RETRACTED: The Relationship between CEO Psychological Biases, Corporate Governance and Corporate Social Responsibility

Abstract

:1. Introduction

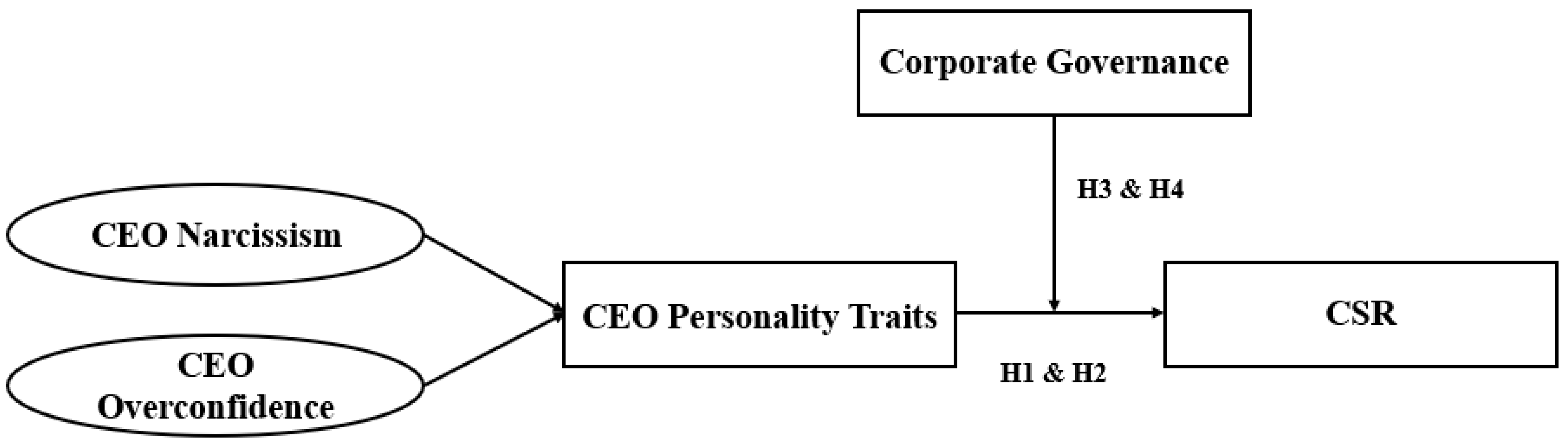

2. Theoretical Framework

3. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

3.1. CEO Narcissism and CSR Activities

3.2. CEO Overconfidence and CSR Activities

3.3. The Moderating Effect of Corporate Governance Mechanisms on the CEO’s Personality Traits—CSR Activities Relationship

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Sample Selection, Data Collection and Empirical Model

4.2. Measurement: Corporate Social Responsibility Measure (CSR)

4.2.1. CEO Narcissism Measure (NARC)

4.2.2. CEO Overconfidence Measure (OVC)

4.2.3. Corporate Governance Measure (CGS)

4.2.4. Control Variables Measures

5. Empirical Analysis and Results Discussion

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

5.2. Tests on Panel Data

5.3. Hypotheses Validation

5.4. Robustness Check

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abatecola, Gianpaolo, Andrea Caputo, and Matteo Cristofaro. 2018. Reviewing Cognitive Distortions in Managerial Decision Making. Toward an Integrative Co-Evolutionary Framework. Journal of Management Development 37: 409–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, Ruth V., Deborah E. Rupp, Cynthia A. Williams, and Jyoti Ganapathi. 2007. Putting the S back in corporate social responsibility: A multilevel theory of social change in organizations. Academy of Management Review 32: 836–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajaz, Aiman, Zhou Shenbei, and Muddassar Sarfraz. 2020. Delineating the Influence of Boardroom’s Gender Diversity on Corporate Social Responsibility, Firm’s Financial Performance, and Reputation. LogForum 16: 61–74. [Google Scholar]

- Aktas, Nihat, Eric Bodt, Helen Bollaert, and Richard Roll. 2016. CEO Narcissism and the Takeover Process: From Private Initiation to Deal Completion. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 51: 113–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, Zinat S., Mark A. Chen, Conrad S. Ciccotello, and Harley E. Ryan. 2018. Board structure mandates: Consequences for director location and financial reporting. Management Science 64: 4735–54. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Shammari, Marwan, A. Rasheed, and Hussam A. Al-Shammari. 2019. CEO narcissism and corporate social responsibility: Does CEO narcissism affect CSR focus? Journal of Business Research 104: 106–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreou, Panayiotis C., John A. Doukas, Demetris Koursaros, and Christodoulos Louca. 2019. Valuation effects of overconfident CEOs on corporate diversification and refocusing decisions. Journal of Banking & Finance 100: 182–204. [Google Scholar]

- Balestra, Pietro. 1992. Fixed Effect Models and Fixed Coefficient Models. In The Econometrics of Panel Data. Advanced Studies in Theoretical and Applied Econometrics. Edited by L. Mátyás and P. Sevestre. Dordrecht: Springer, vol. 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltratti, Andrea. 2005. The complementarily between corporate governance and corporate social responsibility. Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance 30: 373–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Mohamed, Ezzeddine, and Mohammed A. Shehata. 2017. R&D investment–cash flow sensitivity under managerial optimism. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance 14: 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Mohamed, Ezzeddine, Amel Baccar, and Abdelfatteh Bouri. 2013. Investment Cash Flow Sensitivity and Managerial Optimism: A Literature Review Via the Classification Scheme Technique. Review of Finance and Banking 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogart, Laura M., Eric G. Benotsch, and Jelena D. Pavlovic. 2004. Feeling superior but threatened: The relation of narcissism to social comparison. Basic and Applied Social Psychology 26: 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyl, Tine, Christophe Boone, and James B. Wade. 2019. CEO narcissism, risk-taking, and resilience: An empirical analysis in US commercial banks. Journal of Management 45: 1372–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, Nuria, and Flora Calvo. 2018. Corporate Social Responsibility and Multiple Agency Theory: A case study of internal stakeholder engagement. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 25: 1223–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capalbo, Francesco, Alex Frino, Ming Ying Lim, Vito Mollica, and Riccardo Palumbo. 2018. The impact of CEO narcissism on earnings management. Abacus 54: 210–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Chen Shan, Shang Wu Yu, and Cheng Huang Hung. 2015. Firm risk and performance: The role of corporate governance. Review of Managerial Science 9: 141–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, Arijit, and Donald C. Hambrick. 2007. It’s all about me: Narcissistic CEOs and their effects on company strategy and performance. Administrative Science Quarterly 52: 351–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, Arijit, and Donald C. Hambrick. 2011. Executive personality, capability cues, and risk taking: How Narcissistic CEOs react to their successes and stumbles. Administrative Science Quarterly 56: 202–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, Arijit, and Timothy G. Pollock. 2017. Master of puppets: How narcissistic CEOs construct their professional worlds. Academy of Management Review 42: 703–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, Richa. 2017. Corporate social responsibility and employee engagement: Can CSR help in redressing the engagement gap? Social Responsibility Journal 13: 323–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Jie, Woon Sau Leung, Wei Song, and Marc Goergen. 2019. Why female board representation matters: The role of female directors in reducing male CEO overconfidence. Journal of Empirical Finance 53: 70–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chih, Hsiang Lin, Hsiang Hsuan Chih, and Tzu Yin Chen. 2010. On the Determinants of Corporate Social Responsibility: International Evidence on the Financial Industry. Journal of Business Ethics 93: 115–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Sang Jun, Chune Young Chung, and Jason Young. 2019. Study on the Relationship between CSR and Financial Performance. Sustainability 11: 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Jun Hyeok, Saerona Kim, and Ayoung Lee. 2020. CEO Tenure, Corporate Social Performance, and Corporate Governance: A Korean Study. Sustainability 12: 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Paul Moon Sub, Chune Young Chung, and Chang Liu. 2018. Self-attribution of overconfident CEOs and asymmetric investment-cash flow sensitivity. The North American Journal of Economics and Finance 46: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chyz, James A., Fabio B. Gaertner, Asad Kausar, and Luke Watson. 2019. Overconfidence and corporate tax policy. Review of Accounting Studies 24: 1114–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission of the European Communities. 2001. A Sustainable Europe for a Better World: A European Union Strategy for Sustainable Development. Luxembourg: Commission of the European Communities. [Google Scholar]

- Cycyota, Cynthia S., and David A. Harrison. 2006. What (not) to expect when surveying executives: A meta-analys is of top manager response rates and techniques over time. Organizational Research Methods 9: 133–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, Manfred FR Kets, and Danny Miller. 1985. Narcissism and leadership: An object relations perspective. Human Relations 38: 583–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giuli, Alberta, and Leonard Kostovetsky. 2014. Are red or blue companies more likely to go green? Politics and corporate social responsibility. Journal of Financial Economics 111: 158–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Shuili, and Sankar Sen. 2016. Challenging Competition with CSR: Going Beyond the Marketing Mix to Make a Difference. GfK Marketing Intelligence Review 8: 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ghoul, Sadok, Omrane Guedhami, and Yongtae Kim. 2017. Country-level institutions, firm value, and the role of corporate social responsibility initiatives. Journal of International Business Studies 48: 360–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Guindy, Medhat N., and Mohamed A. Basuony. 2018. Audit Firm Tenure and Earnings Management: The Impact Of Changing Accounting Standards In UK Firms. The Journal of Developing Areas 52: 167–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelen, Andreas, Christoph Neumann, and Susanne Schmidt. 2016. Should entrepreneurially oriented firms have narcissistic CEOs? Journal of Management 42: 698–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernawan, Kadek, and Debby Ratna Daniel. 2019. The Influence of CEO Narcissism on Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure. Journal Akuntansi 23: 253–68. [Google Scholar]

- Fama, Eugene F., and Kenneth R. French. 1997. Industry costs of equity. Journal of Financial Economics 43: 153–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrero, Ferrero Idoya, F. Angeles Izquierdo, and María Jesús Torres. 2015. Integrating sustainability into corporate governance: An empirical study on board diversity. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 22: 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, Francis J., and Barry M. Staw. 2004. Lend me your wallets: The effect of charismatic leadership on external support for an organization. Strategic Management Journal 25: 309–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, Robert Edward. 1984. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach. Boston: Pi Iman. [Google Scholar]

- Fung, Hung Gay, Penghua Qiao, Jot Yau, and Yuping Zeng. 2020. Leader narcissism and outward foreign direct investment: Evidence from Chinese firms. International Business Review 29: 101–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giroud, Xavier, and Holger M. Mueller. 2017. Firm leverage, consumer demand, and employment losses during the Great Recession. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 132: 271–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godos-Díez, José-Luis, L. Cabeza-García, Daniel Alonso-Martínez, and Roberto Fernández-Gago. 2018. Factors influencing board of directors’ decision-making process as determinants of CSR engagement. Review of Managerial Science 12: 229–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, Anand M., and Anjan V. Thakor. 2008. Overconfidence, CEO selection, and corporate governance. The Journal of Finance 63: 2737–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gond, Jean-Pascal, A. El Akremi, Valrie Swaen, and Nishat Babu. 2017. The psychological micro foundations of corporate social responsibility: A person-centric systematic review. Journal of Organizational Behavior 38: 225–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grijalva, Emily, and Peter D. Harms. 2014. Narcissism: An integrative synthesis and dominance complementarity model. The Academy of Management Perspectives 28: 108–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambrick, Donald C., and Phyllis A. Mason. 1984. Upper echelons: The organization as a reflection of its top managers. Academy of Management Review 9: 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, Kerri. 2005. Employee engagement partnerships: Can they contribute to the development of an integrated CSR culture. Partnership Matters: Current Issues in Cross-Sector Collaboration 3: 17–20. [Google Scholar]

- Harms, Peter D., Seth M. Spain, and Sean T. Hannah. 2011. Leader development and the dark side of personality. Leadership Quarterly 22: 495–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaton, James B. 2002. Managerial optimism and corporate finance. Financial Management 31: 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaton, James B., Simon Gervais, and Terrance Odean. 2011. Overconfidence, Compensation Contracts, and Capital Budgeting. The Journal of Finance 66: 1735–77. [Google Scholar]

- Hiebl, Martin. R. 2014. Upper echelons theory in management accounting and control research. Journal of Management Control 24: 223–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirshleifer, David, Angie Low, and Siew Hong Teoh. 2012. Are Overconfident CEOs Better Innovators? The Journal of Finance 67: 1457–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Chi-Kun. 2005. Corporate governance and corporate competitiveness: An international analysis. Corporate Governance: An International Review 13: 211–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hribar, Paul, and Holly Yang. 2016. CEO overconfidence and management forecasting. Contemporary Accounting Research 33: 204–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Ying Sophie, and Mengyu Li. 2019. Are overconfident executives alike? overconfident executives and compensation structure: Evidence from China. The North American Journal of Economics and Finance 48: 434–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikram, Atif, Zhichuan Frank Li, and Dylan Minor. 2019. CSR-contingent executive compensation contracts. Journal of Banking & Finance, 105–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, Ioannis, and Geogre Serafeim. 2012. What drives corporate social performance? The role of nation-level institutions. Journal of International Business Studies 43: 834–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, Dima, Mona Zanhour, and Tamar Keshishian. 2008. Peculiar strengths and relational attributes of SMEs in the context of CSR. Journal of Business Ethics 87: 355–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, Ming, and Kin-Wai Lee. 2015. CEO compensation and corporate social responsibility. Journal of Multinational Financial Management 29: 46–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiraporn, Pornsit, and Pandej Chintrakarn. 2013. How do powerful CEOs view corporate social responsibility (CSR)? An empirical note. Economics Letters 119: 344–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, Hoje, and Maretno A. Harjoto. 2012. The causal effect of corporate governance on corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics 106: 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, Nigel. 1999. Good Corporate Governance. London: Accountants Digest. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Bora, Seoki Lee, and Kyung Ho Kang. 2018. The moderating role of CEO narcissism on the relationship between uncertainty avoidance and CSR. Tourism Management 67: 203–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koellinger, Philipp, Maria Minniti, and Christian Schade. 2007. I think I can, I think I can”: Overconfidence and entrepreneurial behavior. Journal of Economic Psychology 28: 502–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konrath, Sara, Brain P. Meier, and Brad J. Bushman. 2014. Development and validation of the single item narcissism scale (SINS). PLoS ONE 9: e103469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouaib, Amel, and Anis Jarboui. 2016. The moderating effect of CEO profile on the link between cutting R&D expenditures and targeting to meet/beat earnings benchmarks. The Journal of High Technology Management Research 27: 140–60. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Jin-Ping, Edward M. Lin, James Juichia Lin, and Yang Zhao. 2019. Bank systemic risk and CEO overconfidence. The North American Journal of Economics and Finance. forthcoming. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, Ben W., and Judith L. Walls. 2014. Difference in degrees: CEO characteristics and firm environmental disclosure. Strategic Management Journal 35: 712–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Jialong, Zulfiquer Ali Haider, Xianzhe Jin, and Wenlong Yuan. 2019. Corporate controversy, social responsibility and market performance: International evidence. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money 60: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Fengyi, Sheng-Wei Lin, and Wen Chang Fang. 2019. How CEO narcissism affects earnings management behaviors. The North American Journal of Economics and Finance. forthcoming. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindblom, C. K. 1983. The Concept of Organizational Legitimacy and its Implications for Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure. American Accounting Association Public Interest Section, 220–21. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Xueming, Heli Wang, Sascha Raithel, and Qinglin Zheng. 2015. Corporate social performance, analyst stock recommendations, and firm future returns. Strategic Management Journal 36: 123–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmendier, Ulrike, and Geoffrey Tate. 2005. CEO overconfidence and corporate investment. The Journal of Finance 60: 2661–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmendier, Ulrike, and Geoffrey Tate. 2008. Who makes acquisitions? CEO overconfidence and the market’s reaction. Journal of Financial Economics 89: 20–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmendier, Ulrike, Geoffrey Tate, and Jon Yan. 2011. Overconfidence and early-life experiences: The effect of managerial traits on corporate financial policies. The Journal of Finance 66: 1687–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manner, Mikko H. 2010. The impact of CEO characteristics on corporate social performance. Journal of Business Ethics 93: 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolis, Joshua D., and James P. Walsh. 2003. Misery loves companies: Rethinking social initiatives by business. Administrative Science Quarterly 48: 268–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsiglia, Emanuele, and Isabella Falautano. 2005. Corporate social responsibility and sustainability challenges for a Bancassurance Company. The Geneva Papers 30: 485–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, Scott, Barry Oliver, and Sizhe Song. 2017. Corporate social responsibility and CEO confidence. Journal of Banking and Finance 75: 280–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, Abagail, and Donald Siegel. 2001. Corporate social responsibility: A theory of the firm perspective. Academy of Management Review 26: 117–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Danny, Manfred F. R. Kets De Vries, and Jean-Marie Toulouse. 1982. Top Executive Locus of Control and Its Relationship to Strategy-Making, Structure, and Environment. The Academy of Management Journal 25: 237–53. [Google Scholar]

- Misangyi, Vilmos F., and Abhijith G. Acharya. 2014. Substitutes or complements? A configurational examination of corporate governance mechanisms. Academy of Management Journal 57: 1681–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muttakin, Mohammad Badrul, Arifur Khan, and Dessalegn Getie Mihret. 2017. Business group affiliation, earnings management and audit quality: Evidence from Bangladesh. Managerial Auditing Journal 32: 427–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nour, Abdulnaser Ibrahim, Abdel-Aziz Ahmad Sharabati, and Khitam Mahmoud Hammad. 2020. Corporate Governance and Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure. International Journal of Sustainable Entrepreneurship and Corporate Social Responsibility (IJSECSR) 5: 20–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, Charles A., III, and Bernadette Doerr. 2020. Conceit and deceit: Lying, cheating, and stealing among grandiose narcissists. Personality and Individual Differences 154: 109–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oesterle, Michael-Jörg, Corinna Elosge, and Lukas Elosge. 2016. Me, myself and I: The role of CEO narcissism in internationalization decisions. International Business Review 25: 1114–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Kyung-Hee, Jinho Byun, and Paul Moon Sub Choi. 2020. Managerial Overconfidence, Corporate Social Responsibility Activities, and Financial Constraints. Sustainability 12: 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peni, Emilia. 2014. CEO and chairperson characteristics and firm performance. Journal of Management and Governance 18: 185–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrenko, Oleg V., Federico Aime, Jason Ridge, and Aaron Hill. 2016. Corporate social responsibility or CEO narcissism? CSR motivations and organizational performance. Strategic Management Journal 37: 262–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prior, Helmut, Ariane Schwarz, and Onur Güntürkün. 2008. Mirror-induced behavior in the magpie (Pica pica): Evidence of self-recognition. PLoS Biology 6: e202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raskin, Robert, and Howard Terry. 1988. A principal-components analysis of the narcissistic personality inventory and further evidence of its construct validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 54: 890–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saridakis, Charalampos, Sofia Angelidou, and Arch G. Woodside. 2020. What type of CSR engagement suits my firm best? Evidence from an abductively-derived typology. Journal of Business Research 108: 174–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauerwald, Steve, and Weichieh Su. 2019. CEO Overconfidence and CSR Decoupling (July 2019). Corporate Governance: An International Review 27: 283–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrand, Catherine, and Sarah Zechman. 2012. Executive overconfidence and the slippery slope to financial misreporting. Journal of Accounting and Economics 53: 311–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Yi, Cuili Qian, Guoli Chen, and Rui Shen. 2015. How CEO hubris affects corporate social (ir)responsibility: CEO hubris and CSR. Strategic Management Journal 36: 1338–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetrault Sirsly, Carol-Ann, and Elena Lvina. 2019. From doing good to looking even better: The dynamics of CSR and reputation. Business & Society 58: 1234–66. [Google Scholar]

- Tirole, Jean. 2001. Corporate governance. Econometrica 69: 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccaro, Annemarie, Ezekiel W. Kimball, Adam M. Moore, Barbara M. Newman, and Peter F. Troiano. 2018. College students with disabilities narrating an emerging sense of purpose: A grounded theory model. Journal of College Student Development 59: 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Berghe, Lutgrat, and Celine Louche. 2005. The link between corporate governance and corporate social responsibility in insurance. The Geneva Papers 30: 425–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Linden, Sander, and Seth A. Rosenthal. 2016. Measuring narcissism with a single question? A replication and extension of the Single-Item Narcissism Scale (SINS). Personality and Individual Differences 90: 238–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddock, Sandra. 2004. Parallel universes: Companies, academics and the progress of corporate citizenship. Business and Society Review 109: 5–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldman, David, and Donald Siegel. 2008. Defining the socially responsible leader. Leadership Quarterly 19: 117–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, Harry M., and Roy F. Baumeister. 2002. The performance of narcissists rises and falls with perceived opportunity for glory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 82: 819–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Heli, and Jaepil Choi. 2013. A new-look at the corporate social-financial performance relationship: The moderating roles of temporal and interdomain consistency in corporate social performance. Journal of Management 39: 416–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windsor, Duane, and Lee Preston. 1988. Corporate Governance, Social Policy and Social Performance in the Multinational Corporation. Research in Corporate Social Performance and Policy 10: 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Zahid, Muhammad, Haseeb Ur Rahman, Wajahat Ali, Musa Khan, Majed Alharthi, Muhammad Imran Qureshi, and Amin Jan. 2020. Boardroom Gender Diversity: Implications for Corporate Sustainability Disclosures in Malaysia. Journal of Cleaner Production 224: 118683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Country | Firms | % |

|---|---|---|

| Belgium | 40 | 9 |

| France | 50 | 12 |

| Germany | 70 | 17 |

| Norway | 30 | 7 |

| Spain | 30 | 7 |

| Sweden | 70 | 17 |

| Switzerland | 30 | 7 |

| United Kingdom | 100 | 24 |

| Total | 420 | 100 |

| Measure | Description | Data Source | Authors |

|---|---|---|---|

| NPI | Four dimensions of the NPI assess narcissism: exploitability/entitlement, leadership/authority, superiority/arrogance, and self-absorption/self-admiration | Survey | Raskin and Terry (1988), Capalbo et al. (2018), Ernawan and Daniel (2019), O’Reilly and Doerr (2020). |

| 8 adjectives | It contains eight adjectives representing narcissism (arrogant, assertive, boastful, conceited, egotistical, self-centered, show-off, and temperamental). To shape a scale, the eight items must be averaged. | Survey | Jamali et al. (2008), O’Reilly and Doerr (2020). |

| SINS | The Single-Item Narcissism Scale (SINS) compared with other longer scales and the more pathological aspects of narcissism were taken into account. The question to answer by the respondents is: “To what degree do you agree with the argument ‘I am a narcissist’”? (1 = not so real, 7 = very real). | Survey | Konrath et al. (2014), Vander Van der Linden and Rosenthal (2016), O’Reilly and Doerr (2020). |

| Narcissism Score 1 | The ratio of singular first-person pronouns (me, me, my, myself to total first-person pronouns (me, me, my, me-myself, we, us, our, our, ourselves). | Annual report and Newspapers. | Kendall (1999), Aktas et al. (2016), Capalbo et al. (2018). |

| Narcissism Score 2 | (a) prominence of the CEO’s photograph on a 4-point scale in the company’s annual report; (b) prominence of the CEO in press releases as the number of occasions the CEO was named in the company’s pressreleases, divided by the number of times the other top executives of the company were named; (c) the proportional cash pay by dividing the cash compensation of the CEO by that of the company’s second highest paying executive; (d) the CEO’s equity rewards and stock options is the relative non-cash compensation split by the second highest paid executive. | Annual report and Bloomberg database | Chatterjee and Hambrick (2007), Oesterle et al. (2016), Tang et al. (2015), Al-Shammari et al. (2019) |

| Measure | Description | Authors |

|---|---|---|

| Press | Comparing the number of articles that use the confident terms and the number of articles that use the cautious terms. | Malmendier and Tate (2005, 2008), Hirshleifer et al. (2012), Hribar and Yang (2016). |

| Stock options | In two or more of the sample years, the proxy for CEO overconfidence is equivalent to one when a CEO retains at least 67 percent of the total optional remuneration and zero otherwise. | Hirshleifer et al. (2012), Lee et al. (2019). |

| Prior Performance | Previous output equals to thepre-tax operating cash flow returns adjusted in a given year divided by the previous year’s market value of assets. | Fama and French (1997), Koellinger et al. (2007), P. M. S. Choi et al. (2018). |

| Score | (a) Industry-adjusted excess investment; (b) Industry-adjusted net dollars of acquisitions made by the firm; (c) Industry-adjusted debt to equity ratio; (d) Dividend policy. | Schrand and Zechman (2012), Ben Mohamed et al. (2013), Kouaib and Jarboui (2016). |

| Variable | Mean | Min | Median | Max | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSR | 78.12 | 7.76 | 85.43 | 95.78 | 18.48 |

| CGS | 70.16 | 1.81 | 75.48 | 97.07 | 21.67 |

| NARC | 0.09 | −1.00 | 0.33 | 1.00 | 0.57 |

| OVC | 0.74 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.43 |

| SIZE | 6.90 | 5.19 | 6.84 | 8.47 | 0.58 |

| AGE | 74.09 | 1.00 | 52.00 | 293.00 | 59.37 |

| ROA | 10.00 | −4.19 | 7.71 | 69.32 | 9.01 |

| LEV | 24.52 | 0.00 | 24.22 | 80.36 | 14.78 |

| RD | 4.49 | 0.01 | 1.95 | 149.56 | 9.20 |

| CSR | CGS | NARC | OVC | SIZE | AGE | ROA | LEV | RD | VIF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSR | 1 | |||||||||

| CGS | 0.22 *** | 1 | 1.06 | |||||||

| NARC | 0.02 | 0.09 *** | 1 | 1.05 | ||||||

| OVC | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.05 * | 1 | 1.83 | |||||

| SIZE | 0.57 *** | 0.08 *** | −0.04 | 0.01 | 1 | 1.34 | ||||

| AGE | 0.16 *** | −0.01 | 0.06 ** | −0.03 | 0.05 ** | 1 | 1.08 | |||

| ROA | −0.04 | 0.04 | −0.02 | 0.07 ** | −0.15 *** | −0.09 *** | 1 | 1.14 | ||

| LEV | 0.12 *** | 0.08 *** | −0.08 | −0.01 | 0.29 *** | −0.06 ** | −0.19 *** | 1 | 1.18 | |

| RD | −0.20 *** | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.06 ** | −0.21 *** | −0.13 *** | 0.09 *** | −0.17 *** | 1 | 1.10 |

| Panel A: Model 1 | Panel B: Model 2 | Panel C: Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | t-Value | Coef. | t-Value | Coef. | t-Value | |

| Constant | −3.88 *** | −2.00 | −4.27 *** | −2.01 | −3.67 *** | −3.23 |

| CGS | 0.11 *** | 3.48 | 0.11 *** | 3.13 | ||

| NARC | 0.15 *** | 3.49 | 0.37 *** | 3.27 | ||

| NARC × CGS | −0.24 *** | −3.68 | ||||

| OVC | 0.18 *** | 2.76 | 0.31 * | 1.80 | ||

| OVC × CGS | 0.21 ** | 2.47 | ||||

| SIZE | 0.16 *** | 4.82 | 0.13 *** | 4.09 | 0.16 *** | 4.16 |

| AGE | 0.03 *** | 3.76 | 0.02 *** | 3.96 | 0.04 *** | 3.10 |

| ROA | 0.08 *** | 4.12 | 0.06 *** | 2.91 | 0.05 *** | 2.60 |

| LEV | −0.06 *** | −4.01 | −0.07 *** | −4.89 | −0.09 *** | −4.55 |

| RD | −0.30 * | −1.90 | −0.19 ** | −2.59 | −0.34 *** | −3.95 |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| Country FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| Hausman’s test | 29.98 *** (0.000) | 31.47 *** (0.000) | 33.28 *** (0.000) | |||

| Breusch–Pagan test | 98.74 *** (0.000) | 94.53 *** (0.000) | 87.96 *** (0.000) | |||

| Wooldridge test | 0.69 ** (2.38) | 0.57 ** (2.43) | 0.72 ** (2.26) | |||

| R-squared | 0.34 | 0.39 | 0.38 | |||

| Panel A: Model 1 | Panel B: Model 2 | Panel C: Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | t-Value | Coef. | t-Value | Coef. | t-Value | |

| Constant | −4.05 *** | −3.23 | −3.53 *** | −4.26 | −5.96 *** | −4.96 |

| CGS | 0.12 *** | 6.28 | 0.26 *** | 3.39 | ||

| NARC | 0.11 *** | 3.75 | 0.49 *** | 4.86 | ||

| NARC × CGS | −0.19 *** | −3.83 | ||||

| OVC | 0.48 *** | 3.23 | 0.28 ** | 2.53 | ||

| OVC × CGS | 0.17 *** | 3.10 | ||||

| SIZE | 0.36 *** | 6.81 | 0.33 *** | 6.09 | 0.27 *** | 5.88 |

| AGE | 0.05 *** | 2.98 | 0.04 | 0.98 | 0.01 | 0.52 |

| ROA | 0.02 *** | 2.89 | 0.01 | 0.27 | 0.01 | 0.98 |

| LEV | −0.07 | −1.24 | −0.10 * | −1.91 | −0.05 | −0.48 |

| RD | 0.18 | 1.23 | 0.09 * | 1.84 | 0.16 ** | 2.17 |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| Country FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| R-squared | 0.40 | 0.38 | 0.29 | |||

| Panel A: Model 1 | Panel B: Model 2 | Panel C: Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | t-Value | Coef. | t-Value | Coef. | t-Value | |

| Constant | −4.67 *** | −3.08 | −2.65 *** | −2.67 | −3.41 *** | −3.27 |

| CGS | 0.12 *** | 3.44 | 0.16 *** | 2.94 | ||

| NARC | 0.17 ** | 2.44 | 0.49 *** | 3.62 | ||

| NARC × CGS | −0.22 *** | −2.83 | ||||

| OVC | 0.58 *** | 2.85 | 2.00 ** | 2.47 | ||

| OVC × CGS | 0.05 ** | 2.35 | ||||

| SIZE | 0.17 *** | 5.09 | 0.29 *** | 4.35 | 0.63 *** | 6.73 |

| AGE | 0.07 * | 1.98 | 0.04 * | 1.84 | 0.02 ** | 2.29 |

| ROA | 0.04 *** | 2.91 | 0.02 ** | 2.54 | 0.07 ** | 2.40 |

| LEV | −0.09 *** | −3.15 | −0.08 *** | −3.27 | −0.11 *** | −3.50 |

| RD | 0.14 ** | 2.20 | 0.14 ** | 2.33 | 0.17 ** | 2.15 |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| Country FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| R-squared | 0.44 | 0.37 | 0.31 | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Salhi, B. RETRACTED: The Relationship between CEO Psychological Biases, Corporate Governance and Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2021, 14, 317. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14070317

Salhi B. RETRACTED: The Relationship between CEO Psychological Biases, Corporate Governance and Corporate Social Responsibility. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2021; 14(7):317. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14070317

Chicago/Turabian StyleSalhi, Bassem. 2021. "RETRACTED: The Relationship between CEO Psychological Biases, Corporate Governance and Corporate Social Responsibility" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 14, no. 7: 317. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14070317

APA StyleSalhi, B. (2021). RETRACTED: The Relationship between CEO Psychological Biases, Corporate Governance and Corporate Social Responsibility. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 14(7), 317. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14070317