Determinants of Sustainable Entrepreneurship in Morocco: The Role of Entrepreneurial Orientation, Financial Literacy, and Inclusion

Abstract

1. Introduction

- -

- To what extent does financial inclusivity influence the sustainability of Moroccan entrepreneurs?

- -

- What role does financial inclusion serve in facilitating access to financial resources and/or services?

- -

- How does financial literacy impact entrepreneurs to sustain their entrepreneurship?

- -

- In what ways does financial literacy affect entrepreneurial performance?

- -

- How does financial literacy mediate the nexus between financial inclusion and sustainable entrepreneurship?

- -

- To what degree does being entrepreneurially oriented impact entrepreneurs’ sustainability?

- -

- How does entrepreneurial orientation interact with financial inclusion to influence sustainable entrepreneurship?

2. Framework and Hypotheses

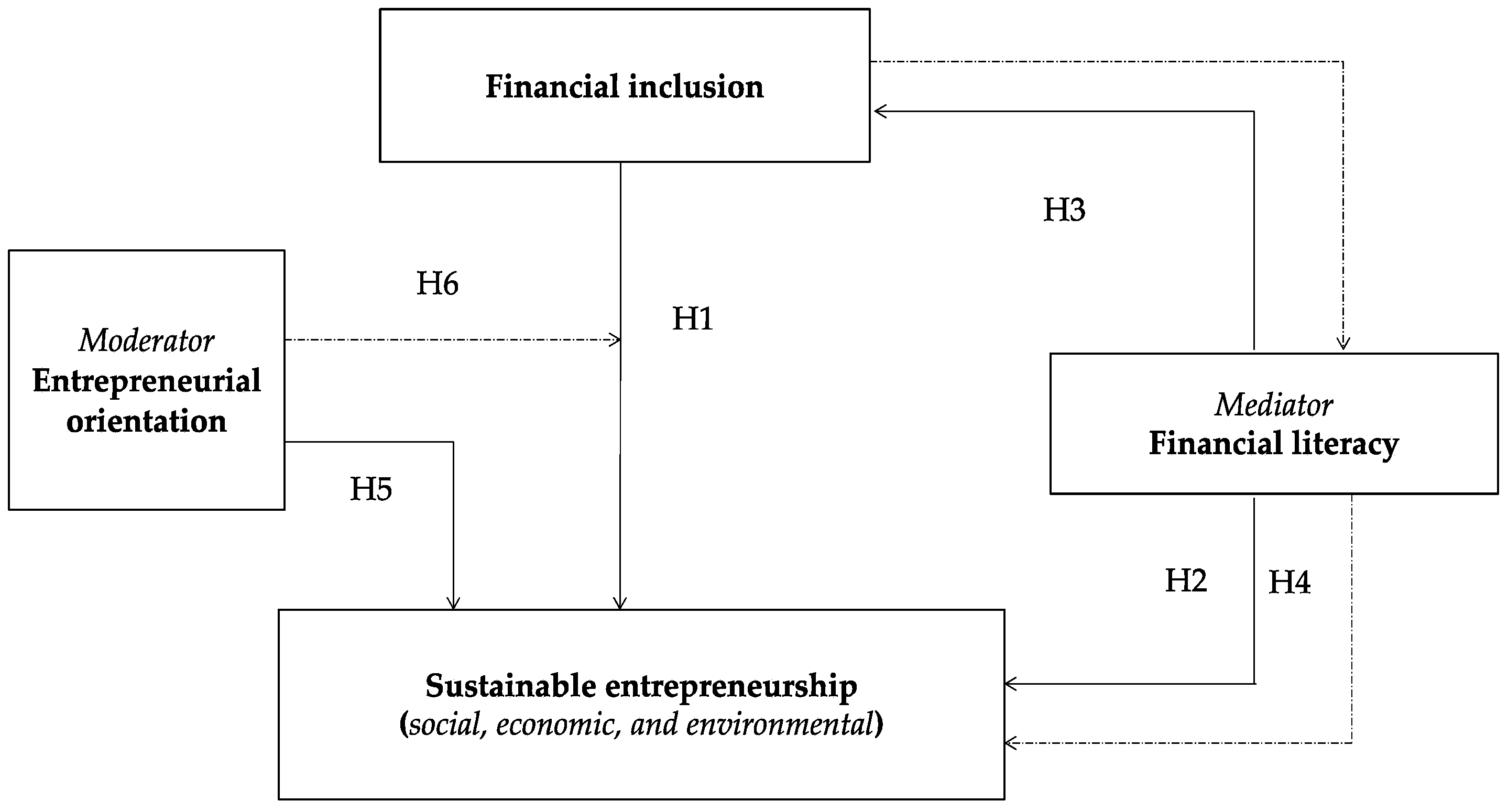

2.1. Conceptual Framework

2.2. Hypotheses

2.2.1. Financial Inclusion and Sustainable Entrepreneurship

2.2.2. Financial Literacy and Sustainable Entrepreneurship

2.2.3. Financial Literacy and Financial Inclusion

2.2.4. Mediating Effect of Financial Literacy on Financial Inclusion and Sustainable Entrepreneurship

2.2.5. Entrepreneurial Orientation and Sustainable Entrepreneurship

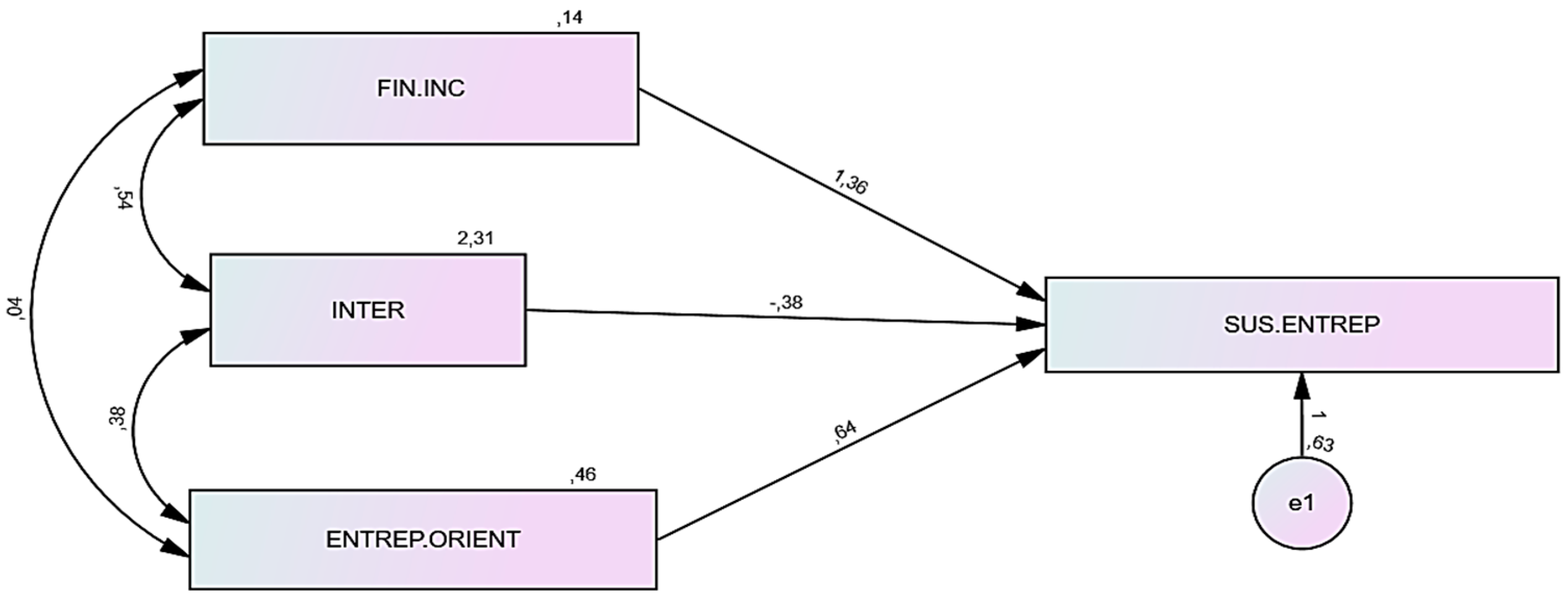

2.2.6. Moderating Role of Entrepreneurial Orientation on Financial Inclusion and Sustainable Entrepreneurship

3. Methodology

3.1. Questionnaire

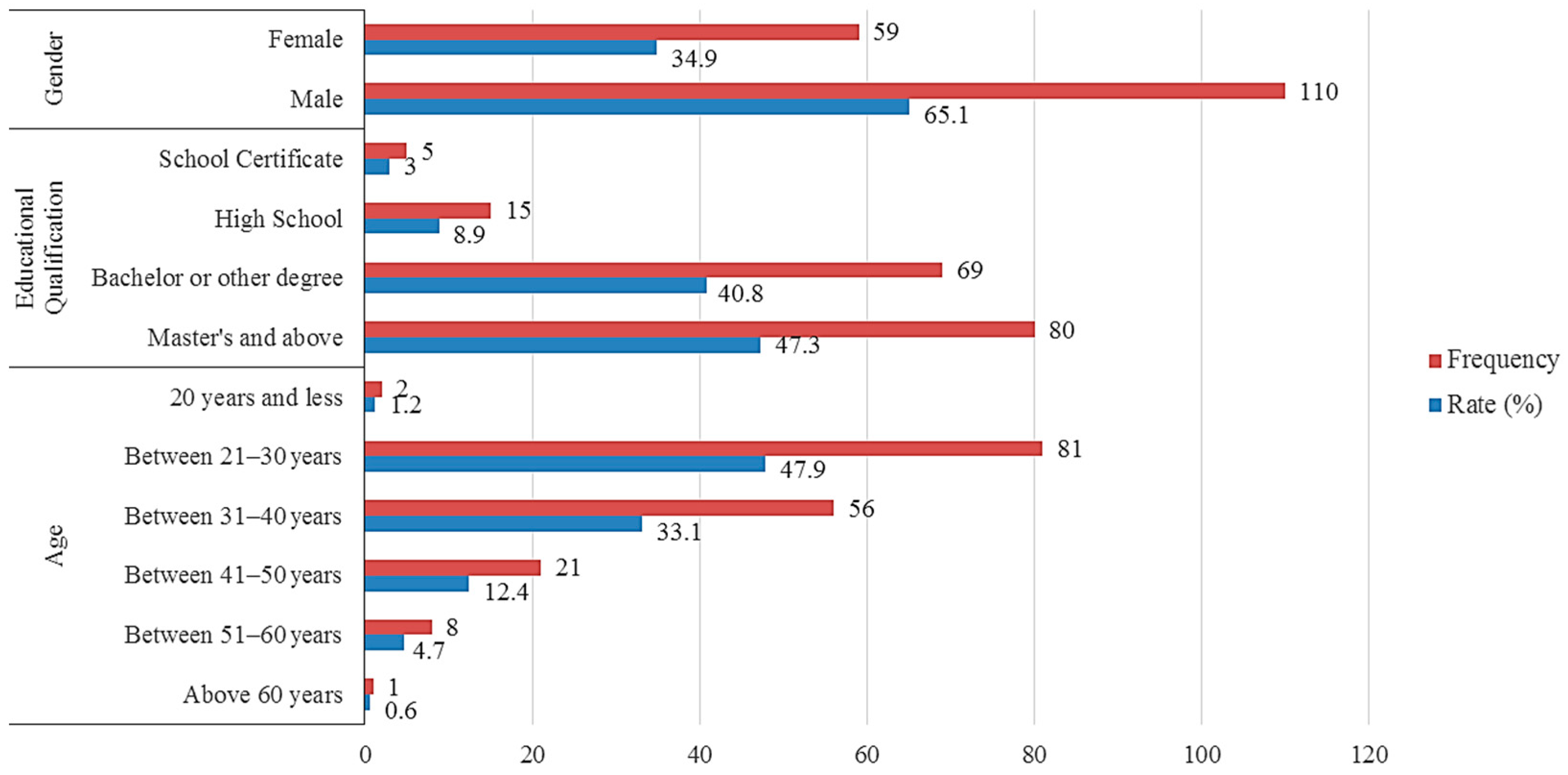

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Data Treatment

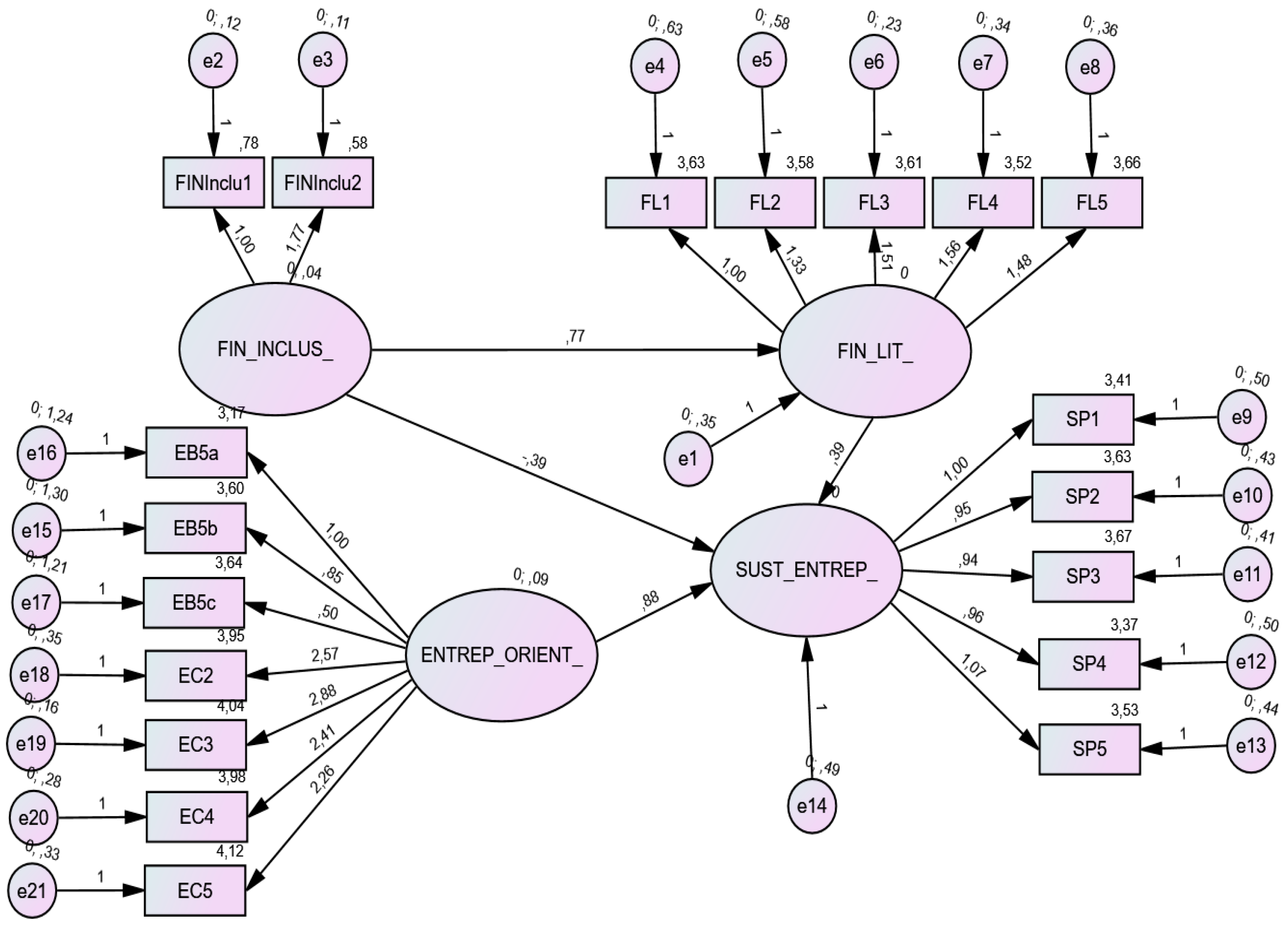

3.3.1. Parameters and Items

3.3.2. Approach and Assessments

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Preliminary Conditions

4.2. Measurement Model Assessment

4.3. Structural Model Assessment

4.4. Discussion of Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

Appendix A

| Approve | ☐ |

| Disapprove | ☐ |

- 1.

- Gender

| Male | ☐ |

| Female | ☐ |

- 2.

- Educational level

| Did not go to School | ☐ |

| Certificate of Schooling | ☐ |

| Baccalaureate | ☐ |

| Diploma/Bachelor | ☐ |

| Master and above | ☐ |

- 3.

- Age range

| Under 20 years old | ☐ |

| From 21 to 30 years old | ☐ |

| From 31 to 40 years old | ☐ |

| From 41 to 50 years old | ☐ |

| From 51 to 60 years old | ☐ |

| More than 60 years old | ☐ |

- 4.

- Your field of training is rather close to:

| Economics | ☐ |

| Commerce and Management | ☐ |

| Legal Sciences | ☐ |

| Literature Sciences | ☐ |

| Computer Sciences | ☐ |

| Mathematics, Physics, Chemistry | ☐ |

| Health Sciences | ☐ |

| Life and Earth Sciences | ☐ |

| Engineering Sciences | ☐ |

- 1.

- Have you ever started a business or taken over an existing one?

| Yes | ☐ answer question 2 |

| No | ☐ answer question 3 |

- 2.

- How long your business has been implemented

| Under 5 years | ☐ |

| From 6 to 10 years | ☐ |

| From 11 to 15 years | ☐ |

| From 16 to 20 years | ☐ |

| More than 20 years | ☐ |

- 3.

- Do you intend to create or take over a business?

| Yes | ☐ answer question 4 |

| No | ☐ |

- 4.

- What are the reasons that motivated you or could motivate you to undertake?

| Coming out of unemployment | ☐ |

| Having to carry on a family business | ☐ |

| Need for professional flexibility | ☐ |

| Wanting to increase one’s income | ☐ |

| Professional or personal dissatisfaction | ☐ |

| Insecurity in the current job | ☐ |

| Taking advantage of an untapped | |

| opportunity (Idea for a product/service that | |

| does not yet exist on the market) | ☐ |

| Be autonomous in decision-making | ☐ |

| Create your own job | ☐ |

- 5.

- In your opinion, what resources do we need to undertake? * Please check the box that you believe corresponds to the level of importance of each resource. ([1] Not at all important, [2] slightly important, [3] important, [4] very important, [5] extremely important) Only one answer possible per line.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Professional experience | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| Resources (Financial, Material, Technological) | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| Professional relations | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

- 1.

- Have you taken or participated in training on entrepreneurship?

| Yes | ☐ answer question 2 |

| No | ☐ |

- 2.

- What kind of training did you have?

| Entrepreneurship module in the university curriculum | ☐ |

| Awareness seminar | ☐ |

| Testimonials from entrepreneurs, professionals or experts | ☐ |

- 3.

- What institutions do you know?

| Program MOUKAWALATI | ☐ |

| Centres Régionaux d’Investissements (CRI) | ☐ |

| Program INTILAKA | ☐ |

| Program FORSA | ☐ |

| Initiative Nationale pour le développement Humain (INDH) | ☐ |

- 4.

- What is the nature of the programs you know?

| Public funding (grant) | ☐ |

| Private funding (loan) | ☐ |

| Training Monitoring | ☐ |

- 5.

- What information sources do you use to access information on entrepreneurship?

| Search engines/Web | ☐ |

| Social networks | ☐ |

| Professional relations | ☐ |

| Press/Specialized magazines | ☐ |

- 1.

- Do you, have an account in a bank, savings and credit institution, either individual or jointed to someone else? An account can be used to setting paid and receiving monetary transfers, making or receiving payments, savings, or deposits.

| Yes | ☐ |

| I don’t know | ☐ |

| No | ☐ |

- 2.

- In the last 12 months, have you utilized a bank or other financial institution account to save or put money apart?

| Yes | ☐ |

| I don’t know | ☐ |

| No | ☐ |

- 3.

- In the last 12 months, did you get loan from a bank or other financial institution?

| Yes | ☐ |

| I don’t know | ☐ |

| No | ☐ |

- 1.

- Entrepreneurial Competency

| Code | Item | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly Agree |

| EC1 | I can recognize opportunities | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| EC2 | I am creative and have a long-term view | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| EC3 | I combine both communication and leadership abilities | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| EC4 | I am proactive and make decisions in order to manage risks, uncertainty, and ambiguity. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| EC5 | I have skills in solving and fixing problems | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

- 2.

- Financial Literacy

| Code | Item | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree Strongly | Agree |

| FL1 | I am used to and know well financial instruments (e.g., bonds, stock, T-bill, future, contract, option, etc.) | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| FL2 | I use a cash book that I have to record all business expenses and incomes | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| FL3 | I elaborate an annual financial plan for my business that I often follow | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| FL4 | I make financial statements for my business (Balance Sheet, Income statement) | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| FL5 | I understand the information displayed in financial statements and use it to operate my business. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

- 3.

- Sustainable Performance

| Code | Item | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree Strongly | Agree |

| SP1 | My firm outperforms significant rivals in terms of environmental performance | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| SP2 | My firm outperforms significant rivals in terms of social performance | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| SP3 | My firm outperforms significant rivals in terms of employees retaining | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| SP4 | My firm outperforms significant rivals in terms of investment in society | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| SP5 | My firm outperforms significant rivals in terms of equilibrium between financial, social, and environmental aspects | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

References

- Adamu, M. Bala, and Mamman Suleiman. 2018. Financial Inclusion and Inclusive Growth: Evidence from West and East African Countries. Paper presented at 4th International Conference on Social Sciences (ICSS 2018)—Economics, Nile University, Abuja, Nigeria, March 21–22. [Google Scholar]

- AFI. 2023. Available online: https://www.afi-global.org/newsroom/news/afis-executive-director-wraps-up-highly-successful-financial-inclusion-meetings-with-bam-governor-and-unsgsa-delegation-in-morocco/ (accessed on 8 May 2023).

- Ahmad, Saleem, and Jihane Mokhchy. 2023. Corporate social responsibilities, sustainable investment, and the future of green bond market: Evidence from renewable energy projects in Morocco. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 30: 15186–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajide, Folorunsho M. 2020. Financial inclusion in Africa: Does it promote entrepreneurship? Journal of Financial Economic Policy 12: 687–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshebami, Ali Saleh, and Theyazn H. H. Aldhyani. 2022. The Interplay of Social Influence, Financial Literacy, and Saving Behavior among Saudi Youth and the Moderating Effect of Self-Control. Sustainability 14: 8780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bank Al-Maghrib. 2016. Annual Report. Available online: https://www.bkam.ma/en/Publications-and-research/Institutional-publications/Annual-report-presented-to-his-majesty-the-king/Annual-report-2016 (accessed on 8 May 2023).

- Bank Al-Maghrib. 2021. Annual Report. Available online: https://www.bkam.ma/en/Press-releases/Press-releases/2022/Bank-al-maghrib-annual-report-2021 (accessed on 8 May 2023).

- Bank Al-Maghrib. 2023. Available online: https://www.bkam.ma/en/Financial-inclusion/Overview (accessed on 8 May 2023).

- Baron, Reuben M., and David A. Kenny. 1986. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 51: 1173–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belz, F. Martin, and Julia K. Binder. 2015. Sustainable Entrepreneurship: A Convergent Process Model: Sustainable Entrepreneurship: A Convergent Process Model. Business Strategy and the Environment 26: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanken, Ward, Maria Cuaresma, René H. Wijffels, and Marcel Janssen. 2013. Cultivation of microalgae on artificial light comes at a cost. Algal Research 2: 333–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchi, Alberto, Bogdan Włodarczyk, Marek Szturo, and Duccio Martelli. 2021. The Effects of Financial Literacy on Sustainable Entrepreneurship. Sustainability 13: 5070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaghan, C., and Robert Venter. 2011. An Investigation of the Entrepreneurial Orientation, Context and Entrepreneurial Performance of inner-City Johannesburg Street Traders. Southern African Business Review 15: 1. [Google Scholar]

- Cardarelli, Roberto, Hyppolite W. Balima, Chiara Maggi, Adrian Alter, Jérôme Vacher, Matt Gaertner, Olivier Bizimana, Azhin Ihsan Abdulkarim, Karim Badr, Shant Arzoumanian, and et al. 2022. Informality, Development, and the Business Cycle in North Africa. Departmental Papers 2022(011). Available online: https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/journals/087/087-overview.xml (accessed on 25 November 2024).

- Chepngetich, Prisca. 2016. Effect of financial literacy and performance SMEs. Evidence from Kenya. American Based Research Journal 11: 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Claessens, Stijin, and Enrico Perotti. 2007. Finance and inequality: Channels and evidence. Journal of Comparative Economics 35: 748–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farny, Steffen, and Julia Binder. 2021. Sustainable Entrepreneurship. In World Encyclopedia of Entrepreneurship. Edited by L. P. Dana. Camberley: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 605–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Jingguang, and Leiming Li. 2023. Dual innovation of the business model: The regulatory role of entrepreneurial orientation in family firms. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, David. 2006. Sustainability Entrepreneurs, Ecopreneurs and the Development of a Sustainable Economy. Greener Management International 2006: 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, Nidhi, and Pankaj Madan. 2019. Benchmarking financial inclusion for women entrepreneurship—A study of Uttarakhand state of India. Benchmarking 26: 160–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grohmann, Antonia, Theres Klühs, and Lukas Menkhoff. 2018. Does financial literacy improve financial inclusion? Cross country evidence. World Development 111: 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joseph F., Jefferey J. Risher, Marko Sarstedt, and Christian M. Ringle. 2019. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review 31: 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joseph F., Jr., Christian M. Ringle, and Marko Sarstedt. 2013. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling: Rigorous applications, better results and higher acceptance. Long Range Planning 46: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joseph F., Jr., G. Tomas M. Hult, Christian M. Ringle, Marko Sarstedt, Nicholas P. Danks, and Soumya Ray. 2021. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook. Cham: Springer Nature, p. 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joseph F., Jr., William C. Black, Barry J. Babin, and Rolph E. Anderson. 2018. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed. London: Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-4737-5654-0. [Google Scholar]

- Halberstadt, Jantje, Christoph Schank, Mark Euler, and Rainer Harms. 2019. Learning Sustainability Entrepreneurship by Doing: Providing a Lecturer-Oriented Service-Learning Framework. Sustainability 11: 1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hockerts, Kai, and Rolf Wüstenhagen. 2010. Greening Goliaths versus emerging Davids—Theorizing about the role of incumbents and new entrants in sustainable entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing 25: 481–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, Md Aminul, Mohammad Aktaruzzaman Khan, Abu Zafar Muhammad Obaidullah, and M. Syed Alam. 2011. Effect of Entrepreneur and Firm Characteristics on the Business Success of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in Bangladesh. International Journal of Business and Management 6: 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Lili, Aihua Tong, Zhifei Hu, and Yifeng Wang. 2019. The impact of the inclusive financial development index on farmer entrepreneurship. PLoS ONE 14: e0216466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Iftikhar, Ismail Khan, Aziz Ullah Sayal, and Muhammad Zubair Khan. 2022. Does financial inclusion induce poverty, income inequality, and financial stability: Empirical evidence from the 54 African countries? Journal of Economic Studies 49: 303–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, Rex B. 2010. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modelling, 3rd ed. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, Rex B. 2016. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus, Sascha, J. P. Coen Rigtering, Mathew Hughes, and Vincdent Hosman. 2012. Entrepreneurial orientation and the business performance of SMEs: A quantitative study from the Netherlands. Review of Managerial Science 6: 161–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahlou, Kamal, Hicham Doghmi, and Friedrich Schneider. 2020. The Size and Development of the Shadow Economy in Morocco. Rabat: Bank Al-Maghrib. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/p/ris/bkamdt/2020_003.html (accessed on 25 November 2024).

- Li, Yong-Hui, Jing-Wen Huang, and Ming-Tien Tsai. 2009. Entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance: The role of knowledge creation process. Industrial Marketing Management 38: 440–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Yuan, Yongbin Zhao, Justin Tan, and Yi Liu. 2008. Moderating Effects of Entrepreneurial Orientation on Market Orientation-Performance Linkage: Evidence from Chinese Small Firms. Journal of Small Business Management 46: 113–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lontchi, Claude Bernard, Baochen Yang, and Yunpeng Su. 2022. The Mediating Effect of Financial Literacy and the Moderating Role of Social Capital in the Relationship between Financial Inclusion and Sustainable Development in Cameroon. Sustainability 14: 15093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, G. Tom, and Gregory G. Dess. 1996. Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. Academy of management Review 21: 135–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, Pablo, Frank Janssen, Katerina Nicolopoulou, and Kai Hockerts. 2018. Advancing sustainable entrepreneurship through substantive research. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research 24: 322–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napitupulu, Darmawan, J. Aabdel Kadar, and R. Kartika Jati. 2017. Validity testing of technology acceptance model based on factor analysis approach. Indonesian Journal of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science 5: 697–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyarko, Eunice Stella, Kofi Amoateng, and Aanthony Qabotoo Quame Aboagye. 2023. Financial inclusion and poverty: Evidence from developing economies. International Journal of Social Economics 50: 1719–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocampos, Lorraine 2023. Chapter 10: Financial Inclusion in Morocco. In Morocco’s Quest for Stronger And Inclusive Growth. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

- OECD. 2015. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/industry-and-services (accessed on 8 May 2023).

- OECD. 2017. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/industry-and-services (accessed on 8 May 2023).

- OECD. 2018. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/industry-and-services (accessed on 8 May 2023).

- OECD. 2019. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/fr/education/pisa-2018-assessment-and-analytical-framework_b25efab8-en (accessed on 8 May 2023).

- Okowa, Ezaal Vincent, and Moses Vincent. 2022. «Financial Inclusion-Income Inequality» Nexus in Nigeria: Evidence from Dynamic Ordinary Least Square (DOLS) Modeling Approach. International Journal of Research and Scientific Innovation 9: 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallant, Julie. 2020. SPSS Survival Manual: A Step by Step Guide to Data Analysis Using IBM SPSS, 7th ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, Amit, Ravi Kiran, and Rakesh Kumar Sharma. 2022. Investigating the Impact of Financial Inclusion Drivers, Financial Literacy and Financial Initiatives in Fostering Sustainable Growth in North India. Sustainability 14: 11061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, Orlando C., Tim Barnett, Sean Dwyer, and Ken Chadwick. 2004. Cultural Diversity in Management, Firm Performance, and the Moderating Role of Entrepreneurial Orientation Dimensions. Academy of Management Journal 47: 255–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sakanko, Musa Abdullahi, N. Abu, and Joseph E. David. 2019. Financial Inclusion: A Panacea for National Development in Nigeria. Paper presented at 2nd National Conference of the Faculty of Social Sciences, Captioned: “Emerging Socio Economics and Political Challenges and National Development”, Lafia, Nigeria, September 22–24. [Google Scholar]

- Sangeetha, R., Jain Mathew, and Sheethal C. Francline. 2017. Status of Financial Literacy Centers in Karnataka. Ushus Journal of Business Management 16: 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, Stefan, and Marcus Wagner. 2011. Sustainable entrepreneurship and sustainability innovation: Categories and interactions. Business Strategy and the Environment 20: 222–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlange, Lutz E. 2006. Stakeholder Identification in Sustainability Entrepreneurship. Greener Management International 2006: 13–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumpeter, Joseph A. 1934. The Theory of Economic Development: An Inquiry into Profits, Capital, Credits, Interest, and the Business Cycle. Piscataway: Transaction Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, Ashutosh, Niladri Das, and Surendra P. Singh. 2023. Causal association of entrepreneurship ecosystem and financial inclusion. Heliyon 9: e14596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Dipasha. 2016. Nexus between financial inclusion and economic growth: Evidence from the emerging Indian economy. Journal of Financial Economic Policy 8: 13–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, Noora. 2021. Factor analysis as a tool for survey analysis. American Journal of Applied Mathematics and Statistics 9: 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Vendant, and Somesh K. Sharma. 2016. Analyzing the moderating effects of respondent type and experience on the fuel efficiency improvement in air transport using structural equation modeling. European Transport Research Review 8: 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soyemi, Kenny, Olusola Enitan Olowofela, and Lateef Adewale Yunusa. 2020. Financial inclusion and sustainable development in Nigeria. Journal of Economics & Management 39: 105–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, Bryant M. 2021. The Ethical Use of Fit Indices in Structural Equation Modeling: Recommendations for Psychologists. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 783226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilley, Fiona, and William Young. 2006. Sustainability Entrepreneurs. Greener Management International 2006: 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triyono, Mochamad Bruri, Farid Mutohhari, Nur Kholifah, Muhammad Nurtanto, Hani Subakti, and Kiftian Hady Prasetya. 2023. Examining the Mediating-Moderating Role of Entrepreneurial Orientation and Digital Competence on Entrepreneurial Intention in Vocational Education. Journal of Technical Education and Training 15: 116–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNSGA. 2023. Available online: https://www.unsgsa.org/country-visits/morocco-has-opportunity-harness-digital-payments-fintech-and-green-finance-expand-financial-inclusion (accessed on 8 May 2023).

- Wales, William J., Jeffrey G. Covin, and Erik Monsen. 2020. Entrepreneurial Orientation: The Necessity of a Multi-Level Conceptualization. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 14: 639–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F. Y., and M. J. Tan. 2017. Integration of Pratt & Whitney Finance and Farmers’ Entrepreneurship: Mechanism, Dilemma and Path. Xuehai 6: 151–55. [Google Scholar]

- Westland, J. Christopher. 2019. Structural Equation Models: From Paths to Networks. Cham: Springer, vol. 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. 2019. Morocco 2019 Country Profile: Enterprise Surveys. Washington, DC: World Bank. Available online: https://www.enterprisesurveys.org/content/dam/enterprisesurveys/documents/country/Morocco-2019.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2023).

- World Bank. 2022. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/financialinclusion/overview (accessed on 8 May 2023).

- Ye, Jianmu, and KMMCB Kulathunga. 2019. How Does Financial Literacy Promote Sustainability in SMEs? A Developing Country Perspective. Sustainability 11: 2990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Constructs | Parameters | Items | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Financial Literacy | FIN_LIT_ | [FL1] [FL2] [FL3] [FL4] [FL5] | |

| Sustainable Entrepreneurship | SUS_ENTREP_ | [SP1] [SP2] [SP3] [SP4] [SP5] | |

| Entrepreneurial Orientation | Entrepreneurial Competency | ENTREP_ORIENT_ | [EC2] [EC3] [EC4] [EC5] |

| Entrepreneurial Behavior | [EB5a] [EB5b] [EB5c] | ||

| Financial Inclusion | FIN_INCLUS_ | [FINInclu1] [FINInclu2] | |

| Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin Adequacy | Measure of Sampling | 0.833 |

| Bartlett Test of Sphericity | Chi-Square (χ2) | 1636 |

| df | 171 | |

| σ | 0 |

| Constructs | Items | Loadings | CA | CR | AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Financial Literacy | [FL1} | 0.677 | 0.889 | 0.900 | 0.643 | |

| [FL2] | 0.786 | |||||

| [FL3] | 0.837 | |||||

| [FL4] | 0.847 | |||||

| [FL5] | 0.849 | |||||

| Sustainable Entrepreneurship | [SP1] | 0.712 | 0.874 | 0.890 | 0.619 | |

| [SP2] | 0.765 | |||||

| [SP3] | 0.771 | |||||

| [SP4] | 0.828 | |||||

| [SP5] | 0.850 | |||||

| Entrepreneurial Orientation | Entrepreneurial Competency | [EC2] | 0.796 | 0.777 | 0.930 | 0.656 |

| [EC3] | 0.848 | |||||

| [EC4] | 0.869 | |||||

| [EC5] | 0.776 | |||||

| Entrepreneurial Behavior | [EB5a] | 0.713 | ||||

| [EB5b] | 0.825 | |||||

| [EB5c] | 0.833 | |||||

| Financial Inclusion | [FINInclu1] | 0.824 | 0.545 | 0.803 | 0.671 | |

| [FINInclu2] | 0.814 | |||||

| ENTREP_ORIENT_ | FIN_LIT_ | FIN_INCLUS_ | SUS_ENTREP_ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ENTREP_ORIENT_ | 0.810 | 0.347 2 | 0.144 | 0.339 2 |

| FIN_LIT_ | 0.347 2 | 0.802 | 0.176 1 | 0.362 2 |

| FIN_INCLUS_ | 0.144 | 0.176 1 | 0.819 | 0.019 |

| SUS_ENTREP_ | 0.339 2 | 0.362 2 | 0.362 | 0.787 |

| SUS_ENTREP_ | FIN_LIT_ | FIN_INCLUS_ | ENTREP_ORIENT_ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SUS_ENTREP_ | - | - | - | - |

| FIN_LIT_ | 0.414 | - | - | - |

| FIN_INCLUS_ | 0.027 | 0.244 | - | - |

| ENTREP_ORIENT_ | 0.424 | 0.439 | 0.216 | - |

| Relationship | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | p-Value | Hypothesis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FIN_INCLUS_ → FIN_LIT_ | 0.771 | 0.345 | 2.237 | 0.025 1 | H3 accepted |

| ENTREP_ORIENT_ → SUST-ENTREP_ | 0.878 | 0.335 | 2.621 | 0.009 2 | H5 accepted |

| FIN_LIT_ → SUS_ENTREP_ | 0.389 | 0.118 | 3.285 | 0.001 3 | H2 accepted |

| FIN_INCLUS_ → SUS_ENTREP_ | −0.392 | 0.392 | −1 | 0.318 | H1 rejected |

| Direct Effects | Indirect Effects | Total Effects | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FIN_INCLUS_ > FIN_LIT_ > SUST_ENTREP_ | −0.392 | 0.3 1 | −0.092 | H4 is supported, and its indirect effect is statistically significant |

| Two-Tailed Significance | p = 0.398 | p = 0.013 | p = 0.192 | |

| The direct (unmediated) effect of financial inclusion (FIN_INCLUS_) on sustainable entrepreneurship (SUST_ENTREP_) is not significantly different from zero at the 0.05 level (p = 0.398, two-tailed). This result is based on a bootstrap approximation using two-sided bias-corrected confidence intervals. | The indirect (mediated) effect of financial inclusion (FIN_INCLUS_) on sustainable entrepreneurship (SUST_ENTREP_) is significantly different from zero at the 0.05 level (p = 0.013, two-tailed). This result is based on a bootstrap approximation using two-sided bias-corrected confidence intervals. | The total (direct and indirect) effect of financial inclusion (FIN_INCLUS_) on sustainable entrepreneurship (SUST_ENTREP_) is not significantly different from zero at the 0.05 level (p = 0.903, two-tailed). This result is based on a bootstrap approximation using two-sided bias-corrected confidence intervals. |

| Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FIN_INCLUS_→ SUST_ENTREP_ | 1.355 | 0.764 | 1.774 | 0.076 |

| INTER→ SUST_ENTREP_ | −0.383 | 0.2 | −1.91 | 0.056 |

| ENTREP_ORIENT→ SUST_ENTREP_ | 0.639 | 0.141 | 4.515 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zouitini, I.; El Hafdaoui, H.; Chetioui, H.; Tardif, P.-M.; Makhtari, M. Determinants of Sustainable Entrepreneurship in Morocco: The Role of Entrepreneurial Orientation, Financial Literacy, and Inclusion. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2024, 17, 548. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm17120548

Zouitini I, El Hafdaoui H, Chetioui H, Tardif P-M, Makhtari M. Determinants of Sustainable Entrepreneurship in Morocco: The Role of Entrepreneurial Orientation, Financial Literacy, and Inclusion. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2024; 17(12):548. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm17120548

Chicago/Turabian StyleZouitini, Ikram, Hamza El Hafdaoui, Hajar Chetioui, Pierre-Martin Tardif, and Mohamed Makhtari. 2024. "Determinants of Sustainable Entrepreneurship in Morocco: The Role of Entrepreneurial Orientation, Financial Literacy, and Inclusion" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 17, no. 12: 548. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm17120548

APA StyleZouitini, I., El Hafdaoui, H., Chetioui, H., Tardif, P.-M., & Makhtari, M. (2024). Determinants of Sustainable Entrepreneurship in Morocco: The Role of Entrepreneurial Orientation, Financial Literacy, and Inclusion. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(12), 548. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm17120548