How Market Orientation Impacts Customer’s Brand Loyalty and Buying Decisions

Abstract

1. Introduction

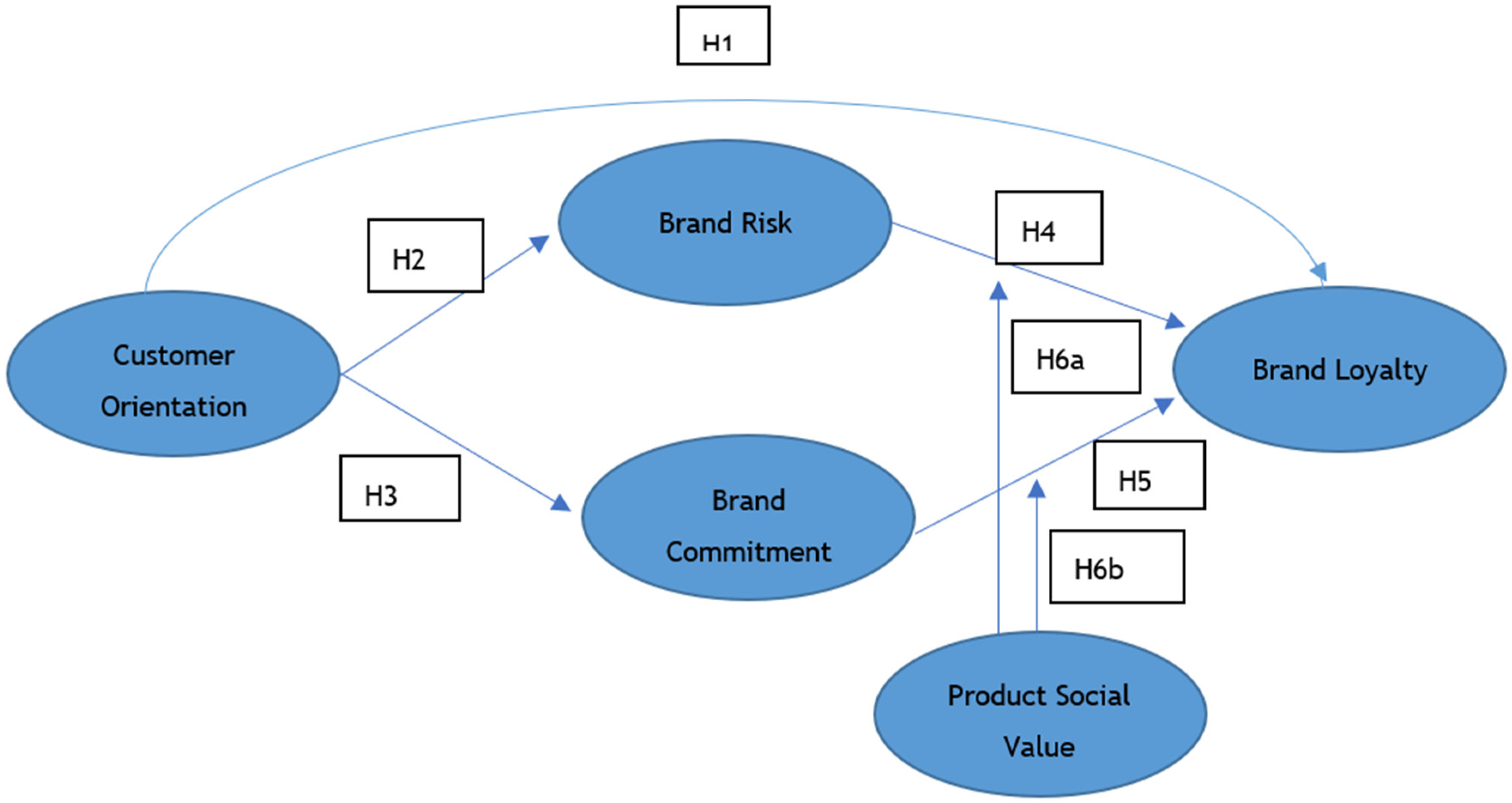

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample

3.2. Scales Used in Model

Psychometric Characteristics of the Scales

4. Analysis and Results

Hypothesis Testing: SEM Analyses

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aguirre-Urreta, Miguel I., and Jiang Hu. 2019. Detecting Common Method Bias: Performance of the Harman’s Single-Factor Test. Data Base Journal 50: 45–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, Icek, and Martin Fishbein. 1972. Attitudes and normative beliefs as factors influencing behavioral intentions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 21: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson and Gerbing. 1988. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin 103: 411–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aurier, Philippe, and Gilles N’Goala. 2010. The differing and mediating roles of trust and relationship commitment in service relationship maintenance and development. Journal of Academic Marketing Science 38: 303–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babakus, Emin, Ugur Yavas, and Osman Karatepe. 2017. Work engagement and turnover intentions: Correlates and customer orientation as a moderator. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 29: 1580–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, Richard, and Youjae Yi. 1988. On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 16: 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaji, Makam S. 2015. Investing in customer loyalty: The moderating role of relational characteristics. Service Business 9: 17–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaji, Sanjit Roy, and Khong Wei. 2016. Does relationship communication matter in B2C service relationships? Journal of Services Marketing 30: 186–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, Rebekah, Charmine Härtel, and Janet McColl-Kennedy. 2005. Experience as a moderator of involvement and satisfaction on brand loyalty in a business-to-business setting. Industrial Marketing Management 34: 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boley, Bynum, EvanJordan, Carol Kline, and Whitney Knollenberg. 2018. Social return and intent to travel. Tourism Management 64: 119–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, Barbara. 2010. Structural Equation Modelling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currás-Pérez, Rafael, Carla Ruiz-Mafé, and Silvia Sanz-Blas. 2013. Social network loyalty: Evaluating the role of attitude, perceived risk and satisfaction. Online Information Review 37: 61–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dariyoush, Jamshidi, and Rousta Alireza. 2021. Brand commitment role in the relationship between brand loyalty and brand satisfaction: Phone industry Malaysia. Journal of Promotion Management 27: 151–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawes, John, and Magda Nenycz-Thiel. 2013. Analysing the intensity of private label competition across retailers. Journal of Business Research 66: 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, Farley, and Fredericj E. Webster, Jr. 1993. Corporate culture, customer orientation, and innovativeness in Japanese firms: A quadrad analysis. Journal of Marketing 57: 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, Grahame, and Richard Staelin. 1994. A model of perceived risk and intended risk-handling activity. Journal of Consumer Research 21: 119–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dursun, Turkan, and Ceyhan Kilic. 2017. Conceptualization and Measurement of Market Orientation: A Review with a Roadmap for Future Research. International Journal of Business and Management 12: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Eckert, Christine, Jordan Louviere, and Towhidul Islam. 2012. Seeing the forest despite the trees: Brand effects on choice uncertainty. International Journal of Research in Marketing 29: 256–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisingerich, Andreas, and Gaia Rubera. 2010. Drivers of brand commitment: A cross-national investigation. Journal of International Marketing 18: 64–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, Martin, and Icek Ajzen. 1974. Attitudes toward objects as predictors of single and multiple behavioral criteria. Psychological Review 81: 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flavián, Carlos, and Miguel Guinalíu. 2006. Consumer trust, perceived security and privacy policy: Three basic elements of loyalty to a web site. Industrial Management & Data Systems 106: 601–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, Claes, and David Larcker. 1981. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research 18: 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, Hong-Youl, and Joby John. 2010. Role of customer orientation in an integrative model of brand loyalty in services. Service Industries Journal 30: 1025–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joseph, Tomas Hult, Christian Ringle, and Marko Sarstedt. 2014. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). Los Angeles: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, Mostafa, and Ahsan Habib. 2017. Corporate life cycle, organizational financial resources and corporate social responsibility. Journal of Contemporary Accounting & Economics 13: 20–36. [Google Scholar]

- Hollebeek, Linda, and Tom Chen. 2014. Exploring positively- versus negatively-valanced brand engagement: A conceptual model. Journal of Product and Brand Management 23: 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homburg, Christian, Michael Müller, and Martin Klarmann. 2011. When should the customer really be king? On the optimum level of salesperson customer orientation in sales encounters. Journal of Marketing 75: 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, Chih-Hui, George Shen, and Pei-Ju Chao. 2015. How does brand misconduct affect the brand–customer relationship? Journal of Business Research 68: 862–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Yu-Jia. 2012. Exploring the relationship between perceived risk and customer involvement, brand equity and customer loyalty as mediators. The International Journal of Organizational Innovation 5: 224–30. [Google Scholar]

- Ismail, Ahmed Rageh. 2017. The influence of perceived social media marketing activities on brand loyalty: The mediation effect of brand and value consciousness. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics 29: 129–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeng, Shih. 2018. Enhancing the creativity of frontline employees: The effects of job complexity and customer orientation. The International Journal of Logistics Management 29: 387–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanten, P., S. Kanten, and M. Baran. 2016. The effect of organizational virtuousness on front line employees’ customer orientation: Role of perceptions. Paper presented at 10th International Congress on Social Sciences Conference Proceedings, Madrid, Spain, September 23–24, vol. 2, pp. 857–74. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Dan J., Donald L. Ferrin, and H. Raghav Rao. 2008. A trust-based consumer decision making model in electronic commerce: The role of trust, perceived risk, and their antecedents. Decision Support Systems 44: 544–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirca, Ahmet, Satish Jayachandran, and William Bearden. 2005. Market orientation: A meta-analytic review and assessment of its antecedents and impact on performance. Journal of Marketing 69: 24–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Jitender, and Vikas Kumar. 2020. Drivers of brand community engagement. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 54: 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai-Ming Tam, Jackie. 2012. The moderating role of perceived risk in loyalty intentions: An investigation in a service context. Marketing Intelligence and Planning 30: 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marakanon, Lalinthorn, and V. Panjakajornsak. 2014. The influence of perceived risks on customer loyalty of environment-friendly electronics products in Thailand. Conference of the International Journal of Arts and Sciences 7: 209–18. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Ruiz, María Pilar, Pablo Ruiz-Palomino, Ricardo Martinez-Canas, and Juan Blazquez-Resino. 2014. Consumer satisfaction and loyalty in private-label food stores. British Food Journal 116: 849–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mick, David Glen, and Claus Buhl. 1992. A meaning-based model of advertising experiences. Journal of Consumer Research 19: 317–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, Sita, Gunjan Malhotra, and Garima Saxena. 2020. In-store marketing of private labels: Applying cue utilization theory. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 49: 145–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narver, John, and Stanley Slater. 1990. The effect of a market orientation on business profitability. Journal of Marketing 54: 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevitt, Jonathan, and Gregory Hancock. 2001. Performance of bootstrapping approaches to model test statistics and parameter standard error estimation in structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling 8: 353–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, Louise, and Charles Jones. 1995. Do rewards really create loyalty? Harvard Business Review 2: 75–82. [Google Scholar]

- Osuagwu, Caroline. 2019. Market Orientation Conceptualizations, Components and Performance-Impacts: A Literature Review and Conceptual Framework. International Journal of Marketing Studies 11: 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Whan, Deborah MacInnis, Joseph Priester, Andreas Eisingerich, and Dawn Iacobucci. 2010. Brand attachment and brand attitude strength: Conceptual and empirical differentiation of two critical brand equity drivers. Journal of Marketing 74: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovici, Dan, Liuchen Guo, and Andrew Fearne. 2022. Perceived Risk and Private Label Purchasing Behavior: An Abstract. In Celebrating the Past and Future of Marketing and Discovery with Social Impact. AMSAC-WC 2021. Developments in Marketing Science: Proceedings of the Academy of Marketing Science. Edited by Juliann Allen, Bruna Jochims and Shuang Wu. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PLMA (Private Label Manufacturers Association). 2017. The Store Brands Story. Scribbr. Available online: https://plma.com/storeBrands/facts2017.html (accessed on 10 July 2021).

- PLMA (Private Label Manufacturers Association. 2020. Private Label Today. Scribbr. Available online: https://www.plmainternational.com/industry-news/private-label-today (accessed on 10 July 2021).

- Podsakoff, Philip, and Dennis Organ. 1986. Self-report in organizational research. Journal of Management 12: 531–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, Philip, Scott MacKenzie, Jeong Lee, and Podsakoff Nathan. 2003. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology 88: 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raju, Sekar, H. Rao Unnava, and Nicole Votolato Montgomery. 2009. The effect of brand commitment on the evaluation of nonpreferred brands: A disconfirmation process. Journal of Consumer Research 35: 851–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, Natalia, Nieves Villaseñor, and Maria Jesús Yagüe. 2017. Creation of consumer loyalty and trust in the retailer through store brands: The moderating effect of choice of store brand name. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 34: 358–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusbult, Caryl, and Buunk Bram. 1993. Commitment processes in close relationships: An interdependence analysis. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 10: 175–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salam, Abdus, Lindsay Ross, and Malcon Beveridge. 2003. A comparison of development opportunities for crab and shrimp aquaculture in southwestern Bangladesh, using GIS modelling. Aquaculture 220: 477–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargeant, Adrian, and Stephen Lee. 2004. Trust and relationship commitment in the United Kingdom voluntary sector: Determinants of donor behavior. Psychology and Marketing 21: 613–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebri, Mouna, and Georges Zaccour. 2017. Cross-country differences in private-label success: An exploratory approach. Journal of Business Research 80: 116–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, Stanley F., and John C. Narver. 1998. Customer-led and market-oriented: Let’s not confuse the two. Strategic Management Journal 19: 1001–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnova, Maria, Vera Rebiazina, and Johanna Frösén. 2018. Customer orientation as a multidimensional construct: Evidence from the Russian markets. Journal of Business Research, Elsevier 86: 457–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, Michael, Gary Bamossy, and Soren Askegaard. 1999. Consumer Bebavior: A European Perspective. Harlow: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, Prashant, and Deborah Owens. 2010. Personality traits and their effect on brand commitment: An empirical investigation. The Marketing Management Journal 20: 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Statt, David. 1997. Understanding the Consumer: A Psycbological Approacb. London: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Steenkamp, Jan-Benedict E. M., and Hans Baumgartner. 2000. On the use of structural equation models for marketing modeling. International Journal of Research in Marketing 17: 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, D. E., C. W. Lamb, and D. L. MacLachlan. 1977. Perceived risk: A synthesis. European Journal of Marketing 11: 312–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton-Brady, Catherine, Tom Taylor, and Patty Kamvounias. 2017. Private label brands: A relationship perspective. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing 32: 10–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuu, Ho Huy, Svein Ottar Olsen, and Pham Thi Thuy Linh. 2011. The moderator effects of perceived risk, objective knowledge and certainty in the satisfaction loyalty relationship. Journal of Consumer Marketing 28: 363–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenberg, Robert J., and Charles E. Lance. 2000. A review and synthesis of the measurement invariance literature: Suggestions, practices, and recommendations for organizational research. Organizational Research Methods 3: 4–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, Valter, Fernando Oliveira Santini, and Clécio Falcao Araújo. 2018. A meta-analytic review of hedonic and utilitarian shopping values. Journal of Consumer Marketing 35: 426–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, Yann, Richard R. Klink, Geoff Simmons, Amir Grinstein, and Mark Palmer. 2017. Branding strategies for high-technology products: The effects of consumer and product innovativeness. Journal of Business Research 70: 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehir, Cemal, Azize Şahin, Hakan Kitapçı, and Mehtap Özşahin. 2011. The effects of brand communication and service quality. In building brand loyalty through brand trust; the empirical research on global brands. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences 24: 1218–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Chuang, Guijun Zhuang, Zhilin Yang, and Yang Zhang. 2017. Brand loyalty versus store loyalty: Consumers’ role in determining dependence structure of supplier–retailer dyads. Journal of Business-to-Business Marketing 24: 136–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Product | Portugal | Spain |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-wrinkle facial cream for women | X | |

| Anti-wrinkle facial cream for men | X | |

| Anti-wrinkle facial cream for women | X | |

| Anti-wrinkle facial cream for men | X | |

| DOC Douro Wine Reserve 2010 | X | |

| DOC Wine 2010 | X |

| Valid Sample | 2900 |

|---|---|

| 35–54 years old | 65.7% |

| Graduate degree or higher | 73.3% |

| Mean | Standard Deviation | Coefficient of Variation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Customer Orientation | 4.25 | 1.305–1.855 | 2.72 |

| Brand Risk | 5.33 | 1.365–1.530 | 2.16 |

| Brand Commitment | 4.43 | 1.712–1770 | 3.06 |

| Brand Loyalty | 4.89 | 1.366–1.965 | 2.57 |

| Customer Orientation | Brand Risk | Brand Commitment | Brand Loyalty | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Customer Orientation | Pearson correlation coefficient | 1 | 0.269 ** | 0.192 ** | 0.650 ** |

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| Brand Risk | Pearson correlation coefficient | 0.269 ** | 1 | 0.603 ** | 0.861 ** |

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| Brand Commitment | Pearson correlation coefficient | 0.192 ** | 0.603 ** | 1 | 0.758 ** |

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| Brand Loyalty | Pearson correlation coefficient | 0.650 ** | 0.861 ** | 0.758 ** | 1 |

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Customer Orientation |

| The Private Label asks its customers about their specific needs |

| The Private Label builds its product/service offerings based on the benefits they generate for their customers |

| The Private Label seeks to know from its customers why they buy their products |

| The Private Label seeks to know why its customers do not choose products of its brand |

| Brand Risk |

| I feel that whatever I bought from the company, it would perform well |

| Brand Commitment |

| I will more likely purchase a brand that is on sale than not |

| Brand Loyalty |

| I intend to buy this brand in the near future |

| I want to buy other products of the Private Label |

| In the category of product, the Private Label brand is my first choice |

| I am willing to pay a higher price to buy Private Label products |

| I will only consider buying Private Label product if the price is low enough |

| I speak positively about the Private Label product |

| I consider the Private Label product to be my first choice in the next few years |

| The Private Label brand offers products that I am looking for |

| I always win when I buy Private Label brand products |

| Customer Orientation | Estimate |

|---|---|

| The Private Label asks its customers about their specific needs | 0.528 |

| The Private Label seeks to provide relevant information to its customers. | 0.722 |

| The Private Label builds its product/service offerings | 0.887 |

| The Private Label adapts its sales policies to the interests of its customers. | 0.903 |

| The main offers of the Private Label seek to respond to the particularities desired by its customers. | 0.848 |

| Brand Risk | |

| I am sure about the Private Label. | 0.962 |

| I know enough to feel comfortable with using the Private Label. | 0.878 |

| Brand Commitment | 0.953 |

| If the Private Label were not available at the store, it would make little difference to me if I had to choose another brand. | 0.804 |

| I can see myself as being loyal to the Private Label. | 0.964 |

| Brand Loyalty | |

| I recommend Private Label product whenever they ask for my opinion | 0.846 |

| The publicity I see on competing brands of Private Label product does not change my purchasing decision. | 0.872 |

| I will continue to be a loyal customer of Private Label product. | 0.764 |

| Next time I buy the product, I will buy from the Private Label brand. | 0.871 |

| I intend to recommend the Private Label product to other people/friends; | 0.858 |

| MODEL FIT SUMMARY | |

| Chi-square = 11,999; df = 66; p = 0.000 CFI = 0.979; IFI = 0.979; TLI = 0.971 RMSEA = 0.062; LO = 0.058; HI = 0.065 |

| CR | AVE | Brand Commitment | Customer Orientation | Brand Risk | Brand Loyalty | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brand Commitment | 0.880 | 0.788 | 0.888 | |||

| Customer Orientation | 0.889 | 0.624 | 0.188 | 0.790 | ||

| Brand Risk | 0.918 | 0.848 | 0.591 | 0.262 | 0.921 | |

| Brand Loyalty | 0.925 | 0.711 | 0.763 | 0.242 | 0.855 | 0.843 |

| CI | |

|---|---|

| CO-BRISK | 0.084–0.120 |

| CO-BCOM | 0.060–0.096 |

| CO-BLOY | 0.077–0.113 |

| BRISK-BLOY | 0.144–0.164 |

| BCOM-BLOY | 0.134–0.158 |

| Chi-Square | |

|---|---|

| Without mediation | 4271.008 df = 804 |

| Partial mediation | 2605.183 df = 795 |

| Total mediation | 2597.020 df = 792 |

| Hypothesis | Relationships | Standardized Regression Weights | Test | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | CO-LOY | −0.074 | Not Supported | 0.551–0.895 |

| H1 Indirect effects | CO-LOY INDIRECT | 0.723 *** | Supported | |

| H2 | CO-RISK | 0.649 *** | Supported | 0.573–0.961 |

| H4 | RISK-LOY | 0.587 *** | Supported | 0.540–0.900 |

| H3 | CO-COM | 0.539 *** | Supported | 0.521–0.953 |

| H5 | COM-LOY | 0.472 *** | Supported | 0.395–0.607 |

| MODEL FIT SUMMARY | ||||

| Chi-square = 3176, df = 789 CFI = 0.917; IFI = 0.917; TLI = 0.905; NFI = 0.884 RMSEA = 0.050 | ||||

| HYP | Relationships | Standardized Regression Weights Cream | Standardized Regression Weights Wine | Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H6a | Moderate category RISK-LOY | 0.727 | 0.664 | Supported p = 0.000 |

| H6b | Moderate category COM-LOY | 0.541 | 0.461 | Supported p = 0.000 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Serra, E.; de Magalhães, M.; Silva, R.; Meirinhos, G. How Market Orientation Impacts Customer’s Brand Loyalty and Buying Decisions. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2022, 15, 357. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm15080357

Serra E, de Magalhães M, Silva R, Meirinhos G. How Market Orientation Impacts Customer’s Brand Loyalty and Buying Decisions. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2022; 15(8):357. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm15080357

Chicago/Turabian StyleSerra, Elizabeth, Mariana de Magalhães, Rui Silva, and Galvão Meirinhos. 2022. "How Market Orientation Impacts Customer’s Brand Loyalty and Buying Decisions" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 15, no. 8: 357. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm15080357

APA StyleSerra, E., de Magalhães, M., Silva, R., & Meirinhos, G. (2022). How Market Orientation Impacts Customer’s Brand Loyalty and Buying Decisions. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 15(8), 357. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm15080357