dale Griffin and Daniel Kahneman. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuddy, Rafal P., and Frederick W. Cubbage. 2020. Research trends. Forest investments as a financial asset class. Foreign Policy Economics 119: 102273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cubbage, Frederick, Bruno Kanieski, Rafael Rubilar, Adriana Bussoni, Virginia Morales Olmos, Gustavo Balmelli, Patricio Mac Donagh, Roger Lord, Carmelo Hernández, Pu Zhang, and et al. 2020. Global timber investments, 2005 to 2017. Foreign Policy Economics 112: 102082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellefson, Paul V., and Michael A. Kilgore. 2010. United States Wood-Based Industry: A Review of Structure and Organization. Staff Paper Series Number 206. St. Paul: Department of Forest Resources, University of Minnesota and Department of Forest Resources, University of Minnesota. Available online: https://conservancy.umn.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/17c34186-a125-4203-ac64-be6de66be348/content (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- Fama, Eugene, and Kenneth French. n.d. Website at Dartmouth University. Available online: https://mba.Tuck.Dartmouth.edu/pages/faculty/Ken.French/data_library.html (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- Francis, Jack C., and Roger G. Ibbotson. 2009. Contrasting Real Estate with Comparable Investments, 1978 to 2008. Journal of Portfolio Management 36: 141–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez Garzon, Alba Rocio, Pete Bettinger, Jacek Siry, Jesse Abrams, Chris V. Cieszewski, Kevin Boston, Bin Mei, Hayati Zengin, and Ahmet Yesil. 2020. A Comparative Analysis of Five Forest Certification Programs. Forests 11: 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibbotson, Roger G. 2023. Stocks, Bonds, Bills, And Inflation. New York: CFA Institute Research Foundation Books. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingenhousz, Jan. 1779. Experiments upon Vegetables, Discovering Their Great Power of Purifying the Common Air in Sunshine, and of Injuring It in the Shade and at Night; Washington, DC: Library of Congress. Available online: https://www.loc.gov/item/18000763/ (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- Markowitz, Harry. 1952. Portfolio Selection. Journal of Finance 7: 77–91. [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz, Harry. 1959. Portfolio Selection: Efficient Diversification of Investments. New York: John Wiley and Sons Inc. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1bh4c8h (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- National Association of Real Estate Investment Trusts (NAREIT). 2023. Organization’s Website. Available online: https://www.reit.com/nareit (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). n.d. Use EDGAR Software to Find Numerous REIT Filings. Washington, DC: Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

- Sharpe, William F. 1963. A Simplified Model for Portfolio Analysis. Management Science 9: 277–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, William F. 1964. Capital Asset Prices. Journal of Finance 19: 425–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, William F. 1966. Mutual fund performance. Journal of Business 39: 119–38. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2351741 (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- Sherif, Muzafer, Daniel Taub, and Carl I. Hovland. 1958. Assimilation and contrast effects of anchoring stimuli on judgments. Journal of Experimental Psychology 55: 150–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, Rich. 2016. International Paper Buys Weyerhaeuser, But Not All of It. The Motley Fool. May 9. Available online: https://www.fool.com/investing/general/2016/05/09/international-paper-buys-weyerhauser-but-not-all-o.aspx (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- Swensen, David F. 2009. Pioneering Portfolio Management. New York: Free Press. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/49732730/Pioneering_Portfolio_Management_2009_ (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- Tobin, J. 1958. Liquidity preference as behavior toward risk. The Review of Economic Studies 25: 65–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treynor, Jack L. 1965. How to Rate Management of Investment Funds. Harvard Business Review 43: 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treynor, Jack, and Fischer Black. 1973. How to Use Security Analysis to Improve Portfolio Selection. Journal of Business 46: 66–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, Anthony P., Martin G. De Kauwe, Ana Bastos, Soumaya Belmecheri, Katerina Georgiou, Ralph F. Keeling, Sean M. McMahon, Belinda E. Medlyn, David J. P. Moore, Richard J. Norby, and et al. 2021. Integrating the evidence for a terrestrial carbon sink caused by increasing atmospheric CO2. New Phytologist 229: 2413–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Resources Institute. 2024. Forest Loss Leader. Global Forest Review, April 4. [Google Scholar]

- Young, William E., and Robert H. Trent. 1969. Geometric mean approximations of individual security and portfolio performance. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 4: 179–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Daowei. 2021. From Backwoods to Boardrooms: The Rise of Institutional Investment in Timberland. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).