Abstract

An important step towards COVID-19 pandemic control is adequate knowledge and adherence to mitigation measures, including vaccination. We assessed the level of COVID-19 knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) among residents from an urban informal settlement in the City of Nairobi (Kibera), and a rural community in western Kenya (Asembo). A cross-sectional survey was implemented from April to May 2021 among randomly selected adult residents from a population-based infectious diseases surveillance (PBIDS) cohort in Nairobi and Siaya Counties. KAP questions were adopted from previous studies. Factors associated with the level of COVID-19 KAP, were assessed using multivariable regression methods. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance was 83.6% for the participants from Asembo and 59.8% in Kibera. The reasons cited for vaccine hesitancy in Kibera were safety concerns (34%), insufficient information available to decide (18%), and a lack of belief in the vaccine (21%), while the reasons in Asembo were safety concerns (55%), insufficient information to decide (26%) and lack of belief in the vaccine (11%). Our study findings suggest the need for continued public education to enhance COVID-19 knowledge, attitudes, and practices to ensure adherence to mitigation measures. Urban informal settlements require targeted messaging to improve vaccine awareness, acceptability, and uptake.

Keywords:

urban; rural; COVID-19; knowledge; attitudes; practices; vaccine acceptability; vaccine hesitancy; Kenya 1. Introduction

Since the first case of Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was confirmed in Kenya on 13 March 2020, the number of cases and deaths has risen steadily. As of 2 September 2022, more than 600 million cases and 6 million deaths had been reported worldwide, including 338,210 cases and 5674 deaths in Kenya [1]. COVID-19 in Africa has been characterized by a series of waves dominated by particular variants of SARS-CoV-2 [2,3]. The elderly and those with underlying medical conditions are at a greater risk of developing severe illness and possible death after infection with COVID-19 [4]. To control COVID-19, the Kenyan government introduced measures such as suspension of international travel, restriction of movements in hotspot areas, closure of all learning institutions, and banning public gatherings [5]. The government also encouraged the wearing of face masks in public, frequent hand hygiene practices, and keeping physical distance.

Just like Kenya, many African countries imposed partial or total lockdowns on peoples’ movements and activities, with detrimental impacts on the economies [6]. Some countries adopted their own models of mitigating COVID-19 based on country-specific culture and socioeconomic activities [7]. The effectiveness of any COVID-19 mitigation measures depends on widespread acceptance and uptake by the population [8]. There has been increased availability of COVID-19 vaccines since they became available globally in November 2020. Countries initially set a target to vaccinate 60–80% of the population to achieve herd immunity [9]. There are concerns that emerging variants of SARS-CoV-2 might push the overall herd immunity threshold to >80% [10]. The Kenyan government rolled out vaccination against COVID-19 in March 2021, one year after the first case was confirmed in the country. At the time of the study, only the Astra Zeneca-Oxford COVID-19 vaccine was in use in the country [11]. Initially, priority was given to frontline healthcare workers but six months later, this was expanded to include the elderly (≥58 years), those with underlying chronic conditions and other frontline workers, such as teachers and the military [11,12]. As of 1 September 2022, 9.4 million persons had been fully vaccinated in Kenya with 2.2 million persons having received only the first dose [12].

To effectively control the pandemic, at least 70–90% of the eligible population needs to be fully vaccinated against the virus [13]. An important step towards COVID-19 vaccine acceptance is adequate knowledge of the disease and understanding attitudes towards mitigation measures [8]. Population-based surveys implemented in Kenya in early 2021 found high COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy that was associated with the low-risk perception of the disease, difficulty in adhering to government prevention measures, and concerns about vaccine safety and effectiveness [14,15]. Other studies in Africa have shown that despite good COVID-19 knowledge and attitudes, there were still a significant level of vaccine hesitancy [16,17]. Here, we assessed the level of COVID-19 knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) on acceptance and practice of COVID-19 mitigation measures among urban and rural populations—including estimating vaccine acceptability.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Setting and Design

We conducted a cross-sectional survey from 21 April to 5 May 2021 among residents enrolled in population-based infectious disease surveillance (PBIDS) in Kibera, Nairobi County and Asembo, Siaya County, Kenya [18]. The PBIDS platform was established by Kenya Medical Research Institute—Centre for Global Health Research (KEMRI-CGHR) with support from United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 2005 and has been described elsewhere [18]. Briefly, the PBIDS platform aims to assess the burden of acute infectious diseases and evaluate the impact of public health interventions within a 5 km and 1 km radius of a designated health facility in Asembo and Kibera, respectively. Kibera is a densely populated informal urban settlement with poor infrastructure and sanitation, unlike Asembo, which has a homogenous, sparsely populated rural area. Community interviewers regularly visit the households to collect demographic and health information using a standardized electronic questionnaire. All PBIDS participants have free access to medical care at the designated health facility at each site. Those presenting with acute respiratory, diarrheal, and/or febrile illness are consented for this systematic surveillance. By the end of June 2021, the Kibera site had 22,312 active participants in 5163 households, while the Asembo site had 32,149 participants in 16,365 households.

2.2. Sample Size Calculation

Our target was to enroll adults from ~225 households (approximately 450 adults based on average household size of 4) in each site. The KAP survey was a sub-set of an ongoing longitudinal SARS-CoV-2 sero-prevalence survey. The target sample size was based on an expected seroprevalence of 45% with a precision of 5%, 95% confidence interval, a design effect of 2, and 20% attrition. The possible seroprevalence of 45%, accounted for the recent seroprevalence of 13.3% detected in a general blood bank convenience sample in Kenya [19] and a 3.6× higher seroprevalence among slum residents than non-slum residents that was observed in India [20].

2.3. Study Population

We generated a sampling frame from the list of all household unique identifiers (IDs) for active PBIDS households. Using Excel, we then randomly selected a total of about 225 households to yield the desired sample size. All adults (≥18 years) residing in the randomly selected households from the two PBIDS sites, Asembo and Kibera, were eligible to participate. Household members found at home who consented to participate were enrolled, while the study team attempted to reach those not at home by revisiting their household three times.

2.4. Data Collection

Data were collected over a period of two weeks using a standardized KAP questionnaire programmed on netbooks or tablets. The questions were adopted from previous COVID-19 vaccine surveys carried out by the ministry of health, the population council of Kenya, and Trends and Insights For Africa (TIFA) research [14,21,22]. The questionnaires were administered by a research assistant and/or a trained fieldworker and the interviews lasted 30–45 min. The study questionnaire was sub-divided into 3 main sections: Biodata/socio-demographics, COVID-19 KAP and COVID-19 vaccine awareness and acceptability. The socio-demographic characteristics collected included age, sex, level of education, occupation, marital status, and religion. Data on COVID-19 Knowledge of transmission, clinical features and prevention was collected. To assess attitude towards COVID-19, participants were asked how dangerous they thought the disease was to their community and whether they thought they were at risk of contracting it. Additionally, we collected data on practice of COVID-19 mitigation measures such as handwashing, wearing of face masks, physical distancing and staying at home in the preceding 7 days. We also collected data on COVID-19 vaccine awareness, vaccine acceptability and any reasons for vaccine hesitancy. To assess vaccine awareness, we asked, “Is there a vaccine for COVID-19?”. To assess vaccine acceptability, participants were asked whether they would accept the COVID-19 vaccine if it was offered to them (Appendix A).

2.5. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using Stata (16.1, Stata Corp LLC, College Station, TX, USA). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize participants’ sociodemographic characteristics and KAP, as well as vaccine awareness and acceptability by frequencies, proportions and means. Survey data was weighted by ranking on sex and age group to the structure of the PBIDS population. The age groups applied were 18–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, and ≥60 years. Differences between urban and rural populations’ COVID-19 related practices were compared using Chi square test and Fisher’s exact test. Knowledge scores were calculated for each respondent as the proportion of correctly answered questions . Using modified Bloom’s cut-off points [23], the knowledge scores were then grouped into two categories: good knowledge scores (answered at least 6 out of the 8 knowledge questions correctly) and poor knowledge scores (answered less than 6 questions correctly). Multivariable logistic models were used to assess the factors associated with participants’ level of knowledge on COVID-19. The factors assessed were age groups, sex, occupation, education level, marital status, residence (rural-urban,) and religion. Occupation categories were reported as unemployed, employed formal, employed informal or self-employed. Education level was categorized as “None”, “Primary education (incomplete and complete primary)”, “Secondary education (incomplete and complete secondary)”, and “Post-secondary education”. Bivariate logistic regression was used to determine whether age, sex, occupation, and level of education were associated with being worried about contracting COVID-19. For vaccine acceptability, logistic regression was used to identify whether age, sex, occupation, education, COVID-19 knowledge, and risk perception were associated with acceptability. Factors that had a p-value ≤ 0.2 in the univariate analysis were considered for inclusion in the multivariable models. In the multivariable analysis, p-values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. For the logistic regression models, we accounted for clustering by household using clustered sandwich estimator [24,25].

2.6. Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval for this study was provided by the KEMRI Scientific and Ethical Review Committee in Kenya (KEMRI/SERU/4098) and protocol reliance provided by Washington State University. This project was also reviewed by CDC and conducted consistent with applicable federal law and CDC policy as provided for in the Code of Federal Regulations (45 C.F.R part 46 and 21 C.F.R. part 56). The PBIDS platform is approved by KEMRI Scientifical and Ethical Review Committee in Kenya (#2761), Washington State University reliance agreement and CDC reliance approval (#6775). Written consents were obtained from all study participants. Incentives were not provided to participants, although a bar of soap was given at the end of the study as a token of appreciation.

3. Results

3.1. Household and Participants’ Characteristics

Out of 440 eligible persons in Kibera, 398 (90.5%) were enrolled, 40 (9.1%) were unavailable during the study period, and 2 (0.4%) declined consent. In Asembo, 480 participants were eligible, with 458 (95.4%) agreeing to participate, 16 (3.3%) were unavailable, and 6 (1.3%) declining consent. The median age for the Asembo participants was 39.3 (IQR, 28.8–56.8) years and 33.0 (IQR, 25.0–43.0) years for the Kibera participants. Of those enrolled, 166 (36.2%) and 136 (34.2%) were males in Asembo and Kibera, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of study participants in Asembo, Siaya County and Kibera, Nairobi County, Kenya.

3.2. Knowledge on COVID-19

A total of 441 (96.3%) participants from Asembo and 380 (95.4%) from Kibera correctly answered ≥6 of the 8 knowledge questions (good knowledge score) with 308 (67.2%) respondents in Asembo and 254 (63.8%) in Kibera correctly answering all the knowledge questions. A high proportion of participants n Asembo (449, 97.8%) reported that COVID-19 is real compared to Kibera (370, 91.6%) (p-value = 0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Frequency of correct responses to the 8 knowledge questions in Asembo, Siaya County and Kibera, Nairobi County, Kenya.

On multivariable analysis, age, sex, occupation, and marital status were not significantly associated with good knowledge among the two populations (Table 3). However, those with secondary education in Kibera were more likely to have good knowledge scores compared to those with none (aOR, 4.02; 95% CI, 1.23–13.16).

Table 3.

Factors associated with good COVID-19 knowledge scores in Kibera, Nairobi and Asembo, Siaya County, Kenya on multivariable analysis.

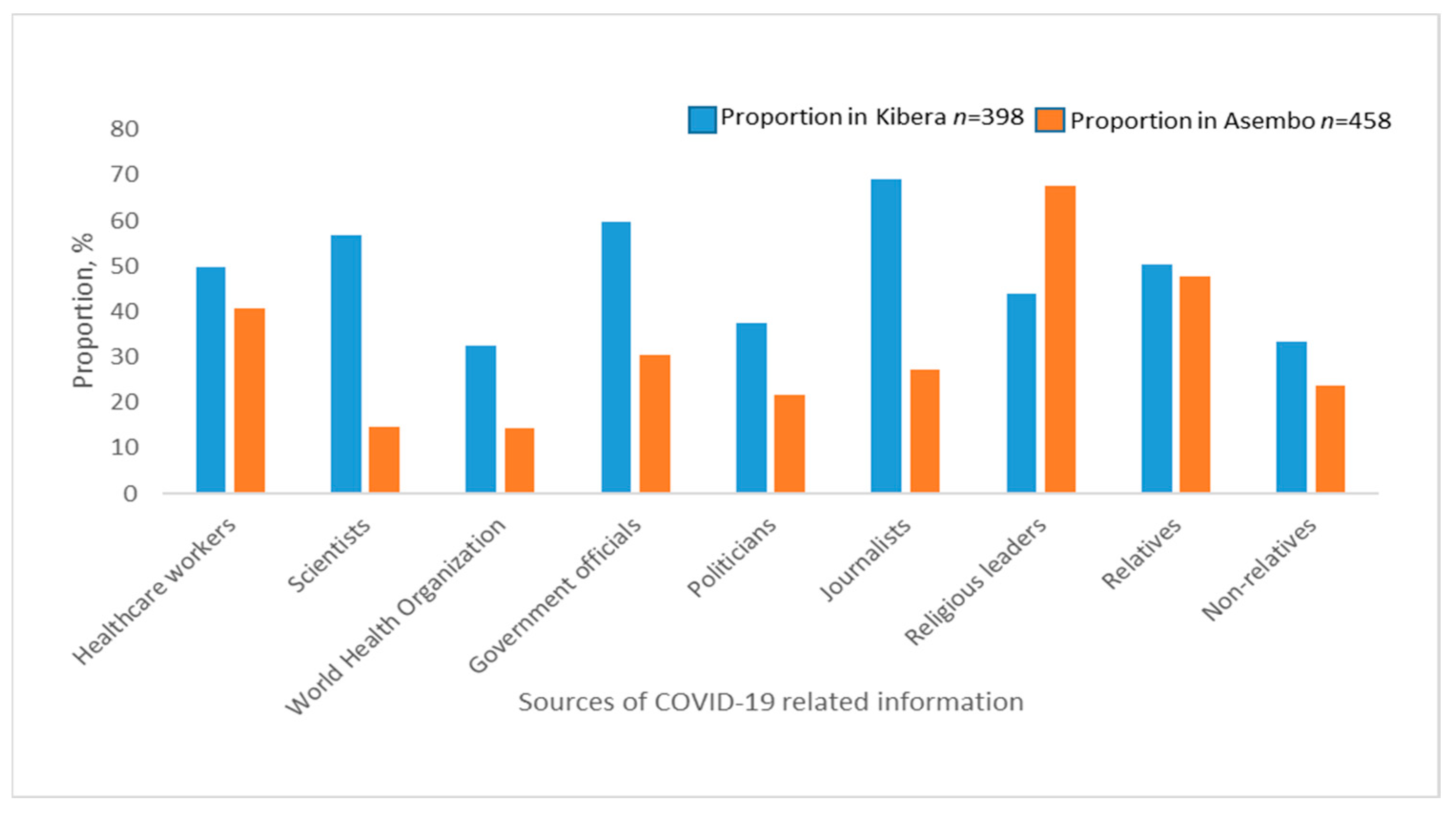

The most common sources of COVID-19 information were religious leaders (67.5%), relatives (47.8%) and healthcare workers (40.6%) in Asembo and journalists (69.1%), government authorities (59.8%), scientists (56.8%) in Kibera (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Sources of COVID-19 related information among study participants in Asembo and Kibera.

The most trusted source of COVID-19 information were religious leaders (97.1%), healthcare workers (95.2%), and government officials (90.7%) in Asembo, while in Kibera they were World Health Organization (WHO) (90.7%), scientists (86.7%), and healthcare workers (83.8%). Politicians were the least trusted sources of COVID-19 information in both Asembo (56.6%) and Kibera (46.3%) (Supplementary Figure S1).

3.3. Perceived Risk of Getting COVID-19

In Asembo, 413 (90.2%) participants and in Kibera, 327 (82.2%) were worried about contracting COVID-19. The perceived risk of getting COVID-19 was not associated with education level, sex, or marital status in both Kibera and Asembo (Table 4).

Table 4.

Factors associated with perceived risk of getting COVID-19 in Asembo, Siaya and Kibera, Nairobi County, Kenya on multivariable analysis.

Participants 60 years and older in Asembo were less likely to be worried about contracting COVID-19 (aOR 0.27; 95% CI, 0.07–0.98) as compared to those 18–29 years old. Those 40–49 years of age in Kibera were more likely to be worried about contracting COVID-19 (aOR 3.32; 95% CI, 1.37–8.03) compared to those of ages 18–29 years. Kibera participants 50–59 years of age were also more likely to be worried about contracting COVID-19 relative to the reference group (aOR 3.64; 95% CI, 1.15–11.49). In Kibera, those with formal employment (aOR, 0.18; 95% CI, 0.05–0.68) and the self-employed (aOR, 0.34; 95% CI, 0.15–0.77) were less likely to be worried about contracting COVID-19 as compared to the unemployed. There was no association between employment status and perceived risk of COVID-19 infection in Asembo. The majority of the respondents from both sites (82.0% from Asembo and 80.9% from Kibera) were generally satisfied with the government measures to prevent COVID-19 (Supplementary Table S1).

3.4. Practices

In the seven days preceding the interview, a vast majority of the participants in Asembo (438, 94.8%) and Kibera (381, 94.6%) reported practicing handwashing, with 72.2% and 67.8% of the participants always using soap when they washed their hands. Wearing face masks was reported by 426 (91.7%) of Asembo participants and 378 (94.4%) from Kibera. Five or more of the seven COVID-19 measures listed were practiced by 153 (35.2%) and 275 (68.0%) of Asembo and Kibera participants, respectively, within the previous seven days (Table 5).

Table 5.

Frequency of observing COVID-19 prevention practices among participants in Asembo, Siaya county and Kibera, Nairobi County **.

3.5. Vaccine Acceptability and Factors Associated

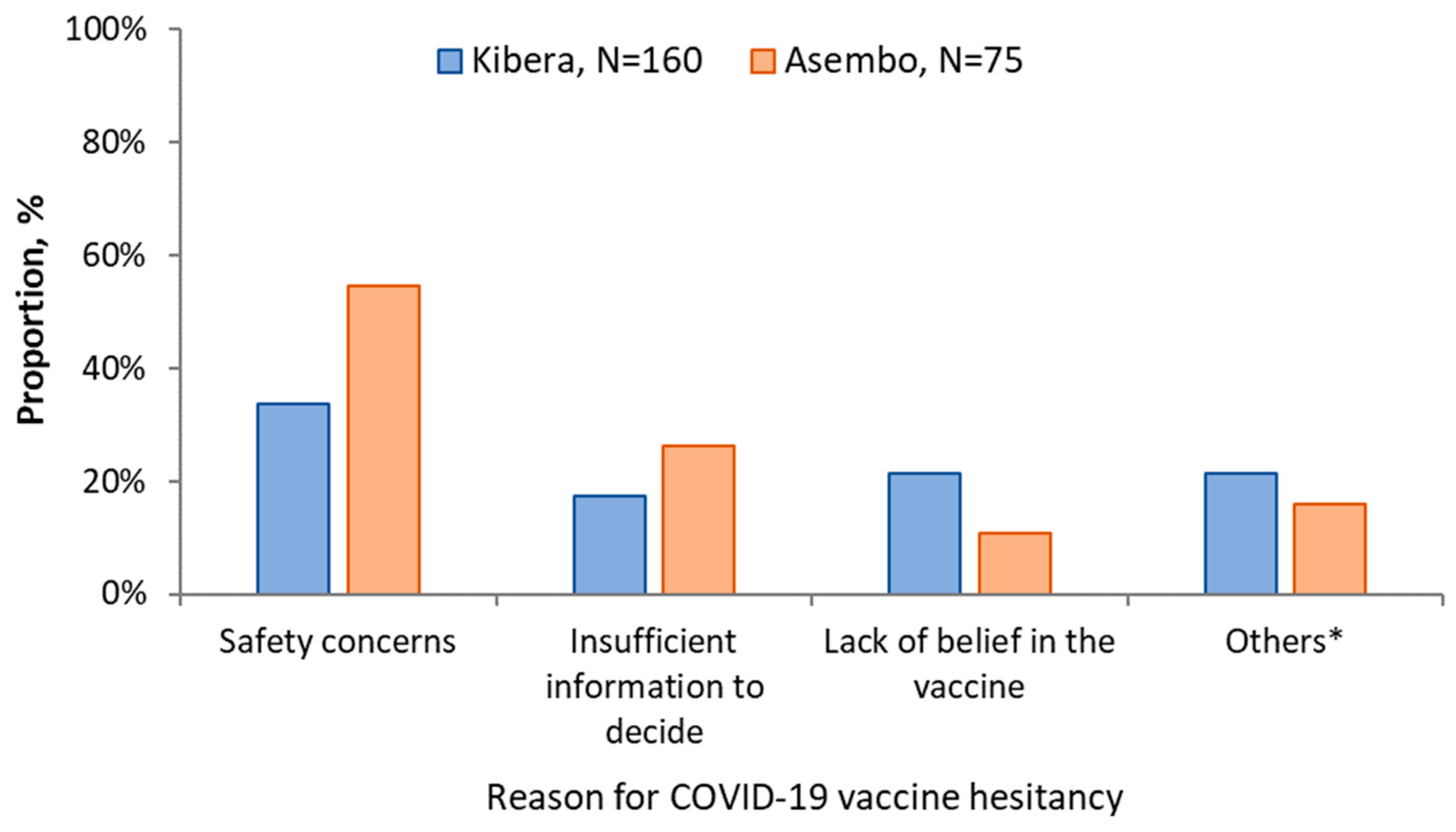

Awareness of the existence of a COVID-19 vaccine was higher in Asembo (411, 89.7%) than Kibera (266, 66.8%). If a COVID-19 vaccine was offered, 373 (83.6%; 95% CI, 79.9–86.9%) of the participants from Asembo and 231 (59.8%; 95% CI, 54.8–64.8) in Kibera would accept vaccination. Among the 75 who would not accept the vaccine in Asembo: 41 (54.7%) cited safety concerns; 20 (26.7%) insufficient information to decide; 8 (10.7%) didn’t believe in the vaccine and 2 (2.7%) felt they were not at risk of COVID-19. In Kibera: 54/160 (33.8%) were concerned about the safety of the vaccine; 34/160 (21.3%) didn’t believe in the vaccine; 28/160 (17.5%) insufficient information to decide; 9/160 (5.6%) were concerned about the effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccine and 9 (5.6%) felt they were not at risk of COVID-19 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Reasons for vaccine hesitancy among study participants in Asembo and Kibera, 2021. * Other reasons for Kibera include I am not at-risk (n = 9), vaccine not effective (n = 9), vaccine causes COVID-19 (n = 6), it is God’s will that I get sick (n = 2), and for Asembo include, I am not at-risk (n = 2), not eligible (n = 2), it is God’s will that I get sick (n = 2), cost (n = 1), and vaccine causes COVID-19 (n = 1).

In Kibera, those with post-secondary education were less likely to accept the vaccine compared to those without education (aOR, 0.40; CI, 0.18–0.85). Knowledge scores, age, sex, occupation, marital status and COVID-19 risk perception were not associated with vaccine acceptability (Table 6).

Table 6.

Factors associated with vaccine acceptability in Kibera, Nairobi and Asembo, Siaya County on multivariable analysis.

4. Discussion

We report a high level of COVID-19-related knowledge among adult residents in both Asembo (in rural Western Kenya) and Kibera (an informal urban settlement in Nairobi) as of May 2021. The primary sources of COVID-19 information were variable. People in Kibera and Asembo have some similar and some different trusted sources of information. Majority (>90%) of the respondents had a positive attitude towards mitigation measures at both rural and urban sites in Kenya. However, we observed lower awareness of COVID-19 vaccine existence (66.8%) and vaccine acceptance (59.8%) in Kibera compared to Asembo, an indicator of vaccine hesitancy, particularly in the informal urban population.

The high level of COVID-19 knowledge in the two populations may be due to extensive media coverage, including print and social media, of the pandemic since the first case was confirmed in March 2020 in Kenya. Utilization of formal and informal channels by the government to spread COVID-19 information may have successfully disseminated the information to both urban and rural populations [12]. Studies in other African countries and elsewhere have found moderate to high knowledge of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has been similarly attributed to media publicity and active public health programs [23,26]. Some of the common sources of vaccine information included social media and healthcare providers. In these studies, participants’ knowledge of COVID-19 was found to be associated with age, gender, education and past COVID-19 infection. Our study, however, found no association between knowledge scores and age, gender and occupation. Participants with secondary education from the informal settlement were up to four times more likely to have good knowledge compared to those with no education. This disparity could be a reflection of higher access to COVID-19 literature through programs implemented by the government and other partners [27,28]. Another study in Nigeria, conducted in March 2020, found less than a third of the participants had good COVID-19 knowledge, despite half the participants having more than a tertiary education [26]. This was a population-based study among both urban and peri-urban dwellers, unlike our study, which was in an informal urban settlement and a rural population. Despite knowledge being a prerequisite for positive practices and attitudes, a recent scoping review of COVID-19 knowledge, attitudes, and practices studies carried out in Sub-Saharan Africa found that most participants had adequate knowledge, although the attitudes and practices were not always positive [17].

Our study found that 40.2% of the informal urban population would not accept the vaccine if offered, compared to 16.4% of the rural participants. Studies carried out among informal urban settlements found vaccine hesitancy levels of 34% in Brazil [29] and 41.9% in Bangladesh [30]. In the Bangladesh study, the participants from an informal settlement were 3.8 times more likely to be hesitant to receive the COVID-19 vaccine relative to the other urban dwellers. The sub-optimal COVID-19 vaccine acceptability levels in the informal settlements may be attributable to differences in socio-demographic factors associated with vaccine acceptance, such as age, dependency on informal employment, and inadequate access to preventive measures [30,31]. Informal urban dwellers tend to be younger, hence more likely to have lower risk perceptions of COVID-19. Our findings were also higher and different from that of a study in South Africa, where the vaccine hesitancy was 21% among the urban participants and 31% among the rural study participants [32]. In our study, residents of the urban site were predominantly young and dependent on informal employment. With the widely circulated information that youth had a low-risk of developing severe COVID-19 disease, young people may consider themselves less vulnerable to the infection [33,34,35,36]. The young people may also assume that they will have mild disease in case of infection [36]. The informal settlement dwellers, who largely depend on informal employment for a living, have been more economically affected by the mitigation measures against the pandemic [37,38]. Informal settlements have historically had inadequate access to essential services such as water, healthcare, and sanitation [39]. This may lead to a feeling of being marginalized and a lack of confidence in COVID-19 prevention measures initiated by the government, including the vaccine [37,40]. The period preceding our survey had heightened media coverage on potential side effects, including the formation of blood clots related to the AstraZeneca vaccine [41,42,43]. This was the most available vaccine in Kenya at the time of the survey and may have reduced vaccine acceptability. In Africa, a study carried out to assess the determinants of vaccine acceptability before their roll-out found that uptake was potentially determined by the attitude of healthcare workers towards the vaccine, COVID-19 misinformation, religious beliefs, and social influencers [44]. They also found that addressing these factors would improve the acceptability of the vaccine [44]. The higher COVID-19 vaccine acceptance observed among the rural population in our study is likely attributed to the relatively older population who has a higher risk perception due to the association between old age and severe forms of COVID-19. It could also be the result of the inaccessibility of online media sources relaying negative COVID-19 vaccine information. Other studies have also found higher vaccine acceptance rates among the rural populations as compared to the urban ones [45,46]. These higher rates of vaccine acceptance in the rural populations were thought to be due to low knowledge about vaccine side effects, a greater proportion of older adults and people with comorbidities are at higher risks of severe COVID-19 [47]. However, other studies found that rural populations were more likely to be hesitant about receiving the COVID-19 vaccine [48,49]. A study carried out in Kenya just before the roll-out of the vaccine found that rural counties were 2.5 times more likely to report COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy compared to urban counties [14]. In this phone-based Kenyan study, the vaccine acceptance level was 53.8% in the rural counties and 75.9% in the urban counties. The vaccine hesitancy in these rural populations has been associated with the inconvenience of travel involved in accessing the vaccine and the lack of confidence in the vaccine.

Our study had some limitations. The participants were drawn from an informal settlement in the capital city of Kenya; therefore, the findings may not be generalizable to the rest of the urban population with different socio-economic characteristics. Additionally, respondents may provide favorable respondents since the data is self-reported. Despite these limitations, the strength of our study lies in the population-based random selection of households.

5. Conclusions

Our study highlights the need for the Ministry of Health and other public health stakeholders to address vaccine hesitancy to achieve the set vaccination targets. Educational programs promoting the benefits of the COVID-19 vaccine and more rapidly and effectively responding to reported safety and effectiveness concerns should be considered. Despite the good levels of COVID-19 knowledge, this study suggests that continued efforts be put into reinforcing the knowledge, attitude, and practices related to COVID-19 control. This study also indicates the need for additional studies to be carried out to provide more information on the drivers of vaccine hesitancy in Kenya.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/covid2100107/s1, Figure S1: Trusted Sources of COVID-19 information; Table S1: Attitudes of study participants towards COVID-19 in Kibera, Nairobi and Asembo, Siaya County, Kenya; Table S2: COVID-19 related practices among the study participants.

Author Contributions

C.N. developed the data collection tools, prepared an analysis plan, and drafted the manuscript. A.A., C.O. (Clifford Oduor) and C.O. (Cynthia Ombok) carried out daily data cleaning and carried out data analysis. D.O. trained the data collection teams and supervised the data collection. G.A. and A.O. developed data collection tools, trained the data collection teams, and supervised the data collection exercise. E.O., I.N. and R.N. developed the study protocol, developed the data collection tools and the data analysis plan. P.M. conceptualized the study and developed the study protocol. T.L. reviewed the study protocol, developed that study questionnaire, and reviewed the drafted manuscript. A.H.-R. conceptualized the study. G.B. and P.K.M. conceptualized the study, developed the study protocol, reviewed the data collection tools, reviewed the data analysis plan, carried out data analysis and drafted the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention through Cooperative Agreement #6U01GH002143, and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (Grant #INV-021779).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) Scientific and Ethical Review Unit (protocol number KEMRI/SERU/CGHR/366/4168) and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the KEMRI-CGHR field team for data collection, WSU-K for study implementation, and the CDC-Kenya Division of Global Health Protection for technical and financial support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A. Study Questionnaire

| Interviewer’s name: ____________________ Interviewer’s code: __ __ __ | |||||

| Interview date: __ __/__ __/__ __ | |||||

| Today’s date | ☐☐/☐☐/☐☐ | DSS Permanent ID | ☐☐/☐☐☐/☐☐/☐☐ | ||

| Site: | ☐ Asembo | ☐ Kibera | ☐ Manyatta | ☐ Other, specify__________ | |

Appendix A.1. Bio Data

| Participant name: | |

| Participant UNIQUE ID (DSS ID): | |

| Respondent | ≤Self ≤ Proxy |

| If proxy, specify the relationship with the participant | ≤Father ≤ Mother ≤ Uncle ≤ Aunt ≤ Other……… |

| Age | _______ ≤ years ≤ months (if <1 year) |

| Date of birth (MM/DD/YY) | |

| Sex | ≤Male ≤ Female |

| Phone number of self/HH head |

Appendix A.2. Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices

| Sources of COVID-19 Information | |

| In the past one week, from which of the following, if any, have you received news and information about COVID-19 (how)? Select all that apply. | 1 = Online sources (websites, social media) 2 = Messaging apps (WhatsApp)/SMS/text messaging 3 = Conversations (in person or phone) 4 = Newspapers 5 = Television 6 = Radio 7 = Others …. Specify |

| In the past week, from which of the following, if any, have you received news and information about COVID-19 (who)? Select all that apply. | 1 = Local health workers, clinics, and community organizations 2 = Scientists, doctors, and health experts 3 = World Health Organization (WHO) 4 = Government health authorities or other officials 5 = Politicians 6 = Journalists 7 = Religious leaders 8 = Relatives 9 = Non-relatives |

How much do you trust the following sources?

| 1 = Trust 2 = Somewhat trust 3 = Does not trust |

How much do you trust the following sources?

| 1 = Trust 2 = Somewhat trust 3 = Does not trust |

| COVID-19 Knowledge, Attitudes | |

| COVID-19 can spread when an infected person coughs or sneezes. | ☐ True ☐ False ☐ Don’t know/not sure ☐ Prefers not to answer |

| COVID-19 can spread from person-to-person when people are in close contact with each other. | ☐ True ☐ False ☐ Don’t know/not sure ☐ Prefers not to answer |

| A person can become infected with COVID-19 by touching a surface or object that has the virus on it and then touching their mouth, nose, or eyes. | ☐ True ☐ False ☐ Don’t know/not sure ☐ Prefers not to answer |

| A person infected with COVID-19 can transmit the virus to others even if they do not have symptoms. | ☐ True ☐ False ☐ Don’t know/not sure ☐ Prefers not to answer |

| Eating or touching wild animals could result in COVID-19 infection. | ☐ True ☐ False ☐ Don’t know/not sure ☐ Prefers not to answer |

| Only adults need to take precautionary measures to prevent the spread of COVID-19. | ☐ True ☐ False ☐ Don’t know/not sure ☐ Prefers not to answer |

| Young people can develop severe illnesses or die from COVID-19. | ☐ True ☐ False ☐ Don’t know/not sure ☐ Prefers not to answer |

| COVID-19 virus is real. | ☐ True ☐ False ☐ Don’t know/not sure ☐ Prefers not to answer |

| To prevent transmission of COVID-19 it is important to avoid going to crowded places. | ☐ True ☐ False ☐ Don’t know/not sure ☐ Prefers not to answer |

| Prevention measures | |

| What measures can you adopt to reduce the risk of contracting coronavirus/COVID-19? (Do not read out options—select all that apply) | 1 = Handwashing 2 = Use of hand sanitizers 3 = Keeping physical distance (>1.5M) 4 = Use of face mask 5 = Avoiding travel unless necessary 6 = Avoid crowded places 7 = Staying at home 8 = Get vaccinated 9 = Take medicines or herbs 10 = Other (specify)___________________ |

| In the past 7 days, what steps has your community/government taken to curb the spread of the coronavirus in your area (select all that apply)? | 1 = Advised citizens to stay at home 2 = Advised to avoid gatherings 3 = Restricted travel within county 4 = Restricted international travel 5 = Closure of non-essential businesses 6 = Created public awareness and sensitization of the community 7 = Closure of schools and universities 8 = Curfew and lockdown 9 = Established quarantine/isolation centres 10 = Disinfection of public places 11 = Vaccination 12 = Other (specify)__________________ |

| Overall, how satisfied are you with the measures your county/national government is taking to combat COVID-19? | 1 = Very satisfied 2 = Moderately satisfied 3 = Satisfied 4 = Moderately dissatisfied 5 = Very dissatisfied 6 = Neither satisfied or dissatisfied 7 = Don’t know 8 = Prefers not to say |

| Prevention measures practices | |

| Which of the following measures are you currently taking or have tried to take in the past 7 days (select all that apply)? | 1 = Handwashing 2 = Use of hand sanitizers 3 = Keeping physical distance (>1.5M) 4 = Use of face mask 5 = Avoiding travel unless necessary 6 = Avoiding crowded places 7 = Staying at home 8 = No measures taken 9 = Prefers not to say 10 = Other (specify)___________________ |

| In the past 7 days (Q26–Q29): | |

| When you clean your hands, how often are you able to clean your hands with soap or alcohol based hand sanitizer? | 1 = Never 2 = Sometimes 3 = Always |

| How often are you able to stay at least 1.5 m (arm’s length) away from people outside your household? | 1 = Never 2 = Sometimes 3 = Always |

| How often do you wear a mask or facecovering when you are in public? | 1 = Never 2 = Sometimes 3 = Always |

| How often do you stay at home? | 1 = Never (1) 2 = Rarely (2) 3 = Sometimes (3) 4 = Often (4) 5 = Always (5) |

| In the past 7 days, did you attend any social gatherings with family or friends? | ☐ Yes ☐ No ☐ Not sure ☐ Prefers not to answer |

| In the past 7 days, did you leave the house to go to work or to attend school? | ☐ Yes ☐ No ☐ Not sure ☐ Prefers not to answer |

If you tested positive for COVID-19 or think you might have COVID-19, how possible would it be for you to:

| 1 to 4 with 1 being very difficult and 4 being with ease |

| Perceived risk | |

| How dangerous do you think COVID-19 is a risk to your community? | 1 = Not at all dangerous 2 = Moderately dangerous 3 = Extremely dangerous 4 = Prefer not to answer |

| How worried are you about contracting COVID-19? | 1 = Not at all worried 2 = Somewhat worried Very worried 3 = Prefer not to answer |

| Vaccine awareness and acceptability | |

| ☐ Yes ☐ No ☐ Not sure ☐ Prefers not to answer |

| 1 = Yes, definitely 2 = No, definitely not 3 = Not sure/Don’t know 4 = Not answered |

If “no, definitely not” or “not sure/don’t know”,

| 1 = Concerned over side effects and/or safety 2 = Concerned that it won’t be effective at preventing COVID-19 3 = I do not need it/I am not at risk 4 = Underlying health condition/ineligible to receive it 5 = The cost 6 = Concerned the vaccine can cause COVID-19 7 = I don’t believe in the vaccine/COVID-19 8 = God’s will if I get sick 9 = I don’t have enough information to decide 10 = Other (specify)____________________ 11 = Prefer not to answer |

| Impact of COVID-19 | |

| How worried are you about not having enough food in your household? | 1 = Not at all worried Somewhat worried 2 = Greatly worried 3 = Prefer not to answer |

| If worried (a little, somewhat, or greatly), Since COVID-19 has been in Kenya (March 2020), has your worry about not having enough food in your household… | 1 = Increased a lot 2 = Increased a little 3 = Decreased a lot 4 = Decreased a little 5 = Stayed the same (no difference) |

| How has your work changed since COVID-19 has been in Kenya (March 2020)? | 1 = No longer employed (1) 2 = Newly employed (2) 3 = Employed in a different business (3) 4 = Role substantially changed with same business (4) 5 = Little or no change (5) |

| Since COVID-19 has been in Kenya (March 2020), have you lost earnings because of the virus or because of the restrictions? | ☐ Yes ☐ No ☐ Not sure ☐ Prefers not to answer |

| If yes, What are the main areas of expenditure if any that you have had to reduce, delay, or eliminate altogether? (multiple responses up to three) | 1 = Food 2 = Clothing/goods 3 = Transportation 4 = Rent 5 = Entertainment 6 = Assistance to others 7 = Repayment of loans 8 = Cooking fuel School fees 9 = Electricity/water 10 = Alcohol 11 = Medicines/treatment 12 = Air-time 13 = No changes 14 = Don’t know 15 = Prefers not to answer 16 = Other .. specify |

| Anxiety | |

| In the last 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by the following problems? Feeling nervous or anxious Not being able to stop or control worrying Worrying/thinking too much about different things Trouble relaxing Being so restless that it is hard to sit still Becoming easily annoyed or irritable Feeling afraid as if something awful might happen | 1 = Not at all 2 = Several days 3 = More than half the days 4 = Nearly every day |

References

- WHO. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available online: https://covid19.who.int (accessed on 10 August 2021).

- Nasimiyu, C.; Matoke-Muhia, D.; Rono, G.K.; Osoro, E.; Ouso, D.O.; Mwangi, J.M.; Mwikwabe, N.; Thiong’o, K.; Dawa, J.; Ngere, I.; et al. Imported SARS-CoV-2 Variants of Concern Drove Spread of Infections across Kenya during the Second Year of the Pandemic. COVID 2022, 2, 586–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gueye, K.; Padane, A.; Diédhiou, C.K.; Ndiour, S.; Diagne, N.D.; Mboup, A.; Mbow, M.; Lo, C.I.; Leye, N.; Ndoye, A.S.; et al. Evolution of SARS-CoV-2 Strains in Senegal: From a Wild Wuhan Strain to the Omicron Variant. COVID 2022, 2, 1116–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Zhao, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Fan, G.; Xu, J.; Gu, X.; et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020, 395, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaife, M.; van Zandvoort, K.; Gimma, A.; Shah, K.; McCreesh, N.; Prem, K.; Barasa, E.; Mwanga, D.; Kangwana, B.; Pinchoff, J.; et al. The impact of COVID-19 control measures on social contacts and transmission in Kenyan informal settlements. BMC Med. 2020, 18, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COVID-19 for Africa: Lockdown Exit Strategies|United Nations Economic Commission for Africa. Available online: https://www.uneca.org/covid-19-africa-lockdown-exit-strategies (accessed on 27 July 2021).

- Kitara, D.L.; Ikoona, E.N. COVID-19 pandemic, Uganda’s story. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2020, 35, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azlan, A.A.; Hamzah, M.R.; Sern, T.J.; Ayub, S.H.; Mohamad, E. Public knowledge, attitudes and practices towards COVID-19: A cross-sectional study in Malaysia. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0233668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COVID-19 Vaccines: Everything You Need to Know. Available online: https://www.gavi.org/covid19-vaccines (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- McNamara, D. Delta Variant Could Drive “Herd Immunity” Threshold over 80%. Available online: https://www.webmd.com/lung/news/20210803/delta-variant-could-drive-herd-immunity-threshold-over-80 (accessed on 23 September 2021).

- Kenya Receives COVID-19 Vaccines and Launches Landmark National Campaign. Available online: https://www.afro.who.int/news/kenya-receives-covid-19-vaccines-and-launches-landmark-national-campaign (accessed on 12 May 2022).

- Ministry of Health—Republic of Kenya. Available online: https://www.health.go.ke/ (accessed on 9 June 2021).

- Murewanhema, G.; Dzinamarira, T.; Chingombe, I.; Mapingure, M.P.; Mukwenha, S.; Chitungo, I.; Herrera, H.; Madziva, R.; Ngwenya, S.; Musuka, G. Emerging SARS-CoV-2 Variants, Inequitable Vaccine Distribution, and Implications for COVID-19 Control in Sub-Saharan Africa. COVID 2022, 2, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orangi, S.; Pinchoff, J.; Mwanga, D.; Abuya, T.; Hamaluba, M.; Warimwe, G.; Austrian, K.; Barasa, E. Assessing the level and determinants of COVID-19 Vaccine Confidence in Kenya. Vaccines 2021, 9, 936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocholla, B.A.; Nyangena, O.; Murayi, H.K.; Mwangi, J.W.; Belle, S.K.; Ondeko, P.; Kendagor, R. Association of Demographic and Occupational Factors with SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine Uptake in Kenya. Open Access Libr. J. 2021, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuben, R.C.; Danladi, M.M.A.; Saleh, D.A.; Ejembi, P.E. Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices Towards COVID-19: An Epidemiological Survey in North-Central Nigeria. J. Community Health 2020, 46, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwagbara, U.I.; Osual, E.C.; Chireshe, R.; Bolarinwa, O.A.; Saeed, B.Q.; Khuzwayo, N.; Hlongwana, K.W. Knowledge, attitude, perception, and preventative practices towards COVID-19 in sub-Saharan Africa: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0249853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feikin, D.R.; Olack, B.; Bigogo, G.M.; Audi, A.; Cosmas, L.; Aura, B.; Burke, H.; Njenga, M.K.; Williamson, J.; Breiman, R.F. The Burden of Common Infectious Disease Syndromes at the Clinic and Household Level from Population-Based Surveillance in Rural and Urban Kenya. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e16085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyoga, S.; Adetifa, I.M.O.; Karanja, H.K.; Nyagwange, J.; Tuju, J.; Wanjiku, P.; Aman, R.; Mwangangi, M.; Amoth, P.; Kasera, K.; et al. Seroprevalence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies in Kenyan blood donors. Science 2021, 371, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malani, A.; Shah, D.; Kang, G.; Lobo, G.N.; Shastri, J.; Mohanan, M.; Jain, R.; Agrawal, S.; Juneja, S.; Imad, S.; et al. Seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in slums versus non-slums in Mumbai, India. Lancet Glob. Health 2021, 9, e110–e111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2020 Year End Survey: Festive Season Plans and COVID-19 Issues. TIFA Research 2020. Available online: http://www.tifaresearch.com/2020-year-end-survey-festive-season-plans-and-covid19-issues/ (accessed on 28 June 2022).

- Ministry-of-Health-Kenya-Covid-19-Immunization-Status-Report-17th-January-2022. Available online: https://www.health.go.ke/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/MINISTRY-OF-HEALTH-KENYA-COVID-19-IMMUNIZATION-STATUS-REPORT-17TH-JANUARY-2022.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2022).

- Feleke, B.T.; Wale, M.Z.; Yirsaw, M.T. Knowledge, attitude and preventive practice towards COVID-19 and associated factors among outpatient service visitors at Debre Markos compressive specialized hospital, north-west Ethiopia, 2020. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0251708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, H. A Heteroskedasticity-Consistent Covariance Matrix Estimator and a Direct Test for Heteroskedasticity. Econometrica 1980, 48, 817–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, P.J. The Behavior of Maximum Likelihood Estimates under Nonstandard Conditions. 1967. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/52597492/The_behavior_of_maximum_likelihood_estimates_under_nonstandard_conditions (accessed on 8 June 2022).

- Habib, M.A.; Dayyab, F.M.; Iliyasu, G.; Habib, A.G. Knowledge, attitude and practice survey of COVID-19 pandemic in Northern Nigeria. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0245176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenya_basic_Education_COVID-19_Emergency_Response_Plan-compressed. Available online: https://www.education.go.ke/images/Kenya_basic_Education_COVID-19_Emergency_Response_Plan-compressed (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Lewis. Keeping Children in Nairobi Informal Settlement Safe from COVID-19. Kenya Community Media Network 2021. Available online: https://kcomnet.org/keeping-children-in-nairobi-informal-settlement-safe-from-covid-19/ (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Aguilar Ticona, J.P.; Nery, N.; Victoriano, R.; Fofana, M.O.; Ribeiro, G.S.; Giorgi, E.; Reis, M.G.; Ko, A.I.; Costa, F. Willingness to Get the COVID-19 Vaccine among Residents of Slum Settlements. Vaccines 2021, 9, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedin, M.; Islam, M.A.; Rahman, F.N.; Reza, H.M.; Hossain, M.Z.; Hossain, M.A.; Arefin, A.; Hossain, A. Willingness to vaccinate against COVID-19 among Bangladeshi adults: Understanding the strategies to optimize vaccination coverage. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0250495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mohaithef, M.; Padhi, B.K. Determinants of COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance in Saudi Arabia: A Web-Based National Survey. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2020, 13, 1657–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, S.; van Rooyen, H.; Wiysonge, C.S. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in South Africa: How can we maximize uptake of COVID-19 vaccines? Expert Rev. Vaccines 2021, 20, 921–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhopal, S.S.; Bagaria, J.; Olabi, B.; Bhopal, R. Children and young people remain at low risk of COVID-19 mortality. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2021, 5, e12–e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Society, C.P. Canadian Study Confirms Children and Youth at Low Risk of Severe COVID-19 during First Part of Pandemic|Canadian Paediatric Society. Available online: https://cps.ca/en/media/canadian-study-confirms-children-and-youth-at-low-risk-of-severe-covid-19-during-first-part-of-pandemic (accessed on 28 June 2022).

- Snape, M.D.; Viner, R.M. COVID-19 in children and young people. Science 2020, 370, 286–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karijo, E.; Wamugi, S.; Lemanyishoe, S.; Njuki, J.; Boit, F.; Kibui, V.; Karanja, S.; Abuya, T. Knowledge, attitudes, practices, and the effects of COVID-19 among the youth in Kenya. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyadera, I.N.; Onditi, F. COVID-19 experience among slum dwellers in Nairobi: A double tragedy or useful lesson for public health reforms? Int. Soc. Work. 2020, 63, 838–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuwematsiko, R.; Nabiryo, M.; Bomboka, J.B.; Nalinya, S.; Musoke, D.; Okello, D.; Wanyenze, R.K. Unintended socio-economic and health consequences of COVID-19 among slum dwellers in Kampala, Uganda. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Health of People Who Live in Slums. Available online: https://www.thelancet.com/series/slum-health (accessed on 27 September 2021).

- Auerbach, A.M.; Thachil, T. How Does COVID-19 Affect Urban Slums? Evidence from Settlement Leaders in India. World Dev. 2021, 140, 105304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinho, A.C. AstraZeneca’s COVID-19 Vaccine: EMA Finds Possible Link to Very Rare Cases of Unusual Blood Clots with Low Platelets. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/astrazenecas-covid-19-vaccine-ema-finds-possible-link-very-rare-cases-unusual-blood-clots-low-blood (accessed on 20 June 2021).

- Adverse Effects from Covid Jab Reported in Kenya—Kagwe. Available online: https://www.the-star.co.ke/news/2021-04-06-277-adverse-effects-from-covid-jab-reported-in-kenya-kagwe/ (accessed on 22 July 2021).

- Ray, S.U.K. Reports 30 Cases of Rare Blood Clots Linked to AstraZeneca Vaccine, Insists Benefits Outweigh Any Risks. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/siladityaray/2021/04/02/uk-reports-30-cases-of-rare-blood-clots-linked-to-astrazeneca-vaccine-insists-benefits-outweigh-any-risks/ (accessed on 22 July 2021).

- Wirsiy, F.S.; Nkfusai, C.N.; Ako-Arrey, D.E.; Dongmo, E.K.; Manjong, F.T.; Cumber, S.N. Acceptability of COVID-19 Vaccine in Africa. Int. J. Matern. Child Health AIDS 2021, 10, 134–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiful Haque, M.M.; Rahman, M.L.; Hossian, M.; Matin, K.F.; Nabi, M.H.; Saha, S.; Hasan, M.; Manna, R.M.; Barsha, S.Y.; Hasan, S.M.R.; et al. Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine and its determinants: Evidence from a large sample study in Bangladesh. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, A.; Sikdar, D.; Mahanta, J.; Ghosh, S.; Jabed, M.A.; Paul, S.; Yeasmin, F.; Sikdar, S.; Chowdhury, B.; Nath, T.K. Peoples’ understanding, acceptance, and perceived challenges of vaccination against COVID-19: A cross-sectional study in Bangladesh. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0256493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, B.P. Disparities in COVID-19 Vaccination Coverage Between Urban and Rural Counties—United States, December 14, 2020–April 10, 2021. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021, 70, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luyten, J.; Bruyneel, L.; van Hoek, A.J. Assessing vaccine hesitancy in the UK population using a generalized vaccine hesitancy survey instrument. Vaccine 2019, 37, 2494–2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudson, A.; Montelpare, W.J. Predictors of Vaccine Hesitancy: Implications for COVID-19 Public Health Messaging. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).