Impact of Crisis on Sustainable Business Model Innovation—The Role of Technology Innovation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Literature Review on Crisis

2.1.1. The Concept of a Crisis

2.1.2. Crisis Theory

2.1.3. Characteristics and Trends of Crisis Research

2.2. Literature Review on Sustainable Business Model Innovation

2.2.1. Defining the Business Model

2.2.2. Business Model Innovation

2.2.3. Classifying Business Model Innovation and Sustainable Goal

2.3. Research on the Relationship between Crisis and Technological and Sustainable Business Model Innovations

2.3.1. The Relationship between Crisis and Technology Innovation

2.3.2. The Relationship between Crisis and Technological and Sustainable Business Model Innovations

3. Study Design

3.1. Study Methodology

3.2. Case Selection

3.3. Text Collection

3.3.1. Text Collection Method

3.3.2. Text Analysis Method

4. Study Results and Encoding Analysis

4.1. Open Encoding

4.2. Spindle Encoding

4.3. Selective Encoding

4.4. Theoretical Saturation Test

5. Model Interpretation and Case Discovery

- Production factor crisis–introduced technology innovation–efficient business model innovation,

- Market environment crisis–differentiated and socialized technology innovation–novel business model innovation,

- Business ethics crisis–socialized and differentiated technology innovation–co-benefit business model innovation.

5.1. Production Factor Crisis—Introduced Technology Innovation Improves Efficiency

5.1.1. Mechanism Process

5.1.2. Practical Case: Alibaba Introduces a Big Data Algorithm to Identify False Suppliers

5.2. Market Environment Crisis—Socialization and Differentiation of Technology Innovation Will Determine the New Direction

5.2.1. Mechanism Process

5.2.2. Practical Case: Vipshop Opens Up the Technical Cooperation Path to Recover Customers

5.3. Business Ethics Crisis—Socialization and Differentiation of Technology Innovation Will Reconstruct Common Benefits

5.3.1. Mechanism Process

5.3.2. Practical Case: Baidu Is Committed to a Number of Beneficial Plans to Review Its Bidding Ranking Feature

5.4. Case Findings

6. Conclusions and Outlook

6.1. Study Conclusions

6.2. Countermeasures and Suggestions

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gilbert, C. Crisis Analysis: Between Normalization and Avoidance. J. Risk Res. 2007, 10, 925–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, W.T.; Holladay, S.J. Communication and Attributions in a Crisis: An Experimental Study in Crisis Communication. J. Public Relations Res. 1996, 8, 279–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaksic, M.L. Sustainable innovation of technology and business models: Rethinking business strategy. South-East. Eur. J. Econ. 2016, 2, 127–139. [Google Scholar]

- Vidmar, D. Technology Enabled Sustainable Business Model Innovation. In Proceedings of the 31st Bled eConference: Digital Transformation–From Connecting Things to Transforming Our Lives, Bled, Slovenia, 18–21 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, H.; Chu, S. Public Crisis Management under the New Media Environment-a Case Study on Weibo. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Mechatronic Systems and Materials Application (ICMSMA 2017), Singapore, 7–8 May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cleeren, K.; Dekimpe, M.G.; Heerde, H.J.V. Marketing Research on Product-Harm Crises: A Review, Managerial Implications, and an Agenda for Future Research. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2017, 45, 593–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gausemeier, J.; Kage, M. From rapid prototyping to home fabrication: How 3D printing is changing business model innovation. Z. Für Wirtsch. Fabr. 2017, 112, 459–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Heerde, H.; Helsen, K.; Dekimpe, M.G. The Impact of a Product-Harm Crisis on Marketing Effectiveness. Mark. Sci. 2007, 26, 230–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saradhi, V.V.; Palshikar, G.K. Employee churn prediction. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011, 38, 1999–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Zhang, L.; Li, F.; Wang, G. The Effects of Product-Harm Crisis on Brand Performance. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2010, 52, 443–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clauss, T.; Breier, M.; Kraus, S.; Durst, S.; Mahto, R.V. Temporary business model innovation–SMEs’ innovation response to the COVID-19 crisis. R D Manag. 2021, 52, 294–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snihur, Y.; Zott, C.; Amit, R. Managing the Value Appropriation Dilemma in Business Model Innovation. Strat. Sci. 2021, 6, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, W. Administration and the Crisis in Legitimacy: A Review of Habermasian Thought. Harv. Educ. Rev. 1980, 50, 496–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, U.; Pijnenburg, B. Crisis Management and Decision Making: Simulation Oriented Scenarios; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, L. Crisis in Organizations: Managing and Communicating in the Heat of Chaos; South-Western Publishing Company: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Green, P.S. Reputation risk management. In Financial Times; Pitman Publishing: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Lerbinger, O. The crisis manager: Facing risk and responsibility (book review). J. Mass Commun. Q. 1997, 74, 646. [Google Scholar]

- Amankwah-Amoah, J.; Wang, X. Opening Editorial: Contemporary Business Risks: An Overview and New Research Agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 97, 208–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahadevan, B. Business Models for Internet-Based E-Commerce: An Anatomy. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2000, 42, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimitt, M.; Grégoire, B.; Incoul, C.; Dubois, E.; Brimont, P. If business models could speak! Efficient:a framework for appraisal, design and simulation of electronic business transactions. In Knowledge Sharing in the Integrated Enterprise; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Magretta, J. Why business models matter. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2002, 80, 86–92. [Google Scholar]

- Zott, C.; Amit, R.; Donlevy, J. Strategies for value creation in e-commerce: Best. Eur. Manag. J. 2000, 18, 463–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubosson-Torbay, M.; Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y. E-business model design, classification, and measurements. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2002, 44, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlegelmilch, B.B.; Diamantopoulos, A.; Kreuz, P. Strategic innovation: The construct, its drivers and its strategic outcomes. J. Strat. Mark. 2003, 11, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y. Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changes and Challenges; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Chesbrough, H.; Ahern, S.; Finn, M.; Guerraz, S. Business Models for Technology in the Developing World: The Role of Non-Governmental Organizations. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2006, 48, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.L. Big Data and the Innovation Cycle. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2018, 27, 1642–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dmitriev, V.; Simmons, G.; Truong, Y.; Palmer, M.; Schneckenberg, D. An exploration of business model development in the commercialization of technology innovations. R D Manag. 2014, 44, 306–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, S.; Xu, X. Business model innovation: An integrated approach based on elements and functions. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2016, 17, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorbach, S.; Wipfler, H.; Schimpf, S. Business Model Innovation vs. Business Model Inertia: The Role of Disruptive Technologies. Berg. Huettenmaenn Monatsh. 2017, 162, 382–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Andreini, D.; Bettinelli, C.; Foss, N.J.; Mismetti, M. Business model innovation: A review of the process-based literature. J. Manag. Gov. 2021, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.W.; Christensen, C.M.; Kagermann, H. Reinventing your business model. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2008, 86, 57–68. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, M. Business model innovation: Past research, current debates, and future directions. J. Strat. Manag. 2017, 10, 342–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zott, C.; Amit, R.; Center, S.E. Measuring the Performance Implications of Business Model Design: Evidence From Emerging Growth Public Firms; INSEAD: Singapore, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Zott, C.; Amit, R. The fit between product market strategy and business model: Implications for firm performance. Strat. Manag. J. 2008, 29, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurland, N.B. Accountability and the public benefit corporation. Bus. Horiz. 2017, 60, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumpeter, J.A. Business Cycles: A Theoretical, Historical and Statistical Analysis of the Capital Process; Mc Graw-Hill, VOLS.: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 1939. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, N. Empirical Evaluation of Long Waves of Capitalist Development. Critique 2020, 48, 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, R.; Conboy, K. The role of IS in the COVID-19 pandemic: A liquid-modern perspective. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 55, 102184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, G.; Griffiths, M. Digital transformation during a lockdown. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 55, 102185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vial, G. Understanding digital transformation: A review and a research agenda. Manag. Digit. Transform. 2021, 28, 13–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaswamy, V. Co-creation of value—towards an expanded paradigm of value creation. Mark. Rev. St. Gallen 2009, 26, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiel, D.; Arnold, C.; Voigt, K.-I. The influence of the Industrial Internet of Things on business models of established manufacturing companies–A business level perspective. Technovation 2017, 68, 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Ponce, P.; Tanveer, M.; Aguirre-Padilla, N.; Mahmood, H.; Shah, S. Technological Innovation and Circular Economy Practices: Business Strategies to Mitigate the Effects of COVID-19. Sustainability 2021, 13, 58479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smajlović, S.; Umihanić, B.; Turulja, L. The interplay of technological innovation and business model innovation toward company performance. Manag. J. Contemp. Manag. Issues 2019, 24, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baden-Fuller, C.; Haefliger, S. Business Models and Technological Innovation. Long Range Plann. 2013, 46, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaulio, M.; Thorén, K.; Rohrbeck, R. Double ambidexterity: How a Telco incumbent used business-model and technology innovations to successfully respond to three major disruptions. Creativity Innov. Manag. 2017, 26, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roehrich, R.L. The Relationship between Technological and Business Innovation. J. Bus. Strat. 1984, 5, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Yang, D.; Sun, B.; Gu, M. The fit between technological innovation and business model design for firm growth: Evidence from China. Soc. Sci. Electron. Publ. 2014, 44, 288–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schallmo, D.; Williams, C.A. Crisis-Driven Business Model Innovation–Decision-Making under Stress. In Proceedings of the ISPIM Connects Global 2020: Celebrating the World of Innovation, Virtual, 6–8 December 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Baker-Brunnbauer, J. Business Model Innovation during the Corona Crisis. Preprint 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morkunas, V.J.; Paschen, J.; Boon, E. How blockchain technologies impact your business model. Bus. Horiz. 2019, 62, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Song, M.L.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, G. Innovation network, technological learning and innovation performance of high-tech cluster enterprises. J. Knowl. Manag. 2019, 23, 1729–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willems, K.; Verhulst, N.; Brengman, M. How COVID-19 Could Accelerate the Adoption of New Retail Technologies and Enhance the (E-) servicescape. In The Future of Service Post-COVID-19 Pandemic; Springer: Singapore, 2021; Volume 2, pp. 103–134. [Google Scholar]

- Koen, P.A.; Bertels, H.M.J.; Elsum, I.R. The three faces of business model innovation: Challenges for established firms. Res. Technol. Manag. 2011, 54, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jernigan, D.H. Meeting the Challenge of Change. Health Promot. Pract. 2009, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, L.L.; Rindova, V.P.; Greenbaum, B.E. Unlocking the Hidden Value of Concepts: A Cognitive Approach to Business Model Innovation. Strat. Entrep. J. 2015, 9, 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clauss, T. Measuring business model innovation: Conceptualization, scale development, and proof of performance. R&D Manag. 2017, 47, 385–403. [Google Scholar]

- Nußholz, J.; Rasmussen, F.N.; Milios, L. Circular building materials: Carbon saving potential and the role of business model innovation and public policy. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 141, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Wang, H.; Chiang, D. Study on Positive and Dynamic Enterprise Crisis Management based on Sustainable Business Model Innovation. Adv. Inf. Sci. Serv. Sci. 2013, 5, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumpeter, J.A. Theory of Economic Development: An Inquiry into Profits, Capital, Credit, Interest, and the Business Cycle; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Drucker, P.F. Innovation and Entrepreneurship: Practice and Principles; Harper and Row.43. Potocan, V. Technology and Corporate Social Responsibility: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Ye, Y. Research on Selection of Technological Innovation Mode for Large and Medium-Sized Construction Enterprises in China. Technol. Investig. 2017, 8, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calia, R.C.; Guerrini, F.M.; Moura, G.L. Innovation networks: From technological development to business model reconfig-uration. Technovation 2007, 27, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zott, C.; Amit, R. Business Model Design and the Performance of Entrepreneurial Firms. Organ. Sci. 2007, 18, 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serfati, C. Financial dimensions of transnational corporations, global value chain and technological innovation. J. Innov. Econ. Manag. 2008, 2, 35–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jetter, M.; Satzger, G.; Neus, A. Technological innovation and its impact on business model, organization and corporate culture–ibm’s transformation into a globally integrated, service-oriented enterprise. Wirtschaftsinformatik 2009, 51, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Mu, R.; Hu, S.; Wang, L.; Wang, S. Intellectual property protection, technological innovation and enterprise value-an empirical study on panel data of 80 advanced manufacturing smes. Cogn. Syst. Res. 2018, 52, 741–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalilabadi, S.M.G.; Zegordi, S.H.; Nikbakhsh, E. A multi-stage stochastic programming approach for supply chain risk mitigation via product substitution. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 149, 106786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aviso, K.; Mayol, A.; Promentilla, M.; Santos, J.; Tan, R.; Ubando, A.; Yu, K. Allocating human resources in organizations operating under crisis conditions: A fuzzy input-output optimization modeling framework. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 128, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnegan, D.; Willcocks, L. Knowledge sharing issues in the introduction of a new technology. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2006, 19, 568–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, P.; Panday, S. Innovative Strategies for Supply Chain Sustainability-in Competitive Global Business Envi-ronments. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Integral Development for Wholesome Life-In the Pious Presence of H.H. Acharya Shri Mahashramanji with Special Focus on Morality & Ethical Value System for Wholesome Development Organised, Forest Grove, OR, USA, 4–5 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Higa, K. Organizational Innovation by Efficient Resource Allocation: A Proposal of Telework-based Organization. In Proceedings of the Japan Telework Society Conference, Tokyo, Japan, 26 November 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Shirai, K.; Koshijima, I.; Umeda, T. Technology and human resource alignment for business innovation program. J. Int. Assoc. Proj. Program Manag. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.K.; Zhuang, G.; Li, S. Will Consumers Pay More for Efficient Delivery? An Empirical Study of What Affects E-Customers’ Satisfaction and Willingness to Pay on Online Shopping in Bangladesh. Sustainability 2020, 12, 31121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.K.; Martin, M.J.C. Disruptive technologies, stakeholders and the innovation value-added chain: A framework for evaluating radical technology development. Soc. Sci. Electron. Publ. 2005, 35, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trachuk, A.; Linder, N. Knowledge Spillover Effects: Impact of Export Learning Effects on Companies’ Innovative Activities. In Current Issues in Knowledge Management; IntechOpen: Vienna, Austria, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Lu, J. Discussion of Smes’ Technology Innovation Strategy in China under the Background of Post-Financial Crisis. Econ. Manag. J. 2012, 2, 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Z.Y.; Diao, Z.F. Study on the Enterprise Business Model Innovation Based on the Industrial Value Chain. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Productinnovation Management, Xian, China, 26–27 December 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Adda, G.; Azigwe, J.B.; Awuni, A.R. Business Ethics and Corporate Social Responsibility for Business Success and Growth. Eur. J. Bus. Innov. Res. 2016, 4, 26–42. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Zhu, Y. Enterprise technological innovation and intellectual property rights system construction. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, N.J.; Raja, V. Protecting the privacy and security of sensitive customer data in the cloud. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 2012, 28, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potocan, V. Technology and Corporate Social Responsibility. Sustainability 2021, 13, 58658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.M.; Trimi, S. Convergence innovation in the digital age and in the COVID-19 pandemic crisis. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 123, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Sun, R.; Zhao, H.; Zheng, L.; Shen, C. Linking work-related and non-work-related supervisor-subordinate relationships to knowledge hiding: A psychological safety lens. Asian Bus. Manag. 2022, 21, 525–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Company Full Name | Creation Time | Company Location | Major Businesses |

|---|---|---|---|

| E-commerce Industry | |||

| JD | 1998 | Beijing, China | Online shop, logistics, finance, etc. |

| Alibaba | 1999 | Zhejiang, China | E-commerce, logistics network, new retail, cloud computing, etc. |

| Vipshop | 2008 | Guangzhou, China | Online sales of brand discount goods on the internet, covering major categories such as clothing, shoes and bags, beauty and other products |

| ZTO | 2013 | Shanghai, China | Domestic express, international express, etc. |

| Pingduoduo | 2015 | Shanghai, China | Third-party social e-commerce platform focusing on Customer To Manufacturer (C2M) group shopping |

| Taobao | 2003 | Zhejiang, China | The online retail trading platform launched by Alibaba |

| Alipay | 2004 | Zhejiang, China | Third-party payment platform, mainly for mobile payment, electronic payment |

| Manufacturing Industry (Information and Communication Technology) | |||

| TCL Technology (TCL) | 1982 | Guangdong, China | Semiconductors, electronic products and communication equipment, new optoelectronics, liquid crystal display devices |

| Huawei Technoligies (Huawei) | 1987 | Guangdong, China | IT, radio, microelectronics, communications, routing, program-controlled switches, etc. |

| China Telecom | 1995 | Beijing, China | Fixed communication business, mobile communication business |

| IFlytek | 1999 | Anhui, China | Value-added telecommunications services; computer software and hardware development, production and sales; electronic products, computer communication equipment research and development, etc. |

| China Mobile Communications Group (China Mobile) | 2000 | Beijing, China | Fixed communication business, mobile communication business |

| Xiaomi | 2010 | Beijing, China | Digital products, software, etc. |

| Manufacturing Industry (Electrical Manufacturing) | |||

| Changhong Electric (Changhong) | 1958 | Sichuan, China | Household appliances, automotive appliances, electronic products and spare parts, etc. |

| Midea | 1968 | Guangdong, China | Household appliances, etc. |

| Galanz | 1978 | Guangdong, China | Home appliances, microwave ovens |

| Haier | 1984 | Shandong, China | Development and sales of refrigerators, air conditioners, electric freezers, washing machines and other home appliances |

| AUX | 1986 | Zhejiang, China | Home appliance, electric equipment, medical, real estate, financial investment |

| Gree Electric Appliances (Gree) | 1991 | Guangdong, China | Home appliances, mainly air conditioners |

| Chigo | 1994 | Guangdong, China | Home appliances, mainly air conditioners |

| Manufacturing Industry (Automotive Manufacturing) | |||

| BYD | 1995 | Guangdong, China | Automotive, rail transportation, new energy and electronics |

| Tesla | 2003 | Palo Alto, USA | Electric vehicle sales and leasing business, energy and energy storage business, etc. |

| Contemporary Amperex Technology Co., Limited (CATL) | 2011 | Fujian, China | Lithium-ion batteries, lithium polymer batteries, fuel cells, power batteries, etc. |

| Nio | 2014 | Shanghai, China | High-performance smart electric vehicles with the ultimate user experience |

| Xiaopeng | 2014 | Guangdong, China | Main production of cars |

| Manufacturing Industry (Petrochemicals) | |||

| China National Offshore Oil Corporation(Cnooc) | 1982 | Beijing, China | Oil exploration, production and sales |

| Sinopec | 1983 | Beijing, China | Oil trading, oil extraction, storage, transportation and chemical industry, etc. |

| Asea Brown Boveri (ABB) | 1988 | Zurich, Switzerland | Power technology, automation technology and oil/gas/petrochemical industry and robotics |

| Social Media Industry | |||

| Tencent | 1998 | Guangdong, China | Media platforms, online advertising, financial technology and corporate services |

| Sina | 1998 | Beijing, China | Mobile Value Added Services (MVAS), internet video, music streaming, online games, photo albums, blogs, email, etc. |

| Baidu | 2000 | Beijing, China | Search platform, cloud services, etc. |

| Aliyun | 2009 | Zhejiang, China | Technology facilities to support digitization and intelligence launched by Alibaba |

| Sina Microblog | 2009 | Beijing, China | Sina’s social media platform and software for sharing daily life |

| 1999 | Guangdong, China | A live chat tool launched by Tencent | |

| 2011 | Guangdong, China | An instant messaging software launched by Tencent | |

| Base Category | Secondary Category | Concept | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Production factor crisis | Supply interruption crisis | Rapid changes in the external environment of the supply chain |

|

| Risk transmission to the supply chain enterprise |

| ||

| Labor shortage crisis | Structural shortage of available labor |

| |

| Labor quality and adaptability shortage |

| ||

| Market environment crisis | Excessive competition crisis | Homogeneous competition |

|

| Cross-border squeeze competition |

| ||

| Customer loss crisis | Exogenous customer loss |

| |

| Endogenous customer loss |

| ||

| Business ethics crisis | Ethical crisis | Enterprises violate the laws and regulations |

|

| The internal interests of the enterprise are inconsistent |

|

| Base Category | Secondary Category | Concept | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

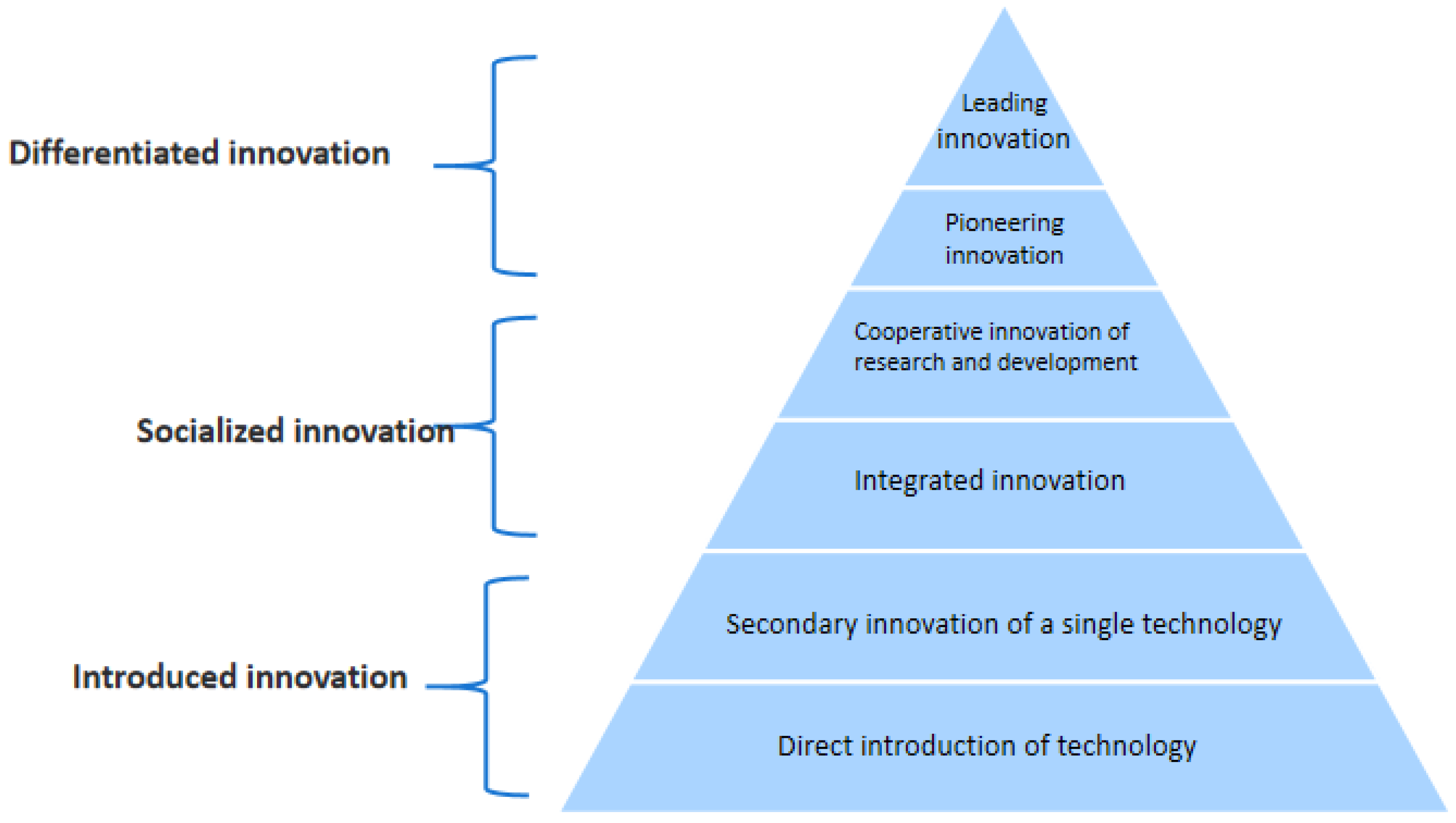

| Introduced innovation | Direct introduction of technology | Introduction of product technology |

|

| Introduction of process technology |

| ||

| Secondary innovation of a single technology | Imitation innovation |

| |

| Transformation innovation |

| ||

| Socialized innovation | Integrated innovation | Enterprise resource integration |

|

| Supply chain integration |

| ||

| Cooperative innovation of research and development | Leading role in cooperative innovation |

| |

| Equal role in cooperative innovation |

| ||

| Differentiated innovation | Pioneering innovation | Original innovation of technology principle |

|

| Original innovation of technological achievement |

| ||

| Leading innovation | Maintaining new technology advantage |

| |

| Implementing advanced technology and achieving a leading advantage |

|

| Base Category | Secondary Category | Concept | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Efficient business model innovation | Resource allocation innovation | Capital saving |

|

| Labor release |

| ||

| Integration innovation of the value chain | Key optimization of business innovation |

| |

| Effective supply chain innovation |

| ||

| Novel business model innovation | Value structure innovation | Innovation in trading methods |

|

| Business content innovation |

| ||

| Value connection innovation | External value input |

| |

| External value extension |

| ||

| Common benefit type business model innovation | Cross-industry co-benefit | Integration of business forms |

|

| Benefit government and enterprise |

| ||

| Co-benefit environment | Low carbon strategy |

|

| Typical Relationship Structure | The Connotation of the Relationship Structure |

|---|---|

| When encountering a production factor crisis such as a supply interruption or labor shortage, enterprises start with the introduced technology and, with the help of external technology innovation, implement the necessary value updates and logic improvements to effectively allocate the resources, integrate the value chain, and improve the efficiency of the business model. |

| When the competition in the market environment intensifies and enterprises lose customers, they must search for valuable and scarce elements through differentiated or socialized innovations to enhance their competitive advantages based on heterogeneous resource endowments, realize the business path through the capture value of information and data flow, and improve the novelty of the business model. |

| The new era of business ethics is more challenging. Therefore, enterprise differentiates innovative technology (e.g., big data, cloud computing, and artificial intelligence), which is at the core of the enterprise, and auxiliary social technology innovation is used to reshape its operating scenarios and patterns. Simultaneously, it adds value to the beneficial optimization relationship with stakeholders and extends the life cycle of value creation in the process of co-benefit business model innovation. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zheng, L.; Dong, Y.; Chen, J.; Li, Y.; Li, W.; Su, M. Impact of Crisis on Sustainable Business Model Innovation—The Role of Technology Innovation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11596. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811596

Zheng L, Dong Y, Chen J, Li Y, Li W, Su M. Impact of Crisis on Sustainable Business Model Innovation—The Role of Technology Innovation. Sustainability. 2022; 14(18):11596. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811596

Chicago/Turabian StyleZheng, Linlin, Yashi Dong, Jineng Chen, Yuyi Li, Wenzhuo Li, and Miaolian Su. 2022. "Impact of Crisis on Sustainable Business Model Innovation—The Role of Technology Innovation" Sustainability 14, no. 18: 11596. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811596