The CAnadian Network for Psychedelic-Assisted Cancer Therapy (CAN-PACT): A Multi-Phase Program Overview

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Psychosocial Experience of Advanced Cancer

1.2. Psychedelic Renaissance and Regulation

1.3. Regulation

1.4. Psychedelic-Assisted Therapy for People with Advanced Cancer

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Aim

2.2. Objectives

- Build Capacity: Develop a national PAT research and practice network in cancer care.

- Research Priorities: Determine key PAT research priorities for people with advanced cancer through stakeholder engagement.

- Training Programs: Develop and implement PAT training and educational programs/materials for oncology healthcare providers, researchers, patient partners, and policymakers.

- Pilot Data Collection: Collect pilot and feasibility data to inform design of the larger trial.

- Clinical Trial: Conduct a multisite RCT of PAT in people with advanced cancer, supported by the Canadian Cancer Trials Group (CCTG).

- Policy Influence: Inform and influence Canadian healthcare policy to support PAT integration into cancer care.

2.3. Procedures

2.3.1. Objective 1: Build the CAN-PACT National Network

- Environmental Scan: Conduct a thorough scan of existing research and clinical programs across Canada related to PAT. This systematic assessment will adopt a pan-Canadian scope with targeted regional focus on key regions (British Columbia, Alberta, Ontario, Quebec and the Maritimes) to capture both national trends and regional variations in PAT implementation. The scan will systematically catalog program names, institutional affiliations, focus areas (research versus clinical), funding sources, and ongoing trials or initiatives, while documenting key outputs including publications, clinical trials, treatment protocols, and training materials. By limiting inclusion to credible, active participants in psychedelic research or clinical practices related to cancer, this environmental scan will identify critical gaps in service delivery, opportunities for strategic collaboration, and policy implications that could accelerate PAT integration into mainstream oncology care, where appropriate. While information will be collected on private fee-for-service programs, the emphasis for network membership will be on people working in publicly funded institutions (e.g., hospitals, universities, etc.).

- Network Engagement: Identify and create a directory of potential network members from interested groups including researchers, clinicians, patient advocacy groups, policymakers, and healthcare administrators. Advanced mapping tools (including Miro and Lucid chart) will be employed to visualize network connections and collaborative relationships, enabling strategic identification of influential nodes and potential partnership opportunities within the emerging Canadian PAT ecosystem.

- Network Development: Expand CAN-PACT membership and create collaborative working groups to focus on research, education, clinical care, and policy initiatives. These working groups will be structured around the gaps and opportunities identified through the environmental scan, ensuring an evidence-informed network architecture that maximizes collaborative potential while addressing identified system-level barriers.

- Annual Network Meetings: Hold regular virtual meetings and one large in-person annual meeting to promote collaboration and align goals, facilitating knowledge exchange and coordinated action across the distributed network while maintaining momentum toward shared objectives.

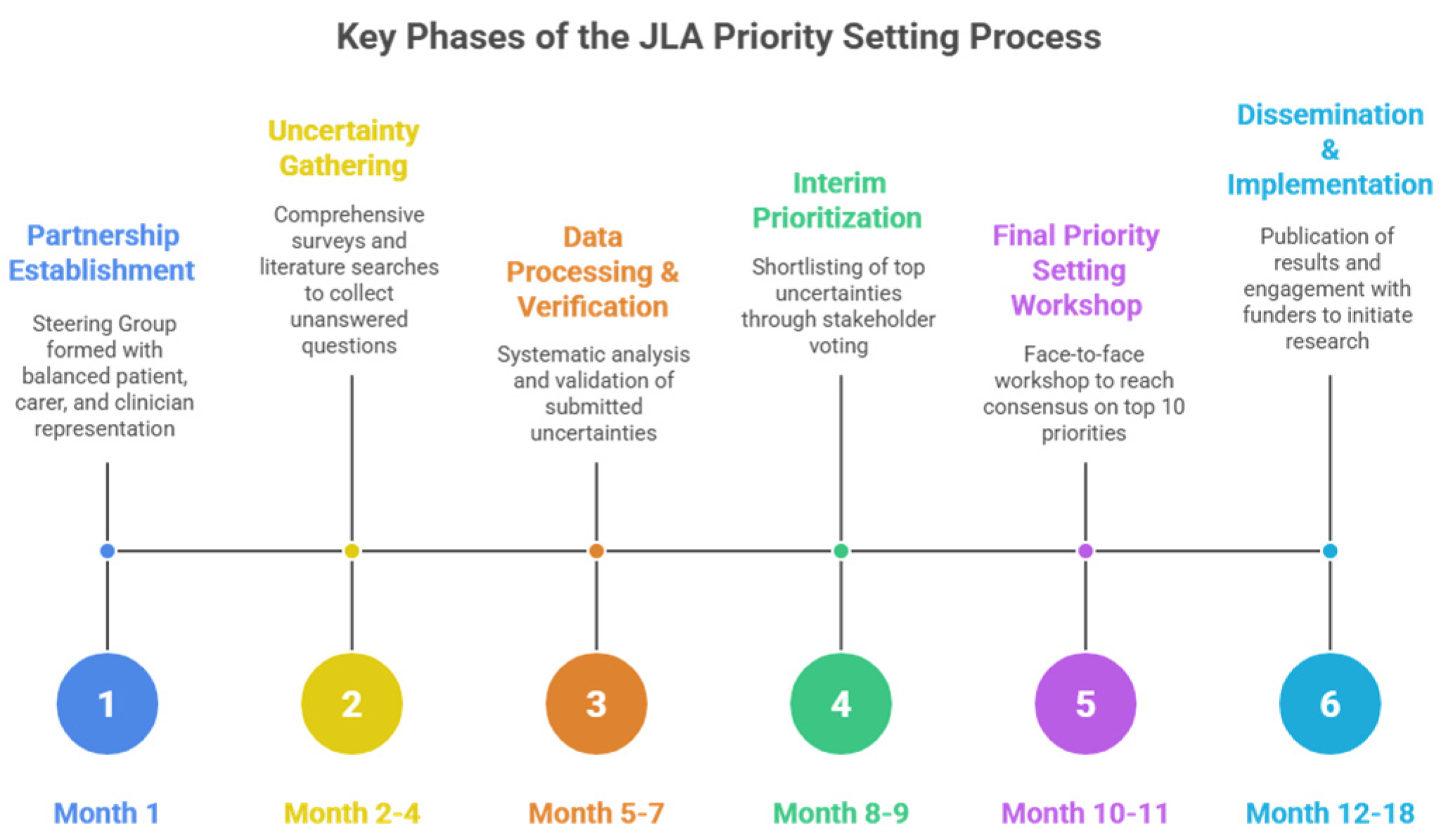

2.3.2. Objective 2: Determine PAT in Cancer Care Research Priorities Through Stakeholder Engagement

- Partnership Establishment: Formation of a Steering Group comprising balanced representation of patients, carers, and clinicians, supported by a JLA Adviser who provides independent facilitation throughout the process.

- Uncertainty Gathering: Collection of unanswered questions through comprehensive surveys targeting patients, carers, and clinicians, supplemented by searches of existing literature for documented uncertainties in guidelines and systematic reviews.

- Data Processing and Verification: Systematic analysis of survey responses to categorize submissions, form indicative research questions, and verify these as true uncertainties by checking against the current evidence base including systematic reviews and clinical guidelines.

- Interim Prioritization: Reduction in the long list of verified uncertainties to a manageable shortlist (typically 25–30 questions) through stakeholder voting, ensuring equal weighting of patient/carer and clinician perspectives.

- Final Priority Setting Workshop: A facilitated face-to-face workshop using an adapted Nominal Group Technique where diverse groups of interested parties engage in structured small group discussions and ranking exercises to reach consensus on the top 10 research priorities.

- Dissemination and Implementation: Publication of results and active engagement with research funders and academic communities to translate priorities into funded research studies.

2.3.3. Objective 3: Develop and Deliver PAT Training and Educational Programs

- Training for Clinicians, Researchers, and Students: CAN-PACT will build on existing partnerships and resources, with input from our Education subcommittee, to create specialized curricula for PAT in cancer care [40] (e.g., Adapting the University of Ottawa Psychedelics programming), drawing from disparate internationally recognized training standards for PAT and guidance documents [20,41]. The curriculum for both clinical and research trainees will incorporate a comprehensive theoretical foundation spanning several core competency areas, including pharmacological and neurobiological fundamentals, current clinical approaches to demoralization and existential or spiritual distress, consciousness and altered state research, Indigenous healing perspectives, and intercultural considerations specific to Canadian healthcare contexts. In parallel, research trainees (including graduate students and postdoctoral fellows) will receive structured education in the design, conduct, and analysis of psychedelic-assisted trials in oncology. This will include training in protocol development, selection and validation of psychosocial and clinical outcome measures, trial methodology for complex interventions, data management and statistical analysis plans, and integration of mechanistic (e.g., biomarker, digital health) sub-studies within pragmatic trial designs. Trainees will also gain experience in patient-oriented research methods, including stakeholder engagement, priority setting, and co-design of study procedures with people with lived experience, as well as knowledge translation strategies tailored to clinicians, patients, and policymakers.

- Clinical trainees in cancer care designated to deliver the intervention will also receive structured, standardized training in PAT delivery. A formal Mindfulness-Based PAT (MB-PAT) training curriculum is currently in development and will incorporate internationally recognized standards for psychedelic-assisted therapy training combined with elements of mindfulness-based cancer recovery [42] informed by the writings of Shapiro and Carlson [43]. This comprehensive manual will specify the following: (1) detailed protocols for group preparation including specific mindfulness-based training, psychoeducation on PAT mechanisms and treatment expectations, and developing the therapeutic alliance; (2) exact dosing procedure and session structure; (3) detailed integration protocols spanning post-session debriefing, mindfulness techniques, meaning-making, and clinical follow-up; and (4) competency benchmarks for therapist certification. Training will be delivered through multiple modalities including didactic instruction, direct observation of experienced practitioners, supervised role-play, and (where appropriate and permitted), closely supervised experiential components, with formal competency assessments and ongoing supervision to support fidelity. This approach emphasizes experiential training opportunities and comprehensive skill development spanning research design, clinical trial methodology, patient engagement, and knowledge translation. Researchers new to this area and research trainees (graduate students and postdoctoral fellows) will take part in similar core training components to clinicians. Training methods and modalities will include, but not be limited to, the following:

- Case Study Discussions: Regular interdisciplinary case study discussions examining the integration of PAT into Canadian psychosocial oncology and palliative care settings, incorporating structured colloquium methodologies that facilitate peer supervision and collaborative learning among multidisciplinary teams.

- Shadowing Opportunities: Structured observation of clinical trials, patient interactions, and experienced practitioners in palliative care, psychosocial oncology, and community partnerships, with systematic documentation and reflection processes to enhance therapeutic skill development through direct observation and post-session analysis.

- Ethics and Regulatory Training: Comprehensive training on Health Canada regulatory compliance, informed consent processes, and ethical considerations for vulnerable populations in psychedelic therapy contexts, incorporating specialized modules on boundary maintenance, crisis management, and cultural sensitivity within the Canadian healthcare framework.

- Skill Development: Clinical competencies, patient communication, regulatory compliance, mentorship capabilities, patient engagement, hands-on experience, and evidence-to-practice translation—all delivered through individualized learning pathways enhanced by peer supervision groups and ongoing professional development requirements.

- Patient and Family Education: Recognizing the critical importance of informed participation and community acceptance, we will develop culturally sensitive, accessible educational materials that address the unique informational needs of patients, families, and advocacy groups. These resources will provide evidence-based information on PAT’s therapeutic mechanisms, potential benefits for existential distress and demoralization syndrome, comprehensive safety profiles, and realistic outcome expectations. Educational materials will be co-developed with patient partners to ensure relevance and accessibility, incorporating diverse perspectives [44] and addressing concerns specific to cancer populations. We will utilize multiple dissemination formats including, but not limited to, infographics, video testimonials and informational FAQs, webinars, and interactive decision support tools, with materials available in multiple languages (beginning with French and English) to enhance equity and inclusion.

- Policymaker Education: To facilitate evidence-informed policy development and healthcare integration, we will engage policymakers to better understand their context, needs, and preferences and create targeted educational programs for policymakers, healthcare administrators, and regulatory bodies, with input from our policy subcommittee. These initiatives will emphasize the growing evidence base for PAT efficacy, as well as limitations, necessary safety protocols and risk mitigation strategies, economic considerations including cost-effectiveness analyses, and implementation frameworks for integration into publicly funded healthcare systems. Educational offerings will include policy briefs synthesizing current research, stakeholder roundtables bringing together researchers and decision-makers, and customized presentations addressing jurisdiction-specific regulatory and implementation challenges.

2.3.4. Objective 4: Pilot Data Collection on Key Outcomes

2.3.5. Objective 5: Conduct a Multisite RCT of PAT for People Living with Cancer

2.3.6. Objective 6: Influence Canadian Healthcare Policy on PAT

2.4. Patient and Public Involvement

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CAN-PACT | CAnadian Network for Psychedelic-Assisted Cancer Therapy |

| CCTG | Canadian Cancer Trials Group |

| CDSA | Controlled Drugs and Substances Act |

| CIHR | Canadian Institutes of Health Research |

| CTA | Clinical Trials Application |

| DS | Demoralization Syndrome |

| DMT | N,N-Dimethyltryptamine |

| EDI | Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion |

| IAA | Intention, Attention, Attitude (mindfulness model) |

| JLA | James Lind Alliance |

| LSD | Lysergic acid diethylamide |

| MAID | Medical Assistance in Dying |

| MB-PAT | Mindfulness-Based PAT |

| MDMA | 3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine |

| NYU | New York University |

| PAT | Psychedelic-Assisted Therapy |

| PSP | Priority Setting Partnership |

| PTSD | Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder |

| QoL | Quality of Life |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| SAP | Special Access Program |

References

- Canadian Cancer Society. Cancer Statistics at a Glance. Available online: https://cancer.ca/en/research/cancer-statistics/cancer-statistics-at-a-glance (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Essue, B.M.; Iragorri, N.; Fitzgerald, N.; de Oliveira, C. The psychosocial cost burden of cancer: A systematic literature review. Psychooncology 2020, 29, 1746–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, R.; Breitbart, W. Mental health care in oncology. Contemporary perspective on the psychosocial burden of cancer and evidence-based interventions. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2020, 29, e86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ann-Yi, S.; Bruera, E. Psychological Aspects of Care in Cancer Patients in the Last Weeks/Days of Life. Cancer Res. Treat. 2022, 54, 651–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fava, M.; Sorg, E.; Jacobs, J.M.; Leadbetter, R.; Guidi, J. Distinguishing and treating demoralization syndrome in cancer: A review. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2023, 85, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kissane, D.W.; Wein, S.; Love, A.; Lee, X.Q.; Kee, P.L.; Clarke, D.M. The Demoralization Scale: A report of its development and preliminary validation. J. Palliat. Care 2004, 20, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S.; Kissane, D.W.; Brooker, J.; Burney, S. A systematic review of the demoralization syndrome in individuals with progressive disease and cancer: A decade of research. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2015, 49, 595–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, H.; Ji, Q.; Wu, Q.; Wei, J.; Zhu, P. Prevalence, Associated Factors and Adverse Outcomes of Demoralization in Cancer Patients: A Decade of Systematic Review. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care 2023, 40, 1216–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Best, M.; Leget, C.; Goodhead, A.; Paal, P. An EAPC white paper on multi-disciplinary education for spiritual care in palliative care. BMC Palliat. Care 2020, 19, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, R.R.; Johnson, M.W.; Carducci, M.A.; Umbricht, A.; Richards, W.A.; Richards, B.D.; Cosimano, M.P.; Klinedinst, M.A. Psilocybin produces substantial and sustained decreases in depression and anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancer: A randomized double-blind trial. J. Psychopharmacol. 2016, 30, 1181–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, M.; Meged-Book, T.; Mashiach, T.; Bar-Sela, G. Distinguishing Between Spiritual Distress, General Distress, Spiritual Well-Being, and Spiritual Pain Among Cancer Patients During Oncology Treatment. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2017, 54, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.W.; Hendricks, P.S.; Barrett, F.S.; Griffiths, R.R. Classic psychedelics: An integrative review of epidemiology, therapeutics, mystical experience, and brain network function. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 197, 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doblin, R.E.; Merete, C.; Lisa, J.; Burge, B. The Past and Future of Psychedelic Science: An Introduction to This Issue. J. Psychoact. Drugs 2019, 51, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nichols, D.E. Psychedelics. Pharmacol. Rev. 2016, 68, 264–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nichols, D.E. Psilocybin: From ancient magic to modern medicine. J. Antibiot. 2020, 73, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Köck, P.; Froelich, K.; Walter, M.; Lang, U.; Dürsteler, K.M. A systematic literature review of clinical trials and therapeutic applications of ibogaine. J. Subst. Abus. Treat. 2022, 138, 108717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelmendi, B.; Kaye, A.P.; Pittenger, C.; Kwan, A.C. Psychedelics. Curr. Biol. 2022, 32, R63–R67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carhart-Harris, R.L.; Goodwin, G.M. The Therapeutic Potential of Psychedelic Drugs: Past, Present, and Future. Neuropsychopharmacology 2017, 42, 2105–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S. Therapeutic use of classic psychedelics to treat cancer-related psychiatric distress. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2018, 30, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochester, J.; Vallely, A.; Grof, P.; Williams, M.T.; Chang, H.; Caldwell, K. Entheogens and psychedelics in Canada: Proposal for a new paradigm. Can. Psychol./Psychol. Can. 2022, 63, 413–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilecki, B.; Luoma, J.B.; Bathje, G.J.; Rhea, J.; Narloch, V.F. Ethical and legal issues in psychedelic harm reduction and integration therapy Background information on psychedelic therapy, harm reduction, and integration. Harm Reduct. J. 2020, 18, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, R.G.; Bouso, J.C.; Rocha, J.M.; Rossi, G.N.; Hallak, J.E. The Use of Classic Hallucinogens/Psychedelics in a Therapeutic Context: Healthcare Policy Opportunities and Challenges. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2021, 14, 901–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Canada. Requests Through the Special Access Program for Psychedelic-Assisted Psychotherapy. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/drug-products/announcements/requests-special-access-program-psychedelic-assisted-psychotherapy.html (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Kratina, S.; Lo, C.; Strike, C.; Schwartz, R.; Rush, B. Psychedelics to Relieve Psychological Suffering Associated with a Life-Threatening Diagnosis: Time for a Canadian Policy Discussion. Healthc. Policy 2023, 18, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S.; Bossis, A.; Guss, J.; Agin-Liebes, G.; Malone, T.; Cohen, B.; Mennenga, S.E.; Belser, A.; Kalliontzi, K.; Babb, J.; et al. Rapid and sustained symptom reduction following psilocybin treatment for anxiety and depression in patients with life-threatening cancer: A randomized controlled trial. J. Psychopharmacol. 2016, 30, 1165–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S.; Agin-Liebes, G.; Lo, S.; Zeifman, R.J.; Ghazal, L.; Benville, J.; Franco Corso, S.; Bjerre Real, C.; Guss, J.; Bossis, A.; et al. Acute and Sustained Reductions in Loss of Meaning and Suicidal Ideation Following Psilocybin-Assisted Psychotherapy for Psychiatric and Existential Distress in Life-Threatening Cancer. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2021, 4, 553–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.L.; Yang, F.C.; Yang, S.N.; Tseng, P.T.; Stubbs, B.; Yeh, T.C.; Hsu, C.W.; Li, D.J.; Liang, C.S. Psilocybin for End-of-Life Anxiety Symptoms: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychiatry Investig. 2021, 18, 958–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S.; Agrawal, M.; Griffiths, R.R.; Grob, C.; Berger, A.; Henningfield, J.E. Psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy to treat psychiatric and existential distress in life-threatening medical illnesses and palliative care. Neuropharmacology 2022, 216, 109174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, B.R.; Garland, E.L.; Byrne, K.; Durns, T.; Hendrick, J.; Beck, A.; Thielking, P. HOPE: A Pilot Study of Psilocybin Enhanced Group Psychotherapy in Patients with Cancer. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2023, 66, 258–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, M.; Emanuel, E.; Richards, B.; Richards, W.; Roddy, K.; Thambi, P. Assessment of Psilocybin Therapy for Patients with Cancer and Major Depression Disorder. JAMA Oncol. 2023, 9, 864–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehto, R.H.; Miller, M.; Sender, J. The Role of Psilocybin-Assisted Psychotherapy to Support Patients with Cancer: A Critical Scoping Review of the Research. J. Holist. Nurs. 2021, 40, 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuman, H.D.M.; Savard, C.; Mina, R.; Barkova, S.; Conradi, H.; Deleemans, J.M.; Carlson, L.E. Psychedelic-assisted therapies for psychosocial symptoms in cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aday, J.S.; Simonsson, O.; Schindler, E.A.D.; D’Souza, D.C. Addressing blinding in classic psychedelic studies with innovative active placebos. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2025, 28, pyaf023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittur, M.E.; Burgos, M.L.; Jones, B.D.M.; Blumberger, D.M.; Mulsant, B.H.; Rosenblat, J.D.; Husain, M.I. Mapping psilocybin therapy: A systematic review of therapeutic frameworks, adaptations, and standardization across contemporary clinical trials. J. Affect. Disord. 2025, 391, 119952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogg, C.; Michaels, T.I.; de la Salle, S.; Jahn, Z.W.; Williams, M.T. Ethnoracial health disparities and the ethnopsychopharmacology of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapies. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2021, 29, 539–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, M.E.; Garcia-Romeu, A. Ethnoracial inclusion in clinical trials of psychedelics: A systematic review. eClinicalMedicine 2024, 74, 102711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J.R.; Michaels, T.I.; Sevelius, J.; Williams, M.T. The psychedelic renaissance and the limitations of a White-dominant medical framework: A call for indigenous and ethnic minority inclusion. J. Psychedelic Stud. 2020, 4, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ching, T.H.W.; Kelmendi, B. A primer for culturally attuned psychedelic clinical trials. J. Psychedelic Stud. 2025, 9, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James Lind Alliance. The James Lind Alliance. Available online: https://www.jla.nihr.ac.uk/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- University of Ottawa. Certificate in Psychedelic-Assisted Therapies. Available online: https://psychedelicstudies.ca/certificate.php (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Phelps, J. Developing Guidelines and Competencies for the Training of Psychedelic Therapists. J. Humanist. Psychol. 2017, 57, 450–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, L.; Speca, M.; Segal, Z. Mindfulness-Based Cancer Recovery: A Step-by-Step MBSR Approach to Help You Cope with Treatment and Reclaim Your Life; New Harbinger Publications: Oakland, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, S.L.; Carlson, L.E.; Sawyer, B.A. The Art & Science of Mindfulness: Integrating Mindfulness into the Helping Professions, 3rd ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, R.; Ching, T.H.W.; Bartlett, A.C.; La Torre, J.T.; Williams, M.T. Healing Words: Effects of Psychoeducation on Likelihood to Seek and Refer Psychedelic-Assisted Psychotherapy Among BIPOC Individuals. J. Psychoact. Drugs 2024, 56, 603–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, L. Optimization of Behavioral, Biobehavioral, and Biomedical Interventions: The Multiphase Optimization Strategy (MOST); Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, L.E. Psychosocial and Integrative Oncology: Interventions Across the Disease Trajectory. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2023, 74, 457–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, B.X.Z.; Ng, S.W.; Lim, Y.S.E.; Goh, H.B.; Kumari, Y. The immunomodulatory effects of classical psychedelics: A systematic review of preclinical studies. Progress Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2025, 136, 111139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kargbo, R.B. Microbiome: The Next Frontier in Psychedelic Renaissance. J. Xenobiot. 2023, 13, 386–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caspani, G.; Ruffell, G.D.S.; Tsang, W.; Netzband, N.; Rohani-Shukla, C.; Swann, R.J.; Jefferies, A.W. Mind over matter: The microbial mindscapes of psychedelics and the gut-brain axis. Pharmacol. Res. 2024, 207, 107338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canadian Cancer Trials Group. Priorities in Cancer Research. Available online: https://www.ctg.queensu.ca/public/priorities-cancer-research (accessed on 10 October 2025).

| Compound | Common Name/Source | Mechanism of Action | Reported Psychological Effects in Humans | Common Adverse Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psilocybin | “Magic mushrooms” (Psilocybe genus) | Psilocybin is dephosphorylated to psilocin, which activates 5-HT2A receptors on glutamatergic pyramidal neurons in the neocortex, thalamus, and other key brain regions, causing widespread desynchronization of brain networks including the default mode network and anterior hippocampus. | Profound mystical experiences, altered perception of time and space, enhanced introspection and emotional processing, ego dissolution, visual hallucinations (eyes closed), enhanced connectedness to nature and others, spiritual insights, lasting improvements in well-being and life satisfaction. Effects typically last 4–8 h. | Transient anxiety, nausea, headache, elevated blood pressure, and post-session headache. Rarely any persistent long-term medical or psychiatric sequalae. |

| Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD-25) | “Acid” Semi-synthetic psychedelic | LSD potently activates 5-HT2A, 5-HT2B, and 5-HT2C serotonin receptors, as well as dopamine D2/D3/D4 and α-adrenergic receptors; its slow dissociation from 5-HT2A receptors prolongs signaling duration and downstream effects. | Intense visual and auditory hallucinations, altered perception of time, synesthesia (blending of senses), heightened creativity, profound introspective insights, ego dissolution, enhanced emotional sensitivity, lasting changes in personality openness, spiritual experiences. Effects typically last 8–12 h. | Can result in anxiety, perceptual changes, nausea, modest heart rate/blood pressure increases, and rarely, longer psychotic or delusional episodes in at-risk populations. |

| N,N-Dimethyltryptamine (DMT) | Ayahuasca brew component Psychotria Viridis leaves | DMT is a tryptamine that activates 5-HT2A, 5-HT1A, and dopamine D2/D3/D4 receptors; it is not orally bioavailable due to rapid MAO-A metabolism and induces dendritic proliferation in neurons. | Intense but short-duration mystical experiences, ego dissolution, profound spiritual insights, life-changing perspectives on death and meaning. Effects typically last 15–30 min (smoked DMT), peak effect 1–2 h lasting 6–8 h (ayahuasca tea by oral ingestion). | Can lead to rapid-onset anxiety, confusion, intense but short-lived visual effects, with nausea and raised vital signs especially in oral (ayahuasca) use. |

| 5-MeO-DMT | Found naturally in the Bufo alvarius toad | 5-MeO-DMT is a non-selective serotonin receptor agonist with highest affinity for 5-HT1A receptors and secondary activity at 5-HT1B, 5-HT1D, 5-HT6, 5-HT7, and 5-HT2C receptors. It readily crosses the blood–brain barrier and distributes widely throughout the brain, producing behavioral effects primarily through 5-HT1A receptor activation while disrupting medial prefrontal cortex oscillations and reducing visual cortex activity. | Users report transcendent experiences involving ego dissolution and non-dual awareness, with emotions ranging from love and awe to panic and terror. Notably, visual effects are often absent; instead, users describe “content-free” states of emptiness or void. When smoked, effects peak within 2–5 min, last 15–20 min, and resolve by 30 min; 90% report positive/transcendent experiences, with 57% meeting criteria for complete mystical experience. | Acute effects include fear, anxiety, paranoia, nausea, vomiting, trembling, and chest/abdominal pressure, with approximately 37% experiencing challenging psychological and somatic effects. Delayed effects (up to 1 week) include muscle tension, sleep difficulties, and flashbacks, while rare cases of psychosis and memory loss have been reported. |

| Mescaline | “Mescal” Peyote and San Pedro cacti | Mescaline activates 5-HT2A, 5-HT2B, and 5-HT2C serotonin receptors and dopamine D2/D3/D4 receptors while remaining inert at D1/D5 receptors. | Enhanced visual perception with vivid colors and patterns, deep introspection and emotional insights, connection to nature, enhanced empathy, minimal visual distortions compared to other psychedelics. Effects typically last 8–12 h. | Can lead to nausea, anxiety, perceptual alterations, and mild cardiovascular stimulation, with rare persistent psychiatric symptoms. |

| MDMA | “Ecstasy” (3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine) | MDMA acts primarily through serotonin reuptake inhibition rather than direct serotonin receptor activation, showing minimal 5-HT2A receptor engagement compared to classical psychedelics. | Increased empathy and emotional openness, enhanced social connection and bonding, reduced fear and defensiveness, heightened tactile sensitivity, mild visual enhancements, increased energy and euphoria, enhanced therapeutic communication and trauma processing. Effects typically last 3–6 h. | Can produce jaw clenching, dry mouth, mild hyperthermia, increased heart rate, transient anxiety or paranoia, serotonin syndrome in rare cases, and low mood after use. |

| Ketamine | “K” Dissociative anesthetic | Ketamine is a dissociative that engages glutamate-dependent homeostatic plasticity mechanisms and modulates limbic connectivity, producing network desynchronization patterns similar to classical psychedelics. | Dissociative effects creating a sense of detachment from body/environment, rapid antidepressant effects, altered perception of reality, out-of-body experiences, reduced rumination and negative thought patterns, pain relief, dream-like states. Effects typically last 1–2 h. | Induces dissociation, dizziness, increased blood pressure, and, at higher or repeated doses, can cause agitation, confusion, or urinary issues. Substantial addiction and abuse liability. |

| Ibogaine | Found in the root bark of Tabernanthe iboga (‘Iboga’) | Ibogaine acts on multiple targets—including NMDA, sigma-2, opioid, and serotonin systems, as well as nicotinic receptors—to reduce drug-seeking, but increases cardiotoxicity risk via hERG channel blockade and QT prolongation. | Ibogaine produces a multi-phase subjective experience beginning with an intense, dream-like state featuring vivid imagery and deep introspection, followed by a reflective, emotionally neutral period, and ending with a residual phase of heightened awareness and possible sleep disruption. Effects can last between 24 and 72 h. | Can cause nausea, tremors, ataxia, cardiac risks (QT prolongation and arrhythmias), rare mania or seizures, and in rare cases, has resulted in fatal outcomes. |

| Mindfulness | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Intensive | Minimal | ||

| Psilocybin | High dose | Combines masked high-dose psilocybin with intensive mindfulness-based preparation and integration, potentially maximizing therapeutic effects. | Explores the impact of masked high-dose psilocybin with minimal preparation, isolating the potential effect of psilocybin. |

| Low dose | Combines masked low-dose psilocybin with intensive mindfulness-based preparation and integration, isolating the effect of mindfulness. | Investigates baseline effects of masked low-dose psilocybin with minimal preparation, serving as a control/placebo comparator. | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Carlson, L.E.; Richardson, H.; Shore, R.; Albertyn, C.P.; Balneaves, L.G.; Bates, A.; Burnell, M.; Chochinov, H.M.; Clements, D.; Deleemans, J.; et al. The CAnadian Network for Psychedelic-Assisted Cancer Therapy (CAN-PACT): A Multi-Phase Program Overview. Curr. Oncol. 2026, 33, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol33010007

Carlson LE, Richardson H, Shore R, Albertyn CP, Balneaves LG, Bates A, Burnell M, Chochinov HM, Clements D, Deleemans J, et al. The CAnadian Network for Psychedelic-Assisted Cancer Therapy (CAN-PACT): A Multi-Phase Program Overview. Current Oncology. 2026; 33(1):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol33010007

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarlson, Linda E., Harriet Richardson, Ron Shore, Christopher P. Albertyn, Lynda G. Balneaves, Alan Bates, Margot Burnell, Harvey Max Chochinov, David Clements, Julie Deleemans, and et al. 2026. "The CAnadian Network for Psychedelic-Assisted Cancer Therapy (CAN-PACT): A Multi-Phase Program Overview" Current Oncology 33, no. 1: 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol33010007

APA StyleCarlson, L. E., Richardson, H., Shore, R., Albertyn, C. P., Balneaves, L. G., Bates, A., Burnell, M., Chochinov, H. M., Clements, D., Deleemans, J., Horlock, H., Mathews, J., McKenzie, M., Savard, C., Soares, C. N., Tu, W., & Williams, M. (2026). The CAnadian Network for Psychedelic-Assisted Cancer Therapy (CAN-PACT): A Multi-Phase Program Overview. Current Oncology, 33(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol33010007