Knowledge Collaboration among Tax Professionals through the Lens of a Community of Practice

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

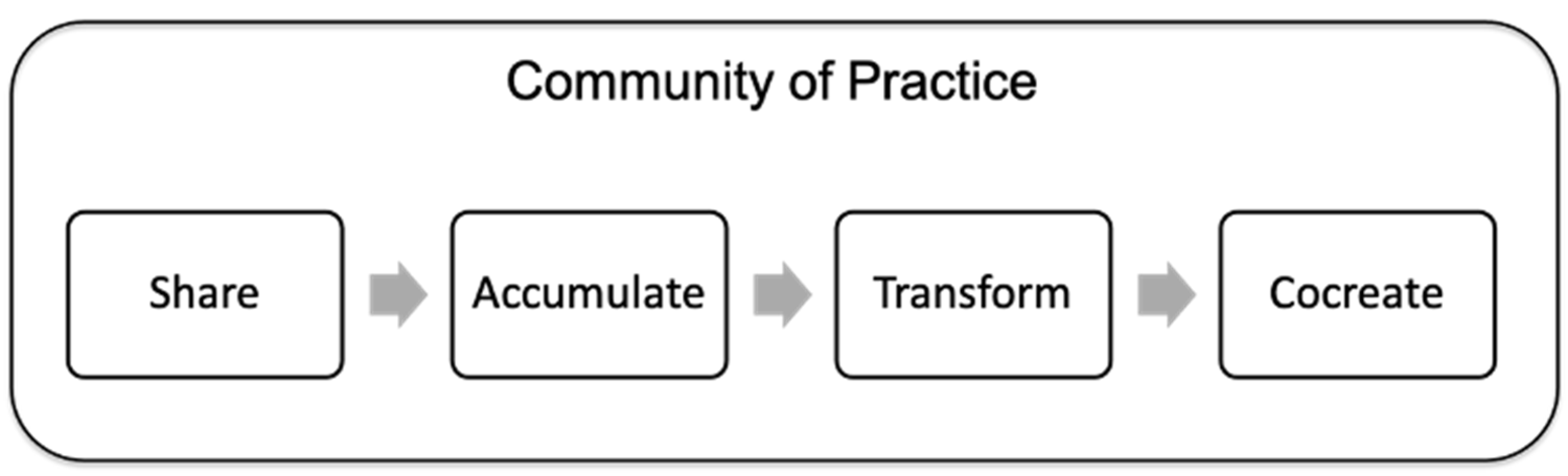

2.1. Knowledge Collaboration Processes in Communities

2.2. Factor and Process Studies on CoPs

2.3. Tax Practices

3. Research Methodology

4. Results

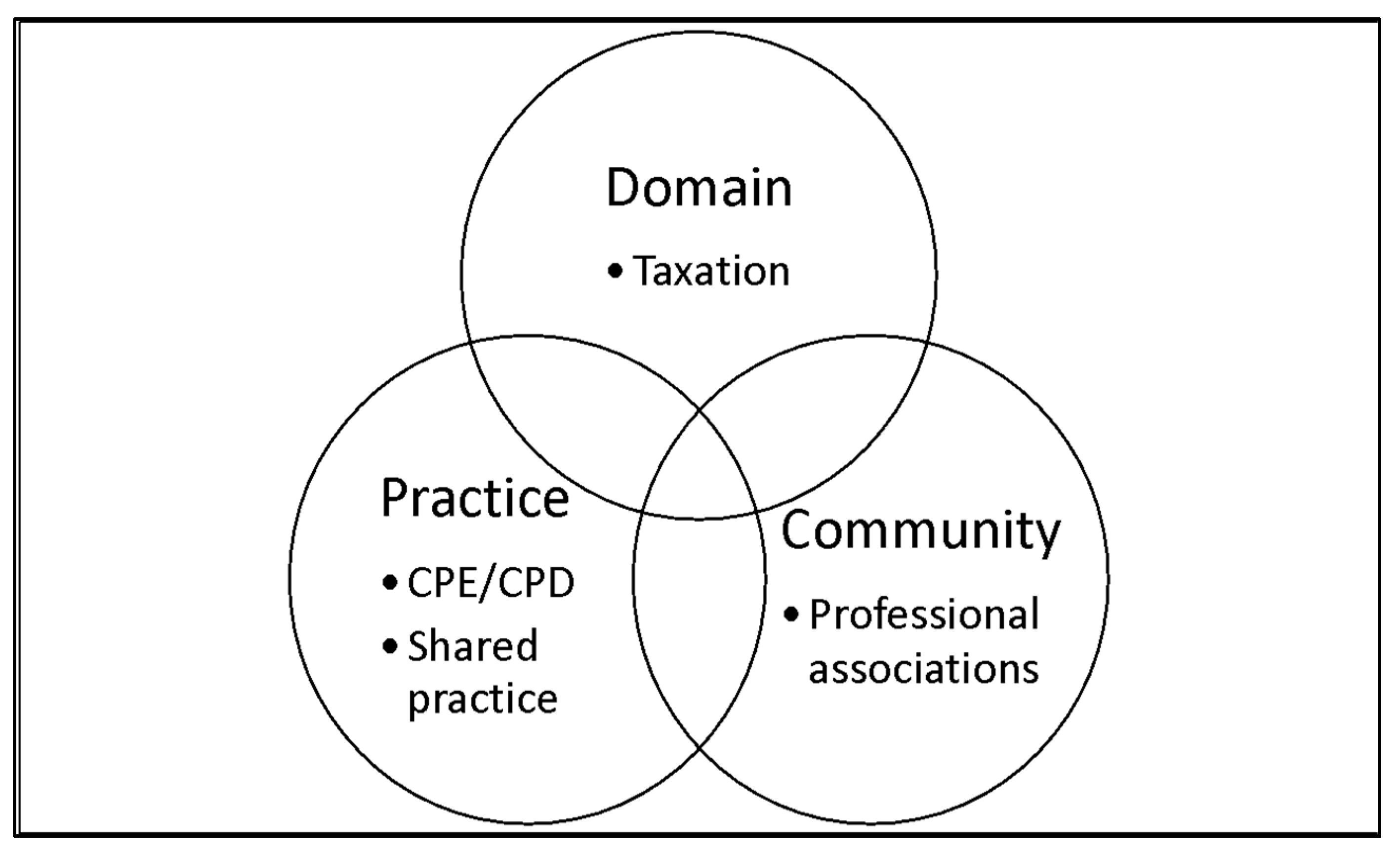

4.1. Malaysian Accounting Associations as CoPs

4.1.1. Tax Knowledge as the Knowledge Domain

4.1.2. A Professional Association as a Community

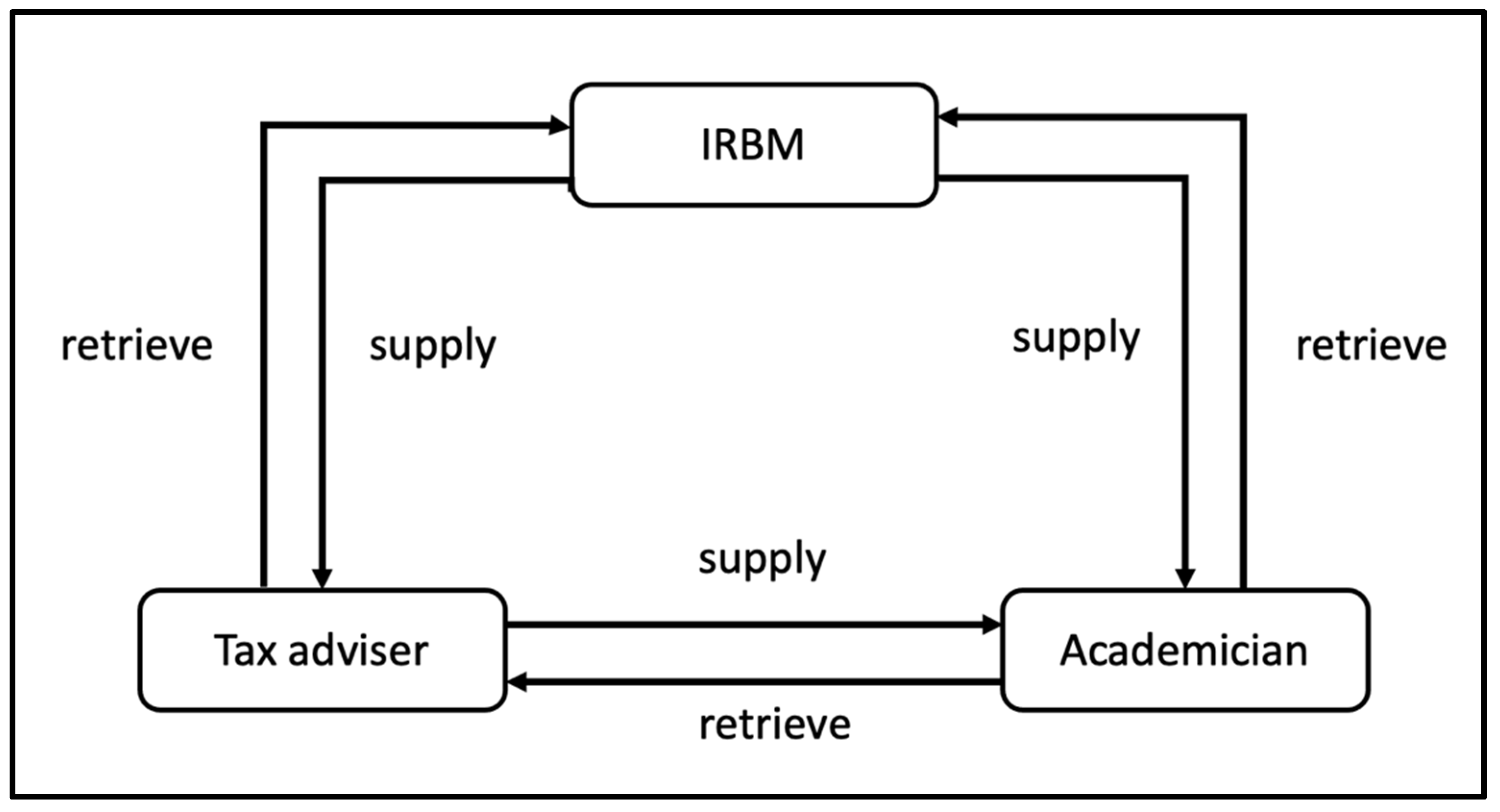

4.1.3. Members in the CoP

4.1.4. Informal Communication and Interaction among Members

… clients provide information and documentation prior to the preparation of their tax returns; they might not like the result … Then, they return with more documentation and request a re-run … It will become more complicated, and it requires me to discuss with my peers or seniors and seek their opinion at any time during the day … This is because we need to be flexible while remaining tax compliant.(Tax consultant)

We do not have many lecturers who specialise in taxation in a faculty. Normally, there’s only one or two lecturers teaching the subject… The syllabus, especially public ruling, changes on a yearly basis… If I can’t interpret the published guide well, I will refer to my industrial contacts … Better still to get in touch with employees from IRBM… Usually, they can provide ideas about particular tax laws, policies and procedures.(Lecturer)

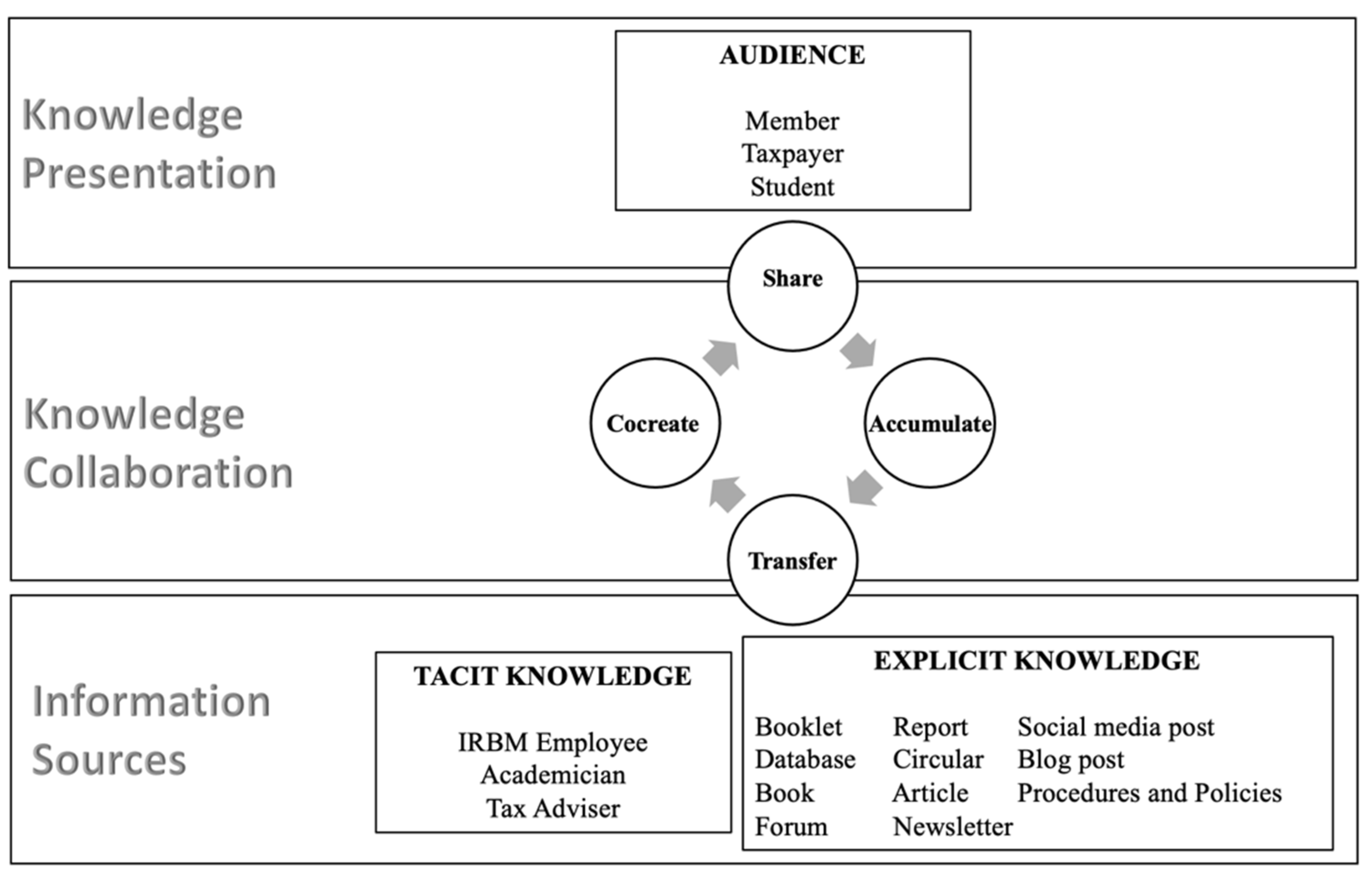

4.2. Knowledge Collaboration Process

4.3. Summary of Knowledge Collaboration and Interaction among Members

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Interview Guide

| Area of Interest | Questions |

| Share |

|

| Transfer |

|

| Accumulate |

|

| Transform |

|

| Cocreate |

|

| Technology |

|

| Community of Practice |

|

References

- Adler, Paul S. 2001. Market, hierarchy, and trust: The knowledge economy and the future of capitalism. Organization Science 12: 215–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Sarmad, Adalberto Rangone, and Muhammad Farooq. 2022. Corporate Taxation and Firm-Specific Determinants of Capital Structure: Evidence from the UK and US Multinational Firms. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 15: 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rahamneh, Nayef Mohammad, and Zainol Bidin. 2022. The Effect of Tax Fairness, Peer Influence, and Moral Obligation on Sales Tax Evasion Among Jordanian SMEs. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 15: 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amidon, Debra M. 1998. The evolving community of knowledge practice: The Ken awakening. International Journal of Technology Management 16: 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, Shahnaz Noorul, Putri Zaqqeya Amin Buhari, Abu Sofian Yaacob, and Zuberi Iddy. 2022. Exploring the Influence of Tax Knowledge in Increasing Tax Compliance by Introducing Tax Education at Tertiary Level Institutions. Open Journal of Accounting 11: 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, Christopher S., Jennifer L. Blouin, Alan D. Jagolinzer, and David F. Larcker. 2015. Corporate governance, incentives, and tax avoidance. Journal of Accounting and Economics 60: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azungah, Theophilus. 2018. Qualitative research: Deductive and inductive approaches to data analysis. Qualitative Research Journal 18: 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Saad, Ghazi. 2020. Roles of Communities of Practice in Intra-Organizational Coordination of Productive Knowledge. International Transaction Journal of Engineering Management & Applied Sciences & Technologies 11: 11a12h. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergner, Sören M., and Jost H. Heckemeyer. 2017. Simplified tax accounting and the choice of legal form. European Accounting Review 26: 581–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornman, Marina, and Pusheletso Ramutumbu. 2019. A conceptual framework of tax knowledge. Meditari Accountancy Research 27: 823–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, John Seely, and Paul Duguid. 1991. Organizational learning and communities-of-practice: Toward a unified view of working, learning, and innovation. Organization Science 2: 40–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Melanie, and Catherine Peck. 2018. Expanding the landscape: Developing knowledgeability through communities of practice. International Journal for Academic Development 23: 232–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caliskan, Koray. 2022. The Elephant in the Dark: A New Framework for Cryptocurrency Taxation and Exchange Platform Regulation in the US. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 15: 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, Teresa J., and Bryan Adkins. 2017. Situated learning, communities of practice, and the social construction of knowledge. In Theory and Practice of Adult and Higher Education. Charlotte: Information Age Publishing, pp. 113–117. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Qiang, and Yanru Chang. 2020. Influencing factors of knowledge collaboration effects in knowledge alliances. Knowledge Management Research & Practice 18: 380–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Mina. 2006. Communities of practice: An alternative learning model for knowledge creation. British Journal of Educational Technology 37: 143–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Mei-Tai, Rajiv Khosla, and Toyoaki Nishida. 2012. Communities of practice model driven knowledge management in multinational knowledge-based enterprises. Journal of Intelligent Manufacturing 23: 1707–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramton, Catherine Durnell. 2001. The mutual knowledge problem and its consequences for dispersed collaboration. Organization Science 12: 346–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, Janet A., Andrea L. Murphy, Syed Sibte Raza Abidi, Douglas Sinclair, and Patrick J. McGrath. 2009. Bridging the gap: Knowledge seeking and sharing in a virtual community of emergency practice. Evaluation & the Health Professions 32: 314–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, Li. 2009. Research on knowledge collaboration elements and procedural model of enterprise clusters. Library and Information Service 53: 76. [Google Scholar]

- Davenport, Elisabeth. 2001. Knowledge management issues for online organisations: ‘Communities of practice’ as an exploratory framework. Journal of Documentation 57: 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa, Clarice Francisco, and Elisabete Gonçalves de Souza. 2019. Communities of practice: Learning and sharing of knowledge between workers in organizations. Em Questao 25: 348–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyreng, Scott D., Michelle Hanlon, and Edward L. Maydew. 2019. When does tax avoidance result in tax uncertainty? The Accounting Review 94: 179–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, Knut, and Lars Fallan. 1996. Tax knowledge and attitude towards taxation: A report on a quasi experiment. Journal of Economic Psychology 17: 387–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evnitskaya, Natalia, and Tom Morton. 2011. Knowledge construction, meaning-making and interaction in CLIL science classroom communities of practice. Language and Education 25: 109–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraj, Samer, Sirkka L. Jarvenpaa, and Ann Majchrzak. 2011. Knowledge collaboration in online communities. Organization Science 22: 1224–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraj, Samer, Srinivas Kudaravalli, and Molly Wasko. 2015. Leading collaboration in online communities. MIS Quarterly 39: 393–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gammelgaard, Jens. 2010. Knowledge retrieval through virtual communities of practice. Behaviour & Information Technology 29: 349–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabher, Gernot, and Oliver Ibert. 2014. Distance as asset? Knowledge collaboration in hybrid virtual communities. Journal of Economic Geography 14: 97–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groenland, Edward AG, and Gery M. van Veldhoven. 1983. Tax evasion behaviour: A psychological framework. Journal of Psychological Behaviour 3: 129–44. [Google Scholar]

- Hafeez, Khalid, Fathalla M. Alghatas, Pantea Foroudi, Bang Nguyen, and Suraksha Gupta. 2019. Knowledge sharing by entrepreneurs in a virtual community of practice (VCoP). Information Technology & People 32: 405–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hantono, Hantono. 2021. Knowledge, Tax Awareness, Tax Morale towards Tax Compliance Boarding House Tax. International Journal of Research–Granthaalayah 9: 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Norul Syuhada Abu, Mohd Rizal Palil, Rosiati Ramli, and Ruhanita Maelah. 2022. Enhancing Tax Compliance in Malaysia: Does Tax Learning and Education Matter? International Business Education Journal 15: 18–29. [Google Scholar]

- Hasseldine, John, Kevin Holland, and Pernill GA van der Rijt. 2012. The management of tax knowledge. In Taxation. London: Routledge, pp. 156–62. [Google Scholar]

- Howells, Jeremy, Ronnie Ramlogan, and Shu-Li Cheng. 2012. Innovation and university collaboration: Paradox and complexity within the knowledge economy. Cambridge Journal of Economics 36: 703–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Nen-Ting, Chiu-Chi Wei, and Wei-Kou Chang. 2007. Knowledge management: Modeling the knowledge diffusion in community of practice. Kybernetes 36: 607–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishiyama, Nobutaka. 2016. Role of knowledge brokers in communities of practice in Japan. Journal of Knowledge Management 20: 1302–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivcovici, Adamina, Ian McLoughlin, Alka Nand, and Ananya Bhattacharya. 2021. Identity reconciliation and knowledge mobilization in a mandated community of practice. Journal of Knowledge Management 26: 763–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iverson, Joel O., and Robert D. McPhee. 2008. Communicating knowing through communities of practice: Exploring internal communicative processes and differences among CoPs. Journal of Applied Communication Research 36: 176–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvenpaa, Sirkka L., and Ann Majchrzak. 2010. Research commentary—Vigilant interaction in knowledge collaboration: Challenges of online user participation under ambivalence. Information Systems Research 21: 773–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings Mabery, Mamie, Lynn Gibbs-Scharf, and Debra Bara. 2013. Communities of practice foster collaboration across public health. Journal of Knowledge Management 17: 226–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, Su-Hwan, Young-Gul Kim, and Joon Koh. 2011a. Individual, social, and organizational contexts for active knowledge sharing in communities of practice. Expert Systems with Applications 38: 12423–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, Suhwan, Young-Gul Kim, and Joon Koh. 2011b. An integrative model for knowledge sharing in communities-of-practice. Journal of Knowledge Management 15: 251–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, Rasmus, Kasper Edwards, Enrico Scarso, and Christine Ipsen. 2021. Improving public sector knowledge sharing through communities of practice. Vine Journal of Information and Knowledge Management Systems 51: 318–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakimoto, Takeshi, Yasutaka Kamei, Masao Ohira, and Ken-ichi Matsumoto. 2006. Social network analysis on communications for knowledge collaboration in OSS communities. Paper presented at the International Workshop on Supporting Knowledge Collaboration in Software Development (KCSD’06), September 18–22; pp. 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Kasipillai, Jeyapalan. 1997. Aspects of the Hidden Economy and Tax Non-Compliance in Malaysia. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, University of New England, Armidale, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Khalid, Muhammad Yusof Abdul, Siti Zaidah Turmin, and Mohd Rizal Palil. 2021. Understanding Corporate Tax Avoidance and the Causal Factors: Some Evidence from Malaysia. International Journal of Academic Research in Accounting Finance and Management Sciences 11: 271–283. [Google Scholar]

- Kimmerle, Joachim, Ansgar Thiel, Kim-Kristin Gerbing, Martina Bientzle, Iassen Halatchliyski, and Ulrike Cress. 2013. Knowledge construction in an outsider community: Extending the communities of practice concept. Computers in Human Behavior 29: 1078–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara, Beatriz, Francesca Cañas, Antonieta Vidal, Núria Nadal, Ferran Rius, Eugeni Paredes, Marta Hernández, Francisco J. Maravall, Josep Franch-Nadal, Ferran Barbé, and et al. 2017. Knowledge management through two virtual communities of practice (Endobloc and Pneumobloc). Health Informatics Journal 23: 170–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lave, Jean, and Etienne Wenger. 1991. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Yung-Ming, and Jhih-Hua Jhang-Li. 2010. Knowledge sharing in communities of practice: A game theoretic analysis. European Journal of Operational Research 207: 1052–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Fu-ren, and Chih-Ming Hsueh. 2006. Knowledge map creation and maintenance for virtual communities of practice. Information Processing & Management 42: 551–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Chih-Chung, Ting-Peng Liang, Balaji Rajagopalan, Vallabh Sambamurthy, and Jason Chia-Hsien Wu. 2011. Knowledge-sharing as social exchange: Evidence from a meta-analysis. Pacific-Asia Journal of the Association for Information Systems 3: 21–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Fengjun, Zhengkui Lin, and Yi Qu. 2020. A system dynamics investigation of knowledge collaboration in online encyclopedias based on activity theory. Kybernetes 50: 1784–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeski, Karen, and Sandra Schefkind. 2021. A Demonstration of Knowledge Translation in A Transition Community of Practice. Journal of Occupational Therapy Schools and Early Intervention 14: 225–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, Osama, Mustafa Abu Salah, and Linda Askenäs. 2011. Wiki collaboration in organizations: An exploratory study. Paper presented at the 19th European Conference in Information Systems, Helsinki, Finland, June 9–11. [Google Scholar]

- Marsick, Victoria J., Andrew K. Shiotani, and Martha A. Gephart. 2014. Teams, communities of practice, and knowledge networks as locations for learning professional practice. In International Handbook of Research in Professional and Practice-Based Learning. Edited by Stephen Billett, Christian Harteis and Hans Gruber. Dordrecht: Springer, vols. 1–2, pp. 1021–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitran, Daniela, Natalita Burduc, and Paul Tanasescu. 2009. Communities of practice in organizations: A strategy for sharing and building knowledge. Metalurgia International 14: 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamad Judi, Hairulliza, Hanimastura Hashim, and Tengku Siti Meriam Tengku Wook. 2018. Knowledge Sharing Driving Factors in Technical Vocational Education and Training Institute Using Content Analysis. Asia-Pacific Journal of Information Technology and Multimedia 7: 11–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, Judy, and Tony Burch. 2009. Communities of Practice in Academe (CoP-iA): Understanding academic work practices to enable knowledge building capacities in corporate universities. Oxford Review of Education 35: 227–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbamichael, Hermon B., and Stuart Warden. 2018. Information and knowledge sharing within virtual communities of practice. South African Journal of Information Management 20: a956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoh, Umale, Muzainah Mansor, and Marhaiza Ibrahim. 2021. Improving knowledge management efficiency and tax administration performance through leadership styles and skills. Malaysian Journal of Qualitative Research 7: 70–84. [Google Scholar]

- Omidvar, Omid, and Roman Kislov. 2014. The Evolution of the Communities of Practice approach: Toward knowledgeability in a landscape of practice—An Interview with Etienne Wenger-Trayner. Journal of Management Inquiry 23: 266–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palil, Mohd Rizal. 2005. Taxpayers knowledge: A descriptive evidence on demographic factors in Malaysia. Jurnal Akutansi & Keuangan 7: 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Shan L., and Dorothy E. Leidner. 2003. Bridging communities of practice with information technology in pursuit of global knowledge sharing. Journal of Strategic Information Systems 12: 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Hyunjung, and Sung Joo Park. 2016. Communication behavior and online knowledge collaboration: Evidence from Wikipedia. Journal of Knowledge Management 20: 769–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramutumbu, Pusheletso. 2016. Tax Compliance Behaviour of Guest House Owners. Johannesburg: University of Johannesburg. [Google Scholar]

- Randhawa, Krithika, Emmanuel Josserand, Jochen Schweitzer, and Danielle Logue. 2017. Knowledge collaboration between organizations and online communities: The role of open innovation intermediaries. Journal of Knowledge Management 21: 1293–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rheingold, Howard. 2000. The Virtual Community: Homesteading on the Electronic Frontier, revised ed. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Salavisa, Isabel, Cristina Sousa, and Margarida Fontes. 2012. Topologies of innovation networks in knowledge-intensive sectors: Sectoral differences in the access to knowledge and complementary assets through formal and informal ties. Technovation 32: 380–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schofield, Keith, Bejan David Analoui, James Brooks, and Syed Fawzi Hussain. 2018. Competitive communities of practice, knowledge sharing, and Machiavellian participation: A case study. International Journal of Training and Development 22: 210–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setyorini, Riski, GS Achmad Daengs, Mahjudin, Andi Reni, Dwi Ermayanti Susilo, and Rahmat Hidayat. 2019. Knowledge management of financial performance for tax amnesty policy. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 1175: 012215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Norman Makoto, Hiroko N. Wilensky, and David F. Redmiles. 2012. Doing business with theory: Communities of practice in knowledge management. Computer Supported Cooperative Work-the Journal of Collaborative Computing 21: 111–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Christine Nya-Ling, and Shuhaida Md. Noor. 2013. Knowledge management enablers, knowledge sharing and research collaboration: A study of knowledge management at research universities in Malaysia. Asian Journal of Technology Innovation 21: 251–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utomo, Suryo, Mohd Rizal Palil, Romlah Jaffar, and Rosiati Ramli. 2015. Shareholder’s Political Motive and Corporate Tax Avoidance. Asian Journal of Accounting & Governance 6: 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatraman, Sitalakshmi, and Ramanathan Venkatraman. 2018. Communities of Practice Approach for Knowledge Management Systems. Systems 6: 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahab, Raja Azhan Syah Raja, and Azuraliza Abu Bakar. 2021. Digital Economy Tax Compliance Model in Malaysia using Machine Learning Approach. Sains Malaysiana 50: 2059–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanberg, John, Amy Javernick-Will, and John E. Taylor. 2017. Mechanisms to Initiate Knowledge-Sharing Connections in Communities of Practice. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 143: 04017085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Chen-Ya, Hsin-Yi Yang, and Seng-cho T. Chou. 2008. Using peer-to-peer technology for knowledge sharing in communities of practices. Decision Support Systems 45: 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Jun, Ruilin Zhang, Jin-Xing Hao, and Xuanyi Chen. 2019. Motivation factors of knowledge collaboration in virtual communities of practice: A perspective from system dynamics. Journal of Knowledge Management 23: 466–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenger, Etienne. 2011. Communities of Practice: A Brief Introduction. Eugene: Scholars Bank University of Oregon. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/1794/11736 (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Yue, Wu, and Gu Xin. 2012. Knowledge Collaboration Process in Industry-university-research Institute Collaborative Innovation. Forum on Science and Technology in China 10: 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Zamri, Inani Husna, and Anushia Ithiran. 2021. An Observation of Knowledge Sharing Activities in a Virtual Community of Practice. In Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems. Atlanta: Association for Information Systems (AIS), p. 210. Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/pacis2021/210 (accessed on 6 March 2022).

- Zimitat, Craig. 2007. Capturing community of practice knowledge for student learning. Innovations in Education and Teaching International 44: 321–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Xiaodong, and Kai Wang. 2016. University-industry knowledge synergy innovation in regional innovation ecosystems: Practical issues, theoretical basis and research agenda. Journal of Zhejiang University (Humanities and Social Sciences) 46: 5–18. [Google Scholar]

| Source | Description |

|---|---|

| Interview | Academicians–14 interviews |

| IRBM employees–3 interviews | |

| Tax advisers–12 interviews Category 1 (3 interviews) Category 2 (6 interviews) Category 3 (3 interviews) | |

| Field notes | Observations during the interview. |

| Archival data | Websites, media releases, books, and scholarly journals |

| Activity | Example of Activities | Association(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Webinar | Tax withholding, FY 2020 transfer-pricing report, payroll-tax computation. | MIA, CPA |

| Tax audit, tax appeal procedures, interest expense. | ACCA, CTIM, IRBM | |

| Tax-aligned mergers and acquisitions, tax litigation, tax audits, and investigations. | CTIM | |

| Implication for business restructuring, public rulings in 2020 and 2021, employee tax reporting. | CPA, IRBM | |

| Malaysia Budget 2021 | Ernst and Young | |

| Talent transfer to Malaysia, transfer pricing, and payment to individuals. | KPMG | |

| i. BDO Tax Webinar: Updates on Service Tax ii. BDO Tax Budget Seminar 2019 | BDO | |

| Case Study | Deferred taxation in complex transactions and events | MIA |

| eLearning | Ethics in tax | MIA |

| Expert hour, transfer-pricing updates, tax awareness | Crowe Horwath | |

| Virtual Conference/Conference | i. Data Intelligence and Analytics 2.0 Conference for Public Sector ii. Islamic Finance Conference 2021 | MIA |

| MIA Malaysian Tax Conference 2021 | ACCA, MIA, CIMA, MICPA | |

| i. Tax Max ii. National Tax Conference 2019 iii. Transfer Pricing Conference 2019 | Deloitte, IRBM, CPA, MIA | |

| In House Training | Tailor-made programs | MIA |

| Technical Resources | Budget booklets, cases, public rulings, budget and financial bills, service taxes and dialogues with IRB and Customs: technical, operational, desire working group, workshops. | MIA |

| Taxation in Malaysia–by country resources, including tax treaties, news and developments, rates and guides, library collections. | ICAEW | |

| Public Rulings | IRBM | |

| Surveillance and Enforcement | Conducts practice and financial statements, review, continuing professional education. compliance audit, investigation, and disciplinary proceedings | MIA |

| i. Review and set guidelines in Malaysia–International Accounting Standards (IAS) and International Standards on Auditing (ISA) Develop accounting and reporting standards for specialised industries (e.g., insurance, banking, and financial services) | MICPA | |

| Member’s Handbook | Provides technical and professional standards. | MICPA |

| Factsheets and guidelines | ACCA | |

| Commemorative Lecture | 63rd Anniversary Commemorative Lecture in July 2021 | MICPA |

| Publications | Approved Accounting Standards Malaysian Financial Reporting Standards (MFRS) and Private Entities Reporting Standard (MPERS) | MICPA |

| Technical updates, tax and investment review, budget commentary and tax information | MICPA | |

| Books and magazines and the Malaysian Accountant Journal | MICPA, CTIM, and MIA | |

| The Tax Guardian journal, published quarterly | CTIM | |

| Articles such as “Transfer pricing update: Malaysia tightens transfer pricing compliance requirements, and Budget 2022–Part I” (Tax Espresso Special Edition) | BDO Deloitte | |

| TaXavvy | PricewaterhouseCoopers | |

| e-Circular/Circular | Loans Guarantee (Bodies Corporate) (Remission of Tax and Stamp Duty) (No. 2) Order 2021 [P.U. (A) 322/2021] | CTIM |

| Monthly newsletter via email to taxpayers | LHDNM | |

| Tax Alerts subscription | Ernst and Young | |

| Tax Espresso subscription | Deloitte | |

| KPMG’s insights subscription | KPMG | |

| Newsletter–Tax | Crowe Horwath | |

| Blog/Discussion board | Tax Whiz Club (LinkedIn group) | KPMG |

| Our Perspective on Tax | PricewaterhouseCoopers |

| Process | Description | Activities |

|---|---|---|

| Share | Associations to members: Knowledge, insight, and technical expertise. | Training Webinars Newsletters Blog Social media Forum |

| Members to associations: Compilation of clients’ feedback and cases relevant to public rulings implementation. | Case studies Meeting Roundtable Forum | |

| Member to member: Operational and technical tax knowledge. | Meeting Roundtable Coffee talk Stories | |

| Accumulate | Associations: qualifications and professional developments. | Continuing Professional Education (CPE) Continuing Professional Development (CPD) Engagement for industry professionals Research |

| Transform | Associations: explicit knowledge. | Newsletter Documentation Articles |

| Members: convert explicit knowledge to tacit knowledge and vice versa. | Write books and articles Talk Stories Research | |

| Cocreate | Members engage in a design or problem-solving process to produce a mutually valued outcome. | Case studies Joint engagement in inquiry |

| IRBM | Academician | Tax Adviser | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IRBM |

|

|

|

| Academician |

|

| |

| Tax Adviser |

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bahar, N.; Bahri, S.; Zakaria, Z. Knowledge Collaboration among Tax Professionals through the Lens of a Community of Practice. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2022, 15, 439. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm15100439

Bahar N, Bahri S, Zakaria Z. Knowledge Collaboration among Tax Professionals through the Lens of a Community of Practice. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2022; 15(10):439. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm15100439

Chicago/Turabian StyleBahar, Nurhidayah, Shamshul Bahri, and Zarina Zakaria. 2022. "Knowledge Collaboration among Tax Professionals through the Lens of a Community of Practice" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 15, no. 10: 439. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm15100439

APA StyleBahar, N., Bahri, S., & Zakaria, Z. (2022). Knowledge Collaboration among Tax Professionals through the Lens of a Community of Practice. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 15(10), 439. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm15100439