The Association between Mindfulness and Resilience among University Students: A Meta-Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. The Relationship between Mindfulness and Resilience among University Students

1.2. Rationale and Objectives of the Study

2. Method

2.1. Literature Search and Inclusion Criteria

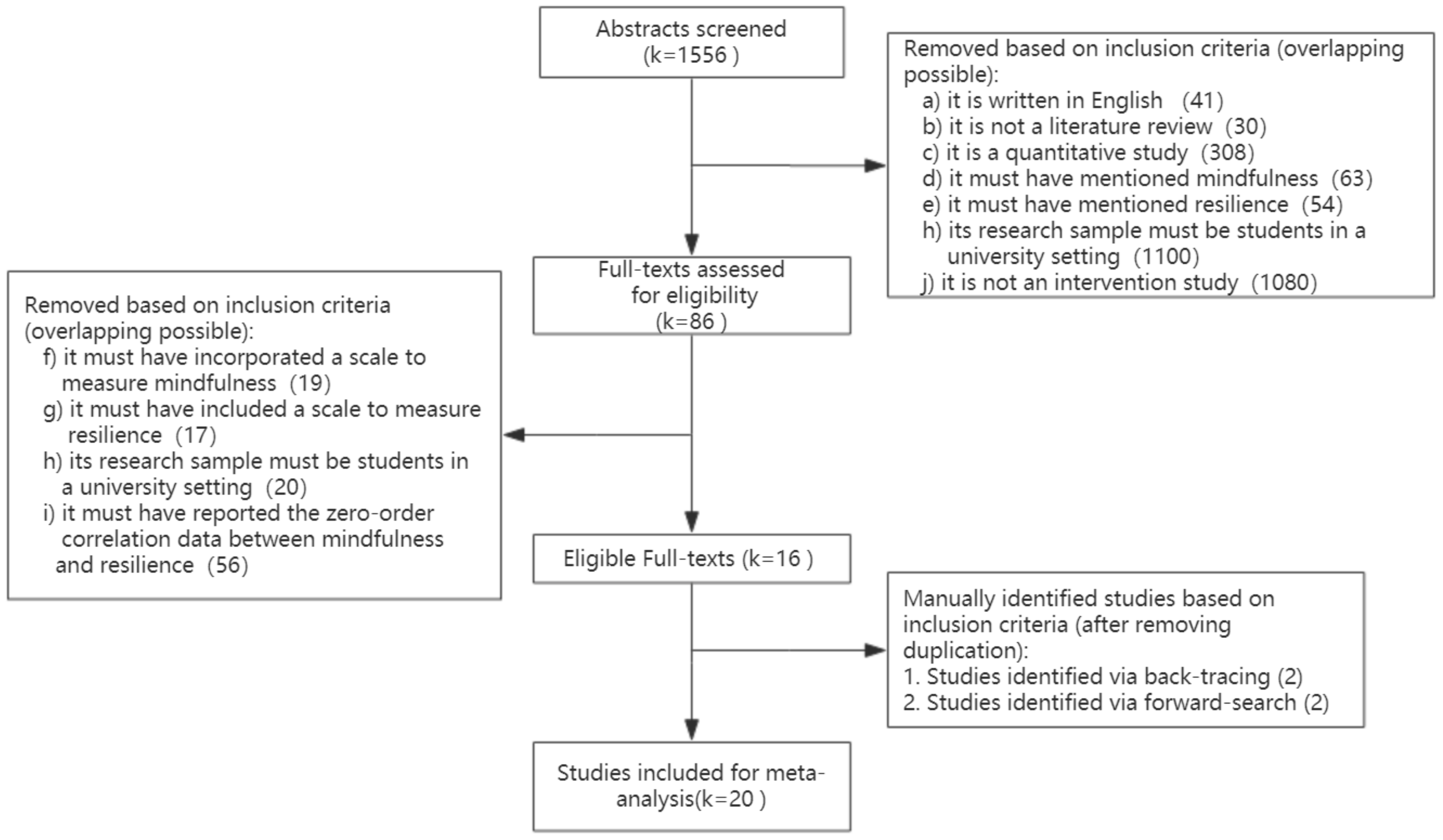

2.2. Literature Selection Process

2.3. Data Coding

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

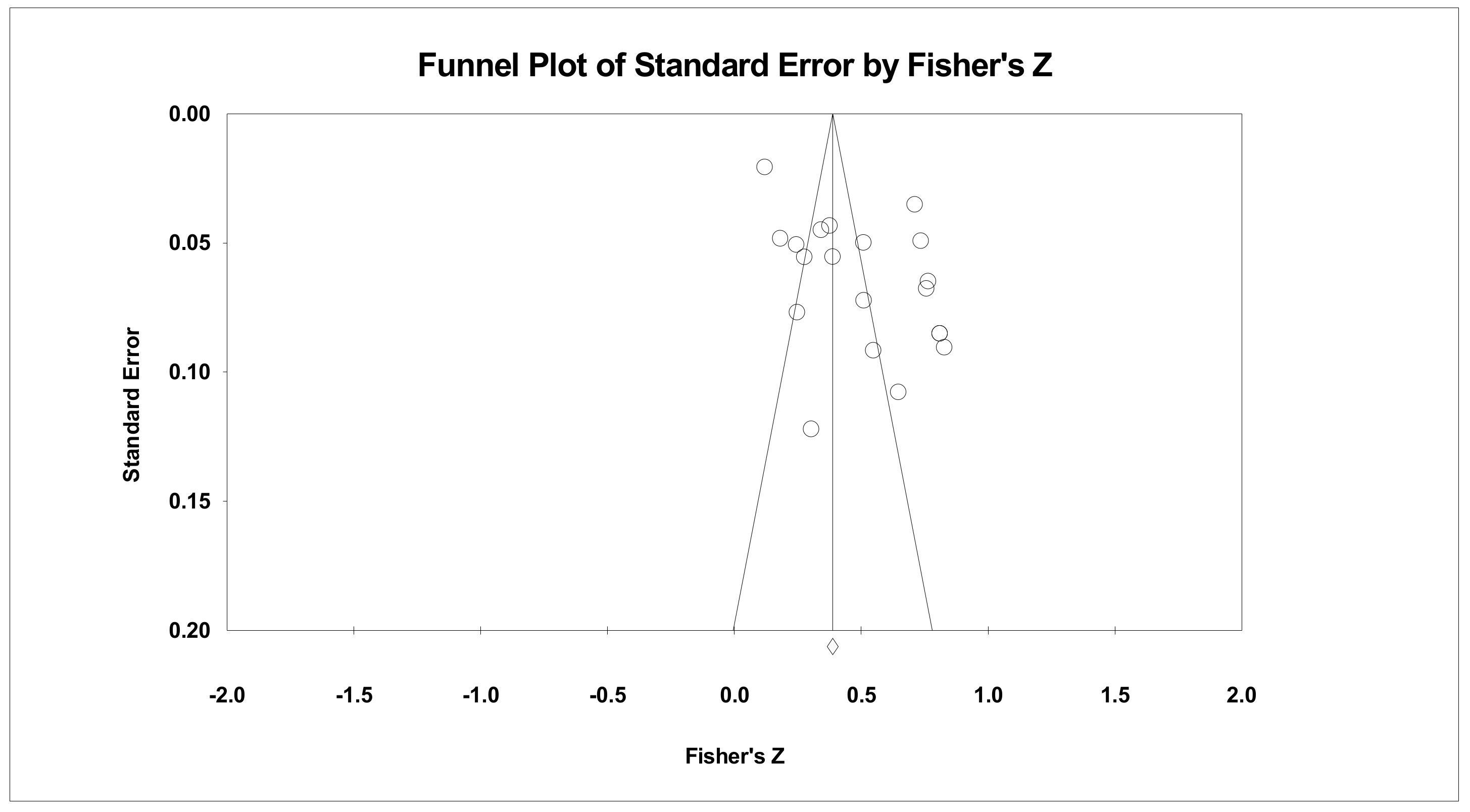

3.2. Publication Bias

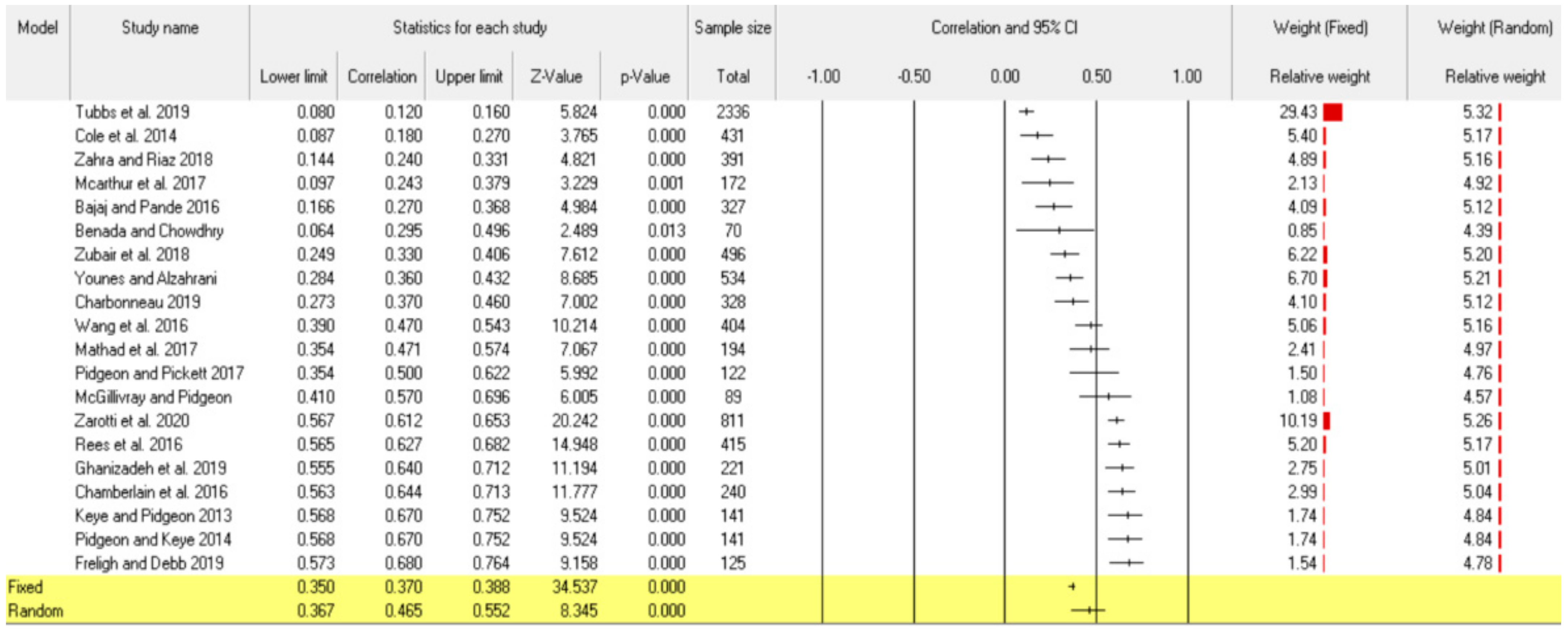

3.3. Analysis of the Overall Effects and Heterogeneity

3.4. Moderator Analysis

3.5. Analysis of Subgroups within the Studies

4. Discussion

4.1. Findings

4.2. Implications of the Findings

4.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tejedor, G.; Segalàs, J.; Barrón, A.; Fernàndez-Morilla, M.; Fuertes, M.T.; Ruiz-Morales, J.; Gutiérrez, L.; García-Gonzàlez, E.; Aramburuzabala, P.; Hernàndez, A. Didactic strategies to promote competencies in sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, E.B. United Nations conference on environment and development. Int. Leg. Mater. 1992, 31, 814–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cebrián, G.; Junyent, M. Competencies in education for sustainable development: Exploring the student teachers’ views. Sustainability 2015, 7, 2768–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrechts, W.; Mulà, I.; Ceulemans, K.; Molderez, I.; Gaeremynck, V. The integration of competences for sustainable development in higher education: An analysis of bachelor programs in management. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 48, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal-Meliá, L.; Estrada, M.; Monferrer, D.; Rodríguez-Sánchez, A. Does Mindfulness Influence Academic Performance? The Role of Resilience in Education for Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Ma, Y.; Li, J.; Cai, Y.; Li, L.; Zhang, J. Mindfulness and psychological distress in kindergarten teachers: The mediating role of emotional intelligence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erus, S.M.; Deniz, M.E. The mediating role of emotional intelligence and marital adjustment in the relationship between mindfulness in marriage and subjective well-being. Pegem J. Educ. Instr. 2020, 10, 317–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teal, C.; Downey, L.A.; Lomas, J.E.; Ford, T.C.; Bunnett, E.R.; Stough, C. The role of dispositional mindfulness and emotional intelligence in adolescent males. Mindfulness 2019, 10, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, S.; Weiss, M.; Newman, A.; Hoegl, M. Resilience in the workplace: A multilevel review and synthesis. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 69, 913–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.; Maritz, A.; Lobo, A. Does individual resilience influence entrepreneurial success? Acad. Entrep. J. 2016, 22, 39–53. [Google Scholar]

- Connor, K.M.; Davidson, J.R.T. Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress. Anxiety 2003, 18, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, A.D.; Bergeman, C.S.; Bisconti, T.L.; Wallace, K.A. Psychological resilience, positive emotions, and successful adaptation to stress in later life. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 91, 730–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahern, N.R.; Kiehl, E.M.; Sole, M.L.; Byers, J. A review of instruments measuring resilience. Issues Compr. Pediatric Nurs. 2006, 29, 103–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, G.E.; Neiger, B.L.; Jensen, S.; Kumpfer, K.L. The resilience model. Health Educ. 1990, 21, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D.; Singer, B. Flourishing under fire: Resilience as a prototype of challenged thriving. In Positive Psychology and the Life Well-Lived; Keyes, C.L.M., Haidt, J., Eds.; APA: Washington, DC, USA, 2003; pp. 15–36. [Google Scholar]

- Hoegl, M.; Hartmann, S. Bouncing back, if not beyond: Challenges for research on resilience. Asian Bus. Manag. 2021, 20, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Wherever You Go, There You Are: Mindfulness Meditation in Everyday Life; Hyperion: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Mindfulness-based intervention in context: Past, present, and future. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2003, 10, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germer, G. What is mindfulness? In Mindfulness and Psychotherapy; Germer, G., Siegel, R., Fulton, P., Eds.; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Baer, R.A.; Smith, G.T.; Hopkins, J.; Krietemeyer, J.; Toney, L. Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment 2006, 13, 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keng, S.; Smoski, M.J.; Robins, C.J. Effects of mindfulness on psychological health: A review of empirical studies. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 31, 1041–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopwood, T.L.; Schutte, N.S. A meta-analytic investigation of the impact of mindfulness-based interventions on post traumatic stress. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 57, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, R.J.; Buttell, F.; Cannon, C. COVID-19: Immediate predictors of individual resilience. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, T.; Heastie, S. High school to college transition: A profile of the stressors, physical and psychological health issues that affect the first-year on-campus college student. Cult. Divers. 2008, 15, 143–147. [Google Scholar]

- Friedlander, L.J.; Reid, G.J.; Shupak, N.; Cribbie, R. Social support, self-esteem, and stress as predictors of adjustment to university among first-year undergraduates. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 2007, 48, 259–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stallman, H.M. Psychological distress in university students: A comparison with general population data. Aust. Psychol. 2010, 45, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gall, T.L.; Evans, D.R.; Bellerose, S. Transition to first-year university: Patterns of change in adjustment across life domains and time. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2000, 19, 544–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reivich, K.; Shatte, A. The Resilience Factor; Broadway Books: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lightsey, O.R. Resilience, meaning, and well-being. Couns. Psychol. 2006, 34, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, B.S.; Gray, J.D.; Nasca, C. Recognizing resilience: Learning from the effects of stress on the brain. Neurobiol. Stress 2015, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, R.J.; Begley, S. The Emotional Life of Your Brain: How Its Unique Patterns Affect the Way You Think, Feel, and Live—And How You Can Change Them; Hudson Street Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Grabbe, L.; Nguy, S.T.; Higgins, M.K. Spirituality development for homeless youth: A mindfulness meditation feasibility pilot. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2012, 21, 925–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.W.; Arnkoff, D.B.; Glass, C.R. Conceptualizing mindfulness and acceptance as components of psychological resilience to trauma. Trauma Violence Abus. 2011, 12, 220–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, S.L.; Brown, K.W.; Biegel, G.M. Teaching self-care to caregivers: Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on the mental health of therapists in training. Train. Educ. Prof. Psychol. 2007, 1, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verplanken, B.; Fisher, N. Habitual worrying and benefits of mindfulness. Mindfulness 2014, 5, 566–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, E.J.; Moldoveanu, M. The construct of mindfulness. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, B.A.; Shapiro, S.L. Mental balance and well-being: Building bridges between Buddhism and western psychology. Am. Psychol. 2006, 61, 690–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roulston, A.; Montgomery, L.; Campbell, A.; Davidson, G. Exploring the impact of mindfulnesss on mental wellbeing, stress and resilience of undergraduate social work students. Soc. Work Educ. 2018, 37, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidic, Z.; Cherup, N. Mindfulness in classroom: Effect of a mindfulness-based relaxation class on college students’ stress, resilience, self-efficacy and perfectionism. Coll. Stud. J. 2019, 53, 130–144. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes, A.T.; Muthukumar, V.; Bhatta, T.R.; Bombard, J.N.; Gangozo, W.J. Promoting resilience among college student veterans through an acceptance-and-commitment-therapy app: An intervention refinement study. Community Ment. Health J. 2020, 56, 1206–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pidgeon, A.M.; Pickett, L. Examining the differences between university students’ levels of resilience on mindfulness, psychological distress and coping strategies. Eur. Sci. J. 2017, 13, 103–113. [Google Scholar]

- Freligh, C.B.; Debb, S.M. Nonreactivity and Resilience to Stress: Gauging the Mindfulness of African American College Students. Mindfulness 2019, 10, 2302–2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McArthur, M.; Mansfield, C.; Matthew, S.; Zaki, S.; Brand, C.; Andrews, J.; Hazel, S. Resilience in veterinary students and the predictive role of mindfulness and self-compassion. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 2017, 44, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, B.; Pande, N. Mediating role of resilience in the impact of mindfulness on life satisfaction and affect as indices of subjective well-being. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2016, 93, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, N.; Hiebert, B. Coping with the transition to post-secondary education. Can. J. Couns. 1996, 30, 93–103. [Google Scholar]

- Lefkowitz, E.S. Things have gotten better: Developmental changes among emerging adults after the transition to university. J. Adolesc. Res. 2005, 20, 40–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubair, A.; Kamal, A.; Artemeva, V. Mindfulness and Resilience as Predictors of Subjective Well-Being among University Students: A Cross Cultural Perspective. J. Behav. Sci. 2018, 28, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Tubbs, J.D.; Savage, J.E.; Adkins, A.E.; Amstadter, A.B.; Dick, D.M. Mindfulness moderates the relation between trauma and anxiety symptoms in college students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2019, 67, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abi-Hashem, N. Resiliency and Culture: An Interdisciplinary Approach. RUDN J. Psychol. Pedagog. 2020, 17, 586–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.W.; Ryan, R.M. The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 822–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walach, H.; Buchheld, N.; Buttenmüller, V.; Kleinknecht, N.; Schmidt, S. Measuring mindfulness-The Freiburg mindfulness inventory (FMI). Personal. Individ. Differ. 2006, 40, 1543–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, G.; Hayes, A.; Kumar, S.; Greeson, J.; Laurenceau, J.P. Mindfulness and emotion regulation: The development and initial validation of the Cognitive and Affective Mindfulness Scale-Revised (CAMS-R). J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2007, 29, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, J.E.; Schmidt, F.L. Methods of Meta-Analysis: Correcting Error and Bias in Research Findings, 2nd ed.; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- White, H.D. Scientific communication and literature retrieval. In The Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis, 2nd ed.; Cooper, H., Hedges, L.V., Valentine, J.C., Eds.; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 51–71. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal, R. The file drawer problem and tolerance for null results. Psychol. Bull. 1979, 86, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, M.; Smith, G.D.; Schneider, M.; Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997, 315, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thompson, S.G.; Deeks, J.J.; Altman, D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina, J.M. Apples and oranges (and pears, oh my!): The search for moderators in meta-analysis. Organ. Res. Methods 2003, 6, 415–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borenstein, M.; Hedges, L.V.; Higgins, J.P.; Rothstein, H.R. Introduction to Meta-Analysis; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.J.; Xu, W.; Luo, F. Emotional Resilience Mediates the Relationship between Mindfulness and Emotion. Psychol. Rep. 2016, 118, 725–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarotti, N.; Povah, C.; Simpson, J. Mindfulness mediates the relationship between cognitive reappraisal and resilience in higher education students. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2020, 156, 109795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanizadeh, A.; Makiabadi, H.; Navokhi, S.A. Relating EFL University Students’ Mindfulness and Resilience to Self-Fulfilment and Motivation in Learning. Issues Educ. Res. 2019, 29, 695–714. [Google Scholar]

- Younes, M.S.; Alzahrani, M.R. Could Resilience and Flourishing be Mediators in the Relationship between Mindfulness and Life Satisfaction for Saudi College Students? A Psychometric and Exploratory Study. J. Educ. Psychol. Stud. [JEPS] 2018, 12, 708–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.T.; Riaz, S. Mindfulness and resilience as predictors of stress among university students. J. Postgrad. Med. Inst. 2018, 32, 378–385. [Google Scholar]

- Mathad, M.D.; PraDhan, B.; Rajesh, S.K. Correlates and predictors of resilience among baccalaureate nursing students. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. JCDR 2017, 11, JC05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benada, N.; Chowdhry, R. A Correlational Study of Happiness, Resilience and Mindfulness among Nursing Student. Indian J. Posit. Psychol. 2017, 8, 105–107. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain, D.; Williams, A.; Stanley, D.; Mellor, P.; Cross, W.; Siegloff, L. Dispositional mindfulness and employment status as predictors of resilience in third year nursing students: A quantitative study. Nurs. Open 2016, 3, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, C.S.; Osseiranmoisson, R.; Chamberlain, D.; Cusack, L.; Anderson, J.; Terry, V.; Hegney, D. Can We Predict Burnout among Student Nurses? An Exploration of the ICWR-1 Model of Individual Psychological Resilience. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, N.N.; Nonterah, C.W.; Utsey, S.O.; Hook, J.N.; Hubbard, R.R.; Opare-Henaku, A.; Fischer, N.L. Predictor and moderator effects of ego resilience and mindfulness on the relationship between academic stress and psychological well-being in a sample of Ghanaian college students. J. Black Psychol. 2014, 41, 340–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pidgeon, A.M.; Keye, M. Relationship between resilience, mindfulness, and pyschological well-being in University students. Int. J. Lib. Arts Soc. Sci. 2014, 2, 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Keye, M.; Pidgeon, A.M. An Investigation of the Relationship between Resilience, Mindfulness, and Academic Self-Efficacy. Open J. Soc. Sci. 2013, 1, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charbonneau, D. Model of mindfulness and mental health outcomes: Need fulfillment and resilience as mediators. Can. J. Behav. Sci. /Rev. Can. Des Sci. Du Comport. 2019, 51, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGillivray, C.; Pidgeon, A.M. Resilience attributes among university students: A comparative study of psychological distress, sleep disturbances and mindfulness. Eur. Sci. J. 2015, 11, 33–48. [Google Scholar]

- Pirson, M.; Langer, E.J.; Bodner, T.; Zilcha-Mano, S. The development and validation of the Langer mindfulness scale-enabling a socio-cognitive perspective of mindfulness in organizational contexts. In Fordham University Schools of Business Research Paper; SSNR: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, B.W.; Dalen, J.; Wiggins, K.; Tooley, E.; Christopher, P.; Bernard, J. The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2008, 15, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, W.Y.; Kim, M.G.; Kim, J.H. Developing measures of resilience for Korean adolescents and testing cross, convergent, and discriminant validity. Stud. Korean Youth 2009, 20, 105–131. [Google Scholar]

- Reivich, K.; Shatte, A. The Resilience Factor: 7 Keys to Finding your Inner Strength and Overcoming Life's Hurdles; Harmony: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wagnild, G.; Young, H. Resilience: Analysis and measurement. Gerontologist 1990, 30, 267–280. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Lv, J.-M. A research on influencing factors of adolescent emotional resilience. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 34, 593–597. [Google Scholar]

- Block, J.; Kremen, A.M. IQ and ego-resiliency: Conceptual and empirical connections and separateness. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 70, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell-Sills, L.; Stein, M.B. Psychometric analysis and refinement of the connor–davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC): Validation of a 10-item measure of resilience. J. Trauma. Stress Off. Publ. Int. Soc. Trauma. Stress Stud. 2007, 20, 1019–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinn-Nilas, C. Self-reported trait mindfulness and couples’ relationship satisfaction: A meta-analysis. Mindfulness 2020, 11, 835–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dam, N.T.; Earleywine, M.; Borders, A. Measuring mindfulness? An item response theory analysis of the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2010, 49, 805–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Strauss, C.; Crane, C.; Barnhofer, T.; Karl, A.; Cavanagh, K.; Kuyken, W. Examining the factor structure of the 39-item and 15-item versions of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire before and after mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for people with recurrent depression. Psychol. Assess. 2016, 28, 791–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baer, R.A.; Smith, G.T.; Lykins, E.; Button, D.; Krietemeyer, J.; Sauer, S.; Williams, J. Construct validity of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire in meditating and nonmeditating samples. Assessment 2008, 15, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weilgosz, J.; Schuyler, B.S.; Lutz, A.; Davidson, R.J. Long term mindfulness training is associated with reliable differences in resting respiration rate. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 27533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study Name | Mindfulness Measures | Resilience Measures | Country | Culture | Development Level | Dimensions of Mindfulness | Sample Size | r |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zarotti et al. [61] | FFMQ | BRS | UK | West | Developed | 811 | 0.612 | |

| Ghanizadeh et al. [62] | LMS | L2 RS | Iran | East | Developing | 221 | 0.64 | |

| Younes and Alzahrani. [63] | MAAS | BRS | Kingdom of Saudi Arabia | East | Developing | 534 | 0.36 | |

| Zahra and Riaz [64] | FFMQ | CD-RISC | Pakistan | East | Developing | 391 | 0.24 | |

| Zubair et al. [47] | MAAS | ERS | Pakistan and Russia | / | / | 496 | 0.33 | |

| Pidgeon and Pickett. [41] | FMI | RFI | Australian | West | Developed | 122 | 0.5 | |

| Mathad et al. [65] | FMI | CD-RISC-10 | India | East | Developing | 194 | 0.471 | |

| Benada and Chowdhry [66] | MAAS | RS | India | East | Developing | 70 | 0.295 | |

| Chamberlain et al. [67] | CAMS-R | CD-RISC-10 | Australian | West | Developed | 240 | 0.644 | |

| Bajaj and Pande. [44] | MAAS | CD-RISC-10 | India | East | Developing | 327 | 0.27 | |

| Wang et al. [60] | FFMQ | AERQ | China | East | Developing | 404 | 0.47 | |

| Observing | 0.05 | |||||||

| Describing | 0.3 | |||||||

| Acting with awareness | 0.43 | |||||||

| Nonjudgmental | 0.09 | |||||||

| Non-reacting | 0.39 | |||||||

| Rees et al. [68] | CAMS-R | CD-RISC-10 | Australia | West | Developed | 415 | 0.627 | |

| Cole et al. [69] | MAAS | ERS | Ghana | / | / | 431 | 0.18 | |

| Pidgeon and Keye [70] | FMI | CD-RISC | Australia | West | Developed | 141 | 0.67 | |

| Keye and Pidgeon [71] | FMI | CD-RISC | Australia | West | Developed | 141 | 0.67 | |

| Mcarthur et al. [43] | FFMQ | BRS | Australian | West | Developed | 172 | 0.243 | |

| Observing | 0.157 | |||||||

| Describing | 0.045 | |||||||

| Acting with awareness | 0.264 | |||||||

| Nonjudgmental | 0.339 | |||||||

| Non-reacting | 0.412 | |||||||

| Freligh and Debb. [42] | FFMQ | BRS | America | West | Developed | 125 | 0.68 | |

| Observing | 0.09 | |||||||

| Describing | 0.74 | |||||||

| Acting with awareness | 0.78 | |||||||

| Nonjudgmental | 0.66 | |||||||

| Non-reacting | 0.56 | |||||||

| Tubbs et al. [48] | MAAS | America | West | Developed | 2336 | 0.12 | ||

| Charbonneau. [72] | MAAS | BRS | Canada | West | Developed | 328 | 0.37 | |

| McGillivray and Pidgeon. [73] | FMI | RS | Australian | West | Developed | 89 | 0.57 |

| K | R | 95% CI | Within-Group Heterogeneity | Test for Subgroup Difference (Random Effect) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | Qw | p | I2 | Qb | df | p | |||

| Mindfulness scale | 22.167 | 4 | 0.000 | |||||||

| FFMQ | 5 | 0.467 | 0.341 | 0.576 | 82.680 | 0.000 | 95.162 | |||

| FMI | 5 | 0.582 | 0.466 | 0.678 | 11.962 | 0.018 | 66.560 | |||

| MAAS | 7 | 0.275 | 0.154 | 0.387 | 54.780 | 0.000 | 89.047 | |||

| CAMS-R | 2 | 0.635 | 0.474 | 0.755 | 0.122 | 0.726 | 0.000 | |||

| Other | 1 | 0.640 | 0.395 | 0.800 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | |||

| Resilience scale | 2.882 | 5 | 0.718 | |||||||

| BRS | 5 | 0.469 | 0.286 | 0.619 | 70.040 | 0.000 | 94.289 | |||

| CD-RISC-10 | 4 | 0.517 | 0.321 | 0.671 | 48.860 | 0.000 | 93.860 | |||

| CD-RISC | 4 | 0.447 | 0.236 | 0.618 | 118.443 | 0.000 | 97.467 | |||

| ERS | 2 | 0.257 | -0.071 | 0.535 | 5.927 | 0.015 | 83.129 | |||

| RS | 2 | 0.446 | 0.115 | 0.688 | 4.443 | 0.035 | 77.494 | |||

| Other | 3 | 0.541 | 0.315 | 0.709 | 8.924 | 0.012 | 77.590 | |||

| Culture | 1.389 | 1 | 0.239 | |||||||

| E | 7 | 0.403 | 0.201 | 0.571 | 50.069 | 0.000 | 88.017 | |||

| W | 11 | 0.536 | 0.397 | 0.651 | 419.949 | 0.000 | 97.619 | |||

| Development level | 1.389 | 1 | 0.239 | |||||||

| Developing | 7 | 0.403 | 0.201 | 0.571 | 50.069 | 0.000 | 88.017 | |||

| Developed | 11 | 0.536 | 0.397 | 0.651 | 419.949 | 0.000 | 97.619 | |||

| Dimensions of Mindfulness | k | r (Fixed Effect) | 95% CI | Within-Group Heterogeneity | Test for Subgroup Difference (Random Effect) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | Qw | p | I2 | Qb | Df | p | |||

| 4.993 | 1 | 0.288 | ||||||||

| Acting with awareness | 3 | 0.475 | 0.416 | 0.531 | 45.644 | 0.00 | 95.618 | |||

| Nonjudgmental | 3 | 0.271 | 0.201 | 0.339 | 47.420 | 0.00 | 95.787 | |||

| Non-reacting | 3 | 0.428 | 0.365 | 0.487 | 4.652 | 0.098 | 57.008 | |||

| Observing | 3 | 0.083 | 0.009 | 0.157 | 1.400 | 0.497 | 0.00 | |||

| Describing | 3 | 0.343 | 0.276 | 0.407 | 60.332 | 0.00 | 96.684 | |||

| Test for Subgroup Difference (Random Effect) | Dimensions of Mindfulness | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA | NR | D | NJ | AA | NJ | NR | NJ | NR | NJ | |

| O | O | O | O | D | D | D | AA | AA | NR | |

| Qb | 5.916 | 29.285 | 2.082 | 2.220 | 0.277 | 0.006 | 0.073 | 0.419 | 0.204 | 0.181 |

| df | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| p | 0.015 | 0.000 | 0.149 | 0.136 | 0.599 | 0.937 | 0.787 | 0.517 | 0.651 | 0.671 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, Z. The Association between Mindfulness and Resilience among University Students: A Meta-Analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10405. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610405

Liu X, Wang Q, Zhou Z. The Association between Mindfulness and Resilience among University Students: A Meta-Analysis. Sustainability. 2022; 14(16):10405. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610405

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Xuepeng, Qing Wang, and Zhenzhen Zhou. 2022. "The Association between Mindfulness and Resilience among University Students: A Meta-Analysis" Sustainability 14, no. 16: 10405. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610405

APA StyleLiu, X., Wang, Q., & Zhou, Z. (2022). The Association between Mindfulness and Resilience among University Students: A Meta-Analysis. Sustainability, 14(16), 10405. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610405