Introducing a Puppy to Existing Household Cat(s): Mixed Method Analysis

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

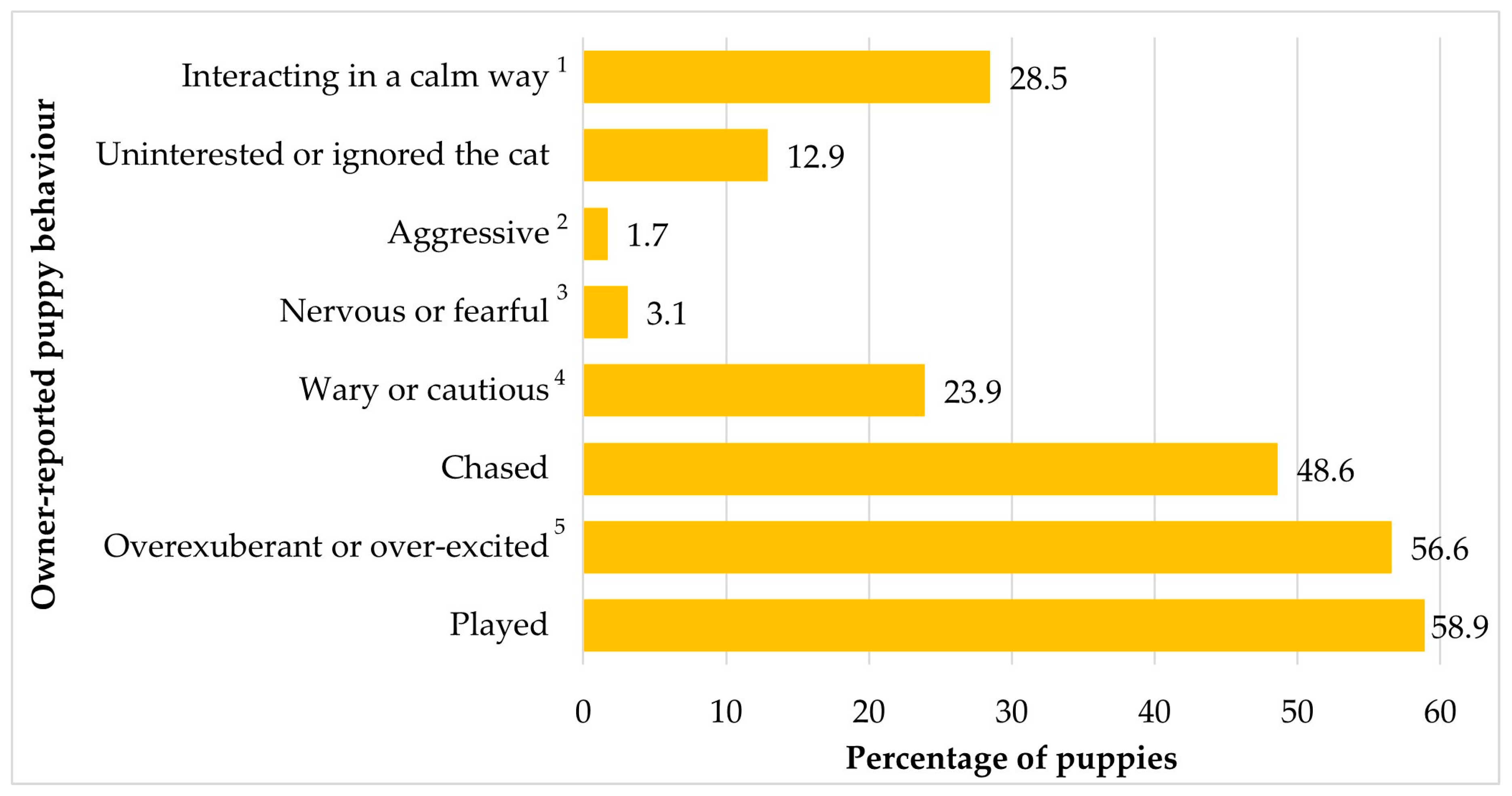

- owner-reported puppy behaviour following introduction to existing household cat(s);

- quantitative analysis of factors associated with owner reported ‘only desirable’ puppy behaviour towards household cats following introduction; and

- qualitative analysis of owners’ approaches to introducing a puppy to a household cat and perceptions of the emerging cat-dog relationship.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Data Collection and Study Size

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Qualitative Analysis

2.6. Ethical Approval and Consent to Participate

3. Results

3.1. Results of Statistical Analysis

3.2. Qualitative Findings

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Murray, J.; Gruffydd-Jones, T.; Roberts, M.; Browne, W. Assessing changes in the UK pet cat and dog populations: Numbers and household ownership. Vet. Rec. 2015, 177, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, M. Integrative Development of Brain and Behavior in the Dog; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Beaver, B. Feline Behavior: A Guide for Veterinarians; W.B. Saunders Company: St. Louis, MO, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Serpell, J.; Jagoe, J. Chapter 6: Early experience and the development of behaviour. In The Domestic Dog—Its Evolution, Behaviour and Interactions with People; Serpell, J., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995; pp. 131–138. [Google Scholar]

- Feuerstein, N.; Terkel, J. Interrelationships of dogs (Canis familiaris) and cats (Felis catus L.) living under the same roof. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2008, 113, 150–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foreman-Worsley, R.; Farnworth, M. A systematic review of social and environmental factors and their implications for indoor cat welfare. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2019, 220, 104841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buller, K.; Ballantyne, K. Living with and loving a pet with behavioral problems: Pet owners’ experiences. J. Vet. Behav. 2020, 37, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, M.; New, J.; Scarlett, J.; Kass, P.; Ruch-Gallie, R.; Hetts, S. Human and animal factors related to relinquishment of dogs and cats in 12 selected animal shelters in the United States. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 1998, 1, 207–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scarlett, J.; Salman, M.; New, J.; Kass, P. Reasons for relinquishment of companion animals in U.S. animal shelters: Selected health and personal issues. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 1999, 2, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, J.; Hall, S.; Mills, D. Evaluation of the relationship between cats and dogs living in the same home. J. Vet. Behav. 2018, 27, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, M. Behavioral Effects of Rearing Dogs With Cats During the ‘Critical Period of Socialization’. Behaviour 1969, 35, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogs Trust. Dogs and Cats Living Together. Available online: https://www.dogstrust.org.uk/help-advice/dog-care/dogs-and-cats-living-together (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- International Cat Care. Introducing and Managing Cats and Dogs. Available online: https://icatcare.org/advice/introducing-a-cat-or-kitten-to-your-dog/ (accessed on 5 July 2022).

- PDSA. How to Introduce a Dog and Cat. Available online: https://www.pdsa.org.uk/pet-help-and-advice/looking-after-your-pet/all-pets/introducing-cats-and-dogs (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Vets4Pets. Introducing Puppies to Cats. Available online: https://www.vets4pets.com/pet-health-advice/dog-advice/puppy/introducing-puppies-to-cats/#:~:text=The%20first%20meeting%20should%20take,your%20puppy%20and%20your%20cat (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Haywood, C.; Ripari, L.; Puzzo, J.; Foreman-Worsley, R.; Finka, L. Providing humans with practical, best practice handling guidelines during human-cat interactions increases cats’ affiliative behaviour and reduces aggression and signs of conflict. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, J.; Kinsman, R.; Lord, M.; Da Costa, R.; Woodward, J.; Owczarczak-Garstecka, S.C.; Casey, R.A. ‘Generation Pup’—protocol for a longitudinal study of dog behaviour and health. BMC Vet. Res. 2021, 17, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetters, M.; Curry, L.; Creswell, J. Achieving integration in mixed methods designs-principles and practices. Health Serv. Res. 2013, 48 Pt 2, 2134–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.; Fuller, J. Genetics and the Social Behaviour of the Dog; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Dohoo, I.; Martin, W.; Stryhn, H. Veterinary Epidemiologic Research; University of Prince Edward Island: Charlottetown, PE, Canada, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pallant, J. SPSS Survival Manual, 5th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education (UK): Maidenhead, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, V.; Braun, V.; Hayfield, N. Thematic Analysis. In Qualitative Psychology: A Practical Guide to Research Methods; Smith, J., Ed.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2015; pp. 222–248. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V.; Rance, N. How to use thematic analysis with interview data. In The Counselling and Psychotherapy Research Handbook; Vossler, A., Moller, N., Eds.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2014; pp. 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PDSA. How Many Pets Are There in the UK? Available online: https://www.pdsa.org.uk/what-we-do/pdsa-animal-wellbeing-report/uk-pet-populations-of-dogs-cats-and-rabbits (accessed on 3 May 2022).

- PFMA. Historical Pet Population. Available online: https://www.pfma.org.uk/historical-pet-population (accessed on 3 May 2022).

- Nohr, E.; Liew, Z. How to investigate and adjust for selection bias in cohort studies. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2018, 97, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, M. Understanding Your Dog; McCann and Geoghegan: New York, NY, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Bekoff, M. Social play and play-soliciting by infant canids. Am. Zool. 1974, 14, 323–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, E.; Smuts, B. Cooperation and competition during dyadic play in domestic dogs, Canis familiaris. Anim. Behav. 2007, 73, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panksepp, J. Affective Neuroscience: The Foundations of Human and Animal Emotions; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Coppinger, R.; Feinstein, M. How Dogs Work; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, M.; Hecht, J. A review of the development and functions of cat play, with future research considerations. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2019, 214, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, D.; Diniz de Moura, R.; Serpell, J. Development and evaluation of the Fe-BARQ: A new survey instrument for measuring behavior in domestic cats (Felis s. catus). Behav. Processes 2017, 141, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westgarth, C.; Pinchbeck, G.; Bradshaw, J.; Dawson, S.; Gaskell, R.M.; Christley, R.M. Factors associated with cat ownership in a community in the UK. Vet Rec. 2010, 166, 354–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouton, M.; Winterbaouer, N.; Todd, T. Relapse processes after the extinction of instrumental learning: Renewal, resurgance and reacquisition. Behav. Processes 2012, 90, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porritt, F.; Shapiro, M.; Waggoner, P.; Mitchell, E.; Thomson, T.; Nicklin, S.; Kacelnik, A. Performance decline by search dogs in repetitive tasks, and mitigation strategies. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2015, 166, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpless, S.; Jasper, H. Habituation of the arousal reaction. Brain 1956, 79, 655–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rochlitz, I. Feline welfare issues. In The Domestic Cat: The Biology of Its Behaviour, 3rd ed.; Turner, D., Bateson, P., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014; pp. 131–153. [Google Scholar]

- Menchetti, L.; Calipari, S.; Mariti, C.; Gazzano, A.; Diverio, S. Cats and dogs: Best friends or deadly enemies? What the owners of cats and dogs living in the same household think about their relationship with people and other pets. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menchetti, L.; Calipari, S.; Guelfi, G.; Catanzaro, A.; Diverio, S. My Dog Is Not My Cat: Owner Perception of the Personalities of Dogs and Cats Living in the Same Household. Animals 2018, 8, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Piirainen, E. Idiom motivation from cultural perspectives: Metaphors, symbols, intertextuality. In Linguocultural Competence and Phraseological Motivation; Pamies, A., Dobrovol’skij, D., Eds.; Schneider Hohengehren: Baltmannsweiler, Germany, 2011; pp. 65–74. [Google Scholar]

| Categorisation | Behaviour | Definition Examples |

|---|---|---|

| ‘Desirable’ behaviour | Interacting in a calm way | Sniffing or sleeping with the cat(s) |

| Uninterested or ignored the cat(s) | - | |

| ‘Undesirable’ behaviour | Aggressive | Growling or snapping |

| Nervous or fearful | Moving into another room or freezing | |

| Wary or cautious | Keeping a distance or cowering during the interactions | |

| Chased the cat(s) | - | |

| Overexuberant or over-excited | Persistently trying to interact | |

| Played with the cat(s) | - |

| Introduction Speed | |

|---|---|

| Immediately (they were together straight away) | |

| Quite quickly (interaction was controlled for up to the first 2 h after they met) | |

| Quite gradually (their meeting was gradual over the first day) | |

| Gradually (they were introduced slowly over a period of more than one day) | 487 (40.2) |

| Introduction Speed | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Immediately (they were together straight away) | 243 (20.1) |

| Quite quickly (interaction was controlled for up to the first 2 h after they met) | 229 (18.9) |

| Quite gradually (their meeting was gradual over the first day) | 252 (20.8) |

| Gradually (they were introduced slowly over a period of more than one day) | 487 (40.2) |

| Variable | Category | ‘Only Desirable’ Behaviours n (%) | ‘One or More Undesirable’ Behaviours n (%) | OR (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex of puppy | Male | 50 (8.1) | 569 (91.9) | 1.00 | |

| Female | 38 (6.4) | 554 (93.6) | 0.78 (0.50–1.21) | 0.267 | |

| Number of cats in household | Continuous variable | 1.05 (0.92–1.19) | 0.482 | ||

| Number of dogs in household | Continuous variable | 1.28 (1.14–1.43) | <0.001 | ||

| Another dog aged ≥ 1 year in household | No | 33 (4.6) | 690 (95.4) | 1.00 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 55 (11.3%) | 433 (88.7) | 2.66 (1.70–4.16) | ||

| Introduction speed 1 | Immediately/quite quickly | 24 (5.1) | 448 (94.9) | 1.00 | |

| Gradually/quite gradually | 64 (8.7) | 675 (91.3) | 1.77 (1.09–2.87) | 0.021 | |

| Age puppy joined household | Continuous variable | 1.00 (0.99–1.02) | 0.596 | ||

| Age of puppy when cat-dog data were collected | 12 to 22 weeks | 55 (5.5) | 951 (94.5) | 1.00 | <0.001 |

| <12 weeks | 33 (16.9) | 162 (83.1) | 0.28 (0.18–0.45) | ||

| Kennel Club group 2 | Non purebred dog and all other Kennel Club groups | 69 (6.6) | 982 (93.4) | 1.00 | 0.018 |

| Pastoral | 19 (11.9) | 141 (88.1) | 1.92 (1.12–3.28) | ||

| Variable | Category | ‘Only Desirable’ Behaviours n (%) | ‘One or More Undesirable’ Behaviours n (%) | OR (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of dogs in household | Continuous variable | 1.31 (1.16–1.46) | <0.001 | ||

| Introduction speed 1 | Immediately/quite quickly | 24 (5.1) | 448 (94.9) | 1.00 | 0.013 |

| Gradually/quite gradually | 64 (8.7) | 675 (91.3) | 1.86 (1.14–3.05) | ||

| Age of puppy when cat-dog data were collected | 12 to 22 weeks | 35 (4.9) | 681 (95.1) | 1.00 | <0.001 |

| <12 weeks | 53 (10.7) | 442 (89.3) | 2.52 (1.60–3.96) | ||

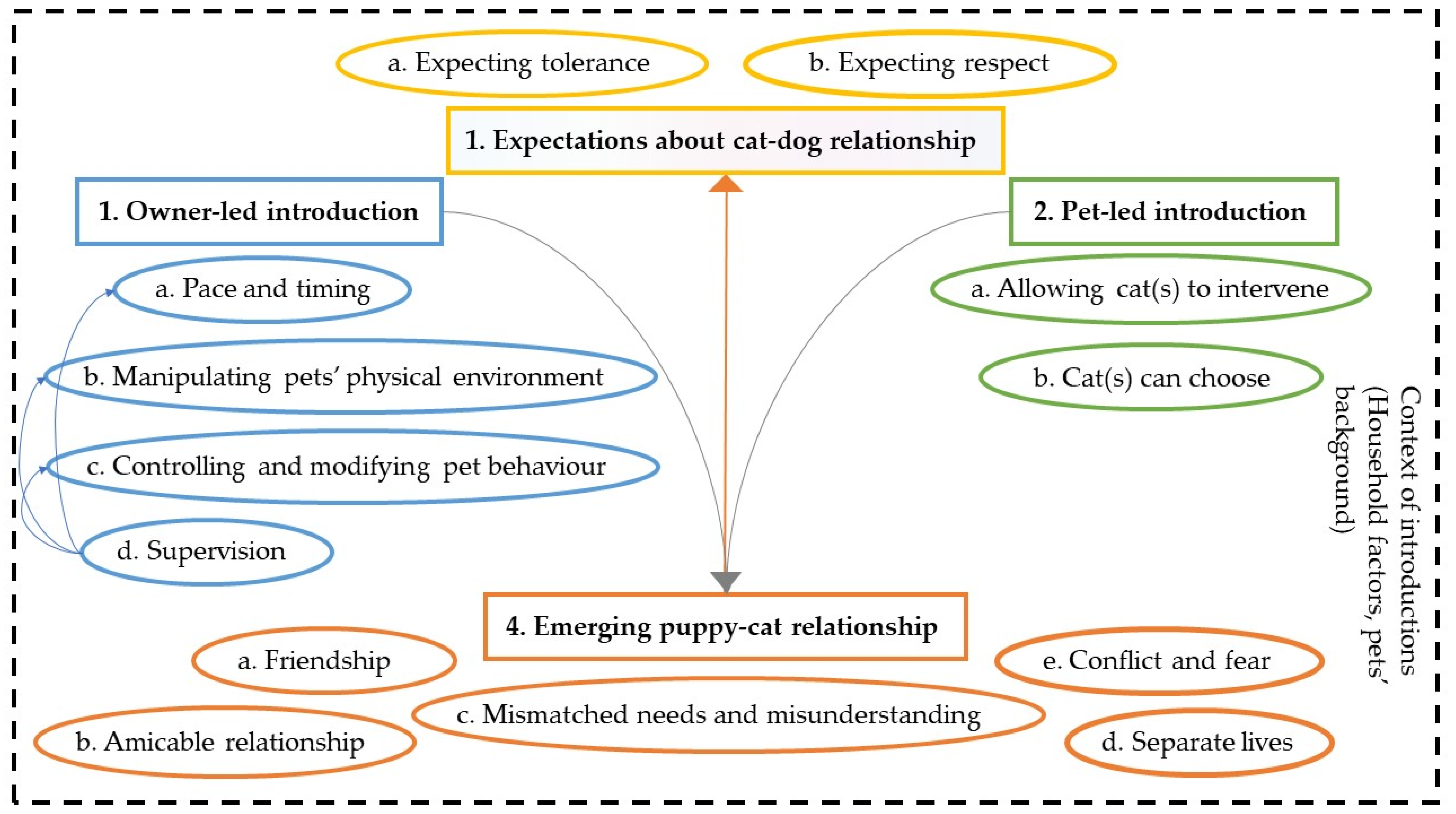

| Theme | Sub-Theme | Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Owner-led introduction | Pace and timing | “We let them play for short intervals and stop before they get over excited/hurt” “I gradually introduce the puppies to our cats from around 4 weeks of age (when I feel comfortable that the cats will not harm them)” |

| Manipulating pets’ physical environment | “Prior to getting [the puppy], we set our house up with stairgates and see-through room dividers” “We have her food/water bowls upstairs in a safe space, so she doesn’t have to be around the puppy in order to eat or drink” “They [the cats] have plenty of spaces high up to get away from her [the dog] (…)” | |

| Controlling and modifying pet behaviour | “We have not allowed [the puppy] to get too excited around them [the cats], and we calmly divert her attention if her arousal levels become too high” “When [the puppy] has spotted her [the cat] we have rewarded calm behaviour” “[The puppy] is not allowed to be loose with the cats, she is always on a training line” “We scold her [the puppy] verbally each time she does it [chases cats] and sometimes remove her from the area to give them [the cats] an opportunity to go wherever they want to without fleeing for their lives” “Today she [the cat] came most of the way down whilst he [the puppy] was at the foot of the stairs and I drip fed them both high value food (chicken) to reinforce the positive, calm interaction” | |

| Supervision | “At the moment we are monitoring their interaction and don’t leave them alone in the same room” “Introductions between [the puppy] and the cats have been closely supervised, on-lead or through the stairgates or room dividers” | |

| 2. Pet-led introduction | Allowing cat(s) to intervene | “They [the cats] introduced themselves. They are well able to look after themselves if they choose to get on the floor” “Cats put him in his place, and they play now, and the cats are the boss” “One cat is slowly sorting the puppy out” “If [the puppy] ever pushes it too far and the cat doesn’t want to play anymore the cat will give her a bop on the nose (without her being hurt)” |

| Cat(s) can choose | “Their introduction will go as quickly as the cat wants” “The cats have their own access to the house away from [the puppy] so they can adapt to a boisterous puppy in the house” “We have kept [the puppy] apart from the cats where possible, allowing the cats to choose when to come near” | |

| 3. Emerging cat-dog relationship | Friendship | “There’s a little bit of grooming each other. And they often fall asleep next to each other” “Often it is the cat that starts the play fighting. At other times they play very gently or play jointly with a toy, sometimes they sleep together” |

| Amicable relationship | “She [the puppy] has been relatively calm with the cats so they have increasingly tolerated being near her” “After 1 week cat chose to sit in lounge where dog was” “She [the cat] has come and sniffed [the puppy], and walked away” “They are co-existing well” | |

| Mismatched needs and misunderstandings | “[The puppy] is really curious about the cats, he will stand still and watch them then slowly approach, but they run away” “[The puppy] is very inquisitive and wants to play with everyone and everything, he is learning slowly that cats don’t play” “He [the puppy] then chases them because they run, so he thinks it’s a game and he wants to play” | |

| Separate lives | “The girl cat (…) does not like the dogs so she stays away or keeps her distance” “Mostly they are calm and tend to ignore each other” | |

| Conflict and fear | “[The cat] is not impressed as all. In fact, I think he’s a little frightened of her” “They will all sit together for treat but [the puppy] is cautious as she [the cat] is a cat that ALWAYS growls” “[The cat] hits [the puppy] a lot but rarely with claws out (…) [the cat] often runs away from [the puppy]” | |

| 4. Expectations about cat-dog relationship | Expecting tolerance | “They [the cats] are not anxious or aggressive towards him [the puppy], they just tolerate him and stay out of his way” “One cat treats [the puppy] with gentle disdain and they are mutually tolerant to the point where [the puppy] allows the cat to share his food” |

| Expecting respect | “[The cat] has been wary of [the puppy] but she will correct his behaviour which I think is good for him, so he learns to be respectful as early as possible” “[The cat] is a lot tougher and has shown her [the puppy] who’s boss and [the puppy] respects that it seems and doesn’t chase said cat, but is still dead keen to be mates” “The cat took one look at me “what have you done!” [The puppy] is respectful of cat now” | |

| 5. Context of introductions | Layout of the house | “We had to introduce them quickly as it would have been too difficult to keep separate due to house layout” |

| Cat’s history | “The cat is a rescue (…) and has socialisation issues from her previous experiences and is unlikely to tolerate a formal introduction” “[The cat] has been living with my previous dog since we rescued when she was 4 years old. [The cat] is a friendly (…) however she is now 12 years old and [the puppy] is very bouncy around her” | |

| Dog’s history | “[The puppy] is complete happy around the cats (…) we think this is because she was raised with cats in the breeder’s household” |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kinsman, R.H.; Owczarczak-Garstecka, S.C.; Casey, R.A.; Da Costa, R.E.P.; Tasker, S.; Murray, J.K. Introducing a Puppy to Existing Household Cat(s): Mixed Method Analysis. Animals 2022, 12, 2389. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12182389

Kinsman RH, Owczarczak-Garstecka SC, Casey RA, Da Costa REP, Tasker S, Murray JK. Introducing a Puppy to Existing Household Cat(s): Mixed Method Analysis. Animals. 2022; 12(18):2389. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12182389

Chicago/Turabian StyleKinsman, Rachel H., Sara C. Owczarczak-Garstecka, Rachel A. Casey, Rosa E. P. Da Costa, Séverine Tasker, and Jane K. Murray. 2022. "Introducing a Puppy to Existing Household Cat(s): Mixed Method Analysis" Animals 12, no. 18: 2389. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12182389

APA StyleKinsman, R. H., Owczarczak-Garstecka, S. C., Casey, R. A., Da Costa, R. E. P., Tasker, S., & Murray, J. K. (2022). Introducing a Puppy to Existing Household Cat(s): Mixed Method Analysis. Animals, 12(18), 2389. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12182389