The Effects of Job Crafting on Job Performance among Ideological and Political Education Teachers: The Mediating Role of Work Meaning and Work Engagement

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Development of Hypotheses

2.1. Job Crafting

2.2. Job Crafting and Job Performance

2.3. The Mediating Roles of Work Meaning and Work Engagement

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection and Participant Characteristics

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Job Crafting

3.2.2. Work Meaning

3.2.3. Work Engagement

3.2.4. Job Performance

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

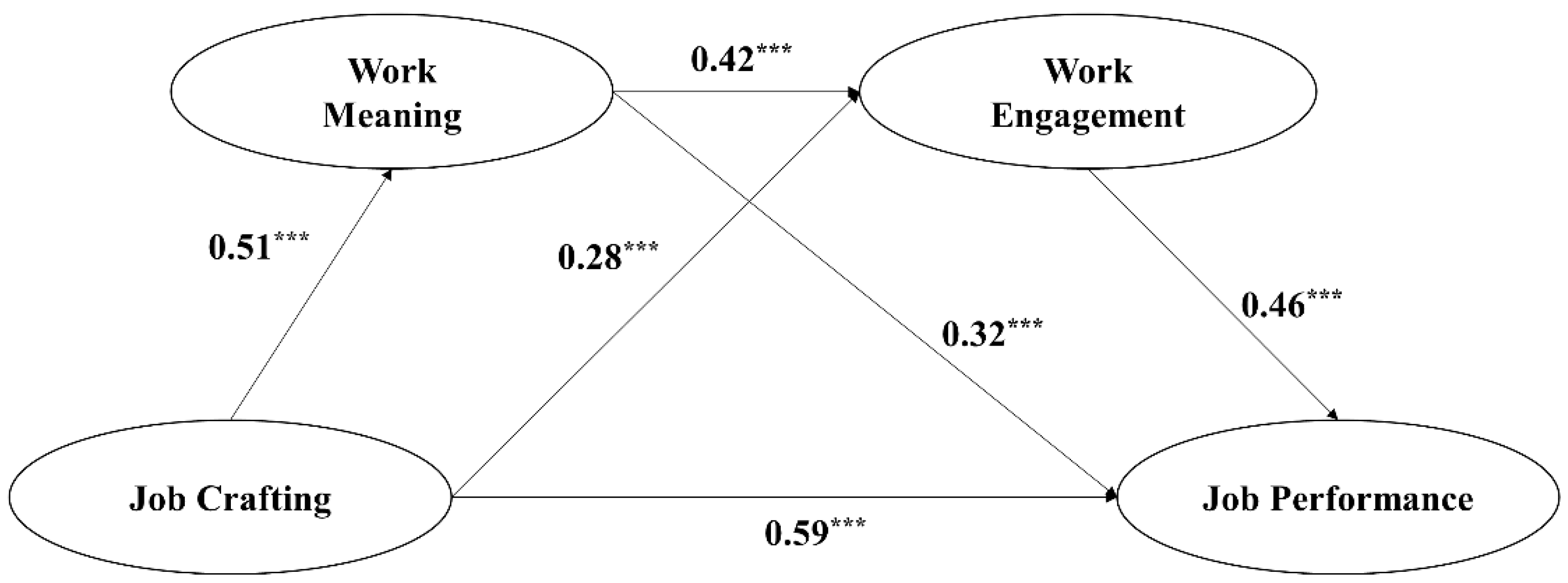

4.2. Structural Equation Modelling

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yong, J.Y.; Yusliza, M.Y.; Ramayah, T.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Sehnem, S.; Mani, V. Pathways towards sustainability in manufacturing organizations: Empirical evidence on the role of green human resource management. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2020, 29, 212–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Call, M.L.; Nyberg, A.J.; Thatcher, S.M.B. Stargazing: An Integrative Conceptual Review, Theoretical Reconciliation, and Extension for Star Employee Research. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 623–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latukha, M.; Zhang, Y.G.; Panibratov, A.; Arzhanykh, K.; Rysakova, L. Talent management practices for firms’ absorptive capacity in a host country: A study of the Chinese diaspora in Russia. Crit. Perspect. Int. Bus. 2022. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.P. The pains of educational transition: Contradictions and changes. J. Chin. Soc. Educ. 2014, 1, 23–27. [Google Scholar]

- Valli, L.; Buese, D. The changing roles of teachers in an era of high-stakes accountability. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2007, 44, 519–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tian, J. An ecological examination of teachers’ development in the context of transformation of local universities. High. Educ. Explor. 2019, 01, 124–128. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, X.; Sun, C.; Sun, B.; Yuan, X.; Ding, F.; Zhang, M. The Cost of Caring: Compassion Fatigue Is a Special Form of Teacher Burnout. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dam, K.; Oreg, S.; Schyns, B. Daily work contexts and resistance to organisational change: The role of leader-member exchange, development climate, and change process characteristics. Appl. Psychol-Int. Rev. 2008, 57, 313–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The Job Demands-Resources model: State of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Toyama, H.; Upadyaya, K.; Salmela-Aro, K. Job crafting and well-being among school principals: The role of basic psychological need satisfaction and frustration. Eur. Manag. J. 2021, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzesniewski, A.; Dutton, J.E. Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jutengren, G.; Jaldestad, E.; Dellve, L.; Eriksson, A. The Potential Importance of Social Capital and Job Crafting for Work Engagement and Job Satisfaction among Health-Care Employees. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzesniewski, A.; Lobuglio, N.; Dutton, J.E.; Berg, J.M. Job Crafting and Cultivating Positive Meaning and Identity in Work; Advances in Positive Organizational Psychology; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, J.M.; Dutton, J.E.; Wrzesniewski, A. Job Crafting and Meaningful Work. In Purpose and Meaning in the Workplace; Dik, B.J., Byrne, Z.S., Steger, M.F., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; pp. 81–104. [Google Scholar]

- May, D.R.; Gilson, R.L.; Harter, L.M. The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and the engagement of the human spirit at work. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2004, 77, 11–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.Y.; Guo, C. Job crafting: The new path for meaningful work and personal growth. J. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 37, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Letona, O.; Solano, A.A.; Martínez-Rodriguez, S.; Carrasco, M.; Marqués, N. Job crafting and work engagement: The mediating role of work meaning. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M.; Ashford, S.J. The dynamics of proactivity at work. Res. Organ. Behav. 2008, 28, 3–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulik, C.T.; Oldham, G.R.; Hackman, J.R. Work design as an approach to person-Environment fit. J. Vocat. Behav. 1987, 31, 278–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slemp, G.R.; Vella-Brodrick, D.A. Optimising employee mental health: The relationship between intrinsic need satisfaction, job crafting, and employee well-being. J. Happiness Stud. 2014, 15, 957–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Derks, D. Development and validation of the job crafting scale. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B. Job crafting: Towards a new model of individual job redesign. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2010, 36, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.P.; Mccloy, R.A.; Oppler, S.H.; Sager, C.E. A Theory of Performance. In Personnel Selection in Organizations; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, S.S.K.; Chen, X.P.; Schaubroeck, J. Participative decision making and employee performance in different cultures: The moderating effects of allocentrism/idiocentrism and efficacy. Acad. Manag. J. 2002, 45, 905–914. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, L.J.; Anderson, S.E. Job-satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behaviors. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 601–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, H.J.; Demerouti, E.; Le Blanc, P.M.; Bipp, T. Job crafting and performance of Dutch and American health care professionals. J. Pers. Psychol. 2015, 14, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, P. The crafting of jobs and individual differences. J. Bus. Psychol. 2008, 23, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, P.C.; Fan, M.J.; Liu, S.Y. Influence of job crafting on adaptive performance from the perspective of information processing theory. J. Cap. Univ. Econ. Bus. 2022, 24, 101–112. [Google Scholar]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Derks, D. The impact of job crafting on job demands, job resources, and well-being. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2013, 18, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rudolph, C.W.; Katz, I.M.; Lavigne, K.N.; Zacher, H. Job crafting: A meta-analysis of relationships with individual differences, job characteristics, and work outcomes. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 102, 112–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosso, B.D.; Dekas, K.H.; Wrzesniewski, A. On the meaning of work: A theoretical integration and review. Res. Organ. Behav. 2010, 30, 91–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M.F.; Dik, B.J.; Duffy, R.D. Measuring meaningful work: The work and meaning inventory (WAMI). J. Career Assess. 2012, 20, 322–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wrzesniewski, A.; Berg, J.M.; Dutton, J.E. Managing yourself: Turn the job you have into the job you want. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2010, 88, 114–117. [Google Scholar]

- Tims, M.; Derks, D.; Bakker, A.B. Job crafting and its relationships with person-job fit and meaningfulness: A three-wave study. J. Vocat. Behav. 2016, 92, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrou, P.; Bakker, A.B.; van den Heuvel, M. Weekly job crafting and leisure crafting: Implications for meaning-making and work engagement. J. Occup. Organ. Psych. 2017, 90, 129–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermooten, N.; Boonzaier, B.; Kidd, M. Job crafting, proactive personality and meaningful work: Implications for employee engagement and turnover intention. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2019, 45, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 25, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Salanova, M.; González-Romá, V.; Bakker, A.B. The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. J. Happiness Stud. 2002, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Towards a model of work engagement. Career Dev. Int. 2008, 13, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nielsen, K.; Abildgaard, J.S. The development and validation of a job crafting measure for use with blue-collar workers. Work Stress 2012, 26, 365–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Derks, D.; Rhenen, W.V. Job crafting at the team and individual Level: Implications for work engagement and performance. Group Organ. Manag. 2013, 38, 427–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.X.; Du, H.F.; Xie, B.G.; Mo, L. Work engagement and job performance: The moderating role of perceived organizational support. An. Psicol. 2017, 33, 708–713. [Google Scholar]

- Oprea, B.T.; Barzin, L.; Virga, D.; Iliescu, D.; Rusu, A. Effectiveness of job crafting interventions: A meta-analysis and utility analysis. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2019, 28, 723–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geldenhuys, M.; Laba, K.; Venter, C.M. Meaningful work, work engagement and organisational commitment. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2014, 40, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzesniewski, A.; McCauley, C.; Rozin, P.; Schwartz, B. Jobs, careers, and callings: People’s relations to their work. J. Res. Personal. 1997, 31, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zyl, L.V.; Deacon, E.; Rothmann, S. Towards happiness: Experiences of work-role fit, meaningfulness and work engagement of industrial/organisational psychologists in South Africa. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2010, 36, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Makikangas, A. Job crafting profiles and work engagement: A person-centered approach. J. Vocat. Behav. 2018, 106, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. The Impact of Career Aspiration on Job Crafting; Zhejiang University Press: Hangzhou, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy, R.D.; Autin, K.L.; Bott, E.M. Work Volition and Job Satisfaction: Examining the Role of Work Meaning and Person–Environment Fit. Career Dev. Q. 2015, 63, 126–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.W.; Gan, Y.Q. The Chinese Version of Utrecht Work Engagement Scale: An Examination of Reliability and Validity. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 13, 268–270. [Google Scholar]

- Mastenbroek, N.J.J.M.; Jaarsma, A.D.C.; Scherpbier, A.J.J.A.; Van Beukelen, P.; Demerouti, E. The role of personal resources in explaining well-being and performance: A study among young veterinary professionals. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2014, 23, 190–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, S.A.; Svyantek, D.J. Person-Organization Fit and Contextual Performance: Do Shared Values Matter. J. Vocat. Behav. 1999, 55, 254–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dan, C.I.; Roca, A.C.; Mateizer, A. Job Crafting and Performance in Firefighters: The Role of Work Meaning and Work Engagement. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavy, S.; Ayuob, W. Teachers’ Sense of Meaning Associations with Teacher Performance and Graduates’ Resilience: A Study of Schools Serving Students of Low Socio-Economic Status. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakanen, J.J.; Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. How dentists cope with their job demands and stay engaged: The moderating role of job resources. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2005, 113, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seppl, P.; Harju, L.K.; Hakanen, J.J. Interactions of Approach and Avoidance Job Crafting and Work Engagement: A Comparison between Employees Affected and Not Affected by Organizational Changes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harju, L.K.; Hakanen, J.J.; Schaufeli, W.B. Can job crafting reduce job boredom and increase work engagement? A three-year cross-lagged panel study. J. Vocat. Behav. 2016, 95–96, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakanen, J.J.; Peeters, M.C.; Schaufeli, W.B. Different Types of Employee Well-Being Across Time and Their Relationships with Job Crafting. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2018, 23, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britt, T.W.; Dickinson, J.M.; Greene-Shortridge, T.M.; Mckibben, E.S. Positive Organizational Behavior; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, H.S.; Yoon, H.H. What does work meaning to hospitality employees? The effects of meaningful work on employees’ organizational commitment: The mediating role of job engagement. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 53, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q. Research on job crafting from the perspective of sustainable career: Motivation, paths and intervention mechanisms. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2022, 30, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.Y.; Luo, Z.L.; Dong, Y. The work of future teachers: Innovation, cross-border collaboration and job crafting. Open Educ. Res. 2022, 28, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

| Measures | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Job crafting | 3.25 | 0.569 | 1.000 | |||

| 2. Work meaning | 3.04 | 0.521 | 0.512 ** | 1.000 | ||

| 3. Work engagement | 3.69 | 0.675 | 0.578 ** | 0.309 ** | 1.000 | |

| 4. Job performance | 3.56 | 0.572 | 0.53 1 ** | 0.415 ** | 0.602 ** | 1.000 |

| Model Pathways | Effect | 95% Confidence Interval | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | |||

| JC→JP | 0.59 *** | 0.536 | 0.591 | - |

| JC→WM | 0.51 *** | 0.521 | 0.586 | - |

| WM→JP | 0.32 *** | 0.375 | 0.408 | - |

| WM→WE | 0.42 *** | 0.431 | 0.487 | - |

| JC→WE | 0.28 *** | 0.326 | 0.419 | - |

| WE→JP | 0.46 *** | 0.452 | 0.493 | - |

| JC→WM→JP | 0.163 *** | 0.201 | 0.273 | 21.6% |

| JC→WE→JP | 0.129 *** | 0.169 | 0.216 | 17.9% |

| JC→WM→WE→JP | 0.099 *** | 0.042 | 0.093 | 14.3% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shang, W. The Effects of Job Crafting on Job Performance among Ideological and Political Education Teachers: The Mediating Role of Work Meaning and Work Engagement. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8820. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148820

Shang W. The Effects of Job Crafting on Job Performance among Ideological and Political Education Teachers: The Mediating Role of Work Meaning and Work Engagement. Sustainability. 2022; 14(14):8820. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148820

Chicago/Turabian StyleShang, Weiwei. 2022. "The Effects of Job Crafting on Job Performance among Ideological and Political Education Teachers: The Mediating Role of Work Meaning and Work Engagement" Sustainability 14, no. 14: 8820. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148820

APA StyleShang, W. (2022). The Effects of Job Crafting on Job Performance among Ideological and Political Education Teachers: The Mediating Role of Work Meaning and Work Engagement. Sustainability, 14(14), 8820. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148820