Local Wisdom for Ensuring Agriculture Sustainability: A Case from Indonesia

Abstract

1. Introduction

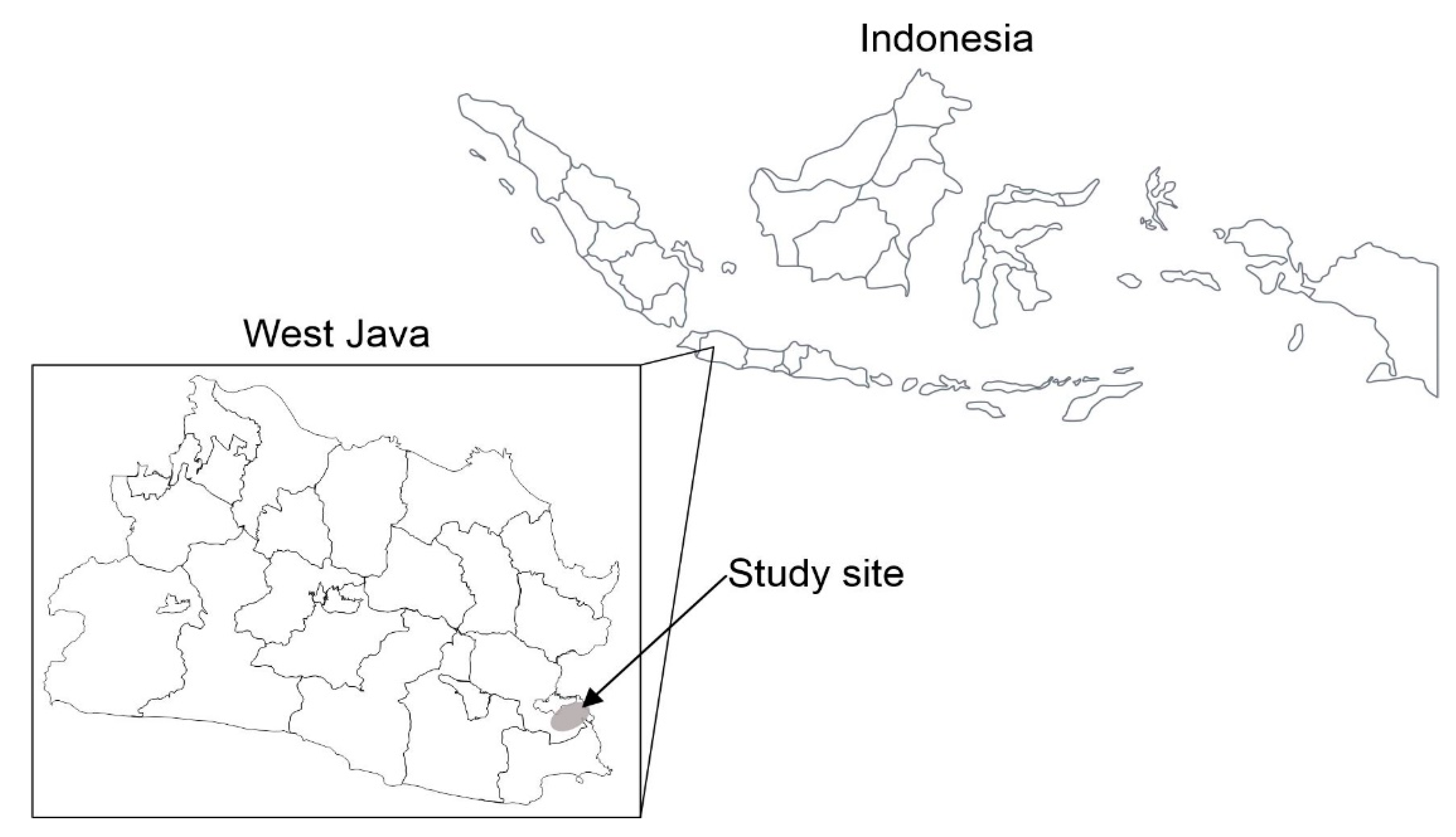

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Land Fragmentation: A Broader Situation

3.2. Land Fragmentation in Ciamis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Interview No. | Name | Date of Interview | Type of Data Collection | Type of Informants | Gender |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | TN | 12 January 2018 | FGD | Elder | m |

| 17 February 2018 | In-depth Interview | ||||

| 13 March 2018 | In-depth Interview | ||||

| 2 | DR | 12 January 2018 | FGD | Elder | m |

| 18 February 2018 | In-depth Interview | ||||

| 14 March 2018 | In-depth Interview | ||||

| 3 | NM | 12 January 2018 | FGD | Elder | m |

| 19 February 2018 | In-depth Interview | ||||

| 15 March 2018 | In-depth Interview | ||||

| 4 | PK | 12 January 2018 | FGD | Farmers Group Leader | m |

| 24 February 2018 | In-depth Interview | ||||

| 16 March 2018 | In-depth Interview | ||||

| 5 | MS | 12 January 2018 | FGD | Female Elder | f |

| 24 February 2018 | In-depth Interview | ||||

| 17 March 2018 | In-depth Interview | ||||

| 6 | SJ | 12 January 2018 | FGD | Female Elder | f |

| 25 February 2018 | In-depth Interview | ||||

| 18 March 2018 | In-depth Interview | ||||

| 7 | MM | 12 January 2018 | FGD | Female Elder | f |

| 25 February 2018 | In-depth Interview | ||||

| 19 March 2018 | In-depth Interview | ||||

| 8 | FS | 12 January 2018 | FGD | Successor | m |

| 26 February 2018 | In-depth Interview | ||||

| 2 April 2018 | In-depth Interview | ||||

| 9 | RSN | 12 January 2018 | FGD | Successor | m |

| 26 February 2018 | In-depth Interview | ||||

| 2 April 2018 | In-depth Interview | ||||

| 10 | NK | 12 January 2018 | FGD | Successor | f |

| 26 February 2018 | In-depth Interview | ||||

| 2 April 2018 | In-depth Interview | ||||

| 11 | NLK | 12 January 2018 | FGD | Successor | f |

| 27 February 2018 | In-depth Interview | ||||

| 3 April 2018 | In-depth Interview | ||||

| 12 | SM | 12 January 2018 | FGD | Successor | f |

| 27 February 2018 | In-depth Interview | ||||

| N/A | N/A | ||||

| 13 | RSA | 12 January 2018 | FGD | Successor | f |

| 27 February 2018 | In-depth Interview | ||||

| 3 April 2018 | In-depth Interview | ||||

| 14 | RK | 12 January 2018 | FGD | Successor | f |

| 28 February 2018 | In-depth Interview | ||||

| 3 April 2018 | In-depth Interview | ||||

| 15 | SDA | 12 January 2018 | FGD | Successor | f |

| 28 February 2018 | In-depth Interview | ||||

| 4 April 2018 | In-depth Interview | ||||

| 16 | YR | 12 January 2018 | FGD | Successor | f |

| 28 February 2018 | In-depth Interview | ||||

| 4 April 2018 | In-depth Interview | ||||

| 17 | FR | 12 January 2018 | FGD | Extension Agent | f |

| 1 March 2018 | In-depth Interview | ||||

| 5 April 2018 | In-depth Interview | ||||

| 18 | DH | 12 January 2018 | FGD | Extension Agent | m |

| 1 March 2018 | In-depth Interview | ||||

| 5 April 2018 | In-depth Interview | ||||

| 19 | DN | 12 January 2018 | FGD | Extension Agent | m |

| 2 March 2018 | In-depth Interview | ||||

| 6 April 2018 | In-depth Interview | ||||

| 20 | EK | 12 January 2018 | FGD | Extension Agent | m |

| 2 March 2018 | In-depth Interview | ||||

| 6 April 2018 | In-depth Interview | ||||

| 21 | IS | 12 January 2018 | FGD | Local Government | m |

| 3 March 2018 | In-depth Interview | ||||

| 7 April 2018 | In-depth Interview | ||||

| 22 | SJ | 12 January 2018 | FGD | Local Government | m |

| 3 March 2018 | In-depth Interview | ||||

| 7 April 2018 | In-depth Interview | ||||

| 23 | AS | 12 January 2018 | FGD | Local Government | m |

| 3 March 2018 | In-depth Interview | ||||

| 7 April 2018 | In-depth Interview |

References

- Rockström, J.; Steffen, W.L.; Noone, K.; Persson, A.; Chapin, F.S., III; Lambin, E.; Lenton, T.M.; Scheffer, M.; Folke, C.; Schellnhuber, H.J. Planetary boundaries: Exploring the safe operating space for humanity. Ecol. Soc. 2009, 14, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreda, T. Contesting conventional wisdom on the links between land tenure security and land degradation: Evidence from Ethiopia. Land Use Policy 2018, 77, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Dang, H. Addressing the dual challenges of food security and environmental sustainability during rural livelihood transitions in China. Land Use Policy 2018, 77, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Heerink, N.; Qu, F. Land fragmentation and its driving forces in China. Land Use Policy 2006, 23, 272–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Looga, J.; Jürgenson, E.; Sikk, K.; Matveev, E.; Maasikamäe, S. Land fragmentation and other determinants of agricultural farm productivity: The case of Estonia. Land Use Policy 2018, 79, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yucer, A.A.; Kan, M.; Demirtas, M.; Kalanlar, S. The importance of creating new inheritance policies and laws that reduce agricultural land fragmentation and its negative impacts in Turkey. Land Use Policy 2016, 56, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartvigsen, M. Land consolidation and land banking in Denmark-tradition, multi-purpose and perspectives. Dan. J. Geoinformatics Land Manag. 2014, 122, 51–74. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, J. Attempt on systematization of land consolidation approaches in Europe. Z. Für Vermess. 2006, 3, 156–161. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk, T. Scenarios of Central European land fragmentation. Land Use Policy 2003, 20, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijk, T. Complications for traditional land consolidation in Central Europe. Geoforum 2007, 38, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gónzalez, X.P.; Marey, M.F.; Álvarez, C.J. Evaluation of productive rural land patterns with joint regard to the size, shape and dispersion of plots. Agric. Syst. 2007, 92, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, X.P.; Alvarez, C.J.; Crecente, R. Evaluation of land distributions with joint regard to plot size and shape. Agric. Syst. 2004, 82, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prugh, L.R.; Hodges, K.E.; Sinclair, A.R.E.; Brashares, J.S. Effect of habitat area and isolation on fragmented animal populations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 20770–20775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janus, J.; Glowacka, A.; Bozek, P. Identification of areas with unfavorable agriculture development conditions in terms of shape and size of parcels with example of Southern Poland. Eng. Rural Dev. 2016, 25, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Alfiky, A.; Kaule, G.; Salheen, M. Agricultural Fragmentation of the Nile Delta; A Modeling Approach to Measuring Agricultural Land Deterioration in Egyptian Nile Delta. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2012, 14, 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latruffe, L.; Piet, L. Does land fragmentation affect farm performance? A case study from Brittany, France. Agric. Syst. 2014, 129, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, N.M.; Brudvig, L.A.; Clobert, J.; Davies, K.F.; Gonzalez, A.; Holt, R.D.; Lovejoy, T.E.; Sexton, J.O.; Austin, M.P.; Collins, C.D.; et al. Habitat fragmentation and its lasting impact on Earth’s ecosystems. Sci. Adv. 2015, 1, e1500052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rounsevell, M.D.A.; Pedroli, B.; Erb, K.-H.; Gramberger, M.; Busck, A.G.; Haberl, H.; Kristensen, S.; Kuemmerle, T.; Lavorel, S.; Lindner, M.; et al. Challenges for land system science. Land Use Policy 2012, 29, 899–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deininger, K.; Savastano, S.; Carletto, C. Land Fragmentation, Cropland Abandonment, and Land Market Operation in Albania; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Farley, K.A.; Ojeda-Revah, L.; Atkinson, E.E.; Eaton-González, B.R. Changes in land use, land tenure, and landscape fragmentation in the Tijuana River Watershed following reform of the ejido sector. Land Use Policy 2012, 29, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, K. The costs and benefits of land fragmentation of rice farms in Japan. Aust. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2010, 54, 509–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niroula, G.S.; Thapa, G.B. Impacts and causes of land fragmentation, and lessons learned from land consolidation in South Asia. Land Use Policy 2005, 22, 358–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.; Rahman, M. Impact of land fragmentation and resource ownership on productivity and efficiency: The case of rice producers in Bangladesh. Land Use Policy 2009, 26, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikor, T.; Müller, D.; Stahl, J. Land fragmentation and cropland abandonment in Albania: Implications for the roles of state and community in post-socialist land consolidation. World Dev. 2009, 37, 1411–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sklenicka, P.; Janovska, V.; Salek, M.; Vlasak, J.; Molnarova, K. The Farmland Rental Paradox: Extreme land ownership fragmentation as a new form of land degradation. Land Use Policy 2014, 38, 587–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrantes, P.; Fontes, I.; Gomes, E.; Rocha, J. Compliance of land cover changes with municipal land use planning: Evidence from the Lisbon metropolitan region (1990–2007). Land Use Policy 2016, 51, 120–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakari, Z.; van der Molen, P.; Bennett, R.M.; Kuusaana, E.D. Land consolidation, customary lands, and Ghana’s Northern Savannah Ecological Zone: An evaluation of the possibilities and pitfalls. Land Use Policy 2016, 54, 386–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartvigsen, M. Experiences with Land Consolidation and Land Banking in Central and Eastern Europe after 1989; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nation: Rome, Italy, 2015; Volume 26, pp. 8–16. [Google Scholar]

- Vitikainen, A. An overview of land consolidation in Europe. Nord. J. Surv. Real Estate Res. 2004, 1, 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Hiironen, J.; Riekkinen, K. Agricultural impacts and profitability of land consolidations. Land Use Policy 2016, 55, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Direktorat Jenderal Pengolahan Lahan. Pedoman Teknis Konsolidasi Pengelolaan Lahan Usahatani; Direktorat Jenderal Pengolahan Lahan: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sinuraya, J.F.; Agustin, N.K.; Pasaribu, S.M. Konsolidasi Lahan Pertanian Pangan: Kasus di Provinsi Jawa Tengah; Pasaribu, S.M., Saliem, H.P., Soeparno, H., Pasandaran, E., Kasryno, F., Eds.; Prosiding Konversi dan Fragmentasi Lahan; Litbang Pertanian: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, J. What is legal pluralism? J. Leg. Plur. Unoff. Law 1986, 18, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauterbach, C. South African Common and Customary Law on Intestate Succession: A Question of Harmonisation, Integration or Abolition. J. Comp. Law 2008, 3, 119. [Google Scholar]

- Nwauche, E.S. The Constitutional Challenge of the Integration and Interaction of Customary and the Received English Common Law in Nigeria and Ghana. Tulane Eur. Civ. Law Forum 2010, 25, 37. [Google Scholar]

- Holzinger, K.; Haer, R.; Bayer, A.; Behr, D.M.; Neupert-Wentz, C. The Constitutionalization of Indigenous Group Rights, Traditional Political Institutions, and Customary Law. Comp. Polit. Stud. 2019, 52, 1775–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutaqin, Z.Z. Indonesian Customary Law and European Colonialism: A Comparative Analysis on Adat Law. J. East Asia Int. Law 2011, 4, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, D. Environmental sustainability and legal plurality in irrigation: The Balinese subak. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2014, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Flick, U. Triangulation in data collection. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Collection; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2018; pp. 527–544. [Google Scholar]

- Flick, U. Triangulation in qualitative research. Companion Qual. Res. 2004, 3, 178–183. [Google Scholar]

- Kvale, S. Doing Interviews; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Situmorang, B.; Alih Fungsi Lahan Sawah Capai 150 Ribu Hektare. Republika Online. Available online: https://republika.co.id/share/p6wwdh384 (accessed on 10 May 2019).

- Daws, G.; Fujita, M. Archipelago: The islands of Indonesia: From the Nineteenth-Century Discoveries of Alfred Russel Wallace to the Fate of Forests and Reefs in the Twenty-First Century; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Badan Pusat Statistik Luas Lahan Sawah Menurut Provinsi (ha), 2003–2015. 2020. Available online: https://www.bps.go.id/linkTableDinamis/view/id/895 (accessed on 23 July 2020).

- Ntihinyurwa, P.D.; de Vries, W.T.; Chigbu, U.E.; Dukwiyimpuhwe, P.A. The positive impacts of farm land fragmentation in Rwanda. Land Use Policy 2019, 81, 565–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janti, G.I.; Martono, E. Perlindungan Lahan Pertanian Pangan Berkelanjutan Guna Memperkokoh Ketahanan Pangan Wilayah (Studi di Kabupaten Bantul, Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta). J. Ketahanan Nas. 2016, 22, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Nugraha, A.; Hestiawan, M.S.; Supyandi, D. Refleksi paradigma kedaulatan pangan di indonesia: Studi kasus gerakan pangan lokal di flores timur. Agricore J. Agribisnis Dan Sos. Ekon. Pertan. Unpad 2016, 1. Available online: http://jurnal.unpad.ac.id/agricore/article/view/22717 (accessed on 12 January 2021). [CrossRef]

- Statistik, B.P. “Provinsi Jawa Barat Dalam Angka 2021,” Badan Pusat Statistik Provinsi Jawa Barat, Bandung, Statistics. Available online: https://jabar.bps.go.id/publication/2021/02/26/4d3f7ec6c519dda0b9785d45/provinsi-jawa-barat-dalam-angka-2021.html (accessed on 27 June 2022).

- Riggs, R.A.; Sayer, J.; Margules, C.; Boedhihartono, A.K.; Langston, J.D.; Sutanto, H. Forest tenure and conflict in Indonesia: Contested rights in Rempek Village, Lombok. Land Use Policy 2016, 57, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, L.; Moniaga, S. The Space Between: Land Claims and the Law in Indonesia. Asian J. Soc. Sci. 2010, 38, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Demetriou, D. Land Fragmentation. In The Development of an Integrated Planning and Decision Support System (IPDSS) for Land Consolidation; Demetriou, D., Ed.; Springer Theses; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 11–37. ISBN 978-3-319-02347-2. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, S.; Zhu, F.; Chen, F.; Yu, M.; Zhang, S.; Yang, Y. Assessing the Impacts of Land Consolidation on Agricultural Technical Efficiency of Producers: A Survey from Jiangsu Province, China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugraha, A. An Ethnography Study of Farming Style in Gianyar, Bali, Indonesia; Wageningen University: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- MacRae, G.S.; Arthawiguna, I.W.A. Sustainable Agricultural Development in Bali: Is the Subak an Obstacle, an Agent or Subject? Hum. Ecol. 2011, 39, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacRae, G. Rice farming in bali: Organic Production and Marketing Challenges. Crit. Asian Stud. 2011, 43, 69–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiawan, I.; Kurnia, P.N. Existency, Role and Fading Local Wisdom of Tidal Farmer Community in Ciamis Regency. Mimb. J. Sos. Dan Pembang. 2021, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusters, K.; de Foresta, H.; Ekadinata, A.; van Noordwijk, M. Towards Solutions for State vs. Local Community Conflicts Over Forestland: The Impact of Formal Recognition of User Rights in Krui, Sumatra, Indonesia. Hum. Ecol. 2007, 35, 427–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, A.; Warren, C. Land for the People: The State and Agrarian Conflict in Indonesia; Ohio University Press: Athens, OH, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Susan, N.; Wahab, O.H. The Causes of Protracted Land Conflict in Indonesia’s Democracy: The Case of Land Conflict in Register 45, Mesuji Lampung Province, Indonesia. Int. J. Sustain. Future Hum. Secur. 2014, 2, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, R.E. de Multi-functional lands facing oil palm monocultures: A case study of a land conflict in West Kalimantan, Indonesia. ASEAS-Austrian J. South-East Asian Stud. 2016, 9, 11–32. [Google Scholar]

- Nugraha, A.; Heryanto, M.A.; Wulandari, E.; Pardian, P. Heading towards sustainable cacao agribusiness system (a case study in North Luwu, South Sulawesi, Indonesia). IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 306, 012035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruttan, V.W.; Hayami, Y. Toward a theory of induced institutional innovation. J. Dev. Stud. 1984, 20, 203–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 2015 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tasikmalaya | 140,335 | 87,205 | 83,365 | 72,941 | 82,935 |

| Cianjur | 244,805 | 236,054 | 117,909 | 113,856 | 113,539 |

| Sumedang | 60,427 | 54,300 | 56,439 | 55,892 | 53,341 |

| Ciamis | 69,431 | 53,557 | 51,209 | 52,925 | 55,013 |

| Pangandaran | 35,276 | 36,246 | 29,859 | 29,313 | 27,730 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kurnia, G.; Setiawan, I.; Tridakusumah, A.C.; Jaelani, G.; Heryanto, M.A.; Nugraha, A. Local Wisdom for Ensuring Agriculture Sustainability: A Case from Indonesia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8823. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148823

Kurnia G, Setiawan I, Tridakusumah AC, Jaelani G, Heryanto MA, Nugraha A. Local Wisdom for Ensuring Agriculture Sustainability: A Case from Indonesia. Sustainability. 2022; 14(14):8823. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148823

Chicago/Turabian StyleKurnia, Ganjar, Iwan Setiawan, Ahmad C. Tridakusumah, Gani Jaelani, Mahra A. Heryanto, and Adi Nugraha. 2022. "Local Wisdom for Ensuring Agriculture Sustainability: A Case from Indonesia" Sustainability 14, no. 14: 8823. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148823

APA StyleKurnia, G., Setiawan, I., Tridakusumah, A. C., Jaelani, G., Heryanto, M. A., & Nugraha, A. (2022). Local Wisdom for Ensuring Agriculture Sustainability: A Case from Indonesia. Sustainability, 14(14), 8823. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148823