1. Introduction

Taxes are essential to foster economic growth and development. Understanding the taxes and having the right approach towards them can make a massive difference between the success and failure of businesses [

1,

2]. Each business has its specific requirements for the tax system, depending upon its business activity, size, location, form, and nature. Businesses are often unaware of their tax obligations, which affects their operating and financial decisions [

3]. Firms can attempt to reduce this impact through proper tax planning, which is possible with tax knowledge [

4].

Tax knowledge is an important contributing factor as it helps businesses adhere to tax rules and regulations. Understanding the tax requirements as per their nature of business (manufacturing and servicing) might influence their business strategies. A survey from 147 economies identified low tax awareness and knowledge as the biggest constraint for business operations [

5]. Further, the study by Aruna [

6] stated that businesses faced problems in their operations as low tax knowledge led to complexities and unorganized administrative costs [

7]. A study by Konstantin [

8] pointed out that firms with low tax awareness often get trapped by insolvent traders, leading to illegal refund scams [

9]. Loo [

10]; Loo, Mckerchar, and Hansford [

11,

12] emphasized that businesses in Malaysia and Australia with low tax knowledge suffered heavy losses due to tax fines that occurred because of tax non-compliance. Therefore, policymakers and governments want that firms must be aware of the taxation system, its rules, and its regulations. It would lead to timely tax compliance, generation of revenue, increased business efficiency, and reduction in tax scams.

To conduct the present research, we have opted for India—one of the world’s developing countries. On 1 July 2017, India reformed its indirect tax structure by implementing Goods and Service Tax (GST). Since GST is technology-led tax reform, a paradigm shift has been observed in the compliance processes, which are carried through online portals, leading to digitalization in businesses [

13,

14]. The OECD [

15] emphasized that developing countries are adopting the new technological tax filing system, for which proper training, skill, and expert knowledge are required. Therefore, it becomes essential to study the impact of technological advancement in the tax system along with the tax knowledge after the tax reform. The present research was conducted with two primary objectives:

- O1

To examine the impact of tax knowledge on business performance.

- O2

To examine the impact of a technological shift in the tax system on business performance.

The present paper aims to analyze the effect of tax knowledge and technological advancement on the business performance of micro, small and medium enterprises. It is crucial to study the impact on MSME businesses as they are likely to be more hesitant to adopt a new taxation policy and its proper compliance due to its high administrative costs [

16]. They struggle to keep pace with new tax laws, changing tax rates, regulations, and technological advancement due to their limited economies of scale, low resources, and insufficient tax knowledge [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. Furthermore, MSMEs are the levers for socio-economic development and constitute most businesses [

19]. They are the most potential firms that may eventually grow into larger firms. However, they are the most overlooked and under-researched enterprises despite the plausible benefits they provide. Therefore, the present research examines the impact on the MSMEs’ business performance. Moreover, Indian MSMEs contribute around 28.77% to the country’s GDP, 95% of industrial output, 45% of production, and 48.10% of exports, and provide employment opportunities (11.09 million opportunities) (MSME, Annual Report, 2020–2021).

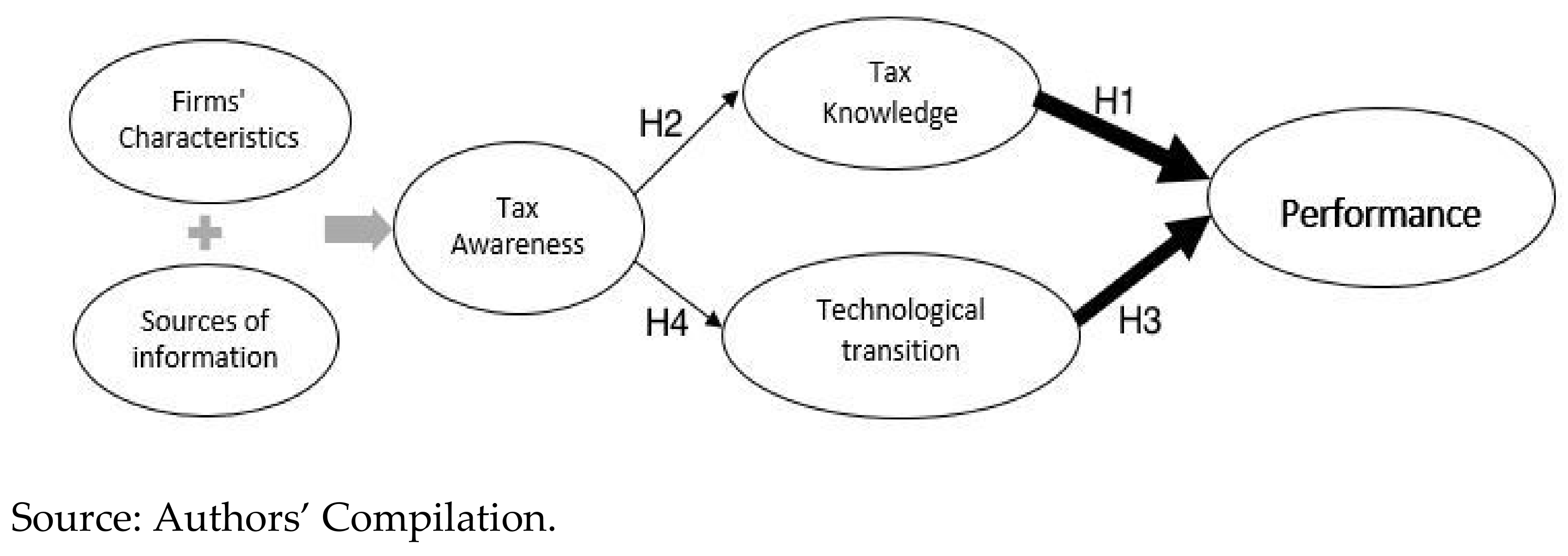

In order to achieve the objectives of the study, we have developed a path model using Partial Least Square Structured Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). The path model highlighted three key findings. Firstly, tax knowledge and technological advancement in the tax system enhanced the business’ operational efficiencies and flow of funds. Secondly, a significant effect of tax awareness level is observed on tax knowledge and the technological shift, which highlighted that the training sessions, workshops, and seminars on the tax system enable the firms to handle tax matters on time. Thirdly, the model revealed a strong association between firms’ characteristics (size, turnover, and legal stature) and tax awareness levels. The association depicts that each business has specific requirements for the tax system, depending upon their business activity, size, and nature, for which proper awareness is required as it influences performance. The comprehensive research and the results on Indian MSMEs may help other countries to understand the determinants of tax awareness and knowledge impacting their businesses.

The paper is organized into the following parts—

Section 2 reviews the existing literature and the hypothesis. Then, the materials and methods used are provided in

Section 3. Next, statistical properties are provided in

Section 4, followed by empirical findings of the study in

Section 5. Finally, the discussion and conclusion are elaborated in

Section 6, followed by the practical implications in

Section 7.

2. Review of Literature and Hypothesis Development

A review of past research lays a strong foundation for any new study. It provides a robust research base that helps identify the research problems, questions, and feasible objectives and constructs for the study [

23,

24]. The literature gives insight into tax knowledge, technological advancement, tax awareness, tax information sources, and firms’ characteristics. The relationship between business and the above determinants helped formulate the study’s hypothesis.

2.1. Tax Knowledge

Tax knowledge implies a thorough understanding of the tax system’s rules and regulations formulated by the government. The three major elements identified regarding tax knowledge are general, procedural, and legal tax knowledge [

20]. General tax knowledge compromises fiscal cognizance; procedural knowledge refers to understanding tax compliance procedures; legal knowledge comprises rules and regulations.

General tax knowledge proposes the willingness to abide by tax laws, which is why taxpayers comply with taxation rules, and failure to do so might land the businesses into critical situations (Theory of Reasoned Action). Tax non-compliance, either due to insufficient tax knowledge or willfully, might lead to heavy fines and penalties that hamper the firm’s profitability and reputation [

25]. Therefore, tax knowledge is considered one of the key drivers determining the firms’ performance [

26,

27].

Procedural Tax knowledge refers to the skills and resources to maintain tax records on time [

28]. It helps taxpayers maintain the required tax records and adhere to their responsibilities on time. Tax knowledge plays a pivotal role in preventing the afraid reaction toward tax changes and the tax system and is directly associated with enhancing tax compliances in businesses [

29,

30,

31,

32]. Firms find it hard to sustain themselves in a complex corporate tax environment and adapt to subsequent changes without proper tax knowledge [

33,

34,

35,

36]. Proper knowledge of compliance procedures, new tax rules, rates, and exemption lists, has shown a remarkable positive effect on the firm, economy, and its businesses in the long run due to its lawful compliance [

37,

38,

39,

40].

Legal knowledge refers to understanding how one is taxed [

28]. It has two dimensions; one is understanding legal terms and legislation (knowing that something is taxable), and the second is the ability to apply the legal knowledge to specific situations to be able to calculate the tax effect (knowing how) [

41]. Bornman and Ramutumbu [

20] specify that legal tax knowledge includes a ‘broad understanding of legal terminologies’ and ‘the ability to accurately apply specific rules and regulations to determine [one’s] tax liability. Tax knowledge enables businesses to understand the applicable tax rates and rules as per their nature, which leads to ease in operations [

39,

40].

Accordingly, we hypothesize:

H1. Tax knowledge positively impacts MSMEs’ performance.

Tax knowledge demands proper awareness of the tax system and the frequent changes. There is a thin line between awareness and knowledge. Awareness implies being conscious of the events occurring and perceiving things, whereas knowledge implies having detailed information, knowing the facts, and having a thorough understanding of the subject (theoretically and practically). For any tax reform to be implemented and adopted, people’s readiness is required as the willingness to adopt and implement the reforms has benefited the economies and businesses in terms of increased revenue [

42,

43,

44] (Theory of Planned Behavior). Tax awareness is a state where a taxpayer knows, accepts, and complies with the implemented tax regulations and desires to comply with tax obligations [

45,

46]. Therefore, formal training sessions, discussions, talks, seminars, workshops, and software skills encouraged retailers, traders, business owners, and tax consultants to adjust to the reforms [

42,

47]. A similar perception was observed in India [

43,

44]. MSME owners are very much interested in gaining knowledge about the working process of GST by joining training sessions, conferences, group discussions, and seminars rather than redressing grievances by using Consumer Protection Law [

48,

49]. The government’s initiatives on spreading tax awareness have increased the acceptance level of new reform without resistance in businesses, especially in small and micro enterprises [

50,

51]. The study by Wang and Kesan [

52] in China quantified that SMEs are very sensitive to innovations as they are not the early adopters of new tax reforms compared to large firms [

53]. Jalaja [

54] empirically verified that proper training and knowledge of the changed tax system by the government helped ease the adaption constraint.

Accordingly, we hypothesize:

H2. Tax awareness positively influences tax knowledge.

2.2. Technological Transition in the Tax System

Digital tax administration has emerged as one of the biggest drivers of tax function transformation in 2017, with GST being the leading technology-led tax reform necessitating a business transformation. Institutional factors such as registration and filing of returns have been replaced by e-filing to lessen the burden and prevent fraud in many countries [

7]. The aim of technological advancement in tax reform lies in the simplification of the tax system. Proper tax compliance and good tax administration can be carried out with the help of technology [

55]. Moreover, I.T. helped organizations sustain operational efficiencies by enabling paperless compliances, saving their productive time [

56].

As per the Economic Survey of 2018–2019, the use of technology in the tax system enables e-filing of tax returns, efficient investigation, and performance analysis. It benefits both the Government and enterprises in curbing tax evasion and ease of compliance, respectively [

57,

58]. Technology in the tax system has resolved many business issues, such as corruption, privacy, and public/private partnerships costs [

55,

59]. I.T. in the tax system led to easy mobility of funds [

60].

Accordingly, we hypothesize that:

H3. Technology transition for tax system positively impacts MSMEs’ performance.

The technological tax transition demands proper awareness for its smooth working and implementation in businesses. Technology is crucial in tax compliance as it forms the backbone of any taxation policy [

61,

62]. However, at the same time, technology readiness is an equally important issue. Malaysian study showed considerable discomfort at the start with the technology of new tax reform [

63]. In order to eradicate the uneasiness and smooth working of new digital platforms in businesses, proper awareness is required. A solid fundamental understanding of the taxation system, essential skills, and education in Information Communication Technology (ICT) are required for the adaptation of technological advancements by SMEs [

64]. In the past, it was noticed that owners lacked technical know-how competency. Owners must first learn and enhance their skills to support the staff [

65]. Attitude plays a vital role in adopting the new electronic tax system and tax compliance [

66].

MSMEs often face problems with new technology and tax reforms. Wang and Kesan’s [

52] study in China quantified that SMEs are very sensitive to innovations. Small/medium-sized firms are not the early adopters of new technology at times of new tax reforms, whereas large firms embrace e-compliances [

53]. Similar implications are observed during the pandemic times in small firms of developing economies that slow technological transition hampered their operational performance [

67]. The study was performed in Uganda by Asianzu and Maiga [

68] poised that a new e-tax system used by large and small companies finds it challenging to comply with due to lack of awareness and knowledge. Accordingly, we hypothesize:

H4. Tax awareness leads to the smooth adaption of technological transition among MSMEs.

2.3. Studies Related to Factors Impacting Tax Awareness Level

2.3.1. Firms’ Characteristics

In the area of micro and small business research, the presence of economies of scale strongly implies that firms’ characteristics (size, type, and turnover) are one of the essential factors in assessing their performance [

69,

70,

71,

72]. The policy changes directly impact the firms’ performance [

73,

74] as every business has unique characteristics, and the awareness level should be according to its legal form, size, and nature. The study by Hayaningsh and Abao [

75] stressed that the level of awareness in paying taxes is directly related to taxpayers’ cultural, social, and economic characteristics. In the case of businesses, these are their firms’ characteristics, such as line of business, the form of business, sales, income level, tax returns, and legal entity [

76]. Therefore, it becomes essential to examine their association with awareness level.

2.3.2. Information Sources

Sharing of tax information has always been a crucial matter for policymakers globally and internationally. To promote global financial transparency and awareness at the national level, the exchange of tax information is vital. Data analysts at the global level [

77] and mass media (tax journals, books, newspapers, internet) at the national have been the source of information to spread awareness [

78,

79,

80]. Studies in developing countries such as Malaysia [

81] stated that information about new tax rules and regulations is provided through public lectures and seminars to help spread tax awareness. Tax awareness helps narrow the negative perception about the tax system and helps in lawful tax compliance [

82].

2.4. Research’ Conceptual Model

Based on the detailed literature review in

Section 2, we developed a conceptual model (

Figure 1) for our study. The conceptual model reflects the relationships in different determinants related to tax knowledge, tax awareness, technological adoption, and their impact on performance.

3. Materials and Methods Used

The study’s objective is to examine the impact of tax knowledge and technological transition in the tax system on the business performance of MSMEs. First, the sampling techniques applied to collect the data are explained in the first sub-

Section 3.1. Then, the data constructs used and their measures are explained in the second sub-

Section 3.2. Later the methodology applied to analyze the data is discussed in the third sub-

Section 3.3.

3.1. Sample

This section has discussed the data and sample used for the study. We have collected primary data with a structured questionnaire from the MSMEs in India to study the impact of tax reforms (GST) on their performance. In addition, a pilot survey was conducted for 15 senior academicians, and 15 practitioners specializing in business performance and tax reforms, and modifications to the questionnaire were made as per the feedback.

The population units, which are MSMEs in India, are diverse. MSME has clusters across different states with specified benefits provided to them. Due to this, we have selected one of the states, Punjab in India (India administratively is divided into 29 States and 7 Union Territories. Punjab is one state of India. Punjab has a strong base of more than 2 lac small-scale units. These have shown high growth in the recent past, with value of production increasing at the rate of 12% on average between 2015–2016 and 2017–2018. During 2017–2018, the number of MSME units increased by 26,683. The total number of medium and large industrial units in Punjab is 504. The MSME industry sector contributes 25%, and service sector contributes 46.7% of Gross State Value Added (GSVA). Source: Punjab Economic Survey, 2019–2020; Economic and Statistical Organization, Department of Planning, Government of Punjab; website:

www.esopb.gov.in accessed on 28 June 2022) for our study and further applied two-stage sampling techniques to MSMEs registered in this state. In the first stage, we divided the population into three strata—micro, small, and medium based on the definition of the MSMED Act 2006. The definition describes these enterprises’ size based on their investments in plants and machinery. For micro-sized firms, the threshold limit for the investment in plant and machinery is up to INR 2.5 million; for small-size firms, the limit is above INR 2.5 million but up to INR 50 million; for medium-size, the limit is above INR 50 million. Then, in the second stage, we applied a proportionate random sampling technique to each stratum. The final sample consisted of 450 responses in total, which are 44% micro units (197); 45% small (202), and 11% medium enterprises (51).

3.2. Survey Instrument and Data

In this section, data collected through the self-structured questionnaire are explained. The questionnaire was administered to 700 units during the canvassing period from August 2019 to August 2020 by various means. We received a response from 470 units leading to a response rate of 67%. The respondents were owners, managers, or experts managing the firm’s tax affairs. These tax personnel is targeted to access their tax knowledge after the tax reform because they play a crucial role in investment decisions, financing, strategic planning, tax planning, and structuring policies for their firms [

83,

84]. In the editing stage, 20 responses were eliminated due to non-response in one or a few items.

The dependent variable for the study is business performance. The independent variables are GST factors, namely, tax awareness, tax knowledge, and technological transition for the tax system (based on the discussion in

Section 2). Further, the effect of firms’ characteristics and information sources are taken on the tax awareness level. The details for each variable are described below in

Table 1:

3.3. Methodology

Partial Least Square Structured Equation Modeling is applied in the present study. Based on literature and the conceptual model, as discussed in

Section 2 and

Section 3, we formulated a functional model where the business performance is considered as a function of tax knowledge and technological transformation in the tax system, represented in Equation (1) below:

where Tax knowledge is the combination of legal and procedural tax knowledge. Legal tax knowledge implies the dual GST model for MSMEs—Central GST and State GST; applicable tax rates and e-way bills for MSMEs. Procedural tax knowledge here is the knowledge about GST compliances for MSMEs; scope of taxable items and exemption list for MSMEs (Source: Central Goods and Services Act 2017 [

99] and Borman and Ramutumbu (2019) [

20]). Further, technological transformation is the combination of different factors as stated below:

Further, the literature also defines the relationship between tax awareness, tax knowledge and technological transition in the tax system, which is stated below:

where,

Here, we wish to establish the path wherein we can study the effect of each variable in Equation (1) on business performance. For this, we applied Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM) as the PLS-SEM has three major advantages over traditional multivariate techniques—(i) detailed assessment of measurement of error; (ii) estimation of the latent variable via observed variable; iii) model testing where a structure can be imposed and assessed as to fit of the model [

100,

101]. SEM is broadly used in social science research as it can build a model using multiple latent variables by considering various measurement errors [

102]. The measurement model helps to decide the scales’ properties, and the structural model establishes the relationships among the variables.

We applied Smart PLS 3.2.0 [

101,

102] to compute the path model for our functional model shown in Equations (1) and (4). This PLS-SEM model will help to develop a path model to evaluate the impact of tax knowledge and technological advancements on business performance while considering the effect of each latent variable on tax awareness, information sources, and firms’ characteristics.

4. Statistical Properties of Model

The present paper has employed a Partial Least Square Structured Equation Model (PLS-SEM) with SmartPLS 3.0 to measure the impact on business performance. This section provides findings on SEM’s statistical properties, namely reliability, discriminant validity, and variance analysis.

This section provides the model’s statistical tests and properties to ensure reflective constructs’ internal reliability and validity.

Table 2 depicts the internal reliability for business performance, firm characteristics, and various GST factors. The composite reliability [

103] and Cronbach alpha values are above the lower limit of 0.70 [

102]. The present values of Cronbach alpha lie between 0.705–0.864, and composite reliability values lie from 0.802 to 0.909 (

Table 2). Thus, the given values of the constructs reflect the good internal reliability of the model.

Factor loadings and average variance extracted (AVE) are used to examine constructs’ convergent validity [

104]. The value of factor loadings and average variance extracted (AVE) should exceed the minimum requirement of 0.50 [

105] for the explained variance to be greater than the measurement error. In the present study, AVE is between 0.509–0.769 (

Table 2). The average variance extracted (AVE) for all constructs is higher than the critical threshold value of 0.50. Factor loadings of the items on their respective constructs are greater than 0.6. This lends support to the measures’ convergent validity.

The discriminant validity [

104] was measured by comparing the values of the square root of AVE. It is recommended that the value of the square root of AVE should be larger than the inter-construct correlations [

101,

102], as stated in

Table 3. The results confirm that the reflective construct exhibits discriminant validity. Later, the Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio measures similarity between latent variables. It is less than the threshold value of 0.9 for all the constructs, illuminating the model’s discriminant validity.

The next step was to check the Outer and Inner Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). VIF values are presented in

Table 4. As highlighted, outer and inner VIF values are less than five and in the acceptable range [

101,

102]. Thus, collinearity is low, as indicated by a VIF value (lower than 5). Hence no indicator was removed.

5. Empirical Findings

The study examined the impact of tax knowledge and technological transition in the tax system on MSMEs’ business performance. The PLS-SEM model (

Figure 2) and Bootstrap model (

Appendix A) depict a positive impact of tax knowledge and technological shift on the MSMEs’ performance level. The designed PLS-SEM model is able to explain a total of 60.3% of the variation.

Equation (1) formulated in

Section 3 can be written as:

Table 5 states the path coefficient results for the path model developed for analyzing the impact of tax knowledge and technological transition on performance. The reflective model is used in the present study depicting that the construct causes the measurement of indicator variables. The magnitude of R

2 and adjusted R

2 values (

Table 5) states that the PLS-SEM model can predict the impact significantly on business performance (R

2: 0.603; adjusted R

2: 0.595).

The structural measurement model evaluates firms’ characteristics, and information sources positively correlate with GST awareness at a 1% significant level (p-value < 0.000). The direct path coefficient for firms’ characteristics is 0.222 (t-statistic 3.231), and the outer loadings suggest different types (0.836), turnover (0.785), and forms (0.753) of MSMEs highly influence the tax awareness level. Likewise, the sources of information have shown a positive association with GST awareness levels. The direct path coefficient for information sources is 0.515 (t-statistic 6.459; p-value < 0.000). The most influential factor portrayed through the survey that enriches the awareness level is the tax experts (loading value 0.823) and the internet also provides the latest updates regarding new tax amendments, FAQs, seminars, workshops, and training programs to be held on GST (loading value 0.847).

GST awareness level positively impacts the tax knowledge (β-value: 0.528; t-statistics 7.795;

p-value < 0.000) and adaption of technological transition (β-value 0.391; t-statistics 3.913;

p-value < 0.000) among MSMEs, as stated in

Table 5. The results and higher outer loading values (

Figure 2) supported that proper technical tax know-how (0.796); tax agent services (0.760), and tax seminars and workshops (0.757) conducted by government and private institutions have helped to enhance the tax knowledge and led to the technological adaption of the tax change in MSMEs. This signifies acceptance of the hypothesis,

H2: Tax awareness positively influences tax knowledge, and H4: Tax awareness leads to the smooth adaption of technological transition among MSMEs.

Knowledge about the taxation system advances to smooth implementation of reform in the business. The legal and procedural tax knowledge plays an important role in impacting the performance (β-value 0.252; t-statistics 3.261; p-value < 0.000). The knowledge about the dual GST model (0.875), applicable tax rates (0.639), and requirements of newly established e-way bills (0.713) led to the progression of the performance of the firms. Procedural knowledge (0.695), that is, GST compliances for MSMEs; scope of taxable items, and exemption list for MSMEs are crucial for on-time and proper tax compliances as non-compliance may lead to heavy fines, penalties and hamper the performance of the firms. This signifies acceptance of the hypothesis, H1: Tax knowledge positively impacts MSMEs’ performance.

Technological transition in the tax system has positively enhanced the performance as stated in

Table 5, (β-value 0.678 t-statistics 8.652;

p-value: (0.000). It demonstrates that the technology transition by the government with the implementation of the Goods and Service Tax Network (GSTN) has led to better tax governance (0.863), online tax jurisdiction (0.679) and tax administration (0.832) of the MSMEs. In addition, the technological shift led to paperless compliances (0.688) and saved much time (0.675) for MSMEs. The higher outer loading values (

Table 2) support that technology has positively enhanced performance. This signifies acceptance of the hypothesis,

H3: Technology transition for tax system positively impacts MSMEs’ business performance.

The study’s overall findings highlight a positive impact of tax knowledge and technology on performance. Tax information sources and firms’ characteristics positively influence GST awareness level in MSMEs, leading to the smooth adaption of technological change and enriching their tax knowledge to manage tax-related affairs. Proper tax knowledge and technological transition in the tax system have led to the prevention of frauds (0.898), high operational efficiency (0.856), and reduction in working capital blockage (0.836). The magnitude of R

2 and adjusted R

2 values (

Table 5) states that the PLS-SEM model can predict the impact significantly. Stone-Geisser’s Q

2 value [

106] for cross-validated predictive accuracy for the PLS path model is applied via a blindfolding procedure. The technique necessitates the omission of distance D. The recommended range of D is between 5 and 12 [

101]. For the present study, blindfolding results exhibit that the Q

2 value for performance is 0.454 (1-SSE/SSO).

6. Discussion and Conclusions

The effect of tax knowledge on micro, small and medium enterprises concerning their business performance is under-studied research, especially after the tax reform. Through this paper, we have tried to study the impact of tax knowledge and the technological framework after the tax reform (GST) on the performance level of Indian MSMEs. Partial Least Square Structured Equation Modeling is applied to develop a framework to know the impact on performance level. The study conducted a primary survey on 450 MSMEs in the northern region of India.

Worldwide, tax regulators, authorities, and policymakers realized that tax knowledge has led to better tax compliance by the taxpayers. Small informal businesses, especially in rural areas, are becoming more tax compliant with proper tax knowledge, which has benefited the governments and their businesses (OECD 2015). The present results emphasized the similar implications that after tax reform (GST), the proper tax knowledge (legal and procedural) about GST models, the exemption lists, and applicable tax rates has enabled smooth business flow. Moreover, tax knowledge prevented the firms from tax frauds and scams. In addition, it enhances the businesses’ efficiencies by enabling them to avail of timely tax benefits and not avoid taxes [

107,

108,

109].

The OECD (2015) report also emphasized that developing countries are adopting the new technological tax filing system, for which proper training, skill, and expert knowledge are required. The present research findings emphasized the technological aspect of GST; that is, the Goods and Service Tax Network has provided a single tax platform to taxpayers for all the matters related to the indirect tax system. It brought transparency to the system and led to better tax administration and governance. In addition, the robust I.T. system has saved MSMEs’ time by simplifying the cumbersome paperwork processes, which helped improve operational efficiencies. As supported by the study of Suparadianto, Ferdiana, and Sulistyo [

110], technology plays an essential part in setting up any new tax reform and easing the working procedures of the business.

Moreover, the studies by Alakam [

111], the income tax department [

112], and Sharp [

113] highlighted that many developing countries such as India, South Africa, and Nigeria opt to spread tax awareness through televisions during the tax filing due date periods of the year. Similar implications are observed in the present study that information sources such as tax journals, books, newspapers, internet at the national level amplify tax awareness among taxpayers. Further, the knowledge shared by tax experts [

88] helps businesses sustain in the complex tax environment so that new taxation policies may not prove a hurdle to their business performance.

Further, in the past, a strong association was observed between firms’ characteristics and tax evasion [

114] and tax avoidance [

115] and firms’ performance [

116]. On the other hand, firms’ characteristics in regards to tax awareness level are still under-researched, which is being highlighted through present empirical findings. According to GST Act 2017, different tax slab rates, procedures, and rules prevail for MSMEs based on their nature of business (manufacturing and servicing) and the type of goods and services. The government has liberalized special norms for these firms—a threshold limit of INR four million to get registered if the MSMEs deal in goods and a threshold of INR two million if in services. A particular composition scheme is also allowed if the MSME deals in goods and services, such as the cumulative tax preferential rate [

99,

117]. If the MSMEs are unaware of the unique benefits and tax rates applicable to them according to their nature of business, it might hamper their performance—operational and profit margins. The study highlights that firms’ characteristics are crucial in tax awareness and knowledge, as they help define their benefits.

7. Practical Implications

The major implications are for governments, policymakers, and MSMEs’ businesses. Policymakers and governments should spread more awareness regarding the new taxation reform implemented in the country through seminars and workshops to eradicate the ambiguity regarding changing tax laws and regulations. It would lead to timely tax compliance, generation of revenue, increased business efficiency, and reduction in tax scams.

The findings may prove beneficial to MSMEs as they are resource constraints and low on administrative sources. With proper tax awareness and knowledge through tax seminars, workshops, and available tax agent services, they can become more vigilant about the special tax incentives and schemes applicable to their respective businesses. Further, in-depth tax knowledge and awareness can help them in tax planning by keeping their business strategies that can enhance their efficiency. The information sources (tax journals, newspapers, internet) may provide the MSMEs the related tax information with ease and on time, saving them from tax fines and penalties and improving their operative performance. Furthermore, MSMEs form the backbone for industrial development in rural areas and must be aided with proper technical skills for the new I.T. structure implemented in the GST regime. It would boost the small firm to establish a solid foot in the international market without difficulty.

From a theoretical standpoint, our work adds to the literature in the Indian MSMEs context. The association of firms’ characteristics with awareness level apart from performance level is a new insight. If MSMEs are aware of the precise tax rules, regulations, tax agent services, and special training sessions being provided to them as per their firms’ size, legal stature, and nature of business, it will boost their productivity and reduce the blockage of funds. Furthermore, tax knowledge enhances business transparency, which may lead to sustainable economic development. Tax awareness and knowledge have always been powerful government tools to drive tax behavior. Firms with in-depth tax knowledge and awareness are more tax compliant and attract fewer tax fines and penalties. This tax-compliant behavior leads to financial sustainability, that is, a better business performance which is one of the key sustainable development goals. Moreover, tax knowledge helps narrow down the negative perception and enables the business to follow the rules and regulations easily and without delay, which not only enhances tax compliance but also saves their productive time as they are aware of the applicable tax laws.

Further, businesses can be motivated to make more environmentally informed decisions about operations and consumption by using the tax system and its incentives to reflect actual environmental costs and benefits without tax evasion or avoidance. Taxes and incentives will be a part of the network of policies that leads to more environmentally informed choices, and these choices will lead to a better world.

In terms of limitations, the present study focused on the data from one of the northern states of India. Thus, future research can be based on all the country’s regions (south, west, and east) to provide a broader perspective of all types of MSMEs. This will enable the government and businesses to identify the shortcomings and the immediate impact on their business performance. Further, future research might use different methodologies, and the impact of debt level along with a firm’s characteristics can be influential research in regards to tax policy change.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.B, R.K.S.; I.K; methodology, N.B; R.K.S.; software, N.B.; validation, R.K.S. and I.K.; formal analysis, N.B.; investigation, N.B.; resources, N.B.; data curation, N.B.; writing—original draft preparation, N.B.; writing—review and editing, R.K.S. and I.K.; supervision, R.K.S. and I.K.; funding acquisition, N.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The complete dataset of the responses that support the findings of this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We thank Chartered Accountant Suresh Kumar Bhalla for his expert guidance. He is a certified tax practitioner, practicing for more than 40 years, and his specialization has helped a lot in research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Boot-strap model.

Figure A1.

Boot-strap model.

References

- Susyanti, J.; Askandar, N.S. Why is tax knowledge and tax understanding important. JEMA J. Ilm. Bid. Akunt. Dan Manaj. 2016, 16, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agustiningsih, W.; Isroah, I. The effect of e-filing implementation, taxpayer awareness level and taxpayer on taxpayer compliance. J. Numinal 2016, 2, 107–122. [Google Scholar]

- Compliance Risk Management: Managing and Improving Tax Compliance; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Report 2004; Centre for Tax Policy and Administration: Paris, France, 2004.

- Inasius, F. Factors influencing SME tax compliance: Evidence from Indonesia. Int. J. Public Adm. 2019, 42, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Trade Organisation Report 2019. Available online: https://www.wto.org (accessed on 19 June 2020).

- Aruna. Impact of Goods and Service Tax on Indian Economy. Eur. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2019, 7, 106–112.

- Barbone, L.; Bird, R.M.; Caro, J.V. The Costs of VAT: A Review of the Literature; CASE Network Report No. 106; Center for Social and Economic Research (CASE): Warsaw, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pashev, K.V. Countering cross-border VAT fraud: The Bulgarian experience. J. Financ. Crime 2007, 14, 490–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilks, D.C.; Cruz, J.; Sousa, P. Please give me an invoice: VAT evasion and the Portuguese tax lottery. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2019, 39, 412–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loo, E.C.; Evans, C.; McKerchar, M.A. Challenges in understanding compliance behaviour of taxpayers in Malaysia. Asian J. Bus. Account. 2012, 3, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loo, E.C. The Influence of the Introduction on Self-Assessment on Compliance Behaviour of Individual Taxpayers in Malaysia. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Loo, E.C.; McKerchar, M.; Hansford, A. Understanding the compliance behaviour of Malaysian individual taxpayers using a mixed method approach. J. Australas. Tax Teach. Assoc. 2014, 4, 181–202. [Google Scholar]

- Arewa, M.; Davenport, S. The Tax and Technology Challenge. Innovations in Tax Compliance: Building Trust, Navigating Politics, and Tailoring Reform; Bill and Milenda Gates Foundations: Seattle, WA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Le, H.T.D.; Bui, M.T.; Nguyen, G.T.C. Factors affecting electronic tax compliance of small and medium enterprises in Vietnam. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2021, 8, 823–832. [Google Scholar]

- OECD Report 2015a. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/tax/forum-on-tax-administration/publications-and-products/supporting-smes-to-get-tax-right-strategic-planning.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2020).

- Kamleitner, B.; Korunka, C.; Kirchler, E. Tax compliance of small business owners. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2012, 18, 330–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fjeldstad, O.H.; Heggstad, K. Building taxpayer culture in Mozambique, Tanzania and Zambia: Achievements, challenges and policy recommendations. CMI Rep. 2012. Available online: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.259.6369&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Braithwaite, V.; Reinhart, M.; Smart, M. Tax non-compliance among the under-30s: Knowledge, obligation or scepticism. In Developing Alternative Frameworks for Explaining Tax Compliance; Routledge Taylor and Francis Group: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development. 2009. Available online: https://www.oecd.org (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Bornman, M.; Ramutumbu, P. A conceptual framework of tax knowledge. Meditari Account. Res. 2019, 27, 823–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garmia Pande and Rahul Patni. Tax Technology and Transformation. 2019. Available online: https://assets.ey.com/content/dam/ey-sites/ey-com/en_gl/topics/digital/ey-tax-technology-transformation.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- International Monetary Fund Report. 2020. Available online: https://www.imf.org (accessed on 18 December 2020).

- Bartole, T. The structure of embodiment and the overcoming of dualism: An analysis of Margaret Lock’s paradigm of embodiment. Dialect. Anthropol. 2012, 36, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swann, J. How science can contribute to the improvement of educational practice. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 2003, 29, 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmayanti, N.P.; Prihatiningtias, Y.W. Effect of tax penalties, tax audit, and taxpayers awareness on corporate taxpayers’ compliance moderated by compliance intentions. Int. J. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2020, 9, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einhorn, H.J.; Hogarth, R.M. Behavioral decision theory: Processes of judgement and choice. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1981, 32, 53–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libby, R.; Luft, J. Determinants of judgment performance in accounting settings: Ability, knowledge, motivation, and environment. Account. Organ. Soc. 1993, 18, 425–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallaha, A.M.; Shukor, Z.A.; Hassan, N. Factors influencing e filing usage among Malaysian taxpayers: Does tax knowledge matter? J. Pengur. 2014, 40, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauziati, P.; Minovia, A.F.; Muslim, R.Y.; Nasrah, R. The impact of tax knowledge on tax compliance case study in Kota Padang, Indonesia. J. Adv. Res. Bus. Manag. Stud. 2020, 2, 22–30. [Google Scholar]

- Baru, A. The impact of tax knowledge on tax compliance. J. Adv. Res. Bus. Manag. Stud. 2016, 6, 22–30. [Google Scholar]

- Kanda, R.; Handa, H.; Kumar, V.; Bhalla, G.S. Impact of GST on the Working of Rural India—A Study Assessing the Impacts of the New Taxation System on Business Sector in Lower Himachal Pradesh. TSM Bus. Rev. Int. J. Manag. 2018, 6, 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Mohan, V.; Ali, S. Assessment of the implication of GST (Goods and Service Tax) rollout on Indian MSME. Theor. Econ. Lett. 2018, 8, 3567–3580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Empson, L. Fear of exploitation and fear of contamination: Impediments to knowledge transfer in mergers between professional service firms. Hum. Relat. 2001, 54, 839–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, T.; Empson, L. Organisation and expertise: An exploration of knowledge bases and the management of accounting and consulting firms. Account. Organ. Soc. 1998, 23, 609–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, D.J.; Robson, K. Accounting, professions and regulation: Locating the sites of professionalization. Account. Organ. Soc. 2006, 31, 415–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbins, M.; Jamal, K. Problem-centred research and knowledge-based theory in the professional accounting setting. Account. Organ. Soc. 1993, 18, 451–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, S. Small Business Owners’ Perception on Value Added Tax Administration in Ghana: A Preliminary Study. Account. Tax. 2020, 12, 97–105. [Google Scholar]

- Faizal, S.M.; Palil, M.R.; Maelah, R.; Ramli, R. The Mediating Effect of Power and Trust in the Relationship Between Procedural Justice and Tax Compliance. Asian J. Account. Gov. 2019, 11, 52–66. [Google Scholar]

- Adam, C.; Webly, P. Small business owner’s attitude on vat compliance in the U.K. J. Econ. Psychol. 2012, 22, 195–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berhane, Z. The Influence of Tax Education on Tax Compliance Attitude; Addis Ababa University: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2011; pp. 1–170. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, M.; Zalilawati, Y.; Amran, M.; Choong, K. Quest for tax education in non-accounting curriculum: A Malaysian study. Asian Soc. Sci. 2013, 9, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansui, S.; Omar, N.; Sansui, Z.M. Good and Services Tax (GST) in Malaysian new tax environment. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 31, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, M.G. Tax Reform in India: Achievements and challenges. Asia Pac. Dev. J. 2006, 7, 59–74. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, R.K.; Mukherjee, S.; Bagchi, A. Goods and Services Tax in India; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Oktaviani, A.A.; Juang, F.T.; Kusumaningtyas, D.A. The Effect of Knowledge and Understanding Taxation, Quality of Tax Services, and Tax Awareness on Personal Tax Compliance. Indones. Manag. Account. Res. 2019, 16, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muliari, N.K.; dan Setiawan, P.E. The effect of perceptions about tax sanctions and taxpayer awareness on taxpayer reporting compliance with personal persons at the tax service office Pratama Denpasar East. Sci. J. Account. Bus. 2011, 6, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, A. Rakyat Perlu Cuba Faham GST. Sinar Harian, 15 March 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Shamsuddin, A.; Ruslan, M.M.; Halim, A.A.; Zahari, N.F.; Fazi, N.M. Educators’ awareness and acceptance towards Goods and Services Tax (GST) implementation in Malaysia: A study in Bandar Muadzam Shah, Pahang. Int. J. Bus. Econ. Law 2014, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Urif, H.B. Employees’ Attitudes towards Goods and Services Tax (GST) in Open University Malaysia. Imp. J. Interdiscip. Res. 2016, 2, 92–99. [Google Scholar]

- Choong, K.F.; Lai, M.L. Towards goods and services tax in Malaysia: A Preliminary Study. Glob. Bus. Econ. Anthol. 2006, 1, 75–86. [Google Scholar]

- Saira, K.; Zariyawati, M.; May, L.Y. An Exploratory Study of Goods and Services Tax Awareness in Malaysia. Political Manag. Policies Malays. 2010, S14, 265–276. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Kesan, J.P. Do tax policies drive innovation by SMEs in China? J. Small Bus. Manag. 2020, 60, 309–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lymer, A.; Hansford, A.; Pilkington, K. Developments in tax e-filing: Practical views from the coalface. J. Appl. Account. Res. 2012, 13, 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalaja, L. GST and ITS Implications on Indian Economy. J. Bus. Manag. 2017, 67–73. Available online: https://iosrjournals.org/iosr-jbm/papers/Conf.17037-2017/Volume-2/12.%2067-73.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Bird, R.M.; Zolt, E.M. Technology and Taxation in Developing Countries: From hand to mouse. Natl. Tax J. 2008, 61, 791–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohja, A.; Sahu, G.P.; Gupta, M.P. Antecedents of Paperless income tax filing by young professionals in India: An exploratory study. Transform. Gov. People Process Policy 2009, 3, 65–90. [Google Scholar]

- Soneka, P.N.; Phiri, J. A Model for Improving E-Tax Systems Adoption in Rural Zambia Based on the TAM Model. Open J. Bus. Manag. 2019, 7, 908–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakhmawati, H.; Rusydi, M.K. Influence of TAM and UTAUT models of the use of e-filing on tax compliance. Int. J. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2020, 9, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radian, A. Resource Mobilization in Poor Countries: Implementing Tax Policies; Transaction Publishers: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Eichfelder, S.; Schorn, M. Tax compliance costs: A business-administration perspective. FinanzArchiv Public Financ. Anal. 2012, 68, 191–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadri, R.A.; Darmawan, E. E-Filing Implementation, Tax Compliance, and Technology Authority. J. Appl. Account. Tax. 2021, 6, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, L.; Kaur, B. Tax Payer’s Perception towards Goods and Service Tax in India. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Management and Information Systems, Jakarta, Indonesia, 3–5 September 2018; pp. 21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, L.M.; Muhammad, I. Taxation and technology: Technology readiness of Malaysian tax officers in petaling jaya branch. J. Financ. Rep. Account. 2006, 4, 147–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, L.M.; Nawawi, N.H.A. Integrating ICT skills and tax software in tax education: A survey of Malaysian tax practitioners’ perspectives. Campus-Wide Inf. Syst. 2010, 27, 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, H.; Barua, M.K. Identifying enablers of technological innovation for Indian MSMEs using best–worst multi criteria decision making method. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2016, 107, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Night, S.; Bananuka, J. The mediating role of adoption of an electronic tax system in the relationship between attitude towards electronic tax system and tax compliance. J. Econ. Financ. Adm. Sci. 2019, 25, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpan, I.J.; Udoh, E.A.P.; Adebisi, B. Small business awareness and adoption of state-of-the-art technologies in emerging and developing markets, and lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 2020, 34, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asianzu, E.; Maiga, G. A Consumer Based Model for E-Tax Services Adoption in Uganda. In Proceedings of the 2012 Annual SRII Global Conference, San Jose, CA, USA, 24–27 July 2012; pp. 614–622. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, J.; Barzotto, M.; Khorasgani, A. Does size matter in predicting SMEs failure? Int. J. Financ. Econ. 2018, 23, 571–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, C.K.W.; Fung, M.K.Y. Firm size and performance of manufacturing enterprises in P.R. China: The case of Shanghai’s manufacturing industries. Small Bus. Econ. 1997, 9, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, F.; Lenzelbauer, W. An inverse relationship between efficiency and profitability according to size of (Upper-) Austrian firms? Some further tentative results. Small Bus. Econ. 1993, 5, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, F. Efficiency and profitability: An inverse relationship according to the size of Austrian firm? Small Bus. Econ. 1991, 3, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athari, S.A.; Bahreini, M. The impact of external governance and regulatory settings on the profitability of Islamic banks: Evidence from Arab markets. Int. J. Financ. Econ. 2021, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athari, S.A. Domestic political risk, global economic policy uncertainty, and banks’ profitability: Evidence from Ukrainian banks. Post-Communist Econ. 2021, 33, 458–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haryaningsih, S.; Abao, A.S. Strategi Pembentukan Sikap Wajib Pajak Dalam Mewujudkan Program Electronic Filing (E-Filing) Di Kota Pontianak Dengan Pemahaman Menuju Era Ekonomi Digital. Reformasi Adm. 2020, 7, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudiartana, I.M.; Mendra, N.P.Y. Faktor—Faktor Yang Mempengaruhi Kepatuhan Wajib Pajak. Proc. TEAM 2017, 2, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockfield, A.J. How countries should share tax information. Vand. J. Transnat’l L. 2017, 50, 1091–1110. [Google Scholar]

- Partap, S.A. The impact of GST and MSME sector. GST simplified tax system: Challenges and Remedies. Paradigm 2018, 1, 315–318. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.; Wang, T.; Zhan, Z. From business tax to value-added tax: The effects of reform on Chinese transport industry firms. Aust. Account. Rev. 2019, 29, 158–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sury, M.M. Goods and Services Tax (GST) in India: Background, Present Structure and Future Challenges: As Applicable from July 1, 2017; New Century Publications: Hong Kong, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Saad, N. Tax knowledge, tax complexity and tax compliance: Taxpayers’ view. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 109, 1069–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritsema, C.M.; Thomas, D.W.; Ferrier, D.G. Economic and behaviourist determinants of tax compliance. In Proceedings of the 2011 IRS Research conference, Washington, DC, USA, 22 June 2011; Ankasans Tax Penalty Amnesty Program: Holland, MI, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Shackelford, D.A.; Shevlin, T. Empirical tax research in accounting. J. Account. Econ. 2001, 31, 321–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Chen, X.; Cheng, Q.; Shevlin, T.J. Are family firms more tax aggressive than nonfamily firms? J. Financ. Econ. 2010, 95, 41–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, G.M.C.; Marques, C.S.; Ratten, V.; Ferreira, J.J. The impact of knowledge creation and acquisition on innovation, coopetition and international opportunity development. Eur. J. Int. Manag. 2021, 16, 450–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MSME Report 2020–2021. Available online: https://msme.gov.in/sites/default/files/MSME-ANNUAL-REPORT-ENGLISH%202020-21.pdf (accessed on 31 March 2021).

- Wassermann, M.; Bornman, M. Tax knowledge for the digital economy. J. Econ. Financ. Sci. 2020, 13, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, C.; Hansford, A.; Hasseldine, J.; Lignier, P.; Smulders, S.; Vaillancourt, F. Small business and tax compliance costs: A cross-country study of managerial benefits and tax concessions. Ejournal Tax Res. 2014, 12, 453–482. [Google Scholar]

- Lesage, D.; Lips, W.; Vermeiren, M. The BRICs and International Tax Governance: The case of automatic exchange of information. New Polit. Econ. 2020, 25, 715–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Internet and Mobile Association of India (IAMAI). Impact of GST on Online Marketplaces; Internet and Mobile Association of India: Mumbai, India, 2016; pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Vij, S.; Bedi, H.S. Are subjective business performance measures justified? Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2016, 65, 603–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, T.D.; Michie, J.; Patterson, M.; Wood, S.J.; Sheehan, M.; Clegg, C.H.; West, M. On the Validity of Subjective Measures of Company Performance. Pers. Psychol. 2004, 57, 95–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dess, G.G.; Robinson, R.B., Jr. Measuring organizational performance in the absence of objective measures: The case of the privately-held firm and conglomerate business unit. Strateg. Manag. J. 1984, 5, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masa’deh, R.; Tayeh, M.; Al-Jarrah, I.M.; Tarhini, A. Accounting vs. Market-based Measures of Firm Performance Related to Information Technology Investments. Int. Rev. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2015, 9, 129–145. [Google Scholar]

- Runyan, R.; Droge, C.; Swinney, J. Entrepreneurial orientation versus small business orientation: What are their relationships to firm performance? J. Small Bus. Manag. 2008, 46, 567–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haber, S.; Reichel, A. Identifying performance measures of small ventures—the case of the tourism industry. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2005, 43, 257–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoseini, M.; Briand, O. Production efficiency and self-enforcement value added tax: Evidence from state-level reform in India. J. Dev. Econ. 2020, 144, 102462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, R. The validity of ROI as a measure of business performance. Am. Econ. Rev. 1987, 77, 470–478. [Google Scholar]

- Central Goods and Services Tax Act. 2017. Available online: https://www.cbic.gov.in/htdocs-cbec/gst/gstacts (accessed on 31 March 2019).

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with Mplus: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming; Routledge Taylor and Francis Group: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F. Multivariate Data Analysis: An Overview. In International Encyclopedia of Statistical Science; Pearson Publications: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill Book Company: New York, NY, USA, 1978; Volume 86, pp. 190–255. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y.; Phillips, L.W. Assessing construct validity in organizational research. Adm. Sci. Q. 1991, 36, 421–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, M. Cross-Validatory Choice and Assessment of Statistical Predictions. J. R. Stat. Soc. 1974, 36, 111–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koubaa, R.R.; Jarboui, A. Normal, abnormal book-tax differences and accounting conservatism. Asian Acad. Manag. J. Account. Financ. 2017, 13, 25–39. [Google Scholar]

- Blaylock, B.; Shevlin, T.; Wilson, R.J. Tax avoidance, large positive temporary book-tax differences, and earnings persistence. Account. Rev. 2011, 87, 91–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanlon, M.; Laplante, S.K.; Shevlin, T.J. Evidence on the possible information loss of conforming book income and taxable income. J. Law Econ. 2005, 48, 407–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdiana, R.; Sulistyo, S. The Role of Information Technology Usage on Startup Financial Management and Taxation. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2019, 161, 1308–1315. [Google Scholar]

- Alakam, J. Nigeria: Firs’s New Drama Series Harps on Tax Compliance. August 2013. Available online: https://allafrica.com/stories/201308051996.htm (accessed on 4 August 2013).

- Sharp, L. SARS’ Threatening T.V. Ads Are Counter-Productive. 2015. Available online: http://www.acts.co.za/news/blog/2015/01/sars-threatening-tv-ads-are-counterproductive (accessed on 16 May 2019).

- Income Tax Department. Income Tax Department, Government of India: Publicity Campaigns. 2019. Available online: https://www.incometaxindia.gov.in/Pages/publicity-campaign.aspx (accessed on 31 March 2022).

- Rashid, M.H.U.; Morshed, A. Firms’ Characteristics and Tax Evasion. In Handbook of Research on Theory and Practice of Financial Crimes; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 428–451. [Google Scholar]

- Brune, A.; Thomsen, M.; Watrin, C. Tax avoidance in different firm types and the role of nonfamily involvement in private family firms. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2019, 40, 950–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhalla, N.; Kaur, I.; Sharma, R.K. Examining the Effect of Tax Reform Determinants, Firms’ Characteristics and Demographic Factors on the Financial Performance of Small and Micro Enterprises. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economics Times Report 2022. Available online: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/small-biz/gst/five-years-of-gst-is-it-a-gamechanger-for-msmes/articleshow/92587574.cms (accessed on 1 July 2022).

| Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).